McConnell Campbell R., Brue Stanley L., Barbiero Thomas P. Microeconomics. Ninth Edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

produce its Windows program only once. Then, at very low marginal cost, Microsoft

delivers its program by disk to millions of consumers. The same is true for Internet

service providers, music producers, and wireless communication firms. Because

marginal costs are so low, the average total cost of output declines as more cus-

tomers are added.

Network effects are increases in the value of a product to each user, including exist-

ing users, as the total number of users rises. Computer software, cell phones, pagers,

palm computers, and other products related to the Internet are good examples. When

others have Internet service and devices to access it, you can conveniently send e-mail

messages to them. When they have similar software, documents, spreadsheets, and

photos can be attached to the e-mail message. The benefits of the product to each per-

son are magnified the larger the number of people connected to the system.

Such network effects may drive a market toward monopoly because consumers

tend to choose standard products that everyone else is using. The focused demand

for these products permits their producers to grow rapidly and thus achieve

economies of scale. Smaller firms, which have the higher-cost right products or the

wrong products get acquired or go out of business.

Economists generally agree that some new information firms have not yet

exhausted their economies of scale, but, most economists question whether such

firms are truly natural monopolies. Most firms eventually achieve their minimum

efficient scale at less that the full size of the market, and, even if natural monopoly

develops, it’s unlikely that the monopolist will pass cost reductions along to con-

sumers as price reductions. So, with perhaps a handful of exceptions, economies of

scale do not change the general conclusion that monopolies yield less efficiency than

more competitive industries.

X-INEFFICIENCY

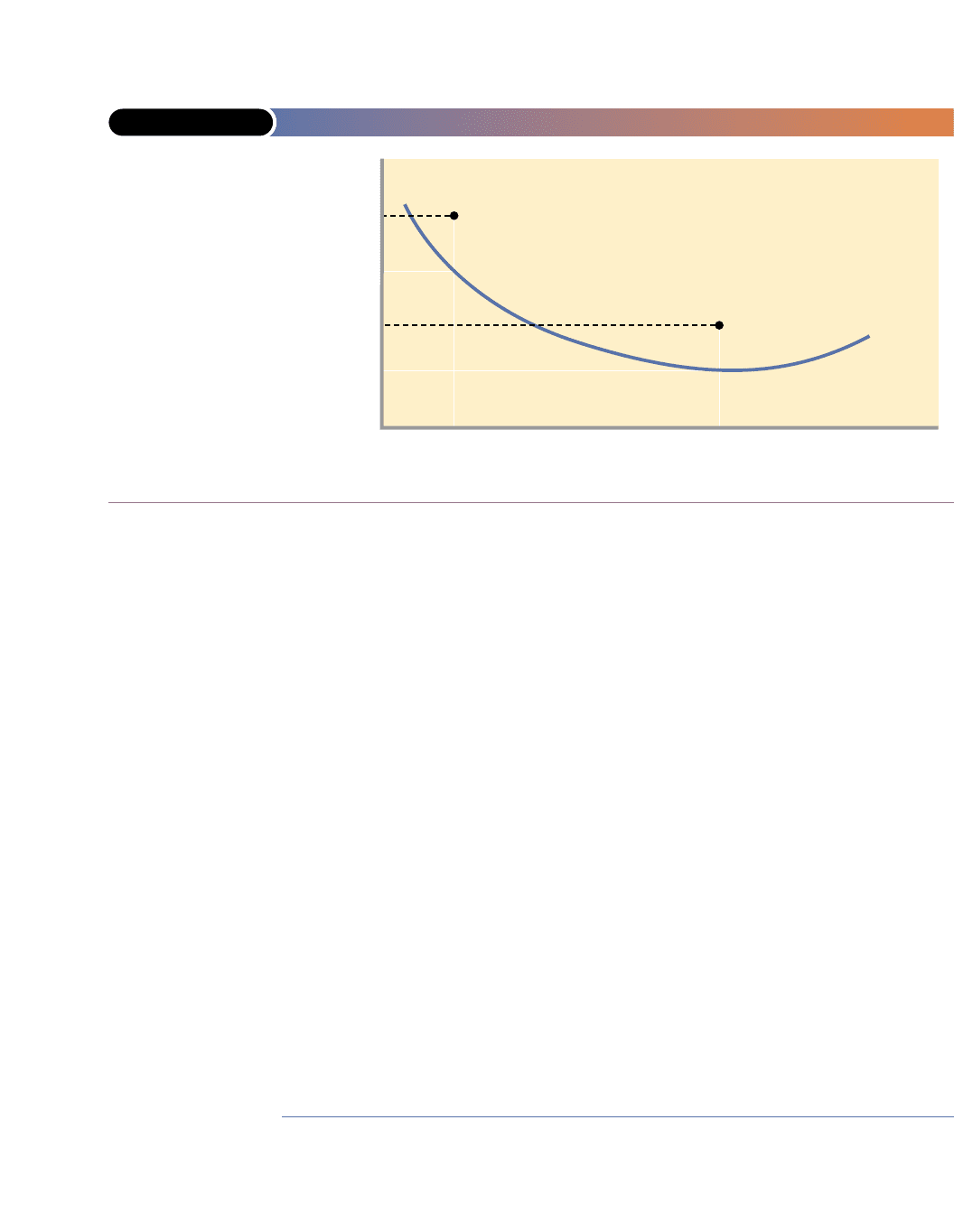

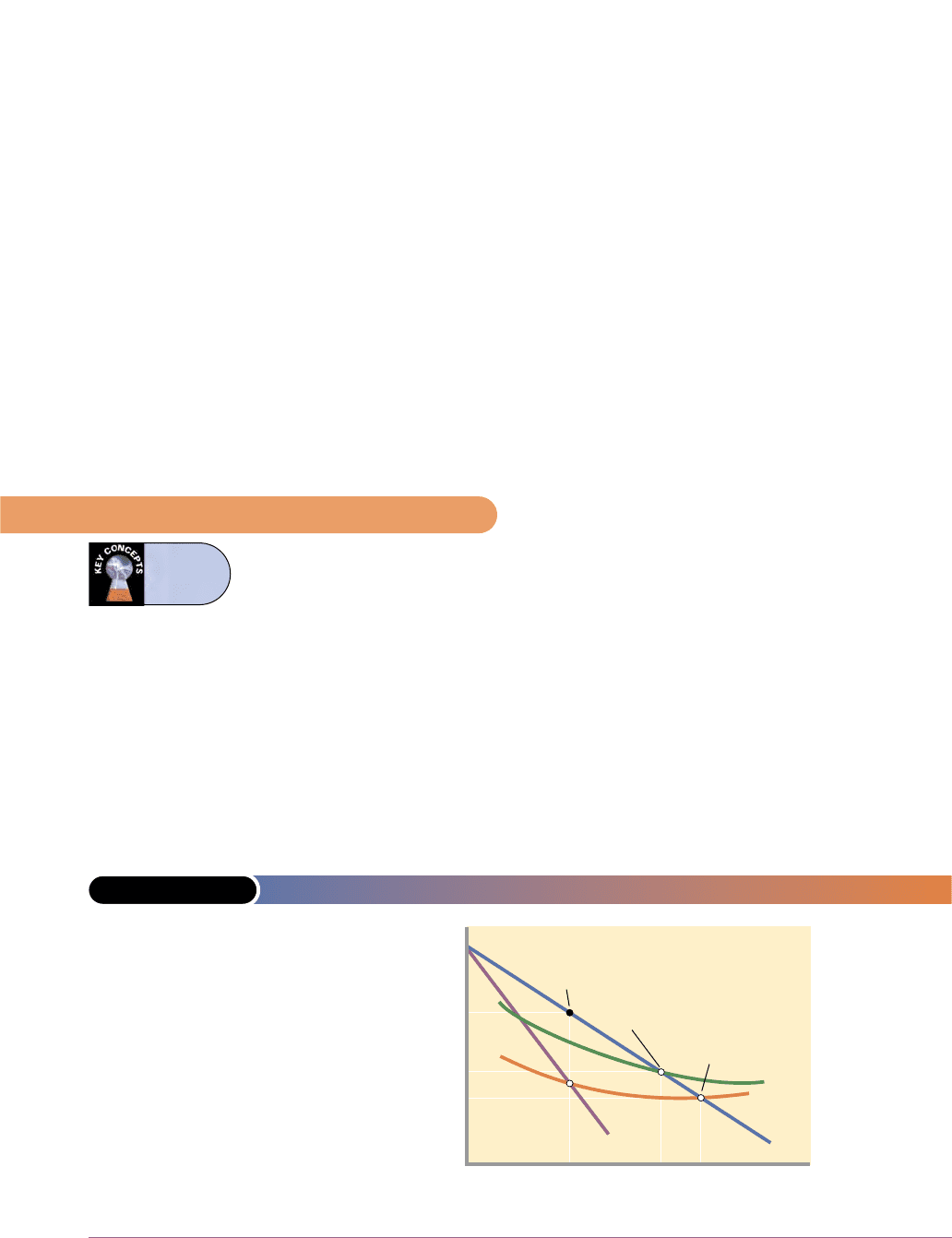

In constructing all the average-total-cost curves used in this book, we have assumed

that the firm uses the most efficient technology. In other words, it uses the technol-

ogy that permits it to achieve the lowest average total cost of whatever level of out-

put it chooses to produce. X-inefficiency occurs when a firm’s actual cost of

producing any output is greater than the lowest possible cost of producing it. In Fig-

ure 10-7 X-inefficiency is represented by operation at points X and X⬘ above the

lowest-cost ATC curve. At these points, per-unit costs are ATC

x

(as opposed to ATC

1

)

for output Q

1

and ATC

x⬘

(as opposed to ATC

2

) for output Q

2

. Any point above the

average-total-cost curve in Figure 10-7 is possible but reflects inefficiency or bad

management by the firm.

Why is X-inefficiency allowed to occur if it reduces profits? The answer is that

managers may have goals such as corporate growth, an easier work life, avoidance

of business risk, or giving jobs to incompetent relatives that conflict with cost min-

imization. Or X-inefficiency may arise because a firm’s workers are poorly moti-

vated or ineffectively supervised. Or a firm may simply become lethargic and inert,

relying on rules of thumb in decision making as opposed to relevant calculations of

costs and revenues.

For our purposes the relevant question is whether monopolistic firms tend more

toward X-inefficiency than competitive producers do. There is evidence that they

do. Firms in competitive industries are continually under pressure from rivals, forc-

ing them to be internally efficient to survive. But monopolists are sheltered from

such competitive forces by entry barriers, and that lack of pressure may lead to

X-inefficiency.

260 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

network

effects

Increases in the

value of a product

to each user, includ-

ing existing ones,

as the total number

of users rises.

x-inefficiency

Failure to produce

any specific output

at the lowest

average (and total)

cost possible.

<www.maths.tcd.ie/

pub/econrev/ser/html/

morton.html>

Monopoly and

x-efficiency

There is no indisputable evidence of X-inefficiency, but what evidence we have

suggests that it increases as the competition decreases. A reasonable estimate is that X-

inefficiency may be 10 percent or more of costs for monopolists but only 5 percent for

an average oligopolistic industry in which the four largest firms produce 60 percent of

total output.

1

In the words of one authority: “The evidence is fragmentary, but it points

in the same direction. X-inefficiency exists, and it is more apt to be reduced when com-

petitive pressures are strong than when firms enjoy insulated market positions.”

2

RENT-SEEKING EXPENDITURES

Rent-seeking behaviour is an attempt to transfer income or wealth to a particular

firm or resource supplier at someone else’s, or even society’s, expense. We have seen

that a monopolist can obtain an economic profit even in the long run. Therefore, it

is no surprise that a firm may go to great expense to acquire or maintain a monop-

oly granted by government through legislation or an exclusive licence. Such rent-

seeking expenditures add nothing to the firm’s output, but they clearly increase its

costs. They imply that monopoly involves higher costs and less efficiency than sug-

gested in Figure 10-6(b).

TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCE

In the very long run, firms can reduce their costs through the discovery and imple-

mentation of new technology. If monopolists are more likely than competitive pro-

ducers to develop more efficient production techniques over time, then the

inefficiency of monopoly might be overstated. Since research and development

(R&D) is the topic of Chapter 12, we will provide only a brief assessment here.

chapter ten • pure monopoly 261

FIGURE 10-7 X-INEFFICIENCY

X

X

′

ATC

1

ATC

X

ATC

2

′

ATC

X

Q

1

Q

2

0

Average total costs

Average

total cost

Quantity

The average-total-

cost curve (ATC) is

assumed to reflect

the minimum cost

of producing each

particular unit of

output. Any point

above this lowest-

cost ATC curve, such

as X or X⬘, implies X-

inefficiency: opera-

tion at greater than

lowest cost for a par-

ticular level of output.

1

William G. Shepherd, The Economics of Industrial Organization, 4th ed. (Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice-Hall, 1997), p. 107.

2

F. M. Scherer and David Ross, Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance, 3rd ed.

(Chicago: Rand McNally College Publishing, 1990), p. 672.

rent-seeking

behaviour

The actions by

persons, firms, or

unions to gain spe-

cial benefits from

government at tax-

payers’ or someone

else’s expense.

The general view of economists is that a pure monopolist will not be technolog-

ically progressive. Although its economic profit provides ample means to finance

R&D, it has little incentive to implement new techniques (or products). The absence

of competitors means that no external pressure exists for technological advance in

a monopolized market. Because of its sheltered market position, the pure monopo-

list can afford to be inefficient and lethargic; there simply is no penalty for being so.

One caveat: Research and technological advance may be one of the monopolist’s

barriers to entry. Thus, the monopolist may continue to seek technological advance

to avoid falling prey to new rivals. In this case technological advance is essential to

the maintenance of monopoly, but it is potential competition, not the monopoly

market structure, that is driving the technological advance. By assumption, no such

competition exists in the pure monopoly model; entry is completely blocked.

Assessment and Policy Options

Monopoly is a legitimate concern to an economy. Monopolists can charge higher-

than-competitive prices that result in an underallocation of resources to the monop-

olized product. Monopolists can stifle innovation, engage in rent-seeking behaviour,

and foster X-inefficiency. Even when their costs are low because of economies of scale,

monopolists make no guarantee that the price they charge will reflect those low costs.

The cost savings may simply accrue to the monopoly as greater economic profit.

Fortunately, however, monopoly is not widespread in the economy. Barriers to

entry are seldom completely successful. Although research and technological

advance may strengthen the market position of a monopoly, technology may also

undermine monopoly power. Over time, the creation of new technologies may work

to destroy monopoly positions. For example, the development of courier delivery, fax

machines, and e-mail has eroded the monopoly power of Canada Post Corporation.

Cable television monopolies are now challenged by satellite TV and by new tech-

nologies that permit the transmission of audio and visual signals over the Internet.

Similarly, patents eventually expire and even before they do, the development of

new and distinct substitutable products often circumvents existing patent advan-

tages. New sources of monopolized resources sometimes are found, and competi-

tion from foreign firms may emerge. Finally, if a monopoly is sufficiently fearful of

future competition from new products, it may keep its prices relatively low to dis-

courage rivals from developing such products. If so, consumers may pay nearly

competitive prices even though present competition is lacking.

So what should government do about monopoly when it arises in the real world?

Economists agree that government needs to look carefully at monopoly on a case-

by-case basis. Three general policy options are available:

1. If the monopoly is achieved and sustained through anticompetitive actions, creates

substantial economic inefficiency, and appears to be long lasting, the government

can file charges against the monopoly under Canada’a anti-combines laws. If

found guilty of monopoly abuse, the firm can either be expressly prohibited from

engaging in certain business activities or broken into two or more competing firms.

2. If the monopoly is a natural monopoly, society can allow it to continue expand-

ing. If no competition emerges from new products, government may then decide

to regulate its prices and operations.

3. If the monopoly appears to be unsustainable over a long period, say, because of

emerging new technology, society can simply choose to ignore it.

262 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

We have assumed in this chapter that the monopolist charges a single price to all

buyers. But under certain conditions the monopolist can increase its profit by charg-

ing different prices to different buyers. In so doing, the monopolist is engaging in

price discrimination, the practice of selling a specific product at more than one

price when the price differences are not justified by cost differences.

Conditions

The opportunity to engage in price discrimination is not readily available to all sell-

ers. Price discrimination is possible when the following conditions are realized:

● Monopoly power The seller must be a monopolist or, at least, possess some

degree of monopoly power, that is, some ability to control output and price.

● Market segregation The seller must be able to segregate buyers into distinct

classes, each of which has a different willingness or ability to pay for the prod-

uct. This separation of buyers is usually based on different elasticities of

demand, as the examples that follow will make clear.

● No resale The original purchaser cannot resell the product or service. If buy-

ers in the low-price segment of the market could easily resell in the high-price

segment, the monopolist’s price-discrimination strategy would create compe-

tition in the high-price segment. This competition would reduce the price in

the high-price segment and undermine the monopolist’s price-discrimination

policy. This condition suggests that service industries such as the transporta-

tion industry or legal and medical services, where resale is impossible, are

candidates for price discrimination.

Examples of Price Discrimination

Price discrimination is widely practised in the Canadian economy. For example, air-

lines charge high fares to travelling executives, whose demand for travel is inelastic,

and offer lower fares such as “family rates” and “14-day advance purchase fares”

to attract vacationers and others whose demands are more elastic.

chapter ten • pure monopoly 263

● The monopolist maximizes profit (or minimizes

loss) at the output where MR = MC and charges

the price that corresponds to that output on its

demand curve.

● The monopolist has no supply curve, since any

of several prices can be associated with a spe-

cific quantity of output supplied.

● Assuming identical costs, a monopolist will be

less efficient than a purely competitive industry

because the monopolist produces less output

and charges a higher price.

● The inefficiencies of monopoly may be offset or

lessened by economies of scale and, less likely,

by technological progress, but may be intensi-

fied by the presence of X-inefficiency and rent-

seeking expenditures.

Price Discrimination

price dis-

crimination

The selling of a

product to different

buyers at different

prices when the

price differences are

not justified by dif-

ferences in cost.

Electric utilities frequently segment their markets by end uses, such as lighting

and heating. The absence of reasonable lighting substitutes means that the demand

for electricity for illumination is inelastic and that the price per kilowatt-hour for

such use is high. But the availability of natural gas and petroleum for heating makes

the demand for electricity for this purpose less inelastic and the price lower.

Movie theatres and golf courses vary their charges on the basis of time (higher

rates in the evening and on weekends when demand is strong) and age (ability to

pay). Railroads vary the rate charged per tonne-kilometre of freight according to the

market value of the product being shipped. The shipper of 10 tonnes of television sets

or costume jewellery is charged more than the shipper of 10 tonnes of gravel or coal.

The issuance of discount coupons, redeemable at purchase, is a form of price dis-

crimination. It permits firms to give price discounts to their most price-sensitive cus-

tomers who have elastic demand. Less price-sensitive consumers who have less

elastic demand are not as likely to undertake the clipping and redeeming of

coupons. The firm thus makes a larger profit than if it had used a single-price, no-

coupon strategy.

Finally, price discrimination often occurs in international trade. A Russian alu-

minum producer, for example, might sell aluminum for less in Canada than in Rus-

sia. In Canada, this seller faces an elastic demand because several substitute

suppliers are available. But in Russia, where the manufacturer dominates the mar-

ket and trade barriers impede imports, consumers have fewer choices and thus

demand is less elastic.

Consequences of Price Discrimination

As you will see shortly, a monopolist can increase its profit by practising price dis-

crimination. At the same time, perfect price discrimination results in more output than

would be purchased at a single monopoly price. Such price discrimination occurs

when the monopolist charges each customer the price that he or she would be will-

ing to pay rather than forgo the product.

MORE PROFIT

Let’s again consider our monopolist’s downsloping demand curve in Figure 10-4,

this time to see why price discrimination can yield additional profit. In that figure

we saw that the profit-maximizing single price is P

m

= $122. However, the segment

of the demand curve above the economic profit area (in grey) reveals that some buy-

ers are willing to pay more than $122 rather than forgo the product.

If the monopolist can identify those buyers, segregate them, and charge the max-

imum price each would be willing to pay, total revenue and economic profit would

increase. Observe from columns 1 and 2 in Table 10-1 that buyers of the first four

units of output would be willing to pay $162, $152, $142, and $132, respectively, for

those units. If the seller could practise perfect price discrimination by charging the

maximum price for each unit, total revenue would increase from $610 (= $122 × 5)

to $710 (= $122 + $132 + $142 + $152 + $162) and profit would increase from $140

(= $610 – $470) to $240 (= $710 – $470).

MORE PRODUCTION

Other things being equal, the monopolist practising perfect price discrimination

will produce a larger output than the monopolist that does not. When the non-

discriminating monopolist lowers its price to sell additional output, the lower price

264 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

<classes.aces.uiuc.edu/

ACE325/prdisc.html>

Price discrimination

not only applies to the additional output but also to all the prior units of output. So

the single-price monopolist’s marginal revenue falls more rapidly than price and,

graphically, its marginal-revenue curve lies below its demand curve. The decline of

marginal revenue is a disincentive to increased production.

When a discriminating monopolist lowers its price, the reduced price applies

only to the additional units sold and not to the prior units. Thus, marginal revenue

equals price for each unit of output and the firm’s marginal revenue curve and

demand curve coincide. The disincentive to increased production is removed.

We can show the outcome through Table 10-1. Because marginal revenue and

price are equal, the discriminating monopolist finds it profitable to produce seven

units, not five units, of output. The additional revenue from the sixth and seventh

units is $214 (= $112 + $102). Thus, total revenue for seven units is $924 (= $710 +

$214). Since total cost for seven units is $640, profit is $284.

Ironically, although perfect price discrimination results in higher monopoly profit

than that achieved by a nondiscriminating monopolist, it also results in greater out-

put and thus less allocative inefficiency. In our example, the output level of seven

units matches the output that would have occurred in pure competition; that is,

allocative efficiency (P = MC) is achieved.

GRAPHICAL PORTRAYAL

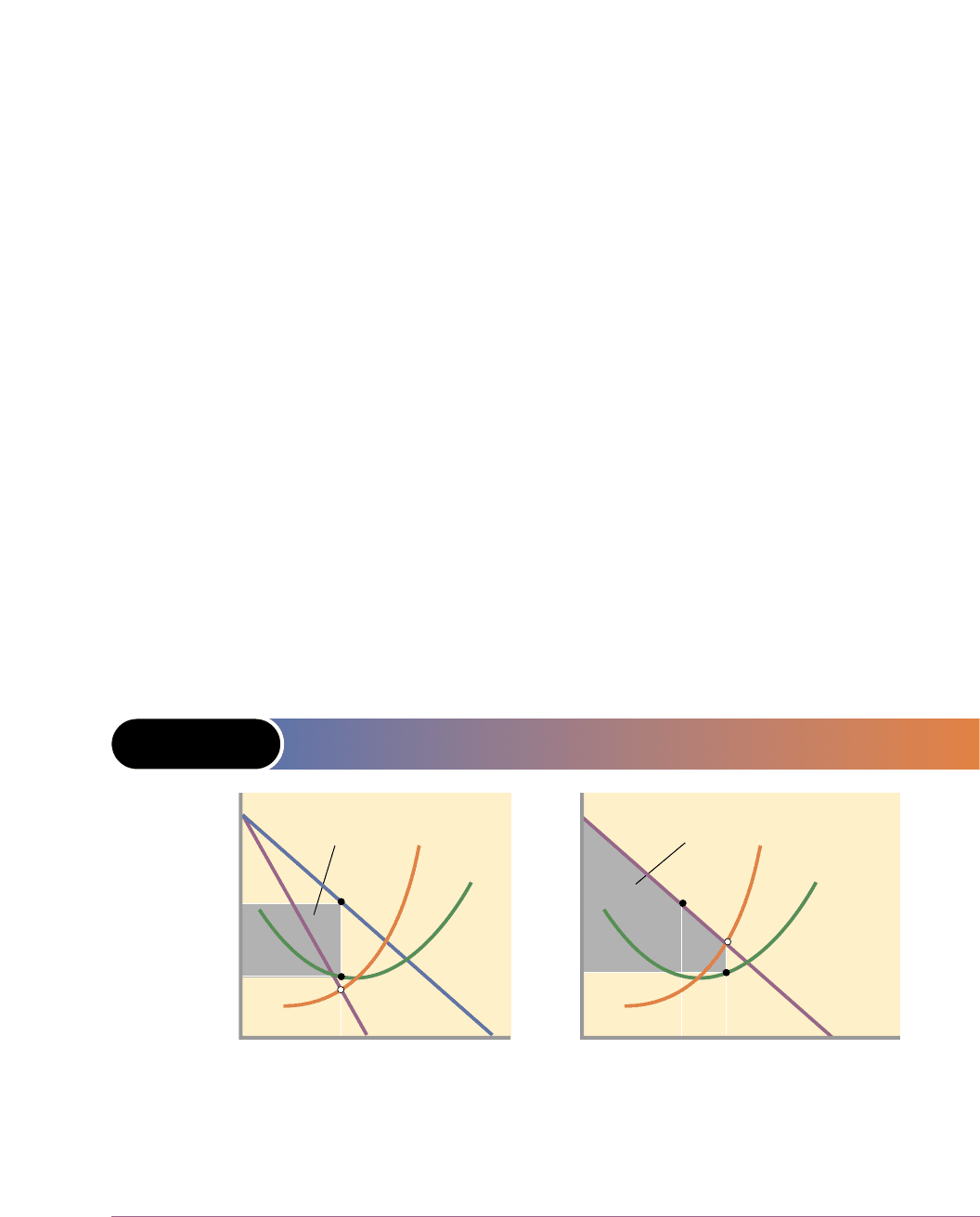

Figure 10-8 shows the effects of price discrimination graphically. Figure 10-8(a)

merely reproduces Figure 10-4 in a generalized form to show the position of a

nondiscriminating monopolist as a benchmark. The nondiscriminating monopolist

produces output Q

1

(where MR = MC) and charges price P

1

. Total revenue is area

0bce and economic profit is area abcd.

chapter ten • pure monopoly 265

FIGURE 10-8 SINGLE-PRICE VERSUS PERFECTLY DISCRIMINATING

MONOPOLY PRICING

Q

1

0

f

b

A

1

A

2

P

1

a

c

d

Price and costs

(a) Single-price monopolist

Quantity

Economic

profit

Q

1

Q

2

0

f

c

g

j

Price and costs

(b) Perfectly discriminating monopolist

Quantity

Economic

profit

e

h

k

D

MR

ATC

MC

ATC

MC

D

= MR

Panel (a): The single-price monopolist produces output Q

1

at which MR = MC, charges price P

1

for all units, incurs an average

total cost of A

1

, and realizes an economic profit represented by area abcd. Panel (b): The perfectly discriminating monopolist

has D = MR and, as a result, produces output Q

2

(where MR = MC). It then charges the maximum price for each unit of output,

incurs average total cost A

2

, and realizes an economic profit represented by area hfgj.

The monopolist in Figure 10-8(b) engages in perfect price discrimination, charg-

ing each buyer the highest price he or she is willing to pay. Starting at the very first

unit, each additional unit is sold for the price indicated by the corresponding point

on the demand curve. This monopolist’s demand and marginal-revenue curves

coincide, because the monopolist does not cut price on preceding units to sell more

output. Thus, the most profitable output is Q

2

(where MR = MC), which is greater

than Q

1

. Total revenue is area 0fgk and total cost is area 0hjk. The economic profit of

hfgj for the discriminating monopolist is clearly larger than the profit of abcd for the

single-price monopolist.

The impact of price discrimination on consumers is mixed. Those buying each unit

up to Q

1

will pay more than the nondiscriminatory price of P

1

. But those additional

consumers brought into the market by discrimination will pay less than P

1

. Specifi-

cally, they will pay the various prices shown on segment cg of the D = MR curve.

Overall, then, as compared with uniform pricing, perfect price discrimination

results in greater profit, greater output, and higher prices for many consumers but

lower prices for those purchasing the extra output. (Key Question 6)

Natural monopolies traditionally have been subject to rate regulation (price regula-

tion), although the recent trend has been to deregulate those parts of the industries

where competition seems possible. Provincial or municipal regulatory commissions

still regulate the prices that municipal natural gas distributors, regional telephone

companies, and municipal electricity suppliers can charge. But long-distance tele-

phone, natural gas at the well-head, wireless communications, cable television, and

long-distance electricity transmission have been, to one degree or another, deregu-

lated over the past several decades, and competition among local telephone, elec-

tricity, and natural gas providers is now beginning.

Let’s consider the regulation of a local natural monopoly, for example, a natural gas

distributor. Figure 10-9 shows the demand and the long-run costs curves facing our

firm. Because of extensive economies of scale, the demand curve cuts the natural

monopolist’s long-run average-total-cost curve at a point where that curve is still

266 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

FIGURE 10-9 REGULATED MONOPOLY

f

a

b

r

P

m

P

f

P

r

Q

m

Q

f

Q

r

0

Monopoly

price

Fair-return

price

Socially

optimal

price

Quantity

Price and costs (dollars)

ATC

MC

D

MR

The socially optimal

price P

r

, found where

D and MC intersect,

will result in an effi-

cient allocation of

resources but may

entail losses to the

monopoly. The fair-

return price P

f

will

allow the monopolist

to break even but will

not fully correct the

underallocation of

resources.

Regulated Monopoly

The Role of

Governments

falling. It would be inefficient to have several firms in this industry because each

would produce a much smaller output, operating well to the left on the long-run

average-total-cost curve. In short, each firms’ lowest average total cost would be sub-

stantially higher than that of a single firm. So, this circumstance requires a single seller.

We know by application of the MR = MC rule that Q

m

and P

m

are the profit-

maximizing output and price that an unregulated monopolist would choose.

Because price exceeds average total cost at output Q

m

, the monopolist enjoys a sub-

stantial economic profit. Furthermore, price exceeds marginal cost, indicating an

underallocation of resources to this product or service. Can government regulation

bring about better results from society’s point of view?

Socially Optimal Price: P = MC

If the objective of a regulatory commission is to achieve allocative efficiency, it

should attempt to establish a legal (ceiling) price for the monopolist that is equal to

marginal cost. Remembering that each point on the market demand curve desig-

nates a price–quantity combination, and noting that the marginal-cost curve cuts the

demand curve only at point r, we see that P

r

is the only price on the demand curve

equal to marginal cost. The maximum or ceiling price effectively causes the monop-

olist’s demand curve to become horizontal (indicating perfectly elastic demand)

from zero out to point r, where the regulated price ceases to be effective. Also, out

to point r we have MR = P

r

.

Confronted with the legal price P

r

, the monopolist will maximize profit or mini-

mize loss by producing Q

r

units of output, because at this output MR (= P

r

) = MC.

By making it illegal to charge more than P

r

per unit, the regulatory agency has

removed the monopolist’s incentive to restrict output to Q

m

to obtain a higher price

and greater profit.

In short, the regulatory commission can simulate the allocative forces of pure com-

petition by imposing the legal price P

r

and letting the monopolist choose its profit-

maximizing or loss-minimizing output. Production takes place where P

r

= MC, and

this equality indicates an efficient allocation of resources to this product or service.

The price that achieves allocative efficiency is called the socially optimal price.

Fair-Return Price: P = ATC

It is possible for the socially optimal price, P

r

, that equals marginal cost to be so low

that average total costs are not covered, as is the case in Figure 10-9. The result is a

loss for the firm. The reason lies in the basic character of our firm. Because it is

required to meet the heaviest peak demands (both daily and seasonally) for natural

gas, it has substantial excess production capacity when demand is relatively “nor-

mal.” Its high level of investment in production facilities and economies of scale

mean that its average total cost is likely to be greater than its marginal cost over a

very wide range of outputs. In particular, as in Figure 10-9, average total cost is likely

to be greater than the price P

r

at the intersection of the demand curve and marginal-

cost curve. Therefore, forcing the socially optimal price P

r

on the regulated monop-

olist would result in short-run losses and long-run bankruptcy for the utility.

What to do? One option is to provide a public subsidy to cover the loss that

marginal-cost pricing would entail. Another possibility is to condone price discrim-

ination and hope that the additional revenue gained will permit the firm to cover costs.

In practice, regulatory commissions have pursued a third option: They modify

the objective of allocative efficiency and P = MC pricing. Most regulatory agencies

in Canada establish a fair-return price.

chapter ten • pure monopoly 267

socially

optimal

price

The price

of a product that

results in the most

efficient allocation

of an economy’s

resources.

fair-return

price

The price

of a product that

enables its producer

to obtain a normal

profit and that is

equal to the

average cost of

producing it.

Remembering that total cost includes a normal or “fair” profit, we see in Figure

10-9 that a fair-return price should be on the average-total-cost curve. Because the

demand curve cuts average total cost only at point f, clearly P

f

is the only price on

the demand curve that permits a fair return. The corresponding output at regulated

price P

f

will be Q

f

. Total revenue of 0afb will equal the utility’s total cost of the same

amount, and the firm will realize a normal profit.

Dilemma of Regulation

Comparing results of the socially optimal price (P = MC) and the fair-return price

(P = ATC) suggests a policy dilemma, sometimes termed the dilemma of regulation.

When its price is set to achieve the most efficient allocation of resources (P = MC),

the regulated monopoly is likely to suffer losses. Survival of the firm would pre-

sumably depend on permanent public subsidies from tax revenues. Conversely,

although a fair-return price (P = ATC) allows the monopolist to cover costs, it only

partially resolves the underallocation of resources that the unregulated monopoly

price would foster. That is, the fair-return price would increase output only from Q

m

to Q

f

in Figure 10-9, while the socially optimal output is Q

r

. Despite this dilemma,

regulation can improve on the results of monopoly from the social point of view.

Price regulation (even at the fair-return price) can simultaneously reduce price,

increase output, and reduce the economic profits of monopolies. (Key Question 11)

268 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

● Price discrimination occurs when a firm sells a

product at different prices that are not based on

cost differences.

●

The conditions necessary for price discrimination

are (1) monopoly power, (2) the ability to segre-

gate buyers based on demand elasticities, and

(3) the inability of buyers to resell the product.

● Compared with single pricing by a monopolist,

perfect price discrimination results in greater

profit and greater output. Many consumers pay

higher prices, but other buyers pay prices below

the single price.

● Monopoly price can be reduced and output

increased through government regulation.

● The socially optimal price (P = MC) achieves

allocative efficiency but may result in losses;

the fair-return price (P = ATC) yields a normal

profit but falls short of allocative efficiency.

De Beers, a Swiss-based cartel

controlled by a South African

corporation, produces about 50

percent of the world’s rough-cut

diamonds and purchases for re-

sale a sizable number of the

rough-cut diamonds produced

by other mines worldwide. As a

result, De Beers markets 63 per-

cent of the world’s diamonds

to a select group of diamond

cutters and dealers, but that

DE BEERS’ DIAMONDS: ARE

MONOPOLIES FOREVER?

De Beers was one of the world’s strongest and most

enduring monopolies. But in mid-2000 it announced

that it could no longer control the supply of diamonds

and thus would abandon its 66-year policy of

monopolizing the diamond trade.

chapter ten • pure monopoly 269

percentage has declined from 80

percent in the mid-1980s and

continues to shrink. Therein lies

De Beers’ problem.

Classic Monopoly Behaviour

De Beers’ past monopoly behav-

iour and results are a classic ex-

ample of the unregulated mo-

nopoly model illustrated in Figure

10-4. No matter how many dia-

monds it mined or purchased, De

Beers sold only that quantity of

diamonds that would yield an ap-

propriate (monopoly) price. That

price was well above production

costs, and De Beers and its part-

ners earned monopoly profits.

When demand fell, De Beers

reduced it sales to maintain price.

The excess of production over

sales was then reflected in grow-

ing diamond stockpiles held by

De Beers. It also attempted to

bolster demand through adver-

tising (“Diamonds are forever”).

When demand was strong, it in-

creased sales by reducing its dia-

mond inventories.

De Beers used several meth-

ods to control the production of

many mines it did not own. First,

it convinced a number of inde-

pendent producers that single-

channel or monopoly marketing

through De Beers would maxi-

mize their profit. Second, mines

that circumvented De Beers

often found their market sud-

denly flooded with similar dia-

monds from De Beers’ vast

stockpiles. The resulting price

decline and loss of profit often

would encourage the “rogue”

mine into the De Beers fold. Fi-

nally, De Beers simply pur-

chased and stockpiled diamonds

produced by independent mines

so their added supplies would

not undercut the market.

An End of an Era?

Several factors have come to-

gether to unravel the monopoly.

New diamond discoveries re-

sulted in a growing leakage of

diamonds into world markets

outside De Beers’ control. For

example, significant prospecting

and trading in Angola occurred.

Recent diamond discoveries in

Canada’s Northwest Territories

pose another threat. Although

De Beers is a participant in that

region, a large uncontrolled sup-

ply of diamonds is expected to

emerge. Similarly, although Rus-

sia is part of the De Beers’ mo-

nopoly, this cash-strapped coun-

try is allowed to sell part of its

diamond stock directly into the

world markets.

As if that were not enough,

Australian diamond producer

Argyle opted to withdraw from

the De Beers monopoly. Its an-

nual production of mostly low-

grade industrial diamonds ac-

counts for about 6 percent of the

global $8 billion diamond mar-

ket. The international media has

begun to focus heavily on the

role that diamonds play in fi-

nancing the bloody civil wars in

Africa. Fearing a consumer boy-

cott of diamonds, De Beers has

pledged not to buy these conflict

diamonds or do business with

any firms that does. These dia-

monds, however, continue to

find their way into the market-

place, eluding De Beers’ control.

In mid-2000 De Beer’s aban-

doned its attempt to control the

supply of diamonds. It an-

nounced that it planned to trans-

form itself from a diamond cartel

to a modern firm selling premium

diamonds and other luxury goods

under the De Beers label. It, there-

fore, would gradually reduce its

$4 billion stockpile of diamonds

and turn its efforts to increasing

the overall demand for diamonds

through advertising. De Beers

proclaimed that it was changing

its strategy to being “the dia-

mond supplier of choice.”

With its high market share

and ability to control its own

production levels, De Beers will

still wield considerable influence

over the price of rough-cut dia-

monds, but it turns out that the

De Beers monopoly was not

forever.