Roberts A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: from 1905 to 1940

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BRITISH WEST AFRICA AND LIBERIA

BRITISH WEST AFRICA, 1905-1914

By 1905 the era of colonial conquest was drawing to a close

and British West Africa was entering a period of administrative

consolidation. In the interests of economy, Lagos and Southern

Nigeria were united in May 1906, to form the Colony and

Protectorate of Southern Nigeria. Yet on such basic issues as land

policy, Nigeria remained a divided 'multiple dependency'. In

Lagos Colony a system of freehold land tenure based on Crown

grants issued to original African claimants operated. In Southern

Nigeria African ownership of the land was recognised, subject to

certain regulations designed to prevent alienation to non-Africans.

In Northern Nigeria, almost all the land was 'nationalised' and

all rights to land were vested in the government as trustee. This

eliminated what many colonial officials regarded as the vexatious

problems of land litigation and individual ownership, as distinct

from rights of occupancy, though it did not prevent a shift from

communal towards individual rights. British rule thus super-

imposed legal and bureaucratic diversity upon a heterogeneous

complex of indigenous cultures and polities.

' Punitive patrols' persisted but increasingly they took the form

of police operations against isolated communities in connection

with criminal cases, as defined by the colonial authorities, or in

reprisal for failure to pay taxes or supply labour. They were thus

part of the process of defining the relationship between the new

colonial government and African societies. At the local level,

administrators were preoccupied with identifying and reaching an

accord with traditional indigenous authorities through whom the

colonial oligarchy might rule the vast African population. With

only one British administrator for every 100,000 Africans in

Northern Nigeria, and five administrative officers for the entire

Sierra Leone Protectorate with a population of over one million,

2

day-to-day responsibilities for maintaining law and order, mobili-

sing labour and/or collecting taxes devolved upon the local

African authorities.

Known as ' indirect rule', the system reached its fullest elabor-

ation in Northern Nigeria. Here Sir Frederick Lugard (high

commissioner, 1901-6) had found the sophisticated Hausa-Fulani

government and Islamic judiciary well suited to his needs; it was

2

Figures based on censuses of Northern Nigeria in 1926 and Sierra Leone in 1921.

402

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH WEST AFRICA, I905-I914

strengthened by the system of' native treasuries' developed by

H. R. Palmer between

1906

and

1911.

However, the popularisation

of the emirate model as an administrative paradigm by Lugard

and his supporters not only influenced British perceptions and

colonial policies but also obscured both its limitations and earlier

analogous developments elsewhere in Southern Nigeria, the Gold

Coast, Sierra Leone and the Gambia. The result was a profusion

of arrangements whereby multifarious indigenous authorities —

Yoruba monarchs, subordinate chiefs of the once mighty Asante

confederation or parochial Limba leaders — were recognised as

'chiefs' by the relevant British governor and were allowed to

exercise often quite wide-ranging powers, particularly judicial

authority, subject to varying degrees of administrative

supervision.

Among the Ibo, Tiv and numerous other acephalous societies

where no such person of authority existed, ' chiefs' were created

in accordance both with the demands of administrative expediency

and with European theories of evolutionary political tutelage,

chieftaincy being regarded as a ' natural' form of African govern-

ment. Colonial officers wanted agents to whom they could issue

instructions and whom they could hold responsible for carrying

them out. In chiefless societies such as the Tiv, this frequently

resulted in the elevation of 'marginal men', those imperfectly

socialised into indigenous culture who thus had least to lose and

most to gain from siding with British authorities, or alien Africans

(e.g. Hausa) from stratified societies who were prepared to

cooperate with the British. Yet such individuals lacked close

familiarity with local customs or the dynamics of parochial power

and their new responsibilities, by definition, brought them into

conflict with indigenous political norms.

In the case of stratified, hierarchical societies such as the Hausa

or Yoruba, the impact of colonial rule was initially less dramatic.

Though incumbent rulers who resisted the loss of their sov-

ereignty were removed, the British lavished considerable attention

on the subtleties of succession and protocol. However, the

authority of traditional rulers no longer rested on the consent of

the people or of powerful factions within the community but were

derived from the governor. It was a power relationship which

astute chiefs, such as

alafin

Ladugbola of

Oyo,

were to manipulate

to negate indigenous constitutional constraints on autocracy,

403

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH WEST AFRICA AND LIBERIA

remove potential rivals and even expand their sphere of authority.

At their best, African authorities acted as mediators between the

colonial oligarchy and the people, channelling and interpreting

information, instructions

and

ideas.

On the

other hand,

the

dependence of the British on local rulers inclined them to turn

a blind eye to exactions and abuses of power by men such as Emir

Aliyu

of

Zaria. Only serious breaches

of

the law, such

as

embezzlement of government funds or murder, or the threat of

serious popular unrest, led to the removal of

a

colonial

chief,

and

then generally to exile rather than imprisonment. Nevertheless,

it was

to

such rulers, rather than the Western-educated African

elite,

that the colonial government increasingly turned for advice,

thereby reinforcing British conservative and autocratic biases.

By the turn

of

the century there was already an established

educated elite of African doctors, lawyers, clergy and businessmen

in the coastal areas, who were accustomed to playing an active

role in the political and social life of the community. Predomin-

antly, though not exclusively, Christian, they were imbued with

the sombre middle-class Victorian tones

of

their missionary

teachers and models, yet permeated with distinct and vibrant local

hues.

A

common educational experience, often physically and

emotionally demanding, and a common language, English, gave

the elite

a

sense of unity, reinforced by social, commercial and

marital links. They frequently travelled

to

other parts

of

West

Africa, as well as Britain, on business and family matters; and

collateral branches of prominent families were often to be found

in the trading emporia along the coast. Through such contacts,

through correspondence and the lively African press, the elite

were often better informed than were local colonial officials about

the course

of

events

or

legislation

in

other colonies deemed

detrimental

to

African and/or elite interests. The chain

of

authority within the colonial service led through the governor to

the colonial secretary

in

London; hence British officials rarely

made contact with their counterparts in other British colonies. As

a result, it was the elite, rather than British officials, who kept alive

a sense

of

the unity

of

British West Africa. However, for the

educated elite, the period was one of mounting frustration and

humiliation.

The achievements of their predecessors turned to bitter memor-

ies as hardening racist attitudes led to the exclusion of Africans

404

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH WEST AFRICA, 1905-1914

from senior posts in the colonial service and from official society.

Even the missionary societies, which had educated them in the

faith of oneness before God, now denied them equality within the

church. The colour bar sullied the missionary organisations and

the influence of African clergy waned, though as martyrs their

standing amongst African congregations and their retrospective

image as early 'nationalists' grew. Rejected by the leadership of

white colonial society, some of the African elite reasserted their

cultural roots by adopting African dress and names, along with

a renewed interest in indigenous customs and religion, albeit often

for the purpose of demonstrating the proximity of the latter to

Christian beliefs and practices. The Christian ' Reformed' Ogboni

Society, established among the Yoruba elite in 1914 in response

to the growing European dominance of the Lagos Masonic

Lodge, sought to reinterpret and 'purify' the traditional instit-

ution, a faint glimmer of the syncretism later to become such an

important element of African innovation. However, the psycho-

logical dependence of the westernised elite inhibited their

response. Thus those who broke away from the missionaries to

form their own churches carried with them a respect for

denominational practices and doctrinal orthodoxy. Other African

clergy, such as Bishop James Johnson, could never sever the ties

with the Church Missionary Society; God was still perceived as

dwelling somewhere behind Salisbury Square.

In the older' settled' colonies, African unofficial representatives

appointed by the governor still sat on the legislative council,

ostensibly to advise him. However, such representation provided

no real check on colonial autocracy. The official majority was

required to vote with the governor, who in any case was not

bound by the advice of the council. Thus, in spite of African

unofficial opposition, discriminatory and restrictive legislation

was passed, such as the 1903 Nigerian Newspaper Ordinance and

the 1909 Nigerian Seditious Offences Ordinance, both aimed at

stifling African criticism of the government. In any case, deliber-

ations of the legislative council were normally confined to matters

affecting the 'settled' colony, thus limiting their scope and

effectiveness as an arena for articulating African grievances.

Nevertheless, increased elective African representation on the

legislative councils, as well as African membership of the more

senior policy-formulating executive councils, became major

405

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH WEST AFRICA AND LIBERIA

objectives of the early African nationalists, absorbing much of the

political energies of the educated elite. As in the mission churches,

they clung to a vision of participation in decision-making, though

in

1920

Lugard expressed

the

prevailing British conceit

and

disdain

for

educated Africans when

he

remarked that

'the

interests

of a

large native population shall

not be

subject

to the

will...of a small minority

of

educated

and

Europeanised natives

who have nothing in common with them, and whose interests are

often opposed

to

theirs'.

3

Power remained firmly in European hands. Yet the British were

highly successful

at

incorporating potential African leaders,

giving them

a

stake

in

the colonial system,

a

factor

of

far greater

significance than

the

oft-extolled effects

of the

maxim-gun.

In

Northern Nigeria, the rebellion

at

Satiru

in

1906

by the

Hausa

peasantry posed

as

great

a

threat

to the

Fulani emirs

as to the

British and was duly crushed with combined severity. However,

such isolated incidents need

to be

viewed against

the

general

context

of the

relatively peaceful transition

to

colonial rule

following the initial conquest, coinciding

as it

did with

a

period

of economic boom

in

West Africa between 1906

and the

First

World War.

Both the volume and barter terms of trade improved, resulting

in

an

increase

in the

income terms

of

trade.

4

This

was

most

dramatically illustrated by the growth

of

cocoa exports from

the

Gold Coast. Cocoa

had

been introduced there towards

the end

of the nineteenth century, when

the

leading export was rubber.

In 1902 rubber was overtaken

by

gold, which was mined

in the

western province

by

foreign-owned companies and yielded over

a million pounds' worth

of

exports

in

1907. Gold exports first

exceeded £imin 1907 and

for

most

of

our period were worth

between one-third

and one

half

of

Southern Rhodesia's. From

1910,

however, cocoa took first place

and by 1914

exports

amounted to

5

3,000 tons, worth £2.2m. The Gold Coast was now

the world's largest producer of

cocoa,

and remained so to the end

of

our

period. Nigeria's exports throughout

our

period were

dominated

by

palm produce: between 1905

and

1913 exports

of

palm kernels doubled

in

bulk and their value rose to

£3.1

m,

nearly

3

Report

by Sir F. D.

Lugard

on

the

amalgamation

of

Northern and

Southern

Nigeria, and

administration,

ip/j-rpif (1920), Cmd. 468,

19.

4

See chapter 2,

p. 130.

406

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH WEST AFRICA, I905-I914

half the total. Meanwhile, tin was being mined on the Jos plateau.

Exports began in 1907 and were boosted by the advent of a

railway in 1911; by 1913 they were worth £568,000. In Sierra

Leone, the export value of palm kernels increased threefold

between 1905 and 1913, when it reached £921,000, over two-

thirds of total exports. The expansion of cash-crop production,

if not of mining, enabled growth in African consumer demand.

Nigeria's imports of cotton goods doubled between 1905 and

1913,

while its imports of cigars and cigarettes increased

15-fold. Though the large European import-export firms were

the principal beneficiaries, the African bourgeoisie, the

entrepreneurial and professional classes, as well as the African

primary producer, gained from the better prices for exports and

the increased availability of goods.

The increased revenue from import duties and the bullish

atmosphere of the boom facilitated capital investment and the

expansion of technical departments for forestry, veterinary work

and mineral survey. As a result of the discovery in 1909 of coal

at Udi in eastern Nigeria, the only deposit in West Africa, the

government began construction of

a

railway line to terminate at

a new city, Port Harcourt. Improved transport and communica-

tions,

government propaganda and more coercive pressures such

as forced labour, combined with direct taxation in Northern

Nigeria, further fuelled the expansion of the export sector, albeit

often not as anticipated. In 1911 the main Nigerian railway from

Lagos reached Kano; both government officials and British

commercial interests, particularly the British Cotton Growing

Association, expected it to tap the vast indigenous cotton-

producing areas of central Hausaland. The quest for imperial

sources of raw cotton, as an alternative to dependence upon

American cotton supplies, was a major theme in British colonial

policy. As it turned out, Hausa farmers found that they could reap

a greater return in terms of land and labour inputs by cultivating

groundnuts, a more reliable crop and one that could be eaten in

the event of low producer prices or the failure of subsistence

crops.

As a result, Nigerian groundnut exports jumped from

under 2,000 tons before 1911 to nearly 20,000 tons in 1913.

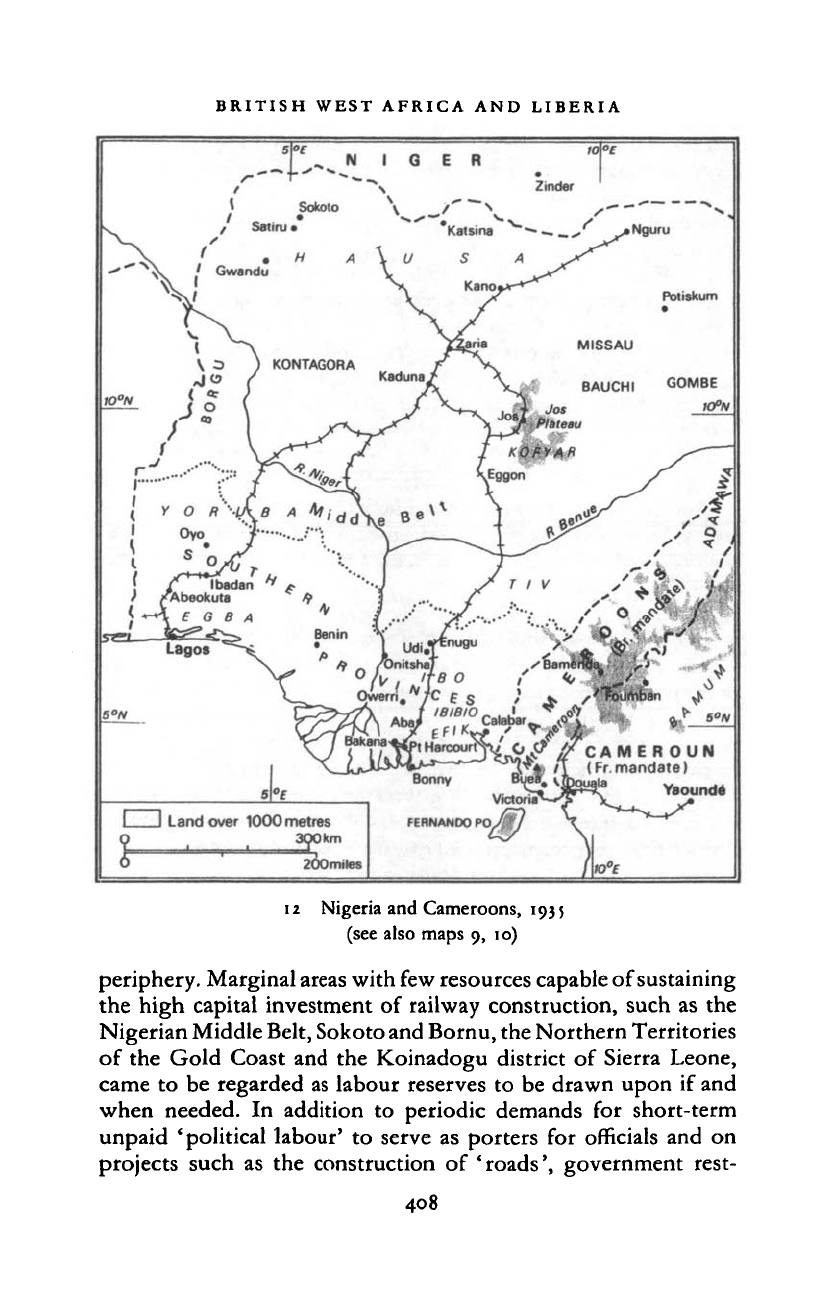

Moreover, railway routes, dictated by strategic considerations

and existing or perceived British marketing opportunities, fav-

oured selected areas while relegating others to the economic

407

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH WEST AFRICA AND LIBERIA

Nguru

Potiskum

CAMEROUN

(Fr. mandate)

I I Land over 1000

metres

O 3O0km

0 ' 200miles

1O°£

12 Nigeria and Cameroons, 1935

(see also maps 9, 10)

periphery. Marginal areas with few resources capable of sustaining

the high capital investment of railway construction, such as the

Nigerian Middle Belt, Sokoto and Bornu, the Northern Territories

of the Gold Coast and the Koinadogu district of Sierra Leone,

came to be regarded as labour reserves to be drawn upon if and

when needed. In addition to periodic demands for short-term

unpaid 'political labour' to serve as porters for officials and on

projects such as the construction of 'roads', government rest-

408

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH WEST AFRICA, 1905-1914

houses and even railways, new migratory labour patterns were

established, occasionally by direct government recruitment for the

commercial sector. In the Northern Territories, chiefs were paid

a head-tax of

5 s

for every man sent to labour underground in the

gold mines of the colony, where the mine companies were in direct

competition with indigenous cocoa cultivators. When such

incentives failed

to

produce 'recruits', district commissioners

resorted to coercion. There was even discussion of implementing

a system based, as in South Africa, on pass-laws, a labour bureau

and

a

revised Master and Servant Ordinance to ensure greater

stability and control over mine labour. Such pressures from

mining interests were ultimately rejected by the Colonial Office

on the pragmatic ground that the burgeoning cocoa industry

might be disrupted. 'The total failure

of

the mining industry

would cause no more, at most, than a temporary set-back to the

revenue of the [Gold Coast] Government. '

5

More often commer-

cial interests and colonial authorities were in direct competition

for African labour. Differential economic opportunities

and

indirect pressures, such

as

taxation, were the primary factors

sustaining

the

level

of

labour supply once

the

pattern

was

established. In general, the areas most distant from the colonial

capitals were also those most neglected by them. They received

little of the limited funds which colonial governments provided

for health or education, and they held little status in the hierarchy

of government postings, though

the

historical and religious

claims of Sokoto and Bornu as centres of Islamic culture and polity

led

to

their rulers exercising

a

measure

of

political influence

disproportionate to these regions' economic significance.

The growth of the colonial economy was accompanied by the

subordination and decline of many indigenous industries: African

salt-producers, for instance, could seldom compete with inexpens-

ive imported salt.

6

Moreover, government policies tended

to

discriminate against African enterprise. While colonial rule facili-

tated Hausa commercial penetration into many hitherto hostile

5

Colonial Office Minute of 24 July 1911, quoted in Roger G. Thomas, 'Forced labour

in British West Africa: the case

of

the Northern Territories

of

the Gold Coast,

1906-1927'', Journal of African History, 1973, 14, 1, 88-9. The same debate took place

in Nigeria in 1911 and had a similar outcome: cf. Bill Freund, Capital and labour in the

Nigerian tin mines (London, 1981).

6

For the persistence of the salt industry at Ada, in the Gold Coast, see Inez B. Sutton,

'The Volta River salt trade', Journal of African History, 1981, 22, 4}-6i.

409

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH WEST AFRICA AND LIBERIA

areas,

Lugard imposed

a

system

of

canoe and caravan tolls

in

Northern Nigeria to reduce the number of people engaged in what

he regarded as 'unproductive' labour, hoping thereby

to

force

them into cash-crop production.

In

1906

he

removed caravan

duties on British cottons and other imports, though not on the

preferred, more durable, indigenous cloth, in order that British

goods might compete more effectively. In 1907 Lugard was posted

to Hong Kong, and his successor, Girouard, rescinded these

measures, but the cloth industry was then hit by the decline

in

cotton production in the main Kano-Zaria region following the

growth of groundnut cultivation. Decreased cotton supplies led

to

a

reduction

in

output and labour requirements, both

in

the

weaving industry and, to a lesser extent, in the dyeing industry,

which survived by utilising imported cloth. On the Jos plateau,

the government upheld European mining leases against the claims

of the indigenous mining and smelting industry. The role

of

Africans

in

mining was reduced

to

that

of

mine labour and

'tributor' sub-contracting: they were compelled

to

purchase

mining 'rights' from European companies

to

work traditional

sites and sell tin to the same companies below market prices. The

inhabitants of mining areas, such as the Birom, lost most of their

land, while timber and water resources were increasingly brought

under the control of expatriate mining interests. It should also be

noted that there were still socio-economies, such as those of the

Fulani pastoralists

and

Kofyar hill-farmers, which were

so

marginal to the colonial system as to be largely unaffected by it.

Those Africans who were able

to

exploit new opportunities

jealously guarded their rights.

As

well

as

recruiting labour,

colonial chiefs often utilised control over the distribution of land

and rights

to

communal labour, recognised under colonial

ordinances, for the cultivation of cash-crops for personal gain. In

the forest regions, traditional rulers leased timber rights

to

contractors who ' mined' the forests, indiscriminately felling trees

to extract selected hardwoods. The colonial governments, despite

conservationist inclinations, had difficulty regulating the timber

industry. The 1902 Southern Nigerian Forestry Ordinance had to

be drastically amended

in

the face of opposition not only from

influential European timber and shipping interests but also from

the traditional leaders and African entrepreneurs, both of whom

viewed government control

as an

infringement

of

indigenous

410

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH WEST AFRICA, I905-1914

rights and as an attack on African economic endeavour. Between

1907 and 1911, similar legislation in the Gold Coast encountered

stiff resistance from the Aborigines' Rights Protection Society,

which was drawn from both chiefs and the educated elite. The

ARPS convened protest meetings, petitioned

the

legislative

council, and sent a delegation to London, including J. E. Casely

Hay ford and E.

J.

P. Brown, barristers who had been active

in

earlier land disputes. As a result, the Colonial Office instituted an

enquiry into land rights and alienation in the Gold Coast in 1912.

Meanwhile the Northern Nigerian Land Ordinance

of

1910,

which was based on Henry George's theories of economic rent,

had aroused considerable interest in Britain, leading to the setting

up by the Colonial Office

of

a West African Lands Committee.

The committee members, predisposed

to a

protectionist policy

based

on the

concept

of

state control

in the

interest

of the

community, were encouraged by the findings

of

the Gold Coast

enquiry. They criticised the exploitation

of

natural resources by

a small elite for personal gain, and the high cost and delays caused

by land litigation, and recommended that control over land

be

removed from the judiciary and be vested in the administration.

This,

however, ignored the political realities of West Africa. News

of the committee had been greeted by

a

storm of protests. Africans

were suspicious

of

British motives and were well aware

of

the

often arbitrary nature of administrative decisions. At

a

meeting

in Lagos, one speaker pointed

to a

recent Sierra Leone land

concession

to

Lever Brothers as

a

portent of the future. Samuel

Pearse,

a

prominent Lagos merchant,

led a

Nigerian protest

delegation

to

London

in

1913.

7

Land 'ownership' was an issue

which united chiefs, the educated urban elite and the emergent

rural capitalist classes. The Colonial Office cautiously shelved the

Lands Committee's recommendations

and the

Gold Coast

legislation was quietly abandoned.

The growing complexity of

the

colonial economy was reflected

in the relations between elites; traditional, educated bourgeoisie

7

Not untypical

of

the multi-faceted British West African elite

of

the period, Pearse

was a leader of the Lagos Aborigines' Protection Society; at various times member of

the legislative council, the Lagos town council, licensing commission and assessment

board; trustee of Lagos town hall and of the Lagos racecourse board of management;

member

of the

diocesan board

and the

parochial board

of

Christ Church,

and

representative of the Anglican church synod. In 1915 he became a Fellow of the Royal

Geographical Society and of the Royal Colonial Institute, London. A. MacMillan, The

red book

ofWtst Africa (London, 1920), 97-8.

411

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008