The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13: Republican China 1912-1949, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER 8

THE GROWTH OF THE

ACADEMIC COMMUNITY 1912-1949

Institutions

of

learning

not

only educate oncoming generations

but

also

create, import

and

disseminate culture

and

technology.

By

performing

such vital functions, a modern nation's schools and colleges, libraries and

laboratories become

of

central importance

to the

state

as

well

as to the

society in general. In the Chinese

case,

moreover, education had from early

times been

a

principal concern

of

government, and

so it

would become,

eventually,

a

central focus

of the

Chinese revolution after

1949.

Meanwhile during

the

first half

of the

twentieth century, education

proliferated

in

China

in the

most varied forms and with many kinds

of

foreign influence

and

participation.

The

voluminous record

is

widely

scattered

and

just beginning

to be

studied.

1

For

example,

new

work

suggests that functional literacy among

the

common people was more

widespread than

was

formerly assumed. Many important aspects

of

twentieth-century education need attention

-

the inheritance

of

social

style and pedagogic method from

the

thousands

of

academies

(shu-juari)

that had functioned in late imperial China, the growth of

a

modern school

system

and of

urban public education through

the

press,

the

formal

education

of

women,

the

rise

of

publishing houses like

the

Commercial

Press (Shang-wu yin-shu-kuan, founded

at

Shanghai

in

1896,

a

great

publisher of journals as well as textbooks), and the founding of educational

associations

and new

schools

as

seedbeds

of

reform

and

revolution.

2

1

For helpful comments

on

this chapter

we

are indebted

to

Chiang Yung-chen, Paul A. Cohen,

Merle Goldman, Jerome Grieder, William

J.

Haas, John Israel

and

Suzanne Pepper, among

others. Education is a subject peculiarly rich in documentation. The principal early compilations

of documents

by

Shu Hsin-ch'eng

(4

vols. 1928;

3

vols. 1962) and

the

most recent

by

Taga

Akigoro

(;

vols. 1976) are noted in the bibliographical essay below.

1

On literacy see Evelyn S. Rawski,

Education

and

popular literacy

in

Cb'ing

China.

On

sbu-juan

see

Tilemann Grimm, 'Academies and urban systems

in

Kwangtung',

in G.

William Skinner,

ed.

Tie

city in late

imperial

China,

47 5

-98.

On the new school system to

1911,

Sally Borthwick,

Education

and social change

in

China:

the

beginnings

of

the modern

era.

On the

Commercial Press's work

in

education see Wang Yun-wu, Shang-wujin-sbu-kuan ju

bsin cbiao-ju nien-p'u

(A chronology

of

the

Commercial Press

and the New

Education), covering events, publications, reports,

etc.

1897—1972.

On the

vicissitudes

of

education

in

one province (Shantung)

see

David D. Buck,

'Educational modernization in Tsinan, 1899-1937', in Mark Elvin and G. William Skinner, eds.

The Chinese city between two

worlds,

171-212. The overall problems

of

education

in

modern China

will be discussed by Suzanne Pepper in CHOC 14, ch.

4.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

3^2 THE GROWTH OF THE ACADEMIC COMMUNITY

Within this broad terrain,

the

focus

of

this chapter

is

limited

to

higher

education. This fact

in

itself testifies

to

the

scholarly neglect thus

far of

the vital story of elementary and secondary education in Republican China.

It also reflects the greater visibility of efforts made by China's revolutionary

educators to create elite institutions capable of producing new upper- class

leaders.

After 1911

the

Chinese government's prolonged weakness opened

an

unusual window

of

opportunity

for

China's revolutionary educators.

Fervently patriotic

and

still endowed

as a

class with

the

prestige

of

scholarship, they

had

an

opportunity

to

lead

the way

in

creating

the

academic institutions needed

for

modernity. Their

new

role

had

both

intellectual

and

institutional aspects. Intellectually they confronted

the

necessity

of

reconciling

the

Chinese

and

Western Cultural traditions

-

a

task more awesome

in

its dimensions than most human minds have ever

faced.

The

vast proportions

of

this intellectual problem

and

how

it

was

approached have been appraised

in

other volumes

in

this series.

3

The

present chapter therefore focuses

on

the

academic community

and

its

institutional achievements

in the

first half

of

the twentieth century.

We confront here a tremendously complex but largely unexplored story

with three main facets. First, China's intellectual history has outpaced her

institutional history,

and we

know more about

the

late Ch'ing schools

of Neo-Confucian thought

—

the Sung

and Han

learning,

New

Text

and

Old Text scholarship, even

the

T'ung-ch'eng school

-

than we

do

about

the network

of

academies, libraries, printing shops

and

patrons that

sustained Confucian scholarship. Second,

in

China's relations with Japan,

politics

has

thus

far

eclipsed

the

academic story. Most

of

the thousands

of Chinese students who went

to

Tokyo returned

to

careers

of

service

in their homeland;

not all by any

means became revolutionaries. Many

no doubt taught

in

the new

schools

of

law and

government

{fa-cheng

hsueh-t'an£)

that proliferated

in the

late Ch'ing,

but the

content and reach

of their teaching, like other aspects

of

Japanese influence

in

Republican

China, remain still largely unknown. Third,

the

educational influences

streaming into China from Europe

and

America constitute

a

vast terrain

of unimaginable variety

and

unexplored proportions. Nearly

all the

nations

and all the

disciplines were involved

in

this largest

of

all cultural

migrations.

For

example, Catholic

and

Protestant missions

in all

their

diversity

lay

behind

the

Christian colleges

in

the

Chinese Republic,

yet

they were

but

threads

in

a

tapestry.

The

modern West was

in

flux

and

China herself was embarked on many transformations. Methods, curricula,

textbooks

and

systems

of

instructions from Japan, Europe

and

America

3

See

CHOC 11,

ch. 5 and

CHOC 12,

chs. 7 and 8.

For

a

more recent fresh account

see

Jerome

B.

Grieder, Intellectuals and

tie

state

in

modern China:

a

narrative history.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EMERGENCE OF MODERN INSTITUTIONS }6)

all added their stimuli

to

the educational maelstrom

in

which the deeply

imbedded values and social roles

of

the

old

Chinese literati underwent

a gradual adaptation

to

modern needs. Given this preponderance

of

the

yet-to-be-discovered over the known, this chapter attempts only to block

out major areas and aspects of a new field.

One feature, however,

is

clear

-

in the face

of

Japanese expansion the

institutional structure of the unequal treaty system including extraterritori-

ality persisted;

and

foreign, especially American, influence

on

Chinese

higher education reached

a

high point despite the rapid rise

of

Chinese

nationalism.

The

1920s

in

particular were

a

period

of

vigorous Sino-

American collaboration

in

science and higher education.

THE EMERGENCE

OF

MODERN INSTITUTIONS 1898-1928

For analytic purposes we look

in

succession

at

the training of personnel,

the formation

of

certain major institutions, and aspects

of

research and

financial support.

In

each case

our

reconnaissance tries

to

offer

representative examples drawn from

a

terrain which

is

still imperfectly

surveyed. Provincial, municipal and technical/vocational institutions are

largely beyond our purview.

4

Personnel:

an

elite trained abroad

The leaders in the building-up of higher education were

a

truly extraordinary

group

of

people who responded

to

the needs

of

an extraordinary time.

When China's modern transformation required the creation

of

a system

of higher education comparable

to the new

systems arising

in

other

countries, this meant

in

human terms the training

of

a new scholar class

versed

in

Western

as

well

as

Chinese learning

—

a truly revolutionary

departure from long-established tradition. So revolutionary was this very

idea

-

that Chinese could and indeed must learn from foreigners

-

that

efforts

in

this direction after i860

had

been comparatively

few and

ineffective in comparison, for example, with Japan and India. The Ch'ing

government's inability

to

provide modern learning within China and

to

control those Chinese students it sent to study in Tokyo had in fact proved

to be

a

major cause of its downfall. The new educational elite thus grew

to maturity

in an age of

revolutionary change.

In

setting

up new

institutions they felt themselves

to be

creators

of a

new world,

not by

any means the defenders

of

an establishment already

in

being. One can

4

In

1922

a

survey by the National Association for the Advancement

of

Education reported the

existence

of

1,553 vocational schools in China. By 1925 the National Association for Vocational

Education was composed

of

more than ioo educational bodies. China jear

book,

hereafter CYB,

1926,

423.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

564 THE GROWTH OF THE ACADEMIC COMMUNITY

only imagine the adventurous and determined spirit of those Chinese

women who came into higher education at a time when footbinding was

still being widely practised as the ancient Chinese way of keeping women

in subjection.

Several things characterized these educators. First of all, they were

generally men and women educated abroad. The generation of Liang

Ch'i-ch'ao (1873-1929) had sought foreign learning in Japan, that of Hu

Shin (1891—1962) sought it in Western Europe and the United States. The

size of this student migration is imperfectly known because, for example,

many more Chinese enrolled in Japanese schools and colleges than ever

graduated. One estimate of enrollees during 1900-37 is 136,000, while the

best figure for Chinese graduates from Japanese institutions during

1901-39 is i2,ooo.

s

The political contribution made by these returned

students from Japan stands out in the annals of the Revolution of 1911;

their academic contribution has been generally lost to sight. After 1915

the growing antagonism engendered by Japanese expansion and China's

rising nationalism all but eclipsed the Chinese academic debt to Japan;

no doubt future studies will exhume and appraise it.

6

The Sino-Japanese antagonism helped to turn Republican China's

scholars toward Western Europe and America. Chinese students making

the longer journey to the West required more financing and so were

more carefully chosen, more specifically committed, and more likely to

complete their studies. One estimate is that during the century

1854-195

3,

21,000 Chinese studied in American institutions.

7

However these figures may be further refined and analysed, it is evident

that the 20,000 or so Chinese who returned from the West in the twentieth

century were a remarkably small but potent group. In numbers, among

a population of some 400 million, they were as few in proportion as had

been the metropolitan graduates

(chin-sbih)

under the old regime. But

where their predecessors in the triennial examinations at Peking had

customarily accepted a personal bond of loyalty to the emperor who

nominally conducted the palace examinations, these scholars from the

Chinese Republic found that their foreign experience confirmed their

patriotic devotion to the Chinese nation. This new' returned-student' elite

were more than ever mindful of the Sung reformer Fan Chung-yen's

5

See M. Jansen, CHOC 11.351, citing Saneto Keishu, Cbugohgin Nibon ryugaku sbi, the major work

of the top Japanese specialist on Sino-Japanese educational relations.

6

The principal survey by Y. C. Wang, Chinese

intellectuals

and the West 1872-1)4), actually includes

the late Ch'ing efforts to learn from Japan as well as extensive data on many later aspects of

this subject. Aspects of Sino-Japanese intellectual relations are explored in Akira Iriye, ed. The

Chinese and the Japanese: essays in political and cultural interactions.

7

How many graduated is uncertain. See Y. C Wang, 119-20, 167, 185, citing data from the China

Institute in America.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EMERGENCE OF MODERN INSTITUTIONS }6j

dictum,'

a

scholar should be the first to become concerned with the world's

troubles and the last

to

rejoice

at

its happiness'.

8

While the proportions

of returned students who went into government, industry, the professions,

the arts and education

is

still unknown,

it

seems plain that they enjoyed

a special status derived from

old

custom

as

well

as

from modern

revolution. They functioned

in a

widespread network

of

interpersonal

relations

or

kuan-hsi.

Those who elected

to

embark upon

the

task

of

creating a system of higher education clung firmly to the classical tradition

that

the

scholar

is not a

mere technical expert

but

must think like

a

statesman

on

behalf

of

the whole society, rulers and people alike. This

sense

of a

responsibility helped

the

new leaders returned from Europe

and America

to

begin building

the

academic institutions

of

the early

republic

—

the colleges, universities, libraries, laboratories

and

research

institutions needed

in a

twentieth-century nation.

Yet their extraordinary status

as a

selected

(or

self-elected)

few

who

had achieved the top level

of

scholarship was not

an

unmixed blessing.

Their experience abroad, usually

a

period

of

several years necessary

to

secure

a

Ph.D. degree, led these liberal intellectuals into

a

cosmopolitan

stance

of

unavoidable ambivalence.

9

Like

all who

study abroad, they

became

to

some degree bicultural,

at

home both

in

China's elite culture

and in that of the outer world. Added to their elite status as scholars, this

acquisition of foreign ways made them all the more alienated from village

China. The fact that they forged common bonds with the Western liberal

arts tradition ensured that the New Culture movement in education would

foster more than

the

mere transfer

of

technology,

but it

raised acutely

the problems

of

making their foreign training effective and relevant

to

China's problems, both

in

fact

and

(equally important)

in the

eyes

of

China's political

and

military elite

who

were called upon

to

give

the

educators continuing support.

At the

same time, some feel that their

foreign orientation threatened these scholars with deracination,

a

loss

of

the sense

of

community with their homeland,

in

short, anomie

and

alienation. Bicultural experience can confuse one's identity. The propor-

tions of this problem are as yet unknown.

It

may have been all the greater

for those many individuals

of

the May Fourth generation who had,

in

fact,

a

threefold educational background: Chinese (traditional and early

modern), Japanese, and American-European.

10

Thus the task

of

importing foreign learning

(in

both technology and

8

See James T.

C

Liu, 'An early Sung reformer: Fan Chung-yen', in John

K.

Fairbank, ed. Chinese

thought

and institutions, 111.

9

The paradoxes

of

this ambivalence were explained

in

particular

by

Joseph Levenson.

His

last

work was Revolution and cosmopolitanism: the Western stage and the

Chinese

stages.

10

To get an impression of the type of training received by educators of the Republican revolutionary

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

366 THE GROWTH OF THE ACADEMIC COMMUNITY

values)

was

complicated both inside

and out.

Within

himself,

the

foreign-trained educator had

to

work

out his

self-image

of

how best

to

make his contribution. In his environment, meanwhile, he might confront

quite different expectations

of

how

he

should behave. One new feature

of modern education was the burden

of

administration. Residential and,

soon, coeducational colleges were

a new

phenomenon with

an

infinite

capacity

to

generate student opinion and organization, leading

to

strikes

and political movements. The new students

of

the Republic shared their

teachers' concern

and

sense

of

responsibility

for the

fate

of

the nation.

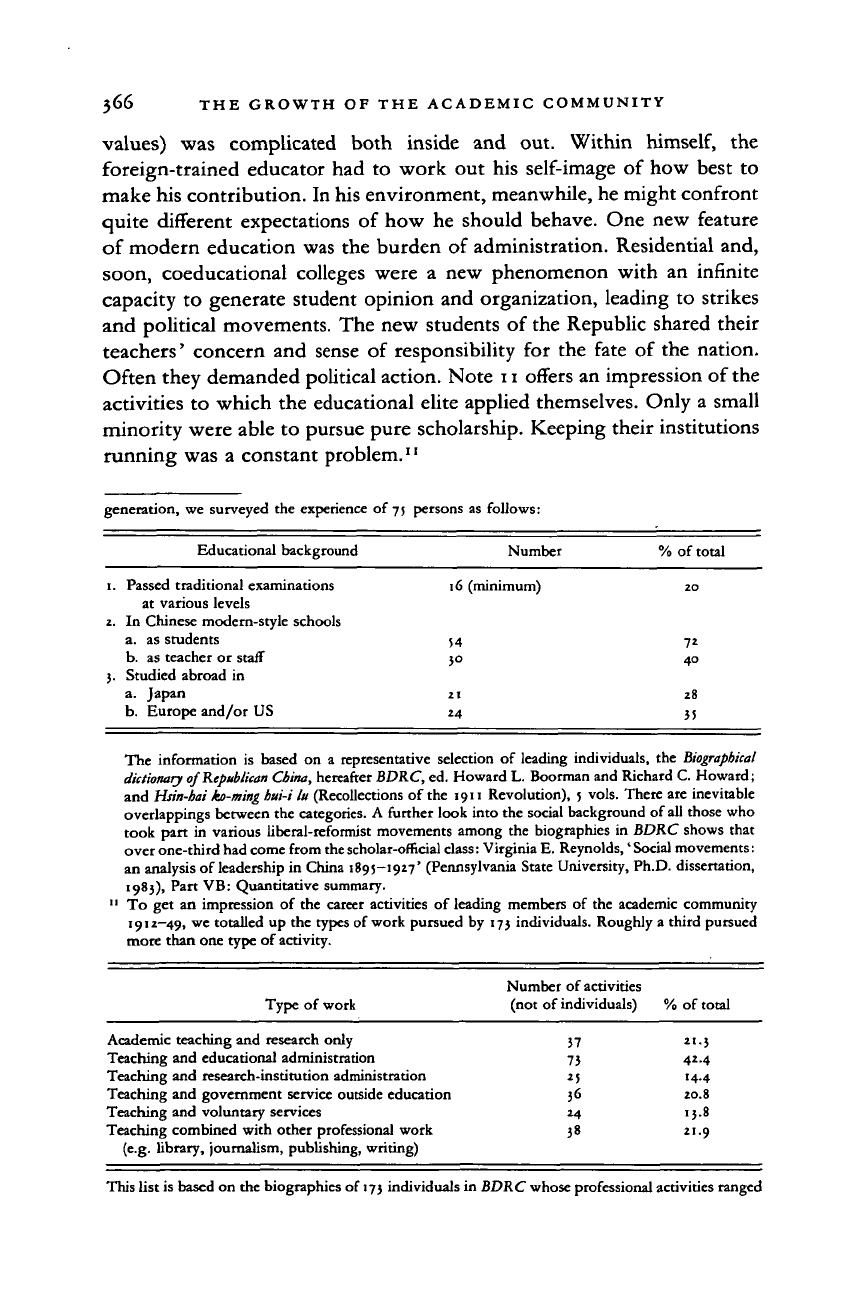

Often they demanded political action. Note 11 offers an impression of the

activities

to

which the educational elite applied themselves. Only

a

small

minority were able

to

pursue pure scholarship. Keeping their institutions

running was

a

constant problem.''

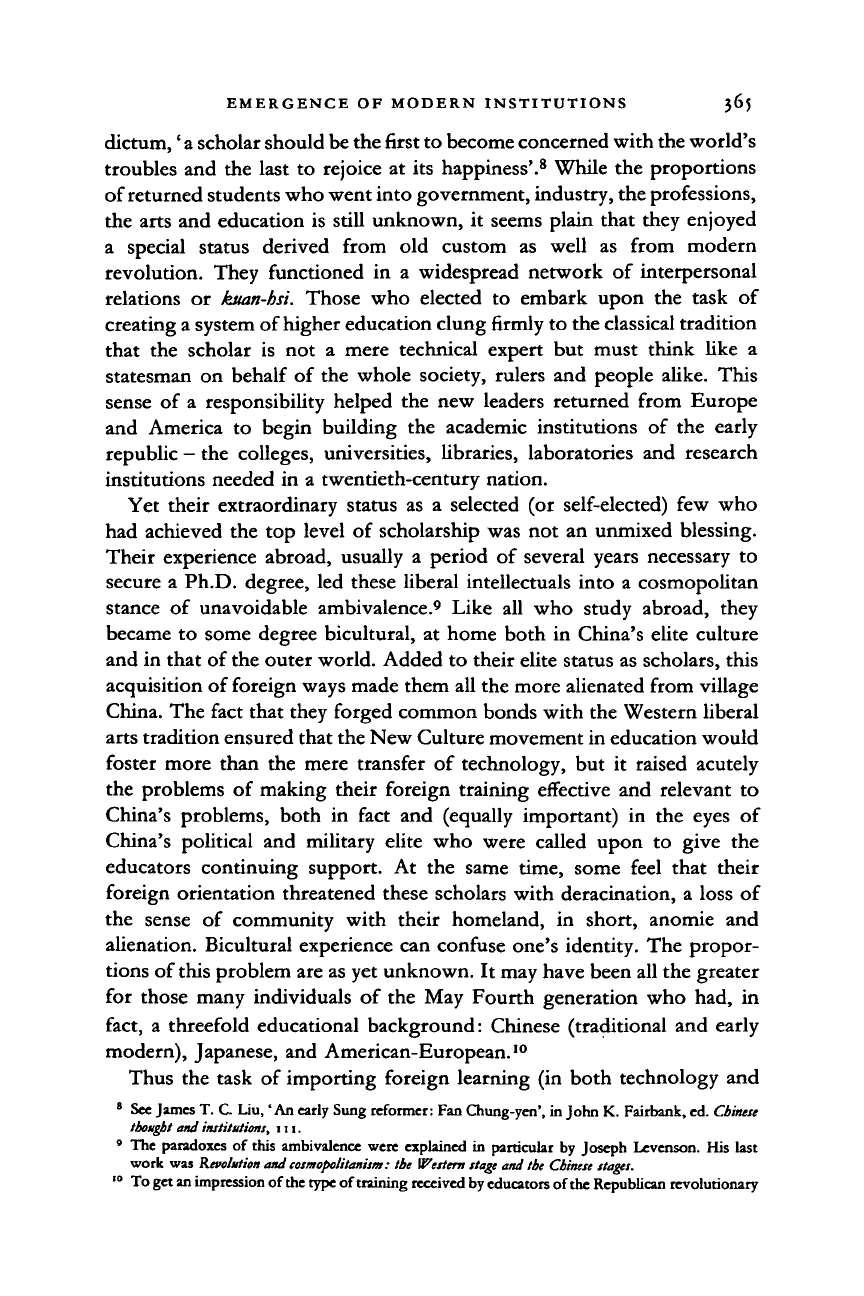

generation,

we

surveyed the experience

of

75 persons

as

follows:

Educational background Number %

of

total

1.

Passed traditional examinations

at various levels

2.

In Chinese modern-style schools

a. as students

b.

as

teacher or staff

3.

Studied abroad

in

a. Japan

b.

Europe and/or US

16 (minimum)

54

3°

21

24

20

72

40

28

35

The information

is

based

on a

representative selection

of

leading individuals,

the

Biographical

dictionary

of

Republican

China,

hereafter BDRC, ed. Howard L. Boorman and Richard C. Howard;

and

Hsin-hai ko-ming hui-i

lu (Recollections

of

the 1911 Revolution), 5 vols. There are inevitable

overlappings between the categories.

A

further look into the social background of

all

those who

took part

in

various liberal-reformist movements among

the

biographies

in

BDRC shows that

over one-third had come from the scholar-official class: Virginia E.

Reynolds,'

Social movements:

an analysis of leadership in China 1895-1927' (Pennsylvania State University, Ph.D. dissertation,

1983),

Part VB: Quantitative summary.

11

To get an

impression

of

the career activities

of

leading members

of

the academic community

1912—49, we totalled up the types

of

work pursued by 173 individuals. Roughly a third pursued

more than one type of activity.

Number of activities

Type

of

work (not

of

individuals) %

of

total

Academic teaching and research only

Teaching and educational administration

Teaching and research-institution administration

Teaching and government service outside education

Teaching and voluntary services

Teaching combined with other professional work

(e.g. library, journalism, publishing, writing)

This list is based on the biographies

of

173

individuals in BDRC whose professional activities ranged

37

73

2!

36

*4

38

21.3

42.4

14.4

20.8

,3.8

21.9

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EMERGENCE OF MODERN INSTITUTIONS 367

Sooner or later the educators also faced as a group the problem of their

relationship

to

political authority. Labouring

in the

shadow

of the

1200-year-old government examination system that was abolished only in

1905,

the Western-trained educators inherited the values and issues that

had concerned preceding generations of Chinese scholars at the same time

that they embraced new values and models met abroad. They succeeded

in creating by the 1930s a more autonomous and diverse system of higher

education, less directly under the thumb

of

the government and

of

an

official orthodoxy. Yet this was

a

temporary situation, due to the lack of

both

a

central government and

an

orthodoxy during the warlord era.

Education

in

China, because

of

the tradition

of

scholar-government,

remained intertwined with politics. Higher education had always been for

the ruling stratum, not for the individual commoner. To divorce

it

from

the ideological orthodoxy of the state would not be easy. Small wonder

that the growth of a more independent type of education separate from

politics was fitful and halting.

Moreover,

in

the early republic education was facilitated not only by

the weakness of central power but also by the pluralistic influence of the

imperialist powers. The interest

of

foreigners

in

China included

the

fostering of modern education both through Christian missionary schools

and colleges

and

through

the

setting

up of

autonomous educational

foundations, both protected

by

extraterritoriality. China's academic

development in 1912-49 may be seen as part of the worldwide growth of

modern learning in which North and South Americans, Russians, Japanese

and Indians

all at

one time

or

another turned

to

Western Europe

for

enlightenment.

Yet one

side-effect

of the

Chinese educated elite's

participation

in the

international world

was its

vulnerability

to the

xenophobic charge

of

being foreign-oriented. This bicultural, bilingual

elite educated in the outside world paid the price of sometimes feeling or

appearing as strangers in their homeland, even as persons in foreign pay.

The psychological and intellectual pressures of their experience in China

and abroad would move some

of

the politically minded wing

of

the

returned-student generation toward Marxism. The academically inclined

wing was also in need of a new system of

belief,

new verities to steer by.

Many educators adopted a fervent belief in the efficacy of

science.

Indeed

the talisman for China's catching up with the outside world became the

universal truth of'

science',

which had figured

in

reformist thinking

of

the 1890s as well as the New Culture movement. China's educators sought

from partial affiliation (such

as

teaching at college level

for

a

short period only) to life-long involvement

with various aspects of higher educational and research institutions. The group is admittedly selective,

but

it

embraces those persons who most actively influenced the growth

of

the modern academic

community.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

368 THE GROWTH OF THE ACADEMIC COMMUNITY

her salvation through the applications of the ' scientific method', not only

in

the

natural

and

social sciences

but in the

humanistic sciences

and

Chinese historical studies as well. For some

it

was

a

tenet of faith which

took

on

almost religious proportions. Wang Feng-chieh,

a

professor of

education, expressed the prevalent attitudes of the 1920s when he declared

that

The old educational system and old national customs have been destroyed. New

education

-

an education based on science

—

has begun... We must realize that

an educational system cannot

be

obtained through imitation,

but

must

be

achieved through deliberation and

experience.

Western ways of education cannot

be transplanted

in

their entirety to China; we must consider the conditions in

China

and

make appropriate choices. Therefore

my

conclusion

is the

new

education must be guided by science: theories should be based on scientific data

and

proof,

practice should follow scientific methods, and the results should be

counted up scientifically.

12

Here were the main themes underlying educational modernization in the

early republic: that the old order had been irrevocably disabled with the

collapse of the imperial system, that China must work to establish a new

system

of

education

of

its own, and

-

following

the

rise

of

the New

Culture movement

-

that ' science' and scientific methods would prove

to be the firmest foundation upon which the new system could be built.

13

Universities: the

creation

of institutions

Bringing young

men and

also women into residential communities

presided over by faculty members was as much an innovation as the rise

of the factory system in industry. Similarly

it

had its forebears in China's

long educational history, though

the

connections have hardly been

explored as yet. The conscious aim of those who built up higher education

was usually to imitate foreign models. But which ones? The choice might

well be influenced by the foreign model's resonance with Chinese needs

or traditions. Unfortunately, while biographical materials are abundant,

institutional histories

are

still

few.

Below

we

look first

at

Peking

University, then at private, technical and Christian institutions, and finally

at the role played by foreign funding.

Peking

University.

In

1912 the new republic inherited from the fallen

Ch'ing dynasty, among other things,

a

small

and

rather uncertain

institution named Ching-shih ta-hsueh-t'ang or' Metropolitan University'.

12

Wang Feng-chieh, Cbung-km

cbiao-ju-shih

ta-ktmg (An outline history

of

Chinese education),

5.

Wang was

at

Ch'en-kuang University in Changsha.

13

On the various views

of

Science'

in

the New Culture movement, see B.

I.

Schwartz's summary

in CHOC 12.424-8, 440; also D. W. Y. Kwok,

Scientism

in

Chinese thought

ifoo—ifjo.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

EMERGENCE OF MODERN INSTITUTIONS 369

Founded during the reforms

of

1898,

it

drew heavily on the modernized

Japanese model while attempting to meet what its founders perceived

to

be an urgent Chinese need: to retrain some of the Ch'ing scholar-officials

so they would be reasonably knowledgeable about affairs and conditions

of the modern world. Surviving the empress dowager's

coup

d'etat of 1898,

this institution was reorganized in 1902 to add a teacher-training division,

and at the same time absorb the Interpreters' College or T'ung-wen kuan,

thus adding five foreign language programmes as well as basic sciences

to the existing curriculum.

14

The students in Peking University at the turn of the century were mainly

officials who enrolled

to

be taught

a

minimum

of

modern subjects, but

even before the 1911 Revolution the assessment of their accomplishments

were extremely low.

15

The quality of the students was uneven. Some, their

minds still firmly imbedded

in

the old civil examination system, treated

their experience

at

the new academy as

a

step toward another qualifying

degree, thereby giving the institution a reputation for decadence. Others,

however, more progressive and venturesome

in

outlook,

in

spite

of

an

environment

of

frivolity and indolence, were genuinely concerned with

current issues, and engaged

in

lively discussions

on

campus.'

6

At the

government level, however, there was still lacking a consensus on higher

educational policy, so there was no progress in developing a coordinated

structure for all levels of the educational system.

After Ts'ai Yuan-p'ei was appointed minister of education in 1912,

he

convened a National Provisional Educational Conference to serve as ' the

starting point of the nation's educational reforms'. Meeting in Peking in

July,

the

delegates from

all the

provinces charted

new

policies

and

regulations

in

response

to

these needs.

17

They concluded that Chinese

14

Ch'iu Yii-lin, 'Ching-shih ta-hsueh-t'ang yen-ko lueh' (A brief history

of

Peking University),

in

Cb'ing-tai

i-aen

(Informal records

of

the Ch'ing period) 5.1-2;

Yu

Ch'ang-lin, 'Ching-shih

ta-hsueh-t'ang yen-ko lueh',

in

Shu Hsin-ch'eng,

Chung-km chin-tai cbiao-yu-sbib

t\u-liao (Source

materials

on

modern Chinese education), 159-60.

On the

Interpreters' College

see

Knight

BiggerstafT,

The earliest

modern

government schools in

China.

After the Boxer Protocol of

1901

attempts

were made

to

establish universities

at

the provincial level, as

in

Shansi under the leadership of

Ku Ju-yung: see Chou Pang-tao,

Cbin-tai cbiao-yu bsien-cbin cbuan-lutb

(Biographical sketches

of

leaders

of

modern Chinese education), first part, 295. However, Brunnert

and

Hagelstrom

recorded in 1910 in their Present day political

organisation

of

China

that there was only one university,

the new one in Peking (p. 225). In the 1920s, year books listed half a dozen provincial institutions

devoted

to

agriculture

or

engineering, e.g. H. G. W. Woodhead, ed. CYB,

1926,

lists them

for

Chekiang, Fukien, Hunan, Kiangsi, Kiangsu and Shantung (434b).

15

Ch'iu Yu-lin, 2; Yu Ch'ang-lin, 160.

16

Yu T'ung-kuei, 'Ssu-shih nien ch'ien wo k'ao-chin mu-hsiao

ti

ching-yen' (How

I

matriculated

in my Alma Mater [Peking University] forty years ago),

in

T'ao Ying-hui, 'Ts'ai Yuan-p'ei yu

Pei-ching ta-hsueh 1917-1923', hereafter T'ao Ying-hui, 'Ts'ai/Peita',

Bulletin

ojthe

Institute

of

Modem History,

;

(1976) 268.

" Wo I, 'Lin-shih chiao-yu-hui jih-chi' (Diary of the Provisional Educational Conference), in Shu

Hsin-ch'eng, 296-7.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

37° THE GROWTH OF THE ACADEMIC COMMUNITY

education was wanting

in

three aspects:

it

needed

to be

built into

a

well-articulated system, extended

to

reach all parts

of

the country, and

brought up to modern standards. Higher education for the first time took

its place,

at

least on paper, as part of an integrated national system.

Within the next two decades there would generally emerge in China

a

number of colleges and universities of diverse types

-

national, provincial,

or private in origin, with varied objectives. Their unfolding story would

reveal, however, that these institutions shared certain characteristics. The

general philosophy was that higher education constituted an indispensable

component

of

the larger task

of

national reconstruction, since

it

would

be the training ground

for

future leaders;

at

the same time, those who

took an active part in developing higher education were young intellectuals

who had studied

in

late-Ch'ing modern schools and become associated

with political movements. As

a

group they generally shared

a

common

origin

as

sons

of

scholar-class families. Many had worked

in

the cause

of the Republican revolution. They came

to

regard each other not only

as fellow-students

of

that period,

but

comrades

as

well

in

pursuit

of

national goals. Thus no one objected

to

Article

I

of the laws governing

colleges and universities officially announced in 1912: 'The objectives of

colleges and universities are

to

instruct [students]

in

advanced learning,

to train knowledgeable experts, and to meet the needs of the nation.'

18

Under the laws

of

1912, higher education

in

universities was

to be

conducted

by a

Faculty

of

Letters and

a

Faculty

of

Science, plus such

professional discipline as business, law, medicine, agriculture and engineer-

ing. To achieve the standing of

a

university an institution must have both

the Faculties

of

Letters and

of

Science,

or a

combination

of

Letters and

Law and/or Business,

or

Science and/or Medicine, Agriculture,

or

Engineering. Peking University, renamed National Peking University

during the chancellorship of Yen Fu, was the sole national university, that

is,

under the direct jurisdiction of the Ministry

of

Education, from 1912

till the end

of

1916.

19

All was not smooth sailing for National Peking University

—

or ' Peita'

for short

—

in its new status; in fact, for five years it was rocked by student

protests, frequent changes

of

chancellor,

and

general uncertainty

of

institutional life,

20

all of which reflected the unsettled political condition

18

Ta-bsutb ling

(Ordinance on colleges and universities), promulgated by the Ministry of Education

in October 1912: see Shu Hsin-ch'eng,

Cbung-kuo chin-tai chiao-jii-sbib

t^u-liao

(Source materials

on modern Chinese education), 647. The 1917 revision

of

the ' Objectives'

in

this ordinance

removed a comma in the statement, so that the new version read ' to train knowledgeable experts

for meeting the needs of the nation'.

Ibid.

671.

"

Ibid.

647; T'ao Ying-hui,

'

Ts'ai/Peita', 271.

20

T'ao Ying-hui,' Ts'ai/Peita',

270-1.

A CCP view of Peita history is presented in Hsiao Ch'ao-jan

et

al.

Pei-cbing

ta-bsutb-bsiao-shih,

iSpt-iptf (A history of Peking University, 1898-1949).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008