McConnell Campbell R., Brue Stanley L., Barbiero Thomas P. Microeconomics. Ninth Edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

tomato farmer, the market period may be a full growing season; for producers of

goods that can be inexpensively stored, there may be no market period at all.

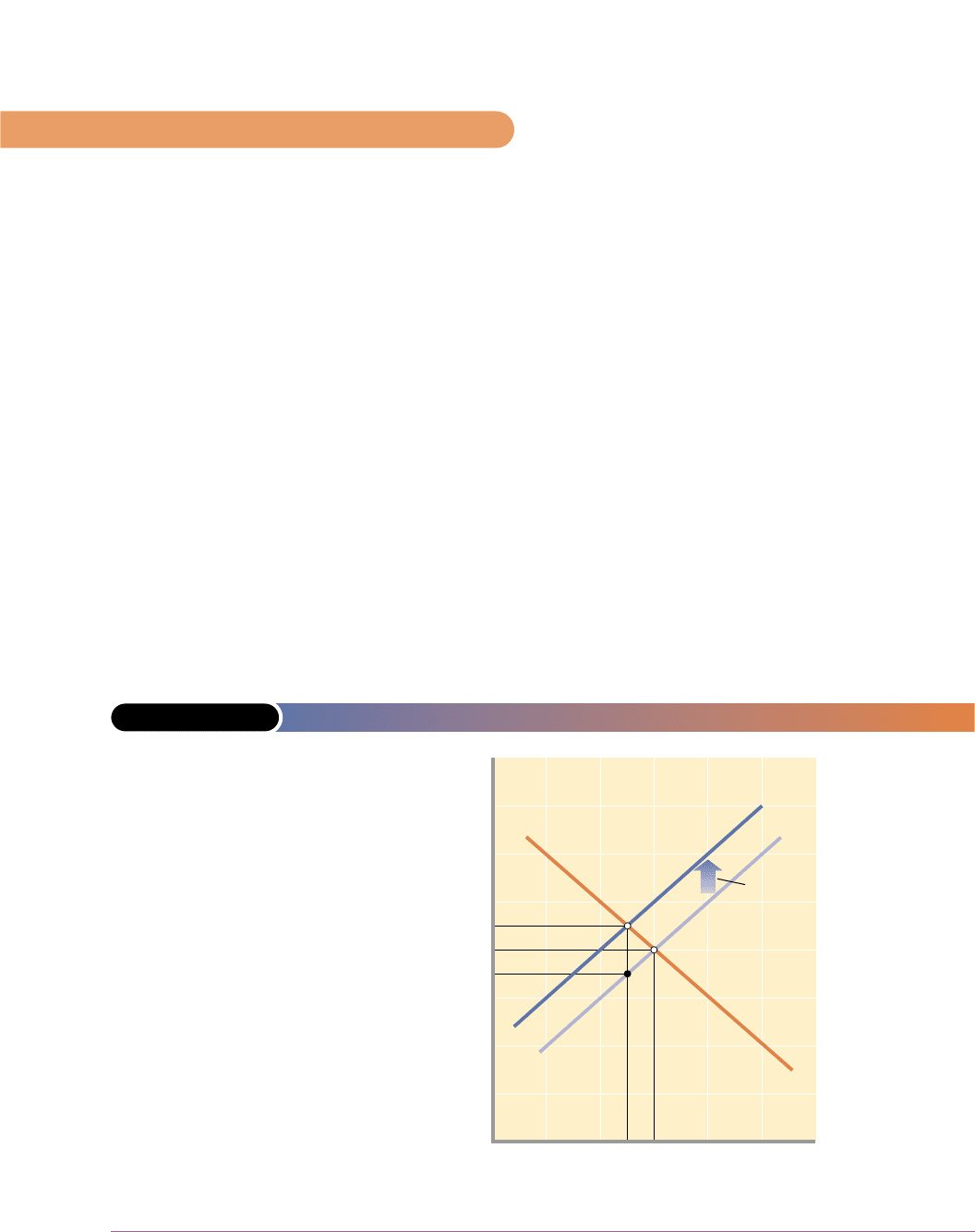

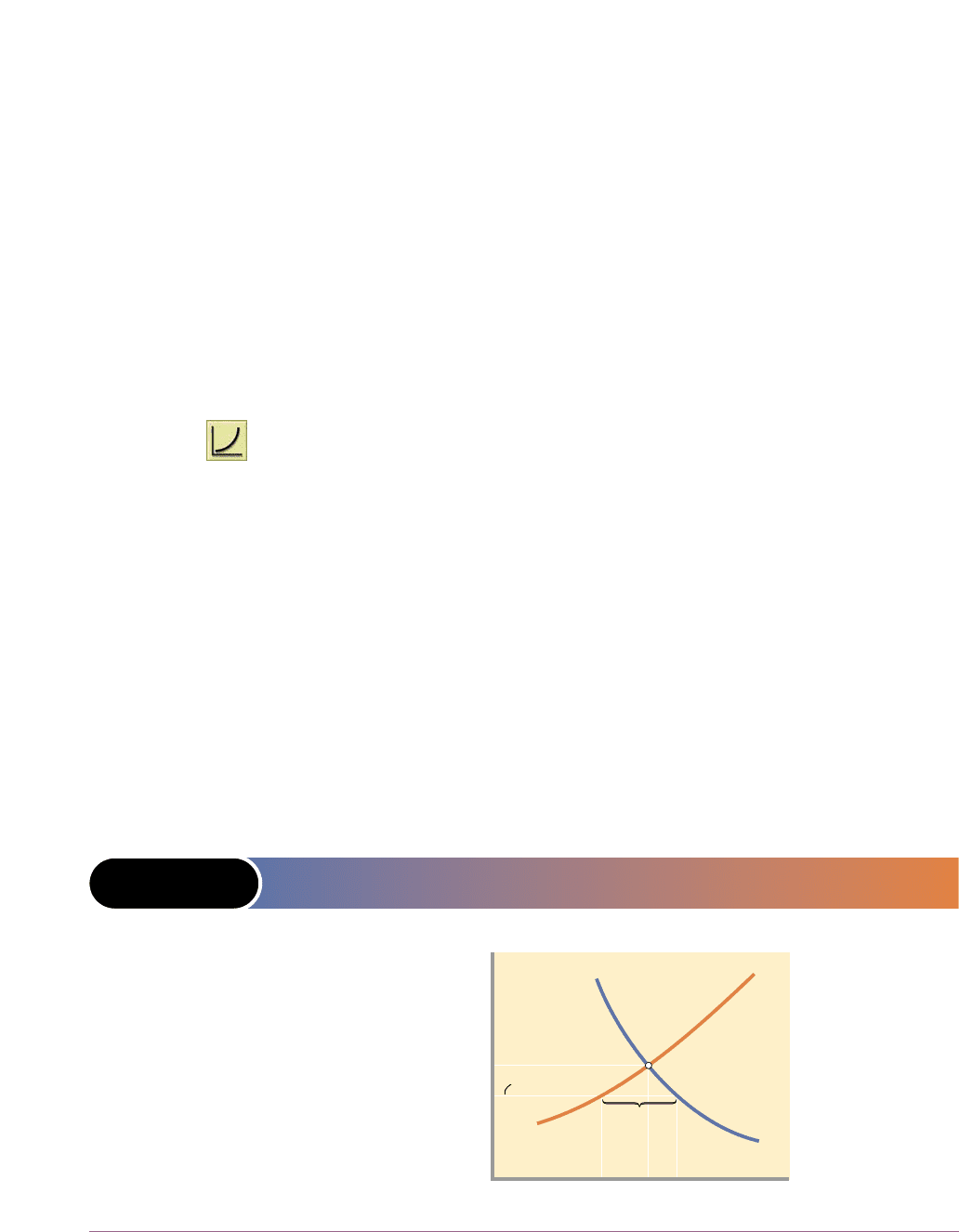

Price Elasticity of Supply: The Short Run

In the short run, the plant capacity of individual producers and of the entire industry

is fixed. Even so, firms do have time to use their fixed plants more or less intensively.

In the short run, our farmer’s plant (land and farm machinery) is fixed, but time is

available in the short run to cultivate tomatoes more intensively by applying more

labour and more fertilizer and pesticides to the crop. The result is a somewhat greater

output in response to a presumed increase in demand; this greater output is reflected

in a more elastic supply of tomatoes, as shown by figure S

s

in Figure 6-3(b). Note now

that the increase in demand from D

1

to D

2

is met by an increase in quantity (from Q

0

to Q

s

), so there is a smaller price adjustment (from P

0

to P

s

) than in the market period.

The equilibrium price is, therefore, lower in the short run than in the market period.

Price Elasticity of Supply: The Long Run

The long run is a period long enough for firms to adjust their plant sizes and for new

firms to enter (or existing firms to leave) the industry. In the tomato industry, for

example, our farmer has time to acquire additional land and buy more machinery

and equipment. Furthermore, other farmers may, over time, be attracted to tomato

farming by the increased demand and higher price. Such adjustments create a larger

supply response, as represented by the more elastic supply curve S

L

in Figure 6-3(c).

The outcome is a smaller price rise (P

0

to P

1

) and a larger output increase (Q

0

to Q

1

)

in response to the increase in demand from D

1

to D

2

. (Key Question 10)

There is no total-revenue test for elasticity of supply. Supply shows a positive or

direct relationship between price and amount supplied; the supply curve is upslop-

ing. Regardless of the degree of elasticity or inelasticity, price and total revenue

always move together.

Price elasticities measure the responsiveness of the quantity of a product demanded

or supplied when its price changes. The consumption of a good also is affected by

a change in the price of a related product or by a change in income.

Cross Elasticity of Demand

The cross elasticity of demand measures how sensitive consumer purchases of one

product (say, X) are to a change in the price of some other product (say, Y). We cal-

culate the coefficient of cross elasticity of demand E

xy

just as we do the coefficient of

simple price elasticity, except that we relate the percentage change in the consump-

tion of X to the percentage change in the price of Y:

E

xy

=

This cross elasticity (or cross price elasticity) concept allows us to quantify

and more fully understand substitute and complementary goods, introduced in

Chapter 3.

percentage change in quantity demanded of product X

ᎏᎏᎏᎏᎏᎏᎏ

percentage change in price of product Y

140 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

short run A

period of time in

which producers

are able to change

the quantities of

some but not all of

the resources they

employ.

long run A

period of time long

enough to enable

producers of a

product to change

the quantities of all

the resources they

employ.

cross

elasticity

of demand

The ratio of the

percentage change

in quantity

demanded of one

good to the percent-

age change in the

price of some other

good; a positive

coefficient indicates

the two products are

substitute goods; a

negative coefficient

indicates they are

complementary

goods.

Cross Elasticity and Income

Elasticity of Demand

SUBSTITUTE GOODS

If cross elasticity of demand is positive, meaning that sales of X move in the same

direction as a change in the price of Y, then X and Y are substitute goods. An exam-

ple is Kodak film (X) and Fuji film (Y). An increase in the price of Kodak film causes

consumers to buy more Fuji film, resulting in a positive cross elasticity. The larger

the positive cross elasticity coefficient, the greater the substitutability between the

two products.

COMPLEMENTARY GOODS

When cross elasticity is negative, we know that X and Y move together; an increase

in the price of one decreases the demand for the other. They are complementary

goods. For example, an increase in the price of cameras will decrease the amount of

film purchased. The larger the negative cross elasticity coefficient, the greater is the

complementarity between the two goods.

INDEPENDENT GOODS

A zero or near-zero cross elasticity suggests that the two products being considered

are unrelated or independent goods. An example is walnuts and film; we would not

expect a change in the price of walnuts to have any effect on purchases of film, and

vice versa.

APPLICATIONS

The degree of substitutability of products, measured by the cross elasticity coeffi-

cient, is important to businesses and government. For example, suppose that Coca-

Cola is considering whether to lower the price of its Sprite brand. Not only will it

want to know something about the price elasticity of demand for Sprite (will the

price cut increase or decrease total revenue?), it will also be interested in knowing

whether the increased sale of Sprite will come at the expense of its Coke brand. How

sensitive are the sales of one of its products (Coke) to a change in the price of

another of its products (Sprite)? By how much will the increased sales of Sprite can-

nibalize the sales of Coke? A low cross elasticity would indicate that Coke and Sprite

are weak substitutes for each other and a lower price for Sprite would have little

effect on Coke sales.

Government also implicitly uses the idea of cross elasticity of demand in assess-

ing whether a proposed merger between two large firms will substantially reduce

competition and violate the antitrust laws. For example, the cross elasticity between

Coke and Pepsi is high, making them strong substitutes for each other. Conse-

quently, the government would likely block a merger between the two companies

because it would lessen competition. In contrast, the cross elasticity between film

and gasoline is low or zero. A merger between Kodak and Petro-Canada would have

a minimal effect on competition, so government would let that merger happen.

Income Elasticity of Demand

Income elasticity of demand measures the degree to which consumers respond to

a change in their income by buying more or less of a particular good. The coefficient

of income elasticity of demand, E

i

, is determined with the formula

E

i

=

percentage change in quantity demanded

ᎏᎏᎏᎏᎏ

percentage change in income

chapter six • supply and demand: elasticities and government-set prices 141

income

elasticity

of demand

The ratio of the

percentage change

in the quantity

demanded of a good

to a percentage

change in consumer

income; measures

the responsiveness

of consumer pur-

chases to income

changes.

NORMAL GOODS

For most goods, the income elasticity coefficient E

i

is positive, meaning that more of

them are demanded as incomes rise. Such goods are called normal or superior

goods, which we first described in Chapter 3. The value of E

i

varies greatly among

normal goods. For example, income elasticity of demand for automobiles is about

+3.00, while income elasticity for most farm products is only about +.20.

INFERIOR GOODS

A negative income elasticity coefficient designates an inferior good. Retread tires,

cabbage, long-distance bus tickets, used clothing, and muscatel wine are likely can-

didates. Consumers decrease their purchases of inferior goods as incomes rise.

INSIGHTS

Coefficients of income elasticity of demand provide insights into the economy.

For example, income elasticity helps to explain the expansion and contraction of

industries in Canada. On average, total income in the economy has grown by 2

to 3 percent annually. As income has expanded, industries producing products

for which demand is quite income elastic have expanded their outputs. Thus, auto-

mobiles (E

i

= +3), housing (E

i

= +1.5), books (E

i

= +1.4), and restaurant meals (E

i

=

+1.4) have all experienced strong growth of output. Meanwhile, industries pro-

ducing products for which income elasticity is low or negative have tended to

grow slowly or to decline. For example, agriculture (E

i

= +.20) has grown far more

slowly than has the economy’s total output. We do not eat twice as much when our

incomes double.

As another example, when recessions occur and people’s incomes decline, gro-

cery stores fare relatively better than stores selling electronic equipment. People do

not substantially cut back on their purchases of food when their incomes fall;

income elasticity of demand for food is relatively low. But they do substantially cut

back on their purchases of electronic equipment; income elasticity on such equip-

ment is relatively high. (Key Questions 12 and 13)

In Table 6-4 we provide a synopsis of the cross elasticity and income elasticity

concepts.

142 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

TABLE 6-4 CROSS AND INCOME ELASTICITIES OF DEMAND

Value of coefficient Description Type of good(s)

Cross elasticity:

Positive (E

wz

> 0) Quantity demanded of W changes in same direction Substitutes

as change in price of Z

Negative (E

xy

< 0) Quantity demanded of X changes in opposite direction Complements

from change in price of Y

Income elasticity:

Positive (E

i

> 0) Quantity demanded of the product changes in same Normal or

direction as change in income superior

Negative (E

i

< 0) Quantity demanded of the product changes in opposite Inferior

direction from change in income

Supply and demand analysis and the elasticity concept are applied repeatedly in the

remainder of this book. Let’s strengthen our understanding of these analytical tools

and their significance by examining elasticity and tax incidence.

Elasticity and Tax Incidence

In Figure 6-4, S and D represent the pretax market for a certain domestic wine from

the Niagara Peninsula. The no-tax equilibrium price and quantity are $4 per bottle

and 15 million bottles. If government levies a tax of $1 per bottle directly on the win-

ery for every bottle sold, who actually pays it?

DIVISION OF BURDEN

Since government places the tax on the sellers (suppliers), the tax can be viewed as

an addition to the marginal cost of the product. Now sellers must get $1 more for

each bottle to receive the same per-unit profit they were getting before the tax. While

sellers are willing to offer, for example, five million bottles of untaxed wine at $2 per

bottle, they must now receive $3 per bottle—$2 plus the $1 tax—to offer the same

five million bottles. The tax shifts the supply curve upward (leftward) as shown in

Figure 6-4, where S

t

is the after-tax supply curve.

The after-tax equilibrium price is $4.50 per bottle, whereas the before-tax price

was $4.00. So, in this case, half the $1 tax is paid by consumers as a higher price; the

other half must be paid by producers in a lower after-tax per-unit revenue. That is,

after paying the $1 tax per unit to the government, producers receive $3.50, or 50¢

chapter six • supply and demand: elasticities and government-set prices 143

FIGURE 6-4 THE INCIDENCE OF A TAX

Tax $1

S

t

S

D

$6

5

4

3

2

1

0

510152025

Q

P

Quantity

(millions of bottles per month)

Price (per bottle)

A tax of a specified

amount per unit

levied on producers,

here $1 per unit,

shifts the supply

curve upward by the

amount of the tax per

unit: the vertical dis-

tance between S and

S

t

. This shift results in

a higher price (here

$4.50) to the con-

sumer and a lower

after-tax price (here

$3.50) to the pro-

ducer. Thus,

consumers and pro-

ducers share the

burden of the tax in

some proportion

(here equally at $.50

per unit).

Elasticity and Taxes

less than the $4.00 before-tax price. In this instance, consumers and producers share

the burden of this tax equally; producers shift half the tax to consumers in a higher

price and bear the other half themselves.

Note also that the equilibrium quantity decreases as a result of the tax levy and

the higher price it imposes on consumers. In Figure 6-4, that decline in quantity is

from 15 million bottles per month to 12.5 million bottles per month.

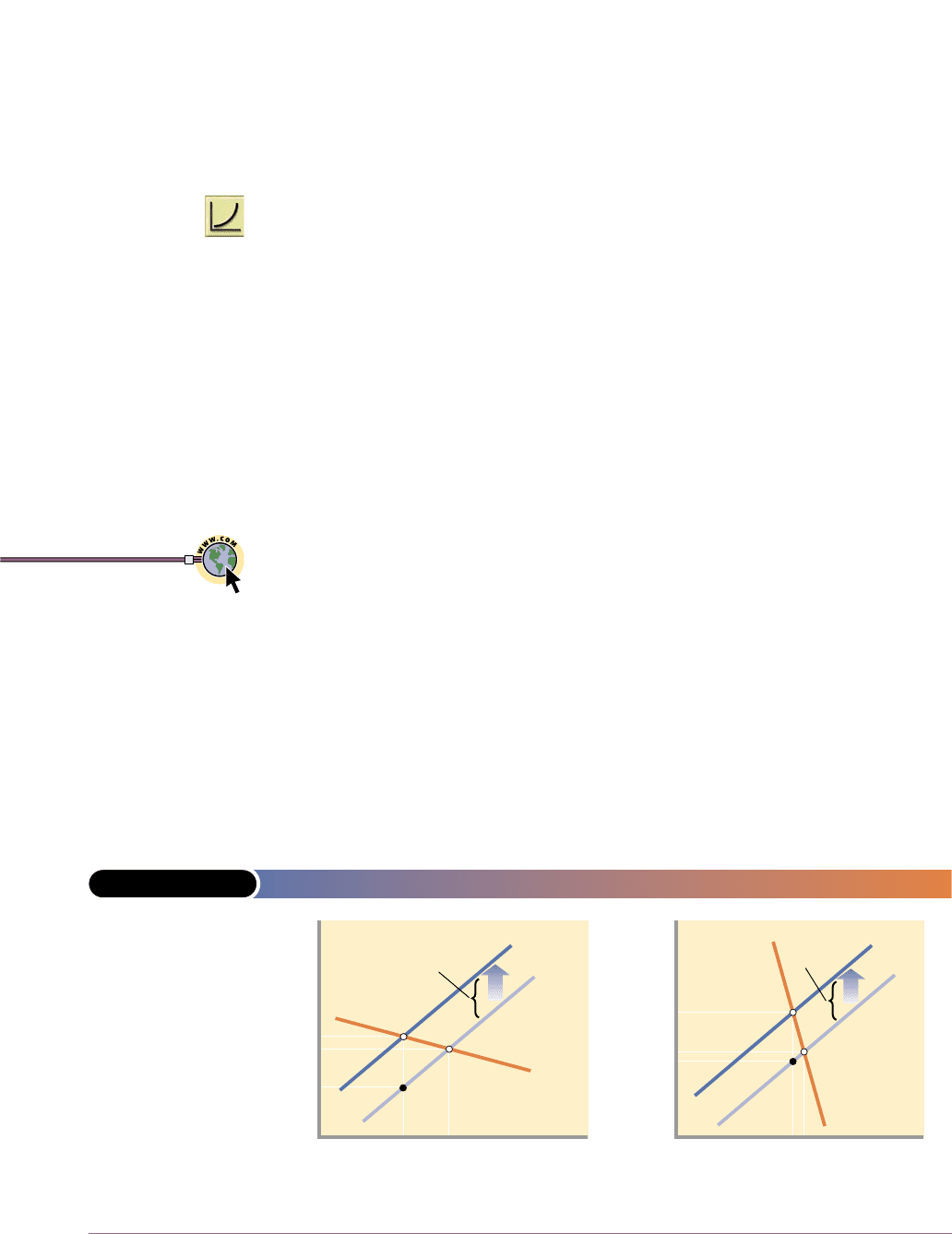

ELASTICITIES

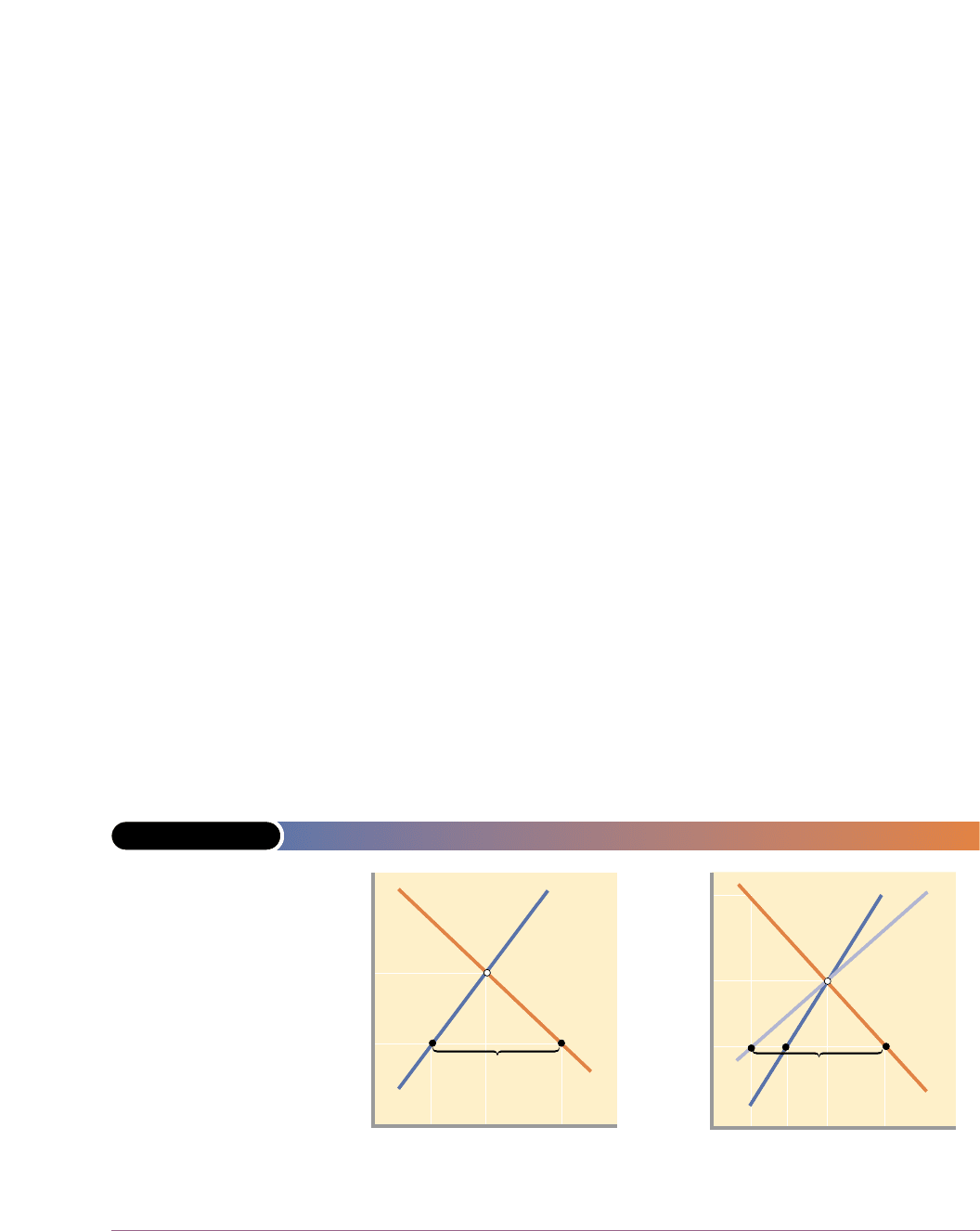

If the elasticities of demand and supply were different from those shown in Figure

6-4, the incidence of tax would also be different. Two generalizations are relevant.

First, with a specific supply, the more inelastic the demand for the product, the larger the

portion of the tax shifted to consumers. To verify this, sketch graphically the extreme

cases where demand is perfectly elastic or perfectly inelastic. In the first case, the

incidence of the tax is entirely on sellers; in the second, the tax is shifted entirely to

consumers.

Figure 6-5 contrasts the more usual cases where demand is either relatively elas-

tic or relatively inelastic in the relevant price range. With elastic demand, shown in

Figure 6-5(a), a small portion of the tax (P

e

– P

1

) is shifted to consumers and most of

the tax (P

1

– P

2

) is borne by the producers. With inelastic demand, shown in Figure

6-5(b), most of the tax (P

i

– P

1

) is shifted to consumers and only a small amount

(P

1

– P

b

) is paid by producers. In both graphs the per-unit tax is represented by the

vertical distance between S

t

and S.

Note also that the decline in equilibrium quantity (Q

1

– Q

2

) is smaller when

demand is more inelastic, which is the basis of our previous applications of the elas-

ticity concept: Revenue-seeking legislatures place heavy excise taxes on liquor, cig-

arettes, automobile tires, telephone service, and other products whose demands are

thought to be inelastic. Since demand for these products is relatively inelastic, the

tax does not reduce sales much, so the tax revenue stays high.

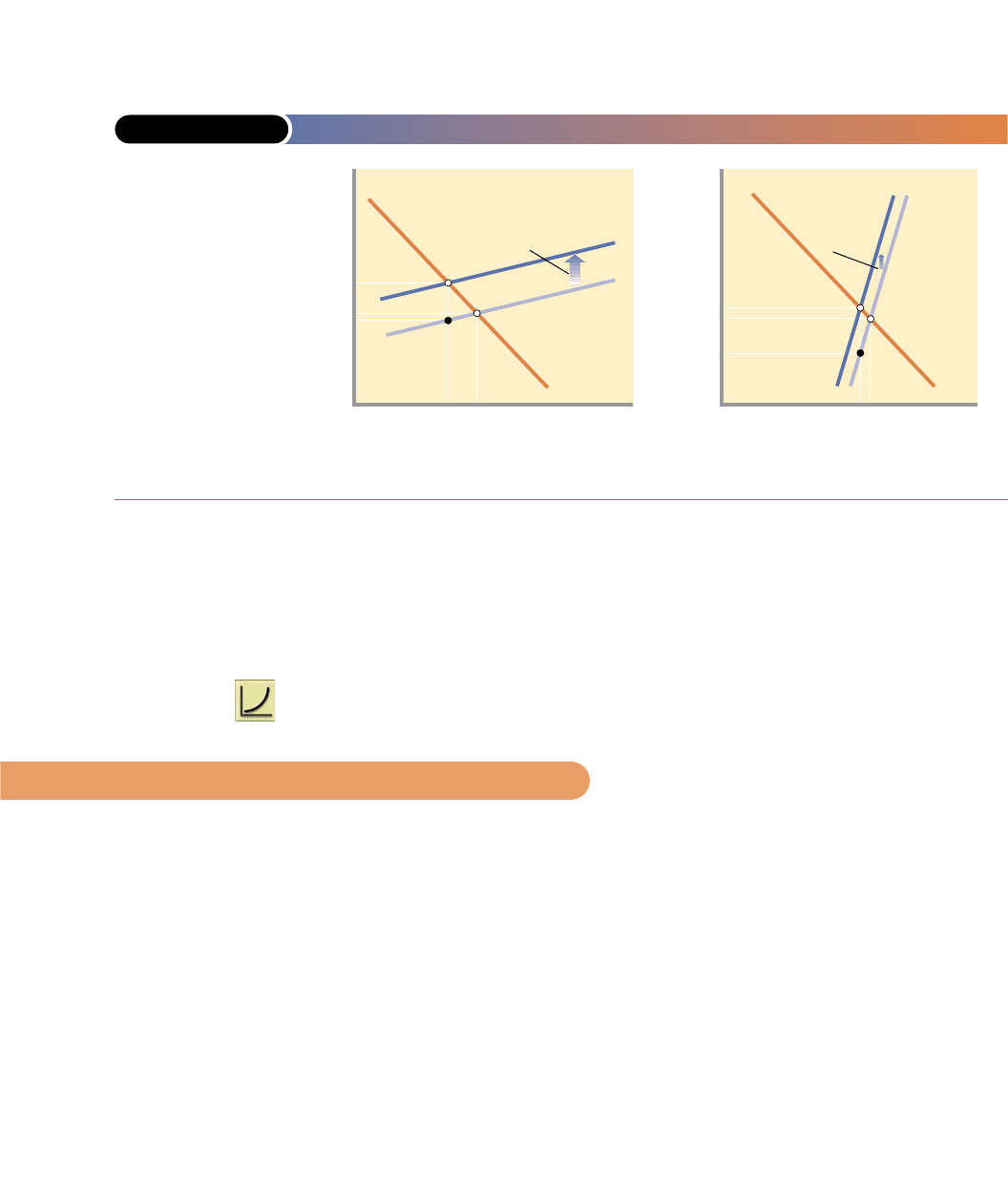

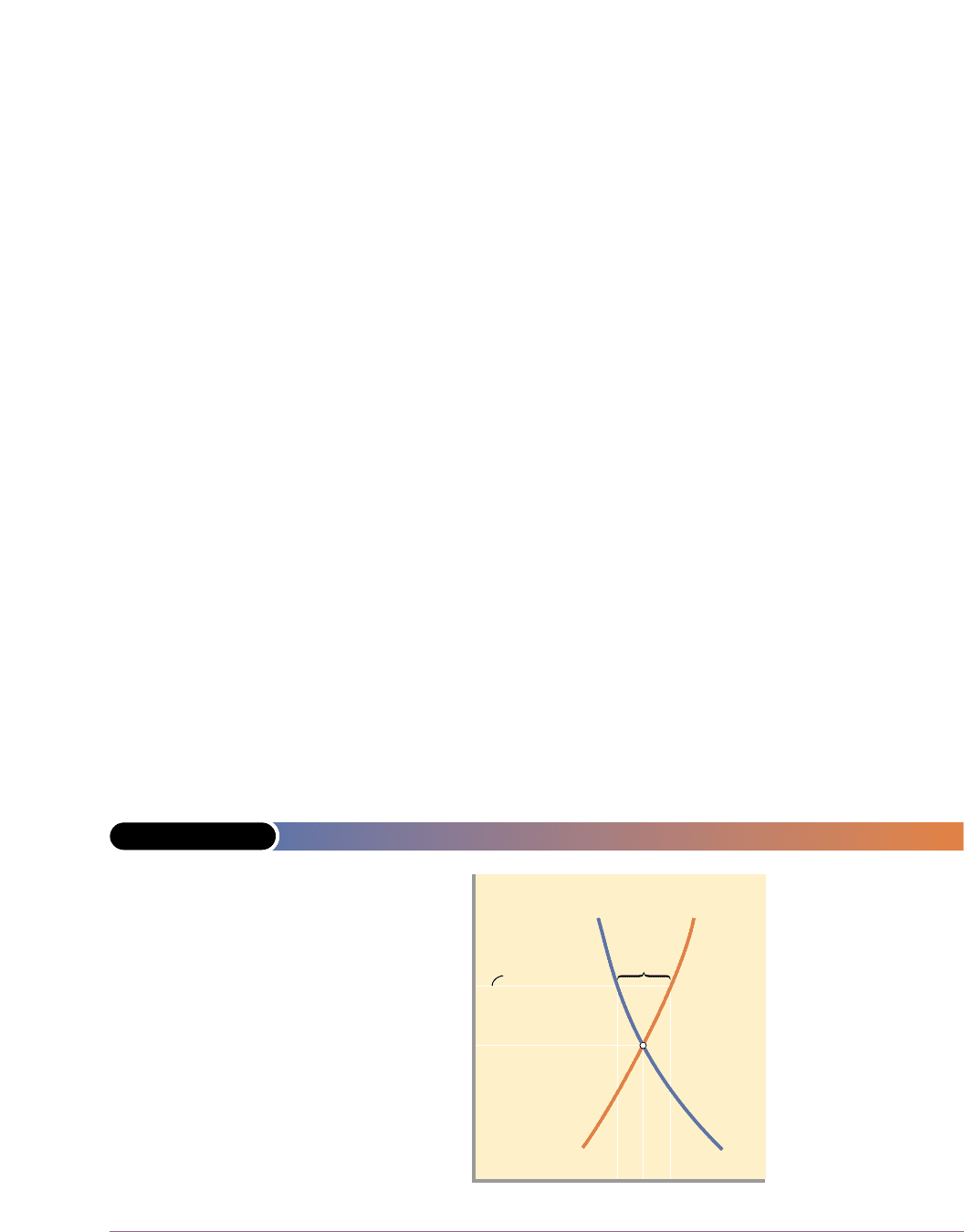

Second, with a specific demand, the more inelastic the supply, the larger the portion of

the tax borne by producers. When supply is elastic, as in Figure 6-6(a), most of the tax

(P

e

– P

1

) is shifted to consumers, and only a small portion (P

1

– P

a

) is borne by sell-

ers. But when supply is inelastic, as in Figure 6-6(b), the reverse is true; the major

144 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

FIGURE 6-5 DEMAND ELASTICITY AND THE INCIDENCE OF A TAX

P

P

e

P

a

P

1

0

Q

1

Q

0

Q

a

c

b

(a) Tax incidence and elastic

demand

P

P

i

P

b

P

1

0

Q

2

Q

1

Q

(b) Tax incidence and inelastic

demand

a

c

b

S

t

S

D

i

Tax

Tax

S

t

S

D

e

Panel (a): If demand

is elastic in the rele-

vant price range,

price rises modestly

(P

1

to P

e

) when a tax

is levied. Hence, the

producer bears most

of the tax burden.

Panel (b): If demand

is inelastic, the price

to the buyer will

increase substantially

(P

1

to P

i

) and most of

the tax will be shifted

to consumers.

<economics.about.com/

money/economics/library/

weekly/aa070897.htm>

Some simple economics

of the tobacco deal

portion of the tax (P

1

– P

b

) falls on sellers, and a relatively small amount (P

i

– P

1

) is

shifted to buyers. The equilibrium quantity also declines less with an inelastic sup-

ply than it does with an elastic supply.

Gold is an example of a product with an inelastic supply, one where the burden

of a tax would mainly fall on producers. Conversely, because the supply of baseballs

is elastic, producers would pass on to consumers much of a tax on baseballs.

You may want to reverse the analysis and assume that the government levies a

(sales) tax on consumers. (Key Question 14)

We turn now to another major supply and demand topic of our chapter: the impli-

cations of government-set prices. On occasion the public and the government con-

clude that supply and demand have resulted in prices that are either unfairly high

to buyers or unfairly low to sellers. In such instances the government may intervene

by legally limiting how high or low a price may go.

Price Ceilings and Shortages

A price ceiling is the maximum legal price a seller may charge for a product or serv-

ice. A price at or below the ceiling is legal; a price above it is not. The rationale for

establishing price ceilings (or ceiling prices) on specific products is that they pur-

portedly enable consumers to obtain some essential good or service that they could

not afford at the equilibrium price. Examples are rent controls and usury laws,

which specify maximum prices in the forms of rent and interest that can be charged

to borrowers. Also, the government has at times imposed price ceilings either on all

products or on a very wide range of products—so-called price controls—to try to

restrain inflation. Price controls were invoked during World War II and in the 1970s.

GRAPHICAL ANALYSIS

We can easily demonstrate the effects of price ceilings graphically. Let’s suppose

that rapidly rising world income boosts the purchase of automobiles and shifts the

chapter six • supply and demand: elasticities and government-set prices 145

FIGURE 6-6 SUPPLY ELASTICITY AND THE INCIDENCE OF A TAX

P

P

e

P

a

P

1

0

Q

1

Q

0

Q

(a) Tax incidence and elastic

supply

P

P

i

P

b

P

1

0

Q

1

Q

0

Q

(b) Tax incidence and inelastic

supply

a

c

b

S

t

S

D

Tax

Tax

a

c

b

S

t

S

D

Panel (a): With an

elastic supply an

excise tax results in a

large price increase

(P

1

to P

e

), and the

tax is therefore paid

mainly by consumers.

Panel (b): If supply is

inelastic, the price

rise is small (P

1

to P

i

),

and sellers will

have to bear most

of the tax.

Government-Set Prices

price ceiling

A legally estab-

lished maximum

price for a good or

service.

demand for gasoline to the right so that the equilibrium or market price reaches

$1.25 per litre, shown as P

0

in Figure 6-7. The rapidly rising price of gasoline greatly

burdens low-income and moderate-income households who pressure government

to “do something.” To keep gasoline affordable for these households, the govern-

ment imposes a ceiling price, P

c

, of $.75 per litre. To be effective, a price ceiling must

be below the equilibrium price. A ceiling price of $1.50, for example, would have no

immediate effect on the gasoline market.

What are the effects of this $.75 ceiling price? The rationing ability of the free

market is rendered ineffective. Because the ceiling price, P

c

, is below the market-

clearing price, P

0

, there is a lasting shortage of gasoline. The quantity of gasoline

demanded at P

c

is Q

d

and the quantity supplied is only Q

s

; a persistent excess

demand or shortage of amount Q

d

– Q

s

occurs.

The important point is that the price ceiling, P

c

, prevents the usual market adjust-

ment in which competition among buyers bids up price, inducing more production

and rationing some buyers out of the market. That process would continue until the

shortage disappeared at the equilibrium price and quantity, P

0

and Q

0

.

By preventing these market adjustments from occurring, the price ceiling poses

problems born of the market disequilibrium.

RATIONING PROBLEM

How will the government apportion the available supply, Q

s

, among buyers who

want the greater amount Q

d

? Should gasoline be distributed on a first-come, first-

served basis, that is, to those willing and able to get in line the soonest and to stay

in line? Or should gas stations distribute it on the basis of favouritism? Since an

unregulated shortage does not lead to an equitable distribution of gasoline, the gov-

ernment must establish some formal system for rationing it to consumers. One

option is to issue ration coupons, which authorize bearers to purchase a fixed

amount of gasoline per month. The rationing system would entail first the printing

of coupons for Q

s

litres of gasoline and then the equitable distribution of the

coupons among consumers so that the wealthy family of four and the poor family

of four both receive the same number of coupons.

146 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

FIGURE 6-7 A PRICE CEILING RESULTS IN A PERSISTENT

SHORTAGE

Shortage

P

0

Ceiling

Q

s

Q

d

Q

0

Q

P

c

P

0

$.75

$1.25

S

D

A price ceiling is a

maximum legal price,

such as P

c

, that is

below the equilibrium

price. It results in a

persistent product

shortage, here shown

by the distance

between Q

d

and Q

s

.

BLACK MARKETS

Ration coupons would not prevent a second problem from arising. The demand

curve in Figure 6-7 tells us that many buyers are willing to pay more than the ceiling

price P

c

, and, of course, it is more profitable for gasoline stations to sell at prices

above the ceiling. Thus, despite the sizable enforcement bureaucracy that will accom-

pany the price controls, black markets in which gasoline is illegally bought and sold

at prices above the legal limits will flourish. Counterfeiting of ration coupons will

also be a problem, and since the price of gasoline is now set by the government, there

would be political pressure on governments to set the price even lower.

RENT CONTROLS

Rent controls are maximum rents established by law (and recently, rent controls

have set maximum rent increases for existing tenants). Such laws are well intended;

their goals are to protect low-income families from escalating rents caused by per-

ceived housing shortages and to make housing more affordable to the poor.

When controls are first imposed, they usually restrict increases in rents above cur-

rent levels. The short-run supply curve for rental accommodation is inelastic

because it takes landlords some time to react to price changes and bring new units

on the market. Most tenants benefit, since the quantity of rental accommodation cur-

rently on the market or under construction is not significantly affected. Thus, the

program appears to be successful even if shortages begin to appear. Figure 6-8 por-

trays a market for rental accommodation with rents fixed at R

c

and a short-run sup-

ply curve, S

s

. A shortage Q

1

– Q

2

exists in the short run.

In the long run the shortage of rental accommodation will worsen since the sup-

ply of rental accommodation becomes more elastic. Construction of new units

decreases and landlords try to convert existing units to other uses or allow them to

deteriorate. The supply curve becomes more elastic in the long run, shown by S

L

in

Figure 6-8(b), making the shortage worse, and increasing it to Q

1

– Q

3

.

The gradually worsening shortage in the long run leads to several related prob-

lems. As in the case of controls on food prices, a black market will emerge. The black

chapter six • supply and demand: elasticities and government-set prices 147

FIGURE 6-8 RENT CONTROLS

S

S

Q

2

Q

1

Q

0

Q

2

Q

3

R

c

R

0

R

c

R

1

R

1

Q

1

Q

0

Short-run

shortage

Long-run

shortage

(a) Short run

(b) Long run

Quantity of rental accommodation

Quantity of rental accommodation

D

D

S

S

S

L

Rent (R)

Rent (R)

In the short run (panel

a) the supply for rental

accommodation is

inelastic. If rent controls

are set at R

c

, a shortage

of Q

1

– Q

2

will occur in

the short run. In the long

run (panel b), supply

becomes more elastic

as landlords are able to

add or withdraw rental

units from the market. In

the long run the shortage

will worsen to Q

1

– Q

3

.

On the black market,

rents of as much as R

1

will be charged.

black

markets

Markets in which

products are ille-

gally bought and

sold at prices above

the legal limits.

market in rental accommodation is often characterized by the charging of “key

money.” Prospective tenants are often forced to bribe a landlord or a subletting ten-

ant to acquire a particular rental unit. The acceptance of key money is illegal in most

jurisdictions with rent controls, but the practice is difficult to stamp out because it is

to the advantage of both parties. Those desperate for rental accommodation will have

to pay the black market rate of as much as R

1

, shown in Figure 6-8(b).

Another problem that results from controls is the emergence of a dual rental mar-

ket if new buildings are exempt from controls. Apartment units whose rents are

below market levels are almost always rented informally or with some form of key

money attached. The units that have recently come on the market will be offered at

rents above the levels that would exist without controls as landlords attempt to

compensate for future restrictions on rent increases. Because of discrimination by

landlords and the ability to pay key money, middle-class tenants will find it easier

to secure units in the controlled market, while the poor will be forced to seek units

in the uncontrolled market. Perversely, tenants with higher incomes can be the

major beneficiaries of the program.

Rent controls distort market signals and misallocate resources. Too few resources

are allocated to rental housing, too many to alternative uses. Ironically, although

rent controls are often legislated to lessen the effects of perceived housing shortages,

controls are a primary cause of such shortages.

CREDIT CARD INTEREST CEILINGS

Over the years there have been many calls for interest-rate ceilings on credit card

accounts. The usual rationale for interest-rate ceilings is that the banks and retail

stores issuing such cards are presumably taking unfair advantage of users and, in par-

ticular, lower-income users by charging interest rates that average about 18 percent.

What might be the responses to government imposing a below-equilibrium interest

rate on credit cards? The lower interest income associated with a legal interest ceiling

would require the issuers of cards to reduce their costs or enhance their revenues:

● Card issuers might tighten credit standards to reduce losses due to non-

payment and collection costs. Then, low-income people and young people

who have not yet established their creditworthiness would find it more diffi-

cult to obtain credit cards.

● The annual fee charged to cardholders might be increased, as might the fee

charged to merchants for processing credit card sales. Similarly, card users

might be charged a fee for every transaction.

● Card users now have a post-purchase grace period during which the credit

provided is interest-free. That period might be shortened or eliminated.

● Certain “enhancements” that accompany some credit cards (for example,

extended warranties on products bought with a card) might be eliminated.

● Retail stores that issue their own cards might increase their prices to help off-

set the decline of interest income; customers who pay cash would in effect be

subsidizing customers who use credit cards.

Price Floors and Surpluses

Price floors are minimum prices fixed by the government. A price at or above the

price floor is legal; a price below it is not. Price floors above equilibrium prices are

usually invoked when society believes that the free functioning of the market

148 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

price

floors

Legally

determined prices

above equilibrium

prices.

system has not provided a sufficient income for certain groups of resource suppli-

ers or producers. Formerly supported prices for agricultural products and current

minimum wages are two examples of price (or wage) floors. Let’s look at the former.

Suppose the equilibrium price for wheat is $3 per bushel and, because of that low

price, many farmers have extremely low incomes. The government decides to help

by establishing a legal price floor or price support of $4 per bushel.

What will be the effects? At any price above the equilibrium price, quantity sup-

plied will exceed quantity demanded—that is, there will be a persistent excess sup-

ply or surplus of the product. Farmers will be willing to produce and offer for sale

more than private buyers are willing to purchase at the price floor. As we saw with a

price ceiling, an imposed legal price disrupts the rationing ability of the free market.

Figure 6-9 illustrates the effect of a price floor. Suppose that S and D are the sup-

ply and demand curves for corn. Equilibrium price and quantity are P

0

and Q

0

,

respectively. If the government imposes a price floor of P

f

, farmers will produce Q

s

,

but private buyers will purchase only Q

d

. The surplus is the excess of Q

s

over Q

d

.

The government can cope with the surplus resulting from a price floor in only

two ways:

1. It can restrict supply (for example, by asking farmers to agree to take a certain

amount of land out of production) or increase demand (for example, by research-

ing new uses for the product involved). These actions may reduce the difference

between the equilibrium price and the price floor and thereby reduce the size of

the resulting surplus.

2. The government can purchase the surplus output at the $4 price (thereby subsi-

dizing farmers) and store or otherwise dispose of it.

Controversial Tradeoffs

In a free market, the competitive forces match the supply decisions of producers and

the demand decisions of buyers, but price ceilings and floors interfere with such an

outcome. The government must provide a rationing system to handle product

chapter six • supply and demand: elasticities and government-set prices 149

FIGURE 6-9 A PRICE FLOOR RESULTS IN A PERSISTENT SURPLUS

P

f

P

0

Surplus

Floor

P

Q

d

Q

0

Q

s

0

Q

S

D

$2.00

$3.00

A price floor is a

minimum legal price,

such as P

f

, which

results in a persistent

product surplus, here

shown by the hori-

zontal distance

between Q

s

and Q

d

.