The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13: Republican China 1912-1949, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

SPONTANEOUS PEASANT AGITATION 3OI

Characteristics

The spontaneous peasant movements analysed above show three main

characteristics.

77

The first is the weakness of class consciousness among

the peasantry, a weakness illustrated by the comparative rarity and

traditional nature of the social movements directed against the wealthy.

Tenants usually acted alone vis-a-vis their landlords, and in fact might do

so in competition with one another. Quite apart from the fact that the

landlord who has remained in the village can be relied on for small

services, the tenant-farmers depend upon him for their land. The competi-

tion between them to obtain or retain the plot which will enable their

family to subsist seems to be more keenly felt than any sentiment of

solidarity among the exploited. Refusals to pay land rent were seldom the

result of a collective decision taken together by the tenants of one or

several landlords. More often, they were individual actions dictated by

necessity. In cases where landlords or the administration denounced such

refusals, it would usually be more accurate to speak of an inability to pay

the rent

—

an inability illustrated by the many instances of tenants taking

to flight at the approach of the date when the rent fell due.

78

Seven of

the 197 cases involving tenants recorded by two Shanghai newspapers

between 1922 and 1931 (above, p. 278) consisted of tenants committing

suicide in desperation at not being able to pay the rent.

79

Some of those

seven suicides, like the suicides of debtors at the doors of their creditors,

may have been motivated by a desire to make a pitiless landlord or agent

lose face. But the fact remains that it was, to put it mildly, a roundabout

way of expressing aggression towards the exploiter.

Of the representatives of the elite, it was the official, not the landlord,

who was the most common target. The spontaneous orientation of peasant

anger suggests that the peasants of Republican China were more conscious

of state oppression than of class exploitation. In this respect they were,

perhaps, simply continuing a tradition that dated from the imperial age

80

further reinforced by the abuses perpetrated by the warlords. The state

77

1

retain three

of

the

six

characteristics

I

have distinguished

in a

former study: 'Les paysans

et

la revolution: Chine 1919—1949', Politiqite etrangire,

2

(1968) 124-9.

78

A

special prison

for

tenant-farmers, visited

by

Ch'iao Ch'i-ming

in

about 1925, held fifteen

prisoners, five of whom were women who had been arrested

in

place

of

their husbands who had

fled. Each prisoner owed

on

average rather less than ^oyuan in rent: Ch'iao Ch'i-ming, Cbiang-su

Kun-sban Nan-fmg An-bui Su-bsien

nung-tien

cbib-tu

cbib

pi-cbiao i-cbi kai-liang

nung-tien

wen-ft Mb

cbitn-i

(A comparison of the farm tenancy system of K'un-shan and Nan-t'ung in Kiangsu and

Su-hsien in Anhwei, and

a

proposal on the question of the reform of farm tenancy), cited in NTCC

1.109.

75

Ts'ai Shu-pang, 'Tien-nung feng-ch'ao', 31.

80

Cf. Kwang-Ching Liu,' World view and peasant rebellion: reflections on post-Mao historiography',

J'AS 40.2 (Feb. 1981) 311.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

3°2 PEASANT MOVEMENTS

embodies the world outside the village, a world that the villagers have

the impression of supporting in return for nothing

—

which is not at all

that far from the truth.

The second main characteristic of spontaneous peasant movements is

their parochialism. In default of class consciousness, there was a sense

of belonging to a local community, which overrode distinctions of class.

It was this socially heterogeneous community that villagers sought to

protect against attacks and threats from outside. The parochialism of

peasant actions is, needless to say, attested by the frequent incidence of

vertical movements. By reason of the quasi-unanimity of local hostility

displayed against neighbours or strangers, these movements resemble

wars between different peoples rather than social warfare. As in a national

war (as opposed to a civil war), the natural enemy is not the privileged

member in one's community but the foreigner, in other words the member

of a different community - or, indeed, that community as a whole.

Even when there is no vertical movement, the peasants only take up

arms to defend strictly local interests. The quickest way to pacify a canton

that has risen up against heavily repressive troops is to transfer the soldiers

to a neighbouring canton, where they can pursue their abusive ways to

the detriment of other villagers. The same sacred egoism dictates the

attitude of a village which, in time of famine, has managed to preserve

adequate stocks of rice but refuses to sell any to the neighbouring village

whose inhabitants are dying of hunger.

81

In the refugee camps set up

following the great flooding of the Yangtse in 1931, the peasants angrily

took issue with the charitable souls who were determined to feed people

already too weak to survive: why waste precious grain?

The need to limit themselves to survival strategies, which dictated these

attitudes, also explains the third characteristic of peasant agitation, namely

its almost invariably defensive nature. The transition to illegality is simply

the last resort. During the famine of the spring of 1937 an official, who

expressed surprise that a Szechwan peasant had become a bandit instead

of continuing to cultivate his field, was told by that peasant: 'You will

find the explanation in my stomach.' And, sure enough, the autopsy

carried out after his execution revealed a stomach full of nothing but

grass.

82

Others would limit themselves to committing petty larcenies in

the hope of being arrested and fed while in prison.

83

Elsewhere, and for

the same reason, the police who come to arrest those owing taxes are

implored by the neighbours to take them to prison too.

84

Even more

81

Hstti Wu-bsi (The new Wu-hsi),

4

June 1932, cited

in

NTCC

1.425.

82

Fan Ch'ang-chiang, 'Chi-o-hsien shang

ti

jen' (People

on

the line

of

hunger), Han-bsueb jueb-k'an

(Sweat and blood monthly) 9.4 (July 1937) 125.

*>

Ibid.

IJI.

««

NTCC

1.426.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SPONTANEOUS PEASANT AGITATION 303

numerous (as in the case of forty to fifty peasants in two or three villages

of Lo-t'ien hsien, Hupei, in the spring of 1931) are those who beg district

officials to confiscate their land so that they will be delivered from the

obligation to pay a tax that is beyond their means.

85

The peasants may react vigorously to a new situation or an attack from

outside, but they never take the initiative. They are, so to speak, at the

disposal of their adversary. The external assailant may, at one time or

another or simultaneously, be represented by the authorities (increased

taxation, unpopular administrative measures), the landlord (insisting on

a pledge deposit or payment of rent following a bad harvest), the heavens

(a bad harvest or some other natural disaster), one's neighbour (vertical

movements), bandits - or the soldiers who come to repress the bandits.

The essential point is that the peasants themselves hardly ever take up

arms offensively with a view to improving their lot or, a fortiori, putting

an end to their exploitation. It is only when a situation has deteriorated

86

or when they feel threatened by some new measure (even if it is, in reality,

a reform) that the peasants rise up, with the sole aim of re-establishing

the former situation.

At the origin of every peasant riot or revolt there was nearly always

one particular innovation that was deemed intolerable. Far from attacking

the established order, of which the peasants were themselves the principal

victims, they would rise up in arms only to re-establish it, to right some

wrong or return to the pre-existing norm, which they were prone to

idealize. Unlike those who took part in large rebellions like those of the

Taipings or the ' masters' of certain secret societies, the peasants and the

leaders who organized the general run of revolts and riots in Republican

China (with the exception of the Communist Revolution, that is) do not

appear to have been inspired by any overall vision of society nor to have

questioned the bases of its organization.

The parochial and self-defensive nature of peasant disturbances are

complementary. To defend a local group (whose composition

is

more often

heterogeneous than homogeneous) and safeguard its precarious existence

are the aims of most peasant riots or revolts. In principle, such defence

85

Ch'en Teng-yuan, Cbtmg-kuo fien-fu sbib

(A

history

of

land

tax in

China),

17 and

TFTC 31.14

(16 July 1934)

no.

86

To

mention only

two

examples, remember

the

coincidence (noted

on p. 279)

between poor

harvests (which themselves reflect

the

meteorological situation)

and

heavy periods

of

agitation

amongst the tenant-farmers; exactly like the coincidence between agricultural crises and peasant

movements

in New

Spain

in the

eighteenth century

(cf.

Pierre Vilar, 'Mouvements paysans

en

Amerique latine',

in

Xllleme Congres international

des

Sciences Historiques: Enquite

sur Us

mouvements paysans Jans le

monde

contemporain, rapport gine'ral,

t2—f).

Second example: the frequency

of revolts against the army, which is much greater during the Sino-Japanese War than before

1937

(supra,

p. 193). It is the problem or scourge of the moment (not the desire or hope for

progress) that provokes the agitation.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

304 PEASANT MOVEMENTS

was no different from protecting the harvests against marauders or

defending oneself against raids by bandits. To stand up to the latter, the

villagers (or, to be more precise, the village landlords) were, given the

frequent inefficiency of the authorities, inevitably obliged to set up

self-defensive militia

{t^u-wei fuari)

or, when they were faced with larger

bands,

veritable village leagues

{lien-chuang

hut,

lien-ts'un

hut). The link

between self-defence and agitation, also discernible in the case of the Red

and Black Flags of eastern Kwangtung {supra, p. 297) is even more

evident when it is a matter of ' revolts of insecurity',

87

where resistance

to bandits precedes (and grows into) a riot or insurrection. As a general

rule,

the insurrection is organized by the same men (landowners or village

notables) who had earlier organized the self-defence.

This leads to three negative observations in conclusion:

1.

It is not the peasants themselves who organize the majority of

'peasant revolts'. Despite their diversity, most of these movements are

inspired and organized by the notables of the village, the canton

(hsiang)

or even the district (ch'u). What are generally referred to as peasant

disturbances should, strictly speaking, be called rural disturbances:

they often involve the rural community as a whole, not just the

peasants. The peasants who are involved provide most of the 'troops', in

other words, the masses to be manoeuvred by the organizers who, for

their part, seldom work the land with their own hands. Like the Fourth

Estate in France in 1789, the peasant rioters of Republican China are

dragged along in the wake of a different class.

2.

Whether 'peasant' or 'rural', these disturbances did not constitute

a movement. All that can be said is that a series of non-coordinated and

for the most part badly organized and ill-prepared local actions took place,

sudden flare-ups of anger or instances of ' fury', to borrow a term used

in connection with an earlier period.

88

These presented little threat to the

authorities. While the behaviour and weapons of the Chinese peasants of

the twentieth century remained close to those of their ancestors of the

seventeenth century, the central government had at its disposal the arms

and means of transport and communication of the twentieth century. The

rebellious peasants and the forces of order were to say the least unevenly

matched. The local riots so swiftly repressed do not represent the

87

I borrow the expression from the French historian Yves-Marie Berce, who analyses a similar

process in seventeenth-century France: 'the duty of the people of the low-land to unite in the

face of enemies, looting soldiers or bandits can easily change into a riot against the soldiers of

the king'

(Croquants

et

nu-pieds),

84-5. In relation to China, cf. Bianco, 'Peasant self-defence',

215-18 (and 222-4 f°r the implications of the defence of the group), and above all chapter 5 in

Elizabeth Perry's

Rebels,

which is entitled, precisely, ' Protectors turn rebels'.

88

Roland Mousnier, Fureurs pajsannes: Us pay sans dans Us revokes

du

XVlIeme siecU (France, Rjtssie,

Chine).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PEASANTS AND COMMUNISTS 3OJ

equivalent of a 'peasant movement', then. Their multiplicity and their

recurrence suggest a discontent both widespread and persistent that is

often postulated but for which there is hardly any written evidence. It

was a discontent that the Communists were to express and exploit in their

own fashion.

3.

Finally, the typology that we have suggested with regard to the

targets of these peasant struggles would not have made much sense to

those who took part in them. Whether the peasants came to grips with

bandits, soldiers, or even tax-collectors, they felt that they were defending

themselves against an assailant, a foreign element that preyed as a parasite

upon the social body of the village. As we have noticed, the state often

symbolized such a parasite. If the Chinese peasantry did harbour a certain

revolutionary potential at the time when the Communists set about

leading it into the revolution, this potential consisted almost entirely in

the fact that the rural population was alienated from the state (and from

the society at large that was ruled by the towns). It lay in the confused

but deeply rooted and tenacious feeling that the state was alien to the

villagers, that what it embodied was, precisely, the external world which

exploited and oppressed the closed world of the village.

89

The Communists

achieved the tour

de force

of turning this potential (just one possibility

among many others) into action, in the process overcoming difficulties

that at first sight appeared insurmountable.

The difficulties were proportionate to the vast distance that separated

the way the peasants behaved (and, left to themselves, would have

continued to behave) from what the Communists in the end made them

achieve. Or, to put it another way: the distance between local self-defence

and revolutionary action, which implies an overall ambition and an

offensive strategy. To tell the truth, the Communists did not need to get

their peasant troops to cover the whole of that distance. The strategy

continued to be their concern alone. They used this peasant material to

create the rank and file of the revolution: no more, no less; but that was

in itself a considerable achievement.

PEASANTS AND COMMUNISTS: THE UNEQUAL ALLIANCE

'An utter fantasy' is one scholar's verdict on the famous Report on the

peasant movement

in

Hunan

which Mao wrote after carrying out an inquiry

in his native province during the winter of

1926—7.

90

At the moment when

*» Migdal has produced an excellent analysis of this feeling in connection with traditional peasantries

in general: Peasants, 47.

50

Hofheinz, Broken vase, 35.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

306 PEASANT MOVEMENTS

the CCP were preparing to tackle the rural reconversion of their

movement, Mao's wishful thinking predisposed him to a dynamic view

of the agitation that was provoked by the arrival in Hunan of the armies

of the Northern Expedition. His description of reality is inseparable from

his creator's vision of what a skilful revolutionary leader might make of

the peasant material. The fact remains that, in effect, the action of the

peasantry of Hunan in 1926—7 (or, to be more precise, the various and

divergent activities of a minority of peasants, some of whom continued

to be manipulated by their traditional masters) justified neither the

enthusiasm that Mao expressed in his

Report,

after the event, nor the hopes

he had entertained before it. The graduates of the Canton Peasant

Movement Training Institute that were sent into Hunan were not

successful in stirring up the masses before the arrival of the Northern

Expedition. On the contrary, the increase in numbers, membership and

activity of the peasant associations were a direct result of the progress

and victories of the military forces. Although duly lauded by Chinese

Communist historiography, the rare cases of effective peasant participation

in the fighting were, with very few exceptions, of no strategic importance

at all: 'these fights were peripheral to the main war'.

91

Subsequently, the

lamentable failure of the Autumn Harvest uprising in September 1927

confirmed the unprepared state and uncombativeness of the peasant

armies.

92

In March 1928, over 200,000 rebellious peasants were incapable

of seizing the town of P'ing-chiang in eastern Hunan.

93

Still later (August

1928),

Mao suffered a defeat in Ching-kang-shan, after the 29th regiment

of the 4th Red Army had completely disintegrated in the course of a battle.

The peasants who made up the regiment were homesick and decided to

return to their native I-chang in southern Hunan.

94

These few examples

suggest that on the eve and in the early days of their agrarian saga, the

Chinese Communists could place very little reliance upon the peasant

soldiers, thanks to whom, twenty years later, they were to conquer the

whole of China.

" Angus W. McDonald Jr. Tie

urban origins

of rural

revolution,

268. See also 269-70 and more

generally pages 264-80; Hofheinz, 'Peasant movement', ch. 6; and Donald A.Jordan, The

Northern Expedition 194—8, 203, 227—8.

52

Roy Hofheinz, 'The Autumn Harvest insurrection', CQ 32 (Oct.-Dec. 1967) 37-87; 'Peasant

movement', ch. 7.

53

Hsing-buo liao-yuan, 1.431-43, cited

by Hu

Chi-hsi, UArmie rouge

et

Vascension

de Mao,

126,

n.

16.

84

Hu Chi-hsi, UArmie

rouge,

12.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PEASANTS AND COMMUNISTS 307

P'eng P'ai and

the

peasants of Hai-Lu-feng (1922-8)

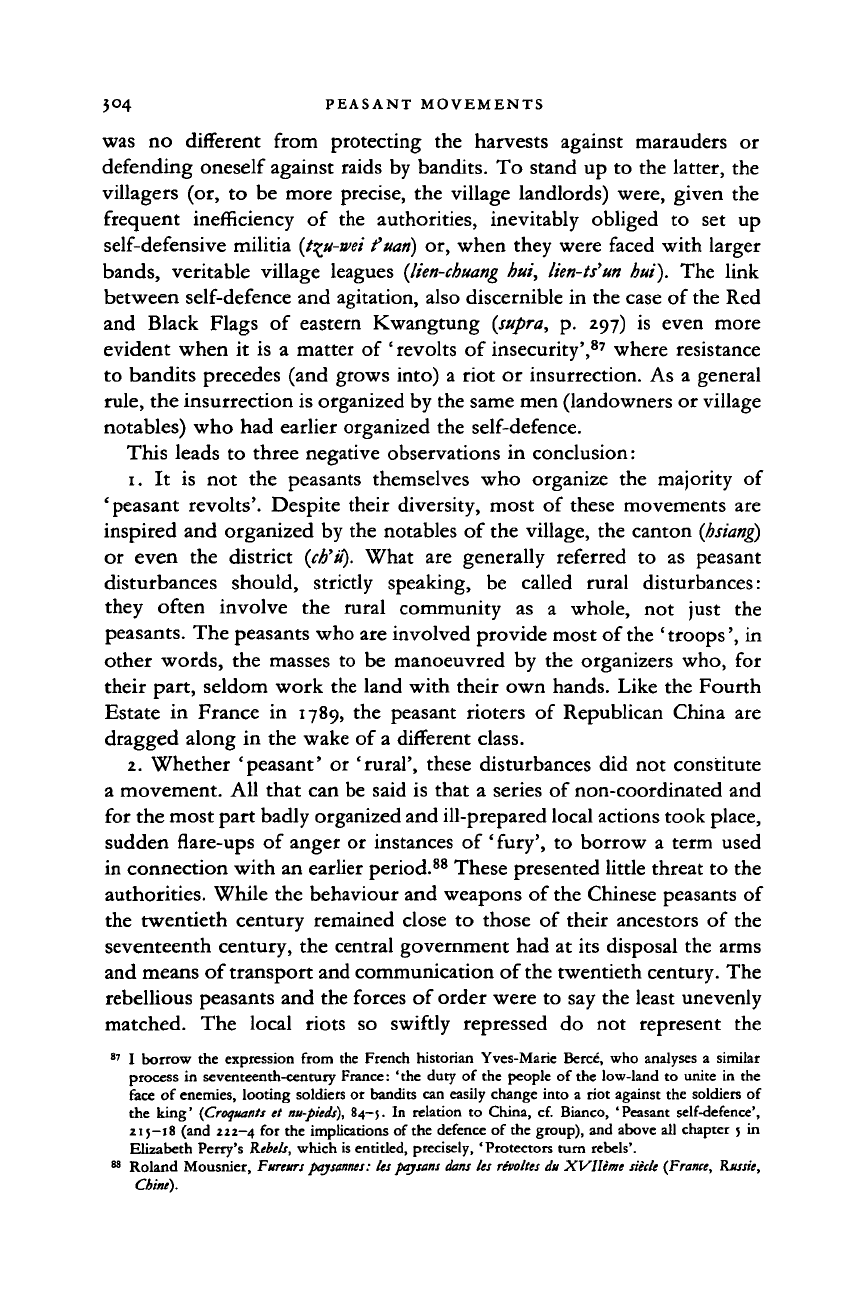

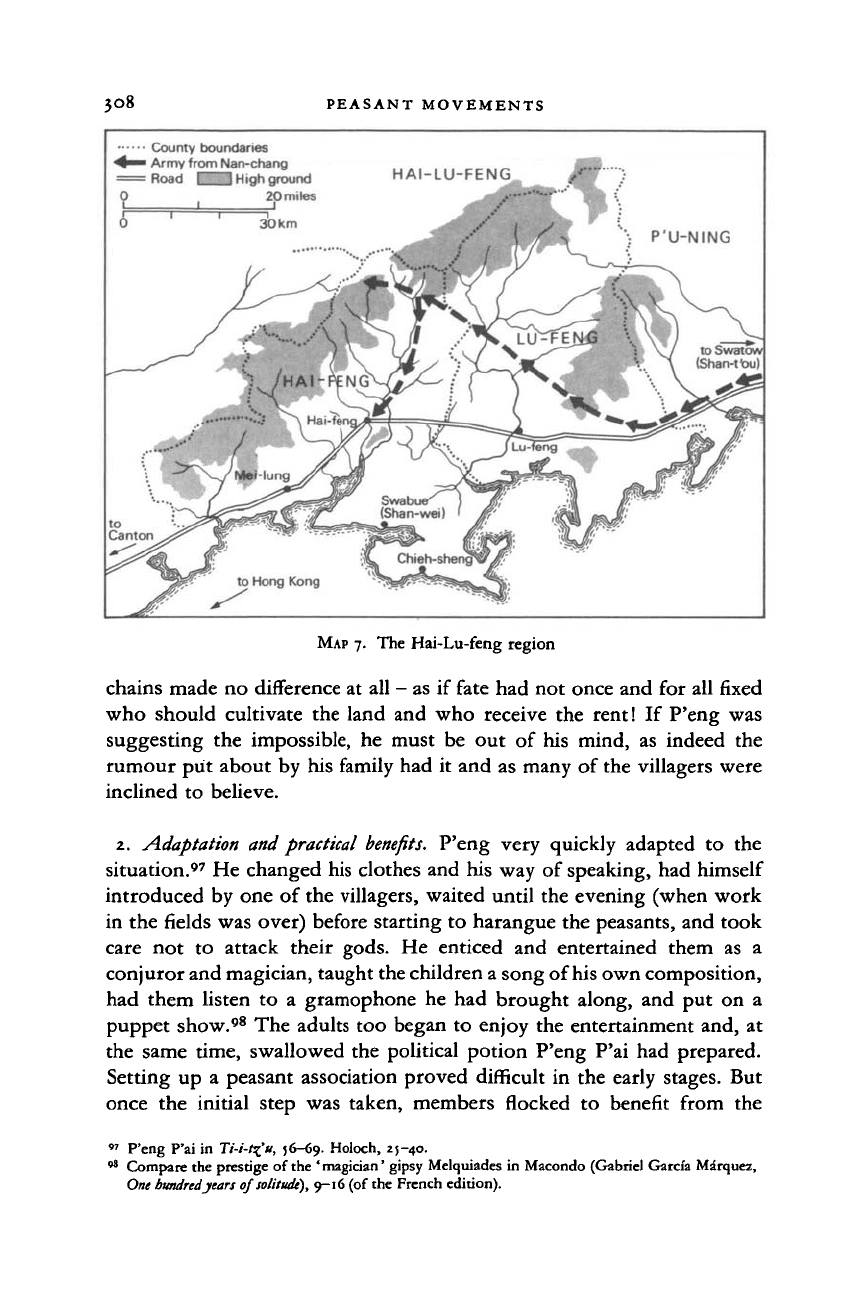

The first encounter between professional revolutionaries and villagers was

led by the pioneer of the Communist peasant movement, P'eng P'ai, in

two counties of eastern Kwangtung.

95

His initial success was remarkable.

The peasant associations that he founded as early as 1922 developed

vigorously. A few years later he maintained soviet rule over the two

densely populated counties of Hai-feng and Lu-feng (together known as

Hai-Lu-feng) for a period of several months (November 1927

—

February

1928),

at a time when Mao Tse-tung was still trying to establish himself

in the sparsely populated Chingkang mountains. But the difficulties that

faced the Communists in the mobilization of the Hai-Lu-feng peasants

prefigured those they continued to come up against later on. And the

methods to which they resorted prefigured the methods that they

continued to refine later on from Kiangsi to north Shensi. To link the

test case of Hai-Lu-feng with the two decades of' peasant' revolution that

followed, let us now summarize this first experiment, distinguishing (in

Chinese fashion) ten features of it.

1.

Initial

suspicion.

P'eng P'ai's first attempts were discouraging, revealing

the abyss that separated the villagers from a revolutionary whom they

quite rightly regarded as a member of the elite.

96

Doors were shut in his

face,

dogs barked at the intruder and the villagers turned away in alarm.

They suspected this well-dressed gentleman of having come from the town

to collect taxes or to insist on the repayment of

debts.

When P'eng replied

that it was up to the landlords to repay the tenant-farmers whom they

were exploiting, he elicited at first incredulity ('not to owe anything to

anyone would be good enough in

itself;

how could anyone possibly

owe me anything?') and then alarm from his questioners, who excused

themselves hurriedly and made off. Fear and suspicion of the stranger was

the initial reaction of the villagers, who had learned from long experience.

The fact that this stranger was urging them to free themselves from their

55

P'eng P'ai had probably not yet joined the CCP when he launched the Hai-feng peasant movement

and created the first peasant associations; nevertheless, he was an intellectual revolutionary at

grips with the problem of mobilizing the peasant masses. Furthermore, he was a member of

the parent organization, the Socialist Youth Corps, long before he joined the CCP. On the date

of P'eng P'ai's membership of the CCP, see Fernando Galbiati,' P'eng P'ai, the leader of the first

soviet: Hai-lu-feng, Kwangtung, China (1896-1929)' (Oxford University, Ph.D. dissertation,

1981),

205—4. This monumental thesis is the most reliable and by far the most detailed of the

many that are devoted to P'eng P'ai.

06

P'eng P'ai, 'Hai-feng nung-min yun-tung' (The peasant movement of Hai-feng), reprinted in

Ti-i-t^'u hio-mi

ko-ming cban-cbeng sbib-eb'i

ti nung-min jun-tung (The peasant movement during

the first revolutionary civil war period), 52-5. English translation by Donald Holoch,

Seeds

of

peasant revolution: report on tie Haifeng peasant movement by P'eng P'ai, 20-3.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

308

PEASANT MOVEMENTS

•*-

9_

5~

• County boundaries

• Army

from

Nan-chang

= Road

^H

High ground

20

miles

'

'

30km

^^BH^\Hai-Ten^

*^

_^

—

^

^^^'

to

Hong Kong

HAI-LU-FENG^,

—Hi

^i•

~2r •

^JJLU7

(Shan-wei)

1 /^'

k Chigvshenf^^'

")

P'U-NING

-^r x

H|\V toSwiTSw

MAP

7. The Hai-Lu-feng region

chains made

no

difference

at

all

-

as

if

fate had not once and

for

all fixed

who should cultivate

the

land

and who

receive

the

rent!

If

P'eng

was

suggesting

the

impossible,

he

must

be out of

his mind,

as

indeed

the

rumour put about

by

his family had

it

and

as

many

of

the villagers were

inclined

to

believe.

2.

Adaptation

and practical

benefits.

P'eng very quickly adapted

to the

situation.

07

He changed his clothes and his way

of

speaking, had himself

introduced

by

one

of

the villagers, waited until the evening (when work

in the fields was over) before starting

to

harangue the peasants, and took

care

not to

attack their gods.

He

enticed

and

entertained them

as a

conjuror and magician, taught the children a song of his own composition,

had them listen

to a

gramophone

he had

brought along,

and put on a

puppet show.

98

The adults too began

to

enjoy the entertainment and,

at

the same time, swallowed the political potion P'eng

P'ai had

prepared.

Setting

up a

peasant association proved difficult

in

the early stages.

But

once

the

initial step

was

taken, members flocked

to

benefit from

the

"

P'eng

P'ai in

Ti-i-tz^u,

56-69-

Holoch,

25-40.

98

Compare

the

prestige

of

the

'

magician'

gipsy

Melquiades

in

Macondo

(Gabriel Garcia

Marquez,

One

hundred yean

of

solitude),

9-16

(of

the

French

edition).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PEASANTS AND COMMUNISTS 309

services the association offered: free medical treatment, practical instruc-

tion, and arbitration to settle their quarrels. A pharmacy and a little clinic

managed by the association soon became so popular that it proved

necessary to check the membership cards, which were circulating from

hand to hand. The peasants learned how to write the names of their tools

and agricultural products and to check out the simple calculations hitherto

carried out unsupervised by the landlords and grain merchants. Not

content simply to settle disagreements relating to marriages, debts and

land ownership, the association also offered its members personal

protection, as a secret society would. The accidental drowning of a

child-fiancee living according to custom in the home of her future

father-in-law who was a member of the association, strengthened its

authority. P'eng and other members succeeded in intimidating and

turning back thirty or more assailants (relatives of the dead girl), who

had come to avenge the drowning.

To sum up this second phase: the revolutionary wins partisans to his

organization if not his cause by adapting himself to the world of the

peasants, sometimes at the cost of concessions, such as displaying tact with

regard to their superstitious beliefs, and by conferring upon a privileged

group (the members of the association) certain practical benefits which

answer their daily needs and preoccupations. A symbol of the practical

interest motivating the adhesion of the majority of those who allow

themselves to be won over could be the three dollars

{yuan)

which P'eng

P'ai lent to two of his earliest followers and which they then chinked in

the ears of their parents, who had been infuriated to see them leave their

work in the fields to follow a man of fine speeches.

3.

Fomenting class

struggle.

The sight of those three dollars mollified and

even delighted the mother of one of the earliest militants. But the fact

is that he and a handful of others followed P'eng P'ai because they believed

in him, not out of personal interest. It was the interest of their class (rather

than simply the interest of an individual or a group) that they wanted

to defend and promote by uniting around P'eng P'ai. He, for his part,

recognized this and forthwith addressed these first converts for social

reasons as 'comrades'. As for the mass of others, P'eng P'ai strove to

mobilize them with objectives that they would not spontaneously have

envisaged for themselves, and so drew the peasants into a veritable social

revolution.

The peasant association started by challenging the control of the

notables over commercial transactions; in the domain of practical benefits

referred to above, it set up its own scales in the public market-place in

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PEASANT MOVEMENTS

order to prevent the merchants from cheating when they weighed the

harvest. The association also won acquittal in a court of law for a tenant

who had refused to pay a rent increase and for five other farmers who had

declared solidarity with him. This solidarity, the first marker on the way

towards class consciousness, was actively encouraged, not to say provoked

by the association, which ended up by forbidding its members to rent any

field from which a tenant had been evicted by his landlord. It was a

disciplinary measure that reversed the normal situation of competition

between candidates for the tenancy of a field.

This solidarity and union were above all a means of pursuing an

offensive strategy with the aim of involving the peasants in new conflicts.

To this end the real state of class relations was deliberately blackened.

The association put about a simplistic chart which exaggerated the

landlords' exploitation of the peasants." The slightest conflict was seized

upon and deliberately exacerbated to bring into confrontation a minority

of exploiters and a mass of exploited peasants. The poverty and sufferings

of the peasants were described in apocalyptic terms. The devastation

occasioned by a typhoon in July 1923 was magnified so as to claim a 70

per cent reduction in land rents. Most of the tenant-farmers would have

been content to accept the traditional procedure: a rent reduction

proportionate to the damage suffered and the extent to which the harvest

had failed. Some landlords were equally prepared to negotiate, but the

tiny minority of intellectuals and peasants who controlled the peasant

association deliberately sought a confrontation.

I0

° A

hard core of landlords

had also concluded that the exorbitant claims of the peasant association

could no longer be tolerated. P'eng P'ai could congratulate himself upon

having divided the entire population of Hai-feng county into two classes:

on one side the peasants, on the other the landlords.

After the defeat of the peasant association, the changing fortunes of

war, punctuated by the two East River Expeditions in February and

October 1925, maintained the tension and eventually turned these two

classes into two enemy camps. Every swing of the pendulum brought

executions and sometimes a massacre that would subsequently have to be

avenged. In 1927 alone, two insurrections in April and September

prepared the way for the establishment of a soviet government in

November. Under this government, in effect a dictatorship, the question

of the peasants' commitment to the Communist cause was clearly no

longer in the same terms. Even if we allow for the element of constraint,

*» P'eng P'ai in Ti-i-t^u, 93-4. Holoch, 70.

100

Of the several opposed factions within the association, one at least favoured more flexible tactics.

The affair of the typhoon (see Galbiati, 311—14 and Hofheinz,

Broken

wave,

161-4) illustrates the

tactic of exploiting any circumstances to reach a new stage in the mobilization of the masses.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008