Wakeman Rosemary. The Heroic City: Paris, 1945-1958

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

246 | chapter six

Saint-Germain-des-Prés

Despite the noisy youthful effervescence that spilled into its streets, Saint-

Germain-des-Prés retained its enigmatic intellectual quality in the 1940s. The

avant-garde had already migrated from Montparnasse and taken up residence

in its cafés in the years before the war. In 1939, Léon-Paul Fargue described

the place Saint-Germain-des-Prés, with its ancient abbey church, as one of

those places in the capital where you felt the most “up-to-date, nearest to

current trends and the men who have their finger on the pulse of the country,

the world, Art.” For Fargue, “the place lives, breathes, throbs, and sleeps by

virtue of the three cafés more famous today than the institutions of state: the

Deux Magots, the Café de Flore, and the Brasserie Lipp.”

8

It was in the Café

Flore and the Deux Magots that the beau monde of avant-gardism and left-

wing intellectual culture—Marcel Carné and Jacques Prévert, André Breton

and Pablo Picasso, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir—shared tables

and conversation. The Brasserie Lipp on the opposite side of the boulevard

Saint-Germain-des-Prés was the nerve center of right-wing intellectuals. They

even co-opted the Left Bank name in their Rive Gauche lecture group, which

met at first in the Vieux-Colombier Theater and later at the Bonaparte Cin-

ema on the place Saint-Sulpice, or they met at the Rive Gauche bookstore on

the boulevard Saint-Michel. The rival factions generally inhabited the same

Left Bank space, just as they shared the same publishers—Gallimard and

Grasset. In general, the Left Bank suffered fewer of the injustices inflicted

by the occupation on other areas of the city. The district was cheerless and

deserted, the food markets bare. The cafés remained open with the usual

clientele, now escaping flats made frigid by the fuel shortage. Life went on.

The Germans never set foot in the command center of left-wing intellec-

tual life, the Café de Flore.

9

Most of the avant-garde who remained in Paris

chose either to keep their heads down and continue working, or to negotiate

with the regime in a way that avoided moral abrogation. But the superficial

security of the district hid the troubled road of Parisian intellectuals to either

collaboration or resistance.

It was the intimate parish quality, the cheap flats and bistros, of Saint-

Germain-des-Prés that made it a cultural scene on the frontier between the

bourgeois capital of the Right Bank and the old literary and art colonies of

Montparnasse. The district was nostalgically portrayed by poets, novelists,

and sentimentalists as a cherished quotidian village of working people, of

the left bank | 247

courtyards and craft shops clustered around its church. Some of the old elites

still clung to their mansions along the quiet streets. But even the most digni-

fied of the district’s buildings were showing their age, and the more mundane

structures were just shoddy and ramshackle. In the early postwar years Boris

Vian wrote a Manuel de Saint-Germain-des-Prés and drew the perimeters of the

island, “with its insular nature,” that was taking shape as a youthful mecca:

from the quai Malaquais and the quai Conti down the rue Dauphine to the

rue de l’Ancienne-Comédie and then to the rue Saint-Sulpice, the rue du

Vieux-Colombier, and the rue des Saints-Pères.

10

Cheap and ordinary, the

district’s socially heterogeneous quality and idiosyncrasy by comparison to

the glitter on the Right Bank gave it an air of refuge, freedom, and avant-garde

chic. The beau monde of would-be intellectuals shared the public spaces and

bistros with vagrants and the poor, with North Africans looking for work,

with a working-class subculture simply going about its daily life. In other

words, they settled into precisely the populist world that French sociologists

and urbanists were so intent on discovering.

It might have been a bohemian hangout, but there was little to suggest

that Saint-Germain would become a zone of musical novelty. It was the

cabarets of the Right Bank, such as Chez Agnès Capri on the rue Molière

and Chez Gilles on the avenue de l’Opéra, and the celebrated theaters and

musical halls on the grands boulevards that captured the imagination of musical

devotees, even during the occupation. But the early postwar years brought

a fracturing in the city’s cultural geography. The music and entertainment

scene shifted toward the Left Bank, where an avant-garde of young enter-

tainers was introducing new musical forms. They performed on the Right

Bank only after they became famous. Immediately after the Liberation, Henri

Leduc, the flamboyant impresario of Montmartre and Saint-Germain-des-

Prés, opened Le Bar Vert on the rue Jacob, the first cabaret to play American

music. Claude Luter and his jazz combo set up the first basement club in

the Hôtel de Lorient in May 1946 on the rue des Carmes. The basement

boîtes and sidewalks of Saint-Germain-des-Prés pulsated with the sounds of a

growing revelry of jazz musicians and devotees. The basement clubs formed

an underground spatial realm. Music was appropriated as the voice of a new

generation and its transgressive, antiestablishment urban order. The clubs

competed for the favors of American jazz greats. When Duke Ellington played

the Club Saint-Germain-des-Prés in 1948, more than a thousand admirers

jammed into the narrow rue Saint-Benoît to catch a glimpse of their idol.

248 | chapter six

Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis followed. The Vieux-Colombier countered

with Sidney Bechet. For the writer Olivier Merlin, their horns trumpeted the

“pure spirit of Paris.”

11

The French acceptance of American cultural forms

was certainly problematic, and would become more so as the cold war and

the 1950s advanced. But it was clear that the young people emerging from

the shadow of war were fascinated by American music, American film, and

American popular culture.

At the same time, in clubs such as La Rose Rouge, Le Quod Libet, and

L’Échelle de Jacob,

12

the entertainers Boris Vian, Francis Lemarque, and

Juliette Gréco (the darling of the existentialists) created their own style of

poetic, spoken Left Bank music. One Parisian, Anne-Marie Deschodt, re-

membered that her musical education had been “honorable” up to 1947,

when she “became old enough to go out alone,” left behind the Edith Piaf

records in her family’s apartment, and headed for a jazz festival in the streets

of Saint-Germain-de-Prés to hear Vian, Jacqueline François, and Gilbert

Bécaud.

13

The district’s avant-garde soundscape was disruptive and rebel-

lious. The vocal group Frères Jacques was a good example of the innovative

musical combinations of jazz, French yé-yé, and early rock ’n’ roll emanating

from the Left Bank during the post-Liberation years. The group’s originator,

André Bellec, participated in both the Vichy regime’s wartime Chantiers de

jeunesse (youth work camps) and the postwar Travail et culture movement

(TEC). The four “brothers” of Frères Jacques mixed song, humor, dance,

and mime in a colossally successful cabaret act that was both folkloric and

novel in content. The Frères Jacques were the headliners at La Rose Rouge

and emblematic of the club’s reputation as a laboratory of musical experi-

mentation. There the poetry of Jacques Prévert, the music of Joseph Kosma,

and the verse of Raymond Queneau and François Mauriac sung by Juliette

Gréco, Léo Ferré, and the Frères Jacques captivated their audiences. The

genre functioned as a paradigmatic resource, a medium for the constitution

of an alternative youth identity and engagement. The nightclub became the

emblematic social space, the training ground in which the parameters of

youthful rebellion could be tested. They were a place of bricolage, of impro-

visation, and of seditious performance.

Prévert’s populist language and lyrical style, the open defiance of his Pa-

roles and its humor, matched the libertarian mood of young men and women,

the zazous and students emerging from wartime captivity. His poetry was

the bebop or the boogie-woogie of the written word and existentialism for a

the left bank | 249

generation for whom the philosophy meant living to the fullest a life of per-

sonal freedom. Prévert had been a mainstay of the Saint-Germain scene since

before the war, where he lived (on the rue Dauphine), launched his Groupe

Octobre amateur acting troop, and began writing song lyrics. Prévert was

everywhere in Paris at the war’s end. In the spring of 1945 the singer Ger-

maine Montero gave a Prévert recital at the Athénée Theater accompanied

on the piano by Kosma. In June the ballet Le Rendez-vous, created by Roland

Petit and written by Prévert with music by Kosma, was staged at the Sarah

Bernhardt Theater. At the end of 1945 his play L’École buissonnière was staged

in Paris, and five radio programs hosted by Robert Scipion were devoted to

Prévert and his opus. In 1946 four films for which Prévert had written the

screenplay—Aubervilliers, Les Enfants du paradis, Sortilèges, and Le Voleur de

paratonnerres—were in movie houses at the same time a recital of Prévert and

Kosma’s music was being given at the Pleyel Theater. In her autobiography

The Prime of Life, Simone de Beauvoir described the extraordinary position

held by Prévert among the artistic elite gathered at Saint-Germain-des-Prés

and the Café de Flore: “At the time, their god, oracle and mentor was Jacques

Prévert, whose films and poems they worshiped, whose language and wit

they sought to emulate.”

14

By 1954 the periodical Positif published an edito-

rial acknowledging that “the real world is beginning to look a lot like that

imagined by Prévert.” Claude Roy acknowledged that

everywhere in Paris it seems we find Prévert. Just as of a landscape, we

say “It’s a Corot,” or of a street corner on Montmartre, we say “It’s an

Utrillo,” we find Prévert in a conversation on the street, in the smile of

a flower-vendor, or a taxi driver’s belting out his songs. He is with us in

his films, his poetry, his music, the long monologues he weaves about

life and everyone’s passing days.

15

The singer and songwriter Francis Lemarque also personified this politi-

cally engaged French style of music and spoken word that sprang from the

spaces of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. His performances headlined on the cabaret

circuit at La Rose Rouge and L’Échelle de Jacob, while his plays were staged

at the neighboring Théâtre de l’Humour and the Théâtre de Poche. Lemarque

traveled in Prévert’s charmed circle in Saint-Germain-des-Prés and through

him met Yves Montand, who commissioned a multitude of his Paris ballads.

Many of Lemarque’s songs evoked the working-class neighborhoods of Paris,

250 | chapter six

the world of guinguettes, bals musettes, and young bands of teenage hoodlums.

Although he never became a Communist Party member, his work was com-

mitted to the Left and the avant-garde pacifism that dominated the Left Bank

milieu. Lemarque performed regularly at Communist Party galas and youth

festivals. In the mid-1950s he embarked on a series of major international

tours to communist countries, from China and the Soviet Union to North

Korea. His anti-war classic “Quand un soldat” rocketed to fame in 1953:

“When a soldier leaves for war / With a shiny weapon in his pack/ . . . Leaving

perhaps to die / To war to war / It’s a strange little game / That no one loves

/ But always / When summer arrives / They go . . . those who will die.” When

the Soviets launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957, Lemarque immediately

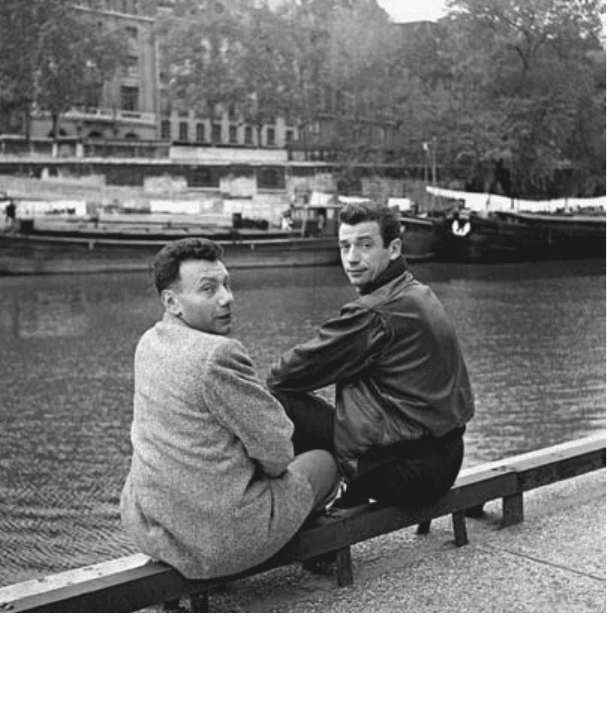

figure 27. Francis Lemarque and Yves Montand along the Seine, September 30, 1953.

© gerald bloncourt/rue des archives.

the left bank | 251

celebrated this coup de grâce against the United States with “Soleil d’acier”

(Lemarque and Castella, 1957): “A flaming sun of steel / Passes over and

wakes me / It rises in the sky to explore the universe.”

16

His performances at

the legendary Olympia in 1958 with Paul Anka as the headliner were among

the high points of a long and successful career as one of the most Parisian

singer-songwriters to emerge from the Saint-Germain-des-Prés scene.

La Rose Rouge was only one in a circuit of nighttime haunts on the streets

of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Each cultivated its own brand of entertainment

and stars, its own enthralled groupies, its own rituals. Music was used as a

form of spatial mapping. The battle raged between the clubs that remained

loyal to traditional jazz and those, such as the Tabou and the Caveau de la

Huchette, that became “bebop havens,” with boogie-woogie and jitterbug

dance exhibitions that spilled out into the street.

17

Police were called in to

intervene regularly throughout the 1950s when the jam sessions, concerts,

and party scenes on the place Saint-Germain-des-Prés got out of hand. There

was a spontaneity and libertarianism to these performances that combined a

carnival formula with youthful transgression. It had its own cultural pastiche.

The lettrist Gabriel Pomerand recited “letter poetry” in the middle of the

night at the Tabou. The strategy of provocation, of undercutting accepted

norms, was applied to raffish cabaret skits and beauty contests immersed

in sexual play and innuendo. The Miss Tabou and Miss Vice contests were

amateur strip teases, while the election of Apollo at the Tabou was the oc-

casion for young men in briefs to show off their muscles. In Mythologies,

Roland Barthes remarked on the spectacle and erotic power of these noto-

rious amateur striptease contests, noting that their very awkwardness gave

them unexpected sensual and seditious qualities.

18

Chicago night required

gangster costumes, while western night meant women in saloon-girl getups.

They were a form of mockery, of confrontational charade. The rest of Paris

saw these youthful agitators as bent on outrageous, vulgar farce. They excited

a mixture of scandal and envy. Le Tout-Paris arrived to imbibe the depraved

ambience and pose for the paparazzi.

Although the clubs inevitably took up residence in some long-forgotten

cellar, the cafés, streets, and public spaces of Saint-Germain-des-Prés them-

selves became emblematic of the new youth culture. The Café de Flore, the

Deux Magots, and the Brasserie Lipp formed a golden triangle of existential

cool and sophistication. The Chop Gauloise on the rue Bonaparte and Chez

Georges on the rue des Canettes were cheaper alternatives that were still

252 | chapter six

within sight of the glitterati. For hip young people reaching adulthood in the

reconstruction years, existentialism meant an unrestrained freedom from the

black years and a new confidence in the future, despite difficult times and

hard choices. They searched for self-awareness and intensity of experience.

Existentialism was a form of philosophical and personal rebellion. It was a

seizing of intellectualism, a dramatic transfusion of the public sphere. As a

radically new system of values, it was practiced as a lifestyle, an image-act,

an “offensive,” to use Simone de Beauvoir’s term, in a spatial theater car-

ried out in the streets, cafés, and nightclubs of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. The

movement was instrumental to the way the Left Bank was produced, and it

revolutionized the city on behalf of a new postwar generation. Its followers

were legion. The city’s avant-garde elites, from Camus and Merleau-Ponty

to Gréco and Vian, were held in its sway.

The district was also the haunt of American tourists and modish young

expatriates anxious to brush up against la vie de bohème and the avant-garde

scene.

19

Joining them was a new generation of American black and Latin

American writers, artists, and musicians. Richard Wright and James Baldwin

moved with ease in the world of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Jorge Amado en-

joyed the charmed friendship of Sartre and de Beauvoir. The bistros presided

over by the literati, the experimental film festivals and theater premiers, the

dance parties and soirées, the avant-garde publications and esoteric magazines

found in trendy bookstores, functioned as an exhilarating form of spatial the-

ater. It was the heyday of the film clubs in Paris. Students and young people

gathered at the Ciné-Club d’Avant-Garde, the communist Ciné-Clartés

at the Lux-Rennes, and the Ciné-Club du Quartier Latin to see the latest

films or experimental œuvre. This last was the hang-out of Jean-Luc Godard,

Eric Rohmer, and François Truffaut. It was at the Ciné-Club du Quartier

Latin that Guy Debord’s Hurlements en faveur de Sade was first previewed

in 1952. The tiny Théâtre de Poche, the Vieux-Colombier, the Huchette,

and the Noctambules mounted bare-bones improvisational productions.

The bookstores on the rue de l’Odéon were hip meeting grounds for read-

ings and discussion. The new La Hune bookshop alongside the Café Deux

Magots launched avant-garde exhibitions. The most prestigious publishing

houses were within a stone’s through of the abbey church; Gallimard, Le

Seuil, Émile-Paul, and Flammarion were among the most important of these.

Sartre’s Les Temps modernes and Emmanuel Mounier’s Esprit both had their

offices in the neighborhood. These revues were as much literary-political

the left bank | 253

movements as businesses, and their weekly staff meetings were opportunities

for passionate debate. Every word of muscular left-wing publications from

Combat and Les Lettres françaises to Les Temps modernes was poured over and

discussed endlessly. Every move by Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir in their

Saint-Germain-des-Prés haunts was avidly scrutinized in the press. They

became celebrities in a mythic public theater carried on daily in which any

number of disciples could take part.

Sensationalist newspapers such as Samedi-soir and France-dimanche pub-

lished lurid accounts of the district’s night spots and its would-be existential-

ists. In May 1947 Samedi-soir catapulted Saint-Germain-des-Prés into the

spotlight with a front-page photo of the “existentialists” Roger Vadim and

Juliette Gréco (in tight slacks) in a basement club. The photo was accompa-

nied by the instantly taken-up catch phrase “This is how the troglodytes of

Saint-Germain-des-Prés live.” “It is in their basement refuges,” the in-depth

scoop began, “that existentialists waiting for the atomic bomb drink, dance,

love, and sleep.” In September 1951 Les Actualités françaises ran a televised

news report titled “L’existentialisme à Saint-Germain-des-Prés” that featured

the complete symbolic panorama.

20

The camera pans the great open square

shared by the abbey church, the Deux Magots, and the Café de Flore, where

a young American couple on their honeymoon takes in the sights. Throngs

of young people mill around the bistros. Juliette Gréco strolls nonchalantly

past the outdoor tables, which are packed with gawkers. Jean-Paul Sartre is

spied at the late-night jazz scene at the Club Saint-Germain-des-Prés. The

film is filled with young zazous turned existentialists in beatnik black with

their scooters and broken-down Renaults, promenading the streets and con-

gregating in the cafés, meandering through the bookstores and neighborhood

groceries, and above all in the basement jazz clubs. Young couples jam the

dance floors showing off their wildest jitterbug and bebop acrobatics while

others line the walls puffing on cigarettes, drinking, and swinging to the music.

Sunglasses, bare feet or sandals, and svelte black signify these hip, cerebral

trendsetters. “Ah,” the film commentator ends, “and so this is existential-

ism!” The repetitive, stereotypic quality of these mediatized images speaks

to their role as a visual code for the unconventional and for understanding

the new, liberated postwar world.

The director Jacques Becker captured this new Paris in the 1949 film

Rendez-vous de juillet, which was an immediate sensation and also won the

film critics’ Prix Louis Delluc. The subject was the “unknown zone” of the

254 | chapter six

“unknown” young generation,

21

the J3s growing up during the war and its

aftermath. In an almost photojournalistic montage, we follow the adventures

through Paris of a troop of friends, played by unknown actors starring in

their first film. The sequence of scenes shoots back and forth between their

individual stories. The characters traverse the film and the public spaces of the

city. The effect was the creation of a public domain of simultaneity, vitality,

and mobility. The young Parisians glide down the Seine in a used American

amphibious vehicle driven by their zazou buddy. They haunt the Café Lori-

entais and descend into the basement clubs of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. The

jazz of Claude Luter is their religion. They attend classes on the Left Bank

and act in its theaters. At night they stroll through the streets on their way

to dance parties. They smoke American cigarettes and talk on the telephone

endlessly, to the chagrin of their bourgeois and petit-bourgeois parents, who

press them to get “real jobs.” But life is good; the future beckons. They follow

their own ambitions. Roger plays trumpet in a jazz combo and dreams of

owning a movie theater, while Thérèse pursues an acting career in an avant-

garde drama. Lucien studies ethnography at the Musée de l’Homme and

tenaciously searches for funding to become an explorer in Africa. When his

friends cave in to family pressures, he castigates them for not “following their

dreams.” But these individual stories are not as important as the visualiza-

tion of the Left Bank itself. In a review in Combat, Jacques Chastel argued

that the Paris of Rendez-vous de juillet “is the first Paris in the cinema that

actually resembles that of Parisians” in the exactitude of its presentation of

daily life and behaviors.

22

The motif is material well-being and the modern,

hip universe of early postwar Paris. These young people are the hope for a

better society. There are archetypes of the future. Despite obstacles, despite

the typical calamities of adolescence they face, Becker’s film is explicitly

optimistic about their prospects. They move through the streets and public

spaces of the city with confidence and aplomb. In this urban choreography,

they pass from the war and its disillusion to fantasies about the future and

thence to the tangible realities of ambition and experience.

This mental image of postwar Paris has become so familiar that it is easy

to forget how transgressive and nonconformist this youthful street theater

was. The free-spirited unruly style was an affront to the “return to order,”

the straitlaced, moralizing sensibilities of reconstruction. In his memoir Paris

after the Liberation, the British historian Antony Beevor remarks that the tight-

fitting black sweaters and slacks of Saint-Germain’s young women provoked

the left bank | 255

shock and acrimony in the beaux quartiers of Paris: “On the Right Bank, a girl

wearing trousers risked having things thrown at her.”

23

The dancing, music,

and indigent lifestyles were associated with moral corruption and unbridled

sexuality. Sex and the social in Saint-Germain-des-Prés were signs of warping

and deviance, of subversion. However, what the troglodytes had was pastiche

and free play. Part fascinating, part shocking, the performance landscape of

Saint-Germain-des-Prés contributed to the image of youth as deviant, ex-

otic, celebratory, and entertaining. It was antiestablishment. Vian captured

the sense of burlesque political theater in “La Java des bombes atomiques,”

written after the March 1954 explosion of the first American H-bomb on

Bikini Island and recorded by the French singer and actor Serge Reggiani.

A member of the Resistance, Reggiani returned to Paris at the war’s end and

starred in his first feature film, Les Portes de la nuit, as Malou’s brother; His

bad-boy image made him all the rage among young music enthusiasts.

My uncle, a well-known handyman

Made on his own

Some atomic bombs

. . . Making an “A” bomb

. . . Is like making a tart

The question of the detonator

Amounts to a quarter of an hour

. . . As to the “H” bomb

There’s no big difference

. . . Knowing the results are the same

All the heads of state

Came to visit him

. . . And, when the bomb exploded

Of all these personages

Nothing remained

The vulgar antics and buffoonery of improvisational theater in the cabarets

and the cafés had the quality of resistance and release, the sense of alterna-

tive realities. Saint-Germain-des-Prés was a space of bricolage: a cheerful

and cheeky cobbling together, an expressive assemblage of bits and pieces

that mocked the traditional urban realm. The result was carnivalesque, ka-

leidoscopic, and ultimately subversive. The celebratory, slapdash practices