The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13: Republican China 1912-1949, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

SPONTANEOUS PEASANT AGITATION 29I

party

(lu-tui)

responsible for preventing their escape, attacking them with

their picks. In either case the trump card of the labourers was clearly their

number: albeit unwillingly, they represented a huge concentration of

workers who would normally have been much more widely dispersed. But,

in the first case, these peasants transformed into labourers would be trying

out a form of resistance with which they were unfamiliar (agricultural

workers themselves would hardly ever go on strike). In the second case,

in contrast, they would quite simply be anticipating (or reproducing) the

habitual pattern of battles between peasants and soldiers (or ' bandit-

soldiers').

51

During the spring of 1926, the Red Spears of western Honan (a secret

society identified as a movement of protection for the rural inhabitants)

are said to have massacred as many as fifty thousand, meaning a great

many, defeated soldiers.

52

Peasant self-defence against the soldiery had

been especially necessary and widespread in the warlord era. During the

Nanking decade, it continued to be so both in outlying provinces fought

over by quasi-autonomous warlords and also against units of 'bandit-

soldiers'

:

bandits who, it had been believed, could be domesticated if they

were enrolled in the regular forces but for whom the temptation to return

to their old ways was all the stronger given that their pay was hardly ever

forthcoming at the appointed time.

53

The Lung-t'ien incident (27-28 December 1931) illustrates just such a

case.

Because the exactions and brutality of the troops stationed in the

Lung-t'ien peninsula, Fu-ch'ing hsien, Fukien, had exceeded normal

levels,

several tens of thousands of peasants attacked 2,500 soldiers,

all

—

including their commanding officer

—

former bandits. These soldiers

had kidnapped villagers for ransom, auctioned off looted goods and

tortured peasants who resisted them. Finally, when a soldier had

attempted to cut off the finger of a woman who had not been quick enough

at removing the ring that he wanted and the incident had been followed

by collective rape, the peasants armed themselves better than usual (with

the inevitable clubs, daggers and pikes but with pistols and rifles as well)

and exterminated the soldiers. More than half the 2,500 men are said to

have perished. The peasants also suffered heavy losses but remained

masters of the field. They would agree to stop the fighting only when

given an official promise that the troops (or what was left of them) would

be transferred elsewhere. And, on 17 January 1932, reinforcements

51

Many cases

of

resistance

to

compulsory labour are recorded

in

NYTL 3.1025-8.

52

Tai Hsuan-chih, Himg-cb'iang-bui (The Red Spear Society), 192. On the Red Spears,

cf.

Elizabeth

Perry, Rebels, ch.

4.

53

Lucien Bianco,'La mauvaise administration provinciate en Chine (Anhui, 1931)'',Revue d'bistoire

modernt

et

contemporaine, 16 (April—June 1969) 306-7.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PEASANT MOVEMENTS

brought up from Foochow did indeed overcome the obstinacy of the head

of the vanquished troops (who had been holding out for a bribe in return

for agreeing to a transfer).

54

The exactions in which the regular army indulged from time to time,

although less frequent than those of former bandits integrated into the

army, were equally feared, sometimes even more than those of

the

bandits

whom the army was sent in to crush. These expeditions against bandits

(to whom the army would sometimes be selling arms and ammunition)

were seldom effective. Some resulted in even more farms and villages being

burned down and more peasants being massacred than in the course of

the raids by the bandits themselves.

55

Judging 'the remedy to be worse

than the original evil', the inhabitants of one zone of Fukien, which was

infested by banditry in 1932, sent off one petition after another requesting

(in vain) that the forces of order be recalled '

so

that they would be left

with only the bandits to fight'.

56

During the Sino-Japanese War, not only the provinces over which the

Kuomintang control was weak but also the very ones in which it was

entrenched, starting with Szechwan, became the scene of confrontations

between the peasantry and a predatory army. Thus, the peasants in the

Hsii-fu region (at the confluence of the Yangtze and the Min Rivers)

appealed to the Big Sword Society

(Ta-tao-hui)

which, one fine summer

morning in 194}, lost no time in dealing with a group of soldiers from

the 76th Army who were pilfering marrow. A ten-day battle ensued from

16 to 27 July (dubbed 'the Marrow war'). The outcome was that the 76th

Army, which had received reinforcements, put the Big Swords to

flight - and went on to loot more than ever on the pretext of looking

for Big Sword members.

57

Theft and extortion provoked fewer revolts than abuses in the conscrip-

tion system and the requisitioning of men for the army. In a famous

memorandum to Chiang Kai-shek, General Wedemeyer reminded him of

the scandalous trafficking and the terror inspired by conscription:

' conscription comes to the Chinese peasant like famine or flood, only more

regularly - every year twice - and claims more victims'.

58

On top of the

54

On

the Lung-t'ien incident,

cf.

the official correspondence

of

the American consul

at

Foochow

(Burke)

in

USDS 893.00/1181; (2; January 1932); 893.00/11837 (12 February 1932); 893.00 PR

Foochow/48

(13

January 1932) and /49 (10 February 1932).

55

One example (among dozens of others) concerning the region

to

the east

of

P'ing-tu (Shantung)

is described

in

USDS 893.00/8841, Webber (Chefoo),

2

April 1927.

55

Ibid.

893.00

PR

Foochow/57,

4

October 1932.

57

Ibid.

893.00/15141 (G.

E.

Gauss, Chungking,

29

September 1943).

58

Cited in Charles F. Romanus and Riley Sunderland, Stilwel/'s mission to China, 369. On the suffering

of the peasants conscripted

as

soldiers

and

inflicted

by

them

on the

civilian population,

see,

among others, Joseph W. Esherick, ed. host

chance

in China: the World War II

despatches

of

John

S. Service, 35-7; Theodore H. White and Annalee Jacoby, Thunder out of China, 132-40, 143-4;

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SPONTANEOUS PEASANT AGITATION 293

iniquities of a conscription system that hit only the poorest, there was

the periodic requisitioning of thousands and thousands of coolie labourers

who were herded about like cattle. The high mortality rate among

conscripts as well as coolies (often ill-treated and always ill-cared for) and

the brutalities and harassment inflicted upon civilians by the army over

eight years of the war, all exacerbated the peasants' traditional hatred of

the army. By the early 1940s, the iniquities

of

conscription and

the

exactions of the army had become comparable even to taxation as a factor

leading to peasant agitation. For

a

while,

it

seemed that

a

combination

of the two types

of

factors was prevalent: quite

a

few revolts were

provoked both by resentment

at

collection of land tax in kind and by

hatred of recruiting sergeants,

a

euphemism for the gangs who would

swoop down upon the cultivators in their fields and promptly tie their

hands behind their backs. Within less than a year (between autumn 1942

and summer 1943), peasant revolts of varying size and duration (some

involved fifty thousand men and lasted

for

several months) affected

virtually every province of China.

59

They were followed by another wave

in 1944, when Chinese soldiers fleeing before the new Japanese offensive

in Honan sustained numerous attacks from the survivors of the serious

famine

of

1942-3.^ The worst would befall soldiers who were isolated,

left behind or wounded. It was mainly in fiction that the peasants would

end up feeling pity for the plight of the soldiers (who were, after all,

peasants like themselves). Their initial instinct was to mete out to them

a slow and painful death.

61

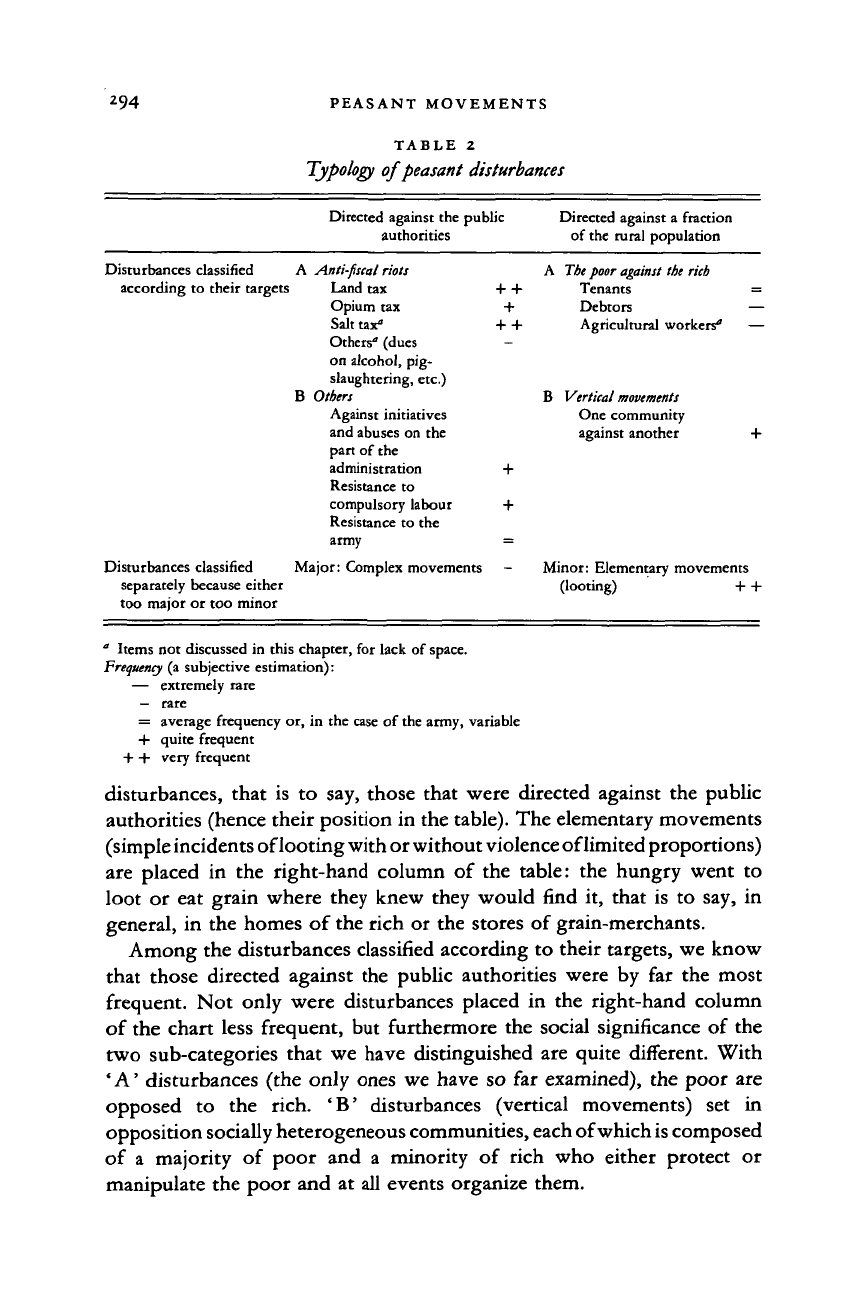

A schematic chart (table 2) sets out the various types

of

spontaneous

peasant disturbances. The affairs classified separately (in the bottom part

of the table) comprise on the one hand a very small number of complex

movements, lasting longer than the average disturbances; on the other

hand, a very large number of elementary movements as short-lived as they

were frequent. From the point of view of our first criterion (the target),

complex movements were, by definition, mixed. Even when not aimed

from

the

start against several different targets, they tended,

as a

consequence of their very duration, to acquire new ones as time passed.

Nevertheless, they were more closely related

to

the first category

of

and Lucien

Bianco,

Origins

of

the

Chinese

Revolution,

rfij-rp0,

15

5—7.

For

a

later

period,

see

Suzanne

Pepper,

Civil

mar in

China:

the political struggle

1941—1949,

i6}-8.

59

And in

particular:

the

east

and

west

of

Kweichow (USDS

895.00/14991;

15095),

north Szechwan

(ibid.

893.00/14997;

15022;

15026;

15055),

and

above

all the

Lin-t'ao region

in

southern Kansu

(ibid.

895.00/15009;

15033;

15047;

15074;

15107;

15112,

published

in

Esherick,

Lest

chance,

20-2).

60

USDS 893.00/6.1044

(Gauss,

Chungking,

10

June

1944),

13 and n. 26.

61

Chang

T'ien-i,

Ch'ou-ben

(Hatred).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

294

PEASANT MOVEMENTS

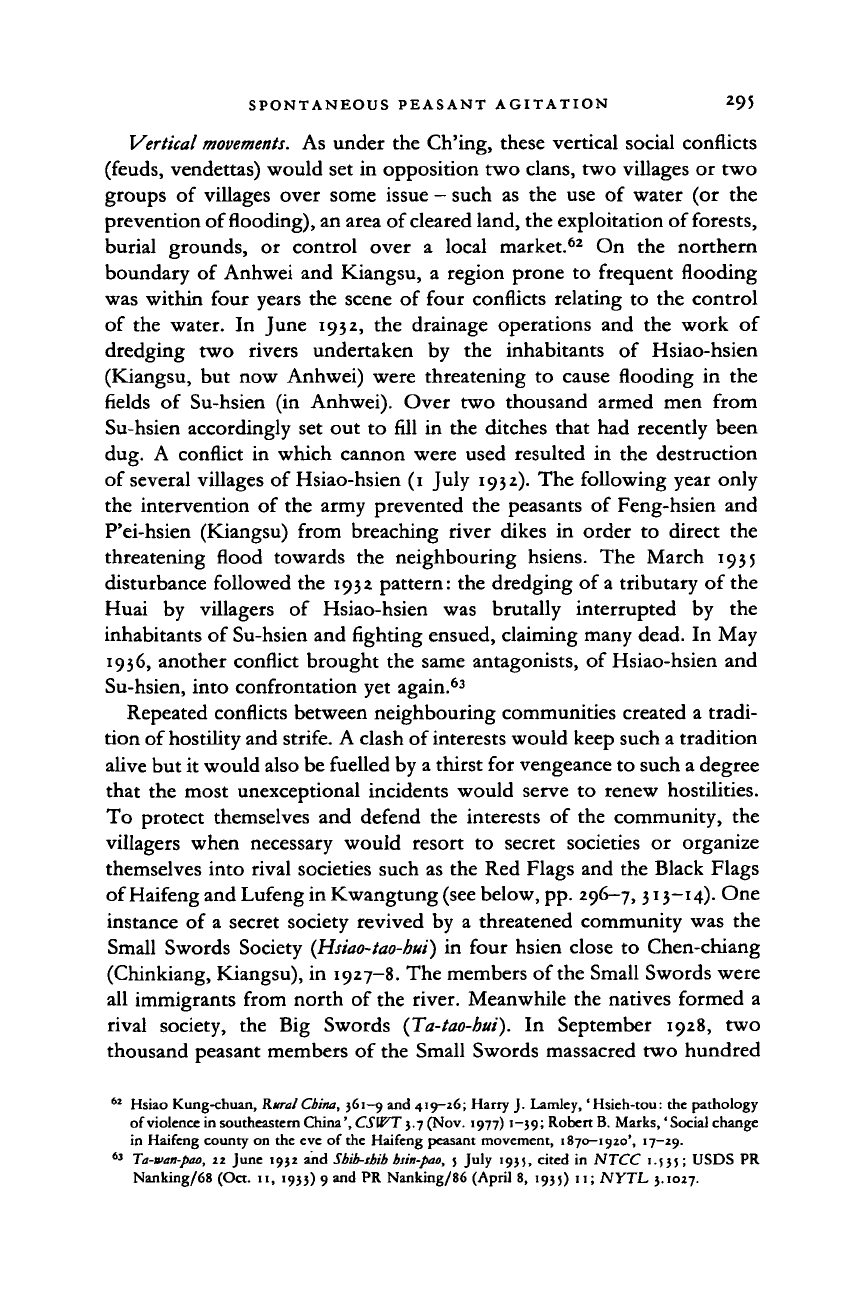

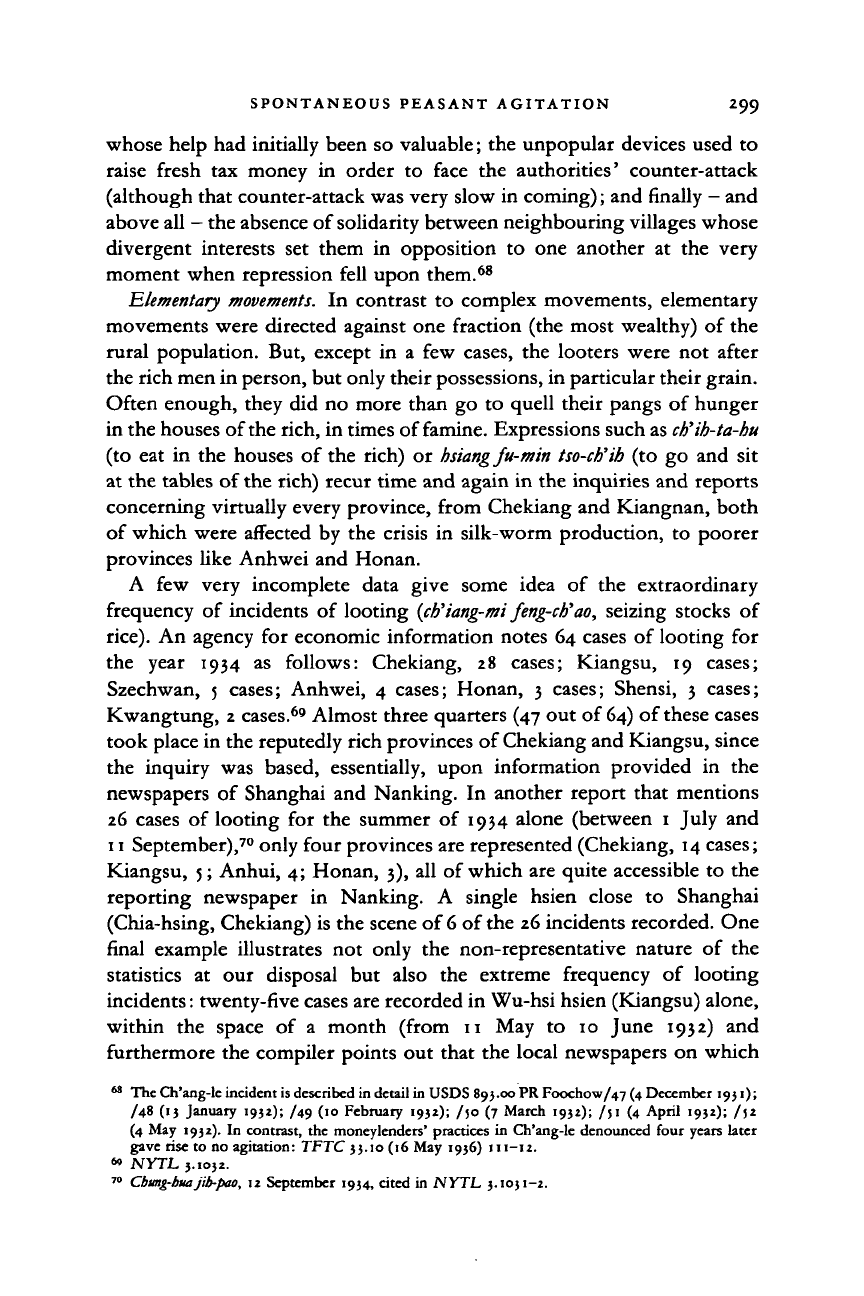

TABLE 2

Typology of peasant disturbances

Directed against the public

authorities

Directed against a fraction

of the rural population

Disturbances classified A

Anti-fiscal riots

according to their targets Land tax

Opium tax

Salt tax"

Others" (dues

on alcohol, pig-

slaughtering, etc.)

B Others

Against initiatives

and abuses on the

part of the

administration

Resistance to

compulsory labour

Resistance to the

army

Disturbances classified Major: Complex movements

separately because either

too major or too minor

A

The

poor against the rich

Tenants

Debtors

Agricultural workers"

B Vertical

movements

One community

against another

Minor: Elementary movements

(looting) + +

" Items not discussed in this chapter, for lack of space.

Frequency

(a subjective estimation):

— extremely rare

— rare

= average frequency or, in the case of the army, variable

+ quite frequent

+ + very frequent

disturbances, that is to say, those that were directed against the public

authorities (hence their position in the table). The elementary movements

(simple incidents of looting with or without violence of limited proportions)

are placed in the right-hand column of the table: the hungry went to

loot or eat grain where they knew they would find it, that is to say, in

general, in the homes of the rich or the stores of grain-merchants.

Among the disturbances classified according to their targets, we know

that those directed against the public authorities were by far the most

frequent. Not only were disturbances placed in the right-hand column

of the chart less frequent, but furthermore the social significance of the

two sub-categories that we have distinguished are quite different. With

'A'

disturbances (the only ones we have so far examined), the poor are

opposed to the rich. 'B' disturbances (vertical movements) set in

opposition socially heterogeneous communities, each of which

is

composed

of a majority of poor and a minority of rich who either protect or

manipulate the poor and at all events organize them.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SPONTANEOUS PEASANT AGITATION

2

95

Vertical

movements.

As under the Ch'ing, these vertical social conflicts

(feuds, vendettas) would set in opposition two clans, two villages or two

groups

of

villages over some issue

-

such as the use

of

water (or the

prevention of flooding), an area of cleared land, the exploitation of forests,

burial grounds,

or

control over

a

local market.

62

On the

northern

boundary of Anhwei and Kiangsu,

a

region prone to frequent flooding

was within four years the scene of four conflicts relating to the control

of the water.

In

June 1932, the drainage operations and the work

of

dredging two rivers undertaken

by the

inhabitants

of

Hsiao-hsien

(Kiangsu, but now Anhwei) were threatening to cause flooding

in

the

fields of Su-hsien (in Anhwei). Over two thousand armed men from

Su-hsien accordingly set out to fill in the ditches that had recently been

dug.

A

conflict in which cannon were used resulted in the destruction

of several villages of Hsiao-hsien (1 July 1932). The following year only

the intervention of the army prevented the peasants of Feng-hsien and

P'ei-hsien (Kiangsu) from breaching river dikes

in

order

to

direct the

threatening flood towards the neighbouring hsiens. The March 1935

disturbance followed the 1932 pattern: the dredging of a tributary of the

Huai

by

villagers

of

Hsiao-hsien was brutally interrupted

by the

inhabitants of Su-hsien and fighting ensued, claiming many dead. In May

1936,

another conflict brought the same antagonists, of Hsiao-hsien and

Su-hsien, into confrontation yet again.

63

Repeated conflicts between neighbouring communities created a tradi-

tion of hostility and strife. A clash of interests would keep such a tradition

alive but it would also be fuelled by a thirst for vengeance to such a degree

that the most unexceptional incidents would serve to renew hostilities.

To protect themselves and defend the interests of the community, the

villagers when necessary would resort

to

secret societies

or

organize

themselves into rival societies such as the Red Flags and the Black Flags

of Haifeng and Lufeng in Kwangtung (see below, pp. 296-7, 313-14). One

instance of a secret society revived by

a

threatened community was the

Small Swords Society

(Hsiao-tao-hui)

in four hsien close to Chen-chiang

(Chinkiang, Kiangsu), in 1927-8. The members of the Small Swords were

all immigrants from north of the river. Meanwhile the natives formed

a

rival society,

the

Big Swords (Ta-tao-bui).

In

September 1928,

two

thousand peasant members of the Small Swords massacred two hundred

62

Hsiao Kung-chuan, Rural China, 361—9

and

419-26; Harry

J.

Lamley, 'Hsieh-tou:

the

pathology

of violence

in

southeastern China', CSUTT

}.

7

(Nov. 1977) 1-39;

Robert

B.

Marks,' Social change

in Haifeng county

on the eve of the

Haifeng peasant movement, 1870-1920', 17-29.

63

Ta-van-pao,

22

June

1932 and

Sbib-sbib biin-pao,

5

July

1935,

cited

in

NTCC 1.535; USDS

PR

Nanking/68

(Oct. 11, 1933)

9

and PR

Nanking/86 (April

8, 1935) n;

NYTL 3.1027.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PEASANT MOVEMENTS

people and burned down six villages in Tan-t'u hsien, which had been

guilty of setting up local sections of the Big Swords.

64

The antagonism between the Small Swords and the Big Swords divided

each village down the middle, whereas the Red Flags and the Black Flags

of eastern Kwangtung represented veritable village alliances, formed in

the nineteenth century when new market towns had been established. The

new villages founded in the no man's land between two marketing

systems, and the weaker lineages that were situated on the periphery of

a market system and were seeking to escape from the domination of a

lineage solidly entrenched in the market town, tended to federate

themselves with the organization that was the rival of the one to which

their over-powerful neighbours belonged: namely, the Black Flags if the

closest market town was controlled by the Red Flags, and vice versa.

Thus,

by the end of the nineteenth century, Haifeng and Lufeng counties

were covered by a veritable (black and red) chequer-board of rival

organizations polarized into two great antagonistic

camps.

These organiza-

tions,

somewhat similar to Brecht's Round Heads and Long Heads, were

still very active during the 1920s.

65

The Red Flags and the Black Flags of eastern Kwangtung were thus

organized on a much larger scale and were potentially more destructive

than the sections of the Small Swords revived by the communities under

threat in Kiangnan. But this difference in scale should not mask the

identical nature of the vertical conflicts in which these various organizations

engaged. Although the demarcation line between Small Swords and Big

Swords divided each village, it did not separate the well-off or wealthy

homes from the poor ones. The real division, symbolized by the

opposition between the two secret societies, was between local folk and

the colonizers from elsewhere (a few leagues to the north) and their

children born locally but from families too recently arrived to be

integrated as yet; a body of foreigners which still, after one or two

generations, had not become assimilated.

66

Similarly, the conflicts which

had become endemic in eastern Kwangtung in the late nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries did not divide wealthy landlords from their tenants

or other landless peasants, but instead set in opposition rival communities

each with its own habitual cross-section of rich and poor. The leader of

the Red Flags or of the Black Flags was usually a wealthy man, who could

64

L. Bianco, 'Secret societies and peasant self-defence, 1921-193}', in J.Chesneaux, ed. Popular

movements and secret societies

in

China, 1X40—1)10, 221-2.

65

Marks, 'Social Change

in

Haifeng', 18-19 and 24-9.

66

Some immigrants really were foreigners:

at

Wan-pao-shan, eastern Liaoning,

in

July 1951,

500

Chinese peasants destroyed

a

dam and irrigation canal built by Korean immigrants. The Japanese

made

a

diplomatic incident out

of

it, two months before the Mukden coup.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SPONTANEOUS PEASANT AGITATION 297

use his fortune and influence to bribe or intimidate the officials and protect

his followers against taxation as well as against the enemy Flags. It was,

in effect, this protection that guaranteed the peasants' loyalty to their

particular Flag - protection which was even more necessary here than in

the rest of the Chinese countryside, on account of the insecurity fostered

by the activities of the rival Flags.

While conflicts between tenants and landlords may legitimately be

termed social, vertical conflicts only expressed local parochialism: the

adversary was not the rich but 'the others'. On occasion, the alien was

the worker (who was also a peasant) who had come from elsewhere; in

that case, the competition was not over land or water but over

employment. In

1921,

the China International Famine Relief Commission

made the mistake of employing on the construction of the Peking-Tientsin

road (destined, among other things, to make it possible to transport food

to areas in need) 2,800 workers recruited in Shantung. On the morning

when work started, the peasants of Hopei, helped by hooligans, attacked

these intruders and put them to flight, following which several hundreds

of local men demanded to be taken on in place of those they had

dispersed.

67

In early nineteenth-century France, artisan and worker

corporations used to inflame provincial and professional rivalries. They

put a brake on the development of class consciousness and undermined

the beginnings of a modern social movement. The struggles between the

Red and the Black Flags and the Big and the Small Swords, etc., a century

later, were to some extent a (Chinese and rural) replica of those French

confrontations between the

Gavots

and the

Devorants.

Complex

movements:

the example of

Cb'ang-le.

From the outset, the revolt

that erupted in November 1931 in Ch'ang-le (to the south of Foochow,

Fukien) was a double resistance: against both the army and taxation. In

January-February 1932, this movement targeted against the public

authorities was amplified by a vertical conflict, which precipitated the

eventual collapse of the movement. At the source of the disturbances was

a surtax on land imposed in the

hsiang

of Hu-ching (in Ch'ang-le county).

The purpose of this surtax was to help finance a plan for hydraulic

improvements undertaken by a naval detachment who were deeply

loathed by the villagers (they forced the latter to sow poppy seeds with

the sole aim of taxing the opium smokers). When the Hu-ching villagers

refused to pay the surtax, two naval battalions were rushed to the spot

to make them pay up. But the result was quite the opposite: the naval

battalions arrived on 4 November; on the 5th, the peasants declared war

on them.

67

John Earl Baker, 'Fighting China's famines' (unpublished manuscript, 1943), 147.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

298 PEASANT MOVEMENTS

This movement was not just complex; it was also better organized than

most peasant riots and revolts (which probably explains how it lasted so

long).

The villagers of Hu-ching, who since 1922 had been compelled to

serve in the local militia, were better - or at least less poorly - trained and

armed than their peers elsewhere. The leader of the revolt, Lin Ku-ju,

was none other than the commander of the militia of Hu-ching

hsiang.

Lin hired several graduates from the Pao-ting military academy to

complete the training of the militiamen and also a number of bandits to

whom he paid two months' salary in advance in return for their

commitment to serve right in the front line. During the night of 21

December, prepared and reinforced in this fashion and with a ten to one

superiority in numbers, the peasants of Hu-ching attacked the hsien yamen

of Ch'ang-le. The navy troops responsible for protecting it rapidly took

to their heels, abandoning arms and ammunition and the hsien magistrate

too.

This initial success made the rebels over-confident. They destroyed two

pumping stations installed by the navy and demanded that the latter depart

forthwith. Liu Ku-ju declared local autonomy and, without further ado,

took over the administration of the whole of Ch'ang-le county. He seized

all the revenues so as to cover his military expenses, retained and collected

the opium tax that he had been denouncing two months earlier and lifted

restrictions on the opening of opium dens and gambling houses. The

inhabitants of the other cantons

(hsiang)

of Ch'ang-le county, who had

not been subject to the surtax in the first place, were discontented at being

obliged to finance a struggle that was no concern of

theirs.

Furthermore,

the bandits who had been hired as mercenaries liberated common-law

prisoners and held up and robbed those fleeing on the roads. Clashes

ensued and soon turned into an

inter-hsiang

war at the very moment when

the authorities were sending in reinforcements. In February 1932, an

enemy

hsiang,

Hao-shang, captured Lin Ku-ju and handed him over to

the authorities, who executed him. On the 28th the navy attacked Hu-ching

and lent strong support to the inhabitants of Hao-shang when they came

to burn down the Hu-ching villages. By the time calm was restored, at

the end of March, forty villages had been razed to the ground and more

than seven thousand people were without shelter. During the agricultural

season of 1932, there was a wide band of uncultivated land between

Hu-ching and Hao-shang; but nobody dared venture into it to farm the

fields situated alongside enemy territory.

The Ch'ang-le revolt was exceptional in its complexity and organization

but in the end it foundered by reason of weaknesses that were not

exceptional at all: namely, the failure to maintain control over the bandits

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SPONTANEOUS PEASANT AGITATION 299

whose help had initially been so valuable; the unpopular devices used

to

raise fresh

tax

money

in

order

to

face

the

authorities' counter-attack

(although that counter-attack was very slow in coming); and finally

—

and

above all

—

the absence of solidarity between neighbouring villages whose

divergent interests

set

them

in

opposition

to one

another

at the

very

moment when repression fell upon them.

68

Elementary

movements.

In

contrast

to

complex movements, elementary

movements were directed against one fraction (the most wealthy)

of

the

rural population. But, except

in a few

cases,

the

looters were

not

after

the rich men in person, but only their possessions, in particular their grain.

Often enough, they did

no

more than

go to

quell their pangs

of

hunger

in the houses of the rich, in times of famine. Expressions such as

ch'ih-ta-hu

(to

eat in

the houses

of

the rich)

or

hsiang fu-min

tso-ch'ih

(to go

and

sit

at the tables of the rich) recur time and again in the inquiries and reports

concerning virtually every province, from Chekiang and Kiangnan, both

of which were affected

by

the crisis

in

silk-worm production,

to

poorer

provinces like Anhwei and Honan.

A

few

very incomplete data give some idea

of the

extraordinary

frequency

of

incidents

of

looting (ch'iang-mi

feng-ch'ao,

seizing stocks

of

rice).

An agency

for

economic information notes 64 cases

of

looting

for

the year

1934 as

follows: Chekiang,

28

cases; Kiangsu,

19

cases;

Szechwan,

5

cases; Anhwei,

4

cases; Honan,

3

cases; Shensi,

3

cases;

Kwangtung, 2 cases.

69

Almost three quarters (47 out

of

64)

of these cases

took place in the reputedly rich provinces of Chekiang and Kiangsu, since

the inquiry

was

based, essentially, upon information provided

in the

newspapers

of

Shanghai and Nanking.

In

another report that mentions

26 cases

of

looting

for the

summer

of

1934 alone (between 1 July

and

11 September),

70

only four provinces are represented (Chekiang, 14 cases;

Kiangsu, 5; Anhui, 4; Honan, 3), all of which are quite accessible

to

the

reporting newspaper

in

Nanking.

A

single hsien close

to

Shanghai

(Chia-hsing, Chekiang) is the scene of

6

of the 26 incidents recorded. One

final example illustrates

not

only

the

non-representative nature

of the

statistics

at our

disposal

but

also

the

extreme frequency

of

looting

incidents: twenty-five cases are recorded in Wu-hsi hsien (Kiangsu) alone,

within

the

space

of a

month (from

11 May to 10

June 1932)

and

furthermore the compiler points out that the local newspapers

on

which

68

The Ch'ang-le incident is described in detail in USDS 895.00 PR Foochow/47 (4 December 1931);

/48 (13 January 1931);

/49

(10 February 1932);

/50 (7

March 1932); /51

(4

April 1932);

/$2

(4 May 1932). In contrast, the moneylenders' practices

in

Ch'ang-le denounced four years later

gave rise to no agitation: TFTC 33.10 (16 May 1936) m-12.

«• NYTL 3.1032.

70

Cbmg-buajib-pao,

12 September 1934, cited in NYTL 3.1031-2.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

300 PEASANT MOVEMENTS

his information is based only mention two or three out of every ten cases

of looting that actually took place.

71

Another type of relatively serious and less ephemeral incident was

itinerant looting. Groups of as many as several hundred or even a

thousand hungry men, each equipped with a sack, would go from village

to village, seizing provisions.

72

Sometimes they would band themselves

into associations of the needy; the 'association of the poor people'

{ch'iung

kuang-tan

hut),

'

the company of starving people'

(cti"i-min-fuari)

or ' the

company of those who eat together'

(kung-ch'ih

fuan)."

13

But, for the most part, rice looting and rioting are typically elementary

movements, of limited scope and duration. In the spring, at the bridging

time between the harvests, a few hundred or even just a few dozen men

(and sometimes bands composed solely of women, old people and

children) would sally forth to make sure of a few days' provisions by

robbing a landowner, a shop, a depot or a junk. When the police or

authorities did intervene, it was sometimes to distribute provisions to the

looters, to get them to disperse more quickly.

74

Occasionally, the forces

of order would open fire but that was not the usual pattern. It was, in

principle, only when the starving peasants were forced to 'set out along

the dangerous road' (become bandits in order to survive) that repression

was unleashed.

75

These occasional looters were at pains to distinguish themselves from

professional bandits. Sometimes they petitioned the hsien magistrate to

be allowed to go looting, by reason of the exceptionally difficult

circumstances; or they would fall on their knees before the landowner

they were robbing, begging him to forgive them for the excesses to which

they were momentarily driven. Many of these looters took care to limit

their thefts to items of food and some were anxious to leave behind food

in sufficient quantities for the landowner and his family not, in their turn,

to go hungry.

76

" NTCC

1.425.

72

Examples relating to Honan and Hunan in NYTL 3.1030.

" Examples relating to Honan, Hupei, Anhwei and Kiangsu in NYTL 3.1033; to Szechwan,

ibid.

3.1029.

1*

The same procedure was followed during

the'

expensive bread riots' in France under Louis XIV:

cf. Yves-Marie Berce, Histoire

its

Croquants: etude des soulhemenli populaires au XVIIeme siecle dans

It tud-ouest de

la

France, J48.

75

For an example in eastern Szechwan, see NYTL 3.1029-30 (troops of warlord Yang Sen

sent against starving peasants turned bandits).

76

Cf. an

example

in

Wu-hsi

in

June 1932 (Htin-cb'uang-tsao (New creation) 2.1-2, July 1932, cited

in NTCC 1.428).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008