Roberts A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: from 1905 to 1940

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

TERRITORIAL CONTRASTS

should be a 'black man's country' on broadly West African lines

and, while much basic law was taken from Indian codes, Nigerian

models influenced plans for land law and African administration.

The policy of indirect rule, elaborated by Lugard into a doctrine,

was now

to be

adopted

in

Tanganyika. The first step

in

this

direction was taken

on

strictly financial grounds.

In

1920-2

Britain had to give the territory grants-in-aid worth £408,000;

it

therefore insisted that new means be found

to

increase revenue

and reduce expenditure. Byatt thought this could best be done by

increasing government's share

of

the proceeds from sales

of

African cash-crops. Hitherto, much of this income had been paid

to chiefs as tribute; henceforward, chiefs received

a

salary from

government while tribute payments were commuted to

a

monetary

tax additional

to

hut-

or

poll-taxes.

In

1925

a

new governor

arrived: Sir Donald Cameron, who had served in Nigeria for 17

years.

Cameron at once set about the introduction of indirect rule,

whereby chiefs became paid agents

of

local 'native administ-

rations' rather than

of the

central government.

A

native

administration comprised three bodies:

a

native authority,

whether chief or council;

a

native court; and

a

native treasury,

which collected

tax,

forwarded

a

percentage

to the

central

government and used

the

rest

to

pay

the

staff

of

the native

administration. It was hoped that native administrations, in close

touch with the people, would prove more efficient in prising taxes

out

of

African pockets than officials

of

central government;

it

seemed certain that they would be cheaper.

For Cameron, indirect rule was

not

just

a

means

to

more

efficient administration;

it

was also a way of training Africans to

take part eventually in territorial politics. But this was a long-term

aim. Like most

of

his colleagues, Cameron firmly believed that

Africans should not become 'bad imitations' of Europeans, but

develop along 'their own lines'.

It

was widely assumed that this

meant fostering the 'tribe' as the largest unit of African society,

and several

of

Cameron's subordinates tried

to

group native

administrations into tribal paramountcies, in the belief that they

were thereby repairing damage done by German rule to African

institutions. In practice, indirect rule often meant the introduction

of chiefs and paramounts without any traditional standing, but

such innovation was seen as a stage in a distinctively African path

of evolution. This approach influenced Cameron's views

on

675

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EAST AFRICA

African education, which echoed those of many missionaries and

also the Phelps-Stokes Commission which visited East Africa in

1924:

schools should make Africans 'useful members in their own

community life'.

7

It was in this spirit that the government began

to assist selected mission schools. In 1925 it refused to help

Africans learn alongside Indians, since this might give Africans

'political ideas'. In the same year, it founded a school at Tabora,

but for ten years entry was restricted to the sons of chiefs and

headmen.

Indirect rule provided new scope for African abilities, but it

was clearly far from being a programme for indiscriminate

African advancement; in important respects, it was a policy of

segregation. This was underlined in 1929, when the native courts

became part of a judicial pyramid from which professional

advocates were excluded and in which appeal lay through district

and provincial commissioners up to the governor, and not to the

High Court.

8

There was nothing incongruous in the fact that

Cameron simultaneously sought to promote white settlement. In

1925 Britain and Germany resumed normal relations, which

meant that Germans were once more entitled to settle in Tanga-

nyika. Many small farmers from Germany regained property on

Kilimanjaro, while others took up leases around Iringa, in the

southern highlands, where they vainly sought to make fortunes

from coffee. It therefore seemed highly desirable, both to Cameron

and the Colonial Office, that British settlers with a modicum of

capital and experience should be encouraged as a counterweight

to the Germans. In 1930-2 a survey team specified certain areas

as suitable for white settlement. Some preference was given in the

later 1920s to European coffee cultivation: Africans were denied

assistance in growing the more profitable

arabica

variety except

on Kilimanjaro, where it was already firmly established. Imperial

loans were obtained for railway extensions, not only from Tabora

to Mwanza but also from Moshi to Arusha, which was seen as

a centre for white farming. The economy became increasingly

dependent on European enterprise: while the total value of

exports was nearly quadrupled between 1921 and 1929 (when it

was £3.7m), the contribution of sisal rose from 22 per cent in

1921-3 to 40 per cent in 1929. This was achieved by accelerating

7

Thomas Jesse Jones,

Education

in East Africa (New York, n.d.), xvi.

8

Kenya followed suit, in 1950; Uganda, in the end, did not.

674

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

TERRITORIAL CONTRASTS

the flow of migrant labour from the remotest population clusters

in the south and west; the Ha were first systematically taxed

in

1923,

and in 1926

a

labour department was set up

to

supervise

labour migrants

in

transit. Meanwhile Europeans once more

obtained political representation and so too, for the first time, did

Indians.

In

1926

a

legislative council was formed, comprising

thirteen officials and seven nominated unofficial; five of the latter

were British whites and two were Indians, who

in

this context

were also British; non-British European residents were specifically

excluded. In 1929 two more unofficial whites and one Indian were

added. There was no revival of elections

in

urban government,

but Europeans

and

Indians were nominated

by

officials

to

township authorities.

It was Indians who pioneered political action on

a

territorial

scale in Tanganyika. Their meagre representation in the legislative

council was no measure of their importance. During the war they

had suffered greatly from

the

collapse

of

external trade,

but

afterwards the Tanganyika government drew heavily on India for

English-speaking clerks and artisans. As exports revived, Indian

traders increased, and

a

few bought sisal and coffee plantations.

By 1931, when the European population was 8,200, there were

25,000 Indians — four times their number in 1912. Meanwhile,

in 1918, an Indian Association had been formed, and

in

1923

it

helped to organise a closure of Indian and Arab shops throughout

the territory: this obliged the government to abandon an attempt

at closer supervision of traders' accounts.

The reassertion of the Indian presence had far-reaching effects

among Africans:

it

stimulated their awareness of belonging to

a

single colonial territory and prompted them to organise accord-

ingly. Ironically, the conditions for this were created by colonial

policy. Colonial officials might envisage African progress in terms

of tribes, and see the legislative council as the exclusive concern

of immigrants, but the British themselves had already sponsored

the advance

of

' detribalised' Africans. When the Tanganyika

government began looking for English-speaking staff at the end

of the war,

it

found them not only in India but among Africans

educated by British missions. Since the late nineteenth century,

the Universities' Mission

to

Central Africa (UMCA) had been

sending Africans from the mainland

to

Kiungani, on Zanzibar,

for training as priests or teachers. The German government had

675

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EAST AFRICA

distrusted such African Christians and gave them few jobs;

instead, they had favoured literate Muslims. When the British

took over, they soon gave key posts as government clerks and

interpreters to graduates of Kiungani and the Church Missionary

Society school at Mombasa, and also to educated Africans from

Nyasaland, Northern Rhodesia and Uganda. Such men resented

the predominance of Indians in the middle grades of the civil

service and the preferential treatment of Indian clerks. To

challenge this, in 1922 both Christians and Muslims in Tanga

founded the Tanganyika Territory African Civil Service Associ-

ation; in 1925—7 the branch in Dar es Salaam led a systematic if

unsuccessful campaign to improve terms of service and achieve

parity with

Indians.

In

its

early

years,

TTACSA mainly represented

a coastal elite, but its stronghold was the capital and framed a

perspective of the territory as a whole.

Meanwhile, educated Africans up-country were also coming

together: their field of action was the tribe, but their tribes were

economic communities rather than the administrative construc-

tions of colonial officials. In 1924 the Bukoba Bahaya Union was

formed by clerks in opposition to coffee-rich chiefs, and a similar

rivalry among the Chaga inspired the Kilimanjaro Native Planters'

Association, founded in 1925. This protected its members against

Asian coffee-traders by dealing through a single agent; it also

resisted threats of European encroachment and in 1929 even

sought representation in the legislative council. Such fears and

rivalries exposed the contradictions inherent in the compart-

mentalised structure of Tanganyika society; they were to become

more urgent as the structure was stiffened by a new economic

depression.

Kenya

In the East Africa Protectorate, in sharp contrast to Tanganyika,

white settlers were much more powerful at the end of the war than

at the beginning. Several had played key roles in government, and

most were well placed to take advantage of the post-war

commodity boom. By 1919 coffee contributed 25 per cent of

exports, and from 1920 onwards it was the country's leading

export, usually followed by sisal. High prices for both crops

encouraged further expansion, to which the main obstacle seemed

676

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

TERRITORIAL CONTRASTS

to be a shortage of African labour. This was due to the ravages

of

war.

Men who had survived and recovered were busy putting

their own farms back into commission; they were in no mood to

continue working for white men. So further measures were taken

to conscript them. In 1918 the Resident Natives Ordinance

compelled African squatters to work for their landlords for at least

six months of the year. In 1919 General Northey, a veteran of the

East Africa campaign, became governor, and he soon issued

circulars instructing district officials

to'

persuade' labour to come

forward. Meanwhile, the settlers' position had been strengthened

by the colonial secretary, Lord Milner, as part of a broader

strategy for entrenching British hegemony in eastern Africa. In

the legislative council, eleven (out of thirty) seats were to be filled

by election among the 9,000 Europeans. The 25,000 Indians were

allowed to elect two members but refused to do so; the Arabs

were given one nominated member. Britain also supported the

settlers' plan to double their numbers by offering farms on easy

terms to ex-servicemen. In 1920 the territory was renamed Kenya

Colony;

9

this had no constitutional significance but allowed the

government to raise

a

loan of

£5 m

in London, in order to improve

Mombasa harbour and extend the railway into Uganda through

European areas in the western highlands. In the same year,

African taxes were increased by one-third, and the Native

Registration Ordinance tightened the grip of both employer and

tax-collector by obliging every adult male African to carry a

registration certificate

(kipande).

At the end of 1920 the post-war boom collapsed; besides, most

people, of whatever colour, suffered losses as a result of the

conversion of East African currency from the Indian rupee to

sterling. For many Africans, wages were now the most likely

source of cash: economic circumstances pulled them on to the

labour market even as recent legislation pushed them. It has

indeed been reckoned that by 1922 an African had to work four

times as long as in 1910 to earn his tax money.

10

Thus when in

1921 the Colonial Office insisted that Northey withdraw his

9

The coastal strip remained, as before, a protectorate, under the entirely nominal

suzerainty of the sultan of Zanzibar. In 1925 Kismayu and territory west of the Juba

river was transferred to Italian Somaliland, to fulfil an agreement made with Italy in

1915.

10

R. L. Tignor, The

colonial transformation

of

Kenya.

Tie Kamba, Kikuyu and Maasai from

if

00

to if)f (Princeton, 1976), I8J.

677

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EAST AFRICA

circulars, it made little real difference, for labour was now cheap

and plentiful. In the same year a judge ruled that, since Kenya

was a colony, Africans could not own land as Europeans could;

they were mere tenants-at-will of the Crown. Meanwhile, settlers

showed that civil disobedience could succeed: they mostly refused

to pay an income-tax imposed in 1920 and it was withdrawn in

1922.

Against the steady advance of settler power, Africans now

began to organise resistance. In June 1921 a Kikuyu telephone

operator in the Treasury, Harry Thuku, founded the Young

Kikuyu Association. This campaigned both in Nairobi and in

Kikuyu reserves against the

kipande,

tax increases, forced labour

and land alienation. In March 1922 Thuku was arrested and

deported to the coast; this caused a riot in Nairobi in which over

twenty Africans were killed. By this time, Thuku's grievances

were also being voiced by Luo chiefs and by a Young Kavirondo

Association. This last included many Anglicans who until 1921

had belonged to the Uganda diocese, in which they had enjoyed

a high degree of self-reliance and autonomy. The Luo meetings

were taken seriously by the government, and in August the recent

tax increases were abolished. In 1923 the government sanctioned

the transformation of

the

Young Kavirondo Association into the

Kavirondo Taxpayers' Welfare Association, which under the

leadership of the Anglican Archdeacon Owen addressed itself for

some years to local self-help as well as to carefully worded

protests.

Meanwhile tensions between Europeans and Indians became

acute. In 1919 Northey had bluntly told the Indian Association

in Nairobi that European interests must be paramount, and early

in 1922 the new colonial secretary, Churchill, encouraged

Europeans to look forward to eventual self-government. But the

government of India, hard-pressed by nationalists, compelled the

British government to think again. In mid-1922 Northey was

replaced by the more flexible governor of Uganda, Robert

Coryndon. Whitehall now proposed to mollify Kenya's Indians

by creating a common roll for elections to the legislative council.

This frightened a group of white settlers into plotting rebellion:

plans were made to kidnap the governor. Early in 1923 the British

government arranged talks in London, at which settlers and

Indians sought to buttress their rival claims by championing the

rights of the African majority. Their bluff was called: after

678

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

TERRITORIAL CONTRASTS

suggestions from J. H. Oldham, secretary of the International

Missionary Council, the colonial secretary, now the Duke of

Devonshire, issued a White Paper which declared: 'Primarily

Kenya is an African territory...the interests of the African natives

must be paramount.'

11

In face of widespread settler opposition,

Indians were assured the right of unrestricted immigration and

were offered five (instead of two) communally elected seats in the

legislative council; but they scornfully ignored this concession

until

1933.

12

The Arabs gained one elected seat, while an official

seat was filled by the senior Arab liwali on the coast. African

interests were to be represented by one nominated European, a

missionary. Nobody had won, but tempers cooled as commodity

prices began to rise again. The prospects for European farming

were also much improved by the reduction of rates for carrying

maize on the railway, which from 1922 was run by

a

South African

director, advised by a settler-dominated council. From 1923 tariffs

protected wheat and dairy farmers, and in the same year the

legislative council set up a finance committee to approve the

budget; on this, settlers outnumbered officials by eleven to three.

In 1923—4 there was a sudden influx of new settlers: white

landowners increased by

one-half.

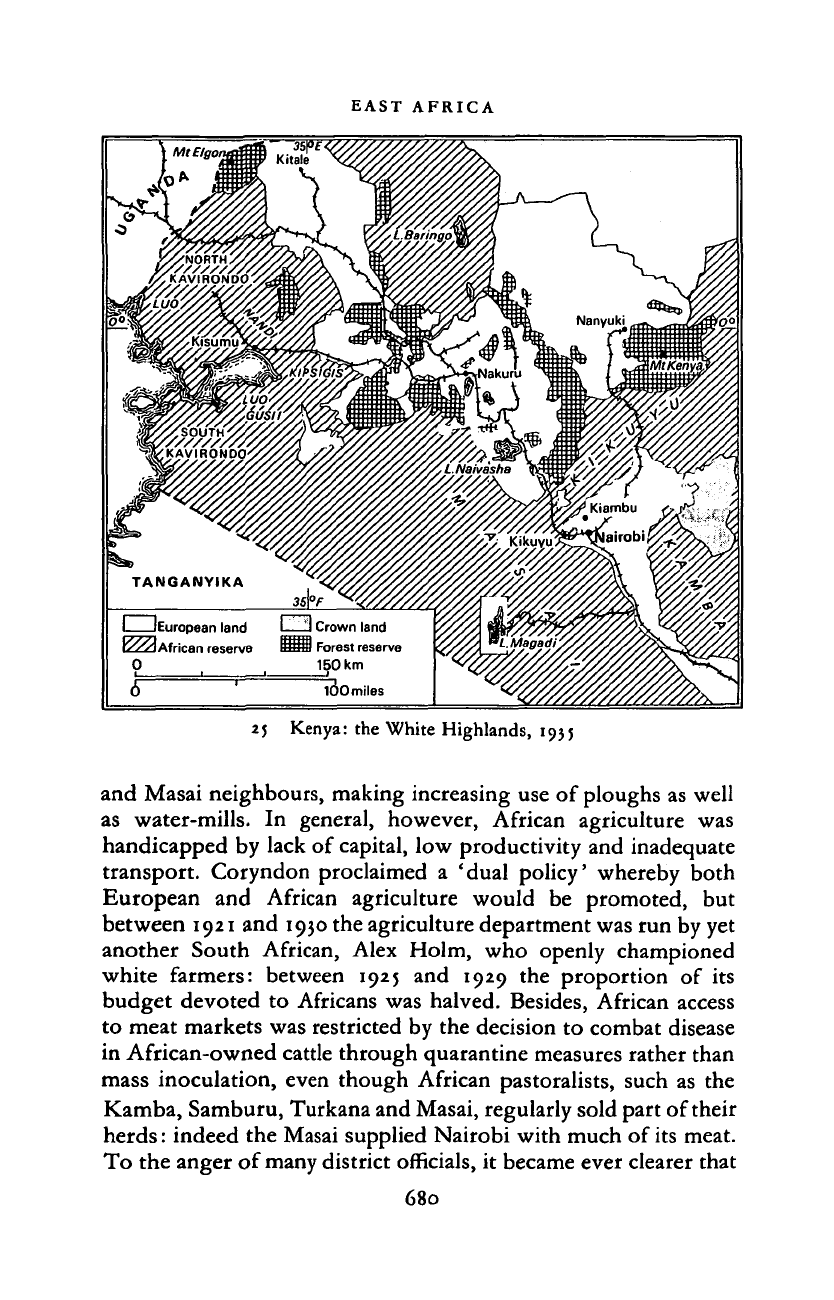

The middle 1920s were the best years in our period for

European farming in Kenya. There was little white immigration

after 1924, and in 1928 only one-eighth of the 'white highlands'

were cultivated. All the same, between 1920 and 1929 the area

under white cultivation increased between three- and four-fold;

the white population rose to 16,000. Export values rose fairly

steadily and in 1930 were almost twice those of 1921 (which had

reflected the height of the post-war boom). These exports were

mostly marketed by Europeans; the African contribution, which

had been greatly reduced by the war, rose to 25 per cent in 1925

but then declined, and consisted largely of hides and skins.

Between 1924 and 1927 the value of simsim exports, mainly from

Kavirondo and the coast, reached record levels but thereafter fell

away rapidly. Since 1916 Africans had been officially discouraged

from growing coffee, potentially the most lucrative export crop.

There was, of

course,

an important home market for food-crops;

the Kipsigis, for example, sold plenty of maize to their European

11

Indians in Kenya, Cmd. 1922 (1923), 1.

11

Meanwhile, some Indian seats were filled by nomination.

679

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EAST AFRICA

TANGANYIKA

I 'European land Crown land

CZZZlAfrican reserve WWII Forest reserve

0

| |

150 km

(5

'

100 miles

25 Kenya: the White Highlands, 1935

and Masai neighbours, making increasing use of ploughs as well

as water-mills.

In

general, however, African agriculture

was

handicapped by lack of capital, low productivity and inadequate

transport. Coryndon proclaimed

a

'dual policy' whereby both

European

and

African agriculture would

be

promoted,

but

between 1921 and 1930 the agriculture department was run by yet

another South African, Alex Holm, who openly championed

white farmers: between 1925

and

1929

the

proportion

of its

budget devoted

to

Africans was halved. Besides, African access

to meat markets was restricted by the decision to combat disease

in African-owned cattle through quarantine measures rather than

mass inoculation, even though African pastoralists, such as the

Kamba, Samburu, Turkana and Masai, regularly sold part of their

herds:

indeed the Masai supplied Nairobi with much of its meat.

To the anger of many district officials, it became ever clearer that

680

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

TERRITORIAL CONTRASTS

African taxation was being spent, not on African welfare but on

subsidies for frequently inefficient European farming: not only

through technical aid but through the cost

of

tariff protection,

road-building

and

uneconomic railway rates. Indeed, railway

costs were deliberately increased; the government raised new

loans

to

build expensive branch lines between 1924 and 1929

throughout the white highlands. One such line benefited Kikuyu

reserves, and the line to Kisumu was extended further into Luo

country,

but to

build

all

these railways

the

government was

obliged to enlist forced labour.

Thus in the course of the 1920s white settlers in Kenya came

to regard the colonial government

as

a friendly partner rather than

a potential enemy. Their hopes of territorial self-government had

been dashed

in

1923,

but

since then they had received many

material benefits from the imperial connection; besides, they were

given a large measure of local self-government on municipal and

district councils

set up in

1929. These favours

to the

settler

community were the price which Britain made Kenya's Africans

pay for the assurance that their interests would be 'paramount'

— that

the

colony would

not be

formally handed over

to

immigrants. For the time being there was no sustained African

criticism of this bargain. The demarcation of new reserves in the

mid-1920s temporarily allayed African fears for their land. By and

large, most articulate Africans during the 1920s were concerned

with the balance of power within their own communities rather

than at the centre. They were anxious to improve their access

to

European culture and

its

associated responsibilities,

but

they

sought this

by

exploiting local tensions and solidarities:

as in

Tanganyika, the most ardent ' improvers' were among the most

dedicated ' tribalists'.

Once

the

agitation

of

1922 had subsided,

it

was Christian

missionaries and government-appointed chiefs, quite as much as

settlers, who came under attack from African teachers and farmers

in central and western Kenya. In 1925 the government introduced

partly elective local native councils (LNCs), which obliged chiefs

to share power with their literate subjects. The councils were soon

used

to

press home the attack on missionaries, whose primary

schools failed to satisfy African demands for education that would

fit

them for leadership. In 1926, with government aid, Protestant

missionaries opened Alliance High School in Kiambu, but what

681

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EAST AFRICA

many Africans wanted was government schools in which mission-

aries would

no

longer be able

to

interfere with African customs,

an especially sore point among the Kikuyu. The Kikuyu Central

Association (KCA), formed

in

1924, was devoted not only

to

the

cause

of

higher education and the redress of economic grievances

but

to the

defence

of

Kikuyu culture,

and it

strove

to

promote

a sense

of

Kikuyu unity

as a

basis

for

communal progress. Thus

the conflict with

the

missions

in

1929 over

the

Kikuyu practice

of ditoridectomy crystallised aspirations both towards freedom

of cultural choice

and

towards

a new

sense

of

ethnic loyalty.

It

was

no

paradox that

in the

same year Kikuyu LNCs raised over

£20,000

to

build their own schools while Johnstone (later Jomo)

Kenyatta, secretary

of the KCA,

editor

of the

country's first

African newspaper and

a

champion

of

ditoridectomy, called

for

'a methodical education

to

open

out a

man's head'.

13

Uganda

In 1918 there

was

still

no

official agreement

as to the

relative

importance

of

African

and

European enterprise

in

Uganda's

future. But the hundred-odd European planters were very hopeful.

During the war they had mostly prospered. Exports of coffee and

rubber substantially increased, both

in

value

and in

bulk. They

still formed only a small proportion of total exports (together they

amounted

in

value

to 10 per

cent

in

1918-19),

but in

1920

the

planters were sufficiently encouraged

to

press, like white farmers

in Kenya,

for

special assistance from government

at

the expense

of African producers. They

had

friends

in

high places:

the

chief

justice, Morris Carter,

and a

South African governor, Robert

Coryndon (1918-22).

In

1921 Coryndon introduced

a

legislative

council

in

which five officials were joined

by two

nominated

Europeans;

one

nominated seat

was

provided

for the

Asian

community, who until 1926 boycotted

it in

protest.

In the

same

year, Churchill,

as

colonial secretary, approved long-standing

proposals

to

make available

for

alienation large areas

in

the three

kingdoms bordering Buganda.

These soon proved hollow victories,

for

meanwhile export

prices

had

collapsed.

The

depression,

and the

East African

" Quoted by T. O.

Ranger,'

African attempts to control education in East and Central

Africa, 1900-19)9', Past

and

Present,

1965, 32,

67.

682

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008