Roberts A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: from 1905 to 1940

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

At the end of 1933 Kouyate was expelled from the Communist

Party for failing to toe the party line, but he continued to agitate

for African liberation and he collaborated with George Padmore

in trying vainly to organise a Negro World Unity Congress. The

Popular Front helped him to create the French Federation of the

Youth of Black Africa and he presented a plan for decolonisation

to the governor-general in Dakar in 1937. Soon afterwards he

launched the first Association of West African Students, but when

war broke out the Vichy regime deported him and he died in 1942.

Even before this, the approaching war-clouds in Europe had

distracted public attention from anti-colonial politics. Besides, it

was the problem of cultural identity which now most concerned

young black intellectuals in Paris. They realised that France was

only interested in' assimilating' them

as

full citizens insofar

as

they

had adopted Western modes of thought and had rejected ancestral

values.

83

In reaction, they explored the nature of being African:

this was a theme of the magazine Uiitudiant noir, which was

founded in 1934 by Aime Cesaire, a poet from the Antilles, and

Leopold Sedar Senghor from Senegal, who taught in a French

secondary school (and was the first African qualified to do so).

It was they who formulated the concept of

nigritude,

a transitional

form of militancy which was to exert much influence in French

Africa.

CONCLUSION

On the eve of the Second World War, French black Africa found

itself at a crucial stage in its development. On the one hand, it

seemed to be marking time: economic plans had made little

progress, there had been no political reform, social agitation had

collapsed and nationalist claims appeared to have subsided.

Nonetheless, the preconditions for rapid change were all there.

The traumatic experience of the First World War and the

profound upheavals caused by the depression had transformed the

relations of French Africa with the outside world and had

accordingly modified its internal structures. The region was no

longer a more or less negligible dependency of the metropolis;

it was beginning to play a significant role within the Western

capitalist system. The Second World War was to project it into

a new universe.

8j

In 1956 there were only

2,1

j6 black French citizens in French West Africa, apart

from 76,000 in the communes of Senegal who were citizens by birth.

392

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

MADAGASCAR

MADAGASCAR

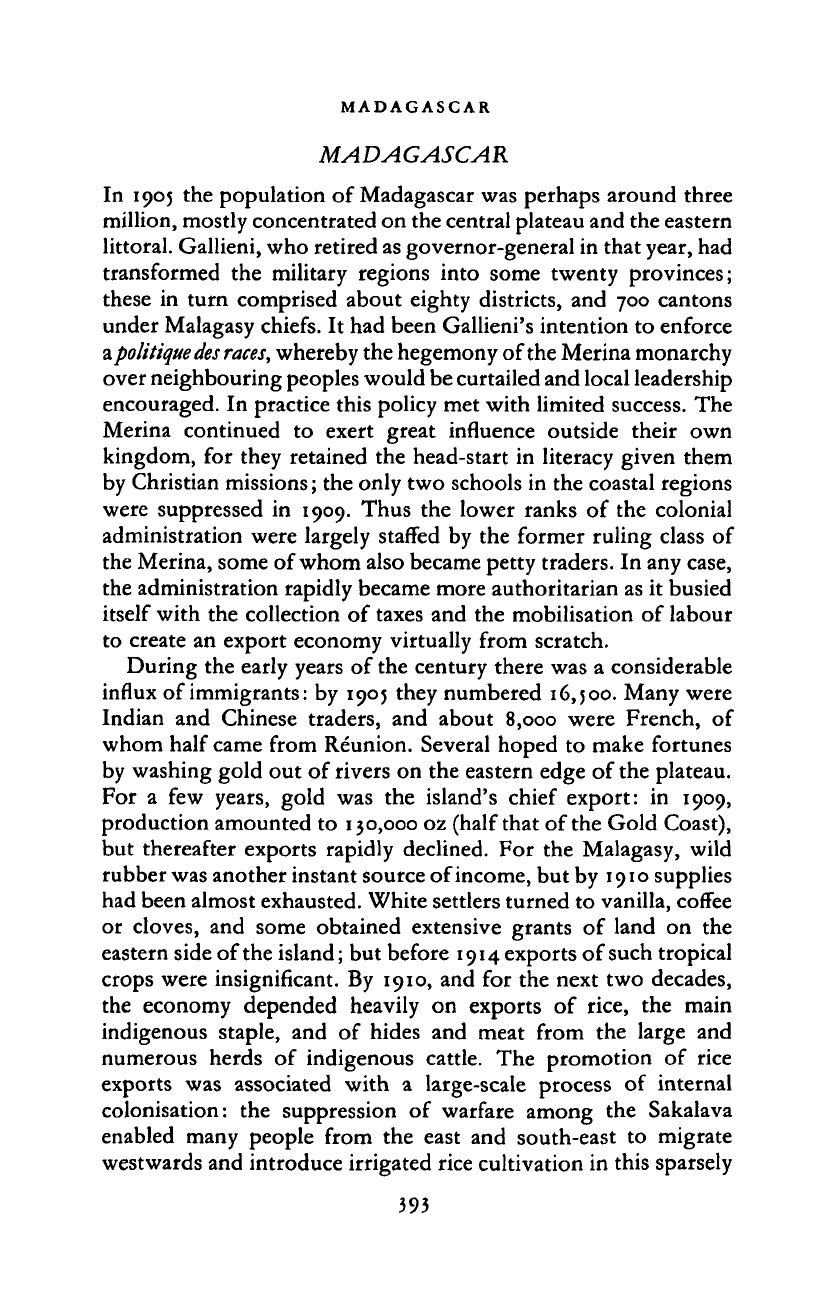

In 1905 the population of Madagascar was perhaps around three

million, mostly concentrated on the central plateau and the eastern

littoral. Gallieni, who retired as governor-general in that year, had

transformed the military regions into some twenty provinces;

these in turn comprised about eighty districts, and 700 cantons

under Malagasy chiefs. It had been Gallieni's intention to enforce

zpolitiquedes

races,

whereby the hegemony of the Merina monarchy

over neighbouring peoples would be curtailed and local leadership

encouraged. In practice this policy met with limited success. The

Merina continued to exert great influence outside their own

kingdom, for they retained the head-start in literacy given them

by Christian missions; the only two schools in the coastal regions

were suppressed in 1909. Thus the lower ranks of the colonial

administration were largely staffed by the former ruling class of

the Merina, some of whom also became petty traders. In any case,

the administration rapidly became more authoritarian as it busied

itself with the collection of taxes and the mobilisation of labour

to create an export economy virtually from scratch.

During the early years of the century there was a considerable

influx of immigrants: by 1905 they numbered 16,500. Many were

Indian and Chinese traders, and about

8,000

were French, of

whom half came from Reunion. Several hoped to make fortunes

by washing gold out of rivers on the eastern edge of the plateau.

For a few years, gold was the island's chief export: in 1909,

production amounted to 130,000 oz (half that of the Gold Coast),

but thereafter exports rapidly declined. For the Malagasy, wild

rubber was another instant source of income, but by 1910 supplies

had been almost exhausted. White settlers turned to vanilla, coffee

or cloves, and some obtained extensive grants of land on the

eastern side of the island; but before 1914 exports of such tropical

crops were insignificant. By 1910, and for the next two decades,

the economy depended heavily on exports of rice, the main

indigenous staple, and of hides and meat from the large and

numerous herds of indigenous cattle. The promotion of rice

exports was associated with a large-scale process of internal

colonisation: the suppression of warfare among the Sakalava

enabled many people from the east and south-east to migrate

westwards and introduce irrigated rice cultivation in this sparsely

393

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

Comoro

Is.

1S»S

20°S

2S°S

4tf>E

SO

°E

Tamatave

t5°S

20 "S

Manakara

2S°S

1

v;

1

1

•'-*

'

Land over

lOOOmetres

0 300km

1

i

200miles

ii Madagascar,

1939

394

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

MADAGASCAR

populated region. The trade in high-bulk commodities gained

greatly from the opening in 1913 of a railway from Tananarive,

the capital, to the port of Tamatave.

However, the country's trade was already firmly under French

control. By 1908 France accounted for nearly 80 per cent of both

imports and exports, and this proportion was sustained

throughout the period. Madagascar, as an isolated and captive

market, paid heavily for its imports, while exports were at the

mercy of monopolistic shipping companies. Customs dues yielded

less than 4 per cent of government revenue between 1905 and

1920;

instead, Malagasy tax-payers were heavily burdened. In

1905 the poll-tax represented 45 days' wages and sometimes

absorbed the whole of a cash income. In 1909-11 the government

began to regroup the population in hamlets of not less than thirty

dwellings, and to suppress shifting slash-and-burn cultivation.

Taxation was frequently levied in the form of labour dues, which

drove many Malagasy into a kind of feudal service with settlers.

Peoples of the south-east, such as the Antesaka, went north in

large numbers to work, first on the railway and then on vanilla

or coffee plantations. And at this early stage in colonial rule, its

benefits, such as they were, were very unevenly spread: outside

Imerina, the provinces contributed on average twice as much to

the budget as they received from it. Even so, the educated Merina

had a particular grievance of their own. They felt especially

threatened by the arrival of Augagneur, governor-general from

1905 to 1910. He was a French politician, a strident republican

and militant freemason, who set himself to curb the influence of

the Christian missions. His offer in 1909 of French citizenship to

those who could pass a stringent test of French culture was

received as an insult by the Merina intelligentsia: they saw it as

a threat to their own new identity as both patriotic and Protestant

Merina. Some radicals, led by a minister of the church, Ravelo-

jaona, looked to Meiji Japan as a source of inspiration. Such

circles engendered in 1913 a secret society, the VVS (Vy Vato

Sakelika), which became the germ of a national movement.

The First World War aggravated the constraints of colonial

rule:

41,000 men served in Europe; 4,000 were killed. The island

was valued by France as a source of cheap rice, manioc, butter

beans (Cape peas), skins and beef extract. The demands of war

also stimulated the production of graphite: 35,000 tonnes were

395

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

exported in 1917 and much was carried to the sea by porters.

Railway construction and other public works were promoted by

the technocratic governor-general Garbit

(1914—17,

1920-24): by

1923 there were lines between Tananarive and Antsirabe, and

between Moramanga and Lake Alaotra. These were built with

forced labour, which was also applied during these years to

plantations of coffee and vanilla; in addition to their own

employees, settlers were provided by government with workers

fulfilling the obligation to perform

30

days of paid labour per year.

Between

1914

and

1921

prices rose fivefold while cash wages were

only doubled; yet in

1919

the poll-tax was increased by two-thirds.

There were still other burdens: in 1917-18 the island was afflicted

by a severe drought, and in 1919 influenza killed over 100,000

people. In places, social tension became acute. In 1915-18 there

was unrest among the pastoral peoples of the south-west, the

Antandroy, Bara and Mahafaly; ironically, this was facilitated by

the government's campaign to reduce the powers of local

dynasties. And at the end of 1915 the government was alarmed

by rumours of a conspiracy by the VVS, several of whom were

arrested and heavily sentenced, though they were released in 1918.

This incident reflected the government's concern to appease the

fears of settlers whose economic importance had been enhanced

by the war. For some years they had used the virulent local press

to call for a share in government. In 1921 a conference of the

Delegations Economiques et Financieres was convened, and in

1924 this became a consultative assembly in which settlers

regularly attacked the cost of government. They failed to obtain

any legislative power, but they continued to benefit from laws on

land and labour.

Under Governor-General Olivier (1924-30), the administration

began to move away from its earlier reliance on settlers as the

mainstay of the economy; their incipient feudalism was overlaid

by the more or less enlightened despotism of a government which

assumed the main role in organising production. The mobilisation

of labour remained a high priority, but investments were now

made in improving its strength and skills. In 1926 forced labour

service for public works was introduced; this was partly applied

to the building of a railway from Fianarantsoa to the coast, but

also to extending the network of motorable roads, which between

1925 and 1933 increased from 2,400 km to 14,500 km. This

396

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

MADAGASCAR

simplified administration; it also extended the potential area of

small-scale cash-crop production. The health services were ex-

panded and the population, hitherto static or in decline, began to

increase, though plague was a serious worry in the 1920s and was

not brought under control until 1937. Government commitment

to primary education, which had begun with Gallieni, persisted.

By 1930 there were more children in state primary schools than

in those of the missions, and about a quarter of the relevant

age-group

was

in

school:

a

much higher proportion than anywhere

in French-speaking black Africa. Malagasy was now accepted as

the medium of primary-school instruction. A school in Tananarive

trained students for entry to the medical school and the lower

ranks of the civil service. The administration of justice gave

greater scope for Malagasy customary law, while from 1927 tax

was assessed on property and products rather than persons.

There were however no political concessions. True, local

councils of notables chose representatives for the Delegations

Economiques et Financieres, but these Malagasy members met

separately from the Europeans and were quite ineffective. In

theory, of

course,

French naturalisation was a possible avenue to

political rights; in practice, the door was closed, if only because

the requisite education was virtually unavailable. And it was the

acquisition of French citizenship which became the chief goal of

Madagascar's first real nationalist movement. This was initiated

by Ralaimongo (18 8 3-1942), a Betsileo and former Protestant

teacher who had served in France during the war and stayed on

there, making contact with socialists. Back in Madagascar, he

founded in 1923 a French-language newspaper, for political

discussion in Malagasy was forbidden. The paper attacked colonial

abuses, encouraged passive resistance among plantation workers,

and demanded both mass naturalisation and Madagascar's trans-

formation into a French

departement.

Ralaimongo's followers were

a small but motley group, including former members of the VVS,

a Creole settler and two French Communists. In May 1929 they

mounted a demonstration in Tananarive; Ralaimongo was placed

under house arrest and others were imprisoned.

When the world-wide economic depression struck in 1930, the

island's economy was already in difficulties. Prices for graphite

and vanilla fell by 50 per cent in 1927-8: in 1929, vanilla exports

exceeded world consumption. Between 1926 and 1934 cyclones

397

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

devastated plantations

on the

east coast. Many settlers were

brought near ruin and could not repay loans from the government.

To rescue settlers, Governor-General Cayla (1930—9) persuaded

the French government to add bonuses to depressed export prices,

but this also encouraged Malagasy production which was further

fostered

by

government propaganda.

In

1934 the government

reckoned that the costs of the Malagasy producer were half those

of the settler. By 1935 Malagasy producers occupied more than

two-thirds of the area under cash-crops such as coffee, cloves and

vanilla. It was largely due to Malagasy planters that in the course

of the 1930s coffee became the island's chief export: by 1938

it

contributed 36 per cent

of

the total value

of

exports and

the

quantity,

at

41,000 tonnes, was close

to

that exported from

Uganda, Kenya and Tanganyika combined. Clove production also

rose sharply: 6,000 tonnes were exported

in

1938, compared

to

8,000

from Zanzibar. Thus among the peoples along the eastern

littoral dependence on migrant wage-labour was diminished, and

some were able

to

register title

to

land, under

a

scheme begun

in 1929. The basis for

a

rural middle class was being laid. Yet

political ambitions seemed

no

nearer fulfilment.

In

1936

the

advent

of

the Popular Front government

in

France led

to

the

release

of

demonstrators gaoled

in

1929, while

a

strike

in

Tananarive (now a town of 140,000 inhabitants) was rewarded by

the tentative recognition of trade-union rights for Malagasy.

In

1938 access to French citizenship was slightly eased, but in 1939

it was enjoyed by

less

than

8,000

Malagasy.

National independence,

not assimilation, was now

the

prevailing ambition

of

literate

Malagasy, though the unification

of

the country by

a

dynamic

bourgeoisie, on a foundation of nationalism and modernism, was

still

a

distant objective.

398

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

8

BRITISH WEST AFRICA AND LIBERIA

This chapter is concerned with those parts

of

West Africa where

by 1918 English

was

established

as the

principal language

of

government. They included

the

independent black republic

of

Liberia, the British possessions

of

the Gambia, Sierra Leone,

the

Gold Coast and Nigeria, and sections

of

the mandated territories

of the former German Kamerun and Togo which were adminis-

tratively attached

to

Nigeria

and the

Gold Coast, respectively,

following the First World War. Varying in size from the Gambia,

its 4,003 square miles drawn out along the Gambia river for three

hundred miles,

to

Nigeria, which covered over 356,000 square

miles,

they encompassed

a

diversity

of

ecological zones: coastal

swamps, tropical rainforests, savanna, sahel, montane and riverain

regions. These contrasts

had

fostered long-established internal

commerce and export trade, sustained in turn by some of the most

populous areas

in

tropical Africa.

The

pre-colonial political

institutions

in

what became anglophone West Africa had ranged

from ancient forest kingdoms and Islamic theocracies to a variety

of stateless societies.

By

1905 they

had

been incorporated

in a

number

of

colonial polities which were themselves

far

from

homogeneous.

The British West African possessions were constitutionally

rather untidy ' multiple dependencies', consisting of older coastal

'settled' colonies linked to larger hinterland protectorates.

In

the

former

the

African population were British subjects

and

were

entitled to various legal rights not enjoyed by 'protected persons'

in the latter. This was further complicated

in

the Gold Coast

by

a tripartite linking

of

the ' settled' coastal colony, beyond which

lay Ashanti (Asante),

a

colony

by

conquest,

and the

hinterland

protectorate

of

the Northern Territories, each separately admin-

istered under

the

governor, while three British administrators

were

in

charge

of the

protectorate

of

Northern Nigeria,

the

protectorate

of

Southern Nigeria,

and the

' settled' colony

and

399

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH WEST AFRICA AND LIBERIA

protectorate of Lagos. The German colonies were moving from

an era of rather muddled imperial supervision and scandal to that

of so-called 'scientific' colonialism and exploitation. In Liberia,

the non-indigenous Americo-Liberian ruling class struggled to

maintain sovereignty over a country it barely governed against

the threats of encroachment by its erstwhile European allies.

Economically much of the region was already integrated into

the Western commercial system. While subsistence production

remained an important aspect of the domestic economy, West

Africans had demonstrated a willingness to respond to market

incentives. As a result, there was a securely established European

maritime trade based on African small-scale production of export

commodities and natural products. Hence entrenched European

trading firms mounted a strong and sustained opposition to the

competing demands of expatriate mining and plantation interests.

While often locally significant, the plantation and mining sectors

never predominated in anglophone West Africa as they did

elsewhere in colonial Africa. Colonial economic

policies,

monetary

regulations and infrastructural developments in communications,

transport and distributive systems facilitated the extension of the

existing commercial systems into new areas. On the other hand,

despite elements of continuity, by subordinating the internal

domestic economy to the interest of the export sector while

subordinating the latter to external influences, the ' open' colonial

economy represented a fundamental change in the nature of

Afro-European relations.

Differences in colonial legislation, geography, indigenous cult-

ure and socio-economic opportunities influenced the nature and

tempo of local response to the colonial situation. Yet the African

population shared a core of experience derived from the not

dissimilar nature of German, British West African and Americo-

Liberian colonialism. All three adopted paternalistic policies of

indirect native administration; facilitated the expansion of Western

law and education and Christian missions; opened the economy

to foreign exploitation; and sought to justify their economic and

political control on the bases of racial and cultural superiority. The

very nature of indigenous political institutions was altered in the

process of being incorporated into the fabric of colonial

administration. The adoption of cash-crops, and especially long-

term investment in tree-crops such as cocoa, was giving rise to

400

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH WEST AFRICA AND LIBERIA

new attitudes towards

the

ownership

and

sale

of

land,

the

emergence

of

a

rural capitalist class dependent upon

the

vagaries

of the world market,

and

increasing reliance upon food imports;

there were also subsidiary effects such

as the

decline

in

nutrient

intake resulting from

the

increased

use of

cassava. Areas

of

economic growth such

as

the cities of Lagos, Freetown and Accra,

the Gold Coast cocoa-growing region

of

Akwapim

and the

German plantations

on Mt

Cameroun were the foci

of

migration,

leading

to the

disruption

of

indigenous institutions

and

culture.

Greater mobility

and

wider social intercourse also facilitated

the

spread

of

social

and

epidemic disease, such

as

syphilis

and

gonorrhoea, smallpox

and

sleeping-sickness. Public health servi-

ces provided little defence, for

as

yet they devoted the bulk of their

resources

to the

care

of

Europeans

and the

urban elite.

The burgeoning African

elite,

their status based on educational,

economic

and

social achievement, with their self-conscious class

identity, English

as a

common language and wide-ranging contacts

which

cut

across

the

narrow confines

of

ethnic

and

colonial

political divisions, were already

a

conspicuous element

in

West

African society. Confronted with mounting European racism,

they were becoming increasingly assertive

in

their demands

for

participation

in the

decision-making process

and for

recognition

as spokesmen

of

the new order. Though often

as

remiss

as

many

of

the

traditional leaders when

it

came

to

articulating

the

grievances

and

aspirations

of the

common people, they were

nevertheless

to

foster a new nationalist, and often radical, political

consciousness. Meanwhile, indigenous cultural practices

and

belief systems were strained

by

new problems

and

environments.

Many

of

the coastal areas

of

anglophone West Africa

had

been

exposed

to

generations of sustained Christian missionary activity.

The more concrete mode

of

thought prominent

in

pre-scientific

African supernatural empiricism

1

was

confronted

by an

abstract

and analytical Western mode, though Christian missionary teach-

ings frequently blurred

the

distinction

and

linked Christian faith

with Western material culture.

In

such circumstances,

the

initial

response

to

missionary Christianity was often followed

by

frust-

ration

and

rejection

as the new

religion proved inadequate

as a

system

of

explanation, prediction

and

control.

1

Cf.

Robin Horton, 'African traditional thought and western science', Africa,

1967,

37,

I-I;

idem.,

'African conversion', Africa, 1971, 41,

2.

401

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008