McConnell Campbell R., Brue Stanley L., Barbiero Thomas P. Microeconomics. Ninth Edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

shortages stemming from price ceilings and devise ways to eliminate product sur-

pluses arising from price floors. Legal maximum and minimum prices thus entail

controversial tradeoffs. The alleged benefits of price ceilings to consumers and price

floors to producers must be balanced against the costs associated with the conse-

quent shortages and surpluses.

Our discussion of price controls, rent controls, and interest-rate ceilings on credit

cards shows that government interference with the market can have unintended,

undesirable side effects. Price controls, for example, create illegal black markets.

Rent controls may discourage housing construction and repair. Instead of protect-

ing low-income families from higher interest charges, interest-rate ceilings may sim-

ply deny credit to those families. For all these reasons, economists generally oppose

government-imposed prices.

150 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

● Price elasticity of supply measures the sensitiv-

ity of suppliers to changes in the price of a prod-

uct. The price elasticity of supply coefficient E

s

is the ratio of the percentage change in quantity

supplied to the percentage change in price.

The elasticity of supply varies directly with the

amount of time producers have to respond to

the price change.

● The cross elasticity of demand coefficient E

xy

is computed as the percentage change in the

quantity demanded of product X divided by the

percentage change in the price of product Y. If

the cross elasticity coefficient is positive, the

two products are substitutes; if it is negative,

they are complements.

● The income elasticity coefficient E

i

is computed

as the percentage change in quantity de-

manded divided by the percentage change in

income. A positive coefficient indicates a nor-

mal or superior good. The coefficient is nega-

tive for an inferior good.

● Government-controlled prices in the form of

ceilings and floors stifle the rationing function

of prices and cause unintended side effects.

Advances in medical technology

make it possible for surgeons to

replace some human body parts

with donated used parts, much

like a mechanic might replace a

worn-out alternator in an auto-

mobile with one from a junked

vehicle. It has become increas-

ingly commonplace in medicine

to transplant kidneys, lungs, liv-

ers, eye corneas, pancreases,

and hearts from deceased indi-

viduals to those whose organs

have failed or are failing. But

surgeons and many of their pa-

tients face a growing problem:

too few donated organs are

available for transplant. Not

everyone who needs a trans-

plant can get one. Indeed, an in-

adequate supply of donated or-

gans causes an estimated 400

Canadian deaths per year.

Why Shortages? Seldom, if

ever, do we hear of shortages of

used auto parts such as alterna-

tors, batteries, transmissions, or

water pumps. What is different

about organs for transplant?

A MARKET FOR HUMAN ORGANS?

A market might eliminate the present shortage of

human organs for transplant. But many serious

objections exist to turning human body parts into

commodities for purchase and sale.

chapter six • supply and demand: elasticities and government-set prices 151

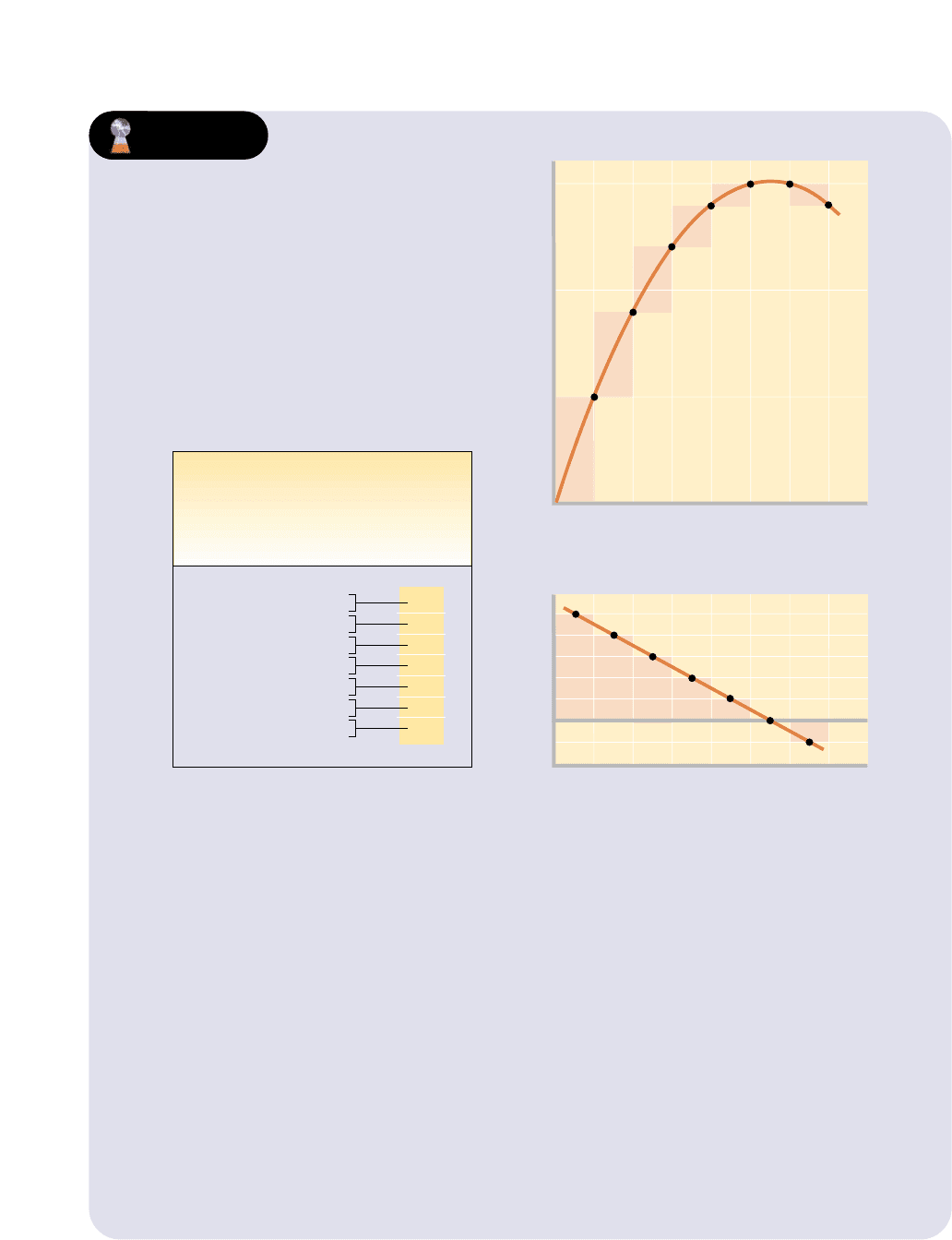

One difference is that a market

exists for used auto parts but

not for human organs. To under-

stand this situation, observe the

demand curve D

1

and supply

curve S

1

in the accompanying

figure. The downward slope of

the demand curve tells us that if

there were a market for human

organs, the quantity of organs

demanded would be greater at

lower prices than at higher

prices. Perfectly inelastic supply

curve S

1

represents the fixed

quantity of human organs now

donated via consent before

death. Because the price of these

donated organs is in effect zero,

quantity demanded, Q

3

, exceeds

quantity supplied, Q

1

. The short-

age of Q

3

– Q

1

is rationed

through a waiting list of those

in medical need of transplants.

Many people die while still on

the waiting list.

Use of a Market A market for

human organs would increase

the incentive to donate organs.

Such a market might work like

this: An individual might specify

in a legal document a willing-

ness to sell one or more usable

human organs on death or brain

death. The person could specify

where the money from the sale

would go, for example, to family,

a church, an educational institu-

tion, or a charity. Firms would

then emerge to purchase organs

and resell them where needed

for profit. Under such a system,

the supply curve of usable or-

gans would take on the normal

upward slope of typical supply

curves. The higher the expected

price of an organ, the greater the

number of people willing to

have their organs sold at death.

Suppose that the supply curve is

S

2

in the figure. At the equilib-

rium price P

1

, the number of or-

gans made available for trans-

plant (Q

2

) would equal the

number purchased for trans-

plant (also Q

2

). In this general-

ized case, the shortage of organs

would be eliminated and, of par-

ticular importance, the number

of organs available for trans-

planting would rise from Q

1

to

Q

2

. More lives would be saved

and enhanced than is the case

under the present donor system.

Objections In view of this posi-

tive outcome, why is there no

such market for human organs?

Critics of market-based solutions

have two main objections. The

first is a moral objection: Critics

feel that turning human organs

into commodities commercial-

izes human beings and dimin-

ishes the special nature of

human life. They say there is

something unseemly about sell-

ing and buying body organs as if

they were bushels of wheat or

ounces of gold. Moreover, critics

note that the market would ra-

tion the available organs (as rep-

resented by Q

2

in the figure) to

people who either can afford

them (at P

1

) or have health insur-

ance for transplants.

Second, a health cost objec-

tion suggests that a market for

body organs would greatly in-

crease the cost of health care.

Rather than obtaining freely do-

nated (although too few) body

organs, patients would have to

pay market prices for them,

increasing the cost of medical

care. As transplant procedures

are further perfected, the de-

mand for transplants is expected

to increase significantly. Rapid

increases in demand relative to

supply would boost the prices of

human organs and thus further

contribute to the problem of es-

calating health care costs.

Supporters of market-based

solutions to organ shortages

point out that the market is sim-

ply being driven underground.

Worldwide, an estimated $1 bil-

lion annual illegal market in

human organs has emerged. As

in other illegal markets, the

unscrupulous tend to thrive.

Those who support legalization

say that it would be greatly

preferable to legalize and regu-

late the market for the laws

against selling transplantable

human organs.

P

0

P

1

P

Q

1

Q

2

Q

3

Q

S

2

S

1

D

1

chapter summary

terms and concepts

152 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

1. Price elasticity of demand measures con-

sumer response to price changes. If con-

sumers are relatively sensitive to price

changes, demand is elastic. If they are rela-

tively unresponsive to price changes, de-

mand is inelastic.

2. The price elasticity coefficient E

d

measures the

degree of elasticity or inelasticity of demand.

The coefficient is found by the formula

E

d

=

percentage change in

Economists use the averages of prices and

quantities under consideration as reference

points in determining percentage changes

in price and quantity. If E

d

is greater than

one, demand is elastic. If E

d

is less than one,

demand is inelastic. Unit elasticity is the spe-

cial case in which E

d

equals one.

3. Perfectly inelastic demand is graphed as a

line parallel to the vertical axis; perfectly

elastic demand is shown by a line above and

parallel to the horizontal axis.

4. Elasticity varies at different price ranges on a

demand curve, tending to be elastic in the

upper left segment and inelastic in the lower

right segment. Elasticity cannot be judged by

the steepness or flatness of a demand curve.

5. If total revenue changes in the opposite

direction from prices, demand is elastic. If

price and total revenue change in the same

direction, demand is inelastic. Where demand

is of unit elasticity, a change in prices leaves

total revenue unchanged.

6. The number of available substitutes, the size

of an item’s price relative to one’s budget,

whether the product is a luxury or a neces-

sity, and the time given to adjust are all

determinants of elasticity of demand.

7. The elasticity concept also applies to supply.

The coefficient of price elasticity of supply is

found by the formula

E

s

=

percentage change in

The averages of the price and quantities

under consideration are used as reference

points for computing percentage changes.

Elasticity of supply depends on the ease of

shifting resources between alternative uses,

which in turn varies directly with the time

producers have to adjust to a particular price

change.

8. Cross elasticity of demand indicates how

sensitive the purchase of one product is to

changes in the price of another product. The

coefficient of cross elasticity of demand is

found by the formula

E

xy

=

percentage change in

Positive cross elasticity of demand identifies

substitute goods; negative cross elasticity

identifies complementary goods.

9. Income elasticity of demand indicates the

responsiveness of consumer purchases to a

change in income. The coefficient of income

elasticity of demand is found by the formula

E

i

=

percentage change in

The coefficient is positive for normal goods

and negative for inferior goods.

10. Legally fixed prices stifle the rationing func-

tion of equilibrium prices. Effective price

ceilings result in persistent product short-

ages, and if an equitable distribution of the

product is sought, government must ration

the product to consumers. Price floors lead

to product surpluses; the government must

either purchase these surpluses or eliminate

them by imposing restrictions on production

or by increasing private demand.

quantity demanded of X

ᎏᎏᎏᎏ

percentage change in income

quantity demanded of X

ᎏᎏᎏᎏ

percentage change in price of Y

quantity supplied of X

ᎏᎏᎏᎏ

percentage change in price of X

quantity demanded of X

ᎏᎏᎏᎏ

percentage change in price of X

price elasticity of demand,

p. 127

elastic demand, p. 128

inelastic demand, p. 128

unit elasticity, p. 128

perfectly inelastic demand,

p. 129

perfectly elastic demand,

p. 129

total revenue (TR), p. 132

total-revenue test, p. 132

price elasticity of supply,

p. 138

market period, p. 139

short run, p. 140

chapter six • supply and demand: elasticities and government-set prices 153

study questions

1. Explain why the choice between discussing

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 units or 1000, 2000,

3000, 4000, 5000, 6000, 7000, and 8000

movie tickets makes no difference in deter-

mining elasticity in Table 6-1.

2.

KEY QUESTION Graph the accompa-

nying demand data and then use the mid-

point formula for E

d

to determine price

elasticity of demand for each of the four pos-

sible $1 price changes. What can you con-

clude about the relationship between the

slope of a curve and its elasticity? Explain in

a nontechnical way why demand is elastic in

the northwest segment of the demand curve

and inelastic in the southeast segment.

Product price Quantity demanded

$5 1

42

33

24

15

3. Draw two linear demand curves parallel to

one another. Demonstrate that for any spe-

cific price change, demand is more elastic on

the curve closer to the origin.

4.

KEY QUESTION Calculate total-

revenue data from the demand schedule in

question 2. Graph total revenue below your

demand curve. Generalize about the rela-

tionship between price elasticity and total

revenue.

5.

KEY QUESTION How would the fol-

lowing changes in price affect total revenue?

That is, would total revenue increase,

decline, or remain unchanged?

a. Price falls and demand is inelastic.

b. Price rises and demand is elastic.

c. Price rises and supply is elastic.

d. Price rises and supply is inelastic.

e. Price rises and demand is inelastic.

f. Price falls and demand is elastic.

g. Price falls and demand is unit elastic.

6.

KEY QUESTION What are the major

determinants of price elasticity of demand?

Use those determinants and your own rea-

soning in judging whether demand for each

of the following products is probably elastic

or inelastic: (a) bottled water, (b) toothpaste,

(c) Crest toothpaste, (d) ketchup, (e) dia-

mond bracelets, (f) Microsoft Windows oper-

ating system.

7. What effect would a rule stating that univer-

sity students must live in university dormito-

ries have on the price elasticity of demand

for dormitory space? What impact might this

in turn have on room rates?

8. “If the demand for farm products is highly

price inelastic, a large crop yield may reduce

farm incomes.” Evaluate this statement and

illustrate it graphically.

9. You are chairperson of a provincial tax com-

mission responsible for establishing a pro-

gram to raise new revenue through sales

taxes. Would elasticity of demand be impor-

tant to you in determining on which prod-

ucts the taxes should be levied? Explain.

10.

KEY QUESTION In November 1998

Vincent van Gogh’s self-portrait sold at auc-

tion for $71.5 million. Portray this sale in a

demand and supply diagram and comment

on the elasticity of supply. Comedian George

Carlin once mused, “If a painting can be

forged well enough to fool some experts,

why is the original so valuable?” Provide an

answer.

11. Because of a legal settlement over state

health care claims, in 1999 the tobacco com-

panies had to raise the average price of a

pack of cigarettes from $1.95 to $2.45. The

projected decline in cigarette sales was 8

percent. What does this imply about the

elasticity of demand for cigarettes? Explain.

12.

KEY QUESTION Suppose the cross

elasticity of demand for products A and B is

+3.6 and for products C and D is –5.4. What

can you conclude about how products A and

B are related? products C and D?

13.

KEY QUESTION The income elastici-

ties of demand for movies, dental services,

long run, p. 140

cross elasticity of demand,

p. 140

income elasticity of demand,

p. 141

price ceiling, p. 145

black markets, p. 147

price floors, p. 148

154 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

and clothing have been estimated to be +3.4,

+1.0, and +0.5, respectively. Interpret these

coefficients. What does it mean if an income

elasticity coefficient is negative?

14.

KEY QUESTION What is the incidence

of a tax when demand is highly inelastic?

highly elastic? What effect does the elasticity

of supply have on the incidence of a tax?

15. A recent study found that an increase in the

price of beer would reduce the amount of

marijuana consumed. Is cross elasticity of

demand between the two products positive

or is it negative? Are these products substi-

tutes, or are they complements? What might

be the logic behind this relationship?

16. Why is it desirable for price ceilings to

be accompanied by government rationing?

Why is it desirable for price floors to be

accompanied by programs that purchase

surpluses, restrict output, or increase de-

mand? Show graphically why price ceilings

produce shortages and price floors cause

surpluses.

17. (The Last Word) Do you favour the estab-

lishment of a market for donated human

organs? Why or why not?

internet application questions

1. Generally, the elasticity of demand for a

product will be greater (a) the larger the

number of substitutes, (b) the greater the

proportion of income an item takes, and

(c) the less the item is considered to be a

necessity. Kmart, <www.kmart.com>, posts a

weekly sales circular on selected merchan-

dise, organized by department. It must con-

clude that the demand for these Blue Light

Specials is elastic: the decrease in price will

increase total revenue. Check out this week’s

specials and, for each item, give it one point

for meeting the criterion of each determinant

above. How many specials score a three? Do

any score zero? Why would Kmart include

any item that scored less than a three?

2. Rent controls in Ontario began in the 1970s.

The Tenant Act was revised in the late 1990s.

Visit the Ontario Rental Housing Information

Web site at <www.rental-housing.com/canada/

ontpage.htm> to see a summary of existing

laws. What would be the likely attitude of

each of the following groups toward the rent

stabilization program: current renters, people

looking for an apartment to rent in Ontario?

IN THIS CHAPTER

IN THIS CHAPTER

Y

Y

OU WILL LEARN:

OU WILL LEARN:

The two explanations

for why the demand curve

is downward sloping.

•

The theory of consumer choice.

•

About utility maximization and

the demand curve.

•

To apply marginal utility

theory to real-world situations.

The Theory

of Consumer

Choice

I

f you were to compare the shopping carts

of almost any two consumers, you would

observe striking differences. Why does

Paula have potatoes, peaches, and Pepsi in

her cart while Sam has sugar, saltines, and 7-

Up in his? Why didn’t Paula also buy pasta

and plums? Why didn’t Sam have soup and

spaghetti on his grocery list?

In this chapter, you will see how individual

consumers allocate their income among the

various goods and services available to them.

Given a particular budget, how does a con-

sumer decide what goods and services to buy?

Why does the typical consumer buy more of a

product when its price falls? As we answer

these questions, you will also strengthen your

understanding of the law of demand.

SEVEN

The law of demand is based on common sense. A high price discourages consumers

from buying; a low price encourages them to buy. In Chapter 3 we mentioned two

explanations of the downward-sloping demand curve (income and substitution

effects and the law of diminishing marginal utility) that supported this observation.

We now want to say more about these explanations in the context of consumer

behaviour, the subject of this chapter. A third explanation, based on indifference

curves, is more advanced and is summarized in the appendix to this chapter.

Income and Substitution Effects

Our first explanation of the downward slope of the demand curve involves the

income and substitution effects.

THE INCOME EFFECT

The income effect is the impact that a change in a product’s price has on a consumer’s

real income and, consequently, on the quantity of that good demanded. Let’s suppose

our product is a coffee drink such as a latte or cappuccino. If the price of such drinks

declines, the real income or purchasing power of anyone who buys them increases; that

is, they are able to buy more with the same nominal income. The increase in real income

will be reflected in increased purchases of many normal goods, including coffee drinks.

For example, with a constant money income of $20 every two weeks, you can buy

10 coffee drinks at $2 each. If their price falls to $1 apiece and you buy 10 of them,

you will have $10 per week left over to buy more coffee drinks and other goods. A

decline in the price of coffee drinks increases consumers’ real income, enabling them

to purchase more coffee drinks. This relationship is the income effect.

THE SUBSTITUTION EFFECT

The substitution effect is the impact that a change in a product’s price has on its rel-

ative expensiveness, and, consequently, on the quantity demanded. When the price

of a product falls, that product becomes cheaper relative to all other products. Con-

sumers will substitute the cheaper product for other products that are now rela-

tively more expensive. In our example, if the prices of other products remain

unchanged and the price of coffee drinks falls, lattes and cappuccinos become more

attractive to the buyer. Coffee drinks are a relatively better buy at $1 than at $2. The

lower price will induce the consumer to substitute coffee drinks for some of the now

relatively less attractive items in the budget—perhaps colas, bottled water, or iced

tea. Because a lower price increases the relative attractiveness of a product, the con-

sumer buys more of it. This relationship is the substitution effect.

The income and substitution effects combine to increase a consumer’s ability and

willingness to buy more of a specific good when its price falls.

Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility

A second explanation of the downward-sloping demand curve is that, although con-

sumer wants in general may be insatiable, wants for particular commodities can be

satisfied. In a specific span of time over which consumers’ tastes remain unchanged,

consumers can get as much of a particular good or service as they can afford. But,

the more of that product they obtain, the less additional product they want.

Consider durable goods, for example. Consumers’ desires for an automobile,

when they have none, may be very strong, but the desire for a second car is less

156 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

A Closer Look at the Law of Demand

income

effect

A

change in the

quantity demanded

of a product that

results from the

change in real

income (purchasing

power) produced by

a change in the

product’s price.

substitu-

tion effect

A change in the

quantity demanded

of a consumer good

that results from a

change in its

relative expensive-

ness produced by a

change in the

product’s price, or

the effect of a

change in the price

of a resource on the

quantity of the

resource employed

by a firm, assuming

no change in its

output.

Choosing

a Little More

or Less

intense, and for a third or fourth, weaker and weaker. Unless they are collectors,

even the wealthiest families rarely have more than a half-dozen cars, although their

income would allow them to purchase a whole fleet of vehicles.

TERMINOLOGY

Evidence indicates that consumers can fulfill specific wants with succeeding units

of a commodity but that each added unit provides less utility than the previous unit

purchased. Recall that a product has utility if it can satisfy a want: utility is want-

satisfying power. The utility of a good or service is the satisfaction or pleasure one

gets from consuming it. Three characteristics of this concept must be emphasized:

1. “Utility” and “usefulness” are not synonymous. Paintings by Picasso may

offer great utility to art connoisseurs but are useless functionally (other than

for hiding a crack in a wall).

2. Implied in the first characteristic is the fact that utility is subjective. The utility

of a specific product may vary widely from person to person. A jacked-up truck

may have great utility to someone who drives off-road but little utility to some-

one too old to climb into the rig. Eyeglasses have tremendous utility to some-

one who has poor eyesight but no utility at all to a person with 20/20 vision.

3. Because utility is subjective, it is difficult to quantify. But for purposes of illus-

tration, we assume that people can measure satisfaction with units called utils

(units of utility). For example, a particular consumer may get 100 utils of sat-

isfaction from a smoothie, 10 utils of satisfaction from a candy bar, and 1 util

of satisfaction from a stick of gum. These imaginary units of satisfaction are

convenient for quantifying consumer behaviour.

TOTAL UTILITY AND MARGINAL UTILITY

We must distinguish carefully between total utility and marginal utility. Total utility

is the total amount of satisfaction or pleasure a person derives from consuming some

specific quantity—for example, 10 units—of a good or service. Marginal utility is the

extra satisfaction a consumer realizes from one additional unit of that product, for ex-

ample, from the 11th unit. Alternatively, we can say that marginal utility is the change

in total utility that results from the consumption of one more unit of a product.

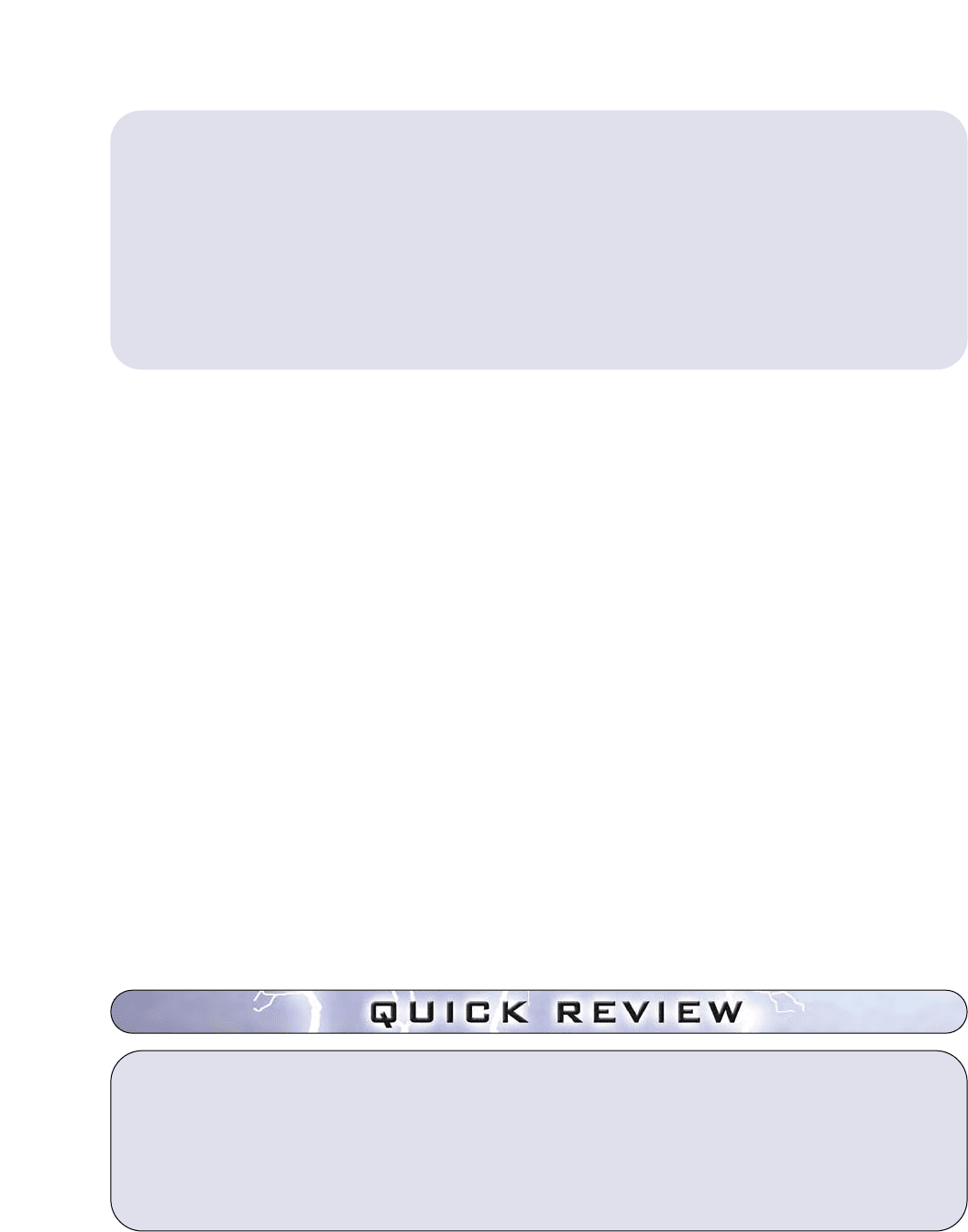

Figure 7-1 (Key Graph) and the accompanying table reveal the relation between

total utility and marginal utility. We have drawn the curves from the data in the

table. Column 2 shows the total utility associated with each level of consumption of

this particular product, tacos; column 3 shows the marginal utility—the change in

total utility—that results from the consumption of each successive taco. Starting at

the origin in Figure 7-1(a), we observe that each of the first five units increases total

utility (TU) but by a diminishing amount. Total utility reaches a maximum at the

sixth unit and then declines.

So, in Figure 7-1(b) we find that marginal utility (MU) remains positive but dimin-

ishes through the first five units (because total utility increases at a declining rate). Mar-

ginal utility is zero for the sixth unit (because that unit doesn’t change total utility).

Marginal utility then becomes negative with the seventh unit as the diner becomes ill

(because total utility is falling). Figure 7-1(b) and table column 3 tell us that each suc-

cessive taco yields less extra utility, meaning fewer utils, than the preceding one as the

consumer’s want for tacos comes closer and closer to fulfillment.

1

The principle that

chapter seven • the theory of consumer choice 157

utility The

want-satisfying

power of a good

or service; the

satisfaction or

pleasure a consumer

obtains from the

consumption of a

good or service.

total

utility

The

total amount of

satisfaction derived

from the consump-

tion of a single

product or a combi-

nation of products.

marginal

utility

The

extra utility a

consumer obtains

from the consump-

tion of one addi-

tional unit of a good

or service; equal to

the change in total

utility divided by

the change in the

quantity consumed.

<www.leavingcert.net/

serve/cont.php3?pg=

EC3DAU0493>

A discussion of

demand and utility

1

In Figure 7-1(b) we graphed marginal utility at half-units. For example, we graphed the marginal

utility of 4 utils at 3

1

⁄2 units because the 4 utils refers neither to the third nor the fourth unit per se

but to the addition or subtraction of the fourth unit.

158 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

30

20

10

01234567

Units consumed per meal

(a) Total utility

Total utility (utils)

10

8

6

4

2

-

2

0

12345

67

Units consumed per meal

(b) Marginal utility

(3)

Marginal

utility,

utils

(2)

Total

utility,

utils

10

00

(1)

Tacos

consumed

per meal

Marginal utility (utils)

8

101

6

182

4

243

2

284

0

305

-

2

306

287

MU

TU

Curves TU and MU are graphed from the data in the

table. Panel (a): As more of a product is consumed,

total utility increases at a diminishing rate, reaches

a maximum, and then declines. Panel (b): Marginal

utility, by definition, reflects the changes in total util-

ity. Thus marginal utility diminishes with increased

consumption, becomes zero when total utility is at a

maximum, and is negative when total utility declines.

As shown by the shaded rectangles in panels (a) and

(b), marginal utility is the change in total utility asso-

ciated with each additional taco. Or, alternatively,

each new level of total utility is found by adding

marginal utility to the preceding level of total utility.

FIGURE 7-1 TOTAL AND MARGINAL UTILITY

Key Graph

Quick Quiz

1. Marginal utility

a. is the extra output a firm obtains when it adds another unit of labour.

b. explains why product supply curves slope upward.

c. typically rises as successive units of a good are consumed.

d. is the extra satisfaction from the consumption of one more unit of some good

or service.

2. Marginal utility in Figure 7-1(b) is positive, but declining, when total util-

ity in Figure 7-1(a) is positive and

a. rising at an increasing rate.

b. falling at an increasing rate.

c. rising at a decreasing rate.

d. falling at a decreasing rate.

3. When marginal utility is zero in panel (b), total utility in panel (a) is

a. also zero.

b. neither rising nor falling.

marginal utility declines as the consumer acquires additional units of a given prod-

uct is known as the law of diminishing marginal utility. (Key Question 2)

MARGINAL UTILITY, DEMAND, AND ELASTICITY

How does the law of diminishing marginal utility explain why the demand curve

for a given product slopes downward? The answer is that, if successive units of a

good yield smaller and smaller amounts of marginal, or extra, utility, then the con-

sumer will buy additional units of a product only if its price falls. The consumer for

whom Figure 7-1 is relevant may buy two tacos at a price of $1 each, but because less

marginal utility is obtained from additional tacos, the consumer will choose not to

buy more at that price. The consumer would rather spend additional dollars on

products that provide more (or equal) utility, not less utility. Therefore, additional

tacos with less utility are not worth buying unless the price declines. (When mar-

ginal utility becomes negative, the restaurant would have to pay you to consume

another taco!) Thus, diminishing marginal utility supports the idea that price must

decrease for quantity demanded to increase. In other words, consumers behave in

ways that make demand curves downward sloping.

The amount by which marginal utility declines as more units of a product are con-

sumed helps us to determine that product’s price elasticity of demand. Other things

equal, if marginal utility falls sharply as successive units of a product are consumed,

demand is inelastic. A given decline in price will elicit only a relatively small increase

in quantity demanded, since the MU of extra units falls so rapidly. Conversely, mod-

est declines in marginal utility as consumption increases imply an elastic demand. A

particular decline in price will entice consumers to buy considerably more units of

the product, since the MU of additional units declines so slowly.

law of

diminishing

marginal

utility

As a

consumer increases

the consumption of

a good or service,

the marginal utility

obtained from each

additional unit of

the good or service

decreases.

c. negative.

d. rising but at a declining rate.

4. Suppose the person represented by these graphs experienced a dimin-

ished taste for tacos. As a result the

a. TU curve would get steeper.

b. MU curve would get flatter.

c. TU and MU curves would shift downward.

d. MU curve, but not the TU curve, would collapse to the horizontal axis.

Answers

1. d; 2. c; 3. b; 4. c

chapter seven • the theory of consumer choice 159

● The law of demand can be explained in terms

of the income effect (a decline in price raises the

consumer’s purchasing power) and the substi-

tution effect (a product whose price falls is sub-

stituted for other products).

● Utility is the benefit or satisfaction a person

receives from consuming a good or a service.

● The law of diminishing marginal utility indi-

cates that gains in satisfaction become smaller

as successive units of a specific product are

consumed.

● Diminishing marginal utility provides another

rationale for the law of demand, as well as one

for differing price elasticities.