McConnell Campbell R., Brue Stanley L., Barbiero Thomas P. Microeconomics. Ninth Edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

In addition to explaining the law of demand, the idea of diminishing marginal util-

ity explains how consumers allocate their money income among the many goods

and services available for purchase.

Consumer Choice and Budget Constraint

The typical consumer’s situation has the following dimensions.

● Rational behaviour Consumers are rational people who try to use their

money incomes to derive the greatest amount of satisfaction, or utility, from

them. Consumers want to get the most for their money or, technically, to max-

imize their total utility. They engage in rational behaviour.

● Preferences Each consumer has clear-cut preferences for certain goods and

services of those available in the market. We assume buyers also have a good

idea of how much marginal utility they will get from successive units of the

various products they purchase.

● Budget constraint At any point in time the consumer has a fixed, limited

amount of money income. Since each consumer supplies a finite amount of

human and property resources to society, each earns only limited income.

Thus, every consumer faces what economists call a budget constraint (budget

limitation), even those who earn millions of dollars a year. Of course, those

budget constraints are more severe for consumers with average incomes than

for those with extraordinarily high incomes.

● Prices Goods are scarce relative to the demand for them, so every good car-

ries a price tag. We assume that those price tags are not affected by the

amounts of specific goods that each person buys. After all, each person’s pur-

chase is a minuscule part of total demand, and since the consumer has a lim-

ited number of dollars, each can buy only a limited amount of goods.

Consumers cannot buy everything they want. This point drives home the real-

ity of scarcity to each consumer.

So the consumer must compromise and must choose the most satisfying mix of

goods and services. Different individuals will choose different mixes. As Global Per-

spective 7.1 shows, the mix may vary from nation to nation.

Utility-Maximizing Rule

Of all the different combinations of goods and services consumers can obtain within

their budgets, which specific combination will yield the maximum utility or satis-

faction for each person? To maximize satisfaction, consumers should allocate their

money income so that the last dollar spent on each product yields the same amount of extra

(marginal) utility. We call this the utility-maximizing rule. When the consumer has

balanced his or her margins using this rule, no incentive exists to alter the expendi-

ture pattern. The consumer is in equilibrium and would be worse off—total utility

would decline—if any alteration occurred in the bundle of goods purchased, pro-

viding no change occurs in taste, income, products, or prices.

Numerical Example

An illustration will help explain the utility-maximizing rule. For simplicity our exam-

ple is limited to two products, but the analysis would apply if there were more.

160 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

Theory of Consumer Choice

rational

behaviour

Human behaviour

based on compari-

son of marginal

costs and marginal

benefits; behaviour

designed to

maximize total

utility.

budget

constraint

The limit that the

size of a consumer’s

income (and the

prices that must be

paid for goods and

services) imposes

on the ability of that

consumer to obtain

goods and services.

utility-

maximizing

rule

To obtain

the greatest utility,

the consumer

should allocate

money income so

that the last dollar

spent on each

good or service

yields the same

marginal utility.

Choosing

a Little More

or Less

Suppose consumer Holly is trying to decide which combination of two products she

should purchase with her fixed daily income of $10. These products might be aspara-

gus and breadsticks, apricots and bananas, or apples and broccoli. Let’s just call them

A and B.

Holly’s preferences for products A and B and their prices are the basic data deter-

mining the combination that will maximize her satisfaction. Table 7-1 summarizes

those data, with column 2(a) showing the amount of marginal utility Holly will

derive from each successive unit of A and column 3(a) showing the same thing for

product B. Both columns reflect the law of diminishing marginal utility, which is

assumed to begin with the second unit of each product purchased.

MARGINAL UTILITY PER DOLLAR

Before applying the utility-maximizing rule to these data, we must put the marginal

utility information in columns 2(a) and 3(a) on a per-dollar-spent basis. Holly’s

choices are influenced not only by the extra utility that successive units of product

A will yield but also by how many dollars (and therefore how many units of alter-

native product B) she must give up to obtain those added units of A.

The rational consumer must compare the extra utility from each product with its

added cost (that is, its price). Suppose you prefer a pizza whose marginal utility is,

chapter seven • the theory of consumer choice 161

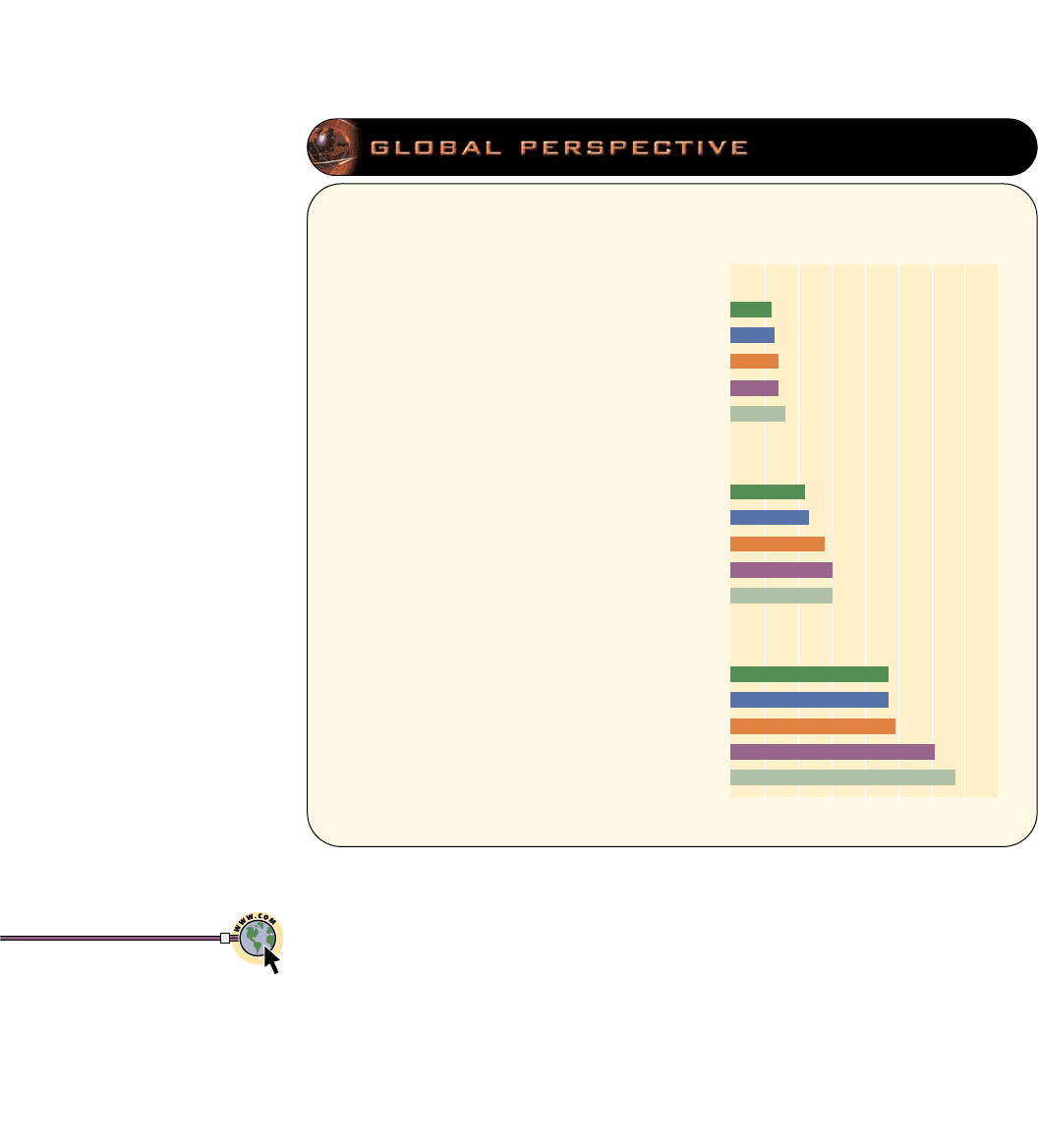

Shares of household

expenditures spent

on food, selected

nations

Consumer spending

patterns differ not only

individually but also

nationally. One striking

feature is that household

food expenditures as a

percentage of total

household spending

are much higher in low-

income countries than in

middle-income or high-

income countries.

7.1

High income

Japan

United States

Denmark

Canada

United Kingdom

Brazil

Middle income

Thailand

Russia

Mexico

Argentina

Food expenditures as a percentage

of total household expenditures

02040 80

Indonesia

Low income

Sierra Leone

Vietnam

Madagascar

Tanzania

60

Source: World Bank. Data are for 1998, <www.worldbank.com>.

<www.econtools.com/

jevons/java/choice/

Choice.html>

Ilustrates utility

maximization subject

to a budget constraint

say, 36 utils to a movie whose marginal utility is 24 utils. But if the pizza’s price is

$12 and the movie costs only $6, you would choose the movie rather than the pizza!

Why? Because the marginal utility per dollar spent would be 4 utils for the movie

(= 24 utils ÷ $6) compared to only 3 utils for the pizza (= 36 utils ÷ $12). You could

buy two movies for $12 and, assuming that the marginal utility of the second movie

is, say, 16 utils, your total utility would be 40 utils. Clearly, 40 units of satisfaction

from two movies are superior to 36 utils from the same $12 expenditure on one pizza.

To make the amounts of extra utility derived from differently priced goods comparable,

marginal utilities must be put on a per-dollar-spent basis. We do this in columns 2(b) and

3(b) by dividing the marginal utility data of columns 2(a) and 3(a) by the prices of

A and B, $1 and $2, respectively.

DECISION-MAKING PROCESS

In Table 7-1 we have Holly’s preferences on a unit basis, and a per-dollar basis, as

well as the price tags of A and B. With $10 to spend, in what order should Holly allo-

cate her dollars on units of A and B to achieve the highest degree of utility within

the $10 limit imposed by her income? What specific combination of A and B will she

have obtained at the time she uses up her $10?

Concentrating on columns 2(b) and 3(b) in Table 7-1, we find that Holly should first

spend $2 on the first unit of B, because its marginal utility per dollar of 12 utils is

higher than A’s 10 utils. Now Holly finds herself indifferent about whether she should

buy a second unit of B or the first unit of A because the marginal utility per dollar of

both is 10 utils. So she buys both of them. Holly now has one unit of A and two units

of B. Also, the last dollar she spent on each good yielded the same marginal utility per

dollar (10 utils), but this combination of A and B does not represent the maximum

amount of utility that Holly can obtain. It cost her only $5 [= (1 × $1) + (2 × $2)], so she

has $5 remaining, which she can spend to achieve a still higher level of total utility.

Examining columns 2(b) and 3(b) again, we find that Holly should spend the next

$2 on a third unit of B because marginal utility per dollar for the third unit of B is

162 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

TABLE 7-1 THE UTILITY-MAXIMIZING COMBINATION OF PRODUCTS

A AND B OBTAINABLE WITH AN INCOME OF $10*

(1) (2) (3)

Unit of product Product A: price = $1 Product B: price = $2

(a) (b) (a) (b)

Marginal utility, Marginal utility Marginal utility, Marginal utility

utils per dollar (MU/price) utils per dollar (MU/price)

First 10 10 24 12

Second 8 8

20 10

Third 7 7 18 9

Fourth 6 6 16 8

Fifth 5 5 12 6

Sixth 4 4 6 3

Seventh 3 3 4 2

*It is assumed in this table that the amount of marginal utility received from additional units of each of the two products is

independent of the quantity of the other product. For example, the marginal-utility schedule for product A is independent of the

amount of B obtained by the consumer.

nine compared with eight for the second unit of A. Now, with one unit of A and

three units of B, she is again indifferent between a second unit of A and a fourth unit

of B because both provide eight utils per dollar. So Holly purchases one more unit

of each. Now the last dollar spent on each product provides the same marginal util-

ity per dollar (eight utils), and Holly’s money income of $10 is exhausted.

The utility-maximizing combination of goods attainable by Holly is two units of A and

four of B. By summing marginal utility information from columns 2(a) and 3(a), we

find that Holly is obtaining 18 (= 10 + 8) utils of satisfaction from the two units of A

and 78 (= 24 + 20 + 18 + 16) utils of satisfaction from the four units of B. Her $10,

optimally spent, yields 96 (= 18 + 78) utils of satisfaction.

Table 7-2, which summarizes our step-by-step process for maximizing Holly’s

utility, merits careful study. Note that we have implicitly assumed that Holly spends

her entire income. She neither borrows nor saves. However, saving can be regarded

as a commodity that yields utility and be incorporated into our analysis. In fact, we

treat it that way in question 4 at the end of this chapter. (Key Question 4)

INFERIOR OPTIONS

Holly can obtain other combinations of A and B with $10, but none will yield as

great a total utility as do two units of A and four of B. As an example, she can obtain

four units of A and three of B for $10. However, this combination yields only 93 utils,

clearly inferior to the 96 utils provided by two units of A and four of B. Furthermore,

other combinations of A and B exist (such as four of A and five of B or one of A and

two of B) in which the marginal utility of the last dollar spent is the same for both

A and B. All such combinations are either unobtainable with Holly’s limited money

income (as four of A and five of B) or do not exhaust her money income (as one of

A and two of B) and, therefore, fail to yield the maximum utility attainable.

As an exercise, suppose Holly’s money income is $14 rather than $10. What is the

utility-maximizing combination of A and B? Are A and B normal or inferior goods?

Algebraic Restatement

Our allocation rule says that a consumer will maximize satisfaction by allocating

money income so that the last dollar spent on product A, the last on product B,

and so forth, yield equal amounts of additional, or marginal, utility. The marginal

chapter seven • the theory of consumer choice 163

TABLE 7-2 SEQUENCE OF PURCHASES TO ACHIEVE CONSUMER

EQUILIBRIUM, GIVEN THE DATA IN TABLE 7-1

Choice Marginal utility

number Potential choices per dollar Purchase decision Income remaining

1 First unit of A 10 First unit of B for $2 $8 = $10 – $2

First unit of B 12

2 First unit of A 10 First unit of A for $1 $5 = $8 – $3

Second unit of B 10 and second unit of B for $2

3 Second unit of A 8 Third unit of B for $2 $3 = $5 – $2

Third unit of B 9

4 Second unit of A 8 Second unit of A for $1 $0 = $3 – $3

Fourth unit of B 8 and fourth unit of B for $2

utility per dollar spent on A is indicated by MU of product A divided by the price

of A (column 2(b) in Table 7-1), and the marginal utility per dollar spent on B by MU

of product B divided by the price of B (column 3(b) in Table 7-1). Our utility-

maximizing rule merely requires that these ratios be equal. Algebraically,

=

Of course, the consumer must exhaust her available income. Table 7-1 shows us that

the combination of two units of A and four of B fulfills these conditions in that

=

and the consumer’s $10 income is spent.

If the equation is not fulfilled, then some reallocation of the consumer’s expen-

ditures between A and B (from the low to the high marginal-utility-per-dollar prod-

uct) will increase the consumer’s total utility. For example, if the consumer spent $10

on four units of A and three of B, we would find that

<

Here the last dollar spent on A provides only six utils of satisfaction, and the last

dollar spent on B provides nine (= 18 ÷ $2). So, the consumer can increase total sat-

isfaction by purchasing more of B and less of A. As dollars are reallocated from A to

B, the marginal utility per dollar of A will increase while the marginal utility per dol-

lar of B will decrease. At some new combination of A and B, the two will be equal,

and consumer equilibrium will be achieved. Here, that combination is two units of

A and four of B.

Once you understand the utility-maximizing rule, you can easily see why product

price and quantity demanded are inversely related. Recall that the basic determi-

nants of an individual’s demand for a specific product are (1) preferences or tastes,

(2) money income, and (3) the prices of other goods. The utility data in Table 7-1

reflect our consumer’s preferences. We continue to suppose that her money income

is $10. Concentrating on the construction of a simple demand curve for product B,

we assume that the price of A, representing other goods, is still $1.

Deriving the Demand Schedule and Curve

We can derive a single consumer’s demand schedule for product B by considering

alternative prices at which B might be sold and then determining the quantity the

consumer will purchase. We have already determined one such price–quantity

combination in the utility-maximizing example: given tastes, income, and prices of

other goods, our rational consumer will purchase four units of B at $2.

Now let’s assume the price of B falls to $1. The marginal-utility-per-dollar data

of column 3(b) in Table 7-1 will double because the price of B has been halved; the

new data for column 3(b) are identical to those in column 3(a), but the purchase of

two units of A and four of B is no longer an equilibrium combination. By applying

the same reasoning we used in the initial utility-maximizing example, we now find

MU of B: 18 utils

ᎏᎏ

Price of B: $2

MU of A: 6 utils

ᎏᎏ

Price of A: $1

16 utils

ᎏ

$2

8 utils

ᎏ

$1

MU of Product B

ᎏᎏ

Price of B

MU of Product A

ᎏᎏ

Price of A

164 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

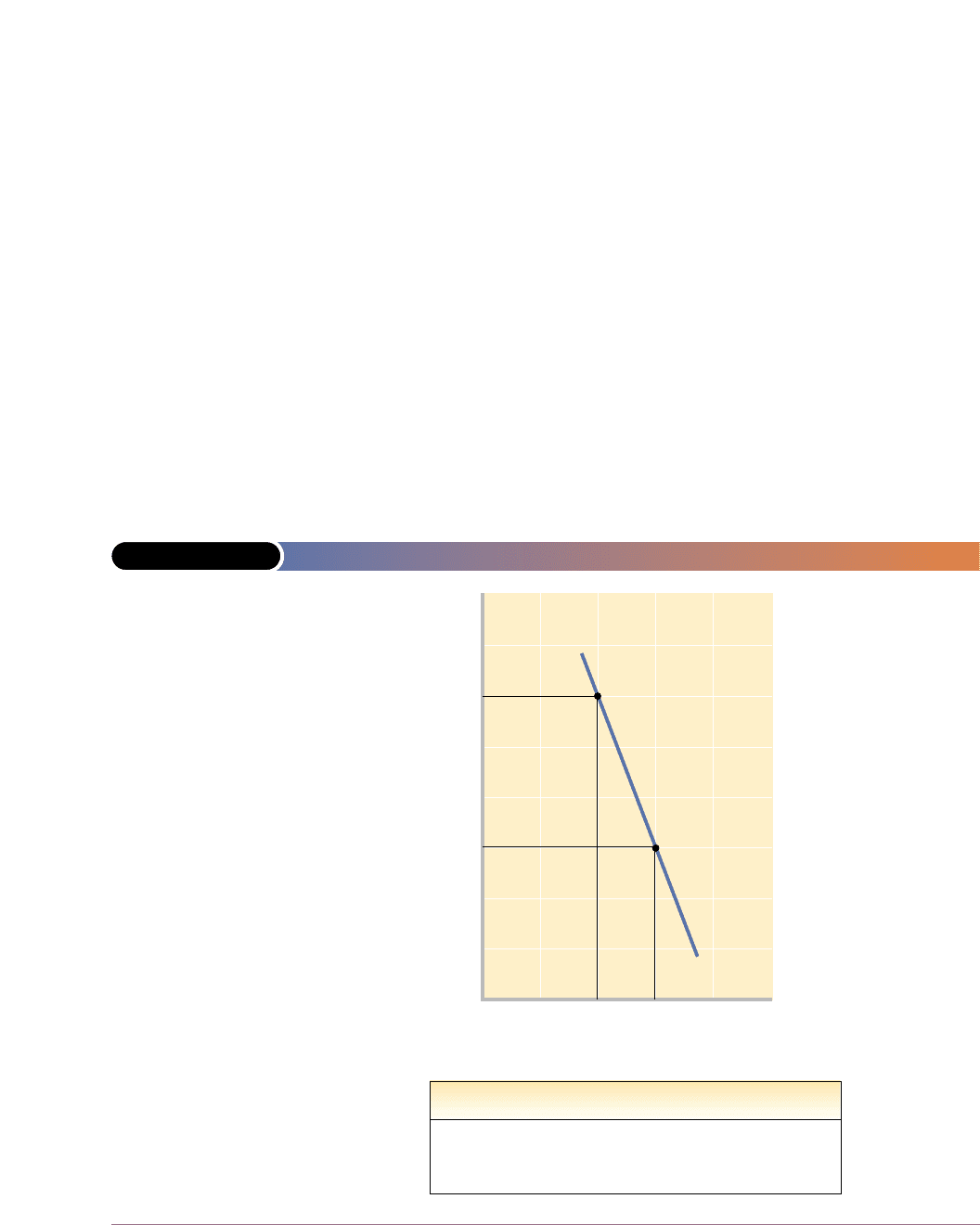

Utility Maximization and the Demand Curve

that Holly’s utility-maximizing combination is four units of A and six units of B. As

summarized in the table in Figure 7-2, Holly will purchase six units of B when the

price of B is $1. Using the data in this table, we can sketch the downward-sloping

demand curve D

B

shown in Figure 7-2. This exercise, then, clearly links the utility-

maximizing behaviour of a consumer and that person’s demand curve for a partic-

ular product.

Income and Substitution Effects Revisited

At the beginning of this chapter we mentioned that the law of demand can be

understood in terms of the substitution and income effects. Our analysis does not

let us sort out these two effects quantitatively. However, we can see through utility

maximization how each is involved in the increased purchase of product B when the

price of B falls.

To see the substitution effect, recall that before the price of B declined, Holly was

in equilibrium when purchasing two units of A and four units of B in that

MU

A

(8)/P

A

($1) = MU

B

(16)/P

B

($2). After B’s price falls from $2 to $1, we have

MU

A

(8)/P

A

($1) < MU

B

(16)/P

B

($1); more simply stated, the last dollar spent on B

chapter seven • the theory of consumer choice 165

FIGURE 7-2 DERIVING AN INDIVIDUAL DEMAND CURVE

Price per unit of B Quantity demanded

$2

1

4

6

$2

1

0

46

Quantity demanded of B

Price per unit of B

D

B

At a price of $2 for

product B, the con-

sumer represented

by the data in the

table maximizes utility

by purchasing four

units of product B.

The decline in the

price of product B

to $1 upsets the

consumer’s initial

utility-maximizing

equilibrium. The con-

sumer restores equi-

librium by purchasing

six rather than four

units of product B.

Thus, a simple

price–quantity sched-

ule emerges, which

locates two points on

a downward-sloping

demand curve.

now yields more utility (16 utils) than does the last dollar spent on A (8 utils). This

result indicates that a switching of purchases from A to B is needed to restore equi-

librium; that is, a substitution of the now cheaper B for A will occur when the price

of B drops.

What about the income effect? The assumed decline in the price of B from $2 to $1

increases Holly’s real income. Before the price decline, Holly was in equilibrium

when buying two units of A and four of B. At the lower $1 price for B, Holly would

have to spend only $6 rather than $10 on this same combination of goods. She has

$4 left over to spend on more of A, more of B, or more of both. In short, the price

decline of B has caused Holly’s real income to increase so that she can now obtain

larger amounts of A and B with the same $10 of money income. The portion of the

increase in her purchases of B due to this increase in real income is the income effect.

(Key Question 5)

Many real-world phenomena can be explained by applying the theory of consumer

behaviour.

The Compact Disc Takeover

Compact discs (CDs) made their debut in Canada in 1983. The CD revolutionized

the retail music industry, pushing the vinyl long-playing record (LP) to virtual

extinction. In 1983 fewer than one million CDs were sold in North America com-

pared with almost 210 million LPs. By 1999 some one billion CDs were sold, while

the sales of LPs plummeted to 2.9 million.

This swift turnabout resulted from both price and quality considerations.

Although the price of CDs has not declined significantly, the price of CD players has

nose-dived. Costing $1000 or more a decade ago, most players currently sell for less

than $150. Portable CD players are priced even lower. While CDs and LPs are sub-

stitute goods, CD players and CDs are complementary goods. The lower price for CD

players has expanded their sales and greatly increased the demand for CDs. CDs

hold much more music than LPs and provide a wider range of sound and greater

brilliance of musical tone than LPs.

In terms of our analysis, CD players and CDs have higher ratios of marginal util-

ity to price than do LP players and LPs. The vast majority of consumers have dis-

covered that they can enhance their total utility by substituting CDs for LPs.

166 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

● The theory of consumer behaviour assumes

that, with limited income and a set of product

prices, consumers make rational choices on the

basis of well-defined preferences.

● A consumer maximizes utility by allocating in-

come so that the marginal utility per dollar spent

is the same for every good purchased.

● We can derive a downward-sloping demand

curve by changing the price of one product in

the consumer-behaviour model and noting the

change in the utility-maximizing quantity of that

product demanded.

Applications and Extensions

The Diamond–Water Paradox

Early economists such as Adam Smith were puzzled by the fact that some essential

goods had much lower prices than some unimportant goods. Why would water,

essential to life, be priced below diamonds, which have much less usefulness? The

paradox is resolved when we acknowledge that water is in great supply relative to

demand and thus has a very low price per litre. Diamonds, in contrast, are rare and

are costly to mine, cut, and polish. Because their supply is small relative to demand,

their price is very high per caret.

The marginal utility of the last unit of water consumed is very low. The reason

follows from our utility-maximizing rule. Consumers (and producers) respond to

the very low price of water by using a great deal of it for generating electricity, irri-

gating crops, heating buildings, watering lawns, quenching thirst, and so on. Con-

sumption is expanded until marginal utility, which declines as more water is

consumed, equals its low price. Conversely, relatively few diamonds are purchased

because of their prohibitively high price, meaning that their marginal utility

remains high. In equilibrium

=

Although the marginal utility of the last unit of water consumed is low and the

marginal utility of the last diamond purchased is high, the total utility of water is

very high and the total utility of diamonds quite low. The total utility derived from

the consumption of water is large because of the enormous amounts of water con-

sumed. Total utility is the sum of the marginal utilities of all the litres of water con-

sumed, including the trillions of litres that have far higher marginal utilities than the

last unit consumed. In contrast, the total utility derived from diamonds is low since

their high price means that relatively few of them are bought. Thus the water–

diamond paradox is solved: water has much more total utility (roughly, usefulness)

than diamonds even though the price of diamonds greatly exceeds the price of

water. These relative prices relate to marginal utility, not total utility.

The Value of Time

The theory of consumer behaviour has been generalized to account for the eco-

nomic value of time. Both consumption and production take time. Time is a valu-

able economic commodity; by using an hour in productive work, a person can

earn $6, $10, $50, or more, depending on education and skills. By using that hour

for leisure or in consumption activities, the individual incurs the opportunity cost

of forgone income and sacrifices the $6, $10, or $50 that could have been earned

by working.

Imagine a self-employed consumer who is considering buying a round of golf on

the one hand, and a concert on the other. The market price of the golf game is $30

and that of the concert is $40, but the golf game takes more time than the concert.

Suppose this consumer spends four hours on the golf course but only two hours at

the concert. If the consumer’s time is worth $10 per hour as evidenced by the $10

wage obtained by working, then the full price of the golf game is $70 (the $30 mar-

ket price plus $40 worth of time). Similarly, the full price of the concert is $60 (the

$40 market price plus $20 worth of time). We find that, contrary to what market

prices alone indicate, the full price of the concert is really less than the full price of

the golf game.

MU of diamonds (high)

ᎏᎏᎏ

Price of diamonds (high)

MU of water (low)

ᎏᎏᎏ

Price of water (low)

chapter seven • the theory of consumer choice 167

<william-

king.www.drexel.edu/

top/prin/txt/MUch/

Eco412.html>

Adam Smith and the

diamond–water

paradox

168 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

If we now assume that the marginal utilities derived from successive golf games

and concerts are identical, traditional theory would indicate that our consumer

should consume more golf games than concerts because the market price of the for-

mer ($30) is lower than that of the latter ($40). When time is taken into account, the

situation is reversed, and golf games ($70) are more expensive than concerts ($60).

So, it is rational for this person to consume more concerts than golf games.

By accounting for time, we can explain certain observable phenomena that tra-

ditional theory does not explain. It may be rational for the unskilled worker or

retiree whose time has little market value to ride a bus from Edmonton to Saska-

toon, but the corporate executive, whose time is very valuable, will find it cheaper

to fly, even though bus fare is only a fraction of plane fare. It is sensible for the

retiree, living on a modest income and having ample time, to spend many hours

shopping for bargains at the mall or taking long trips in a motor home. It is equally

intelligent for the highly paid physician, working 55 hours per week, to buy a new

personal computer over the Internet and take short vacations at expensive resorts.

People in other nations often feel affluent Canadians are wasteful of food and

other material goods but overly economical in their use of time. Canadians who visit

developing countries often feel that time is used casually or squandered, while

material goods are very highly prized and carefully used. These differences are not

a paradox or a case of radically different temperaments; the differences are prima-

rily a rational reflection that the high productivity of labour in an industrially

advanced society gives time a high market value, whereas the opposite is true in a

low-income, developing country.

Cash and Noncash Gifts

Marginal utility analysis also helps us understand why people generally prefer cash

gifts to noncash gifts costing the same amount. The reason is simply that the non-

cash gifts may not match the recipient’s preferences and thus may not add as much

as cash to total utility—consumers know their own preferences better than the gift

giver does and the cash gift provides more choices.

Look back at Table 7-1. Suppose Holly has zero earned income but is given the

choice of a $2 cash gift or a noncash gift of two units of A. Because two units of A

can be bought with $2, these two gifts are of equal monetary value, but by spend-

ing the $2 cash gift on the first unit of B, Holly could obtain 24 utils. The noncash

gift of the first two units of A would yield only 18 (= 10 + 8) units of utility; the non-

cash gifts yields less utility to the beneficiary than the cash gift.

Since giving of noncash gifts is common, considerable value of those gifts is

potentially lost because they do not match their recipients’ tastes. For example, Aunt

Flo may have paid $15 for the Celine Dion CD she gave you for your birthday, but

you would pay only $7.50 for it. Thus, a $7.50, or 50 percent, value loss is involved.

Multiplied by billions spent on gifts each year, the potential loss of value is large.

Some of that loss is avoided by the creative ways individuals handle the problem.

For example, newlyweds set up gift registries for their weddings to help match their

wants to the noncash gifts received. Also, people obtain cash refunds or exchanges

for gifts, so they can buy goods that provide more utility. And people have even

been known to recycle gifts by giving them to someone else at a later time. All three

actions support the proposition that individuals take actions to maximize their

total utility.

chapter seven • the theory of consumer choice 169

Through extension, the theory

of rational consumer behaviour

provides some useful insights on

criminal behaviour. Both the law-

ful consumer and the criminal try

to maximize their total utility (or

net benefit). For example, you

can remove a textbook from the

campus bookstore either by pur-

chasing it or stealing it. If you buy

the book, your action is legal; you

have fully compensated the book-

store for the product. (The book-

store would rather have your

money than the book.) If you

steal the book, you have broken

the law. Theft is outlawed be-

cause it imposes uncompensated

costs on others. In this case, your

action reduces the bookstore’s

revenue and profit and also may

impose costs on other buyers

who now must pay higher prices

for their textbooks.

Why might someone engage

in criminal activity such as steal-

ing? Just like the consumer who

compares the marginal utility of

a good with its price, the poten-

tial criminal compares the mar-

ginal benefit from an action with

the price or cost. If the marginal

benefit (to the criminal) exceeds

the price or marginal cost (also

to the criminal), the individual

undertakes the criminal activity.

Most people, however, do not

engage in theft, burglary, or

fraud. Why not? The answer is

that they perceive the personal

price of engaging in these illegal

activities to be too high relative

to the marginal benefit. That price

or marginal cost to the potential

criminal has several facets. First,

there are the guilt costs, which

for many people are substantial.

Such individuals would not steal

from others even if there were no

penalties for doing so; their moral

sense of right and wrong would

entail too great a guilt cost rela-

tive to the benefit from the stolen

good. Other types of costs in-

clude the direct costs of the crim-

inal activity (supplies and tools)

and the forgone income from le-

gitimate activities (the opportu-

nity cost to the criminal).

Unfortunately, guilt costs, di-

rect costs, and forgone income

are not sufficient to deter some

people from stealing. So society

imposes other costs, mainly fines

and imprisonment, on lawbreak-

ers. The potential of being fined

increases the marginal cost to the

criminal. The potential of being

imprisoned boosts marginal cost

still further. Most people highly

value their personal freedom and

lose considerable legitimate earn-

ings while incarcerated.

Given these types of costs, the

potential criminal estimates the

marginal cost and benefit of com-

mitting the crime. As a simple ex-

ample, suppose that the direct

cost and opportunity cost of steal-

ing an $80 textbook are both zero.

The probability of getting caught

is 10 percent, and, if appre-

hended, there will be a $500 fine.

The potential criminal will esti-

mate the marginal cost of stealing

the book as $50 (= $500 fine × .10

chance of apprehension). Some-

one who has guilt costs of zero

will choose to steal the book be-

cause the marginal benefit of $80

will exceed the marginal cost of

$50. In contrast, someone having

a guilt cost of, say, $40, will not

steal the book. The marginal ben-

efit of $80 will not be as great as

the marginal cost of $90 (= $50 of

penalty cost + $40 of guilt cost).

This perspective on illegal be-

haviour has some interesting

implications. For example, other

things equal, crime will rise

(more of it will be bought) when

its price falls. This explains, for

instance, why some people who

do not steal from stores under

normal circumstances partici-

pate in looting stores during

riots, when the marginal cost

of being apprehended declines

substantially.

Another implication is that

society can reduce unlawful be-

haviour by increasing the price

of crime. It can nourish and in-

crease guilt costs through fam-

ily, educational, and religious ef-

forts. It can increase the direct

costs of crime by using more

sophisticated security systems

(locks, alarms, video surveil-

lance) so that criminals will have

to buy and use more sophisti-

cated tools. It can undertake ed-

ucation and training initiatives

to enhance the legitimate earn-

ings of people who might other-

wise engage in illegal activity.

It can increase policing to raise

the probability of being appre-

hended for crime, and it can im-

pose greater penalties for those

who are caught and convicted.

CRIMINAL BEHAVIOUR

Although economic analysis is not particularly relevant in

explaining some crimes of passions and violence (for example,

murder and rape), it does provide interesting insights on

such property crimes as robbery, burglary, and auto theft.