Wakeman Rosemary. The Heroic City: Paris, 1945-1958

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

66 | chapter two

Those who sought the simple magic of the city in the late 1940s and

early 1950s dug deep into an historic treasure trove of characters haunting

the streets. This vision of Paris was produced from a long heritage beginning

with Sébastien Mércer and in which the naturalism of Zola held particularly

strong sway. The novelist Armand Lanoux (later a winner of the Prix Gon-

court) explored the city’s revered social landscape on a variety of sentimental

journeys. In “Physiologie de grands boulevards” (1954), Lanoux introduces

the reader to old Alphonse, a junk dealer at the Saint-Ouen flea market,

and Louise, a ragpicker who sings comic opera at the top of her lungs on

the rue de Maubeuge. They exude the innocence of la France profonde, and

indeed Lanoux’s writings were by and large suffused with folkoric images

d’Épinal. It is through these two characters “out of Dickens” that Lanoux

chooses to introduce the local zinc (bar) from where the street scene along

the boulevards is inspected.

5

In Physiologie de Paris, also published in 1954,

Lanoux explains that in Belleville (that native soil of Paris) certain “urban

races” survive: “They are archetypes only thought to exist in literature. The

Saturday-night drunk, the hard-slapping shrew, the street urchin puffing on

his smoke on the way home from school, the virtuous sister who raises the

brood are preserved here in a living serial drama.” At night the only people

on the street are classic characters: bike cops and beat cops, sharks and pro-

vocateurs.

6

It was above all these working-class districts in the east to which

this poetic sense of distinct place and culture was ascribed. The historian Jean

El Gammal remarks that they were infused with an atmosphere of nostalgia

and sentimentality in the late 1940s and 1950s.

7

In Jules Romain’s Portrait de

Paris, published for the city’s two thousandth anniversary in 1951, Catholic

social reformer Robert Garric wandered the city to summon up the mythic

world of the “people of Paris.” Their neighborhoods had

charming names: Ménilmontant and Charonne, Bercy and Montrouge,

les Gobelins, La Villette and Grenelle, Montmartre, Belleville. What cit-

ies within the city! What closed little worlds, so distinct, their streets and

neighborhoods with such intense personalities. Some are animated and

noisy, with an eccentric cheeriness; the cries of the street peddlers, the

songs of the shopkeepers can still be heard. And others seem shadowed by

sadness. . . . To live in one of these neighborhoods is to penetrate little by

little into the unique sensibility of those who live there, to understand their

habits, their memories, the pride of their traditions and their past.

8

the landscape of populism | 67

Guided by social Catholicism, Garric had created the Équipes sociales

movement in 1920 to educate the working classes. He began the first study

circle at Belleville. In his “friendly flânerie in the streets, remembering, listen-

ing, trying to hear the voice of the people,” Garric evoked Belleville and

its great, endless street, so varied and lively, its church, the memories

of the Commune, its cinemas and theaters, its blazing cafes, and this

ardent, mixed up sense of a crowd that is just as ready for merrymaking

as for a meeting. It is on these streets, on the high terrace of the Buttes

Chaumont, one of the most beautiful sites in Paris, in these dwellings,

where if we listen, without speaking, if we remain silent, we can hear the

voice and catch the heart of the people.

9

In this populist ode Garric portrayed a concrete, tangible image of Pari-

sians living in their own milieu. Although bathed in naturalism, this imag-

ery clearly imparted the edifying moral that the quotidian, workaday world

was a valiant one. This passion for discovering the quintessential qualities

of ordinary neighborhood life was a voyage in search of the truth. It was an

invented ethnographic exploration, an unearthing that would affirm the true

qualities of Frenchness.

The pictures invented by urban observers like Lanoux and Garric bor-

der on the anachronistic and almost repeat the stereotypes of Eugène Sue

in Les Mystères de Paris, published in 1841. Here was a taste of the piquant,

the exotic, that made venturing into these districts tantamount to a voyage

into the interior of an alien land. It was an exploitation of the mysterious and

labyrinthine picturesque. These writers constructed, in the words of André

Wurmser, who reviewed three of the publications on Paris in Les Lettres fran-

çaises in 1952, “a halo of false charm” and “magical evocations of the scenery

of our childhood like one of those insipid historical novels.” Wurmser was

incredulous about “the beauty and charm of Paris” that could be found in

the city’s ancient neighborhoods: “These heartrending, charming houses of

tuberculosis,” he snidely remarked, “are admired today by amateurs . . . who

stroll by them, but don’t have to live inside.”

10

Yet this mixture of fiction and

reality transposed the moral dilemmas of the times onto the city’s landscape.

They reflected the uncertainties of the present and the fears of loss. The scenes

invented by urban observers of conviviality and neighborhood fidelity and

the salt-of-the-earth qualities of the working people were the converse of the

68 | chapter two

actual civil strife that had fractured the public domain in the 1930s and 1940s.

The purges that marked the early postwar years threatened to destroy the

familiarity and trust normally associated with quotidian existence. The time-

lessness and humanity evoked in the city’s neighborhood landscape pacified

the isolation, mistrust, suspicions, and fear that had dominated the spaces of

the city. These were depictions of the majority of everyday people as les bons

Français. Genuinely patriotic, they had remained steadfast through the dark

years and shared in the community of suffering and resistance. The world of

quotidian existence is made harmonious, eternal. Parisians had reconquered

the spaces of their public lives. Their physical presence in the streets, their

resurgence as an enduring icon reactivated an intimately familiar memory

of the city as home. Robert Garric described the “people of Paris,” recruited

from every corner of the country: “They have their gatherings, their holidays

. . . their music, their songs, their newspapers. And Paris is the melting pot,

it absorbs them all.”

11

Hence this outpouring of urban writing and imagery was more than just

musings about a bucolic past. As an invented discourse it functioned entirely

within the present as a cognitive urban mapping. The way to discover this

eternal humanistic world was by walking through it. “There are hundreds

of kilometers to explore,” Jean-Paul Clébert declared eagerly as he set out

on his itinerary to discover the unknown Paris insolite: “each street, alley,

impasse, cul-de-sac has its personality, its own life, each is an îlot of houses,

hovels, sheds, and chicken coops, its closed universe, its bistros, storeown-

ers, its prostitutes, its inhabitants, habits and customs, that have nothing to

do with their neighbors, and its architecture, its own spirit, its opinions, its

work.”

12

Space is transparent and legible from within. Clébert’s intent was

to traverse and illuminate this fragmented landscape of distinctiveness. The

urban biographer Henri Calet also journeyed into the interior of eastern Paris,

where he had spent a part of his youth. In Le Tout sur le tout, Calet described

an “immense village of streets . . . descending, snaking, with country names

. . . rue des Pavillons, rue du Soleil, rue de l’Ermitage, rue du Guignier, rue

des Soupirs, rue des Rigoles, rue de la Mare, rue des Cascades. . . .”

13

This

naming of streets, which pervaded virtually this entire genre, functioned to

restore memory and place, to shift the public gaze from the grand boulevards

down into the neighborhood districts and to equilibrate the city’s geography

around a far more decentered axis. In The Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin

noted this strange power of names, spaces, and allegorical signification. There

the landscape of populism | 69

is a peculiar voluptuousness, a sensuality in the naming of streets.

14

They

revealed the neighborhood’s secrets. Spatial sites and their symbolic objects

juxtaposed and provided continuity between the past, present, and the future.

They illuminated the teeming activity, the cacophony of places and spaces, the

“what took place here” at the heart of Paris’s vast collectivity and rendered

perception richer.

Inventing the Populist Landscape

Although riddled with political tensions, this mythic landscape of a self-

actualizing Rousseauian people persisted from the late 1940s through the

mid-1950s to provide the moral landscape upon which national unity could

be imagined. In this invented topographical discourse, the public spaces of

the city—that is, the streets and alleyways, the bistros and markets, the lo-

cal festivals and street dances—were the places associated with their world.

The interior of the workplace or home is rarely invoked. Instead, the street

becomes a type of collective domestic interior. We catch a glimpse of les Pa-

risiens in movement, strolling after dinner or dancing in the neighborhood

square, on their way to work, crossing Sébasto to Les Halles, and traversing

the boulevards and river quays. The street space claims existence when it is

filled with human life. The interactions between human beings and between

social groups were conceived as space filling. On summer evenings, families

claimed a space on the sidewalk for a candlelight dinner and the chance to

chat with neighbors. Saturday night meant the accordéon musette at the local

café or dance hall. On Sunday afternoons families and couples promenaded

along the boulevard or in the nearby park. Among the most well-known evi-

dence for this poetic spatiality was that produced by the photographer Robert

Doisneau. Even a superficial reading of his Parisian portraits evidences the

absorption with the commonplace, with neighborhood life, and also with the

apprehension that this authentic Paris would vanish. For Doisneau, Paris

was moving because it was threatened, provisional, ephemeral. His intimate

black-and-white photographs captured daily life in the everyday spaces of the

city: men play pétanque in the park, old men gather around a table on the

sidewalk for cards, children stage a roller-skating race, and religious proces-

sions parade through the quartier on feast days and to celebrate marriages

and first communions. Street vendors provide a continuous carnival atmo-

sphere in Doisneau’s vision, selling everything from hot chestnuts, french fries,

70 | chapter two

and sandwiches to cigarette lighters and flowers. Delivery carts and wagons

disgorge their contents onto the sidewalks in an animated streetscape that

shifts with the daily and weekly rhythms of exchange.

15

The local church or

charity bazaars known as kermesses, the fêtes foraines and open-air dances that

celebrated local holidays and the quatorze juillet were legendary and awaited

with immense anticipation. These neighborhood scenes were powerful and

unique. As part of the machinery of working-class cultural production, they

obscured France’s social and ideological struggles and diverted attention away

from the shame of occupation. The city’s citizens were unified, reassured of

their human bonds. The sense of social connection implicit in these renderings

was remarkable. The images became fixed metaphors for the noble quality of

the small-scale environments that made up Paris. Firmly embedded in the

political and social vision of the early postwar years, they immortalized the

idea of neighborhood public life and attempted to naturalize the popolo as

part of the vernacular landscape. Endlessly objectified and moralized, these

images of the people were rooted in the pays of Paris as a textual allegory for

the resurgence of an eternal city.

Two influential urban explorers were perhaps most responsible for invent-

ing this populist spatial dynamic and the entire working-class topos: Jacques

Prévert and Willy Ronis. Their portraits in poetry, song, and photography

bathed the working-class districts of Paris in the glow of poetic humanism.

Of the two, the poet, playwright, composer, and screenwriter Jacques Prévert

was perhaps more identified with the Paris of the late 1940s and 1950s than

any other individual.

16

His life and work were in essence Parisian. Prévert

was born into a straitlaced bourgeois family and raised on the rue du Vieux-

Colombier in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. His austere grandfather Auguste

Prévert was director of the city’s main charity office on the rue Monge.

Over the course of his childhood, Jacques accompanied both his father and

grandfather into the city’s northern districts to visit the misery and poverty

of the capital. From La Chapelle to La Villette, from the canal de l’Ourcq

to the canal Saint-Martin, from Ménilmontant to the Buttes-Chaumont,

he observed firsthand the traditional street scenes of working-class Paris in

the first half of the twentieth century in all their richness, complexity, and

misery. Revealing the mysteries of these unknown places and artistically

rendering the spectacle of the street in the city’s poorest neighborhoods

became his passion. And in the parlance of the day, even the city’s poorest

slums were identified as “working class.” Prévert shared this humanist point

the landscape of populism | 71

of view with sociologists studying the common people, who will be treated

in a later chapter. The purpose of both was to give voice to the voiceless and

expose the conditions in the city’s marginal places. The familiar images of

burly workers and artisans, the rowdy street kids, the elegant Japanese foot-

bridges and barges of the canal Saint-Martin, the old haunts of the “children

of paradise” along the rue du Faubourg du Temple all became part of the

drama and melancholy of Prévert’s poetic landscape. As a flâneur, he fed on

sensory data. Assessing Prévert’s extraordinary popularity during the 1940s

and 1950s in Les Lettres françaises in 1956, when Prévert was rising to the level

of “national poet,” the journalist René Lacôte argued that he was a rare case

“of poetic genius defined by the marvelous connection between the poet’s

sensitivity and popular sensitivity.”

17

The experience of Prévert’s youth also provoked a political reaction to the

searing social injustices all too evident in the city’s landscape. He attacked

the deliberate ignorance of conditions for the working classes laboring in the

capital’s industries. He decried the absence of “the people” from the city’s

artistic whirl, whether theater, film, or literature. Prévert’s writing was anti-

establishment and consciously scandalous, bent on creating a new universe

that defied official versions of the truth. He was a familiar figure among the

avant-garde gathered at the bistros of Montparnasse in the 1920s and the

golden triangle of cafés on the place Saint-Germain-des-Prés in the 1930s.

Although never an official member of the Communist Party, Prévert was im-

mersed in the prewar blend of surrealism and anarchism. His Groupe Octobre

(1932–36) was a theatrical agitprop troop that staged caustic buffoonery and

social satire and was often called upon for performances at Communist Party

political rallies in Paris. His writing was insolent and unruly, eternally rebel-

lious, with a candor and simplicity that belied its underlying power. And for

those reasons, Prévert left Paris in June 1940 with thousands upon thousands

of others, by Métro, on foot, by truck, bus, and even riding on the back of

a cannon, along with his longtime allies Joseph Kosma and Brassaï. They

were followed into exile in the south of France by Marcel Carné, Alexandre

Trauner, and a coterie of shaken artists.

Two factors were critical to Prévert’s influence and popularity in the 1940s

and 1950s. First was his relationship with the film director Marcel Carné and

the screen actor Jean Gabin, as well as the series of tour-de-force films that

resulted from their artistic alliance. This troika had already worked together

on two important prewar films, Le Quai des brumes and Le Jour se lève. Prévert

72 | chapter two

provided the surrealist avant-garde style, Carné the gritty realism of the

streets, and Gabin the portrayal of the archetypal working-class Parisian in

a series of films that were among the most popular of the 1950s. The second

was the publication in May 1946 of his first anthology of poems, Paroles, with

a cover photograph of wall graffiti by Georges Brassaï. Patched together by

René Bertelé from Prévert’s newspaper articles and reviews, cabaret songs,

and scribblings on the backs of envelopes and bistro tablecloths, it was an

overnight sensation and catapulted Prévert from the literary margins to make

him the idol of a new generation. As in many of his poems, Prévert creates

an aesthetics of emotion in “La Rue de Buci maintenant” that captures the

somber occupation mood in the normally vibrant market street of Saint-

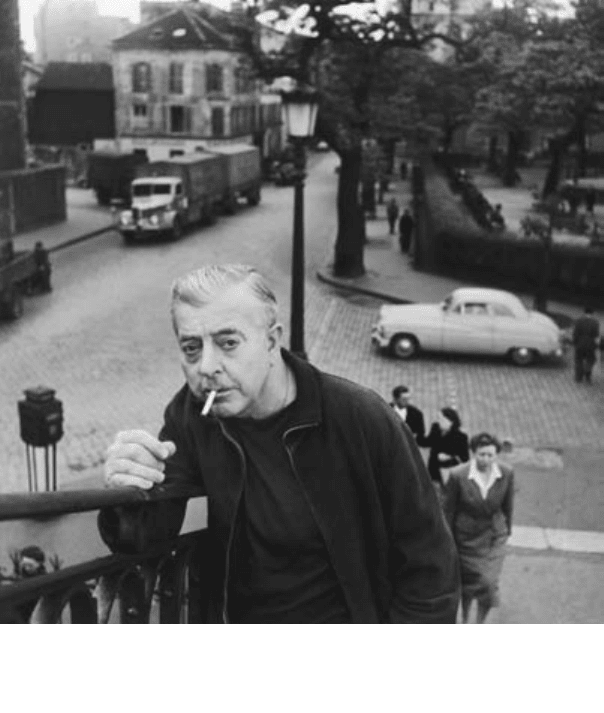

figure 5. Jacques Prévert, 1955. © robert doisneau/rapho.

the landscape of populism | 73

Germain-des-Prés. The city’s upset and grief are not repressed. Emotion

and compassion reign in Prévert’s vision of the world:

Where has it gone

The crazy little world on Sunday morning

Who has lowered this awful dusty veil

And the irons on this street

This street once so happy and proud of being a street

like a happy girl and proud of being naked

Poor street

Now abandoned in the neighborhood

Itself abandoned in an empty city

Poor street

Gloomy corridor leading from one dead spot to another dead spot

Your lonely, skinny dogs and your gross war wounded

who are so skinny themselves. . . ..

18

Even before its publication, copies of Paroles were passed hand-to-hand

through the underground as a form of resistance to the occupation. The week

of its official appearance in Paris, 5,000 copies were immediately snatched up,

and over the next few years over 100,000 copies were sold. It was followed in

1951 by the publication of Spectacle. Prévert’s parole—as poetry, oral literature,

song lyrics, and film dialogue—authenticated the informal language of the

everyday and provided a sense of linguistic consciousness. It was the spoken

idiom of the people of Paris, found in the spaces of their city. In the poem

“Et la fête continue,” from Paroles (put to music by Joseph Kosma and Yves

Montand), he evokes the atmosphere of a local zinc:

Standing by the bar

At the stroke of ten

A tall plumber

Dressed for Sunday on Monday

Sings for himself alone

Sings that it’s Thursday

That there’s no school today

That the war is over

74 | chapter two

And work too

That life is so beautiful

And the girls so pretty

And staggering by the bar

But guided by his plumb line

He stops dead before the proprietor

Three peasants will pay and pay you

Then disappears in the sun

Without settling for the drinks

Disappears in the sun all the while singing his song.

19

The language of the people was conventionally marginalized as puerile and

uneducated. Their everyday lives were deemed repetitive and meaningless,

outside formal history. With Prévert, this universe became heroic. The petit

peuple are brought on to the stage of public life along with their grammar and

speech, their aesthetic. A deep humanity returns to the surface of the city.

Just as Prévert gave voice to the people of Paris, Willy Ronis pictured

them. Ronis, along with Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Doisneau, was

one of the most well-known photographers of Paris in the 1950s. The work

of all three men became famous during the heyday of photojournalism im-

mediately after the war, before television became widespread. Millions of

people still learned what was happening in the world through the images

in illustrated periodicals such as Paris Match, France-soir, and Point de vue.

Ronis’s photographs of Paris in the 1950s are not as renowned as those of

Doisneau. However, his work followed an independent, idiosyncratic course

and perhaps reveals a more intense visual inquiry of the city’s ordinary life

and its public spaces. Born at the foot of Montmartre in 1910, Ronis learned

photography in his family’s modest portrait studio on the boulevard Voltaire.

His work was heavily influenced by the new ways of looking at and using the

photograph pioneered by avant-garde artists such as László Moholy-Nagy

and the Surrealists. He eventually spent a long career out on the streets pur-

suing an independent creative course and spearheading the genre of photo

reportage.

20

As the child of Jewish immigrants, Ronis had an acute awareness of

marginality and the dispossessed and was an unswerving champion of the

city’s working class. His objective was to visually portray the more fraternal

society found in the social life of the quartiers populaires. His photographs of

the landscape of populism | 75

the city’s strikes, social movements, and street life were quickly bought up

by magazines such as the communist weekly Regards. With the fall of France,

Ronis found Paris a dangerous place for a Jew. In a hazardous crossing into

unoccupied territory in southern France, he met up with Jacques Prévert

and his troupe of exiles in Nice and eventually joined Alexandre Trauner at

Tourette-sur-Loup during preparations for Les Enfants du paradis. After the

war Ronis returned to Paris, and like many left-wing artists and intellectuals

of his generation, became a fellow-traveler in the Communist Party, of which

he remained a member until 1965. He joined the Groupe des XV, an associa-

tion dedicated to promoting French photographic style, and along with Do-

isneau and Georges Brassaï signed on with the Rapho agency (whose name,

incidentally, was coined by Henri Calet). Ronis became one of its premier

photojournalists, winning the Kodak Prize in 1947 and the Gold Medal at

the 1957 Venice Biennale, among a cavalcade of other honors that spanned

the decade.

21

Ronis created a visual chronicle, almost a memory board, of Paris profond.

He focused his lens on anonymous people recognizable in ordinary space:

strollers along the quai Malaquais, shoppers at the marché d’Aligre, le titi

parisien (street urchins) playing on the buttes of Belleville, lovers kissing on

the passage Julien-Lacroix, Christmas shoppers on the rue de Mogador.

For Ronis, the city only existed in its human, livable dimension. His public

spaces are articulated through human presence and social exchange rather

than through physical artifice. This aesthetic makes Ronis’s photographs

among the principal archives of the city’s life from the 1930s through the

1950s. The photographer becomes a self-actuated passionate flâneur sharing

the same spaces and gaze as his subjects. It is there, looking at his images,

that we chance upon the fragments of lived experience, the daily routines of

work, café life, shopping, promenades, street dances, and fêtes foraines that

defined this particularistic urbanity. It is an expressive ethnophotography,

a voyeuristic peek into an intimate, forgotten world. Ronis’s compositions

bathe the instantaneous moments of the everyday in a sheer unpretentious

honesty. His dictum was to honor his subjects, to reclaim the integrity of

the working-class world of the quartiers. The ordinary is made touching, ex-

traordinary.

22

These were not impromptu shots. The seemingly random social

and spatial formations were purposeful compositions. Ronis constructed a

mise en scène or staging of the action in which everyday urban life becomes

performance. Ordinary people leading ordinary lives become unsuspect-