Pike Robert, Neal Bill. Corporate finance and investment: decisions and strategy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

.

Chapter 10 Setting the risk premium: the Capital Asset Pricing Model 255

is not due to measurement errors or random influences, then it is appropriate to

reassess the assumptions. The ensuing analysis, based on an amended set of assump-

tions, may lead to the generation of alternative predictions that accord more closely

with reality.

■ The assumptions of the CAPM

The most important assumptions are as follows:

1 All investors aim to maximise the utility they expect to enjoy from wealth-holding.

2 All investors operate on a common single-period planning horizon.

3 All investors select from alternative investment opportunities by looking at expect-

ed return and risk.

4 All investors are rational and risk-averse.

5 All investors arrive at similar assessments of the probability distributions of

returns expected from traded securities.

6 All such distributions of expected returns are normal.

7 All investors can lend or borrow unlimited amounts at a similar common rate of

interest.

8 There are no transaction costs entailed in trading securities.

9 Dividends and capital gains are taxed at the same rates.

10 All investors are price-takers: that is, no investor can influence the market price by

the scale of his or her own transactions.

11 All securities are highly divisible, i.e. can be traded in small parcels.

Several of these assumptions are patently untrue, but it has been shown that the

CAPM stands up well to relaxation of many of them. Incorporation of apparently

more realistic assumptions does not materially affect the implications of the analysis.

A full discussion of these adjustments is beyond our scope, but van Horne (2000) offers

an excellent analysis.

10.9 PORTFOLIOS WITH MANY COMPONENTS:

THE CAPITAL MARKET LINE

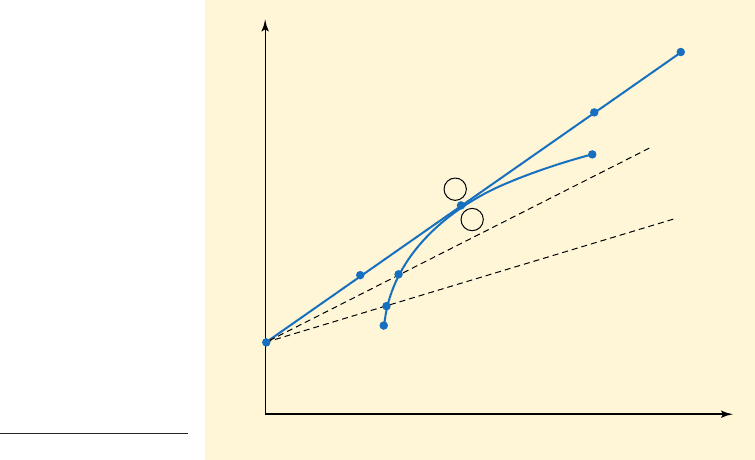

The theory behind the CAPM revolves around the concept of the ‘risk–return trade-off’.

This suggests that investors demand progressively higher returns as compensation for

successive increases in risk. The derivation of this relationship, known as the capital

market line (CML), relies on the portfolio analysis techniques examined in Chapter 9.

The reader may find it useful to re-read Section 9.7, where we explained the deri-

vation of the efficient set available to an investor who can invest in a large number of

assets. One conclusion of this analysis was that the only way to differentiate between

the many portfolios in the efficient set was to examine the investor’s risk–return pref-

erences, i.e. there was no definable optimal portfolio of equal attractiveness to all

investors.

■ Introducing a risk-free asset

The above conclusion applies only in the absence of a risk-free asset. A major contribu-

tion of the CAPM is to introduce the possibility of investing in such an asset. If we allow

for risk-free investment, the range of opportunities widens much further. For example,

on Figure 9.5 which is based on Figure 9.5 which showed an efficient frontier of AE,

consider the line from the return available on the risk-free asset, passing through

point T on the efficiency frontier. This represents all possible combinations of the

R

f

,

CFAI_C10.QXD 3/15/07 7:28 AM Page 255

.

256 Part III Investment risk and return

Separation Theorem

A model that shows how indi-

vidual perceptions of the opti-

mal portfolio of risky securities

is independent (i.e. separate

from individuals’ different risk-

return preferences)

risk-free asset and the portfolio of risky securities represented by T. To the left of T, both

portfolio return and risk are less than those for T, and conversely for points to the right

of T. This implies that between and T the investor is tempering the risk and return

on T with investment in the risk-free asset (i.e. lending at the rate ), while above T, the

investor is seeking higher returns even at the expense of greater risk (i.e. he borrows in

order to make further investment in T).

However, the investor can improve portfolio performance by investing along the

line representing combinations of the risk-free asset and portfolio V. He or she can

do better still by investing along the tangent to the efficient set. This schedule

describes the best of all available risk–return combinations. No other portfolio of risky

assets when combined with the risk-free assets allows the investor to achieve higher

returns for a given risk. The line becomes the new efficient boundary.

Portfolio W is the most desirable portfolio of risky securities as it allows access to

the line If the capital market is not already in equilibrium, investors will com-

pete to buy the components of W and tend to discard other investments. As a result,

realignment of security prices will occur, the prices of assets in W will rise and hence

their returns will fall; and conversely, for assets not contained in W. The readjustment

of security prices will continue until all securities traded in the market appear in a

portfolio like W, where the line drawn from touches the efficient set. This adjusted

portfolio is the ‘market portfolio’ (re-labelled as M), which contains all traded securities,

weighted according to their market capitalisations. For rational risk-averting investors, this is

now the only portfolio of risky securities worth holding.

There is now a definable optimal portfolio of risky securities, portfolio M, which all

investors should seek, and which does not derive from their risk–return preferences.

This proposition is known as the Separation Theorem – the most preferred portfolio is

separate from individuals’ attitudes to risk. The beauty of this result is that we need

not know all the expected returns, risks and covariances required to derive the effi-

cient set in Figure 10.8. We need only define the market portfolio in terms of some

widely used and comprehensive index.

However, having invested in M, if investors wish to vary their risk–return combi-

nation, they need only to move along lending or borrowing according to their

risk–return preferences. For example, a relatively risk-averse investor will locate at

point G, combining lending at the risk-free rate with investment in M. A less cautious

R

f

MZ,

R

f

R

f

WZ.

R

f

WZ

R

f

WZ,

R

f

V,

R

f

R

f

Expected return on portfolio (ER

p

)

R

f

Risk of portfolio (standard deviation, s

p

)

Capital

market line

(CML)

Z

H

W

G

E

T

V

A

M

Figure 10.8

The capital market line

CFAI_C10.QXD 3/15/07 7:28 AM Page 256

.

Chapter 10 Setting the risk premium: the Capital Asset Pricing Model 257

capital market line

A relationship tracing out the

efficient combinations of risk

and return available to investors

prepared to combine the

market portfolio with the risk-

free asset

investor may locate at point H, borrowing at the risk-free rate in order to raise his or

her returns by further investment in M, but incurring a higher level of risk. However,

we would still need information on attitudes to risk to predict how individual investors

behave.

The line is highly significant. It describes the way in which rational investors

– those who wish to maximise returns for a given risk or minimise risk for a given

return – seek compensation for any additional risk they incur. In this sense,

describes an optimal risk–return trade-off that all investors and thus the whole mar-

ket will pursue; hence, it is called the capital market line (CML).

■ The capital market line

The CML traces out all optimal risk–return combinations for those investors astute

enough to recognise the advantages of constructing a well-diversified portfolio. Its

equation is:

Its slope signifies the rate at which investors travelling up the line will be compen-

sated for each extra unit of risk, i.e. units of additional return.

For example, imagine investors expect the following:

so that

Every additional unit of risk that investors are prepared to incur, as measured by

the portfolio’s standard deviation, requires compensation of two units of extra return.

With a portfolio standard deviation of 2 per cent, the appropriate return is:

for for and so on.

Anyone requiring greater compensation for these levels of risk will be sorely dis-

appointed.

To summarise, we can now assess the appropriate risk premiums for combinations

of the risk-free asset and the market portfolio, and therefore the discount rate to be

applied when valuing such portfolio holdings. The final link in the analysis of risk

premiums is an explanation of how the discount rates for individual securities are

established and hence how these securities are valued. This was already provided by

the discussion of the SML in Section 10.6.

s

p

4%, ER

p

18%;s

p

3%, ER

p

16%;

ER

p

10% 12 2%2 14%

c

ER

m

R

f

s

m

d c

20% 10%

5%

d 2

s

m

5%

ER

m

20%

R

f

10%

1ER

m

R

f

2>s

m

ER

p

R

f

c

1ER

m

R

f

2

s

m

ds

p

R

f

MZ

R

f

MZ

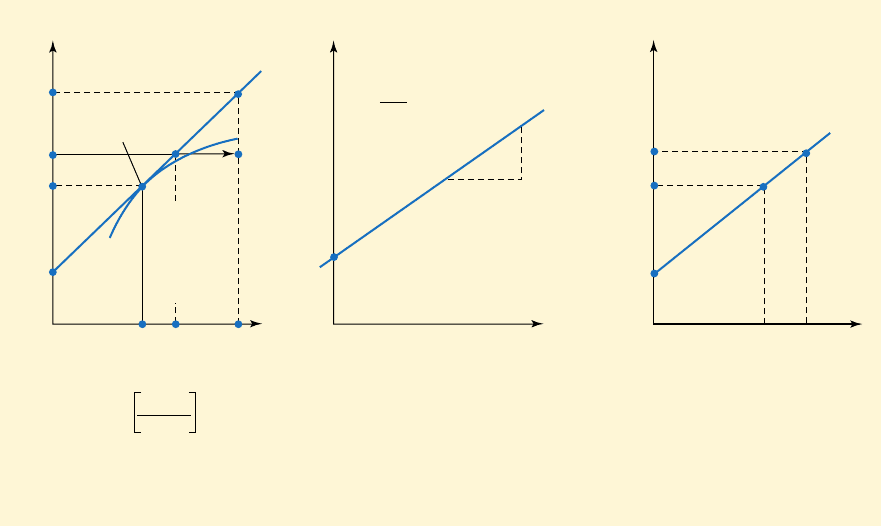

10.10 HOW IT ALL FITS TOGETHER: THE KEY RELATIONSHIPS

The CAPM on first acquaintance may look complex. However, its essential simplicity

can be analysed by reducing it to the three panels of Figure 10.9.

Panel I shows the CML, derived using the principles of portfolio combination

developed in Chapter 9. The CML is a tangent to the envelope of efficient portfolios of

risky assets, the point of tangency occurring at the market portfolio, M. Any combina-

tion along the CML (except M itself) is superior to any combination of risky assets

alone. In other words, investors can obtain more desirable risk–return combinations by

CFAI_C10.QXD 3/15/07 7:28 AM Page 257

.

258 Part III Investment risk and return

mixing the risk-free asset and the market portfolio to suit their preferences, i.e. accord-

ing to whether they wish to lend or borrow.

The slope of the CML, given by defines the best available terms for

exchanging risk and return. It is desirable to hold a well-diversified portfolio of secu-

rities in order to eliminate the specific risk inherent in individual securities like C.

When holding single securities, investors cannot expect to be rewarded for total risk

(e.g. 15 per cent for C) because the market rewards investors only for bearing the undi-

versifiable or systematic risk. The extent to which risk can be eliminated depends on

the covariance of the share’s return with the return on the overall market. Hence, the

degree of correlation with the return on the market influences the reward from hold-

ing a security and thus its price.

The characteristics line in Panel II shows how the return on an individual share,

such as C, is expected to vary with changes in the return on the overall market. Its

slope, the Beta, indicates the degree of systematic risk of the security.

The security market line in Panel III shows the market equilibrium relationship

between risk and return, which holds when all securities are ‘correctly’ priced. Clearly,

the higher the Beta, the higher the required return. Although Beta is not a direct meas-

ure of systematic risk, it is an important indicator of relevant risk.

The decomposition of the overall variability, or variance, of the share’s return into

systematic and unsystematic components is explained in the appendix to this chapter.

It can be demonstrated by focusing on security C in Panel III of Figure 10.9. Security

C lies to the north-east of the market portfolio because its Beta of 1.3 exceeds that of

the overall market. If the market as a whole is expected to generate a return of 20 per

cent, and the risk-free rate is 10 per cent, C’s expected return is:

This reward compensates only for systematic risk, rather than for the share’s total

risk. Of the total risk of C, represented by distance OD, only OE is relevant.

The risk–return trade-off, given by the slope of the CML, is 120% 10% 2>5% 2,

ER

C

10% 1.3 120% 10%2 10% 13% 23%

31ER

m

R

f

2>s

m

4

b

= 1

b

= 1.3

b

(10%)

MM

C(23%)

(20%)

(10%)

(23%)

(20%)

ER

c

ER

m

R

f

ΔER

j

ΔER

m

ER

m

000

α

b

=

ER

j

ER

ER

c

ER

m

R

f

ER

j

s

m

(5%)

40%

BA

C

CL

SML

Z

DE

(15%)

s

Optimal portfolio

of risky assets

PANEL I

The capital market line (CML) The characteristics line (CL) The security market line (SML)

ER

p

=

R

f

+

Indicates the required risk premium

for any

portfolio

comprising the

risk-free asset and the market

portfolio of risky assets.

s

p

ER

m

−

R

f

s

m

Expresses the relationship between

the

expected

return on security

j

for given values of the return expected

on the portfolio.

(Slope =

b

, measured from past data

by regression analysis).

ER

j

=

R

f

+

b

j

[ER

m

−

R

f

]

Indicates the appropriate required

return on

individual

assets

(and

also inefficient portfolios).

CML

PANEL II

PANEL III

All inefficient

portfolios and

individual assets

in this space – for

asset C.

AB = Syst. risk

BC = Unsyst. risk

R

f

MZ summarises efficient

portfolios of M plus risk-free asset

Information about ER

j

also appears

on the CML diagram, e.g. viz, asset C,

which has greater systematic risk

than the market portfolio

ΔER

j

ΔER

m

Figure 10.9 The CAPM: the three key relationships

CFAI_C10.QXD 3/15/07 7:28 AM Page 258

.

Chapter 10 Setting the risk premium: the Capital Asset Pricing Model 259

10.11 RESERVATIONS ABOUT THE CAPM

Self-assessment activity 10.10

You expect the stock market to rise in the next year or so. Could you beat the market

portfolio by holding, say, the five securities with the highest Betas?

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

The CAPM analyses the sources of asset risk and offers key insights into what rewards

investors should expect for bearing these risks. However, certain limitations detract

from its applicability.

■ It relies on a battery of ‘unrealistic’ assumptions

It is often easy to criticise theories for the lack of realism of their assumptions, and cer-

tainly, many of those embodied in the CAPM, especially concerning investor behav-

iour, do not seem to reflect reality. However, if the aim is to provide predictions that can

be tested against real world observations, the realism of the underlying assumptions is

secondary. Obviously, if the predictions themselves do not accord reasonably closely

with reality, then the theory is undoubtedly suspect.

■ Single time period

A key assumption of the CAPM is that investors adopt a one-period time horizon for

holding securities. Whatever the length of the period (not necessarily one year), the rates

of return incorporated in investor expectations are rates of return over the whole hold-

ing period, assumed to be common for all investors. This provides obvious problems

when we come to use a required return derived from a CAPM exercise in evaluating an

investment project. Quite simply, we may not compare like with like. If an investor

requires a return of, say, 25 per cent, over a five-year period, this is rather different from

saying that the returns from an investment project should be discounted at 25 per cent

p.a. Attempts have been made, notably by Mossin (1966), to produce a multi-period ver-

sion of the CAPM, but its mathematical complexity takes it out of the reach of most prac-

tising managers, especially those inclined to scepticism about the CAPM itself.

since the risk of the market itself is 5 per cent. For C, with overall risk of 15 per cent,

we would not expect to obtain compensation at this rate (i.e. giving

an overall return of 40 per cent), because much of the total risk can be diversified away.

Observe that a variety of required return figures could have emerged from our

calculation – in fact, anything along the perpendicular ZD in Panel I of Figure 10.9,

depending on the extent to which security C is correlated with the market portfolio.

The nearer C lies to Z, the greater the correlation and the higher the required return,

and conversely, should C be nearer to D. This reflects the changing balance between

the two risk components along ZD.

If the market rewarded total risk, the return offered on security C would be the

risk-free rate of 10 per cent supplemented by the risk–return trade-off (

security

risk of 15 per cent), yielding a total of 40 per cent. However, because the total

risk is partly diversifiable, the market offers a return of just 23 per cent for security C.

This relationship is indicated on Panel I of Figure 10.9 by the distances AB and BC, rep-

resenting respectively the systematic and specific risk components of security C’s total

risk (not to scale).

2 the total

2 15% 30%

CFAI_C10.QXD 3/15/07 7:28 AM Page 259

.

260 Part III Investment risk and return

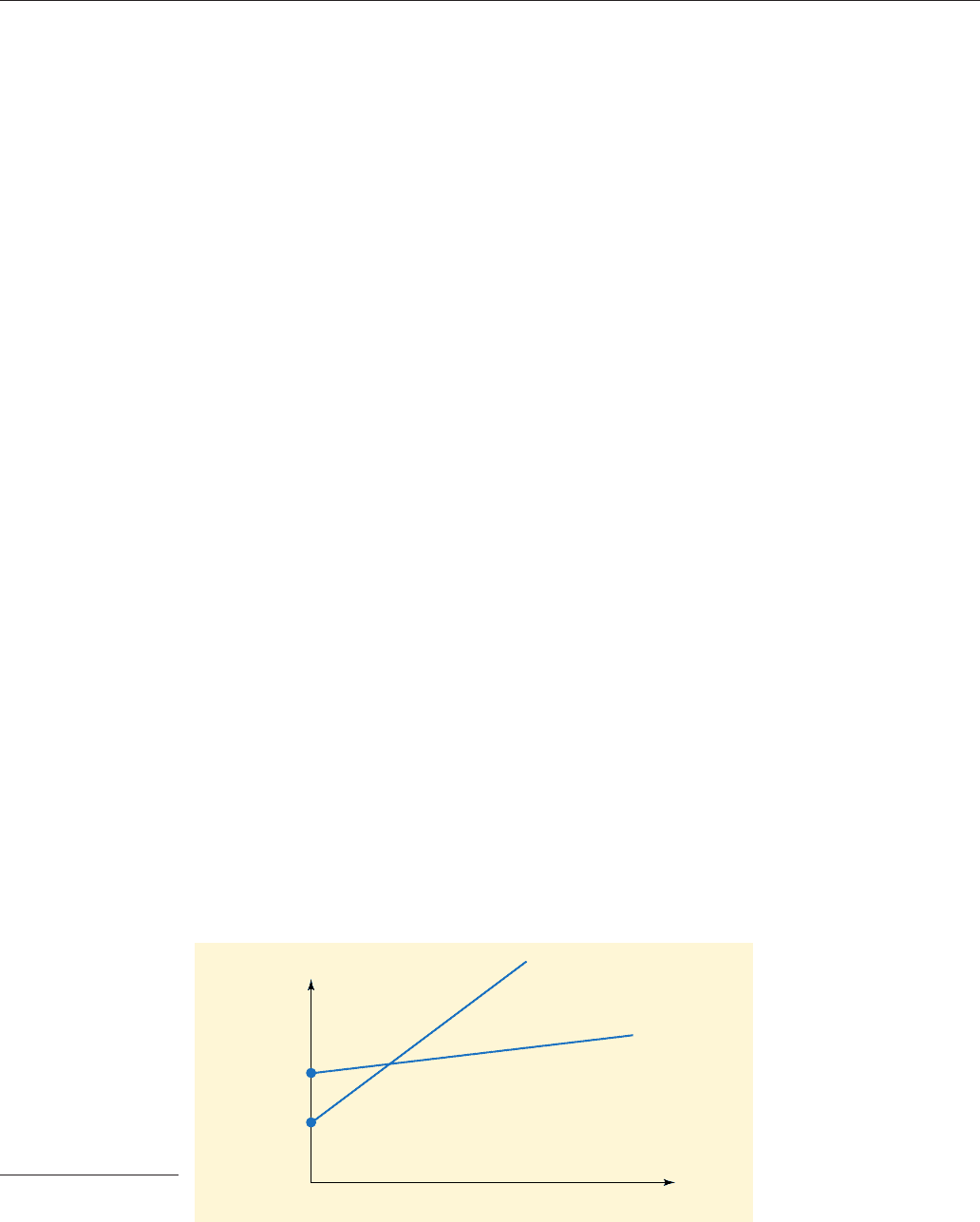

Empirical SML

Theoretical SML

Expected and

actual returns

R

f

R

f

0

Beta

Figure 10.10

Theoretical and

empirical SMLs

Many writers have observed that, in principle, the CAPM is untestable, since it is based

on investors’ expectations about future returns, and expectations are inherently awk-

ward to measure. Hence, tests of the CAPM have to examine past returns and take

these as proxies for future expected returns, based on a key premise. If a long enough

period is examined, mistaken expectations are likely to be corrected, and people will

come to rely on past average achieved returns when formulating expectations. Greatly

simplified, the essence of the research methods is as follows.

Research usually proceeds in two stages. First, using time series analysis over a

lengthy period applied to a large sample of securities (say 750), researchers estimate

both the Beta for each security and its average return. Relying heavily on market effi-

ciency, these estimates are taken to be estimates of the ex ante expected return, i.e. it is

assumed that rational investors will be strongly influenced by past returns and their

variability when formulating future expectations.

Second, the researcher tries to locate the SML to investigate whether it is upward slop-

ing, as envisaged by the CAPM. The 750 pairs of estimates for Beta and the average return

for each security are used as the input into a cross-section regression model of the form:

where is the expected return from security i, is the intercept term (i.e. the risk-free

rate), is the slope of the SML and is an error term.

If the CAPM is valid, the measured SML would appear as in the steeper line on

Figure 10.10, with an intercept approximating to recorded data for the risk-free rate:

for example, the realised return on Treasury Bills.

Several early studies (e.g. Black et al., 1972; Fama and McBeth, 1973) did seem to

support the positive association between Beta and average stock returns envisaged by

the CAPM for long periods up to the late 1960s. However, evidence began to emerge

that the empirical SML was much flatter than implied by the theory and that the inter-

cept was considerably higher than achieved returns on ‘risk-free’ assets.

Some researchers have continued to test the validity of the CAPM, but others, fol-

lowing Ross (1976), have concluded that some of the ‘rogue’ results stem from intrin-

sic difficulties concerning the CAPM that make it inherently untestable. In the process,

they have developed an alternative theory, based on the Arbitrage Pricing Model

(APM), discussed in Section 10.13.

Some of the reasons why the CAPM is thought to be nigh impossible to test ade-

quately are as follows:

1 It relies on specification of a risk-free asset – there is some doubt whether such an

asset really exists.

2 It relies on analysing security returns against an efficient benchmark portfolio, the

u

i

a

2

a

1

R

i

R

i

a

1

a

2

b

i

u

i

10.12 TESTING THE CAPM

CFAI_C10.QXD 3/15/07 7:28 AM Page 260

.

Chapter 10 Setting the risk premium: the Capital Asset Pricing Model 261

10.13 FACTOR MODELS

It is not too surprising that some of the studies listed in the previous section do not sup-

port the notion that Beta is the most important determinant of the return on quoted

securities. In the CAPM, the only independent variable driving individual security

returns is the return on the market, i.e. there is a single factor at work. In reality, every-

one knows there are many factors at work, but the researcher is hoping that their vari-

ous impacts will all be rolled up into this single market factor.

However, the returns on a share react to general industry or sector changes in addi-

tion to general market changes. These aspects are all confused in Beta. This helps

explain why the CAPM is such a poor explanatory model. The explanatory power of

a regression model like the CAPM is measured by the R-Squared, or Coefficient of

Determination, which is measured on a scale of zero to These are shown in Table 10.4

in the final column. While expert opinions vary on this, it is commonly accepted that

an R-Squared of above 50 per cent indicates a strong relationship, i.e. a high degree of

explanatory power. The highest figure shown in the table is 42 per cent. The interpre-

tation we have to put on this is that there are other, perhaps many other, factors at

work impacting on security returns.

Whereas the CAPM is a single factor model, many researchers like Fama and French

(1992) have attempted to develop multi-factor models. A multi-factor model will include

two elements:

■ a list of factors that have been identified as having a significant influence on security

returns

1.

market portfolio, usually proxied by a widely-used index. Because no index captures

all stocks, the index portfolio itself could be inefficient, as compared with the full

market portfolio, thus distorting empirical results.

3 The model is unduly restrictive in that it includes only securities as depositories of

wealth. A full ‘capital asset pricing model’ would include all forms of asset, such as

real estate, oil paintings or rare coins – in fact, any asset that offers a future return.

Hence, the CAPM is only a security pricing model.

Fama and French (1992) made a thorough test of the CAPM, finding no evidence for

the ‘correct’ relationship between security returns and Beta over the period 1963–90.

The cross-section approach supported neither a linear nor a positive relationship. It

appeared that average stock returns were explained better by company size as meas-

ured by market capitalisation, large firms generally offering lower returns, and by the

ratio of book value of equity to market value, returns being positively associated with

this variable. They concluded that rather than being explained by a single variable,

Beta, security risk was multi-dimensional.

Neither of the UK studies conducted by Beenstock and Chan (1986) and by Poon and

Taylor (1991) found significant positive relationships between security returns and Beta.

Acting on Levis’ (1985) observation for the period 1958–82 that smaller firms tend to out-

perform larger firms (although erratically), Strong and Xu (1997) attempted to replicate

the Fama and French analysis in a UK context. Specifically, they investigated whether

Beta could explain security returns and whether it was outweighed by ‘the size effect’.

For the period 1960–92, they found a positive risk premium associated with Beta in

isolation, but this became insignificant when Beta was combined with other variables

in a multiple regression. For the whole period, market value dominated Beta, but over

1973–1992, it was itself insignificant compared with book-to-market value of equity,

and gearing. However, the explanatory power of various combinations of variables

used was poor, never exceeding an of 8 per cent. Overall, there appeared to be a size

effect, but it did not operate in as clear or as stable a fashion as in the Fama and French

study of US data.

R

2

CFAI_C10.QXD 3/15/07 7:28 AM Page 261

.

262 Part III Investment risk and return

■ a measure of the sensitivity of the return on particular securities’ returns to changes

in these factors.

In the CAPM, there is only the one factor, the return on the market portfolio, and the

sensitivity is measured by each security’s Beta. As in the CAPM, which distinguish-

es between specific and market-related risk, there are two types of risk – factor risk,

and non-factor risk. Thus, variations in the returns on stocks can be explained by

variations in the identified factor(s) (analogous to market risk) and variations due to

background ‘noise’, i.e. changes in factors not included in the model (analogous to

specific risk).

■ A two-factor model

In the UK, 60 per cent of the economy is represented by consumer expenditure, which is

largely driven by income growth and the ‘feel-good factor’ from rising house prices.

Bear also in mind that the stock market is generally supposed to herald movements in

the overall economy one to two years ahead. Therefore, a model devised to explain stock

market returns in terms of interest rates and house prices would be quite plausible.

This would be a two-factor model of the following form:

,

and are

the two identified factors, interest rates and house prices,

and

.

The values of the parameters a, and would be found by multiple regression

analysis, while the error term is assumed to average zero. Say the values established

by empirical investigation are:

This means that for every 1 per cent point change in interest rates, individual secu-

rity returns change by twice as much, i.e. by two percentage points. Similarly, for every

1 per cent point change in the house price index, security returns change by 0.2 of a

percentage point.

It should be stressed that the explanatory factors in the equation would be common

to all firms, but the sensitivity coefficients, the ‘Betas’, would vary according to how

closely ‘geared’ the returns on each firm were to each factor. For example, if one iden-

tified factor was the sterling/dollar exchange rate, we would expect to see much high-

er sensitivity for a firm exporting to, or operating in, the USA, compared to one

conducting most of its operations in the domestic arena.

b

2

0.2

b

1

2.0

a 0.01

b

2

b

1

e

j

is an error termcoefficients

are the sensitivityb

1

and b

2

F

2

F

1

a is the intercept termwhere R

j

is the return on stock j in the usual sense,

R

j

a b

1

F

1

b

2

F

2

e

j

10.14 THE ARBITRAGE PRICING THEORY

The most fully developed multi-factor model is the Arbitrage Pricing Theory (APT),

developed by Ross (1976). Unlike the CAPM, APT does not assume that shareholders

evaluate decisions within a mean–variance framework. Rather, it assumes the return on

a share depends partly on macroeconomic factors and partly on events specific to the

company. Instead of specifying a share’s returns as a function of one factor (the return

CFAI_C10.QXD 3/15/07 7:28 AM Page 262

.

Chapter 10 Setting the risk premium: the Capital Asset Pricing Model 263

on the market portfolio), it specifies the returns as a function of multiple macroeco-

nomic factors upon which the return on the market portfolio depends.

The expected risk premium of a particular share would be:

where is the expected rate of return on security j, is the expected return on

macroeconomic factor 1, is the sensitivity of the return on security j to factor 1 and

is the random deviation based on unique events impacting on the security’s returns.

The bracketed terms are thus risk premiums, as found in the CAPM.

Diversification can eliminate the specific risk associated with a security, leaving

only the macroeconomic risk as the determinant of required security returns. A ration-

al investor will arbitrage (hence the name) between different securities if the current

market prices do not give sufficient compensation for variations in one or more factors

in the APT equation.

The APT model does not specify what the explanatory factors are; they could be the

stock market index, Gross National Product, oil prices, interest rates and so on.

Different companies will be more sensitive to certain factors than others.

In theory, a riskless portfolio could be constructed (i.e. a ‘zero Beta’ portfolio) which

would offer the risk-free rate of interest. If the portfolio gave a higher return, investors

could make a profit without incurring any risk by borrowing at the risk-free rate to

buy the portfolio. This process of ‘arbitrage’ (i.e. taking profits for zero risk) would

continue until the portfolio’s expected risk premium was zero.

The Arbitrage Pricing Theory avoids the CAPM’s problem of having to identify the

market portfolio. But it replaces this problem with possibly more onerous tasks. First,

there is the requirement to identify the macroeconomic variables. American research

indicates that the most influential factors in explaining asset returns in the APT frame-

work are changes in industrial production, inflation, personal consumption, money

supply and interest rates (McGowan and Francis, 1991).

Tests of the APT, especially for the UK, are still in their relative infancy. However,

Beenstock and Chan (1986) found that, for the period 1977–83, the first few years of the

UK’s ‘monetarist experiment’, share returns were largely explained by a set of mone-

tary factors – interest rates, the sterling M3 measure of money supply and two differ-

ent measures of inflation, all highly interrelated variables. In 1994, Clare and Thomas

reported results from analysing 56 portfolios, each containing 15 shares sorted by Beta

and by size of company by value. For the Beta-ordered portfolios, the key factors were

oil prices, two measures of corporate default risk, the Retail Price Index (RPI), private

sector bank lending, current account bank balances and the yield to redemption on UK

corporate loan stock. Using portfolios ordered by size, the key factors reduced to one

measure of default risk and the RPI. Again, there was much intercorrelation among

variables, but the return on the stock market index, although included in the initial

tests, appeared in none of these final lists.

Once the main factors influencing share returns are established, there remain the

problems of estimating risk premiums for each factor and measuring the sensitivity of

individual share returns to these factors. For this reason, the APT is currently only in

the prototype stage, and yet to be accepted by practitioners.

e

j

b

1

ER

factor 1

ER

j

ER

j

R

f

b

1

1ER

factor 1

R

f

2 b

2

1ER

factor 2

R

f

2

p

e

j

10.15 ISSUES RAISED BY THE CAPM: SOME FOOD FOR

MANAGERIAL THOUGHT

The CAPM raises a number of important issues, which have fundamental implications

for the applicability of the model itself and the role of diversification in the armoury of

corporate strategic weapons.

CFAI_C10.QXD 3/15/07 7:28 AM Page 263

.

264 Part III Investment risk and return

■ Should we trust the market?

Legally, managers are charged with the duty of acting in the best interests of share-

holders, i.e. maximising their wealth (although company law does not express it quite

like this). This involves investing in all projects offering returns above the shareholders’

opportunity cost of capital. The CAPM provides a way of assessing the rate of return

required by shareholders from their investments, albeit based partly on past returns. If

the Beta is known and a view is taken on the future returns on the market, then the

apparently required return follows. This becomes the cut-off rate for new investment

projects, at least for those of similar systematic risk to existing activities. This implies

that managers’ expectations coincide with those of shareholders or, more generally,

with those of the market. If, however, the market as a whole expects a higher return

from the market portfolio, some projects deemed acceptable to managers may not be

worthwhile for shareholders.

The subsequent fall in share price would provide the mechanism whereby the mar-

ket communicates to managers that the discount rate applied was too low. The CAPM

relies on efficiently-set market prices to reveal to managers the ‘correct’ hurdle rate

and any mistakes caused by misreading the market. The implication that one can trust

the market to arrive at correct prices and hence required rates of return is problematic

for many practising managers, who are prone to believe that the market persistently

undervalues the companies that they operate. Managers who doubt the validity of the

EMH are unlikely to accept a CAPM-derived discount rate.

■ Should companies diversify?

The CAPM is based on the premise that rational shareholders form efficiently diversi-

fied portfolios, realising that the market will reward them only for bearing market-

related risk. The benefits of diversification can easily be obtained by portfolio formation,

i.e. buying securities at relatively low dealing fees. The implication of this is that corpo-

rate diversification is perhaps pointless as a device to reduce risk because companies are seeking

to achieve what shareholders can do themselves, probably more efficiently. Securities are far

more divisible than investment projects and can be traded much quicker when condi-

tions alter. So why do managers diversify company activities?

An obvious explanation is that managers have not understood the message of the

EMH/CAPM, or doubt its validity, believing instead that shareholders’ best interests

are enhanced by reduction of the total variability of the firm’s earnings. For some

shareholders, this may indeed be the case, as a large proportion of those investing

directly on the stock market hold undiversified portfolios.

Many small shareholders were attracted to equity investment by privatisation

issues or by Personal Equity Plans and their successor, ISAs (Individual Savings

Accounts). Larger shareholders sometimes tie up major portions of their capital in a

single company in order to take, or retain, an active part in its management. In such

cases, market risk, based on the co-variability of the return on a company’s shares with

that on the market portfolio, is an inadequate measure of risk. The appropriate meas-

ure of risk for capital budgeting decisions probably lies somewhere between total risk,

based on the variance, or standard deviation, of a project’s returns, and market risk,

depending on the degree of diversification of shareholders.

A more subtle explanation of why managers diversify is the divorce of ownership

and control. Managers who are relatively free from the threat of shareholder interfer-

ence in company operations may pursue their personal interests above those of share-

holders. If an inadequate contract has been written between the manager-agents and

the shareholder-principals, managers may be inclined to promote their own job secu-

rity. This is understandable, since shareholders are highly mobile between alternative

security holdings, but managerial mobility is often low. To managers, the distinction

CFAI_C10.QXD 3/15/07 7:28 AM Page 264