Roberts A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: from 1905 to 1940

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MOZAMBIQUE

interest.

It

was opened

in

1923

but

carried little local traffic

and

barely covered its working

costs.

A railway alone could not ensure

economic growth,

and the

necessary investment was lacking.

In

1922-3,

Smuts contrived

to

thwart efforts

to

raise loans

for

Mozambique, since

any

expansion

of

its

own

production would

undermine South Africa's ease of access to its labour. And in

1922

Smuts sought to renegotiate the 1909 convention which regulated

this labour supply. He wished

to

control the railway

to

Lourenco

Marques

and the

port

itself,

and to

these ends

was

prepared

to

block completion

of

the Benguela railway

in

Angola

and

call

on

Britain

to

send a warship

to

Lourenco Marques. The negotiations

failed, the convention lapsed

and in

1924 Smuts fell from power.

All the same, Mozambique could not manage without its invisible

earnings from South Africa,

and its men

were still willing

to go

there,

if

only

to

avoid forced labour

at

home.

Once

in

retirement, Brito Camacho deplored

the

economic

incompetence

of the

Portuguese government

in

Mozambique:

' To civilise,

for the

state, means keeping

the

heathen

in

submis-

sion, prompt

in

paying ever-rising taxes,

and

well-disposed

towards military service.'

He was

scathing about

the

lack

of

expertise — the bachelor of theology who managed one company

and

the

poet

who had

been sent

to

study cotton-growing;

he

complained that

in

1921-2

the

Lourenco Marques area actually

imported rice, oranges

and

other foodstuffs which could easily

have been produced locally.

He

pointed also

to the

economic

stagnation caused

by the

pursuit

of

the illusion

of

cheap labour:

The whites have pledged themselves not to create needs in the blacks, the need

to clothe themselves, the need to feed themselves, the need to house

themselves...in the certainty that once these needs have been created, wages

could not remain what they have been, misery and exploitation pretending to

be payment.'

In 1922 the situation was described by the British vice-consul at

Porto Amelia:

Throughout this country

a

system

of

compulsory labour

is in

force. Some

employers manage

so

far as possible to get their work done

by

voluntary labour

for which they

pay

reasonably good wages.

But in the

vast majority

of

cases

they simply send

in an

application

to the

local Portuguese authority

for a

specified number

of

labourers

and he

supplies this number

or

less, according

to

the

circumstances,

at a low

rate

of

wages.

10

* Brito Camacho,

Mozambique:

problemas coloniais

(Lisbon, 1926),

40, 46, 47, 56.

10

Hall-Hall

to

Foreign Office,

IJ

April 1922,

FO

371/8577.

513

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PORTUGUESE AFRICA

The vice-consul went on to explain that the high commissioner,

Brito Camacho, was determined to put an end

to

this situation;

yet he had himself contracted to supply the British-owned Sena

Sugar Estates with 3,000 men from Quelimane district. Against

this background

it is

easy enough

to

explain

the

continued

attractions of seeking work in Southern Rhodesia or South Africa.

The demand

for

labour within Mozambique was accelerated

not only by the military campaigns in 1916-18 but by price-rises

for tropical products. Sisal had been planted in some coastal areas

by 1914,

but

wartime and post-war needs encouraged further

planting;

by

the late 1920s

it

was grown along the coast near

Inhambane,

in

Mozambique district

and in

Niassa Company

territory,

and

inland

on the

lower Zambezi.

In

Mozambique

Company territory, sugar continued to be the economic mainstay.

The post-war commodity boom boosted

the

value

of

sugar

exports, and in 1922 the company's total exports exceeded those

from the Colony. By this time, sugar-production was in the hands

of only two companies, which had become virtually self-governing

states:

the Companhia Colonial de Buzi and Sena Sugar Estates.

From 1920, sugar producers had

to

deposit 10 per cent of their

crop

in

Mozambique (where much was made into cheap liquor)

and sell 75 per cent of the remainder to Portugal, which by 1928

received three-quarters

of

its sugar needs from the empire.

In

1924,

out

of

100,000 contract workers in Mozambique Company

territory, one-third were

in the

sugar industry. Sugar was,

however, a shaky foundation. Prices fell in 1925; there were also

disastrous floods, and by 1926 the company's exports were worth

only one-fifth of those from the Colony. In that year total exports

from Mozambique were worth /[2.6m and the main contributor

was not a plantation crop at all but African-grown groundnuts, of

which exports increased fourfold in bulk between 1914 and 1928.

As

for the

Niassa Company's territory, conditions there

remained as bad as ever.

It

suffered more than any other part of

Mozambique from the war, which may have caused more than

50,000 deaths in the region: forced labour and food requisitions

facilitated the spread of disease, especially the influenza pandemic

of 1918, while there was a severe drought in 1919. Ironically, the

war also caused the territory to become

a

British responsibility:

in 1917 Smuts persuaded

the

British government

to

seize

the

German majority shareholding in the Niassa Company, in order

5H

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

MOZAMBIQUE

to complete the extinction of German control along the east coast.

And since Britain had helped to finance the Portuguese war effort,

it was able to override Portugal's wish to cancel the company's

charter; instead, the confiscated shares were sold in 1918 to Sir

Owen Phillips, chairman of the Union Castle shipping line. The

Phillips regime brought no relief to the company's subjects. In

1919 it launched a campaign against the Makonde, who held out

on the plateau until 1922. Men were rounded up for work in the

Zambezi sugar-fields, and also on local cotton, coconut or sisal

plantations. As in the Colony, administrative officials were grossly

underpaid and most engaged in trade or in running plantations,

despite attempts to prevent this. Yet European production was

virtually negligible. The territory's total exports in 1926 were

worth only £115,000, and of these three-quarters consisted of

African crop surpluses. Nonetheless, Phillips (who became Lord

Kylsant in 1923) refused to invest more money in the Niassa

Company unless its charter was extended, and this Portugal

refused to do. Customs revenue continued to be negligible, and

the company paid its way only by increasing African tax-rates

almost annually between 1920 and 1927, when it was reckoned

that after paying tax the people of Niassa were left with sixpence

per head per year. In real terms (allowing for inflation), the rate

of tax at first declined but then rose very sharply. Revenue rose

in real terms, but the number of tax-payers declined. Portuguese

officials and their African assistants resorted to hideous cruelties

in order to enforce payment. Flogging, rape and murder increased

the stream of emigration into British territory: between 1921 and

1931 more than 100,000 Yao and Makua may have fled to

Nyasaland while many thousands of Makonde took refuge in

Tanganyika.

1926—1940

The collapse of the Portuguese Republic in 1926 brought no

immediate change in the affairs of Mozambique. In 1927 the South

African government and mining industry contrived to prevent

Portugal from raising a £1201 loan for its overseas territories.

Thus it was clearer than ever that Mozambique would have to

continue to depend heavily on its export of labour to South Africa.

Salazar, more concerned to balance budgets than foster growth,

515

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PORTUGUESE AFRICA

was therefore eager to negotiate

a

new labour convention while

Hertzog,

the

South African premier, was less grasping than

Smuts. The convention signed in May 1928 exchanged a guaran-

teed tonnage of South African freight through Lourenco Marques

for certain restrictions

on

recruitment

in

Mozambique. Such

labour was

to

be used only on the Transvaal mines; the annual

maximum total was to be progressively reduced from 100,000 in

1929 to 80,000 in

1933;

the initial contract was limited to one year

and

the

maximum period

of

continuous service

to

eighteen

months.

In

another sphere, however, Salazar finally asserted

Portuguese independence: he resisted all attempts by the British

Foreign Office

to

extend the charter of the Niassa Company.

It

was duly wound up in 1929, without having once paid a dividend.

In 1930, Salazar's Colonial Act obliged the Zambezi concess-

ionaires

to

surrender their pra^ps, thus losing their police and

administrative functions

and

their rights over African labour.

Meanwhile, Salazar allowed work to continue on a new railway,

crossing Mozambique district from the coast towards Lake Nyasa

(Malawi):

by

1929

it

had reached Nampula, less than

a

third of

the way.

The first impact of Salazar's regime was soon followed by that

of the world-wide depression

in

1930. This severely damaged

Mozambique's transit trade, which was now worth three times as

much as domestic trade and was largely sustained by exports from

the Rhodesias and Katanga. As elsewhere in Africa, the depression

prompted great efforts to offset falling prices by increasing output;

as elsewhere this involved much coercion

of

labour.

(In

1928

unpaid labour for the government had been abolished, but in view

of prevailing wage-rates this was not an impressive reform.)

In

1932 the value of domestic exports from Mozambique was only

two-thirds what

it

had been

in

1929 (which in terms of sterling

was £3.1111). Yet the value

of

exports would have fallen much

further had not their quantities sharply increased. This was mainly

due to the mobilisation of labour in Quelimane and Mozambique

districts, which comprised half the total population; by 1933 they

contributed

70 per

cent

of

crop exports from

the

whole

of

Mozambique. By 1936, when prices had begun

to

recover, sisal

exports from the colony had increased fourfold in bulk since 1928;

sisal now comprised one-fifth of Mozambique's exports. The price

of sugar had fallen more steeply, and

it

contributed only 12 per

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

MOZAMBIQUE

cent, even though production in the Colony had been much

expanded and was now double that in Mozambique Company

territory. Altogether, plantation produce made up 36 per cent of

total exports. The rest consisted very largely of crops grown or

gathered by Africans: groundnuts (the main export) formed

almost one-quarter of the total in 1936; much copra was

produced by African squatters on coastal concessions, while

cashew nuts were grown to meet a rising demand in India.

Meanwhile, the links with South Africa and British central

Africa were strengthened. In 1929 Britain had arranged for a

railway bridge to be built across the Zambezi at Sena, to link the

Trans-Zambezia railway to the line from Nyasaland; it was

opened in 1935. As the economies of southern Africa recovered

from the depression, so their need for labour revived. By 1934,

many Africans from Mozambique found seasonal work in Nyasa-

land, with African cotton-growers as well as white tea-planters

(who by 1940 employed about

5,000

such migrants). In 1934,

Southern Rhodesia renewed the agreement of 1913; recruitment

was held at 15,000 per year, but after 1936 it was extended outside

Tete district, while many men found their own way over the

frontier; between 1936 and 1941 the number of African workers

from Portuguese territory in Southern Rhodesia rose from 25,000

to 46,000. The labour convention with South Africa was revised

in 1934 to allow men from Mozambique to be used by sugar-

planters in Zululand as well as in the Transvaal mines. In 1936

the annual maximum for recruitment was raised to 90,000 and in

1940 to 106,000. However, when in 1936 WNLA began again to

recruit north of latitude 22°S, this did not directly apply to

Mozambique, where the Sabi river remained the northern boun-

dary of recruiting, though many men from the north crossed into

Nyasaland to sign on for the Rand.

The continued restriction of WNLA recruiting to the far south

reflected the rising demand for labour within Mozambique. This

was due partly to increased harbour traffic and public works. The

road system, much enlarged in the 1920s, required extensive

maintenance, while new railways were under construction. In the

north, the line from Mozambique advanced slowly west into

productive agricultural country; in the far south, a spur from the

Transvaal line was extended in

193 5

to serve

a

projected irrigation

scheme in the Limpopo valley. In 1938 work began on a line from

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PORTUGUESE AFRICA

the Zambezi bridge towards Tete, with a view to exploiting the

Moatise coalfield. By this time, however, labour was wanted

above all for growing cotton. The promotion of cotton-growing

had for some years been one aim of Portuguese colonial policy.

The expansion of Portugal's textile industry in the early years of

the century had been supplied mainly from outside its empire. In

an attempt to reduce this drain of foreign exchange, the military

government introduced in 1926 a decree designed to boost

cotton-production in the colonies. Zones were specified within

which Africans could discharge labour obligations by growing

cotton, while the right to buy, process and market cotton would

be leased to companies. This scheme only began to make progress

after

1933,

when a minimum price for cotton was introduced, and

the main impetus came in 1938 when a Cotton Export Board was

set up to provide seed, train experts and conduct research.

Between 1935 and 1940 cotton output in Mozambique, mostly

from the northern districts, rose from 2,300 tons to 19,000 tons,

for which Portugal paid 30 per cent below the world price. The

advent of war intensified the drive to produce cotton, which on

the lower Zambezi caused the extortion of forced labour from

women at the expense of their own food supplies. Intolerable

conditions continued to drive many people from northern Moza-

mbique to settle in Nyasaland, especially Mlanje district; even

though the British discouraged this in the 1930s, it is likely that

in the course of the decade there were at least 50,000 such

migrants.

11

By 1940 the pressure to produce for export had placed great

strain on traditional farming methods and the ecological balance

of even the most fertile regions. The concession companies could

all command contract labour in generous quantities. As a result

they tended to increase output by essentially labour-intensive

methods. There was little technical advance and Mozambique

became a producer of primary products, many of which, like

cashew nuts, had to be sent abroad even for preliminary proces-

sing. Factories existed to make fireworks, perfume, bus bodies,

ice,

tin cans, lime, soap and furniture, and to process maize, tea,

" This estimate is based on figures for total immigrants resident in Nyasaland in 1931

and 1945, allowing for an element of natural increase: cf. R. R. Kuczynski,

Demographic

survey of the British colonial

empire,

II (London, 1949),

5

37—9.

518

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

MOZAMBIQUE

tobacco and sugar. With the exception of sugar, this odd

assortment of industries scarcely constituted a sound industrial

base.

Hundreds of thousands of men and women were compelled to

work for abysmal wages. Few, however, had developed any sense

of common identity as workers. While many men must have spent

several years, on and off, in the mines of the Transvaal, most of

those who returned were tied to rural communities which had

been maintained by the women they had had to leave behind;

indeed, in the south the role of women in local leadership

markedly increased. Officials feared that returning migrants might

have been infected with Protestantism or 'Garveyism', and they

certainly founded a great many independent churches. The more

responsible jobs open to Africans tended to go to immigrants

from Nyasaland, of whom there may have been 3,000 in 1935,

including foremen on sugar estates and also clerks. It was the

dockworkers of Lourenco Marques who protested most consist-

ently: they struck seven times in

1918-21,

and struck again in the

1920s and 1930s.

The formal aspects of European civilisation were slow to make

any impact on Mozambique. During the 1930s the resident white

population increased by a

half,

but in 1940 numbered only 27,000;

there were about an equal number of Indians, Chinese and

mestizos,

most of whom lived in Beira and Lourenco Marques. By contrast,

the total population may have been as much as five million.

Education began to make some progress after the First World

War. A state system was devised to provide free and compulsory

instruction for all African children under twelve, leading to

technical training at secondary level. European children had the

opportunity to go on to the

liceu

which was opened in Lourenco

Marques in 1918. A parallel course was offered by mission schools

but they too had to teach in Portuguese and, after 1935, state aid

was granted only to Catholic missions. In J931 there were

officially 210 state and 254 missionary schools with a combined

total of 53,394 pupils. These figures include European children

and show that even one year in school was still a rare experience

for an African child. The

liceu

had 479 pupils, three of whom were

African. The same set of statistics reveals one high-quality

hospital in Lourenco Marques, 22 other hospitals and 51 clinics.

5*9

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PORTUGUESE AFRICA

For

the

vast majority

of the

African population, health

and

education facilities

in

1940 were

no

more

and no

less than they

had been before

the

Portuguese arrival.

As

to

what Africans thought

and

said about their condition,

we have

few

clues other than their

own

actions. There

had for

some time been printed protests among

the few

literate

mestizos

and Africans

in

Lourenco Marques.

In

1918 they

had

founded

a

newspaper called

O

Brado Africano

('

The African Cry') and in 19

3 2

this boldly announced,'

We

no longer want to suffer the bottomless

pit of your excellent colonial administration...We have the scalpel

ready.'

12

But

this outlet

for

subversive thought

was

soon shut,

and

the

best evidence

for

popular African opinion

in

these years

seems

to be

the mordant songs

of

the Chopi,

in

the

far

south, and

of the plantation workers

on the

Zambezi.

13

ANGOLA

In some ways, Angola

had

much

in

common with Mozambique

at

the

beginning

of

the twentieth century. Ancient seaports were

connected

by

long-established trade routes

to the

peoples

of

the

inland plateau;

the

Portuguese provided commercial links

to the

outside world but their effective rule was confined to

a

few trading

stations. However, there were also important differences.

In

south-east Africa the plateau

had

mostly been taken over

by the

British, whereas

in

Angola virtually

the

whole length

of the

historic trade routes was reserved

to the

Portuguese.

In the

long

run, this fact was

to

prove an asset

to

the Portuguese;

in

the short

run,

it was a

grave liability.

For in

Angola,

in

contrast

to

Mozambique, population was densest in inland areas

far

removed

from Portuguese settlements

in

coastal towns

and

river valleys;

transport problems rendered these inland areas hard

to

control

and inhibited economic expansion. Nor did Angola, at this period,

have Mozambique's advantage

of

providing

an

outlet

for

mines

in

the

interior, which had stimulated the construction

of

railways

and harbours

and

provided

the

territory with

an

income from

transit traffic

as

well as migrant labour. Thus Angola's economy

grew even more slowly than that

of

Mozambique, though

at

least

12

Quoted

by

James Duffy,

Portuguese

Africa (Cambridge, Mass., 1959), 305-6.

13

See

chapter

5,

pp.

247-8.

520

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ANGOLA

Angola's lack of invisible earnings obliged the Portuguese there

to pay closer attention to the country's own material resources.

ipoj—1920

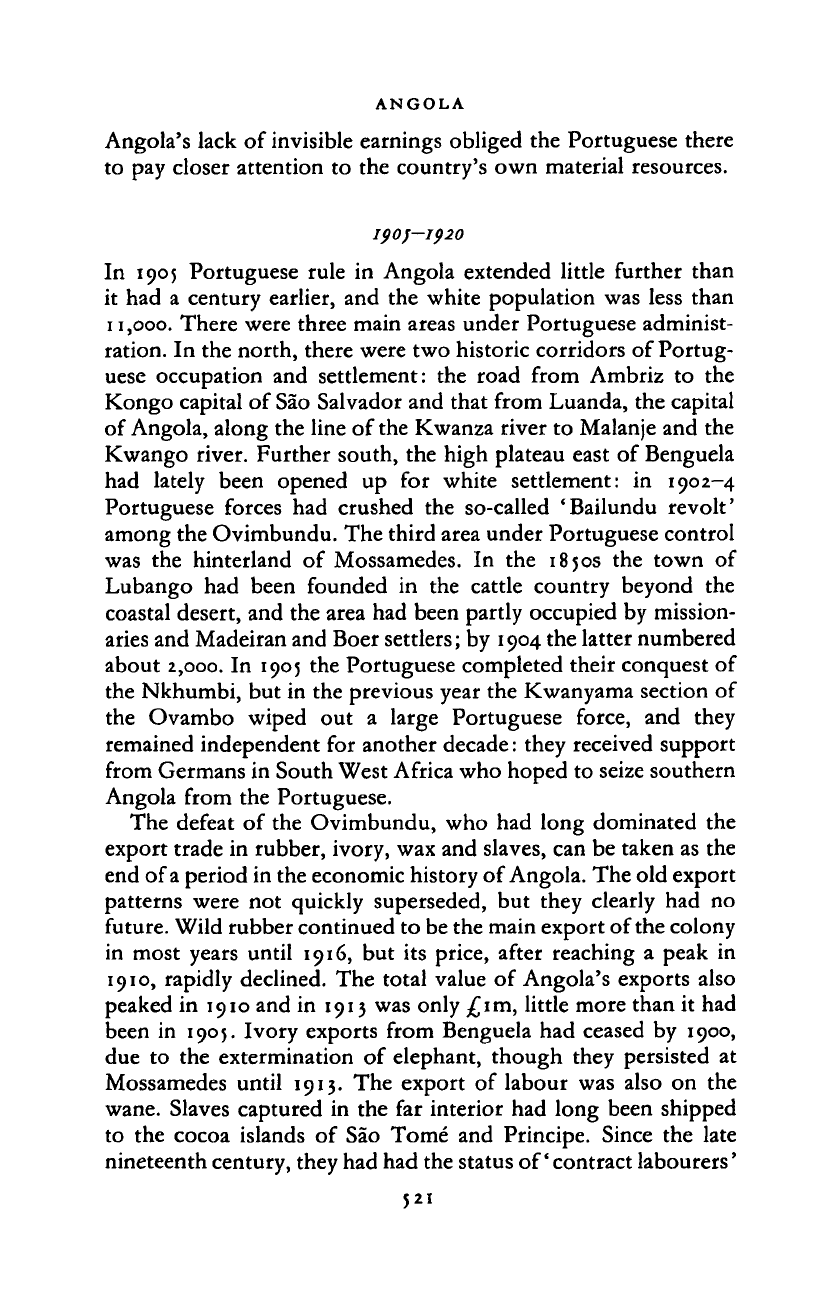

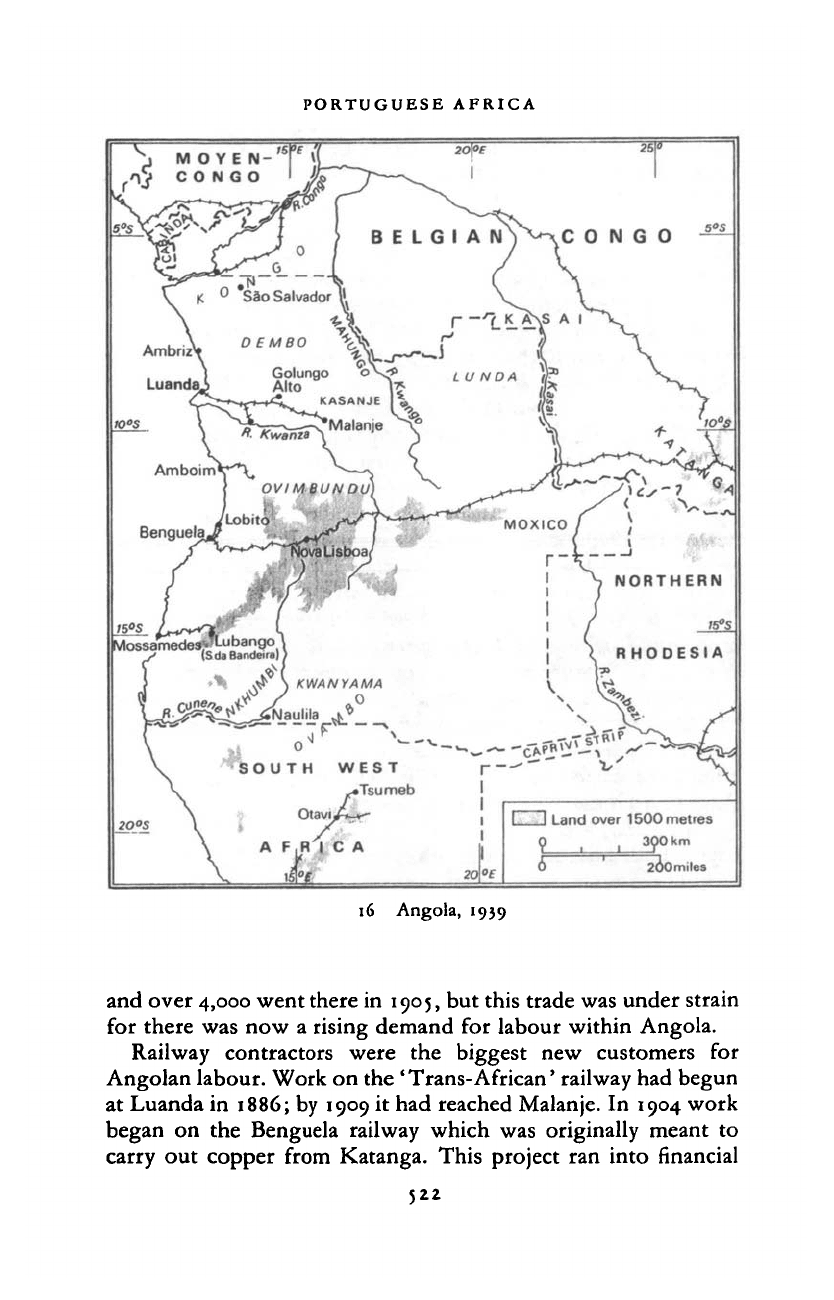

In 1905 Portuguese rule in Angola extended little further than

it had a century earlier, and the white population was less than

11,000. There were three main areas under Portuguese administ-

ration. In the north, there were two historic corridors of Portug-

uese occupation and settlement: the road from Ambriz to the

Kongo capital of Sao Salvador and that from Luanda, the capital

of Angola, along the line of the Kwanza river to Malanje and the

Kwango river. Further south, the high plateau east of Benguela

had lately been opened up for white settlement: in 1902-4

Portuguese forces had crushed the so-called 'Bailundu revolt'

among the Ovimbundu. The third area under Portuguese control

was the hinterland of Mossamedes. In the 1850s the town of

Lubango had been founded in the cattle country beyond the

coastal desert, and the area had been partly occupied by mission-

aries and Madeiran and Boer settlers; by 1904 the latter numbered

about 2,000. In 1905 the Portuguese completed their conquest of

the Nkhumbi, but in the previous year the Kwanyama section of

the Ovambo wiped out a large Portuguese force, and they

remained independent for another decade: they received support

from Germans in South West Africa who hoped to seize southern

Angola from the Portuguese.

The defeat of the Ovimbundu, who had long dominated the

export trade in rubber, ivory, wax and slaves, can be taken as the

end of a period in the economic history of Angola. The old export

patterns were not quickly superseded, but they clearly had no

future. Wild rubber continued to be the main export of the colony

in most years until 1916, but its price, after reaching a peak in

1910,

rapidly declined. The total value of Angola's exports also

peaked in 1910 and in 1913 was only £im, little more than it had

been in 1905. Ivory exports from Benguela had ceased by 1900,

due to the extermination of elephant, though they persisted at

Mossamedes until 1913. The export of labour was also on the

wane. Slaves captured in the far interior had long been shipped

to the cocoa islands of Sao Tome and Principe. Since the late

nineteenth century, they had had the status of' contract labourers'

521

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PORTUGUESE AFRICA

0

N G 0

390 km

200miles

16

Angola, 1939

and over 4,000 went there in 1905, but this trade was under strain

for there was now

a

rising demand

for

labour within Angola.

Railway contractors were

the

biggest

new

customers

for

Angolan labour. Work on the

'

Trans-African' railway had begun

at Luanda in 1886; by 1909

it

had reached Malanje.

In

1904 work

began

on the

Benguela railway which

was

originally meant

to

carry

out

copper from Katanga. This project

ran

into financial

522

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008