Van Huyssteen J.W. (editor) Encyclopedia of Science and Religion

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

INFORMATION THEORY

— 462—

what is designated reality are complex mixtures of

sensory stimulation and intellectual construction.

Software and hardware change the way human be-

ings see the world, first as a matter of program-

ming necessity, and later because the image of the

world they have has been distorted by the infor-

mation-theoretic format. One is also tempted to be-

lieve that the sheer quantity of information avail-

able on the Internet somehow replaces the filtered,

processed knowledge imparted through more tra-

ditional means of dissemination.

IT models and reality

A theology of creation identifies the physical em-

bodiment of persons as playing a major part in the

achievement of the creator’s purpose. Physical em-

bodiment entails certain limitations imposed by

sensory parameters and necessitates certain kinds

of community and cooperation. The nature of the

world comes to be construed in accordance with

certain kinds of gregarious cooperative endeavor.

IT has the power to change the relationship

between human’s perceptual and conceptual sys-

tems and the world. Digital clarity, arising from the

cleansing of data of its inconvenient messiness, en-

courages one to reconfigure the world; virtual

communities encourage one to reconfigure the pa-

rameters of friendship and love; software models

first imitate and then control financial, political,

and military worlds. The beginning of the twenty-

first century is an age when the residual images of

a predigital worldview remain strong; one can still

see that there is a difference. A theology of cre-

ation suggests that this analogical unclarity is de-

liberate and purposive; a digital worldview may

prove more incompatible with that creative story

than currently supposed. The digital reconfigura-

tion of epistemology may yet prove to be the most

profound shift in human cognition in the history of

the world, and the changes impression of reality

that it will afford will present any theology of cre-

ation with a deep new challenge.

See also EMBODIMENT; INFORMATION; INFORMATION

THEORY

Bibliography

Hofstadter, Douglas R. Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal

Golden Braid (1979). London, Penguin, 1996.

Ullman, Ellen. Close to the Machine: Technophilia and Its

Discontents. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1997.

Weizenbaum, Joseph. Computer Power and Human Rea-

son: From Judgment to Calculation (1976). London:

Pelican, 1984.

JOHN C. PUDDEFOOT

INFORMATION THEORY

The version of information theory formulated by

mathematician and engineer Claude Shannon

(1916–2001) addresses the processes involved in

the transmission of digitized data down a commu-

nication channel. Once a set of data has been en-

coded into binary strings, these strings are con-

verted into electronic pulses, each of equal length,

typically with 0 represented by zero volts and 1 by

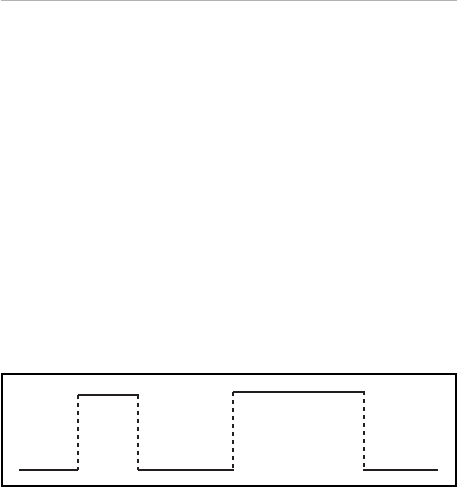

+ 5 volts. Thus, a string such as 0100110 would be

transmitted as seven pulses:

It is clear from the example that the lengths of

pulses must be fixed in order to distinguish be-

tween 1 and 11. In practice, the diagram repre-

sents an idealized state. Electronic pulses are not

perfectly discrete, and neither are the lengths of

pulses absolutely precise. The electronic circuits

that generate these signals are based upon ana-

logue processes that do not operate perfectly, and

each pulse will consist of millions of electrons

emitted and controlled by transistors and other

components that only operate within certain toler-

ances. As a result, in addition to the information

sent intentionally down a channel, it is necessary

to cater for the presence of error in the signal; such

error is called noise.

This example illustrates the dangers inherent in

the differences between the way one represents a

process in a conceptual system and the underlying

physical processes that deliver it. To conceive of

computers as if they operate with perfectly clear 0

and 1 circuits is to overlook the elaborate and ex-

tensive error-checking necessary to ensure that

LetterI.qxd 3/18/03 1:06 PM Page 462

ISLAM

— 463—

data are not transmitted incorrectly, which is ex-

pensive both in time and cost.

In 1948, Shannon published what came to be

the defining paper of communication theory. In this

paper he investigated how noise imposes a funda-

mental limit on the rate at which data can be trans-

mitted down a channel. Early in his paper he wrote:

The fundamental problem of communica-

tion is that of reproducing at one point ei-

ther exactly or approximately a message

selected at another point. Frequently the

messages have meaning; that is they refer

to or are correlated according to some sys-

tem with certain physical or conceptual

entities. These semantic aspects of com-

munication are irrelevant to the engineer-

ing problem. (p.379)

The irrelevance of meaning to communication

is precisely the point that encoding and the trans-

mission of information are not intrinsically con-

nected. Shannon realized that if one wishes to

transmit the binary sequence 0100110 down a

channel, it is irrelevant what it means, not least be-

cause different encodings can make it mean almost

anything. What matters is that what one intends to

transmit—as a binary string—should arrive “exactly

or approximately” at the other end as that same bi-

nary string. The assumption is that the encoding

process that produces the binary string and the de-

coding process that regenerates the original mes-

sage are known both to the transmitter and the re-

ceiver. Communication theory addresses the

problems of ensuring that what is received is what

was transmitted, to a good approximation.

See also INFORMATION; INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

Bibliography

Shannon, Claude E. “A Mathematical Theory of Communi-

cation.” The Bell System Technical Journal 27 (1948):

379–423, 623–656.

JOHN C. PUDDEFOOT

INTEGRATION

See also SCIENCE AND RELIGION, MODELS AND

RELATIONS; SCIENCE AND RELIGION,

M

ETHODOLOGIES

INTELLIGENT DESIGN

Intelligent Design is the concept that some things—

especially some life forms or parts of life forms—

must have been assembled (at least for the first

time) by the direct action of a non-natural agent.

Proponents of Intelligent Design argue that there is

empirical evidence that the universe’s system of

natural capabilities for forming things is inadequate

for assembling certain information-rich biological

structures. And if the system of natural capabilities

is inadequate, then these biological structures must

have been assembled by the action of some non-

natural agent, usually taken to be divine.

See also CREATION; CREATIONISM; CREATION SCIENCE;

D

ESIGN; EVOLUTION; SCOPES TRIAL.

HOWARD J. VAN TILL

INTERNET

See INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

ISLAM

Six centuries after Jesus Christ, the religion of Islam

was born in Arabia. By the beginning of the

twenty-first century, Muslims, as its followers have

always called themselves, number more than 1.2

billion worldwide.

According to Muslim tradition, in 611

C.E.at

the age of forty, Muhammad of Mecca received a

revelation from God during a spiritual retreat in a

cave on Mount Hira outside the city. God’s special

envoy who brought the message was the

archangel Gabriel. At Gabriel’s instruction, the illit-

erate Muhammad recited five short verses that por-

trayed the spirit of the new religion. In this first

revelation, Muhammad—thus by extension all hu-

mans—is called upon to know the unknown in the

name of God, whose nature is to create things. Hu-

mans are then reminded of how, from their lowly

animal origin, they became thinking and knowing

creatures thanks to God’s generous gifts of instru-

ments of knowledge that are best symbolized by

the pen. Knowledge is the supreme symbol of

LetterI.qxd 3/18/03 1:06 PM Page 463

ISLAM

— 464—

God’s infinite bounty and the key to his treasuries.

Through sacred knowledge—that is, knowledge

through and for the sake of God—humans can at-

tain salvation. In thus emphasizing the saving func-

tion of knowledge, Muhammad’s maiden revela-

tion as well as many other revelations that were to

follow, clearly portrayed the new faith as a way of

knowledge. As for Muhammad himself, as told by

Gabriel, he had been chosen as the new messen-

ger of God. Fourteen centuries later, Muhammad is

widely regarded as one of the world’s most influ-

ential persons.

Revelations came intermittently to Muhammad

over a period of twenty-three years. All of these

revelations were systematically compiled into a

book known as the Qurhan. According to tradition,

the precise arrangement of the Qurhan itself was di-

vinely inspired. This book is central to the religion.

It is the most authentic and the most important

source of teachings of the religion. The Qurhan is

the most influential guide to Muslim life and

thought, both individual and collective, spiritual

and temporal.

Submission and faith

The word Islam means “surrender or submission”

to God’s will. It also means “peace.” In a sense, it

is through submission to the divine will that a

human attains inner peace. One who submits to

the divine will is called Muslim. In the Qurhan, the

word Muslim refers not only to humans but also to

other creatures and the inanimate world. From the

Qurhanic point of view, this is not surprising. The

divine will manifests itself in the form of laws both

in human society and in the world of nature. In Is-

lamic terminology, for example, a bee is a Muslim

precisely because it lives and dies obeying the

shav3rah that God has prescribed for the commu-

nity of bees, just as a person is a Muslim by virtue

of the fact that he or she submits to the revealed

“shav3rah” ordained for the religious community.

In fact, the Qurhan maintains that “every animal

species is a community like you,” thus implying

that God has promulgated a law for each species

of being. From its beginning, Islam never made

any distinction between what has generally been

known in the Western tradition as the “laws of na-

ture” and “the laws of God.” In principle, there is

harmony between the laws of natural phenomena

(n1m5s al-khilqah) and the laws of the prophets

governing human societies (n1wam5s al-anbiy1)

since both kinds of laws come from the same

source: God the Law-Giver. In asserting such a

view, Islam provides an illustrative example of

how it seeks to establish points of convergence in

the encounter of religion and science.

Islam is noted for the simplicity of its teach-

ings. By professing the testimony of faith “There is

no god but God, and Muhammad is the Messenger

of God,” one enters into the fold of Islam. The

whole teachings of the religion are summarized in

the six articles of faith (ark1n al-3m1n) and the

five pillars of submission (ark1n al-isl1m). Muslims

must believe in six fundamental truths: God, an-

gels, revealed books, divine messengers, life in the

hereafter, and divine plans and decrees. Necessary

beliefs go hand in hand with necessary actions,

since a human is both a thinking and a believing

creature and a creature who acts and does all kinds

of things. There are five fundamental obligatory

duties for every Muslim, male and female:

(1) To bear witness that “There is no god but

God,” and to bear witness that “Muhammad

is the Messenger of God”;

(2) To perform five daily prayers;

(3) To fast from dawn to dusk during the month

of Ramadan;

(4) To pay personal and property tax (zak1t, lit-

erally meaning purification);

(5) To perform pilgrimage (*ajj) in Mecca once

in a lifetime, if possible.

The rest of the teachings of the religion are

consequences and further elaborations of these pil-

lars of the faith and devotional practices.

Allah and the Qurhan

God, or All1h in Arabic, is of course the most fun-

damental reality on which the religion of Islam is

based; God created the Muslim soul and shaped

the Muslim’s thoughts and consciousness. Islam

has come to reaffirm the monotheisms of Adam

and Abraham. God is absolutely one; the origin

and the end of the universe; its creator, sustainer,

and ruler. Allah has created the universe for the

sake of humans, the best of all creatures. A human

being’s purpose of existence is in turn to know

God. By knowing the universe, humans can know

God. This is possible, since God has imprinted nu-

merous signs in the universe. One can also say that

LetterI.qxd 3/18/03 1:06 PM Page 464

ISLAM,CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN SCIENCE AND RELIGION

— 465—

God has imprinted “names” in creation, which are

many. Muslim tradition speaks of ninety-nine

beautiful names of God, the most mentioned in

the Qurhan and the most uttered by the Muslim

tongue being Al-Rahm1n (The Most Compassion-

ate). Muslims adore and celebrate these divine

names in numerous ways. Children in kinder-

gartens and Muslim schools called madrasahs

memorize them by reciting them with melodious

voices in a chorus. Artists visualize them with their

beautiful Arabic calligraphies. Philosophers exert

their intellects to penetrate the deeper meanings of

these names through their profound conceptual

analysis. Mystics or Sufis contemplate them in their

spiritual retreats so that “the heart is empty of

everything except God.” Such is the profound im-

pact of the divine names as conceived by Islam on

the Muslim soul and intellect.

The role of the Qurhan in Muslim life is insep-

arable from that of Muhammad. He is seen as the

perfect embodiment of the Qurhan. A husband and

father, a teacher and a businessman, a leader in

war and peace, and most of all a spiritual and

moral guide, Muhammad is thus the role model

for every Muslim of every generation. In Muham-

mad’s own words, his community of believers will

not err as long as they are guided by the Qurhan

and his way of life.

See also AVERRÖES; AVICENNA; GOD; ISLAM, HISTORY

OF

SCIENCE AND RELIGION; ISLAM, CONTEMPORARY

ISSUES IN SCIENCE AND RELIGION; LIFE AFTER

DEATH; SOUL

Bibliography

Azzam, A. Rahman. The Eternal Message of Muhammad.

Cambridge, UK: Islamic Texts Society, 1993.

Bakar, Osman. Classification of Knowledge in Islam. Cam-

bridge, UK: Islamic Texts Society, 1997.

Bakar, Osman. The History and Philosophy of Islamic Sci-

ence. Cambridge, UK: Islamic Texts Society, 1999.

Esposito, John L. Islam: The Straight Path. New York: Ox-

ford University Press, 1991.

Gulen, M. Fethullah. The Essentials of Islamic Faith.

Konak, Turkey: Kaynak, , 1997.

Hamidullah, Muhammad. Introduction to Islam. Gary,

Ind.: International Islamic Federation of Students Or-

ganizations, 1970.

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. Ideals and Realities of Islam.

Chicago: Kazi Publications, 1997.

Schuon, Fritjhof. Understanding Islam. Bloomington, Ind.:

World Wisdom Books, 1994.

OSMAN BAKAR

ISLAM,CONTEMPORARY

ISSUES IN S

CIENCE AND

RELIGION

In the nineteenth century, the Muslim world’s en-

counter with modern science took the form of a

double challenge, simultaneously material and in-

tellectual. The Ottoman Empire’s defense against

the military rise of Western countries, followed by

successful colonization, made it necessary to ac-

quire Western technology, and, therefore, the sci-

ence behind it. The pressure of modern science on

Islam has remained very strong. The West appears

as the model of progress that the Muslim world has

to reach, or at least follow, through the training of

technicians and engineers and through the massive

transfer of those technologies that are key to de-

velopment. But more than anything else, the en-

counter of Islam with modern science stimulated

philosophical and doctrinal thinking, provoked in

some fashion by an inaugural event, the now fa-

mous lecture titled “Islam and Science,” which

Ernest Renan (1823–1892) delivered at the Sor-

bonne in 1883. In the lecture, where he expressed

his own positivist perspective, Renan criticized the

Muslims’ utter inability to produce scientific dis-

coveries, as well as their supposed inability to

think rationally. Intellectual Muslims of the time,

who were in contact with the Western intelli-

gentsia, considered the lecture offensive. Those in-

tellectuals, with precursor Jamal-al-Din al-Afghani

(1838–1897), then championed the idea that Islam

never experienced a rupture between science and

religion, whereas Christianity, and especially

Catholicism, had known a long period of conflict

with science. They argued that modern science is

nothing other than “Muslim science” developed

long ago in the classical era of the Umayyad and

Abbasid caliphates, and finally transferred to the

West in thirteenth-century Spain, thanks to transla-

tions that later would make possible both the Re-

naissance and the Enlightenment.

For the intellectuals who founded the “mod-

ernist” movement within Islam, there is nothing

wrong, in principle, with science. What remains

LetterI.qxd 3/18/03 1:06 PM Page 465

ISLAM,CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN SCIENCE AND RELIGION

— 466—

unacceptable, however, are the distortions im-

posed upon science by the materialistic and posi-

tivist views held by Western philosophers and an-

tireligious scientists. Modern science could not

emerge in the Muslim world, even though it was

quite advanced at a certain time, because of “su-

perstitions” that were added to the original religion

and encouraged quietist fatalism more than action.

The result of this awakening of consciousness as to

the progressive slipping into torpor (jum5d) of Is-

lamic societies is the modernists’ call for a renais-

sance (nah#ah) through reform (I’l1*) of Islamic

thinking.

Muslim intellectuals who study relationships

between science and religion draw their ideas from

Islam’s epistemology. Indeed, Islamic tradition em-

phasizes the search for “knowledge” (hilm), a word

that recurs more than four hundred times in the

Qur’an and in many prophetic traditions in such

forms as “the search for knowledge is a religious

obligation,” or “search for knowledge all the way

to China.” This knowledge has three aspects: reli-

gious knowledge transmitted through revelation,

knowledge of the world acquired through investi-

gation and meditation, and knowledge of a spiri-

tual nature granted by God. Different attitudes

about the relationship between science and reli-

gion proceed from the different emphases placed

on those three aspects. The word (âyât) describes

both God’s signs in the cosmos and the verses in

the Qur’anic text. Many passages, called “cosmic

verses” (âyât kawniyyah) by commentators, direct

the reader’s attention to nature’s phenomena,

where the reader is to learn to decipher the cre-

ator’s work. Islam’s fundamental perspective is to

affirm divine uniqueness (taw*3d), which ensures

oneness of knowledge, insofar as all true knowl-

edge leads back to God. Therefore, there could

not be disagreement between data resulting from

knowledge of the world and data delivered

through revelation, nor could there be the “double

truth” (duplex veritas) condemned in the Western

medieval world and falsely attributed to Muslim

philosophers.

The fundamental idea of oneness of knowl-

edge appears in the positions of two major players

in the history of Muslim thinking, whose works are

still very much read today. Ab5 H1mid al-Ghazâl

(1058–1111), in The Deliverer from Error (al-

Munqidh min3 a#-Dalâl), champions that rational

certitude is granted by divine gift. If there is dis-

agreement between the results of falsafah (philos-

ophy and science of Hellenic inspiration) and the

teachings of religious tradition, it is because

philosophers took their investigations outside the

domain of validity of their own fields, which led

them to enunciate flawed propositions. In the long

test-case opinion ( fatwá)—the format he used in

his book, On the Harmony of Religion and Philos-

ophy (Kit1b Fa’l al-Maq1l)—Ab5 al-Wal3d Muham-

mad Ibn Rushd (1126–1198) states that the practice

of philosophy and of science is a canonical reli-

gious obligation. For him, if there is apparent dis-

agreement between philosophy and revelation,

then religious texts must be subjected to interpre-

tation (ta’wil) or risk impiety by making God say

things that are manifestly false. Contemporary Mus-

lim positions on science fall into three main cate-

gories that keep to the idea, in one way or another,

of the oneness of knowledge.

The majority position considers, in step with of

the reformers of the nineteenth and twentieth cen-

turies, that there is nothing essentially bad about

science. The West, the current producer of scien-

tific discoveries, may be blamed only for its mate-

rialistic vision and its indifference to morals. What

this trend identifies as science are essentially the

natural sciences, not human sciences permeated

with the West’s antireligious values. Science is con-

sidered as the means to convey “facts” that are, in

essence, totally neutral. What the West lacks is the

sense of ethics that some Western scientists exhibit

personally, but which is not visible enough or at all

in Western societies. Some great Muslim scientists,

such as Mohammed Abdus Salam (1926–1996),

who won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1979, have

advocated the development of modern science in

the Muslim word. Such defenders of science evoke

the glorious hours of the great period of science in

Islam, invoke the long list of Muslim scientists

whom “history forgot,” and strive to build a future

that promotes the emancipating role of education.

This trend has enjoyed considerable growth,

while being used, in some fashion, for apologetic

purposes. In 1976, Maurice Bucaille, a French sur-

geon, released The Bible, the Qur’an, and Science,

a study of the scriptures “in light of modern knowl-

edge,” and concluded the Qur’an to be authentic

because of “the presence in the text of scientific

exposés which, examined in our times, are a chal-

lenge to human analysis” (p. 255). The original in-

tent was not to tackle the relationships between

LetterI.qxd 3/18/03 1:06 PM Page 466

ISLAM,CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN SCIENCE AND RELIGION

— 467—

science and religion in Islam but rather to take part

in the debate between contemporary Orientalists

and Islamists on the status of the Qur’an and to

bring into the debate elements supporting its au-

thenticity. This idea of the “scientific evidence” of

the truth of the Qur’an spread through the Muslim

world with the many translations of Bucaille’s

work, and it became amplified to the point of

being a major force in contemporary Muslim

apologetics, where the traditional theme of “the

inimitability of the Qur’an” (ihj1z al-qur’1n) is fully

reinterpreted from the perspective of “Qur’anic sci-

ence.” Throughout, “Western scientists” identify in

the Qur’an the latest discoveries of modern science

(cosmology, embryology, geophysics, meteorol-

ogy, biology), thereby affirming the truth of Islam.

The supporters of this position hold a concept of

science that gives no thought to its vision of the

world, nor to its epistemological or methodological

presuppositions. Some go even further, when—

calling on the scripture to deliver quantitative sci-

entific information, such as the very precise meas-

ure of the speed of light—they claim to be

founding an “Islamic science” on entirely new

methods. But, as physicist Pervez Hoodbhoy

points out in his Islam and Science (1991), which

takes a stand against such diversion, “specifying a

set of moral and theological principles—no matter

how elevated—does not permit one to build a new

science from scratch” (p.78). There is only one way

to make science, and “Islamic science” of the glo-

rious past was nothing but universal science being

practiced by scientists belonging to the Arab-

Islamic civilization.

View of the presuppositions of modern

science

The second trend rejects this idea of universal sci-

ence and emphasizes the necessity of examining

the epistemological and methodological presup-

positions of modern science of Western origin.

These presuppositions may not be accepted by the

Muslim world. This trend has its roots in critics

from philosophy and history of science. Karl Pop-

per (1902–1994), Thomas Kuhn (1922–1996), and

Paul Feyerabend (1924–1994) contributed, each in

his way, to questioning the notion of scientific

truth, the nature of experimental methods, and the

independence of science’s productions with regard

to the cultural and social environment in which

they appear. In a climate heavily influenced by the

relativism and antirealism of postmodern decon-

struction, Muslim critics of Western science reject

the idea that there is only one way to pursue sci-

ence. They strive to define founding principles for

an “Islamic science” by planting scientific knowl-

edge and technological activity in the ideas of Is-

lamic tradition and the values of religious law

(shar3hah), but with nuances that result from dif-

ferences of interpretation.

That is how Isma’il Raji Al-Faruqi (1921–1986)

elaborated a program of Islamization of knowl-

edge, carried out with the creation in 1981 in Hern-

don, Virginia, of the International Institute of Is-

lamic Thought (IIIT), in response to the

experiences and the thinking of Muslims working

in North American universities and research insti-

tutes. This program is based on the observation of

a malaise within the Muslim community (ummah),

which originates in the importation of a vision of

the world totally foreign to the Muslim perspective.

For the IIIT, the Islamization of knowledge is all

encompassing: It starts with God’s word, which

can and must apply to all areas of human activity,

since God created man as his “representative” or

“vice-regent on Earth” (khalif1t All1h f3 al-ard).

The IIIT’s work leads to the conception of a proj-

ect for the development of a scientific practice at

the heart of a religious vision of the world and of

society. In fact, the IIIT’s undertaking aims more at

the social sciences than at the natural sciences,

which are considered to be more neutral from the

standpoint of methodology.

Other intellectuals, such as Ziauddin Sardar

(1951– ) and the members of the more or less in-

formal school of thought known as ijm1l3 (self-

designated in this fashion in reference to the “syn-

thetic” vision it offers), are also aware of the threat

that the West’s vision of the world, as it is con-

veyed by science, represents for Islam. Deeply in-

fluenced by Kuhn’s analysis of scientific develop-

ment, they note that Western science and

technology are not neutral activities but partake of

a cultural project and become a tool for the dis-

semination of the West’s ideological, political, and

economic interests. To import modern science and

technology into Islam, one needs to rebuild the

epistemological foundations of science, keeping in

mind the perspective of interconnections between

the various domains of human life—a perspective

that is peculiar to Islam. Sardar himself has com-

pared the ijmalis’ position to al-Ghaz1l3’s.

LetterI.qxd 3/18/03 1:06 PM Page 467

ISLAM,CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN SCIENCE AND RELIGION

— 468—

Assessment of the metaphysical foundations

of science

The third trend in Islamic thought is characterized

by a deep assessment of the metaphysical founda-

tions that support the vision of the world sug-

gested by Islamic tradition. Seyyed Hossein Nasr

(1933– ) is its most important proponent. He has

been a champion of a return to the notion of “Sa-

cred Science.” This trend originates in the criticism

of the modern world put forth by French meta-

physicist René Guénon (1886–1951), and later by

authors in his wake, such as Frithjof Schuon

(1907–1994) and Titus Burckhardt (1908–1984), all

Muslims of Western origin. Guénon explained how

modern Western civilization is an anomaly insofar

as it is the only civilization in the world that devel-

oped without reference to transcendence. Guénon

mentions the universal teaching of humanity’s reli-

gions and traditions, all of which are nothing but

adaptations of the original—essentially metaphysi-

cal—tradition. The destiny of human beings is the

intellectual knowledge of eternal truths, not the

exploration of the quantitative aspects of the cos-

mos. In this context, Nasr denounces not so much

the malaise of the Muslim community, but rather

that of Western societies that are obsessed with de-

veloping a scientific knowledge anchored in a

quantitative approach to reality and in the domi-

nation of nature, which results in its pure and sim-

ple destruction.

Nasr’s position and that of the other defenders

of this traditional trend—which some chose to call

perennialist (in reference to Sophia perennis, the

“eternal wisdom” of divine origin, which they per-

petuate)—inscribes itself not only in the critique of

Western epistemology, but in a deep calling into

question of the Western idea of a reality reduced to

matter alone. The perennialists propose a doctrine

of knowledge as a succession of epiphanies, where

truth and beauty appear as complementary aspects

of the same ultimate reality. They call for a return

to a spiritual view of the world and the rehabilita-

tion of a traditional “Islamic science,” which would

preserve the harmony of the being within creation.

In contrast, critics of such a radical position de-

nounce its elitism and emphasize the difficulty of

implementing its program in current circumstances.

The various currents within contemporary

Muslim thinking are evidence of the intense ques-

tioning of the relationship between science and re-

ligion. In this context, the Muslim academic world

has been operating as a kind of melting pot, where

numerous ideas of Islamic or Western origin are

elaborated anew in an effort to synthesize them.

The fundamental elements remain true to Islamic

thinking: the repeated affirmation of God’s unique-

ness, which unites both creation and humanity; the

open nature of the very process of acquisition of

knowledge of the world, which, by essence, is un-

limited since it originates and ends in the knowl-

edge of God; the narrow interconnection of

knowledge and ethics; and, finally, the responsi-

bility of human beings on Earth in their capacity as

vice-regents, who must use the world but not

abuse it and behave as good gardeners must in

their garden. In addition, the metaphysics underly-

ing epistemology and ethics is deeply marked by

the dialectic of the visible and of the invisible. Phe-

nomena are the signs of divine action in the cos-

mos. In fact, God is present in the world, the cre-

ation of which God ceaselessly “renews” at every

moment (tajd3d al-khalq). The articulation of this

form of “opportunism” with causality—and mod-

ern science’s determinism and indeterminism—re-

mains to be elaborated.

Critical thinking on the very elaboration of sci-

ence as an activity marked by culture is now part

of the discourse. In contrast, one must acknowl-

edge that the latest developments in contemporary

science—notably those dealing with mathematical

undecidability, the uncertainty of quantum physics,

the unpredictability of chaos theory, as well as the

questioning by biology of evolution, and by neu-

roscience of conscience—need, no doubt, some

further thinking. Indeed, these developments may

provide interesting ways to shatter the reductionist

and scientist view of the world. They constitute a

kind of cornerstone for a metaphysics and episte-

mology that could give meaning to science as it is

done in laboratories and research institutes.

Finally, one has to provide content to the term

Islamic science. The issue is simultaneously one of

ethics (personal and collective), of epistemology,

and of the metaphysical Weltanschauung it pre-

supposes. When passing from theory to practice,

each current of thought must face specific prob-

lems resulting not only from its specific position

but also from the Muslim world’s economic and so-

cial difficulties. What remains to be established is

the degree to which the most ambitious project—

that of Islamic science as Sacred Science—can

amount to more than a nostalgic glance at the past

LetterI.qxd 3/18/03 1:06 PM Page 468

ISLAM,HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND RELIGION

— 469—

and move on to the stage of its actual implementa-

tion by a spiritual and intellectual elite. The future

of the Islamic civilization’s contribution to the de-

velopment of universal knowledge is tied to the

answer that will be given to that question.

See also AVERROËS; AVICENNA; ISLAM; ISLAM, HISTORY

OF

SCIENCE AND RELIGION

Bibliography

Acikgenc, Alparslan. Islamic Science: Towards a Defini-

tion. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: International Institute

of Islamic Thought and Civilization, 1996.

Al-Afghani, Jamal-al-Din. “Refutation of the Materialists.”

In An Islamic Response to Imperialism, Political and

Religious Writings of Sayyid Jamâl-al-Dîn al-Afghânî,

ed. and trans. Nikki R. Keddie. Berkeley: University

of California Press, 1982.

al-Attas, Seyd Muhammed Naquib. Prelegomena to the

Metaphysics of Islam: An Exposition of the Funda-

mental Elements of the Worldview of Islam. Kuala

Lumpur, Malaysia: International Institute of Islamic

Thought and Civilization, 1995.

Al-Faruqi, Isma’il Raji, ed. Islamization of Knowledge:

General Principles and Work Plan. Washington, D.C.:

International Institute of Islamic Thought, 1982.

Al-Ghaz1l3, Ab5 H1mid. Al-Munqidh min a#-Dal1l (Free-

dom and fulfillment), trans. and ed. R. McCarthy.

Boston: Twayne, 1980.

Arkoun Mohammed. “Le Concept de Raison Islamique.” In

Pour une Critique de la Raison Islamique. Paris:

Maisonneuve et Larose, 1984.

Bakar, Osman. Tawhid and Science: Essays on the History

and Philosophy of Islamic Science. Kuala Lumpur,

Malaysia: Secretariat for Islamic Philosophy and Sci-

ence, 1991.

Bucaille, Maurice. La Bible, le Coran, et la Science: Les

Écritures Saintes Examinées à la Lumière des Con-

naissances Modernes. Paris: Seghers, 1976. Available

in English as The Bible, the Qur’an, and Science: The

Holy Scripture Examined in the Light of Modern Sci-

ence, trans. Alastair D. Pannell and the author. Indi-

anapolis, Ind.: American Trust, 1979.

Butt, Nasim. Science and Muslim Societies. London: Grey

Seal, 1991.

Guénon, René. Le Règne de la Quantité et les Signes des

Temps. Paris: Gallimard, 1945. Available in English as

The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times,

trans. Lord Northbourne. London and Baltimore, Md.:

Penguin, 1953.

Hoodbhoy, Pervez. Islam and Science: Religious Ortho-

doxy and the Battle for Rationality. London: Zed

Books, 1991.

Hourani, Albert. Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age:

1798–1939. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press, 1983.

Ibn Rushd (Averroës). On the Harmony of Religion and

Philosophy (Kit1b Fas’l al-Maq1l wa Taqr3r m1 bayna

ash-Shar3hah wa al-Hikmah min al-Itti’1l), ed. and

trans. George Hourani. London, Luzac, 1976.

Lewis, Bernard. The Muslim Discovery of Europe. New

York: Norton, 1982.

Modh Nor Wan Daud, Wan. The Concept of Knowledge is

Islam. London: Mansell, 1989.

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. Science and Civilization in Islam,

2nd edition. Cambridge, UK: Islamic Texts Society,

1987.

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. The Need for a Sacred Science. Al-

bany: State University of New York Press, 1993.

Salam, Mohammed Abdus. Ideals and Realities: Selected

Essays of Abdus Salam, ed. C. H. Lai. Singapore:

World Scientific, 1987.

Sardar, Ziauddin. Explorations in Islamic Science. London:

Mansell, 1989.

Sardar, Ziauddin. Islamic Futures: The Shape of Ideas to

Come. London: Mansell, 1985.

Sardar, Ziauddin, ed. An Early Crescent: The Future of

Knowledge and the Environment in Islam. London:

Mansell, 1989.

Stenberg, Leif. The Islamization of Science: Four Muslim

Positions Developing an Islamic Modernity. Lund,

Sweden: Lunds universitet, 1996.

BRUNO GUIDERDONI

ISLAM,HISTORY OF SCIENCE

AND

RELIGION

An account of science and religion in Islam must

examine the attitudes of the faith of Islam towards

science, as well as the scientific enterprise in Is-

lamic civilization. The first aspect assumes that the

perspective of religious thinkers and religious in-

stitutions play a determinative role in science

through their coercive power or influential author-

ity. The second aspect tempers and even chal-

lenges this assumption, for it investigates actual

factors that facilitate or hinder scientific practice

LetterI.qxd 3/18/03 1:06 PM Page 469

ISLAM,HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND RELIGION

— 470—

during particular historical periods and examines

how and why particular social and political con-

texts promote or inhibit science.

These two aspects illustrate the complexity

surrounding the term Islam. Primarily, Islam de-

notes a faith with particular beliefs, practices, and

institutions within its historical and contemporary

diversity of expressions. Beyond faith, Islam de-

notes an empire and then a series of successor

states during particular periods in world history

over a vast expanse of territory in Asia, Africa, and

Europe. Despite inherent differences, these regions

shared the bond of participating in Islamic civiliza-

tion, although many inhabitants, including practi-

tioners of science, were not Muslims. The flow of

goods, ideas, fashions, and movements of peoples

through these regions and the common strands in

their intellectual, political, aesthetic, and social out-

looks and the social institutions of their elite

classes, broadly speaking, characterize these re-

gions with those particular features that are the

hallmarks of Islamic civilization. The account of

the relationship of science to the faith of Islam at

particular locales and times must acknowledge the

unifying role played by this civilization. On the

other hand, discourse regarding the relationship

between religion and science in contemporary

Islam is largely dominated by the notion that sci-

ence, albeit a universal human endeavor, is never-

theless largely developed and exported from ex-

ternal sources, namely the Western world.

Faith to civilization

The faith of Islam was established in seventh cen-

tury

C.E. by the Prophet Muhammad (570-632 C.E.),

who, according to Muslim belief, was the recipient

of divine revelations, which are collected in the

Qurhan, the Muslim sacred text. Facing hostility and

opposition, Muhammad fled his birthplace of

Mecca, in present-day Saudi Arabia, to Medina. By

the end of his life in 632

C.E., he overcame oppo-

sition and united almost the entire Arabian penin-

sula under the banner of Islam. Muhammad had

commanded both religious and political authority,

and his death raised the issue of the scope and

manner of the subsequent exercise of authority.

Not surprisingly, there were, and continue to be, a

range of responses. Over the centuries, these re-

sponses solidified into religious and political insti-

tutions, as well as a multiplicity of attitudes re-

garding their power and authority. Although

sectarianism played a role in shaping some atti-

tudes, the lack of a centralized religious institution

fostered a diversity of attitudes on all subjects, in-

cluding the relationship of religion to science.

The nascent community established the prima-

rily political institution of the caliphate following

the death of Muhammad. Disagreement between

supporters of iAl3 (d. 661 C.E.) and his opponents

over succession and the scope of this office was to

later crystallize into the Sh3i3 and Sunn3 branches of

Islam. Over the next three decades, under the lead-

ership of companions of Muhammad, the commu-

nity commenced a campaign of expansion

whereby Palestine, Syria, Egypt, and Iran were

soon incorporated into the emerging Islamic em-

pire. These “rightly-guided” caliphs were suc-

ceeded by the Umayyads (661–750

C.E.), who con-

tinued the expansionist policy. The Umayyads

faced several rebellions because of their perceived

Arabo-centrism. They also resisted the efforts of

religious elites to establish normative frameworks

for religious study and institutionalization of reli-

gious authority. Since this venture was external to,

and at times actively opposed by, the Umayyad

court, the genesis of a recurrent conflict between

religious and political authorities in Islamic polity

was born.

By the early eighth century, the Islamic empire

reached its greatest expanse, extending from Spain

to the Indus and the borders of China, thereby in-

corporating Hellenistic and Iranian centers of sci-

ence, philosophy, and learning. Like its predeces-

sors, this vast empire, with its diversity of peoples,

languages, faiths, traditions, and administrative and

monetary systems, was susceptible to divisive

forces. iAbd al-M1lik (r. 692–705

C.E.) therefore

sought to unify the empire by instituting Arabic

coinage and the Arabic language as the adminis-

trative language of the empire. Arabic was soon

catapulted beyond the language of revelation and

then language of governance to the language of lit-

erature, humanities, philosophy, science, and in-

deed all learned discourse. The attitude towards

science at the Umayyad court was utilitarian. Evi-

dence suggests that the court sought physicians

who were primarily non-Arab and non-Muslim.

In 750 C.E, the Umayyads were overthrown

and replaced by the Abbasids everywhere but in

Spain. Even though they had capitalized on the

anti-Umayyad sentiment of the religious elite, the

LetterI.qxd 3/18/03 1:06 PM Page 470

ISLAM,HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND RELIGION

— 471—

Abbasids soon distanced themselves from their for-

mer allies. The litterateur Ibn al-Muqaffai(d. 757

C.E.) advised the Abbasid Caliph al-Man’5r (r.

754–775

C.E.) to bring the religious elite under state

supervision and to enforce doctrinal and legal uni-

formity to replace diverse and opposing views.

Even though this advice was ignored, the episode

illustrates the continuing fluidity of political and

religious institutions.

The Abbasids consciously promoted a new

order. This was most evident in their establishment

of the city of Baghdad in 762

C.E. in present-day

Iraq. Baghdad soon became a thriving commercial

center and magnet. Above all, it represented the

civilization of Islam with its own distinctive literary

and aesthetic preferences, attitudes, institutions,

and fashion of refinement. The Arabo-centrism of

the early Umayyads was replaced by a bustling en-

gagement of peoples of many faiths and persua-

sions from all parts of the empire. The splendor

and richness of the early Abbasid period, under the

reign of the Caliph H1run al-Rash3d (r. 786-809

C.E.), was later immortalized in the Thousand and

One Nights. But this prosperity came at a price, as

the Caliph was forced to grant fiefs to commanders

and strongmen. The fiefs soon became semi-inde-

pendent principalities, leading to the disintegration

of the unified empire by the mid-ninth century.

Nevertheless, the vision of a unified Islamic civi-

lization endured for several centuries in a number

of successor and competing principalities, thriving

in even small provincial centers, as well as still-

Umayyad Spain.

The “sciences of the Ancients” and religious

sciences of Islamic civilization

In his Introduction to History, the fourteenth-cen-

tury historian Ibn Khald5n (1332-1382 C.E.) notes

that urban civilization is characterized by sciences

and crafts:“. . . as long as sedentary civilization is

incomplete . . . people are concerned only with

the necessities of life. . . . The crafts and sciences

are the result of man’s ability to think . . . (they)

come after the necessities” (p. 2:347). Ibn Khald5n

includes agriculture, architecture, book produc-

tion, and medicine among crafts of urban civiliza-

tion. With regards to the sciences: “one [kind] . . .

is natural to man . . . guided by his own ability to

think, and a traditional kind that he learns from

those who invented it” (p. 2:436). The first kind are

the “philosophical sciences”; the second, the “tra-

ditional, conventional sciences.” Such a distinction

was already recognized by Muhammad al-

Khw1rizm3 (d. 997

C.E.) in the tenth century. He di-

vided the sciences into “sciences originating from

foreigners such as the Greeks and other nations”

and “the sciences of the Islamic religious law and

ancillary Arabic sciences.” Al-Khw1rizm3 under-

stood that these attributes denoted origins and

were not judgments of intrinsic worth. The reli-

gious and Arabic language disciplines were pecu-

liar to Muslims, originating after the advent of

Islam; science and philosophy originated in pre-

Islamic civilizations and were appropriated into Is-

lamic civilization. Within Islamic civilization, the

religious and Arabic language disciplines preceded

the appropriation of the “sciences of the Ancients,”

but the mature development of both was largely

coterminous.

The disciplines of philosophical theology

(kal1m) and Islamic law ( fiqh, shar3ha) are para-

mount to an account of the relationship between

religion and science in Islam. By the late eighth

century, Muitazil3 philosophical theology was im-

mersed in cosmological questions, primarily, cre-

ation ex nihilo (from nothing), the fundamental

constituents of the world, the nature of man, and

God’s causal role in the world. Notwithstanding a

plethora of views in the early period, the late ninth-

century consensus held that the world was created

ex nihilo; its material, temporal, and spatial struc-

ture is atomistic; human beings are complex com-

positions of such atoms (i.e., material beings); and

God, who is completely different from created be-

ings, is the primary causal agent, although for the

Muitazil3s,human beings have a limited causal role

(the dissenting Ashiar3 view denied human causal

agency). These positions are directly opposed to

the Aristotelian bent of the “philosophical” sciences.

Reason played a primary role in the epistemol-

ogy of the Muitazil3 philosophical theologians. Rea-

son also played a role in early Islamic legal theory.

The primacy of reason was attacked by conserva-

tive religious scholars, who instead upheld the pri-

macy of revelation and the inspired example of

the Prophet Muhammad’s personal practice

(sunna). These sources, in conjunction with the

consensus of the religious elite (ijm1i) narrowly

confined to the two sources of revelation and

Muhammad’s practice, provided, in their view, the

“Islamic” basis for all spheres of human activity.

LetterI.qxd 3/18/03 1:06 PM Page 471