Roberts A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: from 1905 to 1940

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

SPANISH EQUATORIAL GUINEA

The choice of the vicar apostolic to head the new body reflected

the position of the missionaries as the only group which made an

attempt to win the confidence of Africans and protect them from

the worst abuses of the planters. On the eve of the First World

War, the Claretians had seven stations on Fernando Po, one on

Annobon, and five along the coast of Rio Muni. The Protestants

were less numerous,

in

spite

of a

head start

in

the nineteenth

century, as the Spanish authorities showed considerable hostility

to missionaries who were not only heretics but also insisted on

speaking and teaching English rather than Spanish. There was

a

single American Board Presbyterian mission

on

the mainland,

famous

for its

hospital, and five English Primitive Methodist

stations

on

Fernando Po. The Methodists made attempts

to

penetrate Bubi society, but most

of

their work was with

the

Fernandinos, and they were peculiar in their refusal to open any

schools. Government primary schools were set up

in

the three

main urban centres after 1914, but

it

was not until the very end

of the 1930s that the state began

to

create

a

network

of

rural

schools.

At the end of this period, Equatorial Guinea was briefly caught

up

in the

bloody events

of

the Spanish civil war. Incidents

between the

'

lay' authorities and the

'

clerical' opposition devel-

oped in

1936,

as some churches were closed and the heady rhetoric

of the Popular Front began to be applied to the African majority

in the colony. When General Franco rose against the republic, the

head of the colonial guard in Santa Isabel pronounced in Franco's

favour and declared himself governor-general. The republicans

gave way without

a

fight on Fernando Po, but the governor of

Rio Muni refused

to

follow suit and defeated the levies raised

against him by the timber bosses. The right-wing rebels sent

a

ship from the Canaries, which sank the ship loyal to the republic

in Rio Muni. Moroccan troops then seized Bata, the capital of the

enclave. Some republicans were captured and shot, but most of

them seem

to

have escaped into neighbouring Cameroun and

Gabon. By October 1936, the colony was securely

in

Franco's

hands and contributing money, raw materials and food to the long

and bitter campaign against the republic. Franco's victory ushered

in

a

new period

for

Equatorial Guinea, marked

by

greater

metropolitan interest and investment in its distant colony, but also

by more oppressive and more directly racist colonial rule.

543

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

ii

SOUTHERN AFRICA

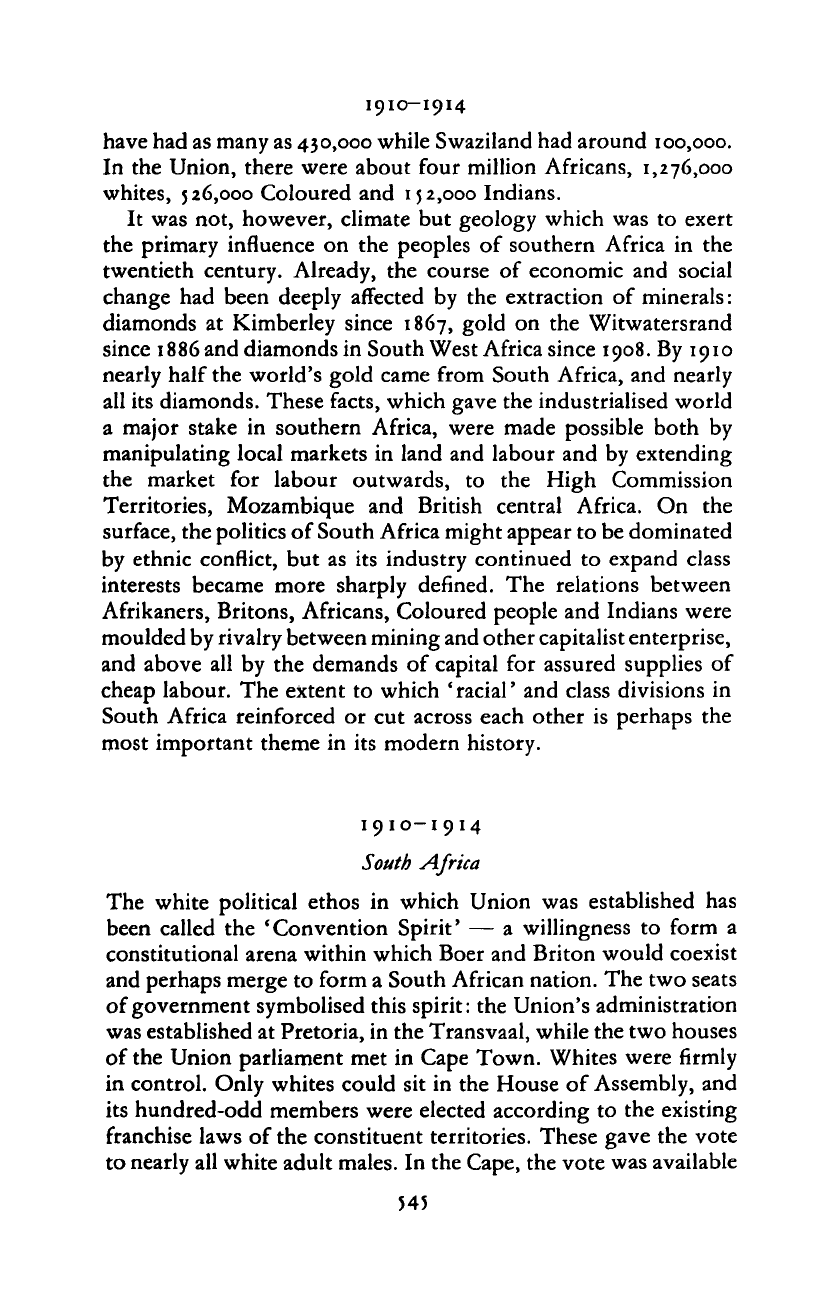

By 1910, three governments held sway

in

southern Africa over

a region

as

large

as

India and five times the size

of

France.

The

Union

of

South Africa, created

in

that year, was

a

self-governing

Dominion

in the

British Empire;

it

brought together, under

a

unitary constitution, the territories of the Cape, Natal, the Orange

River Colony and the Transvaal.

1

The British government, which

had thereby granted virtual independence

to

the white people

of

South Africa, retained responsibility

for

three adjacent protect-

orates: Bechuanaland, Swaziland and Basutoland. However, these

were closely tied

to the

Union; Basutoland

was a

mountain

enclave within it; and

all

three were administered by

a

British high

commissioner who until 1931 was also governor-general of South

Africa. South West Africa was

a

German colony,

but the

best

harbour along

its

coastline, Walvis Bay, belonged

to

the Union,

for the Cape Colony had annexed

it

before the Germans took over

the surrounding territory.

Geographically, southern Africa encompasses huge contrasts.

Its watershed,

the

Drakensberg range, falls abruptly

to the

east

coast and causes monsoon rains

to

fall over Natal and the eastern

Cape. For centuries this coastal belt had been colonised by African

mixed farmers; more recently, they

had

been joined

by

British

planters

and

Indian workers. Elsewhere,

the

only important

regions

for

arable farming were parts

of

the northern plateaux,

where Afrikaners had settled, and the south-western Cape, which

enjoys

a

Mediterranean climate: this

was the

heartland

of the

Coloured people. Otherwise, the western two-thirds

of

southern

Africa comprise arid grassland, scrub

and

desert, where annual

rainfall varies from 15 inches

to

little

or

none.

In

1911 there were

probably well under 200,000 people in South West Africa and less

than 150,000 in Bechuanaland.

In

sharp contrast, Basutoland may

1

The process of unification

is

considered, along with other developments before 1910,

in

The

Cambridge history

of

Africa,

vi

(1985).

544

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

1910-1914

have had as many as 430,000 while Swaziland had around 100,000.

In the Union, there were about four million Africans,

1,276,000

whites, 526,000 Coloured and 152,000 Indians.

It was not, however, climate but geology which was to exert

the primary influence on the peoples of southern Africa in the

twentieth century. Already, the course of economic and social

change had been deeply affected by the extraction of minerals:

diamonds at Kimberley since 1867, gold on the Witwatersrand

since

1886

and diamonds in South West Africa since 1908. By 1910

nearly half the world's gold came from South Africa, and nearly

all its diamonds. These facts, which gave the industrialised world

a major stake in southern Africa, were made possible both by

manipulating local markets in land and labour and by extending

the market for labour outwards, to the High Commission

Territories, Mozambique and British central Africa. On the

surface, the politics of South Africa might appear to be dominated

by ethnic conflict, but as its industry continued to expand class

interests became more sharply defined. The relations between

Afrikaners, Britons, Africans, Coloured people and Indians were

moulded by rivalry between mining and other capitalist enterprise,

and above all by the demands of capital for assured supplies of

cheap labour. The extent to which 'racial' and class divisions in

South Africa reinforced or cut across each other is perhaps the

most important theme in its modern history.

1 910-1914

South Africa

The white political ethos in which Union was established has

been called the 'Convention Spirit' — a willingness to form a

constitutional arena within which Boer and Briton would coexist

and perhaps merge to form a South African nation. The two seats

of government symbolised this spirit: the Union's administration

was established at Pretoria, in the Transvaal, while the two houses

of the Union parliament met in Cape Town. Whites were firmly

in control. Only whites could sit in the House of Assembly, and

its hundred-odd members were elected according to the existing

franchise laws of the constituent territories. These gave the vote

to nearly all white adult males. In the Cape, the vote was available

545

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SOUTHERN AFRICA

0

20"S

\

SOU

V

4

Swakopmund*'^

N

G O L A

,

6°

Tsumeb

1

J/H^ WEST

1

•,r*«sflsk

f fl 0

'I'

WalvisS*^ *41^ndhoek

Ba

V

T

Rehobfi.

\

1

A

\

Luderitz\v^

\

P ItCA

>g§

T

»'

V

•\

\

)

(

\

Orange

""' .

J

..

te,

CapeTowr

ys^llenbp^

Simonstown

^?>

1

2o|°f

\V

B

EC

H

\

U A N

A-^

N

LAN

D

Y

F

/

"*

-^

h

:

.

/p

l/

P

NGWATO

J

I?

V

/ /

i boron

A

^

^

liA/lUrlt)/

^

'"Rrt

Elizabeth

// Salisbury

|

3

/\

-

,'f

Xo

U

TJH ER

N

>M1^

\

> * | ffl

\^

'

2Q°s

•y«-^Bulawayo

'S

4

ti

RH0DESIA

{

<

•

«\ s

•

0

'

\\

™"

S

\m Wrenci

If

/

"East London

1

1

Land over 150Ometres

9

,

t L

590km

6~

360

miles

19 South Africa, South West Africa

and the

Protectorates,

1920

to

all

adult males,

of

whatever colour,

who

could meet

a

property qualification and pass

a

literacy test: thus only four

out

of five Cape voters were white.

The

Cape franchise could only

be altered

by

a

two-thirds majority

of

both houses

of

parliament

in joint session. This provision also protected the equal status

of

English

and

Dutch

as

official languages.

The

electoral system

favoured rural voters, who were mostly Afrikaners:

an MP in

a

rural constituency

was

allowed

to

represent

26 per

cent fewer

voters than were required

for an

urban member. There were

few

constraints

on

the

power

of

the House

of

Assembly.

The

four

constituent territories

now

became provinces, with councils

which were essentially large-scale organs

of

local government:

they could legislate

on

education, roads

and

hospitals,

but

they

546

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

1910—1914

had few

fiscal

powers and depended heavily on central government

revenues. The Senate could at most delay legislation, and in any

case was largely a creature of the lower house: MPs and provincial

councils elected eight senators for each province, while the

government nominated eight more. The governor-general norm-

ally acted on the advice of the Cabinet; it was thus that he

appointed the judges of the Union's Supreme Court, who could

only be removed at the request of both houses of parliament. As

in the other Dominions, Britain retained final authority over

external affairs. For the time being, the defence of South Africa

continued to be entrusted to imperial (i.e. British) troops and the

Royal Navy, which used Simonstown as a strategic base.

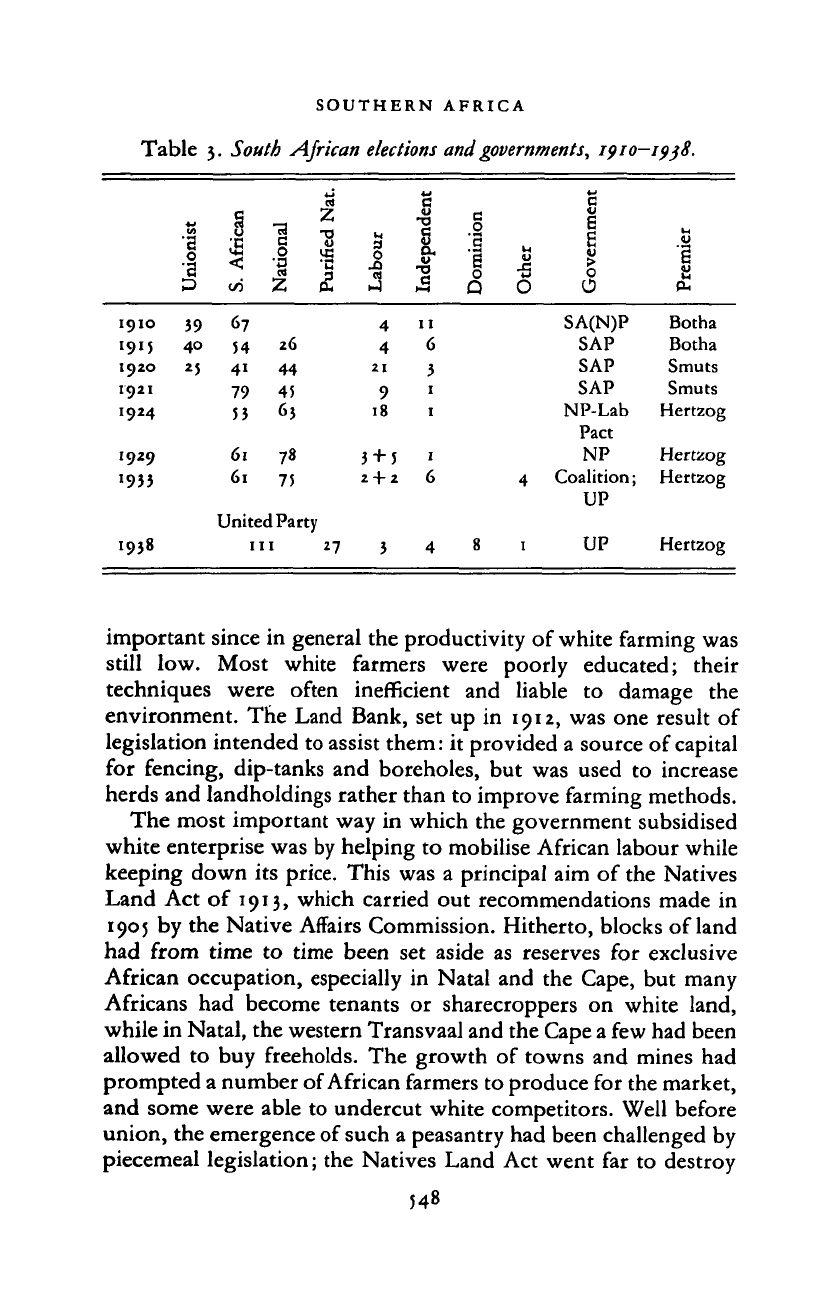

The general election in 1910 brought into power a government

headed by General Botha of the Transvaal. His base was a loose

coalition of Afrikaner parties, supported by

a

minority of English-

speaking South Africans, though Botha included three in his

Cabinet. Once the new government had been formed, Louis Botha

and Jan Smuts's Het Volk, the Cape's South African Party

(including the Afrikaner Bond) and General Hertzog's Orangia

Unie merged in 1911 to form the South African National Party.

The opposition was divided along class lines. English-speaking

Unionists represented commerce, finance, mining and Natal

agricultural interests. A small Labour Party, dominated by

Englishmen and led by Colonel Creswell, represented the restive

white working class, within which Afrikaners were a growing

minority.

From the first, the new government sought to influence the

direction of economic growth, though the main dynamic was

private enterprise, aided by British and European capital and

Empire trade preferences. In the first few years of Union, mining

generated 27 per cent of national income, agriculture 17 per cent

and manufacturing 7 per cent. In 1913 domestic exports were

worth

£64111;

two-thirds of this came from gold and the remainder

from diamonds, wool and agriculture. These results were achieved

through systematic institutional pressures. Railway rates, which

hitherto had been chaotically competitive, were gradually co-

ordinated. Farm exports were rated below mineral exports; they

were also assisted by a 'tapering rate' which reduced the tariff per

ton as distance increased, thus favouring the remoter areas as

branch lines were extended. Such discrimination was the more

547

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SOUTHERN AFRICA

Table

3.

South African

elections

and governments,

1910

1915

1920

1921

1924

1929

1933

1938

nist

0

a

39

40

rican

to

67

54

4i

79

53

61

61

1

0

1

26

44

45

63

78

75

United Party

1:

11

ed

Nat.

II

Pur

3

O

4

4

21

9

18

3

+

5

2

+

2

3

tendent

sr

Ind

11

6

3

1

1

1

6

4

nion

0

Q

8

U

O

4

1

rnment

0

0

SA(N)P

SAP

SAP

SAP

NP-Lab

Pact

NP

Coalition;

UP

UP

ier

e

Pre

Botha

Botha

Smuts

Smuts

Hertzog

Hertzog

Hertzog

Hertzog

important since

in

general

the

productivity

of

white farming was

still

low.

Most white farmers were poorly educated; their

techniques were often inefficient

and

liable

to

damage

the

environment.

The

Land Bank,

set up in

1912,

was one

result

of

legislation intended to assist them:

it

provided

a

source

of

capital

for fencing, dip-tanks

and

boreholes,

but was

used

to

increase

herds and landholdings rather than

to

improve farming methods.

The most important

way in

which

the

government subsidised

white enterprise was by helping

to

mobilise African labour while

keeping down

its

price. This

was a

principal

aim of

the Natives

Land

Act of

1913, which carried

out

recommendations made

in

1905

by the

Native Affairs Commission. Hitherto, blocks

of

land

had from time

to

time been

set

aside

as

reserves

for

exclusive

African occupation, especially

in

Natal

and the

Cape,

but

many

Africans

had

become tenants

or

sharecroppers

on

white land,

while in Natal, the western Transvaal and the Cape a few had been

allowed

to buy

freeholds.

The

growth

of

towns

and

mines

had

prompted a number of African farmers to produce

for

the market,

and some were able

to

undercut white competitors. Well before

union, the emergence

of

such

a

peasantry

had

been challenged

by

piecemeal legislation;

the

Natives Land

Act

went

far to

destroy

548

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

1910-1914

it. In 1913, Africans owned 7.3 per cent of the country, either

communally, as in the reserves, or as freehold. The Act now

prohibited Africans from buying land outside such 'scheduled

areas',

except at the discretion of the governor-general. More

immediately important, the Act prohibited sharecropping; it

required Africans remaining on white property to provide 90

days'

labour each year for their landlord; and it severely curtailed

the mobility of farm labour. White farmers began to terminate

rental agreements, recognising that their erstwhile tenants were

now obliged either to work for them or to seek work elsewhere.

For the time being, however, it was impossible to apply the Land

Act to the Cape; the Supreme Court ruled in 1917 that it interfered

with African voting rights there which were based in part on

landownership, and since the Act had not been passed by the

two-thirds majority needed to curtail these rights, it was invalid.

The need for cheap labour was acutely felt by the mining

industry. The gold mines had for some time been unable to rely

on market forces alone to meet their labour requirements. They

sold their whole output to the Bank of England at a fixed price;

thus the income from sales could not properly reflect the costs

of production, which were high, and likely to

rise.

The gold mines

mostly exploited low-grade ores at ever-deeper levels: by 1913

more than 40 per cent of dividends were derived from mines at

4,000 feet or more below ground. Furthermore, the nature of the

rock called for elaborate structures to prevent collapse. This

meant that mining on the Rand was unusually labour-intensive.

Yet the mine companies' wage bills were artificially inflated by

the industrial colour-bar, whereby skilled jobs were reserved for

whites earning far more than Africans: in 1911 this was embodied

in regulations made under the Mines and Works Act. Thus the

mines were bent on paying as little as possible for the great mass

of unskilled labour which they needed.

To some extent they achieved this by avoiding competition

among themselves. Already the high cost of gold production had

brought about

a

concentration of ownership in the industry. Most

of the Rand mines, and many coalmines, were owned by six large

firms, and these in turn partly depended for finance on profits from

the diamond industry, which was almost entirely owned by De

Beers.

This concentration greatly facilitated collusion among

mine-owners to prevent competition for labour and thus minimise

549

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SOUTHERN AFRICA

2SPt

BECHUANALAND

26 °S

I

I

Land over 1500 metres

9

,

390km

0 200miles

20 South Africa,

1937

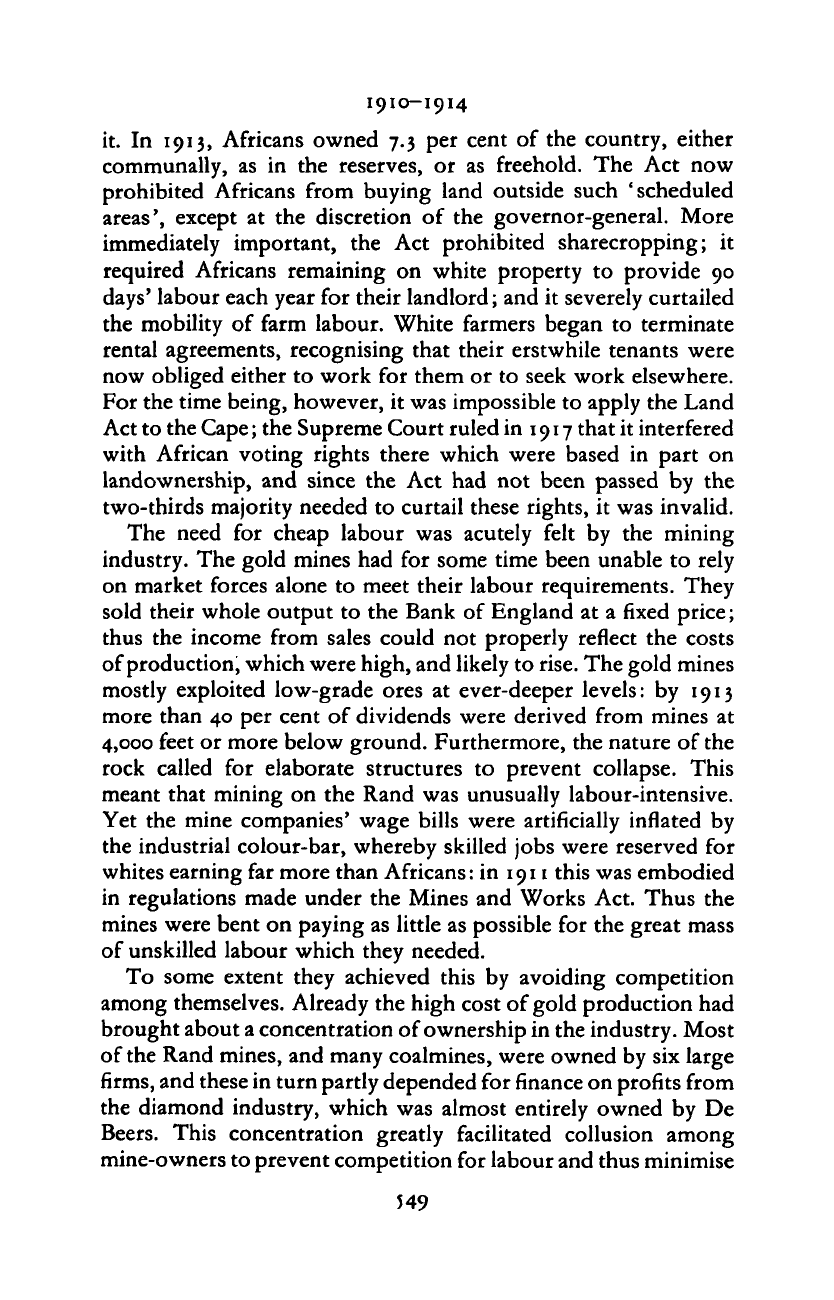

wages. Yet industrial collusion alone was not enough; the power

of the state was also needed. Thus

in

191a the Native Recruiting

Corporation

was

given

the

sole right

to

recruit labour

for

the

goldmines within

the

Union

and the

High Commission Territ-

ories.

The long-established Witwatersrand Native Labour Assoc-

iation, which recruited in Mozambique and British Central Africa,

was forbidden

in

1913

to

recruit north

of

latitude 22°S: black

miners from the tropics were especially susceptible

to

pneumonia

in

the

Transvaal winters,

and

their death-rate (about

70 per

thousand

per

annum

in

1911) provoked

the

Union government

to impose

a

ban which the Labour Party welcomed, since

it

made

55O

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

1910-1914

it harder for the mines to replace whites by cheap black labour.

By 1916, nonetheless, the Chamber of Mines employed 219,000

Africans, nearly all in the goldmines. About half came from within

the Union (mainly the eastern Cape and Transvaal), 12 per cent

from the High Commission Territories (mainly Basutoland) and

38 per cent from Mozambique. Of those from the Union and the

HCTs, about 60 per cent were recruited on contracts lasting from

three months to a year; recruits from elsewhere were bound by

contract for up to eighteen months. Within the Union, both

recruited and 'voluntary' workers were drawn on to the labour

market by the Natives Land Act. In 1911 the Native Labour

Regulation Act, consolidating earlier laws, had confirmed that

breach of contract by Africans was still a criminal offence, and had

outlawed African strikes, even if it also sought to control the

treatment of labour by employers and recruiters. The combined

effect of all these measures was to hold down African wages to

the barest minimum. In 1912 the ratio between the wages of white

and black mineworkers (including the latter's rations) was 9:1,

and over the next decade it steadily increased. African workers,

in the mines and elsewhere, were paid, fed and housed only as

single men, while their families were left to support themselves

as best they could in the reserves.

By 1915 no more than half the African population were living

in the reserves: they were tending to become now mere labour

reservoirs. The old patterns of shifting cultivation had once been

capable of yielding considerable grain surpluses, but under the

new constraints a syndrome of impoverishment began to take

hold. The pressure of human and animal population increased;

soil erosion spread rapidly; and labour migration became the very

basis of survival rather than just a means of paying poll-taxes and

supplementing income. Government policies were deliberately

framed to promote acute land shortages, the lack of cash-crops

and extensive migrant labour. Unlike white farmers, Africans had

no lobby in parliament to secure credit through a Land Bank.

Indebtedness rose sharply; a co-operative movement struggled

without official encouragement; there were no railway branch-

lines into the reserves; and the retention of the principle' one man,

one plot' meant a decline in family acreage.

The first Union census, in 1911, showed that one in eight

Africans, and half the European, Coloured and Indian commun-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SOUTHERN AFRICA

ities,

were living in towns. The urban Africans exceeded half a

million and already comprised

a

third of the total urban popul-

ation; there were over 100,000 in Johannesburg alone. For most

of them, conditions were very bad. Urban wage structures had

been determined when families were maintained by subsistence

agriculture. The reality was now likely

to be

very different.

Malnutrition was widespread in the reserves, on white farms and

in the expanding slums. In the municipal locations set aside for

Africans, sanitation was usually non-existent; the water supply

was often an irrigation furrow; and many Africans had to house

themselves in shanties built from packing-cases, flattened tins and

sacking.

The

crowded mining barracks

at

least provided

a

controlled diet and some recreational and hospital facilities, but

from 1903 to

1920

some

5,000

African miners died every year from

accidents and disease as tuberculosis spread rapidly. Among the

Coloured people of the Cape, conditions were, if anything, rather

worse, for they had no land for subsistence agriculture. Malnut-

rition was endemic and the incidence of tuberculosis

at

least as

high — that is four to six times the rate among Europeans.

In

addition, alcoholism was rampant, having its roots

in

the 'tot'

system of the vineyards where Coloured labourers received two

quarts of wine per day as part-payment. The only exceptions

to

this depressing picture were the small elite of teachers and clerks,

and the skilled workmen who came

to

enjoy some protection

within white-run trade unions.

If Africans as well

as

Coloureds and Indians had been indignant

after the Anglo-Boer War at Britain's failure to extend the Cape's

' native' policy to the northern colonies, they were appalled when

early in 1909 the National Convention produced the colour-bar

clauses

of

the draft South Africa Act.

A

South African Native

Convention promptly met

to

condemn the clauses and exhort

Britain to maintain and extend the Cape common roll. When their

protests, memorials and

a

delegation

to

London failed,

the

Convention ceased to exist. However, it was soon replaced by the

South African Native National Congress, which was formed

at

Bloemfontein in 1912. This was essentially

a

middle-class body,

with close ties

to

chiefs.

Its

members came from all over the

country and were dedicated

to

promoting national rather than

ethnic unity; most were lawyers, teachers, clergymen and journa-

lists,

though

a

few were traders and farmers. Some had been

to

55*

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008