Roberts A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: from 1905 to 1940

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BRITISH WEST AFRICA AND LIBERIA

and rural capitalist. During the 1890s, J. K. Coker, J. H. Doherty

and

a

number

of

other merchants

in

Lagos ventured into

plantation agriculture

to

compensate for their weakening com-

mercial position. In 1907 they formed the Agege Planters Union

to protect their own interests while promoting cocoa cultivation

through propaganda and assistance

to

small farmers. Simultan-

eously, news

of

their cocoa wealth, carried back

to

the Ondo

hinterland

by

plantation labourers, attracted attention. Cocoa,

however, was particularly dependent upon the export trade since

the beans had no domestic use. When a combination of low world

prices and local buying agreements by exporters led to

a

50 per

cent drop in Gold Coast producer prices in 1908, a group of cocoa

farmers near Kumasi staged a brief hold-up. A number of chiefs,

who were themselves cocoa farmers, supported the ban but they

came under government censure

for

interfering with trade.

Official reaction thus favoured the companies, which were under

little pressure to increase producer prices given alternative supplies

and the weakness of the market. Poorer farmers could not afford

not to sell, many of the chiefs bowed to government intimidation,

and the wealthy farmers rushed to sell lest the price fell further.

Yet, save for momentary setbacks such

as

the 1908 cocoa slump,

price incentives

for

export cultivation remained high.

The

dramatic increase in export production of the pre-war period was

the result of increased use of land and labour, as well as investment

in new tools and seeds, by numerous small-scale farmers. In many

areas this was facilitated

by

rural capital accumulation

and

consumer demands arising from the rubber boom of the 1890s,

when uncontrolled exploitation had led to the widespread destruc-

tion of wild latex-bearing plants. In turn, long-term investment

during this period was

to

lay the foundation for the post-war

recovery of the 1920s; this was especially true of cocoa, a tree-crop

which does not mature for at least seven years. Moreover, export

growth was generally achieved without widespread dislocation or

diminution of the subsistence sector, which remained the mainstay

of the domestic economy. The household remained the basic unit

of production, though

the

responses

of

farmers frequently

involved the innovative adaptation

of

indigenous institutions.

Thus traditional family and kinship obligations were used

to

mobilise labour and capital,

as

instanced

by

the formation

of

'companies'

in

the Akwapim cocoa region for the purchase of

412

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH WEST AFRICA, I905-I914

land. Furthermore, as land assumed a new value as a means of

obtaining wealth, the transition from communal to individual

ownership deplored by the Land Committee: became replicated as

land became a marketable commodity. The landed rural capitalist

class,

often themselves originally 'stranger farmers', began to

employ migrant labour anxious to amass capital in an increasingly

moneyed economy. By 1910 there may already have been as

many farm labourers as farmers in the Gold Coast cocoa-

growing

areas,

part of

a

process of increasing rural socio-economic

differentiation.

8

It was, however, the colonial government, as the largest

employer of labour, which was primarily responsible for the

creation of the African proletariat, with all its socio-political

ramifications. The colonial system could not have functioned

without African employees, who

filled

a

wide range of subordinate

administrative and technical posts: soldiers and police, forest

rangers and agricultural assistants, legions of messengers and

clerks. The public works and railway departments, which required

large numbers of artisans and unskilled labour, even ran their own

training programmes. Yet, like the better-educated African white-

collar workers in government service, both the permanently

employed skilled workers and the less secure semi-skilled and

unskilled labourers had experienced a deterioration of their real

incomes and conditions of service around the turn of the century.

Consequently there were strikes by skilled personnel, such as

those of

the

Nigerian railway clerks in 1902 and 1904 (which were

supported by unskilled railway workers and the African press).

The immediate reaction of British officials was uncompromising.

Strikes were viewed as a direct challenge to colonial authority.

Scab labour and violence were used to break strikes; workers were

fired upon during the 1911 Sierra Leone railway strike. Yet

through such pressure at a time of increasing demand for their

services, skilled employees were able to obtain wage increases of

35 to 50 per cent between 1906 and 1914. As for the unskilled,

whose daily wage remained fairly static until after the Second

World War, the rapid upward mobility helped ease labour

relations. On the other hand, British officials and businessmen

tended to regard labour costs in British West Africa as excessive,

* Polly Hill, The migrant cocoa-farmers of

southern

Ghana: a study in rural capitalism

(Cambridge, 1965), 17.

413

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH WEST AFRICA AND LIBERIA

despite the gross imbalance between their own income and that

of their employees: yd to is per day for an unskilled labourer, £36

to £48 per annum for a skilled carpenter and joiner, as compared

to £300

per

annum plus allowances

for the

lowest-ranking

administrative cadet in Nigeria.

The British colonial system was fraught with contradictions.

Development and exploitation necessitated the incorporation of

increasing numbers into the colonial economy, yet the government

sought to rule through a system of local administration based on

indigenous socio-political institutions.

The

cautious, well-

intentioned paternalism of British indirect rule, with its concern

for controlled change in harmony with local cultures, lent itself

to

a

narrow preservationist 'zoo-keeper' mentality. Nowhere

were the paradoxes more glaring than

in

the areas of education

and missionary endeavour. Privately, junior officials were not

infrequently concerned that the forces of change introduced by

commercial and missionary activities might lead to local unrest,

thereby adversely reflecting on their own abilities to control their

districts and thus their prospects

for

promotion

or

transfer

to

more prestigious postings. British officials were not unaware of

the need for educated youths if the 'native administrations' were

to be 'modernised', with properly written records and accounts.

Mission schools far outnumbered and often predated government

institutions, being at the centre of evangelisation, and the source

of future generations of converts. Yet missionary education and

Christianity were indiscriminate in their impact. They tended

to

attract those with the least stake

in

the system and thus most

inclined to challenge it, often encouraged by missionary denunc-

iation of local beliefs and practices. The prevailing official attitude

was dominated by the English 'public school' model and elitist

principles. These held that such limited education as was necessary

was best restricted to the sons

of

chiefs, as

at

the government

schools of Kano, in Northern Nigeria, and Bo, in Sierra Leone.

The fact that chiefs were suspicious and often sent the sons of

slaves

or

commoners to school was

a

problem

to

be overcome

by persuasion, and coercion if required. Missionary activities were

greatly restricted in the Muslim areas of Northern Nigeria, on the

grounds that their presence would

be

antagonistic

to

local

religious sensibilities, and also

in

the less closely administered

hinterland, such as the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast,

414

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

GERMAN WEST AFRICA, 1905-1914

in the interest of safety and security. In the long term, this

protectionist policy left the peoples of these peripheral regions

ill-prepared to respond to the demands of modern political

economies.

In 1912 Lugard was recalled to Nigeria, in order to unify its

administration. The Colonial Office hoped both to rationalise the

railway policies of the two dependencies and also relieve the

British tax-payer of the burden of the recurrent Northern Nigerian

deficit by charging it against the revenue derived from Southern

Nigeria's export duties. As governor of both dependencies,

Lugard supervised their amalgamation in January 1914, when he

became governor-general. This union was very imperfect. The

transfer of administrative staff between south and north, and even

between Muslim and 'pagan' areas within the north, was very

rare;

differences in land policy persisted; while technical services

such as agriculture, education, police and prisons remained

separate until the 1920s.

GERMAN WEST AFRICA, 1905-1914

The year 1905 witnessed crises and turmoil within Germany's

African

empire.

Rebellions in German East Africa and South West

Africa, and scandals concerning the cruelty and immorality of

officials in Togo and Kamerun, had focused attention on the need

for reform. In 1906 a new

Kolonialdirektor,

Bernhard Dernburg,

was appointed and a colonial ministry was established in 1907,

further strengthening the already considerable control which

Berlin exercised over its colonial governors. Simultaneously the

reorganisation brought to office new governors, Count Julius von

Zech in Togo and Theodore Seitz in Kamerun, who were more

sympathetic to African grievances though no less determined to

wrest an economic return from the colonies. Colonial conquest,

which had been prolonged and bloody, due as much to the

difficulties of vanquishing numerous small fragmentary polities as

to alleged German militarism, was giving way to more settled

administration and economic exploitation.

In both Togo and Kamerun the governor was assisted by an

exclusively German advisory council composed of an official

majority with unofficial representatives of German settler,

commercial and missionary interests. African representation was

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH WEST AFRICA AND LIBERIA

conspicuously absent.

It

had been discussed by the governors'

councils and in the colonial advisory council in Berlin, but rejected

for fear

of

encouraging African opposition and lessening

the

influence of unofficial interests. Towards the end of the period,

debate shifted

to

the admission

of

African traditional leaders,

along the lines which were adopted in British West African terri-

tories during

the

1920s,

but the

possibility

of

constitutional

innovation was cut short by the outbreak of war in 1914.

In the hinterland of Togo and Kamerun, German administ-

ration tended

to

resemble British indirect rule; shortages

of

German staff and resources meant reliance upon existing African

authorities

as

agents

of

control.

In

1913

the

total German

personnel in district administration, including clerks, numbered

only 26 in Togo and 47 in Kamerun, while the annual budget of

Togo was less than that

of

Berlin University. Districts were

administered

by

adventurous young German military officers,

colonial refugees from

a

peacetime army who were not unlike their

British counterparts. They were assisted by a quasi-military police

force as well as the backing of regular colonial troops in Kamerun.

There were no such troops in Togo, but the police, armed with

rifles plus three machine-gun units, were commanded by German

military officers

and

capable

of

operating

as a

military unit.

' Chiefs' who were recognised by the governor were allowed

to

exercise considerable power subject

to

periodic administrative

supervision.

As in

British West Africa, this

not

infrequently

resulted

in

local 'big men' being given authority over peoples

over whom they had no traditional claim, while once powerful

overlords had their position undermined by government recog-

nition

of

subordinates as independent authorities. The 'chiefs',

who were generally assigned one or two policemen to assist them,

were responsible for mobilising draft labour, collecting taxes of

which they retained a portion, and trying minor civil and criminal

cases in accordance with native law and custom, fruitful areas for

petty corruption. Only the more determined colonial subjects

took appeals to the German administrator; colonial justice, based

on the

Be^irksleiterrecht,

an unspecified combination

of

German

law and local custom, was unpredictable and harsh. Flogging was

a common punishment, giving rise to a protracted official debate

in Togo over the relative merits of the local leather lash and the

officially prescribed rhino-hide whip.

416

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

GERMAN WEST AFRICA, 1905-1914

German rule was more direct in the settled coastal areas, the

Ewe territory of southern Togo and the regions around Duala,

Victoria and Mt Cameroun, where there were already numerous

mission-educated Africans, an established African entrepreneurial

elite,

and a developing export economy. In Lome, the capital of

Togo,

a five-man advisory city council was established in 1908,

chaired by the district officer with two Togolese members.

However, such African representation was exceptional. In addit-

ion to the usual racial prejudices and reluctance by colonial

authorities to allow subject peoples access to power, the western-

ised black elite in Togo and Kamerun were at the special

disadvantage of being mainly English-speaking:

a

reflection of the

pre-colonial dominance of English commerce and of Anglo-

American missionary education in these

areas.

Consequently there

was increasing government pressure for the introduction of

German language instruction in the schools. On the other hand,

German officials were no less concerned than their British

counterparts over the ' detribalisation' of increasing numbers of

Africans through education: 13,746 enrolled in Togo in

1911,

and

over 34,000 in Kamerun. In Togo, the reformist governor Zech

established a rehabilitation camp at Atakpame for the instruction

of detribalised offenders in 'productive labour'.

The role of guardian of African interests was assumed by the

German missionaries. They normally spoke the local languages

and were acknowledged as authorities on the indigenous cultures

of the coastal regions: mission societies were barred from the

Muslim areas of the hinterland. Most educated Africans had been

to mission schools; in 1911 almost all elementary schools in both

Togo and Kamerun were mission institutions. In Togo the North

German Mission had been instrumental in exposing the excesses

of officials and the dubious land claims of the German Togo

Company, while in Kamerun the Basel Mission was particularly

active. The latter not only defended African land rights against

German planters, it established a trading company to provide

good wares at reasonable prices, and a bank at Duala which paid

4 per cent interest to Africans and helped finance 'Christian'

development, such as a soft-drink bottling factory at Duala to

compete with the liquor import trade. Such activities resulted in

direct clashes with German commercial interests but, however

well-intentioned, the missionaries were imperfect spokesmen for

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH WEST AFRICA AND LIBERIA

African opinion. Frequently themselves in conflict with African

beliefs and customs, they were less critical of their own goals and

behaviour, often co-operating in the exploitation of the land and

labour of those they claimed to protect. African grievances were

eloquently expressed

in a

Togolese petition

in

1913 which

requested black representation

on the

governor's council,

a

written code of

justice,

equality before the law for black plaintiffs

in cases of mixed jurisdiction, improved prison conditions, an end

to chaining and corporal punishment,

a

reduction

in

head-tax

from twelve

to six

marks, and free trade. This petition was

ignored.

Ironically,

in

view

of

the scorn subsequently heaped upon

German colonial rule, both British and French officials regarded

German accomplishments with considerable envy and respect;

Togo

in

particular seemed

to

many

a

model colony. Such

admiration

was

elicited

not by

Germany's treatment

of the

African population but by her economic exploitation: the healthy

balance of trade and revenue of

the

colonies. The scale and nature

of development in the two German West African territories were

quite distinct. Togo had a population of just over a million, most

of whom lived

in

the southern coastal half of its 34,000 square

miles.

Kamerun covered nearly 192,000 square miles (expanded

to 292,000 square miles under the 1911 convention with France

following the second Moroccan crisis) and had

a

population of

just over three million scattered over a wide range of climate and

topography.

In an

attempt

to

exploit Kamerun,

the

German

government had granted large territorial concessions to German

trading firms whose agents did much to open up the interior, while

near

the

coast most

of

the fertile land

on the

slopes

of

Mt

Cameroun behind Victoria was alienated to German planters. The

colonial economy of Kamerun thus resembled the concessionary

system of Belgian and French Equatorial Africa. In contrast, the

export economy of Togo was based on the more common West

African model of commercial exploitation of African production.

Attempts were made to establish Kamerun-style plantations by

the German Togo Company,

but

like similar companies

in

Kamerun

it

was an under-capitalised speculative venture which

proved unequal to the task. Among the most successful planters

in Togo were the Afro-Brazilians, such as Octaviano Olympio

who pioneered the copra industry, or the d'Almeida, Ayavon and

418

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

GERMAN WEST AFRICA, I905-I914

Creppi families whose rubber-tree holdings in the Anecho region

far exceeded those of the German planters. Nonetheless, they were

prevented from competing with

the

commercial sector

by

regulations prohibiting Africans from importing

and

exporting

goods

and

produce except through European agents. Infra-

structural developments

and

technological research was largely

financed by state capitalism, through loans and grants from

the

imperial government. With

a

transport network comprising 203

miles of railways in 1914, compared to 193 miles in Kamerun, and

755 miles

of

surfaced roads suitable

for

motor traffic, German

investment

in

Togo was much more impressive

in its

impact,

bearing favourable comparison with other territories

in

tropical

Africa. Moreover, by careful supervision of government expend-

iture,

relatively high direct taxation

in the

settled areas

and

caravan tolls

in the

interior, income from customs duties

and

railway receipts and extensive use of'political labour', Togo won

the distinction

of

being

the

only German colony

in

Africa

to

maintain

a

balanced budget.

By

1914, both Togo and Kamerun

had postal, telegraph

and

telephone services,

as

well

as

marine

cable connections with Europe.

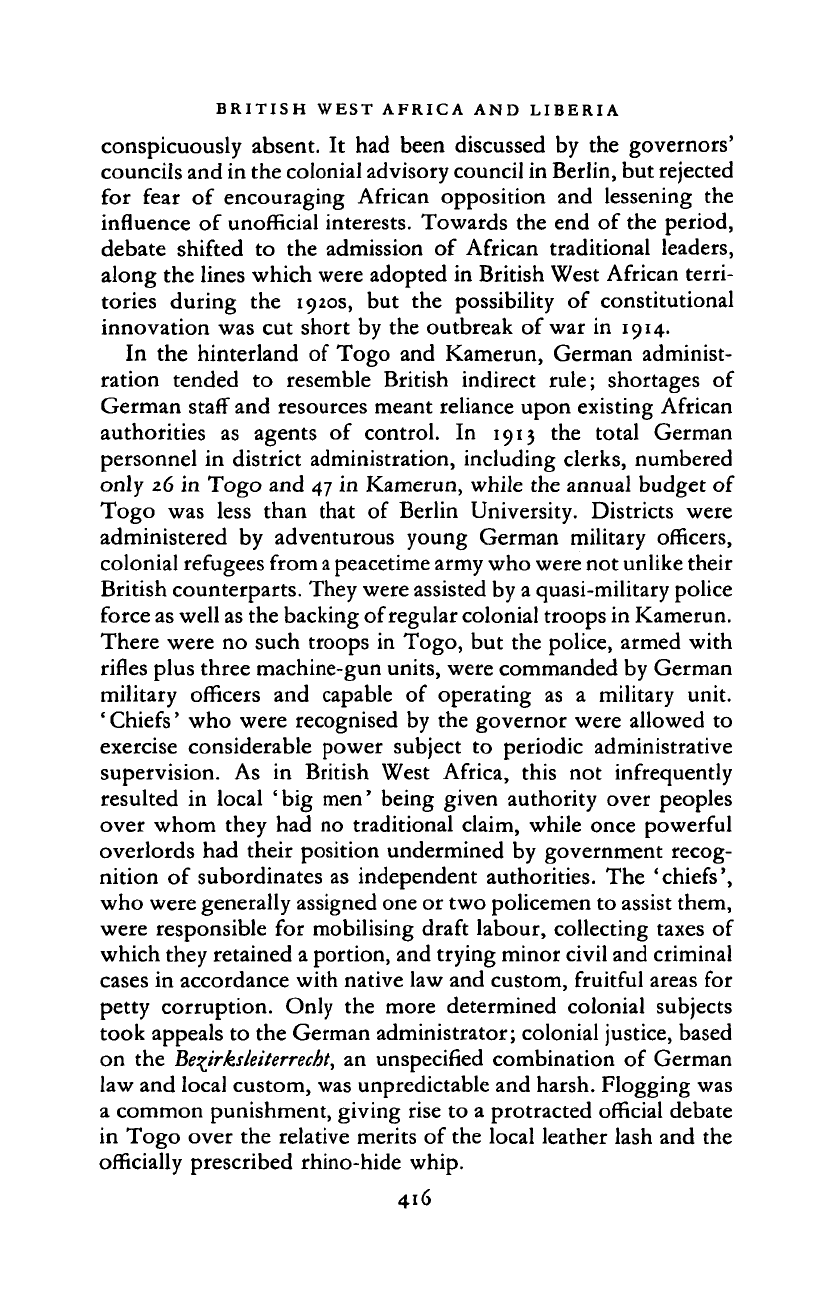

Between 1905

and

1912

the

external trade

of

Togo increased

in value

by 86 per

cent and that

of

Kamerun

by

154

per

cent

9

.

Yet

a

significant proportion

of

the imports was consumed by the

increasing European population

of

Kamerun (1,871

in

1914),

while rubber, which was obtained almost exclusively from native

collectors rather than plantations, constituted nearly half

the

export value. Many

of

the Kamerun plantations were just begin-

ning

to

come into commercial production

of

crops such

as

tobacco, cocoa and coffee when overtaken by war in 1914. Despite

considerable investment

in

agricultural experimentation and free

distribution of cotton seed, the dream of liberation from depend-

ence upon American cotton supplies through

the

development

1905

1912

Imports

£579.855

£571,59'

Togo

Exports

£•93.685

£497.945

Kamerun

Imports

£656,880

£1,670,000

Exports

£454.390

£1,136,000

Source:W.

A.

Crabtree, ' Togoland', Journal

of

the African Society, 1914/191 j,

14, 175;

H.

R.

Rudin, Germans in the

Cameroon!,

1884-1914 (London, 1958),

283.

419

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH WEST AFRICA AND LIBERIA

of extensive West African cotton exports proved as illusory for

the Germans

as for

the British. The short-staple West African

strains, while well suited

to

local hand looms, attracted

a

poor

price on the world market. Rather than experiment with varieties

introduced from abroad, Africans preferred to grow other crops

for which there was

a

ready market. Besides, European agro-

nomists had hardly begun to come to terms with the complexities

of tropical agriculture, and their advice was often worse than

useless.

Economic development was often achieved

at a

considerable

cost

in

African land and labour. By 1905 most of the slopes of

Mt Cameroun had been alienated to German plantations and all

'unoccupied' land in Kamerun had been declared crown land. In

Togo the German Togo Company laid claim to vast areas based

on dubious treaties from the 1890s. Like the British, German

authorities were encountering the thorny problems

of

African

land rights and notions of sale, ownership, and usufruct of land.

In many instances, local African communities were left with

insufficient land

for

subsistence agriculture, much less export

production. The mission societies, while defending African inter-

ests,

were themselves anxious

to

obtain ownership

of

land

for

schools and churches. Agricultural instruction was introduced in

the schools

in

the hope of somehow improving African yields.

Farming students

at

the agricultural school at Nuatja, in Togo,

were amongst

a

limited category, including certain African

government employees and advanced mission pupils, exempt

from taxation. The German Togo Company's concessions were

drastically reduced and a system of land leasing replaced outright

sale to aliens. Togolese could also challenge government claims

to ' unoccupied' land and a land register was established: policies

which encouraged the move toward individual ownership and

favoured the more literate elite. Local land commissions with

missionary representation were set up in Kamerun, but they failed

to provide solutions; they merely supervised

the

removal

of

African communities from plantations

to

reserves. The most

serious confrontation occurred in Kamerun when the government

decided to expropriate native property in Duala. The native town

was said to be a health hazard, though European speculators were

willing to pay high prices to the Duala for waterfront property

in the hope of profiting by the boom of the port city and railway

420

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

GERMAN WEST AFRICA, 1905-1914

terminus. King Manga Bell sent protests to the Reichstag

throughout 1912 and 1913, pointing out that the land was

guaranteed to the Duala under the treaty of

1884.

.Colonial officials

were intransigent. In desperation, Manga Bell tried to rally local

opposition to German rule and sought support from Britain and

France. He was arrested and hanged for treason on the eve of the

war.

Shortage of cheap labour was another recurrent problem in

Togo and Kamerun. While motorable roads and railways reduced

transport costs and liberated labour hitherto engaged in porterage,

their construction required large levies of 'political labour'. In

1907 a system of six-month contract labour was introduced in

Togo in order to establish a more stable semi-skilled labour force

for railway construction. Workers received 75 pfennigs

(approximately 9d) per nine-hour day, but at least one-third of

their wages was deposited in compulsory savings accounts in an

official effort to institute concepts of 'thrift'. Africans were

generally regarded as indolent, one of the justifications for forced

labour being its 'educative' value. District officers in northern

Togo,

a labour reserve, recruited work gangs for both government

and plantations, the latter constituting a constant demand. The

situation was particularly bad in Kamerun, where the plantations

were in the moist malarial coastal areas, while much of the labour

was recruited through 'chiefs' in the elevated hinterland

grassfields where malaria was less prevalent. Often exhausted

from the long trek to the coast, isolated from their families and

culture, fed upon a diet of plantain which was also used to provide

shade cover for the young cocoa and coffee bushes, workers soon

contracted malaria, a new and thus more virulent form of

dysentery, or some other disease; many died. The commercial

firms were vociferous in their condemnation of the planters'

wasteful labour policy since it threatened their own markets and

supplies. They feared the creation of

a

destitute rural proletariat

too poor to buy their goods. On the other hand, German traders

and missionaries impressed large numbers of African porters in

areas away from the road and rail network, which meant

throughout most of Kamerun and northern Togo. In Togo,

competing demands for labour by officials, planters, merchants

and missionaries, combined with relatively high taxation and low

wages, led to alarming emigration into the British Gold Coast.

421

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008