Wakeman Rosemary. The Heroic City: Paris, 1945-1958

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

226 | chapter five

its own stereotype and exaggerating community cohesion. In La Butte à la

Reine, the production team of Bergeret, Krier, and Chombart began by ad-

mitting that the term “solidarity” had been overused and was not meant to

discount the hardship in slums like Moulin de la Pointe. Nevertheless, they

emphasized that “human warmth” existed in working-class neighborhoods

despite their obscurity and appalling difficulties. Fraternity and solidarity

were lived experiences.

39

The tone was emotional, poignant, and expressive

of a collective dimension that stood outside material conditions. Urban space

was a trope for overheated humanistic ambitions.

Popular films, documentaries, and television programs did not impose a

single overarching vision. But we can say that the humanist perspective played

a significant part in how the public sphere was identified and produced and in

imagining what took place in the spaces that accompanied it. A set of visual

codes and characteristic sites was invented by film and television to stand for

this intensely lyrical humanist idiom. Regardless of the visual genre, urban

space is depicted with the same conscious consistency. Paris was a visual set-

ting saturated with emotional, psychological, and social meaning. The films

were exquisite tales of urban struggle that were based on a postwar socioeth-

nographic perspective that professed to understand the French as they really

were. Neither the silver nor the television screen presented unnerving scenes

of the street protests or the rioting, strikes, and crisis of decolonization taking

place in the streets of Paris. Even the production of destitution and urban

squalor retained a fantastic and fatalistic quality. The peuple suffered in these

films, but they patiently endured and remained faithful to French values.

Portraits in Film Noir

Paris may have been an alchemical mix of power and possibilities, but the

irony of these years is that it was also a place of disillusion and false hope that

was best captured in so-called film noir or noir realism. These crime thrillers,

detective stories, policier, and polar used stark lighting, unusual angles, and

black-and-white composition to create a dark urban realm. Their subject

matter was a somber social realism, violence and loss, and ambivalence about

the moral universe. The protagonists realize too late that they are victims of

fate and of the roles they have chosen.

40

Marcel Carné’s 1946 production

Les Portes de la nuit is one of the great icons of this genre.

41

It was also filmed

entirely in the studio. The clarity of Carné’s vision was, of course, already

paris as cinematic space | 227

well-known. He was the master portraitist of Paris populaire in the forgotten

corners of the city, away from the monumental capital. The son of a furniture

maker in the faubourg Saint-Antoine, Carné was orphaned and raised by an

indulgent grandmother in the Batignolles district of the 17th arrondissement.

His personal image of the city’s poor industrial neighborhoods garnered

popular acclaim in the 1930s with masterpieces such as Hôtel du Nord (the

canal Saint-Martin), Jenny (the canal de l’Ourcq), and Le Jour se lève (the

working-class faubourgs). It was also Carné’s film depictions that produced

the most influential and popular imagery of “the people” that reemerged

during the Liberation and euphoric years that followed. They were marked

by the tension between a gritty realism and a romanticized metaphysical

dimension beyond that represented on the screen. Carné’s style of populist

realism made everyday people into heroes, often of the tragic kind. They were

embodied by the actors Jean Gabin and Yves Montand. Everything about

their screen personas labeled them as typical working-class Parisians, a social

type identified by gestures, language, clothes, and milieu. Carné sketched

their portraits, while the screenwriter Jacques Prévert gave them voice. It was

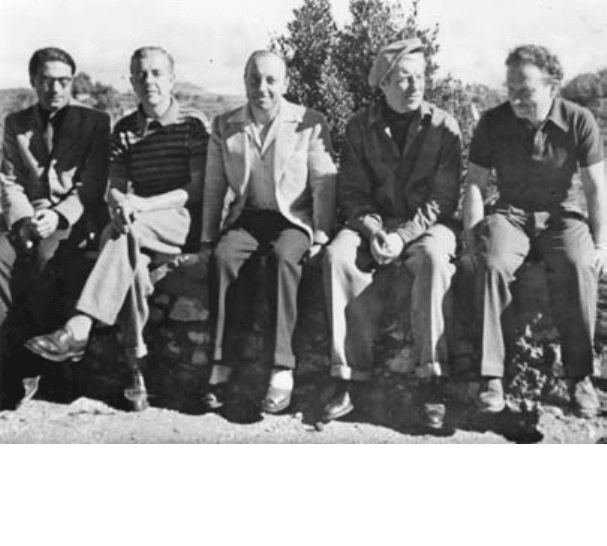

figure 24. Joseph Kosma, Jacques Prévert, Marcel Carné, Jean Gabin, and Alexandre

Trauner. © cinemathque franaise.

228 | chapter five

a team that emerged from the communist and surrealist avant-garde move-

ments of the 1930s and was committed to fashioning working-class art and

a more humanist future. Their vision of the working classes was lyrical and

metaphysical, yet set on the surfaces of the city in the concrete social milieu

of the city’s industrial neighborhoods. The people of Paris were indivisible

from their spatial environment. Even in tragedy, Paris was magical. Its ap-

peal was irresistible. The portrayal was closest to that of Zola in its dramatic

naturalism and depiction of the urban landscape. According to Carné, “The

star of Les Portes de la nuit would be neither a Marlene [Dietrich] nor a Gabin,

but a working-class neighborhood in the capital during the sad winter that

followed the magnificent summer of the Liberation.”

42

The film was an urban adaptation of Prévert’s ballet Le Rendez-vous and

a deliberate revival of the poetic realism that had been banned during the

occupation and that now served the emotional rapture and despair of the

postwar years so well. Once again, the team included set designer Alexandre

Trauner, composer Joseph Kosma, and cameraman Roger Hubert—all from

Les Enfants du paradis. But the circumstances had changed. Although Prévert

had played little role in the Resistance, he was deeply affected by the Libera-

tion and the subsequent purges. The publication of his first book, Paroles,

in 1946 met with immense popular acclaim, and he was ready to exert his

newfound status on the film team by merging the classic themes of tragic

love and heartbreak with the all-too-real tragedies found in the city’s spaces

just after the Liberation. The scene was Carné’s own Barbès-Rochechouart

Métro station near the gare du Nord and the Paris populaire of the 18th and

19th arrondissement. At a time when the Barbès station barely functioned,

precious resources (according to the critics) were used to construct Alex-

andre Trauner’s cinematic stage set, populated with a universe of Parisian

stereotypes constructed long before the war: street hawkers and paperboys,

vagabonds and locals, street singers and accordionists wandering amid com-

muters racing for the train. Carné and Prévert’s characters are controlled by a

hidden fatalism, and the itinerants who frequent the city embody this theme

of destiny. Jean Vilar plays the role of Fate, who is disguised as a tramp haunt-

ing the streets at Barbès-Rochechouart. His portrayal of the vagabond-seer

who watches the inevitable tragedy of the city’s life play itself out is one of the

most evocative superimpositions of cultural meaning on to the cityscape.

It is at the Barbès Métro station that the résistant and proletarian hero

Jean Diego—Yves Montand, in his first film—chances upon Fate, who fore-

paris as cinematic space | 229

tells that the young man will meet and fall in love with “the most beautiful

girl in the world.” The young Montand had met Prévert in Provence in 1948

and introduced the film’s title song, Autumn Leaves, with lyrics by Prévert

and music by Kosma, which immediately became a popular hit. Although

the film itself was a commercial flop, it served as a vehicle for Montand’s

stardom, thanks in good part to Kosma’s brilliant musical adaptation of

Prévert’s poetry. The visual quality of poetic realism was particularly arrest-

ing, but its musical and performance dimensions were just as essential to

its achievement and linked it to French theatrical tradition. Kosma himself

was one of the most influential forces in French popular culture, providing

the music to Prévert’s parole and writing a host of film scores that included

Le Crime de Monsieur Lange (1936), La Grande illusion (1937), Les Enfants du

paradis (1945), and even Le Chanois’s Sans laisser d’adresse (1951). He chose

to work with Prévert “to express man’s anguish before the menace of the

modern world, which seemed inhuman.”

43

This ethic marked his scores as

ideal for a film genre of romantic tragedy, melancholy, and regret.

In the film, Fate’s prophecy comes true, and Jean Diego meets Malou

(Nathalie Nattier), who has left an unhappy marriage and found her way

back to the working-class neighborhood where she was born and spent her

youth—“although,” she tells her war-profiteer husband, “it is too simple

for you.” Diego and Malou interact in a disturbing exposé of the city’s

postwar persona. The film laid bare the misery and tragedy of the northern

working-class districts between the Barbès station and Aubervilliers in the

autumn of 1945: the hunger and cold, the shortage of coal and electricity,

the squalid housing, the fiendish tone of the black market, the neighbor

accused of collaborating “at Drancy.” The interpretation of the industrial

landscape of warehouses, murky canals, and railroad yards is sinister and

forbidding. The city is shrouded in eternal night and populated by ruthless

scoundrels, femmes fatales, frauds, and traitors. Malou’s father was accused

by his neighbors of collaboration, and her brother worked for the Milice.

While they live in comfort, children steal wood for heat, and the destitute

scour through street garbage. An atmosphere of malaise and hideous cru-

elty permeates the gloom. Only Diego and his Resistance friends show any

humanity. Diego is a promethean image of the average working guy who

has stayed the moral course through the Black Years of the war. The film

exalts the sacrifices made by these ordinary people. Although Diego and

Malou inhabit a moribund landscape, they magically transform it into a

230 | chapter five

terrain of startling shape and beauty. A dreamy sexual desire pervades the

atmosphere. But tragedy awaits the young lovers. The doomed Malou is

shot by her dejected husband and dies in Diego’s arms. A bittersweet mel-

ancholy permeates the atmosphere in this sad depiction of the future after

the euphoria of the Liberation. The city’s spaces were chimerical, elusive,

and untrustworthy.

Perhaps Carné and Prévert had touched the aching, hidden pain of the

city too deeply. The film was skewered by critics and the public: it was too

expensive, it took too much electricity, it was too long in the making, too

pessimistic and psychophilosophical. Georges Altman, reviewer for the com-

munist L’Écran français, described “these nouveaux mystères de Paris [italics

mine] as a new and violent vision of a Paris mired in privation, rotten with

its black market, withered in its unfriendliness.”

44

Despite the caustic dis-

paragement, the defenders of the film argued that its vision of Paris and its

somber, forgotten places rang true. Carné, according to even negative reviews,

had recreated Paris with “rigorous exactitude.” The combination of studio

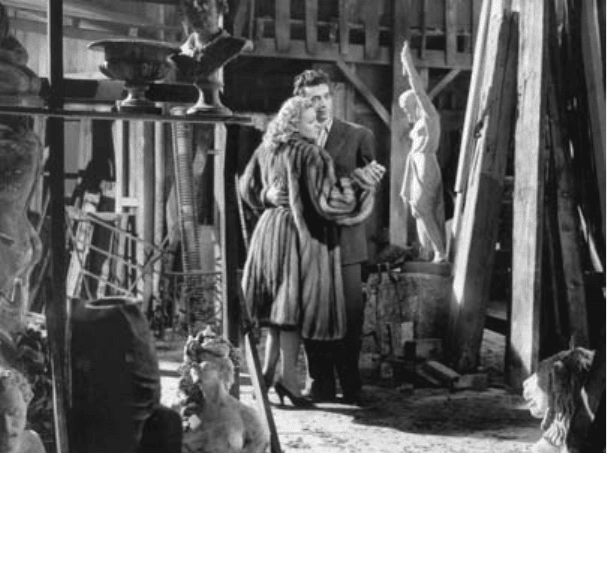

figure 25. Nathalie Nattier and Yves Montand in Marcel Carné’s Les Portes de la nuit, 1946.

© rue des archives/collection csff.

paris as cinematic space | 231

and location shots had created “a mythic city, a poetic portrait of a city that

is closer to reality than a documentary.” Prévert, Trauner, and Carné had

recreated their eternal Paris:

The boulevard Barbès of “Les Portes de la nuit” is the boulevard du

Crime of “Enfants du paradis.” The throngs descending the stairs into the

Métro is the same as that crowding the entry of the Funambules Theater.

Stairs and gates, alleyways and streetlamps, railroad tracks, luminous

canals in the night, once again we soak in the atmosphere of Paris. Once

again, the setting, the mood fills us with wonder and seduces us.

45

It would be difficult to argue that the film portrayed “life as it is led” in any

naturalistic way. Ginette Vincendeau argues that the achievement of poetic

realist films such as Les Portes de la nuit was to create authentic characters

connected to their environment who, despite the artificiality of the sets,

possessed the capacity to stand for reality.

46

This was due in part to the ac-

cumulated visual recollection of Paris, which began most importantly with

Zola, and in part to the evocative sets and lighting or atmosphere that per-

meated the screen. But the film also depicted the tensions between accepted

perceptions of Paris as the capital of modern splendor and the disregarded

spaces that pierced a far more decentered geography. The depiction of this

dark and dreary postwar reality captured the moral unease, the anxiety over

ruin and loss, that permeated a troubled city.

Both Carné and Prévert continued to create a Paris imbued with the

dramatic and aesthetic vision of poetic realism, although by the end of the

1950s they had fallen out of favor with a public that was turning its atten-

tion to the more complicated imagery of the nouvelle vague. Carné’s L’Air de

Paris (1954),

47

starring Jean Gabin as the “papa” for the young men at his

gym and Arletty as his tough wife, was an ardent portrait of working-class

life and ambitions. Following the hopes of the young boxer André (Roland

Lesaffre), Carné takes us on a tour of Paris: the boulevard de Grenelle, the

Île de la Cité, the Île Saint-Louis, Baltard’s sheds at Les Halles, a wretched

hotel populated by North African immigrants where the hotel manager prof-

its by jamming his “dirty clients” together “five people to a bed.” Guided by

the songs of Francis Lemarque and Yves Montand, the city is a theater of

life for young André. But his flirtation with the wealthy bourgeois world of

his girlfriend ends in heartbreak. The social differences are too difficult to

232 | chapter five

surmount. He is rescued from despair by Gabin and brought back into the

warm fold of his working-class roots.

Prévert followed Les Portes de la nuit with a series of Paris films that reit-

erated his populist imaginary: La Seine a rencontré Paris (1957), Paris mange

son pain (1958), Les Primitifs du XIII (1958), and the incomparably nostalgic

Paris la belle (1958). Although stylistically striking, both Carné’s and Prévert’s

film projects late in the decade lost much of their defiant, rebellious quality

and instead projected a simpler, sentimentalized portrait of a Paris that ex-

isted only in wistful memory. Prévert’s deliberately black-and-white world,

where “the bad are on one side, the good on the other,” where “the rich are

almost always malicious, the poor almost always generous of heart,” had less

relevance as the war and reconstruction years faded into the past.

48

His de-

tractors increasingly took him to task, while admirers spent more and more

time defending his vision as an authentic, populist poet. Carné’s vision was

criticized as passé, one reviewer comparing his portraits of Paris to the ubiqui-

tous images on postcards. The scenes of working-class life were too beautiful,

too sensuous and luminous: “It’s terrific. But it is not enough to make a film,”

and not enough to take seriously even when you add the boxing gym.

49

The darker reality of Paris was also taken up in a variety of 1950s policier

films and gloomier noir portraits of the city’s life. Filmmakers were preoc-

cupied with the decayed and ruined urban landscape, and their visual nar-

ratives entered the public debate about the city’s spaces and its future. The

films discussed here chart the ways in which the screen probed urban blight

and the layers of detritus that dominated much of the capital’s landscape.

René Clair’s Porte des Lilas (1957) is a poignant portrait of poverty and exile

in the northeast working-class districts of the city.

50

In the ironic détourne-

ment of street naming, the porte des Lilas brought to mind springtime and

the guinguettes on the city’s outskirts. But for all the nostalgia about the sur-

rounding environs and their enchantment, the edges of Paris also formed

a ferocious zone of social injustice and conflict. There was long-standing

anxiety about the mysterious badlands, the terrain vague, that enveloped the

city. The decentered urban landscape seemed to shatter along its margins

into areas of exile and oblivion. Film brought to the surface the spatial an-

tipode or inverse of the centralizing spaces of the monumental capital. The

porte des Lilas created by the film’s set designer, Léon Barsacq, constructed

partially in the studio and enhanced by lighting, was a derelict landscape of

urban misery shrouded in rain and snow. Dilapidated housing, dreary mud

paris as cinematic space | 233

streets, railroad yards and smokestacks, rubble, and the notorious zone com-

pose the bleak cinematic landscape. The film mirrored the wretchedness of

the neighborhood’s reality. Contemporary reports described the porte des

Lilas as a maze of shacks, garages, and tool sheds, ill-kept gardens with their

rabbit and chicken cages, gypsy wagons, and broken-down trucks. Here

lived an erstwhile community of ragpickers, scrap merchants, chair caners,

beggars, panhandlers, and all those who make their living in the classic in-

formal economy of the indigent. To alleviate what was designated as slum

conditions, the city of Paris had already begun constructing 336 emergency

housing units for the poor at the porte des Lilas. By the mid-1950s Robert

Auzelle was carrying out his site studies of the zone between the porte de

Pantin and the porte des Lilas in preparation for redevelopment.

But rather than reiterating the grotesque underworld that dominated

the public’s imagination about slums, the film crafts a very human visual

rendering. The neighborhood vagabond Juju is played by the actor Pierre

Brasseur, who also starred as Frédérick Lemaître in Les Enfants du paradis.

Juju shares a dingy apartment with his mother and sister, who pick rags and

sell them at the local flea market. In his only film role, the folk singer Georges

Brassens plays a destitute musician who croons his mournful songs at the

local bistro where customers chase away the monotony of life. Young boys

on the edge of delinquency harass the neighbors and carouse in the street.

The only outsiders who dare enter this miserable domain are a dangerous

criminal and the police chasing him. Yet despite the misery and meanness

of life, Clair presents the neighborhood as a noble community with its own

practices and tactics for survival. They make do with the simple pleasures

of song and camaraderie. Their solidarity diminishes the misery, and they

organize to defend themselves against the criminal in their midst. The film

offers a cinematic glimpse into an unknown world of destitution outside

the bounds of affluence and urban sophistication. Juju provides the film’s

psychological portrait. He is unsightly and unkempt, yet despite his pitiable

condition as neighborhood vagrant, moocher, and butt of local jokes, Juju is

not what he seems. He is a man of gentle character and noble heart, a version

of the all-knowing, all-seeing vagabond, a mythical presence on the streets of

Paris. Juju befriends all those around him, including his beloved Maria (the

starlet Dany Carrel), the café-owner’s daughter, whom he whirls around the

dance floor at the July 14 musette. It is the only relief from the grueling dull-

ness of their lives. The film is drenched in loneliness. In Clair’s soft, drifting

234 | chapter five

melancholy, the two friends, trapped in hardship and isolation, make plans

to flee the ravages of a disenchanted urban world: “When you are rich, Juju,”

asks Maria, “will you take me to the Midi?” For both of them, the polished,

egotistical killer who has hidden out in this forgotten neighborhood offers

the only excitement. He is the epitome of the arrogant bourgeois martinet.

His haughty remark that “money is always easy to find” is aimed at Juju and

hits him like a bullet to the heart. Despite Juju’s altruism and his compas-

sion for those around him, he ends by destroying Maria’s happiness, illusory

as it may be, and murdering the criminal to defend her. He is an aesthetic

reflection of the social outcast suddenly captured by the camera and made

visible on the surface of the city.

In Les Lettres françaises, the critic Georges Sadoul pointed to the film’s

underlying humanity, “the confidence in men, even the most fallen. Tender-

ness and emotion fill the air of this porte des Lilas.”

51

Clair’s objective was to

reveal a hidden world and create a cinematic realism that was “more striking

than reality itself”—hence the studio version of the seedy neighborhood, the

heavy use of slang, and the visual spectacle of poverty. Clair argued that the

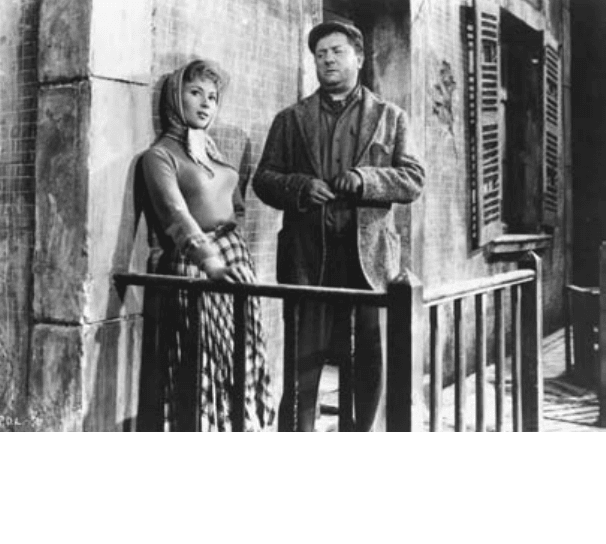

figure 26. Pierre Brasseur and Dany Carrel in René Clair’s Porte des Lilas, 1957. © rue des

archives / the granger collection, new york.

paris as cinematic space | 235

slang and mannerisms of this unknown place were one of the film’s principal

characters.

52

He adopts the role of an ethnologist embarking on a voyage of

discovery to a strange land. Working-class behavior, gestures, language, and

dialogue became the material of visual investigation. The written language

of Léo Malet and Henri Calet are brought to life. The film was nominated

for an Academy Award and won the Danish Bodil Award for Best European

Film. Nevertheless, L’Humanité accused Clair of being a petit-bourgeois

anarchist with a romanticized view of the twentieth century—tender and

sentimental. L’Esprit took him to task for too much “emotional populism”

and sentimental flânerie. No doubt there is an exoticism, a purely cinematic

pantomime of the forgotten world of poverty that Clair imagined.

53

Yet the

extreme stylization infused Paris with poetic melancholy and gave this disre-

garded urban landscape a powerful sense of nobility and classic tragedy—or,

perhaps even more to the genre’s point, a sense of fatalism. The characters

are mythic archetypes, the scenarios literary, almost ethereal in quality.

The expressive visual presentation and implied social criticism in Clair’s

Porte des Lilas was close to that in the renowned documentary on the terrain

vague just to the north, Jacques Prévert and the photographer Eli Lotar’s

documentary Aubervilliers (1945).

54

Combining both surrealist and realist

sensibilities, Lotar had already produced powerful photographs of the abat-

toirs at La Villette and an evocative series entitled “Somewhere in Paris” as

early as 1929.

55

The uneasy images in both series evoke the harsh environ-

ment along the margins of the city that fascinated the avant-garde. By the

1930s Lotar had turned to documentary film. Twenty minutes in length,

Aubervilliers is a jarring exposé that reiterated this same vision of the city’s

edge. Passing through the porte d’Aubervilliers in 1952 and in part react-

ing to the film, the urban commentator Jean-Paul Clébert remarked that

the “poetry and horror of the zone had a great many times been decried,

inspected, photographed, filmed, reconstituted in studio, exported for for-

eign countries as national heritage (French culture and taste), utilized for

literary, artistic, moralistic, political ends and forced under the nose of the

indifferent by all of the describers of the social fantastic.”

56

As a marginal

space, Aubervilliers offered a spectacle of dissolution and entropy. It was

an alien life that contradicted the splendor of central Paris. Prévert spoke

the poetic commentary for the film. The music, performed by Germaine

Montero and Fabien Loris, was by Joseph Kosma, whose forlorn “Gentils

enfants d’Aubervilliers” was especially poignant: