Van Huyssteen J.W. (editor) Encyclopedia of Science and Religion

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

EVOLUTION,HUMAN

— 300—

time by adapting to their environments. Those in-

dividuals who are optimally suited to their envi-

ronments end up producing more descendants

than those who are not. If the features that make

them better “adapted” are passed along by biolog-

ical inheritance to their offspring, those features

will become more common in the population,

whose aspect will thus change over time. Keenly

aware of the controversy it would generate, the re-

tiring Darwin minimized any reference to humans

in his publication, and did not broach the problem

of human origins until many years later. Darwin’s

theory of “descent with modification” generated a

great deal of controversy within religious and

scientific communities. The highly public and

politico-religious uproar that resulted centered on

the distasteful suggestion that humans and apes

share a common ancestor, especially in view of the

long held belief that other animals are unable to

think and are effectively nothing more than soul-

less automatons. Coming to Darwin’s defense,

Thomas Henry Huxley (1825–1895) fervently de-

fended the tenets of Darwinian evolution, most

publicly in his debate with Bishop Samuel Wilber-

force (1805–1873) in 1860. In his influential 1863

publication of a series of public lectures titled Evi-

dence as to Man’s Place in Nature, Huxley argued

that humans should be seen as biological organ-

isms, and subject to the same natural laws that all

other organic entities obey.

Interpreting the hominid fossils

The second epochal event for human evolutionary

studies was the 1856 discovery of a fossil human at

the Feldhofer Grotto in the Neander Valley, Ger-

many. Most authorities of the day dismissed this

find as the remains of a “barbarous” type of Homo

sapiens. However, in 1864 the anatomist William

King named the new form Homo neanderthalen-

sis, thereby implying that there had been at least

one ancient human extinction and speciation

event. With further discoveries of the remains of

extinct fossil humans, evolutionary concepts were

more palatably applied to modern humans. The

British geologist Charles Lyell (1797–1875), once a

firm believer in God’s role, abandoned many of his

theological notions and accepted Darwin’s theory

of descent with modification after examining the

remains of the Feldhofer Neanderthal.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the redis-

covery of Mendelian genetics provided a basis for

Darwin’s evolutionary mechanism. Nonetheless,

some paleontologists continued the attempt to

integrate Christian beliefs with the idea of evolu-

tion. One such was the French Jesuit Pierre Teil-

hard de Chardin (1881–1955). While in Jesuit train-

ing in England, Teilhard also trained in

paleontology and archaeology, and became em-

broiled in the Piltdown controversy that was just

erupting. In 1912, he was invited to the Piltdown

site in Sussex, which had yielded fossil bones in-

cluding those of a human, and flint tools. Upon ar-

rival he found a tooth. Reconstruction of the frag-

mentary hominid pieces seemingly offered the

perfect transitional candidate from apes to hu-

mans—perhaps too perfect.

In 1912, “Piltdown Man” was introduced to the

world as Eoanthropus dawsoni. At that time, the

large brain was considered to be the hallmark of

humanity; and for forty years British anatomists

would disregard many significant fossil human dis-

coveries because of their prized and large-brained

Piltdown fossil. Teilhard later continued his pale-

ontological research at the “Peking Man” site of

Zhoukoudian in China. The Chinese fossils helped

Teilhard to reconcile his now expansive knowl-

edge of the human fossil record with his Christian

beliefs. In The Phenomenon of Man (1938–1940),

Teilhard proposed a theory of human evolution in

which humans were evolving towards a final spir-

itual unity, also known as Finalism. This notion

elicited the disapproval of his Jesuit superiors.

Early in the 1950s, Piltdown was exposed as a

hoax—the doctored remains of a human and

orangutan—and Teilhard has even been fingered

as the hoaxer, though he remains only one of the

more unlikely suspects of many. By the late 1950s

the human fossil record had greatly expanded, as

had the plethora of names used to describe it. A

tidying-up was in order, and this was gradually

achieved under a gradualist and progressivist

model of human evolution.

In the 1970s and 1980s, new systematic meth-

ods began to transform the understanding of the

constantly expanding human fossil record. Further,

molecular studies were providing new perspec-

tives. In particular, the “molecular clock” shortened

the ape-human divergence to as little as five to six

million years ago (from maybe twelve to fourteen).

From around 1970 researchers uncovered bipedal

but otherwise rather apelike hominids from sites in

LetterE.qxd 3/18/03 1:05 PM Page 300

EVOLUTION,THEOLOGY OF

— 301—

eastern Africa. These joined the Australopithecus

fossils already known from southern Africa in the

2.5 to 1.5 million years ago range, and dated mostly

from about 3.5 to 2.0 million years ago. Interpreted

using an underlying gradualist model, these ar-

chaically-proportioned fossil hominids mostly re-

flected the search for an “earliest ancestor.”

The situation at the beginning of the

twenty-first century

Over the following few decades, hundreds of fos-

sil human discoveries offered fuel for systematic

debates. The “single species hypothesis,” which

stated that the human ecological niche was so

wide that only one species of hominid could have

existed at any one time, was rapidly invalidated by

new finds, but still lingers in models of human ori-

gins that find deep roots in time for contemporary

geographical groups of humankind. Evolutionary

theory, as well as the rather sparse fossil record,

imply in contrast that the species Homo sapiens

must have had a single origin at one time and in

one place, probably Africa. All of the human di-

versity familiar today has apparently appeared

within the past 150 thousand years or so.

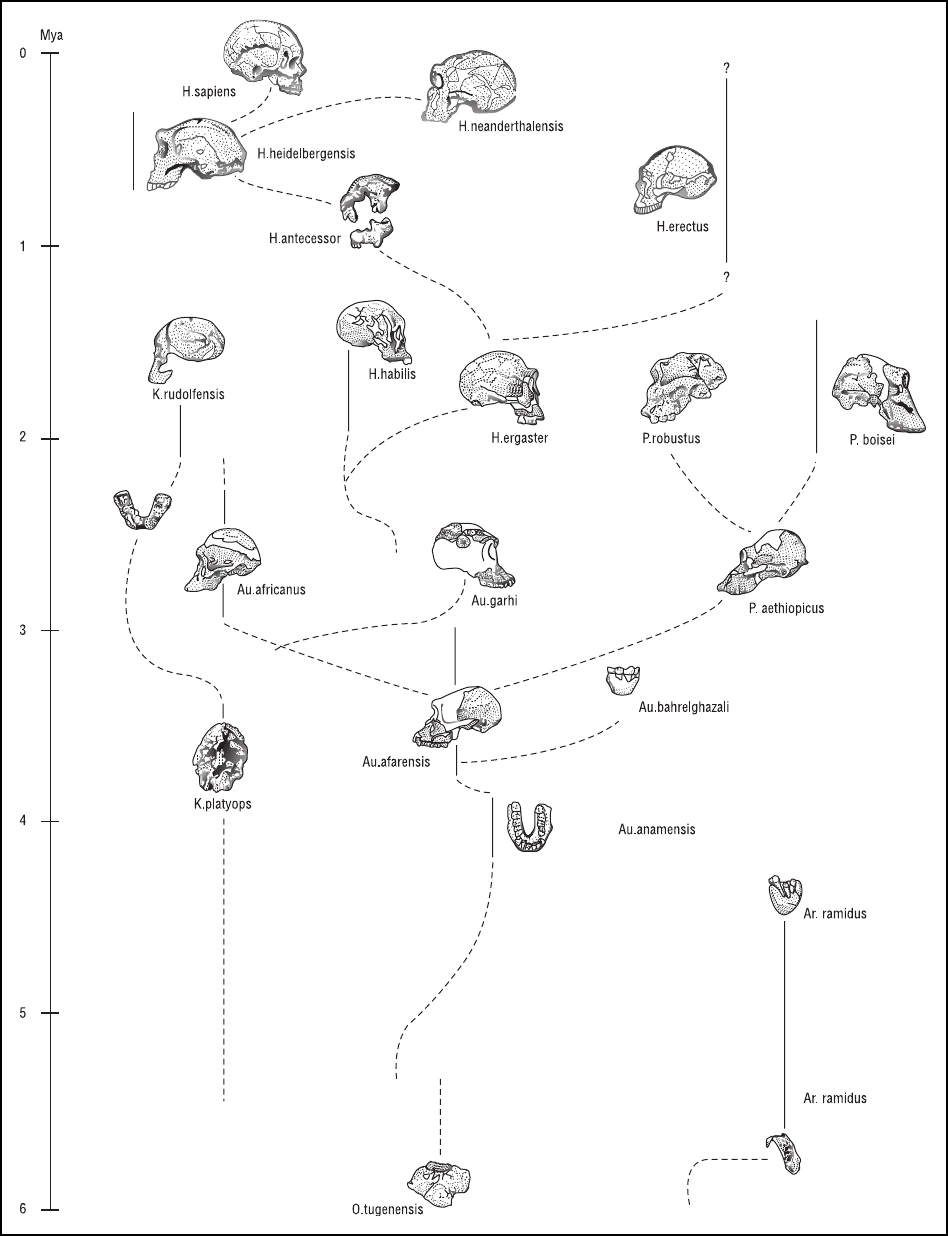

Despite minor differences of opinion, it is clear

that the diversifying pattern of human evolution is

similar to that of other mammalian taxa. Hominid

phylogeny is a story of evolutionary experimenta-

tion, with multiple speciations and extinctions. The

hominid family comprises at least five genera and

eighteen known species (see Fig. 1, p. 302), some

of which shared territories in both time and space.

At present, all geographical varieties of modern hu-

mans occupy the single surviving twig of what ap-

pears once to have been a densely branching bush.

See also ANTHROPOLOGY; EVOLUTION; EVOLUTION,

B

IOCULTURAL; EVOLUTION, BIOLOGICAL;

E

VOLUTION, THEOLOGY OF; PALEOANTHROPOLOGY;

P

ALEONTOLOGY; SOCIOBIOLOGY; TEILHARD DE

CHARDIN, PIERRE

Bibliography

Bowler, Peter J. Evolution: The History of an Idea. Berke-

ley: University of California Press, 1984.

Darwin, Charles. The Origin of Species (1859). New York:

Bantam Classic, 1999.

Eldredge, Niles. The Triumph of Evolution and the

Failure of Creationism. New York: W. H. Freeman,

2000.

Huxley, Thomas Henry. The Major Prose of Thomas Henry

Huxley, ed. Alan P. Barr. Athens: University of Geor-

gia Press, 1997.

Johanson, Donald, and Blake, Edgar. From Lucy to Lan-

guage. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996.

Schwartz, Jeffrey and Tattersall, Ian. Extinct Humans.

Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 2000.

Tattersall, Ian. The Fossil Trail: How We Know What We

Think We Know About Human Evolution. New York:

Oxford University Press, 1995.

Tattersall, Ian. Becoming Human: Evolution and Human

Uniqueness. New York: Harcourt, 1998.

Tattersall, Ian. The Monkey in the Mirror: Essays on the

Science of What Makes Us Human. New York: Har-

court, 2001.

Teilhard de Chardin, Pierre. The Phenomenon of Man.

New York: Harper, 1976.

Wolpoff, Milford. Paleoanthropology, 2nd edition. Boston:

McGraw-Hill, 1999.

KENNETH MOWBRAY

IAN TATTERSALL

EVOLUTION,THEOLOGY OF

The term theology of evolution connotes the sys-

tematic study of the religious implications of bio-

logical evolution. Any intellectually plausible the-

ology today must face the challenges arising from

the notion of life’s common descent and Charles

Darwin’s (1809–1882) theory of natural selection.

The dominant religious and theological tradi-

tions, where they have not been utterly hostile to

it, have generally ignored evolutionary science.

Consequently, when philosophers such as Daniel

Dennett (b. 1942) refer to Darwinian evolution as

“dangerous,” partly because it seemingly destroys

in principle any rational basis for religious life and

thought, theologians must respond to such a

provocation. However, the theological encounter

with Darwinian science is not limited simply to an

apologetic reaction to those scientists and philoso-

phers who interpret evolution in terms of material-

ist philosophy. From the days of Darwin himself

some theologians (for example, the Anglican

Charles Kingsley) have eagerly embraced evolu-

tionary biology as a great gift, one that allows the-

ology to express its understanding of God in fresh

LetterE.qxd 3/18/03 1:05 PM Page 301

EVOLUTION,THEOLOGY OF

— 302—

Figure 1. One view of the diversity of fossil hominid species and of the relationships among them. Courtesy of Ian

Tattersall.

LetterE.qxd 3/18/03 1:05 PM Page 302

EVOLUTION,THEOLOGY OF

— 303—

and fertile ways. In the same spirit a theology of

evolution continues the quest to understand reli-

gious views of deity in light of new scientific in-

formation about the story of life on earth.

That theology can enthusiastically appropriate

evolution, however, may initially seem incompatible

with the apparent randomness, waste, vast temporal

duration, and blind natural selection associated with

Darwin’s theory of “descent with modification.” Ac-

cording to the Darwinian theory, since organisms

produce more offspring than are able to survive,

some of these simply by chance will be better

adapted than others to their habitats. The better-

adapted organisms will on average produce more

offspring than other members of the species, and so

nature will select their descendants for survival.

Over a long period of time this process of natural

selection can account for all of the diversity in life,

as well as for the intricate design in organisms.

The synthesis of Darwinian ideas with the

more recent understanding of genetics, which ex-

plains variations in terms of mutations of genes, is

generally known as neo-Darwinism. In the present

entry, the term evolution will refer to the ideas of

Darwin as well as those of neo-Darwinism.

The theory that all living forms descend with

modification from a single source by way of the

mechanism of natural selection has proven difficult

for many religious people and theologians to em-

brace, especially when natural selection is pre-

sented, as it is by many scientists, as the adequate

explanation of life’s design and diversity. Evolu-

tionists hold that the relative differences that ren-

der one organism more adaptive (reproductively

fit) than others are apparently random or undi-

rected. For theology this raises the question of

whether life in particular, and the universe in gen-

eral, might not be utterly devoid of any providen-

tial guidance. The competitive struggle for survival

between the strong and the weak, in which the

best adapted are selected and the ill-adapted per-

ish, suggests that we live in an indifferent, imper-

sonal universe. The entire process of evolution is

accompanied by what seems to be an enormous

amount of suffering, waste, and an unnecessary

enormity of time, thus making us wonder what

sense we could possibly make of the notion of an

intelligent, compassionate God who truly cares for

life, humans, and the universe.

All of the world’s dominant religious traditions

originated long before we had any inkling of the

fascinating but shocking Darwinian account of

life’s story on earth. It would seem, therefore, that

all of these religions, if they are to remain intellec-

tually persuasive to their scientifically educated

devotees, must now respond to evolutionary biol-

ogy in ways other than simply ignoring or repudi-

ating the neo-Darwinian convictions shared by the

vast majority of contemporary scientists. So, even

though the present entry focuses primarily on the

implications of evolution for Western theology,

much of what is said here may be applicable also

to the religious thought of other traditions as they

begin to look closely at the story of life on Earth.

Theological responses to Darwin

Theological responses to the Darwinian challenge

fall naturally into three classes: opposition, sepa-

ratism, and engagement. Here the first two will be

given only brief treatment, since the third alone

seems to encounter the science of evolution with

the spirit of gratitude and enthusiasm that can lead

to a constructive theology of evolution.

The first response is to insist that Darwinian

evolution is incompatible with any religious or the-

ological vision of the universe. The so-called cre-

ationists and scientific creationists can be located

here. Interpreting the biblical creation accounts lit-

erally, creationists claim that Darwin’s theory offers

a whole new creation story, one that contradicts

the biblical accounts. The idea of evolution seems

to conflict with the accounts in Genesis of human

origins and of the Fall. If there were no historical

Adam and Eve and no “original sin” then, the cre-

ationists ask, what need would there be for a sav-

ior? Scientific creationists go even farther, claiming

that the Scriptures give us a better scientific un-

derstanding of life’s origin than do contemporary

biologists.

Other representatives of this opposition re-

sponse include contemporary proponents of Intel-

ligent Design Theory such as Phillip Johnson,

William Dembski, and Michael Behe. Representa-

tives of this movement are not necessarily biblical

literalists, but they view Darwinism as incompati-

ble with every form of theism. Evolutionary sci-

ence, at least in their view, is inseparable from

philosophical naturalism or scientific materialism, a

vision of reality that explicitly rules out the exis-

tence of God. Johnson, for example, repeatedly as-

serts that Darwinian biology is inherently atheistic

LetterE.qxd 3/18/03 1:05 PM Page 303

EVOLUTION,THEOLOGY OF

— 304—

and that secularists are now using evolutionary

ideas as a weapon in a culture war whose objec-

tive is to topple traditional religious cultures and

concomitant ethical values. Theologians from the

second and third group (discussed below) likewise

observe that at least some prominent Darwinians

present evolutionary science in the guise of mate-

rialist ideology. However, they vehemently reject

the assumption that evolutionary biology is inher-

ently materialistic or atheistic.

The second of the three responses is the sepa-

ratist one. Separatists are those who prefer in gen-

eral to keep theology and science as far apart from

each other as possible. They claim that unneces-

sary confusion on issues in science and religion oc-

curs if we fail to distinguish scientific ideas from re-

ligious beliefs. In their view, theology deals with a

completely different set of questions from those

that scientists are asking. Theology is concerned

with questions about God, human destiny, or ulti-

mate meaning, whereas evolutionary science in-

quires about physical, efficient, material, or me-

chanical—that is, proximate—causes of events in

nature. These two sets of questions, the religious

and the scientific, are so distinct that, logically

speaking, they cannot contradict each other. Con-

sequently, since evolutionary theory is part of sci-

ence, it cannot in principle be placed in a compet-

itive relationship with theology. Many followers of

the neo-orthodox theology of Karl Barth

(1886–1968) as well as existentialist theologians fall

in this separatist camp.

A good number of theologians, philosophers

and scientists are comfortable with this separatist

position. But others question whether this is the

most courageous and fruitful approach that theol-

ogy can take when it comes to evolution. A third

position, engagement, goes further than sepa-

ratism. It endorses the latter’s concern to avoid

conflating or confusing science and religion, but it

advocates a more positive theology of evolution.

Engagement theologians are aware that in the real

world science inevitably affects our theological un-

derstanding. Evolutionary biology, therefore, will

in some way influence our ideas of God. One can

hardly expect to have precisely the same thoughts

about ultimate reality after Darwin as people did

before. Evolution, this third approach suggests, can

even enrich our theological conceptions of God.

Darwin’s great idea, instead of being theologically

dangerous (as the opposition camp holds) or sim-

ply innocuous (as the separatists maintain), may

turn out to be a great stimulus to constructive the-

ology. Recent examples include the contemporary

work of Denis Edwards, John F. Haught, and

Holmes Rolston III.

A theology of evolution does not seek refuge

in pre-Darwinian design arguments, a quest that is

destined to bring theology into unnecessary ten-

sion with science. Scientists, after all, seek to pro-

vide purely natural explanations of design, includ-

ing the ordered complexity of living organisms; so

the attribution of organic design directly to special

divine intervention will be taken as an inappropri-

ate intrusion of theology into an inquiry that lies in

the domain of potential scientific illumination.

Moreover, focus on design may cause us to ignore

the randomness and disorder that accompany the

emergence and evolution of life.

An understanding of God as self-emptying

love, on the other hand, may provide the founda-

tions for an evolutionary theology that neither in-

terferes with scientific exploration nor edits out the

messiness in Darwinian portraits of life. While it is

obliged to reject what it takes to be the deadening

materialist ideology within which neo-Darwinians

often package their popular renditions of evolu-

tion, a theology of evolution based on a kenotic

understanding of God as humble, self-giving love

seems, at least to an increasing number of theolo-

gians, to be consonant with, and illuminative of,

the astounding discoveries of evolutionary science

itself. (The Greek word kenosis literally means

“emptying”).

Prospects for a theology of evolution

Theology, therefore, may begin its reflections on

the life process by asking not whether evolution is

compatible with the idea of an intelligent designer,

but whether the sense of God as it is operative in

actual religious awareness can, without in any way

interfering with scientific work, plausibly contextu-

alize the findings of evolutionary science. A theol-

ogy rooted in actual religious experience is obliged

to understand the natural world, including its evo-

lutionary character, in terms of a specifically reli-

gious notion of God. And so, if the ultimately real

is thought of by religious believers as endlessly

self-emptying compassion, then theology must

LetterE.qxd 3/18/03 1:05 PM Page 304

EVOLUTION,THEOLOGY OF

— 305—

strive to understand Darwinian evolution as some-

how consonant with such an understanding.

Evolutionary scientists, of course, will immedi-

ately want to know how any theology could plau-

sibly reconcile trust in divine providence, the belief

that God provides or cares for the world, with the

fact of randomness or contingency in life’s evolu-

tion. A theology of evolution would not try to

brush this question aside with the reply that the

idea of the “accidental” is simply a cover-up for

human ignorance. Accident or chance is no illu-

sion, but a very real aspect of nature. Moreover, an

element of indeterminacy is just what theology

should expect if the universe is grounded in a God

whose essence, as Christians and others believe, is

self-giving love. For if God really loves the world

as something truly distinct from the divine being it-

self, then the cosmos must always have possessed

some degree of autonomy, even during the long

span of prehuman evolution. As even medieval

philosopher and theologian Thomas Aquinas ob-

served in Summa Contra Gentiles, there has to be

room for contingency and chance in any universe

that is distinct from God.

Not only indeterminacy, however, but also the

remorseless regularity of the laws of nature, in-

cluding natural selection, seems providential. If na-

ture is not to dissolve into chaos at each instant of

its becoming there must be a high degree of con-

sistency to the cosmic process. In this respect, the

impersonal rigidity of natural selection would not

be regarded as any more theologically problematic

than the laws of physics.

Furthermore, if nature is truly distinct from

God, as most theists maintain, a theology of evolu-

tion would not be surprised that nature is given

considerable amplitude for wandering about ex-

perimentally, as evolutionary biology has shown to

be the case with life on earth. If God’s creative and

providential activity includes a liberating posture of

letting the world be something distinct from God,

rather than of manipulatively controlling it, theol-

ogy can hardly be surprised that the world’s cre-

ation does not take place in a single, once-and-for-

all magical moment, but instead takes many

billions of years. The reason theologians give for

this temporal extravagance is that God cannot give

the divine self, in grace and unrestricted love, to a

universe that is not first allowed to be itself, that is,

something truly “other” than God. We may wonder,

then whether a universe created instantaneously in

complete finished perfection would possess the

requisite “otherness” to be loved by its creator.

Of course, to scientists skeptical of theology

the prodigality of evolution’s multi-millennial jour-

ney seems impossible to reconcile with a religious

trust in divine intelligence and providence. Surely,

if God were intelligent and all-powerful, creation

would never have taken so long or ambled so

awkwardly over thirteen or so billions of years.

Here the scientific skeptics would be joined by cre-

ationists and intelligent design defenders in a com-

mon objection: a truly competent creator would

not have gone about the business of creating a

universe in so bumbling a fashion as Darwin’s sci-

ence has pictured it.

However, a theology of evolution would argue

that a God of love wills the independence of the

universe, and that all of the evolutionary indeter-

minacy in the journey of life is consistent with the

idea of a God who longs for a universe of emer-

gent freedom. A theology of evolution would even

claim that any universe embraced by divine love

must inevitably have the opportunity to try out

many different ways of existing. Evolution’s ran-

domness and deep temporal duration, therefore,

are not necessarily signs of a universe devoid of

providence, but are features that could be seen as

essential to the genuine emergence of what is truly

other than God.

A theology of evolution portrays providence,

therefore, as rejoicing in the evolving autonomy of

a self-creating universe. It claims that only a nar-

rowly coercive deity would have collapsed what is

in fact a long and dramatic story of creation into the

dreary confines of a single originating instant. In-

stead of freezing nature into a state of finished per-

fection, a God of love would generously endow the

universe with ample scope to become a self-coher-

ent world rather than letting it be a passive, puppet-

like appendage of deity. A divine providence that

assumes the character of self-humbling love would

risk allowing the cosmos to exist and unfold in rel-

ative liberty. And so the story of life would take on

an evolutionary character not in spite of but be-

cause of God’s care for the cosmos. For this reason,

attempts to cover up the messiness of evolution by

portraits of nature as consisting essentially of order

or design devised by an intelligent designer would

be taken as theologically impoverishing.

LetterE.qxd 3/18/03 1:05 PM Page 305

EXAPTATION

— 306—

A theology of evolution, therefore, revels in

Darwin’s ragged vision of life rather than trying to

trim off its uneven edges. It maintains that evolu-

tion may help theology realize more clearly than

ever that God is more interested in promoting free-

dom and arousing adventure in the world than in

preserving the status quo or legislating impeccable

design. Biblical faith has always been aware of

God’s concern for human liberation. Now evolu-

tionary science allows theology to connect its ideas

of a liberating deity more expansively to the larger

story of life’s ageless emancipation from triviality.

What then about the problems of original sin,

evil, and the fact of suffering in evolution? The idea

of original sin after Darwin cannot refer literally to

events in a historically factual Eden. One interpre-

tation then is that original sin means that each per-

son is born into a world already vitiated by hu-

manity’s habitual turning away in despair from the

imperatives of life and the evolutionary adventure

of self-transcendence. Furthermore, as Jesuit geol-

ogist and paleontologist Teilhard de Chardin

(1881–1955) often noted, as long as the universe

remains unfinished it will have a dark side to it.

Original sin and evil in general cannot be under-

stood apart from the fact that the universe has not

yet been perfected. In this context, one meaning of

sin would be our deliberate resistance to the

world’s ongoing evolution. An unfinished universe

allows for hope, and an evolutionary theology

would claim that the world’s inhabitants are given

the opportunity to participate in the momentous

work of continuing creation. Not to do so would,

in an evolutionary context, be disobedience to the

will of God.

Finally, an evolutionary theology would also

extend the picture of God’s empathy far beyond the

human sphere so as to have it embrace and redeem

all the struggle and pain in the entire emergent uni-

verse. It sees God as responsively enfolding the

whole of creation and not just human history.

See also EVIL AND SUFFERING; EVOLUTIONARY

EPISTEMOLOGY; EVOLUTIONARY ETHICS; HUMAN

NATURE, RELIGIOUS AND PHILOSOPHICAL ASPECTS;

K

ENOSIS; SIN; THEODICY

Bibliography

Darwin, Charles. The Origin of Species (1859). New York:

Bantam Classic, 1999.

Dembski, William. The Design Inference: Eliminating

Chance Through Small Probabilities. New York: Cam-

bridge University Press, 1998.

Dennett, Daniel C. Darwin’s Dangerous Idea: Evolution

and the Meanings of Life. New York: Touchstone,

1995.

Edwards, Denis Edwards. The God of Evolution: A Trini-

tarian Theology. Mahwah, N.J.: Paulist Press, 1999.

Haught, John F. God After Darwin. Boulder, Colo.: West-

view Press, 2000.

Korsmeyer, Jerry D. Evolution and Eden: Balancing Origi-

nal Sin and Contemporary Science. Mahwah, N.J.:

Paulist Press, 1998.

Rolston, Holmes, III. Genes, Genesis, and God: Values

and Origins in Natural and Human History. New

York: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Schmitz-Moormann, Karl. Theology of Creation in an Evo-

lutionary World, in collaboration with James F.

Salmon. Cleveland, Ohio: Pilgrim Press, 1997.

Teilhard de Chardin, Pierre. Christianity and Evolution,

trans. Rene Hague. New York: Harcourt, 1969.

JOHN F. HAUGHT

EXAPTATION

See GOULD, STEPHEN J.; ADAPTATION

EXOBIOLOGY

Exobiology, also known as astrobiology and bioas-

tronomy, is the study of the potential for life be-

yond Earth and the active search for it. Nobel ge-

neticist Joshua Lederberg coined the term

exobiology in 1960, and the field grew significantly

with space exploration, especially the Viking lan-

ders on Mars. Exobiology draws largely from four

disciplines: planetary science, planetary systems

science, origins of life studies, and the Search for

Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI). The field has

been invigorated by claims of fossil life in an an-

cient Mars rock, the discovery of a possible ocean

on the Jovian moon Europa, extrasolar planets

around sun-like stars, life in extreme environments

on Earth, and complex organic molecules in inter-

stellar molecular clouds. Life itself, however, has

not yet been found beyond Earth.

LetterE.qxd 3/18/03 1:05 PM Page 306

EXPERIENCE,RELIGIOUS:COGNITIVE AND NEUROPHYSIOLOGICAL ASPECTS

— 307—

See also

EXTRATERRESTRIAL LIFE

STEVEN J. DICK

EXPERIENCE,RELIGIOUS:

C

OGNITIVE AND

NEUROPHYSIOLOGICAL

ASPECTS

In a neurocognitive approach to the study of reli-

gious and spiritual experiences, it is important to

consider two major avenues towards attaining such

experiences: (1) group ritual, and (2) individual

contemplation or meditation. A phenomenological

analysis reveals that the two practices are similar in

kind, if not intensity, along two dimensions: (1) in-

termittent emotional discharges involving the sub-

jective sensations of awe, peace, tranquility, or

ecstasy; and (2) varying degrees of unitary experi-

ence correlating with the emotional discharges.

These unitary experiences consist of a decreased

awareness of the boundaries between the self and

the external world, sometimes leading to a feeling

of oneness with other perceived individuals,

thereby generating a sense of community.

The experiences of group ritual and individual

meditation overlap to a certain degree, such that

each may play a role in the other. In fact, it may be

that human ceremonial ritual provides the “aver-

age” person access to mystical experience (“aver-

age” in distinction to those who regularly practice

intense contemplation, such as highly religious

monks). This by no means implies that the mystic

or contemplative is impervious to the effects of

ceremonial ritual. Precisely because of the intense

unitary experiences arising from meditation, mys-

tics are likely to be more affected by ceremonial

ritual than the average person. Because of the es-

sentially communal aspect of ritual, it tends to have

immeasurably greater social significance than indi-

vidual meditation or contemplation. However,

meditation and contemplation, almost always soli-

tary experiences, typically produce unitary states

that are more intense and more extended than the

relatively brief flashes generated by group ritual.

Human ceremonial ritual is a morally potent

technology. Depending on the myths and beliefs in

which it is imbedded and which it expresses,

therefore, ritual can either promote or undermine

both the structural aspects of a society and overall

aggressive behavior. In The Ritual Process (1969)

Victor Turner uses the term communitas to refer to

the powerful unitary social experience that usually

arises out of ceremonial ritual. If a myth achieves

its incarnation in a ritual that defines the unitary

experience as applying only to the tribe, then the

result is communitas tribus. It is certainly true that

aggression within the tribe can be minimized or

eliminated by the unifying experience generated

by the ritual. However, this may only serve to em-

phasize the special cohesiveness of the tribe in re-

lation to other tribes. The result may be an increase

in intertribal aggression, even though intra-tribal

aggression is diminished. The myth and its em-

bodying ritual may, of course, apply to all mem-

bers of a religion, a nation state, an ideology, all of

humanity, or all of reality. As one increases the

scope of what is included in the interpretation of

the experience, the amount of overall aggressive

behavior decreases. If indeed a ceremonial ritual

gave flesh to a myth of the unity of all being, then

one would presumably experience a brief sense of

communitas omnium. Such a myth-ritual experi-

ence approaches meditative states, such as the

“cosmic consciousness” described in 1961 by

Richard Bucke, or even the “Absolute Unitary

Being” described in Eugene d’Aquili and Andrew

Newberg’s Mystical Mind (1999). However, such

grand scope is normally unusual for group ritual.

A neurocognitive perspective on spiritual

experiences

It appears that there are a variety of spiritual expe-

riences that may seem to be different, but actually

have a similar neurocognitive origin, and there-

fore, lie along a continuum. This continuum might

be thought of from a unitary experiential perspec-

tive. On one end of the spectrum are experiences

such as those attained through participating in a

church liturgy or watching a sunset. These experi-

ences carry with them a mild sense of being con-

nected with something greater than the self. On

the other end of the spectrum are the types of ex-

periences usually described as mystical or tran-

scendent. This unitary element of spiritual experi-

ence should not be thought of as limiting the

specific aspects and experiences associated with

them. It simply appears to be the case that unitary

LetterE.qxd 3/18/03 1:05 PM Page 307

EXPERIENCE,RELIGIOUS:COGNITIVE AND NEUROPHYSIOLOGICAL ASPECTS

— 308—

feelings are a crucial part of spiritual experiences.

Most scholars have focused on the more intense

experiences because of ease of study and analy-

sis—the most intense experiences provide the

most robust responses, which can be qualitatively

and perhaps even quantitatively measured. For ex-

ample, in “Language and Mystical Awareness”

(1978), Frederick Streng described the most in-

tense types of spiritual experiences as relating to a

variety of phenomena, including occult experi-

ence, trance, a vague sense of unaccountable un-

easiness, sudden extraordinary visions and words

of divine beings, or aesthetic sensitivity. In The Re-

ligious Experience of Mankind (1969), Ninian

Smart distinguished mysticism from an experience

of “dynamic external presence.” Smart argued that

certain sects of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Daoism

differ markedly from prophetic religions, such as

Judaism and Islam, and from religions related to

the prophetic-like Christianity, in that the religious

experience most characteristic of the former is

“mystical,” whereas that most characteristic of the

latter is “numinous.”

Similar to Smart’s distinction between mystical

and numinous experiences is the distinction Walter

T. Stace makes in Mysticism and Philosophy (1960)

between what he calls “extrovertive” and “intro-

vertive” mystical experiences. According to Stace,

extrovertive mystical experiences are characterized

by: (1) a “Unifying Vision” that all things are one;

(2) a concrete apprehension of the “One” as an

inner subjectivity, or life, in all things; (3) a sense

of objectivity or reality; (4) a sense of blessedness

and peace; (5) a feeling of the holy, sacred, or di-

vine; (6) paradoxicality; and (7) that which is al-

leged by mystics to be ineffable. Introvertive mys-

tical experiences are characterized by: (1) “Unitary

Consciousness,” or the “One,” the “Void,” or pure

consciousness; (2) a sense of nonspatiality or non-

temporality; (3) a sense of objectivity or reality; (4)

a sense of blessedness and peace; (5) a feeling of

the holy, sacred, or divine; (6) paradoxicality; and

(7) that which is alleged by mystics to be ineffable.

Stace then concludes that characteristics 3 through

7 are identical in the two lists and are therefore

universal common characteristics of mystical expe-

riences in all cultures, ages, religions, and civiliza-

tions of the world. Characteristics 1 and 2 ground

the distinction between extrovertive and intro-

vertive mystical experiences in his typology. There

is a clear similarity between Stace’s extrovertive

mystical experience and Smart’s numinous experi-

ence, and between Stace’s introvertive mystical ex-

periences and Smart’s mystical experience.

A neurocognitive analysis of mysticism and

other spiritual experiences might clarify some of

the issues regarding mystical and spiritual experi-

ences by allowing for a better typology of such ex-

periences based on the underlying brain structures

and their related cognitive functions. In terms of

the effects of ceremonial ritual, rhythmicity in the

environment (visual, auditory, or tactile) drives ei-

ther the sympathetic nervous system, which is the

basis of the fight or flight response and general lev-

els of arousal, or the parasympathetic nervous sys-

tem, which is the basis for relaxing the body and

rejuvenating energy stores. Together, the sympa-

thetic and parasympathetic systems comprise the

autonomic nervous system, which regulates many

body functions, including heart rate, respiratory

rate, blood pressure, and digestion. During spiri-

tual experiences, there tends to be an intense acti-

vation of one of these systems, giving rise to either

a profound sense of alertness and awareness (sym-

pathetic) or oceanic blissfulness (parasympathetic).

It has also been shown that both the sympathetic

and the parasympathetic mechanism might be in-

volved in spiritual experiences since such experi-

ences contain both arousal and quiescent-like cog-

nitive elements.

For the most part, this neurophysiological ac-

tivity occurs as the result of the rhythmic driving of

ceremonial ritual. This rhythmic driving may also

begin to affect neural information flows through-

out the brain. The brain’s posterior superior pari-

etal lobe (PSPL) may be particularly relevant in this

regard because the inhibition of sensory informa-

tion may prevent this area from performing its

usual function of helping to establish a sense of

self and distinguishing discrete objects in the envi-

ronment. The result of this inhibition of sensory

input could result in a sense of wholeness becom-

ing progressively more dominant over the sense of

the multiplicity of baseline reality. The inhibition of

sensory input could also result in a progressive

loss of the sense of self. Ceremonial ritual may be

described as generating these spiritual experiences

from the “bottom-up,” since it is through rhythmic

sounds and behaviors that rituals eventually drive

the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems and,

ultimately, the higher order processing centers in

the brain. In addition, the particular system initially

LetterE.qxd 3/18/03 1:05 PM Page 308

EXPERIENCE,RELIGIOUS:COGNITIVE AND NEUROPHYSIOLOGICAL ASPECTS

— 309—

activated depends upon the type of ritual. Rituals

themselves might therefore be divided into the

“slow” and the “fast.” Slow rituals involve, for ex-

ample, peaceful music and soft chanting to gener-

ate a sense of quiescence via the parasympathetic

system. Fast rituals might include, for example,

frenzied dancing to generate a sense of heightened

arousal via the sympathetic system.

Individual practices like prayer or meditation

may also access a similar neuronal mechanism, but

from the “top-down.” In such a practice, a person

begins by focusing the mind as dictated by the par-

ticular practice, thereby affecting higher-level pro-

cessing areas of the brain and ultimately the auto-

nomic nervous system. For example, a meditation

practice in which the person focuses on a visual-

ized object of spiritual significance might begin

with activation of the brain’s prefrontal cortex

(PFC), which is normally active during attention-

focusing tasks. The continuous fixation on the

image by the areas of the brain responsible for high

order visual processing begins to stimulate the lim-

bic system, which is primarily involved in emo-

tional processing and memory. Several scholars

have implicated this area as critical for religious ex-

perience because of its ability to label experiences

as profound or real and also because certain patho-

logical conditions, such as seizures in the limbic

areas, have been particularly associated with ex-

treme religious experiences. The limbic system is

connected to a structure called the hypothalamus,

making it possible to communicate the activity oc-

curring in the brain to the rest of the body. The hy-

pothalamus is a key regulator of the autonomic

nervous system, and therefore such activity in the

brain ultimately activates the arousal (sympathetic)

and quiescent (parasympathetic) arms of the auto-

nomic nervous system. Part of the result of medita-

tion and other spiritually oriented practices is also

to block sensory input into the PSPL, resulting in a

loss of the sense of self and a loss of awareness of

discrete objects. Thus, a comparison of ceremonial

ritual and individual practices like meditation sug-

gests that the end result can be the same for both.

It is, of course, difficult to attain the same degree of

spiritual experience through ritual as through med-

itation, because the former requires the mainte-

nance of the rhythmic activity necessary for the

continued driving of neurocognitive systems. How-

ever, ceremonial ritual still can result in powerful

unitary experiences.

The cognitive state in which there is a unity of

all things, including the self, the world, and objects

in the world, is described in the mystical literature

of all the world’s great religions. When a person is

in that state all sense of discrete being is lost and

the difference between self and other is obliterated.

There is no sense of the passage of time, and all

that remains is a timeless undifferentiated con-

sciousness. When such a state is suffused with pos-

itive affect there is a tendency to describe the ex-

perience, after the fact, as personal. Such

experiences may be described as a perfect union

with God, as in the unio mystica of the Christian

tradition, or else the perfect manifestation of God in

the Hindu tradition. When such experiences are ac-

companied by neutral affect they tend to be de-

scribed, after the fact, as impersonal. These states

are described in concepts such as the “abyss” of

Jacob Boeme, the “void” or “nirvana” of Bud-

dhism, or the “absolute” of a number of philosoph-

ical and mystical traditions. There is no question

that whether the experience is interpreted person-

ally as God or impersonally as the “absolute” it

nevertheless possesses a quality of transcendent

wholeness without any temporal or spatial division.

Techniques for studying spiritual

experiences

Clearly, one of the most important aspects of a

study of spiritual experiences is to find careful, rig-

orous methods for empirically testing hypotheses.

One such example of empirical evidence for the

neurocognitive basis of the spiritual experiences

described above comes from a number of studies

that have measured neurophysiological activity

during states in which there is activation of the ho-

listic operator. Meditative states comprise perhaps

the most fertile testing ground because of the pre-

dictable, reproducible, and well-described nature

of such experiences. Studies of meditation have

evolved over the years to utilize the most ad-

vanced technologies for studying neurophysiology.

Originally, studies analyzed the relationship

between meditative states and electrical changes in

the brain as measured by electroencephalography

(EEG). Proficient meditation practitioners have

been shown to demonstrate significant changes in

the electrical activity in the brain, particularly in

the frontal lobes. Furthermore, the EEG patterns of

meditative practice indicate that it represents a

LetterE.qxd 3/18/03 1:05 PM Page 309