Roberts A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: from 1905 to 1940

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

COLONIAL CONSTRUCTION

workers especially tended to be away from home just when they

were most needed, and cultivation suffered in consequence, thus

hastening the retreat of men from advancing tsetse frontiers.

The economic contrasts within and between African societies

were overlaid by cultural distinctions introduced or intensified by

Europeans. By 1914, mission schools had in some areas produced

a first

or

even second generation

of

African teachers, clerks,

evangelists and also

priests;

in Uganda, Bishop Tucker encouraged

African leadership in the Anglican Church, in which 33 Africans

had been ordained by 1914. Many of these educated men were the

children

of

chiefs: literacy, like cash crops, could give new

strength to an old regime; yet schools also opened new paths of

advance to the hitherto unprivileged. To a large extent, of course,

the advance of cash-crops and literacy went hand in hand: Ganda,

Luo and Haya farmers were best able to pay the fees charged by

most mission schools, and many also made voluntary contrib-

utions. As yet, the Bible was the one book to make much impact

even on the handful of newly literate Christians, though already,

among the Ganda, this had influenced ideas of history as well as

religious

belief.

There was no challenge

to

the colonial order from educated

Africans, though

in

1914,

in

central Nyanza, the Nomia Luo

Mission was founded to build schools free from white missionary

influence. Violent resistance came from the grass-roots: most

fiercely in the Maji Maji rising

of

1905, but also in the Nyabingi

movement in south-western Uganda, and in 1914 from the Gusii

in South Nyanza and the Giriama on the coast. Central to each

of these was

a

local religious cult; in the case of Maji Maji, this

briefly united

a

huge area in common ritual and action, but the

rebels aimed at

a

very local, small-scale independence. The terrible

vengeance wrought by the Germans after Maji Maji made the facts

of European power more starkly plain

in

their territory than

anywhere else in East Africa. Yet neither there nor elsewhere was

this power passively accepted. Many opposed the extortion

of

unfree labour by deserting from recruiters' gangs or their place

of work.

In

German territory, especially

in

the north-east and

south-east, Islam gained much wider adherence than Christianity.

3

And as horizons expanded, new forms of solidarity were taking

shape. The colonial towns were racially segregated (for Indians

3

See chapter

4,

pp.

198,

Z13.

663

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EAST AFRICA

as well as for Africans) but they were nonetheless windows on

a wider world. They were still small, but growing fast: by 1911,

there were 17,000 people in Nairobi and 21,000 in Dar es Salaam.

Most of the Africans were probably short-stay migrants, but they

were likely to return home with a keener sense of ethnic identity,

as well as experience of a new kind of poverty and a better

acquaintance with the immigrants from overseas.

THE FIRST WORLD WAR, I 9 I 4-I 9 I 8

The East African campaign

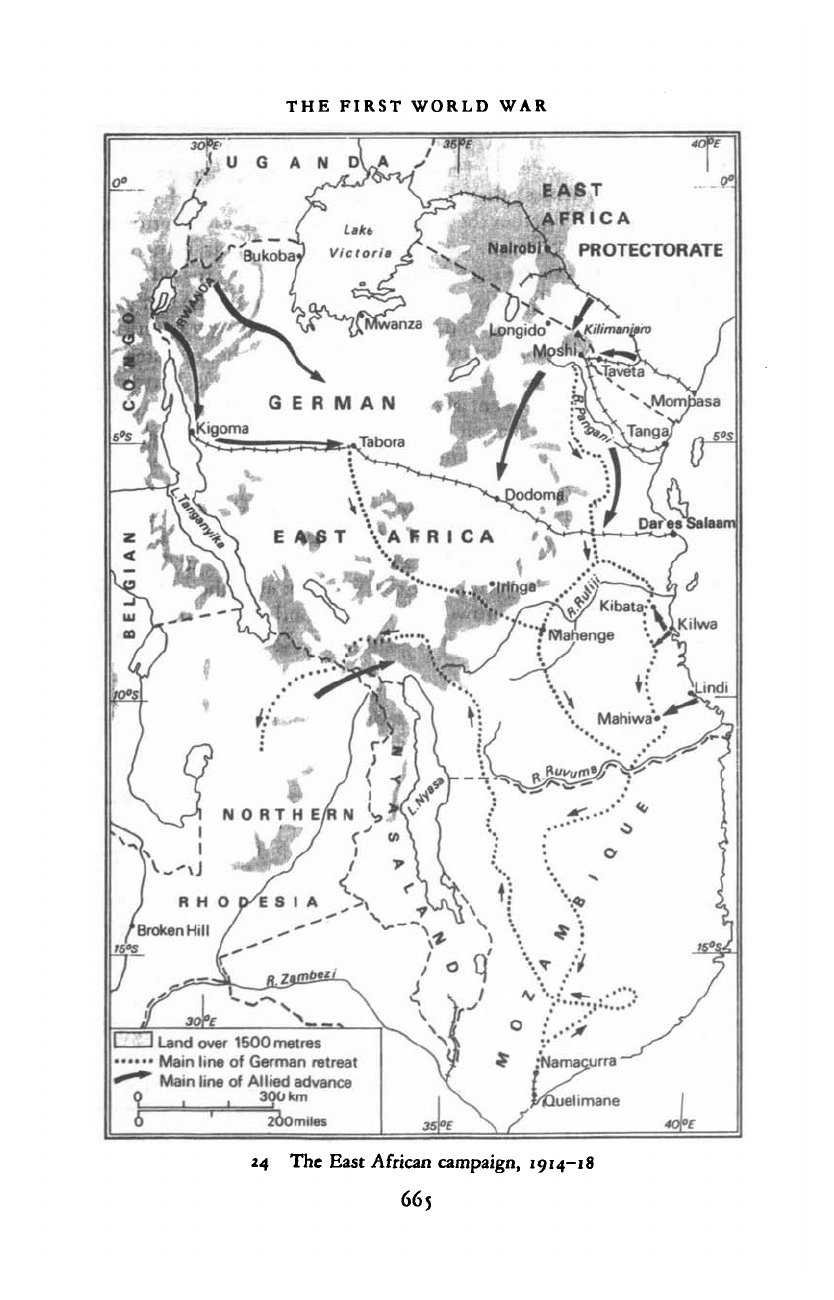

In August 1914, Britain and Germany went to war. The German

government had no intention of fighting in East Africa. There,

its defence force

(Schuts>truppe)

was precisely that: 218 Europeans

and 2,542 askari (African soldiers) faced 73 Europeans and 2,325

askari in the King's African Rifles, drawn from the East Africa

Protectorate, Uganda and Nyasaland. Schnee, the German gover-

nor, thought his colony indefensible and hoped to preserve

neutrality. But the

Scbut^truppe

commander, Colonel Paul von

Lettow-Vorbeck, considered it his business to divert enemy

troops away from the conflict in Europe. The British, for their

part, were mainly concerned to prevent German warships from

threatening communications with India, and at first the India

Office took charge of the war in East Africa. On 8 August, the

British navy shelled a wireless station near Dar es Salaam.

Lettow-Vorbeck, in defiance of Schnee, promptly grouped his

forces near Kilimanjaro and captured Taveta, just inside British

territory. The British then set about the invasion of German East

Africa. However, they grossly underestimated the fighting power

of Lettow-Vorbeck's African troops and sent against them some

of the weakest units in the Indian army, under mediocre comman-

ders.

On 3 November part of this force landed at Tanga but

withdrew after heavy losses, while the rest were rebuffed far

inland, at Longido.

Soon after these reverses, the British War Office took control

of operations in East Africa but gave them low priority and a long

stalemate ensued, though in June 1915 the British captured

Bukoba, on Lake Victoria. In July the Germans surrendered in

South West Africa; this released South African troops for use

664

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE FIRST WORLD WAR

\*A

15

R I C A

/•* "?/l

_J Land over 1500 metres

••• Main line of German retreat

"*" Main line of Allied advance

, 300km

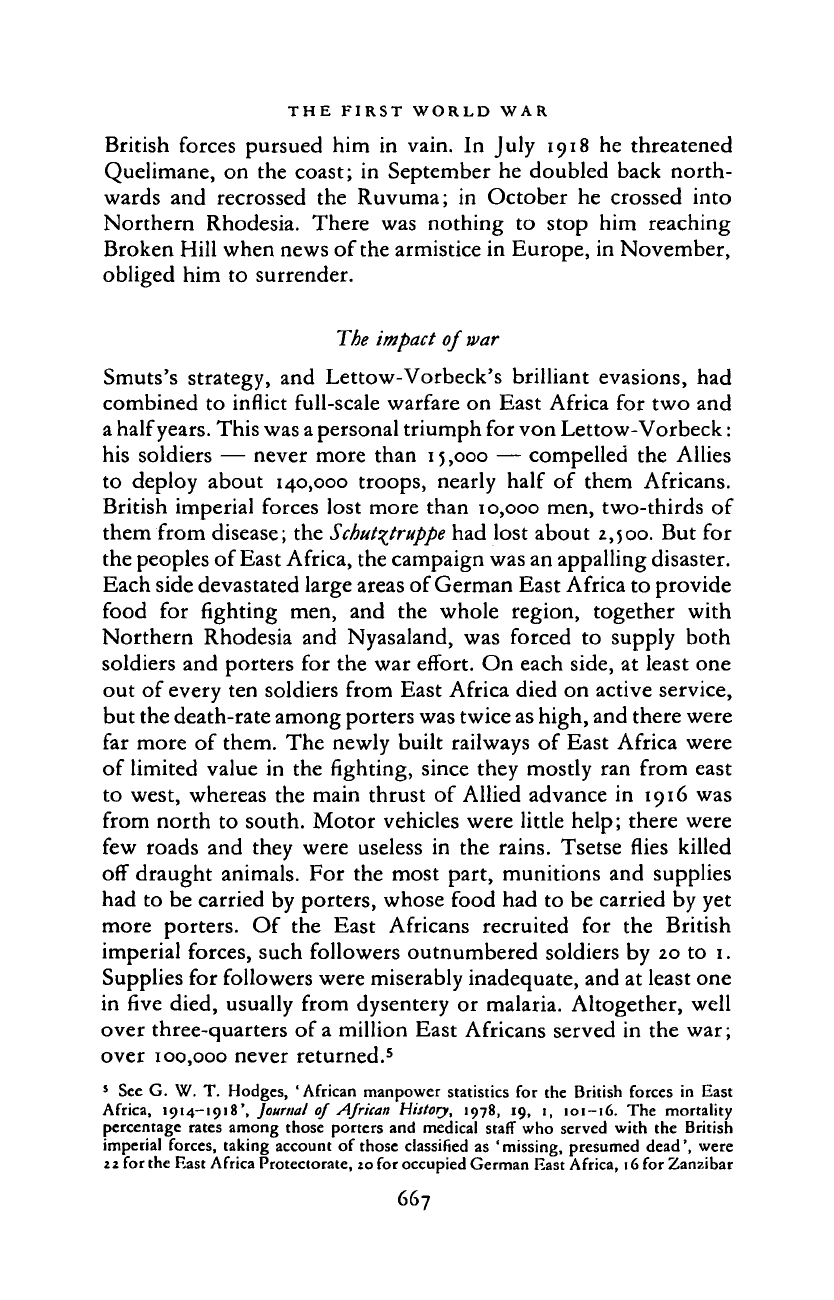

24 The East African campaign, 1914-18

665

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EAST AFRICA

elsewhere.

In

February 1916 General Smuts took command of the

British imperial forces

in

East Africa; these

now

included

the

King's African Rifles, British

and

Indian regiments,

and

white

South Africans. Together they outnumbered the forces of Lettow-

Vorbeck

by

nearly five

to

one.

In

March 1916 Smuts launched

a new invasion from the East Africa Protectorate. He crossed into

Tanganyika near Kilimanjaro and captured Moshi, but he had yet

to encounter the main German forces. Despite his greatly superior

strength, Smuts was reluctant

to

risk battle with them; instead,

he deployed

the

Allied forces

in an

attempt

to

encircle Lettow-

Vorbeck. One column went after the Germans towards the central

railway, while Smuts himself advanced down the Pangani valley;

he captured Tanga

in

July, and Dar es Salaam fell

in

September.

Meanwhile

the

British took Mwanza

in

July,

and

General

Northey, advancing from Northern Rhodesia

and

Nyasaland,

captured Iringa in August.

In

the west, the Belgians took Ruanda

in May and Tabora in September. The German garrison at Tabora

escaped and eventually joined Lettow-Vorbeck

at

Mahenge, near

the Rufiji valley. Smuts

now

tried

to

surround

the

Germans

by

taking Kilwa

and

moving inland,

but in

December

he was

checked

at

Kibata.

Smuts's elaborate design played into Lettow-Vorbeck's hands.

The Germans and their askari were masters

of

bush warfare and

drew their pursuers across rugged

and

thinly peopled country

during the worst of the

rains.

In October 1916a British intelligence

officer wrote

in his

diary, 'What Smuts saves

on the

battlefield

he loses

in

hospital,

for it is

Africa

and its

climate

we are

really

fighting, not the Germans. '

4

By the end

of

1916 the Allied forces

were gravely depleted

by

sickness,

and

most British, South

African

and

Indian troops were replaced

by

West Africans

and

new recruits to the King's African Rifles. Early in 1917 Smuts left

East Africa. Heavy rains delayed further operations,

but in

July

the British began

a new

advance inland from Kilwa

and

Lindi.

In October,

the

column from Lindi finally confronted Lettow-

Vorbeck

at

Mahiwa. This was the fiercest battle

of

the campaign.

Lettow-Vorbeck escaped into Mozambique,

but

with

a

much

reduced force:

his

colleagues from Mahenge surrendered rather

than starve. Lettow-Vorbeck

had

little ammunition left,

but for

another year he kept on the move in northern Mozambique, where

4

R.

Meinertzhagen, Army

diary tS?y—if26

(Edinburgh and London, i960), 200.

666

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE FIRST WORLD WAR

British forces pursued him

in

vain.

In

July 1918 he threatened

Quelimane, on the coast;

in

September he doubled back north-

wards and recrossed

the

Ruvuma;

in

October

he

crossed into

Northern Rhodesia. There was nothing

to

stop him reaching

Broken Hill when news of

the

armistice in Europe, in November,

obliged him

to

surrender.

The impact of

war

Smuts's strategy, and Lettow-Vorbeck's brilliant evasions, had

combined to inflict full-scale warfare on East Africa for two and

a half

years.

This was

a

personal triumph for von Lettow-Vorbeck:

his soldiers — never more than 15,000 — compelled the Allies

to deploy about 140,000 troops, nearly half

of

them Africans.

British imperial forces lost more than 10,000 men, two-thirds of

them from disease; the

Schut^truppe

had lost about 2,500. But for

the peoples of East Africa, the campaign was an appalling disaster.

Each side devastated large areas of German East Africa to provide

food

for

fighting men,

and the

whole region, together with

Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, was forced

to

supply both

soldiers and porters for the war effort. On each side, at least one

out of every ten soldiers from East Africa died on active service,

but the death-rate among porters was twice as high, and there were

far more

of

them. The newly built railways

of

East Africa were

of limited value in the fighting, since they mostly ran from east

to west, whereas the main thrust

of

Allied advance

in

1916 was

from north to south. Motor vehicles were little help; there were

few roads and they were useless

in

the rains. Tsetse flies killed

off draught animals. For the most part, munitions and supplies

had to be carried by porters, whose food had to be carried by yet

more porters.

Of

the East Africans recruited

for the

British

imperial forces, such followers outnumbered soldiers by 20 to

1.

Supplies for followers were miserably inadequate, and at least one

in five died, usually from dysentery

or

malaria. Altogether, well

over three-quarters of a million East Africans served in the war;

over 100,000 never returned.

5

s

See

G.

W.

T.

Hodges, 'African manpower statistics

for

the British forces

in

East

Africa, 1914-1918', journal

of

African History, 1978,

19, i,

101-16.

The

mortality

percentage rates among those porters and medical staff who served with

the

British

imperial forces, taking account

of

those classified

as

'missing, presumed dead', were

22 for the East Africa Protectorate, 20 for occupied German East Africa, 16 for Zanzibar

667

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EAST AFRICA

The mass conscription of Africans as porters had far-reaching

effects throughout East Africa. Many areas were virtually emptied

of men, and food-production was crippled. Women continued, as

always, to bear the brunt of sowing and harvesting as well as

grinding, but without men to clear new land they were often

obliged to cultivate existing plots to the point of exhaustion. Yet

it was just when the burden of war was heaviest that the region

suffered drought and disease on a scale which recalled the disasters

of the 1890s. Late in 1917 the rains failed throughout East Africa,

and they failed in Uganda a year later. Famine was widespread:

in the East Africa Protectorate it was partly relieved by food

imports from India and South Africa, but in parts of eastern

Uganda, in 1918-19,

one m

f°

ur

ma

y

nave

died of starvation,

while in Dodoma district one in five died of famine between 1917

and 1920. Lack of food lowered resistance to diseases spread by

returning porters. In 1917, at least 10,000 died in Uganda of

cerebro-spinal meningitis, while plague and smallpox also killed.

Towards the end of 1918, East Africa succumbed to the influenza

pandemic: this may have killed as many as 80,000 in German East

Africa, 25,000 in Uganda and 50,000 in the East Africa

Protectorate. One doctor reckoned in these terrible years that over

one-tenth of the Kikuyu people died of famine or influenza, or

while serving as porters. Yet this was not all: disease deprived

many of their chief store of wealth. Rinderpest, which had swept

northern Uganda in 1911, reappeared in western Uganda in 1918

and within two years killed over 200,000 cattle. Veterinary

surgeons would have saved them, but the war had stripped

governments of

staff.

Even then the cycle of destruction was not

complete: the death of people and cattle during the war meant

that large areas once cultivated and grazed now reverted to bush,

thus allowing the further advance of tsetse fly and sleeping-

sickness. In 1913 it had been reckoned that one-third of German

East Africa was infested by tsetse: by 1924 the proportion was

nearer two-thirds in what had become Tanganyika.

The disasters of the war years inevitably retarded the growth

of East Africa's export trade. Yet it continued, except in German

territory. There, many settlers had been ruined by the collapse of

and 8 for Uganda. About 22,000 African soldiers were recruited from the British East

African territories, of whom about 2,500 died; over 12,000 were recruited for the

Scbut^truppe,

of whom about 1,800 died.

668

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE FIRST WORLD WAR

rubber prices in 1913, when vast new plantations

in

South-East

Asia came into production. When war broke out, all exports were

thwarted by

a

British naval blockade; after the British occupation,

exports (chiefly of

sisal)

were resumed. In Uganda, cotton output

scarcely increased,

but

European-grown coffee ranked second

among exports in 1915-17, contributing

16

per cent, while rubber

exports steadily grew: Uganda's planters, unlike those in German

East Africa,

had

chosen

to

grow Hevea

brasiliensis,

the

same

high-quality rubber as that which came from South-East Asia. In

the East Africa Protectorate, hides and skins provided more than

a quarter of total exports in 1918, but so now did sisal: the coastal

plantations came into production just as the war began

to

boost

demand

for

rope and twine. Soda ash provided 15 per cent

of

exports: this came from European works

at

Lake Magadi,

to

which

a

branch line was built with

a

British loan just before the

war. Coffee exports had slowly advanced, but formed less than

10 per cent of the total.

The export production of the war years was encouraged by high

prices,' but import prices also rose, and in any case exports were

sustained, like the military campaign, by stretching resources of

labour to the limit. These pressures greatly increased the tensions

already inherent in East African society. Government and private

employers drew closer together

in

attempts

to

co-ordinate

the

extraction of yet more labour.

In

the East Africa Protectorate,

a

war council was set up in 1915 which was dominated by settlers:

this reduced carriers' pay and in 1916 strengthened legal controls

over labour;

in

the same year, African taxation was increased.

These measures maintained European production for the market

while crippling that of Africans. The effect was most marked

in

Nyanza Province, which before the war had been the main source

of export crops but which then was heavily drained of both men

and cattle.

It

must also be noted that during the European war

a small but ugly war was waged by both Uganda and the East

Africa Protectorate against Turkana herdsmen, whose raids

by

1917 seemed to threaten European farms. Between 1915 and 1918

some 800 Turkana were killed, while far more were starved into

submission: they lost 400,000 cattle to the British.

At home,

no

less than

on war

service, Africans suffered

growing deprivation and frustration. Yet war was also

a

great

teacher. Mass mobilisation swept African men into organisations

669

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EAST AFRICA

of

a

scale, complexity and discipline such as few had ever known.

There was an abrupt exposure to European technology: men were

trained

to

handle radios, rapid-firing guns and motor-vehicles,

while

a few

became NCOs

and

even warrant officers.

And

alongside

the

European hierarchy

of

military power Africans

created organisations

of

their own which mirrored

it:

the beni

dance societies. These

had

originated

on the

northern coast

around the turn

of

the century; the war sharpened the element

of military parody, increased the need

for

the mutual aid they

offered, and spread their popularity far inland, among both armies.

There were but two societies: the Marini

for

soldiers and

the

Arinoti for porters, but by the end

of

1919 both had branches in

all the main towns of East Africa and the Marini leader, a former

akida, issued commands throughout

the

region from

his

headquarters

at

Iringa: he was known as Bismarck. There was,

moreover,

at

least one field

in

which Africans were able

to

supplant European leaders during the war. Both sides interned

and deported missionaries of enemy nationality, and many African

congregations were left to fend for themselves. Where, as among

the Lutherans, there were no African priests, teachers took charge,

and under their guidance several young churches learned

self-

reliance. When missionaries came back after the war, they were

often slow to recognise such proof of African ability, but Africans

were now less willing

to

take

for

granted the need

for

white

leadership.

Thus for all the physical destruction of the war years, people

all over East Africa were discovering new powers within them-

selves and exerting them in spheres far wider than family, clan or

chiefdom. They were also increasingly familiar with the large-scale

structures of colonial rule. In the next few years, white men were

to take major decisions about the place of Africans in the colonial

order

of

East Africa, but Africans too had thoughts on this and

were soon to give voice to them.

TERRITORIAL CONTRASTS, 1918-1930

Between the war and the world-wide depression

of

1930, there

were substantial changes in the material basis of life in East Africa.

External trade increased very considerably, and the region shared

in technological innovations which were then transforming the

670

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

TERRITORIAL CONTRASTS

industrialised world. Most important, motor-transport became

cheap enough to make possible the large-scale movement of goods

and people away from the few railway lines.

It

was in this period

that large numbers

of

Africans became purchasers

of

imports,

especially hoes, bicycles, saucepans, boots and shoes, paraffin, salt,

tinned food, tea, sugar and cigarettes.

A

small

but

growing

number

of

Africans began themselves to engage

in

retail trade,

helped by savings from the sale of cash-crops and by skills learned

from immigrants. Greater dependence

on

external trade

heightened African sensitivities

to

economic fluctuations,

especially among teachers, farmers and traders who aspired

to

British material standards

of

living and increasingly compared

their own fortunes with those

of

their chiefs

and

those

of

immigrant communities. At the same time, governments inter-

fered much more than ever before: not only were their officials

more mobile, but rising revenues enabled their numbers

to be

greatly increased. This growth

in

economic and administrative

activity had the very important if unmeasurable effect of helping

to reverse the general decline of population which seems to have

been more or less continuous over most of East Africa from the

1890s to the 1920s. Mortality, disease and infertility were checked

by better medicine, hygiene and clothing, by famine

relief,

and

by the increased cultivation of maize and cassava. Yet the region's

modest growth

in

wealth after the war was distributed very

unevenly. This was partly due

to

growing divergencies

in

the

politics of the various East African territories.

In

the aftermath

of war, earlier assumptions were reappraised, and decisions were

taken which tended

to

sharpen territorial differences

in

social

policy. These decisions were prompted both by the immediate

effects of the war and by the impact of the economic depression

of

1920-1;

they were also influenced by competing pressures on

the British government from India and from British friends

of

South Africa.

Tanganyika

The effects

of

war were most obvious

in

the former German

colony. At the end

of

1918, the greater part of it was in British

hands;

the Belgians had retreated from Tabora in 1917, though

they still occupied the

far

north-west. The Peace Treaty with

671

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EAST AFRICA

Germany

in

1919 placed

the

territory under

a

mandate from

the

League

of

Nations.

The

Belgian share

of

this

was

confined

to

Ruanda

and

Burundi;

the

rest

was

assigned

to the

British,

who

named

it

Tanganyika Territory.

6

In

July 1922

the

terms

of the

British mandate were confirmed: Britain obtained full powers

of

legislation

and

administration;

it

was pledged

to

prevent slavery

(which

the

Germans

had

never abolished), forced labour

for

private gain, trade among Africans

in

arms and liquor,

and

abuse

of African land rights. Subject

to

these conditions,

the

territory

could

be

incorporated

in a

federation

or

customs union.

The stated

aim of

the mandate

was to

assure

the

primacy

of

'native interests',

but

there

was no

provision

for

enforcement.

The best safeguard

of

African liberties was provided not by paper

promises

in

Europe

but by

recent changes

in

Africa.

In 1914,

European settlers were well on the way to becoming the dominant

political force in German East Africa. The British invasion in 1916

obliged them

to

abandon farms

and

plantations,

and the

rubber

trade

had

already been crippled

by

competition from South-East

Asia.

Sir

Horace Byatt,

the

British civilian administrator, cleared

the country

of

German nationals between 1917

and

1922, when

the white population was half what

it had

been

in

1914. Several

estates were sold

or

leased, mainly

to

British firms, Greeks

and

Indians,

and

rubber estates were replanted with sisal. Exports

of

sisal were slowly resumed

but

hampered

by

lack

of

shipping,

and

the price fell

in

1921. Sisal remained

the

chief export,

but its

importance temporarily declined

in

relation

to

African-grown

crops,

mainly coffee

and

cotton,

but

also groundnuts, which

ranked second among exports

in

1921

and

1923. Whereas

in 1913

Europeans had contributed over half

the

country's exports,

in the

early years

of the

mandate well over half

was

produced

by

Africans. Still more important, the nature of European production

changed. By the early 1920s sisal was the only crop grown in large

quantities

by

Europeans,

and it

could only

be

grown

in

steamy

lowlands unsuited

to

permanent white settlement; besides, much

was produced

by

companies financed from abroad with

a

lesser

stake

in the

territory than independent planters.

The position of Europeans in Tanganyika was thus undermined

at

the

very period when Britain

was

framing

new

policies under

the mandate.

In

1921

the

Colonial Office agreed that Tanganyika

6

This partition thwarted South Africa;

see

above,

p. 57}.

672

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008