Roberts A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: from 1905 to 1940

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE GROWTH OF MODERN POLITICS

On one major issue the northern associations could claim to

have scored a distinct success. This was the question of 'closer

union'. In 1928 the Hilton Young Commission explored the

prospects for closer union in East Africa, Northern Rhodesia and

Nyasaland. This prompted the Southern Rhodesian prime

minister, Moffat, and several settlers in Northern Rhodesia to

express their preference for an amalgamated Rhodesia. The

commission, however, concluded that such union would not be

in the interests of Africans and in 1930 the Labour colonial

secretary, Lord Passfield, reaffirmed the principle that African

interests should prevail in any conflict with those of immigrant

races.

27

This had little effect on colonial governments, but it

reinforced the belief of settlers in Northern Rhodesia that their

salvation must lie in union with the south, as did the shock of

the African strikes on the Copperbelt in 1935. Many whites in the

south also supported amalgamation, which now offered hopes of

a share in the new-found wealth of the Copperbelt. In January

1936 a conference at Victoria Falls of settler representatives from

both north and south called for early amalgamation of the

Rhodesias and 'complete self-government', i.e., the removal of

Britain's reserve powers in the south. Meanwhile, in April 1935,

all three governors in Central Africa had agreed with Huggins,

the Southern Rhodesian prime minister, on the need for closer

inter-territorial co-operation in several fields. These converging

pressures induced Britain, in

1937,

to appoint

a

Royal Commission

to consider closer co-operation or association between the Rhod-

esias and also Nyasaland, whose labour was crucial to the whole

region.

The commission was chaired by Lord Bledisloe, a former

governor-general of New Zealand, and included MPs from the

three main British political parties, a businessman, and the former

director of East Africa's unified postal system. In 1938 the

commission took evidence from whites in all three territories, and

also from African groups north of the Zambezi, though not in

Southern Rhodesia. The African evidence came from native

authorities, welfare associations, teachers, civil servants and

mineworkers. All voiced emphatic and often well-argued opposi-

tion to amalgamation. Most had seen the south for themselves and

knew that even if some Africans there were materially better off

" See above, p. 64, and below, p. 687.

643

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH CENTRAL AFRICA

than those in the north, they were consistently denied opportun-

ities to make the most of their abilities; besides, they had lost most

of their land and were harassed by pass-laws. The commission was

impressed

by its

African witnesses and duly reported that 'the

striking unanimity,

in the

northern territories,

of the

native

opposition

to

amalgamation...[is

a

factor] which cannot

in

our

judgment be ignored'. The commissioners were divided as to the

inherent desirability of amalgamation but agreed that it should be

postponed

for

the time being, since the subjection

of

so many

people to a unified government against their will' would prejudice

the prospect

of

co-operation in ordered development'.

28

Within

a year, the Second World War cut short further discussion of the

question. The commission's equivocal and irresolute report did

not by any means

close

the door en white hopes of amalgamation,

29

but

it

did give Africans

in

the north some reassurance that their

opinions mattered, and

in

Nyasaland,

at

least,

its

enquiries had

served

to

strengthen among African leaders

a

growing sense of

territorial,

if

not yet national, identity.

Faced from the late

1920s

with increasing economic deprivation,

few

of

Central Africa's rural inhabitants found much assistance

in the new associations. Instead, they took refuge in

a

variety of

religious movements which appeared

to

offer more convincing

answers

to

the problems that now confronted them. Misfortune

was still commonly believed to derive principally from the action

of witches. But whereas

in

the nineteenth century the welfare of

the land was a primary religious concern, by the 1920s the welfare

of individuals appears

to

have grown more important,

a

development associated with the enhanced importance bestowed

on an active, interventionist High God in most people's systems

of

belief.

Millennialist ideas took root, and though some

of

the

prophetic movements that resulted were

of a

localised nature,

others spread over

the

greater part

of the

region. Specially

important were the ideas

of

the New York-based Watch Tower

Bible and Tract Society (Jehovah's Witnesses), whose literature

foretold

the

imminent

end of

the world

in its

existing form.

Outside the mines of Katanga and Southern Rhodesia where they

28

Quoted

in

Richard Gray,

Tie

two nations. Aspects

of

race

relations

in the

Khodesias and

Njasaland (London, i960), 177, 193.

29

W. K.

Hancock, Survey

of

British Commonwealth affairs, 11. Problems

of

economic

policy

8—19)9,

part

2

(London, 1942), 124—7.

644

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE GROWTH OF MODERN POLITICS

appealed mainly to a literate minority, African Watch Tower

preachers were influential up to 1920 only in scattered districts

of Nyasaland and in the north-east of Northern Rhodesia. But in

1924 returning migrants from the Wankie colliery evoked a

massive if transitory response in the Luapula valley. This was

followed over the next few years by a succession of waves of

popular enthusiasm in northern Mashonaland, between 1925 and

1929,

and among the Lala of Northern Rhodesia where Tomo

Nyirenda's witch-killing exploits in 1925-6 gained the movement

unwelcome publicity. Watch Tower doctrines appealed in the

early 1930s to the exploited Wiko people of Barotseland, resentful

of Lozi domination. Elsewhere, the supervisors appointed in the

mid-1930s to Zomba and Lusaka from white South African Watch

Tower congregations probably weakened the movement through

their repudiation of the practices of many rural congregations

which had taken on a character of their own.

While Watch Tower preachers prepared for the Second Coming

by seeking in a number of different ways to restructure rural

societies, movements of witchcraft eradication concentrated

instead on cleansing those societies once and for all of

evil.

Long

before the twentieth century, generalised attempts to eradicate

witchcraft appear to have occurred occasionally in a number of

societies as alternatives to more conventional procedures of

detecting individual witches. But with the establishment of

colonial rule, confidence in these conventional procedures was

weakened by the outlawing of the poison ordeal which chiefs had

previously used to test individual cases. And further tension was

created during the depression with the return home of thousands

of unemployed migrants, many of whom found difficulty in

reconciling the achievement-orientated assumptions of the new

economic order with the community-orientated morality of the

village. The result was the emergence of a number of witchcraft

eradication movements, directed, so it has been suggested 'not

so much against individual sorcerers...but against sorcery as a

frame of reference and an institution'.

30

By far the most popular

and the most far-flung was the

mchape

movement of

1933—4.

The

movement originated in the Mlanje district of Nyasaland, whence

it

was

carried by vendors selling medicine into Northern Rhodesia,

30

W. M. J. van Binsbergen, 'The dynamics of religious change in western Zambia',

Ufabamu, 1976, 6, 5, 81-2.

645

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH CENTRAL AFRICA

Tanganyika, Mozambique and Southern Rhodesia. Those who

gave

up all

charms and drank

the

medicine were promised

freedom from

all

witchcraft, with the threat that those who

attempted witchcraft thereafter would suffer instant death.

In

village after village

a

sense of communal purification was achieved,

though inevitably

it

failed to last for long.

The desire for healing that existed within the

mchape

movement

was even more prominent in the Spirit-type churches of Southern

Rhodesia, the area of Central Africa least affected by

mchape.

Spirit

healing can be traced

in

southern Africa from its roots

in

the

evangelical tradition

of

the Dutch Reformed Church, through

contacts with American evangelists,

to

the creation

in

South

Africa

of a

large number

of

Zionist churches.

In

Southern

Rhodesia the key agents were workers returning from the south

where they had been attracted to the Zionist message. In the 1920s

they introduced Zionism into western Mashonaland and by the

1950s were attracting

a

substantial following, predominantly

among Shona cultivators previously uninvolved

in

mission

Christianity. The Vapostori movement of Johanne Maranke

in

eastern Mashonaland obtained particularly widespread support.

Led by

a

charismatic prophet famed for his healing powers, the

Vapostori combined

a

radical assault

on

many traditional

approaches

to

misfortune with

an

appeal

'to

the fundamental

notions of healing, prophecy and exorcism which had formed the

basis

of

Shona traditional religion'.

31

By 1940

adherents

received communion from the founder at over

a

hundred sites.

It

is

an indication of the substantial inroads that Christianity

had made

in

Central Africa by the 1930s that, though disillus-

ionment concerning the transforming power of the Gospel was

at its height during this period, many Africans followed orthodox

paths

in

their search for religious initiative. The leaders

of

the

independent churches founded

in

northern Nyasaland between

1928 and 1934 possessed theological views not dissimilar from

those held

in the

Presbyterian church from which they

had

broken, along with

a

passionate belief in the virtues of modern

economic and educational training. Their answer to the collapse

of the migrant labour economy was thus not

a

withdrawal into

passive millennialism but rather a desperate if unavailing struggle

to create independent schools and colleges of a quality sufficient

31

T. O.

Ranger, The African

voice

in

Southern

Rhodesia ifyf-ipjo (London, 1970), 221.

646

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE GROWTH OF MODERN POLITICS

to supply Africans with the techniques that mission education was

not providing. In 1934 the independent church leader Y. Z.

Mwase founded the Nyasaland Black Man's Educational Society,

' to improve and develop the impoverished condition of the black

man...by starting a Purely Native Controlled high school or

college'. Such organisations met with little practical success, but

they were significant as attempts by Africans to take the process

of improvement into their own hands.

32

Under such ministers as

Hanoc Phiri in Nyasaland and John Membe in Northern Rhodesia,

networks of schools were established under the control of the

African Methodist Episcopal Church and rivalled those of the

older missions. Even where Christians did not leave the mission

churches, they were often active in such urban centres as the

Copperbelt and the Harare township of Salisbury in creating

interdenominational churches virtually independent of missionary

control.

For all the variety of African initiatives in the inter-war years,

colonial authority remained secure in 1940. Bodies such as the

Bantu Congress of Southern Rhodesia or the grandly-named

Northern Rhodesia African National Congress, founded among

the Plateau Tonga in 1937, were still primarily elite accommoda-

tionist bodies incapable of exerting effective pressure on the

government. Urban unrest was still too disorganised, small-scale

and sporadic to cause more than occasional inconvenience. The

answers sought in rural areas tended to draw people away from

confrontations with the authorities, though the colourful imagery

of independent Watch Tower preaching, with its emphasis on the

arrival of black Americans in aeroplanes and the consequent

removal of the

whites,

struck discordant notes that the government

would have preferred not to hear.

At a deeper level, however, there are indications to suggest that

the network of local alliances so carefully woven in the earlier

years of the century was becoming badly frayed in the 1930s. For

reasons that have still not been adequately explored, African

policemen and soldiers appear to have been largely untouched by

the widespread crisis of confidence in the colonial order that

spread through the ranks of African intermediaries. But many

chiefs, upon whose shoulders responsibility in the local areas had

been placed, were not immune to the infection. The success of

32

For further details, see McCracken, Politics and Christianity, 28J.

647

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BRITISH CENTRAL AFRICA

Watch Tower, 'first of the twentieth-century mass movements to

demonstrate the collapse of chiefly power',

33

gave warning of the

paradox that the more authority colonial officials transferred

to

chiefs,

the

less respect they could expect from their African

subjects.

Ila

chiefs opposed

to

the activities

of

Watch Tower

prophets

in

1934 were either compelled

to

accede

to

public

demand or else were forced from office.

Mchape

vendors organised

village ceremonies whether chiefs co-operated or not. As govern-

ment intervention became more active

in

the aftermath

of

the

depression, so the weakness of their agents was exposed. Several

Plateau Tonga farmers responded positively from 1936

to

the

introduction of the so-called Kanchomba system, which employed

farmers to demonstrate improved agricultural techniques to their

neighbours. But by introducing a measure of compulsion into its

proposals for stemming soil erosion, the agricultural department

placed

a

burden on

its

African intermediaries that would eventually

provoke

resistance.

So

resentful were growers

in

central Nyasaland

at the low prices paid

for

their tobacco

by

the government-

controlled marketing board that

in

1937 they burnt their crops

and upset their baskets on the roads.

33

Ranger, African

voice,

Z12.

648

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

13

EAST AFRICA

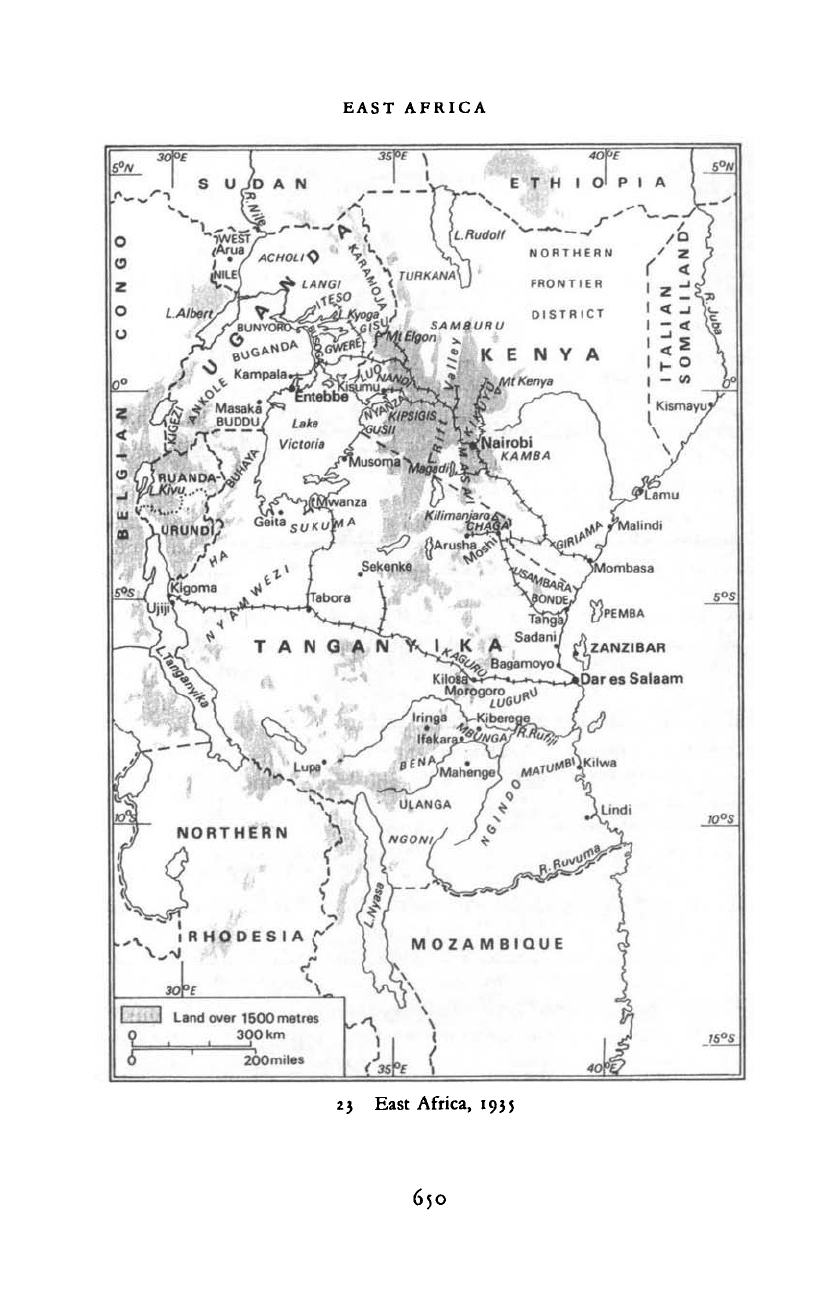

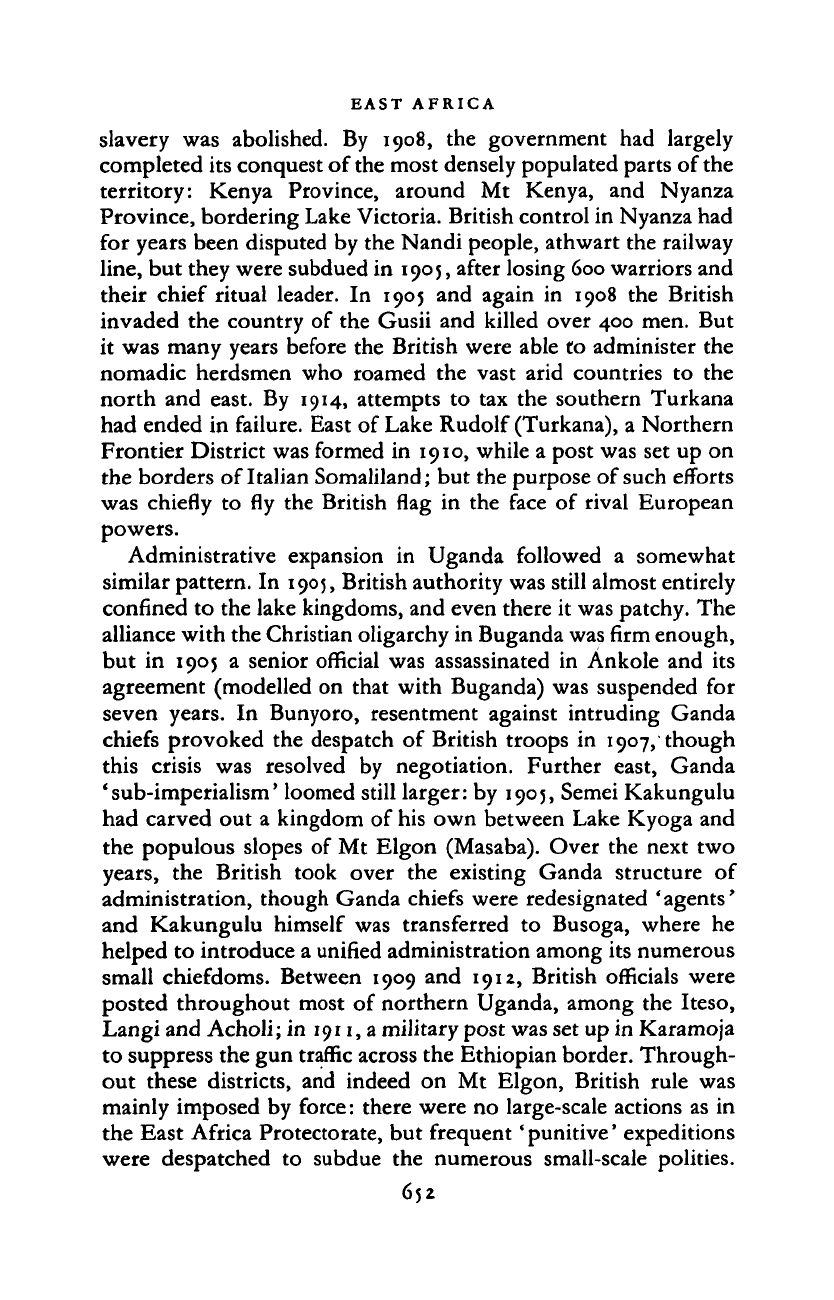

By 1905, the British and the Germans had occupied several

strategic points in East Africa. They were the latest of many

intruders from overseas. The coast and the offshore islands had

long shared in the commerce of

the

Indian Ocean. The expansion

of trade in the nineteenth century quickened the flow of Arab

immigrants and also prompted Indian traders to settle among the

black, and mostly Muslim, Swahili-speakers of the East African

littoral. The British government intervened in Zanzibar and

up-country mainly to secure the western flank of its Indian

empire: well into the twentieth century it continued to regard East

Africa as an appendage to India. But both British and Germans

also came to colonise the hinterland. The British had recently

completed the Uganda Railway, which ran from Mombasa

through scrub and desert to the temperate uplands south of Mount

Kenya, across the great Rift Valley and down to the shores of Lake

Victoria. The western part of this line skirted the populous

countries of the Kikuyu and Luo, and lake steamers completed

the link between the coast and the kingdom of Buganda. Here

the scope of British initiative was constrained by an agreement

reached in 1900 with a ruling elite already converted and educated

by Christian missionaries. But either side of the Rift there were

fertile and lightly occupied highlands which attracted white

farmers, especially from South Africa, while British planters

moved into western Uganda (the name used by the British for both

Buganda and much of the surrounding territory). Meanwhile,

German planters and farmers clustered round the hills of Uluguru

and Usambara, and the lower slopes of Kilimanjaro. As yet, there

were few white immigrants, but their governments assumed that

they had a crucial role to play in promoting economic and cultural

change, while the settlers themselves expected a share in

government. At the same time, colonial rule in East Africa

attracted a new wave of Indian traders, and also Indian clerks and

649

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EAST AFRICA

K

E N Y A

Land over

1500

metres

0 300 km

200miles

23 East Africa,

1935

650

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

COLONIAL CONSTRUCTION

artisans. At home, of course, Indians were a 'subject race', and

Europeans tended to treat them as such in East Africa. But they

were also feared as possible rivals: Indians too contributed

modern skills, and many identified themselves with European

efforts to 'civilise' Africa. In 1905 it remained to be seen whether

immigrants would be given effective political roles in East Africa:

if they were, the question of racial balance would clearly be hotly

debated. Beyond this, however, white settlement raised a still

more fundamental issue: the balance to be struck in assigning

land, labour and capital as between Europeans and the indigenous

African population. How this should be resolved was still very

much an open question.

COLONIAL CONSTRUCTION, I905-I914

The consolidation of colonial rule

Between 1905 and the outbreak of the First World War, the

colonial governments in East Africa extended their grasp over

most of the region. At the same time they were placed on a more

regular footing than hitherto. In the heat of the Scramble, Britain

and Germany had had to run up their respective flags hundreds

of miles from the coast, and each Foreign Office had hastily

improvised local administrations from whatever personnel lay to

hand: mainly army officers, civil servants borrowed from the

metropolis and adventurers rescued from ruined chartered com-

panies. It took several years to establish routines of command and

recruitment.

The British ruled three territories: the protectorates of Zanzibar

and Uganda, and the East Africa Protectorate (the future Kenya).

All three were subject to legal codes compiled for India by British

reformers in the nineteenth century. Such law controlled those

spheres of greatest interest to immigrants: taxation, communica-

tions,

property, criminal law and procedure.

1

In 1905 Uganda

and the East Africa Protectorate were transferred from the care

of the Foreign Office to that of the Colonial Office. In 1907 the

northern frontier of the East Africa Protectorate was defined by

agreement with Ethiopia; the capital was moved from Mombasa

to Nairobi, near the 'white highlands', and the legal status of

1

The substance of these Indian codes was retained until after 1930, when Britain began

to replace them.

651

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EAST AFRICA

slavery was abolished. By 1908, the government had largely

completed its conquest of

the

most densely populated parts of the

territory: Kenya Province, around Mt Kenya, and Nyanza

Province, bordering Lake Victoria. British control in Nyanza had

for years been disputed by the Nandi people, athwart the railway

line,

but they were subdued in 1905, after losing 600 warriors and

their chief ritual leader. In 1905 and again in 1908 the British

invaded the country of the Gusii and killed over 400 men. But

it was many years before the British were able to administer the

nomadic herdsmen who roamed the vast arid countries to the

north and east. By 1914, attempts to tax the southern Turkana

had ended in failure. East of Lake Rudolf (Turkana), a Northern

Frontier District was formed in 1910, while a post was set up on

the borders of Italian Somaliland; but the purpose of such efforts

was chiefly to fly the British flag in the face of rival European

powers.

Administrative expansion in Uganda followed a somewhat

similar pattern. In 1905, British authority was still almost entirely

confined to the lake kingdoms, and even there it was patchy. The

alliance with the Christian oligarchy in Buganda was firm enough,

but in 1905 a senior official was assassinated in Ankole and its

agreement (modelled on that with Buganda) was suspended for

seven years. In Bunyoro, resentment against intruding Ganda

chiefs provoked the despatch of British troops in 1907, though

this crisis was resolved by negotiation. Further east, Ganda

'sub-imperialism' loomed still larger: by 1905, Semei Kakungulu

had carved out a kingdom of his own between Lake Kyoga and

the populous slopes of Mt Elgon (Masaba). Over the next two

years,

the British took over the existing Ganda structure of

administration, though Ganda chiefs were redesignated ' agents'

and Kakungulu himself was transferred to Busoga, where he

helped to introduce a unified administration among its numerous

small chiefdoms. Between 1909 and 1912, British officials were

posted throughout most of northern Uganda, among the Iteso,

Langi and Acholi; in

1911,

a military post was set up in Karamoja

to suppress the gun traffic across the Ethiopian border. Through-

out these districts, and indeed on Mt Elgon, British rule was

mainly imposed by force: there were no large-scale actions as in

the East Africa Protectorate, but frequent' punitive' expeditions

were despatched to subdue the numerous small-scale polities.

652

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008