The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13: Republican China 1912-1949, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

HIGHER EDUCATION AND NATION-BUILDING 39I

government also promoted a national system of romanization for writing

Chinese in the Latin alphabet. Meanwhile a national commission on

compilation and translation had for some years been working out standard

Chinese equivalents for foreign technical terms in order to facilitate the

absorption of modern technology.

One main educational objective of the Nationalist government was to

standardize programmes of study in the universities. Beginning in 1933,

ordinances were issued to govern such matters as required courses,

electives, and procedures for college entrance examinations. In the last,

limits were placed on the number of candidates for the liberal arts

disciplines, so as to encourage more enrolment in the natural sciences and

technology.

80

Although the restructuring of academic programmes had

not yet been completed by the time war broke out in 1937, the

government's efforts were beginning to bear fruit: according to Ministry

of Education statistics, in 1930 a total of 17,000 students graduated in

liberal arts programmes as compared with a little over

8,000

in the areas

of agriculture, engineering, medicine and the natural sciences combined,

81

but by 1937 the figures were 15,227 for the liberal arts, and 15,200 for

science and technical disciplines.

82

For learning beyond the bachelor's degree, the Ministry of Education

in 1933 promulgated provisional regulations for the organization and

operation of postgraduate schools to be established within existing

universities with a capacity to award the master's degree. To be eligible

for registration with the Ministry of Education as a duly constituted

postgraduate school

(jen-chiuyuan),

the institution must comprise at least

three disciplinary departments from among the fields of letters, science,

law, agriculture, education, engineering, medicine, or business, each with

its own head, all to be placed under a director of the postgraduate school,

a position that might be filled by the president of the university

concurrently.

83

In actual fact, however, postgraduate training in Chinese

universities remained relatively undeveloped.

Chinese critics of the 1930s were aware of the shortcomings in the

country's higher education both in quantity and quality. Common

criticisms of college education were that it had not developed to meet the

needs of the nation, that there had been an imbalance in college

programmes with a' disproportionate' growth in such subjects

as

literature

80

K'o Shu-p'ing,' Wang Hsueh-t'ing hsien-sheng tsai chiao-chang jen-nei chih chiao-yu ts'o-shih'

(Educational measures taken

by

Wang Shih-chieh

as

minister

of

education), Cbuan-cbi wtn-bsucb

(Biographical literature), 259 (April 1982) 125.

81

Wang Ycn-chun and Sun Pin, eds.

Cbu

Cbia-bua bsien-sbmgyen-lun

cbi

(Dissertations

of Dr

Chu

Chia-hua), hereafter Cbu Cbia-bua, 139.

82

K'o Shu-p'ing, 126.

83

ttid.

125.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

39

2

THE

GROWTH

OF THE

ACADEMIC COMMUNITY

and

law

while science

and

technical subjects lagged behind,

and

that

funding

for

higher education

in

general was

far

from sufficient.

84

In

fact,

financing the colleges and universities from

a

variety

of

sources remained

difficult throughout the Nanking period.

In the

early 1920s

the

national

universities depended

on the

central government budget

for 90 per

cent

of their operating funds, with tuition and other fees and donations making

up less than

10 per

cent. While

the

central government budget

of

1934

stipulated that

15 per

cent

of

its annual expenditures should

be

assigned

to

the

support

of

education

and

cultural activities, that was

a

goal never

achieved

in

actuality;

in

1936,

for

example,

the

total amount budgeted

for education

and

culture stood

at a

high point

of

4-5

per

cent, while

military appropriations received 32-5 per cent and public debt service 24-1

per cent

in the

same year.

85

Compounding the problem for the national universities was the fact that

the central government, following the custom

of

earlier imperial regimes,

often assigned certain parts

of

a province's

tax

revenues

for the

support

of

a

national university located

in

that province; should

the

provincial

finances fall into disarray

for any

reason, payment

of

the allotted funds

to the university would become highly undependable.

86

Added to this was

the early lack

of a

uniform standard

on

which funding was

to be

based,

so that within

the

meagre total amount

of the

education budget

the

government's fairness might be called into question. Witness this petition

from the universities in Peking in 19 2 9:' Chung-shan University in Canton

and Central University

in

Nanking each

has a

student body

of 1,000 to

2,000,

and

each receives

a

monthly appropriation

of Ch.

$150,000

to

Ch. $160,000;

at

Peiping University there

are

seven colleges

and an

enrolment

of

3,500 students, yet the monthly appropriation

is

only some

Ch.

$90,000....'

8

?

Universities

and

colleges

at

the provincial level encountered still other

obstacles

in

getting public funding.

The

Nationalist government's effort

to centralize the national

finances

after

1929

was a long-drawn-out process.

In

the

collection

and

disbursement

of

tax monies, the procedures and

the

bureaucratic interrelationships

had to be

worked

out

between Nanking

84

Cbu Cbia-bm, 125, 138;

Ho

Ping-sung,'San-shih-wu-nien lai Chung-kuo chih ta-hsueh chiao-yii'

(Chinese higher education in the past

5 5

years),in Wan-Cb'itig, i3o;HuangChien-chung,'Shih-nien

ki

ti

Chung-kuo kao-teng chiao-yu' (Chinese higher education in the past ten years), in Kang-cban

cb'im sbib-nien

Mb

Chung-kuo (China

in

the decade before the war), 503.

85

Ch'en Neng-chih, 'Chan-ch'ien shih-nien Chung-kuo ta-hsueh chiao-yu ching-fei wen-t'i'

(Problems

of

financing higher education in China in the decade before the war),

U-sbib

bsueb-pao,

11 (June 1983) 173-6.

86

Ibid.

175-7. Examples

of

this condition

can

be

seen

in

the

cases

of

the National Chung-shan,

Wuhan, Chekiang, and Szechwan Universities from 1928

to

the early 1930s.

87

Ibid.

179.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

HIGHER EDUCATION AND NATION-BUILDING 393

and the provincial authorities. This led to the need for stop-gap funding

in several provinces, while local contingencies such as natural disasters

adversely affected provincial tax revenues.

88

Private institutions (including the Christian colleges and universities)

depended on a wide range of sources for support, running from central

government appropriations to private donations and tuition and other

fees,

the latter being most important. Those depending on government

support shared the problems that beset the public universities, while those

that relied primarily on private sources would be affected by economic

conditions in China and abroad.

89

Thus, financial insecurity constituted

a continuing challenge to the academic community.

Students, restless in the midst of endemic financial crises, and also

charged with ' being too interested in political issues', often vented their

frustration by staging riots and strikes, causing campus administrative

crises in turn.

90

This

'

interest in political issues' reflected the basic sense

of malaise in Chinese society as a whole, at a time when Japan's invasion

of Manchuria in 1931 was followed by the Shanghai undeclared war of

1932,

while KMT-CCP relations deteriorated into the long anti-CCP

military campaigns of the early 1930s. Fuelled by patriotic fervour, this

unrest was to find expression in the student movement of

1935

and 1936.

91

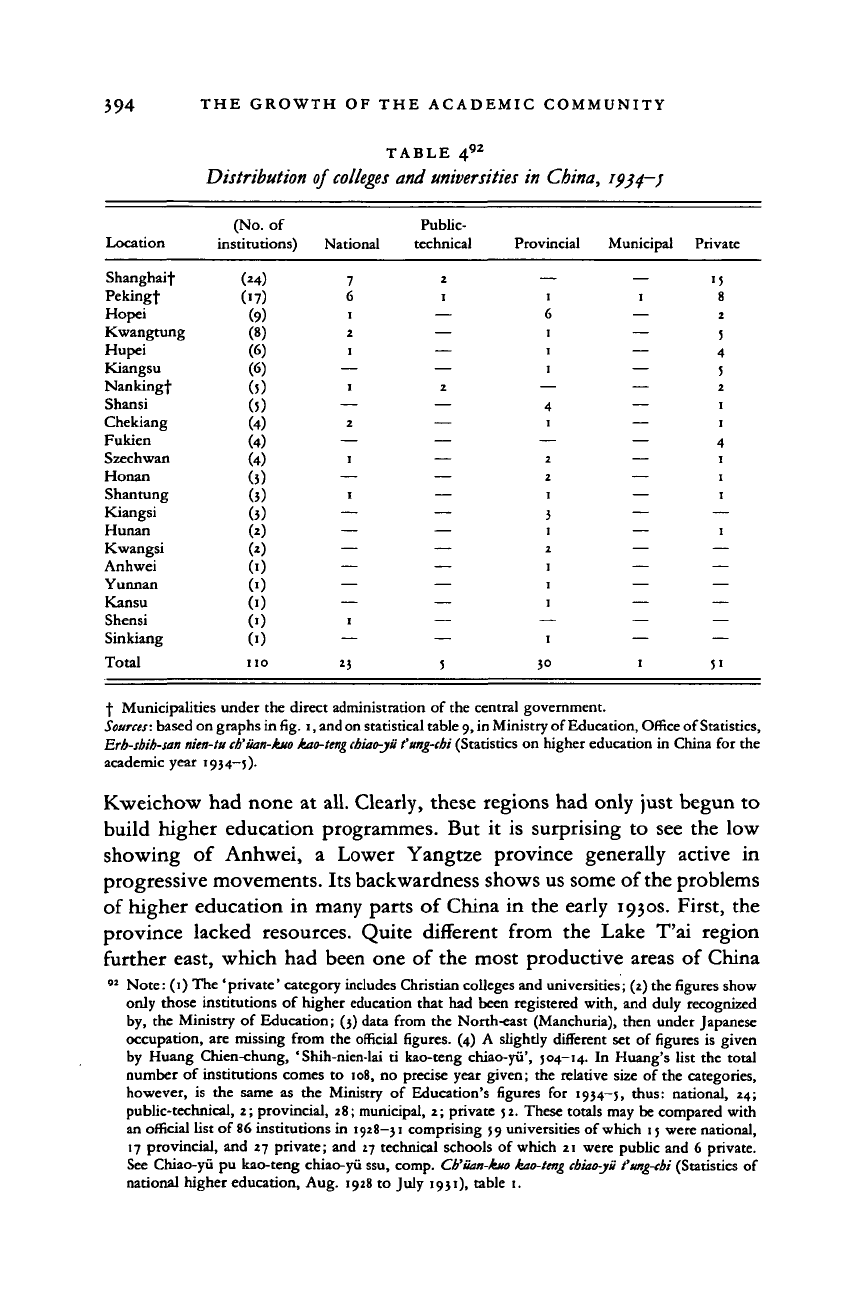

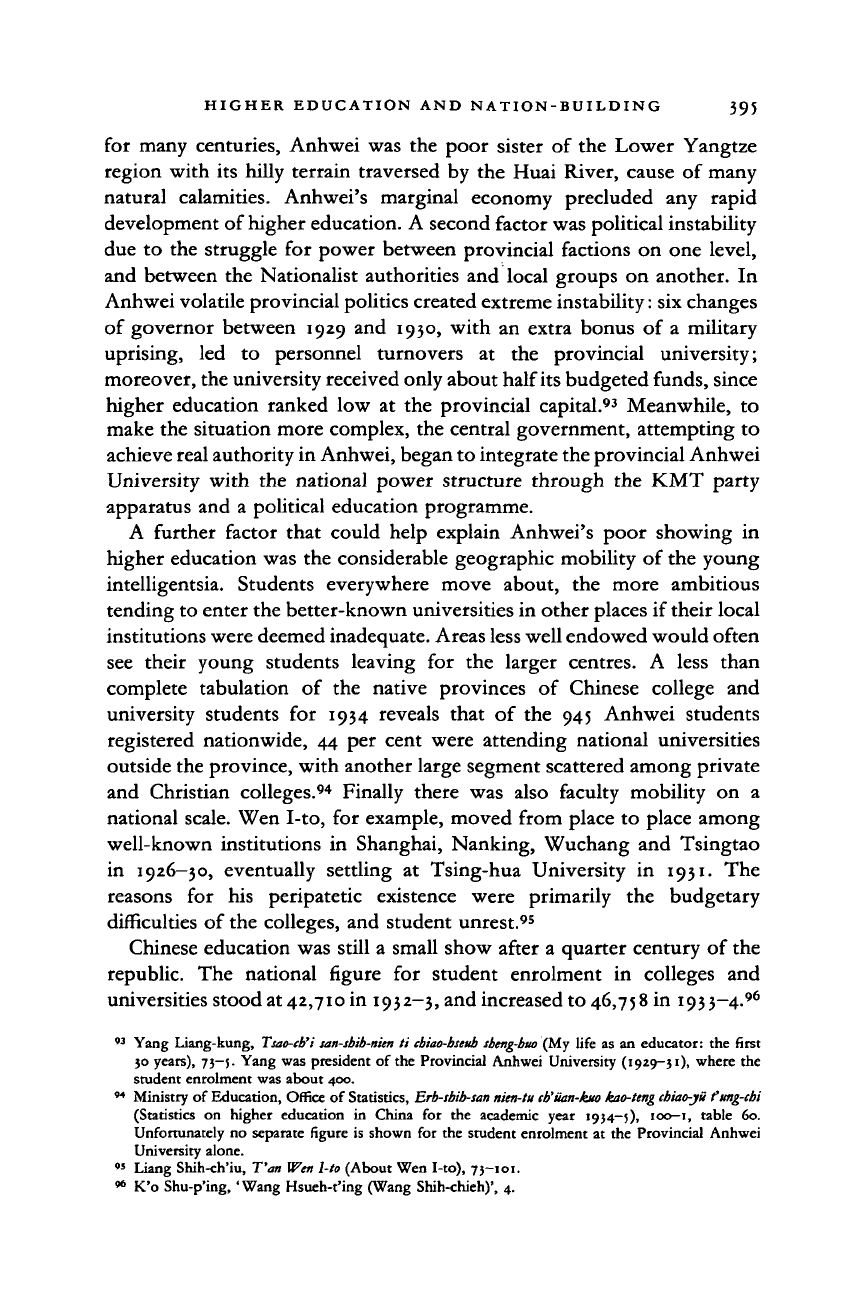

The distribution and types of institutions of higher education in 1934-5

(table 4) shows the extensive growth since 1922 (table 3), but also its

limitations. Most striking was the growth of the national government

sector after 1928 from 5 institutions to 23; second in the rate of growth

were provincial colleges, universities and technical institutions, along with

specialized private schools. Yet most of this expansion took place in just

a few locations, concentrated in eastern cities and coastal provinces: by

1934 Shanghai had 24 of the no institutions of higher education (or 21

per cent) in the entire country, while Peking followed with 17 (15-5 per

cent).

Among the provinces, Hopei had the largest number of provincial

institutions, leading that category with 9(8-2 per cent), and Kwangtung

was second with 8 (7-2 per cent). At the other end of the geographical

distribution were peripheral provinces like Sinkiang, Shensi, Kansu and

Yunnan that each had only one institution of higher education of any kind

in 1934, usually a provincial university or technical institute, while

88

Ibid.

185-90.

M

Ibid.

191-101.

°° As one example among many: on 27 June 1932 the students at National Tsing-tao University

struck against

final

examinations, which led to the resignation of

the

university's president, Yang

Chen-sheng; Ting Chih-p'in, Seventy years, 26}.

91

See Israel,

Student

nationalism,

ch. j; John Israel and Donald Klein,

Rebels and

bureaucrats:

China's

December

fers; on the social background see also Ka-che Yip, 'Nationalism and revolution: the

nature and causes of student activism in the 1920s', in Gilbert Chan and Thomas H. Etzold, eds.

China

m

the

if

20s,

94-70.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

394

THE GROWTH OF THE ACADEMIC COMMUNITY

TABLE 4

92

Distribution of

colleges

and

universities

in China,

1934—/

Location

(No.

of

institutions)

National

Public-

technical Provincial Municipal Private

Shanghaif

Pekingf

Hopei

Kwangtung

Hupei

Kiangsu

Nankingf

Shansi

Chekiang

Fukien

Szechwan

Honan

Shantung

Kiangsi

Hunan

Kwangsi

Anhwei

Yunnan

Kansu

Shensi

Sinkiang

(M)

(17)

(9)

(8)

(6)

(6)

(5)

(5)

(4)

(4)

(4)

(3)

(3)

(3)

M

00

(0

(>)

(0

(0

(0

7

6

1

2

1

1

2

1

1

1

15

8

2

5

4

5

2

Total

3°

f Municipalities under the direct administration

of

the central government.

Sources:

based on graphs in

fig.

i,

and on

statistical table 9,

in

Ministry of Education, Office of Statistics,

Erb-sbib-san nien-tu

ch'uan-kuo

kao-teng

chiao-yu

fung-cbi (Statistics

on

higher education

in

China

for the

academic year 1934—5).

Kweichow had none

at

all. Clearly, these regions had only just begun

to

build higher education programmes.

But it is

surprising

to see the low

showing

of

Anhwei,

a

Lower Yangtze province generally active

in

progressive movements. Its backwardness shows us some of the problems

of higher education

in

many parts

of

China

in

the early 1930s. First,

the

province lacked resources. Quite different from

the

Lake

T'ai

region

further east, which

had

been one

of

the most productive areas

of

China

n

Note: (1) The 'private' category includes Christian colleges and universities; (2) the

figures

show

only those institutions

of

higher education that had been registered with, and duly recognized

by, the Ministry

of

Education

5(3)

data from the North-east (Manchuria), then under Japanese

occupation, are missing from the official figures.

(4) A

slightly different

set of

figures

is

given

by Huang Chien-chung, 'Shih-nien-lai

ti

kao-teng chiao-yu', 504-14.

In

Huang's list the total

number

of

institutions comes

to

108,

no

precise year given; the relative size

of

the categories,

however,

is the

same

as the

Ministry

of

Education's figures

for

1934—5, thus: national,

24;

public-technical, 2; provincial, 28; municipal, 2; private 52. These totals may be compared with

an official list

of

86 institutions in 1928—31 comprising 59 universities

of

which 15 were national,

17 provincial, and

27

private; and 27 technical schools

of

which 21 were public and

6

private.

See Chiao-yu

pu

kao-teng chiao-yu ssu, comp.

Ch'uan-kuo kao-teng cbiao-yu

t'ung-cbi

(Statistics

of

national higher education, Aug. 1928

to

July 1931), table

1.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

HIGHER EDUCATION AND NATION-BUILDING 395

for many centuries, Anhwei was the poor sister

of

the Lower Yangtze

region with its hilly terrain traversed by the Huai River, cause of many

natural calamities. Anhwei's marginal economy precluded

any

rapid

development of higher education. A second factor was political instability

due

to

the struggle for power between provincial factions on one level,

and between the Nationalist authorities and local groups on another.

In

Anhwei volatile provincial politics created extreme instability: six changes

of governor between 1929 and 1930, with an extra bonus

of

a military

uprising,

led to

personnel turnovers

at the

provincial university;

moreover, the university received only about half its budgeted funds, since

higher education ranked low

at

the provincial capital.

93

Meanwhile,

to

make the situation more complex, the central government, attempting to

achieve real authority in Anhwei, began to integrate the provincial Anhwei

University with the national power structure through the KMT party

apparatus and a political education programme.

A further factor that could help explain Anhwei's poor showing

in

higher education was the considerable geographic mobility of the young

intelligentsia. Students everywhere move about,

the

more ambitious

tending to enter the better-known universities in other places if their local

institutions were deemed inadequate. Areas less well endowed would often

see their young students leaving

for the

larger centres.

A

less than

complete tabulation

of the

native provinces

of

Chinese college

and

university students

for

1934 reveals that

of

the 945 Anhwei students

registered nationwide, 44 per cent were attending national universities

outside the province, with another large segment scattered among private

and Christian colleges.

94

Finally there was also faculty mobility

on a

national scale. Wen I-to, for example, moved from place to place among

well-known institutions

in

Shanghai, Nanking, Wuchang and Tsingtao

in 1926-30, eventually settling

at

Tsing-hua University

in

1931.

The

reasons

for his

peripatetic existence were primarily

the

budgetary

difficulties of the colleges, and student unrest.

95

Chinese education was still a small show after a quarter century of the

republic.

The

national figure

for

student enrolment

in

colleges

and

universities stood at 42,710 in

1932-3,

and increased to

46,75 8

in

193

3~4.

96

93

Yang Liang-kung,

Ttao-cb'i san-sbih-nkn

ti

cbiao-bstub sbeng-buo

(My life as an educator: the first

50 years),

73—5.

Yang was president of the Provincial Anhwei University (1929-31), where the

student enrolment was about 400.

54

Ministry of Education, Office of Statistics,

Erb-ibib-san nicn-tu cb'uan-kuo kao-teng cbiao-jii fung-ebi

(Statistics

on

higher education

in

China

for the

academic year 1934—5),

100—1,

table

60.

Unfortunately no separate figure is shown for the student enrolment

at

the Provincial Anhwei

University alone.

« Liang Shih-ch'iu,

Tan

Wen l-to (About Wen I-to),

73-101.

06

K'o Shu-p'ing, 'Wang Hsueh-t'ing (Wang Shih-chieh)',

4.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

396 THE GROWTH OF THE ACADEMIC COMMUNITY

College graduates totalled 7,311 in 1933 and 7,5

52

in 1934, hardly enough

to keep pace with the growth of government. These results were too small

when projected against the size of

the

country. In a comparative summary

of higher education in twenty-six countries compiled by the Ministry of

Education in 1935, China ranked last, showing o-88 college-level student

for every 10,000 population in 1934. Turkey, ranked 25 just above China,

had in 1928 (five years into the regime of Ataturk) three college students

per 10,000 population.

97

In short, college-educated persons at this high

point of Republican China still constituted a thin top segment of the

modern elite, hardly more numerous than the upper degree holders of the

scholar-gentry class had been in the traditional era. Meantime the detailed

substance of modern higher education, the content of the curriculum and

how well it was taught, remain still obscure. The institutional record

comes almost entirely from professors and administrators rather than from

students. We have as yet little idea of the instruction that was actually

made available, its appropriateness to meet China's current needs, or even

the numbers it reached.

Advanced

research

With the advent of the Nationalist government the scholarly community

was encouraged in its hopes by the creation of

a

central research academy,

the Academia Sinica. Plans for the founding of a national research institute

had been discussed in 1927, initially by Ts'ai Yuan-p'ei, Chang Jen-chieh

(Chang Ching-chiang), and Li Shih-tseng, all veteran KMT members with

years of service in modern education. Their common goal was to create

in China the type of government-financed research at advanced levels that

had so strongly impressed Ts'ai years before in Germany. Later on

younger scientists and scholars, including Hu Kuang-fu, Wang Chin,

Wang Shih-chieh, and Chou Lan (Chou Keng-sheng), were asked to join

in the planning. Academia Sinica's formal founding was announced in

Shanghai on

9

June

1928,

with Ts'ai Yuan-p'ei

as

its government-appointed

president.

98

Placed directly under the supervision of the central government,

the academy was to have three divisions: Research, comprising the

individual research institutes; Administration, headed by a secretary-

general

;

and an advisory organ called the National Science Council that

97

Ministry of Education, Statistics ipjf-j, section 2, 'Tables', 2-3, table 1, 'Higher education in

China and major nations in the world'. The years included in the table range from 1928 to 1934;

in contrast to China and Turkey, the US (1932) ranked first with 73 college students per 10,000

population, but Japan ranked twenty-second with 9 per 10,000.

98

Tao Ying-hui, 'Ts'ai Yuan-p'ei yii Chung-yang yen-chiu-yuan 1927-1940* (Ts'ai Yuan-p'ei and

the Academia Sinica, 1927—1940), in Bulletin of

the

Institute of Modem History, 7 (1978) 6.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

HIGHER EDUCATION AND NATION-BUILDING 397

consisted

of

both charter members and members by special invitation."

Inspired by

a

vision

of

China clothed

in

modernity and contributing

to

the fund

of

world knowledge,

the

scholars

and

scientists began their

research projects as soon as the institutes were organized. Two features

stood out:

the

majority

of

the research institutes were

in the

natural

sciences, and

a

substantial portion of the leaders of Academia Sinica had

been active in the work of the Science Society as well as in the emerging

professional associations.

100

Academia Sinica, however, had no monopoly on the top scientists and

scholars. As differences of view widened between Ts'ai Yuan-p'ei and Li

Shih-tseng (Li Yii-ying, who had received advanced training

in

France)

over the proper structure

of

higher education and research,

Li

left

the

original Academia Sinica group, and in 1929 founded the National Peiping

Research Academy, a separate entity under which for the next two decades

half

a

dozen scientific institutes carried

out

advanced research

and

publication. Li Shu-hua later joined this institute as its deputy director.

I01

In both science and social science, one important new development was

the young returned-scholars' insistence that field investigation be given

equal attention with laboratory analysis and library research.

But

field

research, using the methods

of

modern science, had

to

demonstrate

its

value

to

Chinese classical scholars trained

to

literary research only. This

demonstration began when Chinese palaeographers versed in the ancient

writing

on

prehistoric bronzes became aware

in the

1890s that 'oracle

bones'

from

the

Anyang area bore inscriptions

in

prehistoric Chinese.

Collecting thousands of inscribed oracle bones from dealers, these scholars

began to deciper the prehistoric characters and were prepared

to

dig

for

more. Another stimulus for field work came from the Geological Survey

of China set up

in

1916 under the Ministry

of

Industry and Commerce,

to map the country and survey its natural resources. Under the energetic

leadership

of

Ting Wen-chiang (V. K. Ting), Weng Wen-hao,

Li

Ssu-

kuang (J. S. Lee)

and

others, mainly trained

in

Britain,

the

survey's

mapping and explorations set new standards.

It

also sponsored work

in

palaeontology that culminated

in

the discovery

of

Peking Man. Set

up

in the Peking Union Medical College was

a

Cainozoic Laboratory which

in

the

1920s demonstrated

how

explorers

and

scientists from

New

York State (A. W. Grabau, palaeontological adviser

to the

Geological

Survey), Canada (Davidson Black), Sweden (J. G. Andersson), Germany

99

Ibid.

6-7. The National Science Council, when fully set up in 1935, had eleven charter members

that consisted

of

the president

of

the Academia Sinica and

the

directors

of

the

ten

research

institutes under him; see

ibid.

9-11.

100

Ibid.

33-6; e.g. Yang Ch'uan, Ting Wen-chiang, Jen Hung-chiin, Wang Chin, Chou Jen, Chu

K'o-chcn, and Wang Chia-chi were all staunch members of the Science Society.

""

Ibid.

17.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

398 THE GROWTH OF THE ACADEMIC COMMUNITY

(J.

F.

Weidenreich),

and

France (P. Teilhard

de

Chardin) could help train

a

new

generation

of

Chinese archaeologists including

P'ei

Wen-chung,

who

led the

excavations that

in

1929

discovered Peking

Man

at

Chou-

k'ou-tien, south-west

of

Peking.

I02

The most famous discovery after Peking Man was

the

unearthing of the

formerly-only-legendary Shang dynasty capital

at

Anyang, Honan.

In 1928

the Academia Sinica's Institute

of

History

and

Philology under

the

direction of Fu Ssu-nien, who

had

been

a

student leader

of

the

May Fourth

movement

at

Peita, added archaeology

to

its historical

and

linguistic work.

Fu invited

Li

Chi, who had

taken

his Ph.D.

in

1923

in

anthropology

at

Harvard,

to

direct

the

Anyang project.

The

excavations pursued there

from

1928

to

1937

have been described

in Li's

remarkable book, Anyang.

It recounts

an

heroic saga,

how the

field work, laboratory analyses

and

scientific study

of the

results were carried

to

completion over decades

of

warfare

and

dislocations

-

a

great achievement

of

scholarship.

103

In medical education

the

highest standards were

set by the

Peking

Union Medical College which, following

a

century

of

medical efforts

by

missionaries,

was

supported from

1915 to

1947

by the

Rockefeller

Foundation

to be a

research

and

training hospital.

Its

300

or

more

graduates after

1924

helped staff

the

national public health service while

its faculty's researches contributed especially

in

parasitology

and in

dealing with communicable diseases like schistosomiasis, hookworm

and

kala-azar.

104

Universities also helped

to

extend

the

frontiers

of

learning.

The

first

had been

the

Institute

of

Chinese Studies founded

by

Peita

in

1921 under

the directorship

of

Shen Yin-mo. Although

its

plans

at

Peita included

publication

of

research results

and a

drive

to

recruit corresponding

research fellows, this institute

as

it

came into being was actually more like

a Western postgraduate school, withyen-chiu-sheng (postgraduate students

or ' research students') working independently with individual professors

in pursuit

of

given topics.

I0S

Admission

to

the

institute

was

determined

at first

not by

the

possession

of a

college degree

but

by

submission

of

previous professional publications.

102

Jen Hung-chiin,' Wu-shih-nien lai

ti

k'o-hsueh' (Science

in

the past 5 o years),

in

P'an Kung-chan,

ed. Wu-shih-nien

lai

ti

Cbung-kuo (China in the past 50 years), hereafter cited as Jen,' Wu-shih-nien',

190;

BDRC 3.67;

and

Li

Chi, Anyang, 34—48.

103

Li

Chi,

Anyang; Kwang-chih Chang,

The

archaeology

of

ancient China,

3rd

edn., 1977,

3-18

summarizes

the

growth

of

archaeological research

on

China.

104

See

Mary Brown Bullock,

An

American transplant; Mary

E.

Ferguson, China Medical Board and

Peking Union Medical College;

and

John

Z.

Bowers, Western medicine

in

a

Chinese palace.

The

files

in

the

Rockefeller Foundation archives indicate that

in

addition

to its

broad medical concerns,

the foundation assisted work

in

mass education, agricultural research, librarianship

and

other

areas,

especially

in

the

1930s.

105

Tao Ying-hui,

'

Ts'ai/Peita', 397.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

HIGHER EDUCATION AND NATION-BUILDING 399

Ideals, enthusiasm, and expert planning aside, the work of

the

academic

community in the 1920s still encountered a frequent obstacle, inadequate

financial support. More than one contemporary record refers to this in

a matter-of-fact tone: ' China being in the midst of civil war, government

colleges and universities suffered from arrears in receipt of budgeted

revenues...

>I06

In order to make ends meet some professors had to teach

at two or more institutions simultaneously. In such circumstances, getting

allocations for research would be difficult, and so assistance from friends

and from outside sources could be crucial.

The sociology of knowledge may be expected to benefit from detailed

studies of the personnel configurations, groups, factions and cliques that

advanced modern learning in Republican China. To begin with, the small

elite of students abroad followed tradition by forming student fraternities

or associations

{hui)

for mutual support among themselves. Quite different

in aim and style from the secret society lodge

{tongs)

among Chinatown

merchants, these student fraternities selected and counselled junior

members, convened summer retreats, and formed personal bonds of trust

and friendship that could be of

use

later on in China. Best known of these

several groups was CCH (abbreviated from Ch'eng-chih hui, an

'association for the achievement of one's life goals', also known as 'Cross

and Sword').

107

On their return to China the young Ph.D.s became professors committed,

like all professors, to reproducing themselves; a fortunate few in

university institutes for advanced research were able to pursue their

specialities, while younger students who assisted them received training.

Peita, Tsing-hua, and Yenching in the Peking area, and Chung-shan

University and Lingnan in Canton, for example, set up specialized

research institutes and the results, generally of high quality, were

published in their own academic journals.

Among the outstanding institutes of this type was the Nankai Institute

of Economics, established in 1931 under the leadership of Franklin Ho

(Ho Lien), who as professor of public finance and statistics at Nankai

University was also pioneering Nankai's systematic studies of North China

industries. This charted a new direction in the teaching of economics in

China; instead of using Western experience and examples, the study of

Chinese economic life was not based on data gathered from within the

106

H. D.

Fong, Reminiscences of a Chinese economist

at

70, 31.

107

Now

no

longer secret, CCH published

a

history and directory.

Its

membership included

Chi

Ch'ao-ting, Chiang T'ing-fu (T.

F.

Tsiang), Chiang Meng-lin (Monlin), Fang Hsien-t'ing

(H.

D.

Fong),

Ho

Lien (Franklin Ho), K'ung Hsiang-hsi (H.

H.

Kung), Kuo Ping-wen, Meng

Chih (Paul Mcng), Tsou Ping-wen, Weng Wan-ko (Wango Weng), Yen Yang-ch'u (Y. C. James

Yen).

Personal communication from Wango Weng, August 1979.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

4°O THE GROWTH OF THE ACADEMIC COMMUNITY

country. Ho used personal contacts he had made as a graduate student

in the United States, including membership in CCH (of which Chang

Po-ling was also a member), and was able to attract other young and

well-trained economists. H. D. Fong (Fang Hsien-t'ing), for example, a

Yale Ph.D. of 1928, joined the Nankai faculty in 1929, and became a

member of the Committee on Social and Economic Research that evolved

into the Institute of Economics.

108

Ho and Fong were soon joined by Wu

Ta-yeh, Li Cho-min (Choh-min Li), Lin T'ung-chi, and Leonard G. Ting,

all of whom became well-known economic researchers.

While Nankai as a private university had the advantage of financial in-

dependence and administrative stability, still its resources were inadequate

for the ambitious design of the institute, which Ho modelled on the

London School of Economics. To bring the institute into being, Ho had

contributed a personal gift of

Ch.

$500 as well as his own library, and in

1929 a grant of

Ch.

$2,000 from the Institute of Pacific Relations assured

the institute of its existence. This also marked the beginning of

the

Nankai

Institute Library that later became famous for its comprehensive collection

on the Chinese economy.

109

At this juncture Professor R. H. Tawney of

London arrived at Nankai University for research and to give lectures

during the winter of 1929-30.

110

The international visibility thus gained,

and evidence of the high level of scholarship among the Chinese

economists, led to a five-year grant in 1932 from the Rockefeller

Foundation. Thus aided, the institute published some twenty well-

researched monographs (including massive field data) before war erupted

in 1937 and the Nankai campus was devastated.

111

Research on land use as pioneered at Cornell was undertaken at

Nanking University in the 1920s by J. L. Buck and others, whose sample

data on the Chinese farm economy opened up the whole field of agronomic

technology. From 1934 this was pursued by Shen Tsung-han and others

at the Chinese National Agricultural Research Bureau.

112

Sociology as it developed at Yenching University began with social

108

Fong, Reminiscences,

36,

39-40. Fong points

to the

many able faculty members Chang Po-ling

was recruiting

for

Nankai, 'especially from among members

of

his

own

fraternity Chen

[sic]

Chih

Hui'.

Ibid. 38.

109

Ibid. 41, 42, 4j.

110

Ibid.

45. Tawney's research resulted in the book hand and

labour

in China (1932). He also

contributed to a League of Nations report along with C. H. Becker (Berlin), M. Falski (Poland),

and P. Langevin (Paris),

The

reorganisation

of

education

in

China,

which questioned many things

including the appropriateness for China of the American educational model.

111

Fong,

Reminiscences,

45-7. The grant enabled the Nankai Institute to add half a dozen faculty

members

recently

returned

from the US, including Wu Ta-yeh, Li Choh-min, Lin T'ung-chi and

Leonard G. Ting.

112

Sec John Lossing Buck,

Land utilisation

in

China;

also T. H. Shen,

Sben Tsung-han

t^u-sbu

(Shen

Tsung-han's memoirs), by a Cornell-trained leader in the field.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008