McKinney M. History and Politics in French-Language Comics and Graphic Novels

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

194

Amanda Macdonald

As Benoît Peeters (1994) reminds us, Töpffer intently discussed the rela-

tive valencies of the daguerreotype and drawing, not least as each medium

renders character, in the sense of human disposition. In a Europe where

physiognomy still held enormous sway, Töpffer was interested in inventing

character literally from scratch, in his “literature-in-pictures,” rather than

documenting it from existing reality.

7

Töpffer found an innovative balance

between an appeal to conventional recognition of character traits according

to features, and the fostering of a genuine dynamic of unfolding narrative

possibility for his characters. The line, the trait, is crucial for each of these

effects and for their interrelation, as is tellingly conveyed through Töpffer’s

insistence upon the value of accidents of “a single bound of the pen” in his

accounts of the inherent inventiveness of drawing. There is so much more

inventive potential in what “your pen has produced” than in “a preconceived

idea”: “the technique of line drawing fertilizes invention admirably: it is

quick, convenient, richly expressive, and apt for making happy discoveries”

(Töpffer 1965: 14). To gloss Töpffer in our terms, while remaining very close

to his own formulations, we can say that when the line performs its own

distractions, inventions of character are particularly likely to occur. Accidents

or no, the line is the thing, for in the throw of the line is a thought, which

is why Töpffer insists that one “see in [his] figures an idea and not limbs.”

8

The drawn line has another “advantage,” namely “the complete freedom that

it allows in your choice of features [traits] to be indicated—freedom that a

more finished imitation will no longer permit.” The point, here, is that mean-

ingfulness is the objective, not replication for its own sake, and meaningful-

ness arises out of graphic selection and emphasis. As Töpffer says of those

“limbs” that he draws to help inflect character, they have no intrinsic interest

qua limbs. Where particular emotions are to be depicted in a series of faces,

for example, it will be necessary to produce omissions by the standards of

naturalist completeness, omissions made in favor of those “linear signs which

convey these emotions” (Töpffer 1965: 7–8).

Not surprisingly, photography is, for Töpffer, the arch example of

thought-less completeness. Töpffer’s conviction is that the photographic

process produces mere identity (“the type of imitation proper to the plate”),

while drawing, particularly unschooled, accident-prone drawing of human

figures, produces the far more interesting and vital effect of resemblance

(“which is the kind of imitation proper to all products of Art”) (cited in

Peeters 1994: 47). In Töpffer’s idiom, resemblance is not synonymous with

simulacrum, since it renders the quality of its object precisely by eliminating

mere detail, whereas photographic identity is the slave of detail, helplessly,

195

Redrawing Ethnic Trajectories in New Caledonia

meaninglessly complete. Resemblance is a function of meaningfulness. Pho-

tographic processes, not executing a grapheme worthy of the name, cannot

achieve resemblance in the Töpfferian sense. And here is a final statement

on the matter from the 1841 article, “De la plaque Daguerre”: “Identity can

reproduce only a double of the object; the resemblance of the object taken

as a sign is able to draw out [make emerge], at will, this or that meaning,

this or that impression, this or that sentiment, this or that thought, and thus

transform the finite into the infinite, the painting into a poem, imitation into

art” (cited in Peeters 1994: 60). Töpffer’s infinite, his poem, his art, can serve

as cognates of distraction.

As Peeters rightly points out, Töpffer underrates the capacity of photog-

raphy to achieve “thought.” Nevertheless, by investing utterly in the graphic

trace from which all notions of “character” derive, Töpffer is able to gener-

ate complexities of character qua personae in novel relations between script

and imagery that conduct themselves upon pages, quite independently of

any biographical (past) entity of reference in the world. Among the many

implications of Töpffer’s work, the dissociation of character from reference

and indication, through idea-rich line work, for the discovery of a possible

“whole society” (Töpffer 1965: 13), vitally reveals the inventive potential of

bande dessinée as a nondocumentary mode of representation.

In the context of nation-making in New Caledonia, by extrapolation

from the logic of Töpffer’s polemic with the photograph, a warning may be

sounded about any monolithic installation of the culture of the document

by those wishing to serve the future of the proto-nation. The conjugation of

documentary photography with national history resolves into a concentration

of has-been-ness tending to produce meaningless doubling, identity as merest

repetition. Certainly, temporalization of this kind readily translates into the

sense of sure ground and firm purchase, but its counter-productivity in rela-

tion to invention means that the thought-prone, characterful trait of bande

dessinée recommends itself as a means of achieving significant, complemen-

tary distractions from history.

Iv. Bande dessinée ePIstemoLogy oF 1878 (toDay)

I wish to look at the role that bande dessinée may play in providing distrac-

tions from racialized, colonial history in the redrawing of race relations in

New Caledonia. I mean these puns quite literally: I would like to consider

what the generic conditions of bande dessinée (drawn strips)—line work that

196

Amanda Macdonald

is capable of drawing away from history and from photographic portrai-

ture—have to offer within the scheme of representations shaping New Cale-

donia’s proto-national character. I would suggest that bande dessinée invites

figurations of the nation involving characterful “bounds of the pen” rather

than indexicality, and offers a model of character-generation that is power-

fully face-driven, as becomes nation-making, without being past-oriented,

because it does not fall within the regime of the document. Race relations

amount very often to face relations. So we come to the relatively recent four-

album series of bandes dessinées by Bernard Berger and JAR (1998–2001),

Le sentier des hommes. Focusing on the third volume of the series, 18 78,

this discussion will situate Berger-JAR’s work in relation to two significant

histories of New Caledonia, in order to appreciate how it is that the Berger-

JAR enterprise contributes to the larger enterprise of knowing about New

Caledonia, where the more conventional knowledge practices of historici-

zation and documentation play such a strong role. Firstly, we will consider

the paradigmatic work of local history, Le mémorial calédonien through its

chapter on 1878, “Le grand brasier” [The Great Wildfire]. Berger-JAR’s ref-

erence to it is explicit, the better to offer an alternative project. Of precise

relevance, too, is a prior bande dessinée enterprise in a conventional histori-

cizing vein, Historial de la Nouvelle-Calédonie en bandes dessinées (Godard

and Loublanchès: no date, c. 1982), with its section on 1878, against which

1878 appears to define itself.

Le mémorial calédonien is, to date, a ten-volume, chronologically ordered

and historically driven account of “New Caledonia,” 1774–1988. It is likely to

be found in any settler family home, and indeed any public library in New

Caledonia, where it is still an actively used reference. The 1977 edition’s chap-

ter devoted to the events of 1878, “Le grand brasier,” constitutes its history of

1878 using starkly racialized terms and a patent us-and-them binary (“us”

being the French; “them” being “les Canaques”), even though “we” are all

citizens of the Republic “now,” in 1977. “Le grand brasier” presents the very

model of a text that can be said to silence and alienate an indigenous minor-

ity within a citizenry, negating in the forms and the institutions of history

the official gains of citizenship. Although the Mémorial implicitly aims to

use the historical function to consolidate New Caledonia as a country with

integral existence, the colonialist promotion of European civilization occurs

at the expense of nation-making. Nevertheless, the Mémorial is substantially

responsible for the iconography of 1878: it cites abundantly from archival

materials to illustrate its account. Let this briefest of readings of the Mémorial

record that there is a sense to its grab-bag accumulation of imagery.

197

Redrawing Ethnic Trajectories in New Caledonia

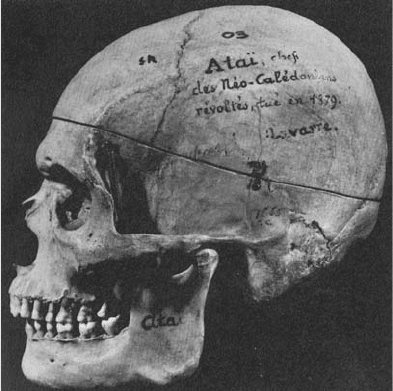

The strand of portraiture than runs through “Le grand brasier,” putting

faces to a large number of the historical personae, begins with a bold engrav-

ing of Ataï, in the most determined- and fierce-looking of the two widely

circulating portrayals of the warrior: he is depicted in the junior officer’s

jacket and képi that the French bestowed upon some chiefs, gimlet-eyed,

vital, and most intent of face.

9

The chapter closes, however, with three very

loaded inflections of the portraiture of Kanak: firstly, a photograph of a skull

in profile, bearing an inscription upon the cranium that reads, “Ataï, chef des

Néo-Calédoniens révoltés, tué en 1879” [Ataï, chief of the New Caledonians

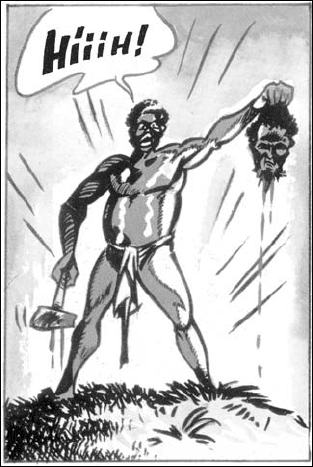

in revolt, killed in 1879] (figure 3). The second image is a photograph of an

armed Kanak militia member displaying the decapitated head of Noël Doui,

one of the leaders of the 1917 Kanak uprising, an event with which the chap-

ter is not concerned. Thirdly, a photograph depicts the low-relief plaque that

for many years adorned the base of a prominent statue in the heart of New

Caledonia’s capital, where defeated natives make obeisance to Governor Olry

Fig. 3. Uncaptioned photograph of a skull bearing the inscription,

“ataï, chef des néo-calédoniens révoltés, tué en 1879” [ataï,

chief of the new caledonians in revolt, killed in 1879], photo

-

gr

aph attributed to “j. oster, photothèque musée de l’homme.

palais de chaillot-paris,” no date, in philippe godard, “le grand

brasier,” Le mémorial calédonien, vol. 2: 1864–1899,

nouméa:

nouméa diffusion [editions d’art calédoniennes], 1977, pp.

176–232, p. 224.

198

Amanda Macdonald

(Godard, 1977: 224, 229, 232). The Mémorial presents the first photograph

without commentary, neither questioning the likelihood of this in fact being

Ataï’s skull (archival and eyewitness accounts report that the head of Ataï

was preserved in a jar ultimately housed at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris,

making it unlikely that this skull was Ataï’s), nor pointing out the error in

the dating of Ataï’s death (he was speared in an ambush, then decapitated by

Canala warriors in the presence of a French officer, on September 1, 1878).

The inclusion of the ghastly mortuary portrait of not-Ataï (i.e., Noël Doui’s

decapitated head) serves, most explicitly, to illustrate Kanak-against-Kanak

cruelty, while implicitly it gratifies the desire to fill the gap in the docu-

mentary iconography of Ataï’s downfall (a decapitated head is shown since

the decapitated head cannot be presented). The use of portraiture to ini-

tially posit excessively vital natives and then assert colonial triumph over

them is clear. Of more precise interest, here, is the effect of a perverse use of

documentary photography as anti-portraiture to affirm and reaffirm Ataï’s

deadness as a loss of faciality and character. The skull and the decapitation

photographs present as the undisguised urge of the photographic portrait, as

Barthes senses it: mortifaction. Having opened its facializing account of 1878

with the line-work portrait of Ataï that is most vital and characterful, the

Mémorial deploys photographic representations of the defunct Ataï and his

historical analogue, Noël, though they be false or impertinent documents,

in ways that exercise the documentary photograph’s that-has-been function

to most deadening effect. The stark dis-connect between word and image

functions in the text should be noted in this regard: while formal dissociation

is an inevitable function of the image-to-caption relation, it is nevertheless

worthwhile observing how excessively mute the depicted figures are. As we

shall see, the Berger-JAR response to the “Le grand brasier” is not to dismiss

its documentary base or to call its historical scholarship into question, but to

offer a genuine treatment of the Mémorial ’s iconographic creation, that is to

say a “traitement,” a reworking of it by the line, a reinvestment of its traits.

No such sense of line-work “treatment” applied when the Historial de la

Nouvelle-Calédonie en bandes dessinée was produced by the principal writer

of the Mémorial calédonien, Philippe Godard. Perhaps the first significant

bande dessinée work from New Caledonia, this four-volume, large-format

color work was clearly designed as a vibrant illustration of the history al-

ready elaborated in the Mémorial, and Godard’s “script” is ploddingly obedi-

ent to established, chronological history, a mere supplement. That said, what

emerges most forcefully as the specificity of “the history of New Caledonia in

bandes dessinées” is a faciality adapted from the repertoire of historical film

199

Redrawing Ethnic Trajectories in New Caledonia

drama: Governor Olry, recognizable from the portrait made known by the

Mémorial, is viewed in the manner of a realist film sequence, although given

a cartoon rendering when he explodes at the news of the massacre of Europe-

ans that initiates “1878”; Ataï, graphically hybridized from the two extant por-

traits that circulate, is figured first as a snarling stirrer of tribal passions, and

penultimately in a “close-up” of his grimacing death throes (Godard [c. 1982]:

68.6, 69.4-5, 94.1). These examples show the Historial ’s injection of never-

documented expressions of passion into the historico-documentary record.

As supplements, the facializing images offered by the Historial extrapolate

cooperatively from the available documents of photographic portraiture. The

creative potential of bande dessinée is thus confined to the production of “the

missing image” that the documentary record might itself have offered. This

collaboration with the documentary record is most starkly evident when the

Historial gratifyingly recasts the 1917 decapitation photograph of non-Ataï,

referred to above—which the Mémorial insisted on presenting, in defiance of

its historical impertinence—, so that here a tableau precisely analogous to the

“Noël” photograph is provided, one in which a dramatically inflected image

of Ataï’s own decapitated head can now be seen (figure 4).

Le sentier des hommes responds more inventively to the cinematographic

model that the Historial clearly registers. Providing, in its treatment of 1878,

the first serious bande dessinée rendition of New Caledonian pasts since the

Historial, the Berger-JAR collaboration

10

also takes issue with the documen-

tary record, rather than contenting itself to extrapolate from that record for

facial dramatics, as does the Historial.

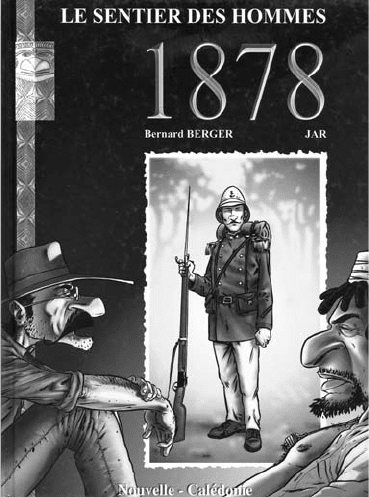

That the comic book 1878 has business with the document, with history,

and with national character, through the function of facialization, is given

form on the comic book’s color cover (figure 5).

11

Presenting a date for its

title, this third volume in the series strongly invokes historical moment as

its object, whereas volumes 1, 2, and 4 are concerned with thematic devices

suggestive of decidedly nonhistorical aspects of local humanity (“Langages,”

“Eternités,” “Ecorces”). Below the title, three men are figured in a triangu-

lated arrangement: in the left foreground, seated, facing inward as if facing a

campfire, a settler-French character is profiled, his morphology and clothing

inviting the appellation of “Caldoche”; to the right, somewhat closer, in pro-

file and supine, a Kanak character, also facing inward, i.e., as if sharing the fire

with the Caldoche figure, but from the other side; in the center background,

splitting the composition, an “old” black-and-white photograph is depicted,

its subject a French colonial soldier, standing for the portrayal, bearing arms

at rest, and facing outward. This triangulation takes up the principal terms of

200

Amanda Macdonald

New Caledonia’s present political situation, where, ever since the civil trou-

bles of the 1980s and the accords that flowed from those events, the country

has been formally constituted as a relation between loyalists and separat-

ists as mediated by the French state. In the shorthand of day-to-day politics,

the loyalists are oversimplistically racialized as “settler whites,” the separatists

somewhat more accurately summarized as “Kanak.” Here, the stark compo-

sitional separations among white settler, French state, and Kanak, repeat that

shorthand. While reinstating the colonial ethnic binary, these figures embody

the autonomizing New Caledonia of today. To take this eventful moment, this

post-1988 configuration, as the matter of a bande dessinée is unmistakably to

take up key elements both of New Caledonian history and of present-day

nation-making.

Fig. 4. Frame depicting the display of the decapi-

tated head of ataï by the canala warrior segou, in

philippe godard (script and text), eric loublanchès

(art), Historial de la Nouvelle-Calédonie en bandes

dessinées, vol. 2: Le temps des gouverneurs mili-

taires,

nouméa: nouméa editions [n.d., c. 1982], pp.

68–95, p. 94, frame 5.

201

Redrawing Ethnic Trajectories in New Caledonia

Just as overtly, the cover of 1878 designates the documentary portrait

photograph and marks it out as an object of bande dessinée reflection. In this,

it is acting quite independently of any established proto-national discussion,

yet we can understand 1878 to be articulating the generic issue that it is tak-

ing with documentary photography in terms of proto-national historiog-

raphy and nation-making. Whereas the soldier in the photograph is clearly

contemporary with 1878, the Caldoche and the Kanak figures are clothed in

ways favoring chronological ambivalence: neither fails to fit the historical

period, yet each, upon a second look, is also unproblematically of the pres-

ent day. The photograph is thus, by contrast, emphatically marked as a past-

bound document, just as the emissary of the French state that it depicts is

perspectivally the most distant character. This twofold distanciation involves

a diminishment of the soldier’s photo-paper-pale face, while the two “New

Caledonian” faces are large, subtly defined, and luminous—indeed, as if lit

by the firelight of imminent nationhood. The point is elementary: the face is

the metonym for the proto-national character, a bande dessinée face defined

Fig. 5. Front cover, Bernard Berger-jaR, Le sentier des hom-

mes, vol. 3: 1878,

nouméa: la Brousse en Folie, 1999.

202

Amanda Macdonald

against the documentary photographic portrait, in an ambiguous relation-

ship to “the past” of 1878.

Certainly, as its title and cover affirm, 1878 takes the history of 1878 as its

ground. Whereas the first two volumes of the series, Eternités and Langages,

deal in Kanak pre-origin time and foundation stories, in the third volume,

from the first frame, European colonization is abruptly in place, its historical

time proceeding: “Nouvelle-Calédonie, quelque part en brousse—1877—La

colonisation européenne s’étend peu à peu à toutes les terres qui peuvent

servir de paturage au bétail” (page 7, frame 1). [New Caledonia, somewhere

in the bush—1877—European colonization is spreading, little by little, to all

the land suitable as pasture for cattle.] The first pages of the album adopt

the standard approach for bande-dessinée history, as per the Historial, that

of informally illustrating established passages from conventional works of

history. The documentary record serving that history is cited: the famous

quip of anticolonial grievance, commonly attributed to Ataï, appears on the

first page: “ ‘Quand mes tarots iront manger tes boeufs, je mettrai une bar-

rière’ avait répondu un Mélanésien qu’un éleveur voulait obliger à enclore

ses cultures . . . ” (7.4). [“ ‘When my tarots go eating your cattle I will put up a

fence,’ a Melanesien had replied to a farmer who wanted to make him enclose

his gardens . . . ”] The naval ship, La Vire, is duplicated from its photograph

in the Mémorial (Berger and JAR, 8.1). As in the Historial, the formal portrait

of Governor Olry used in the Mémorial has clearly been the reference for his

subtly expressive appearance in this, his second bande dessinée performance

(8.2–3; 10.3; 11.2–3; 12.2). Likewise, an adaptation of the Hughan photo used

by the Mémorial makes the officer Servan instantly recognizable (34.1, 3, 4).

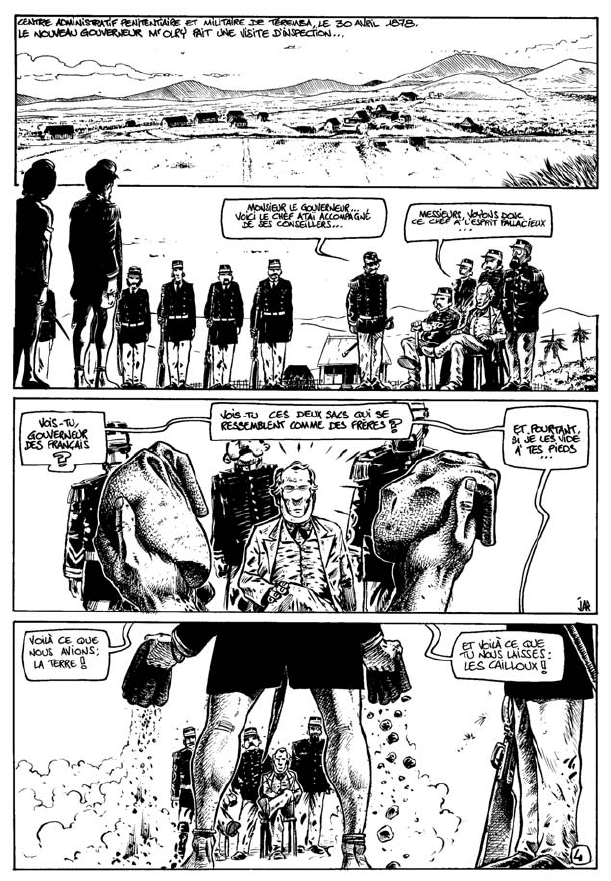

Ataï is depicted from behind and on a small scale, yet we perceive the reverse

view, as it were, of the engraved portrait of Ataï cited in the Mémorial, since

he is depicted in képi and military jacket, his head posed here at a cocky angle

(10.2; figure 6). The famous skull sepultures are also quickly introduced, once

again recognizable from history’s use of documentary photographs that re-

peatedly shows them, as here, clustered in a grove (9.5; cf Bensa: 32). And it

is in the depiction of the skulls that a very specifically bande dessinée project

becomes discernible, one that is concerned to do something rather more than

supplement the documentary record as if a bande dessinée “camera” were fill-

ing in the gaps between history’s various pictorial documents.

This frame, in which a female elder is appealing to the sepulchral ances-

tors (9.5), puts us in Kanak mythological reality, not so much in the past tense

perhaps as in a mood other than the indicative. It places us in the presence

of the timeless ancestors who exist in the shape of skulls. These characters,

203

Redrawing Ethnic Trajectories in New Caledonia

Fig. 6. Full page representing ataï’s reproach to governor olry, Bernard Berger-jaR, Le sentier des

hommes, vol. 3: 1878,

nouméa: la Brousse en Folie, 1999, p. 10, frames 1–4.