Wakeman Rosemary. The Heroic City: Paris, 1945-1958

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

86 | chapter two

Boule Rouge, the Barreaux Verts, the Bal des Familles, the Musette, and the

Petit Balcon on weekends to enjoy traditional dances such as the valse and the

java. The proletarian guinguettes (local taverns with dance floors and musi-

cal entertainment) and bals musettes around the edge of Paris in places such

as Montmartre, La Villette, and Belleville, and along the Marne River, were

also renowned entertainment spots. The novelist and poet Blaise Cendrars

captured the atmosphere in the eastern suburbs in 1949: “a tavern, jazz, a

dance, a crowd all night, with little bridges, little lakes, arbors decorated with

Venetian lanterns, stone paths as in Buttes-Chaumont.”

43

The popularity of

both the bals musettes and the guinguettes were enormous during the Libera-

tion years and the early 1950s.

The Parisian Colette Bouisson remembered that “after four years of im-

mobility an explosion of dance shook the city. There had never been so many

evenings of dance, places to dance, clubs, studios, get-togethers, parties . . .

here the waltz, there the tango or even the charleston, while from neighbor-

hood to neighborhood there were outbursts of bebop.”

44

Neighborhood as-

sociations organized open-air dances. In order to attract clients, local cafés

organized bals that usually included amateur singing contests. Accompanied

by a singer and accordionist, people spontaneously broke into dancing in

the streets and around Métro stations. The cellar clubs and streets of Saint-

Germain-des-Prés vibrated with swing and bebop. All functioned as spaces

of transparency and impulsiveness, made even more potent by the politi-

cal meanings of Liberation and the triumph of the classes populaires. Public

dancing, especially bebop and the jitterbug, was the ultimate expression of a

freeing, a liberating of the civic body. Like fêtes foraines, dance halls and bals

publics were places of inversion and experimentation, of misbehavior and act-

ing up, of breaking from the routines of weekday work—places where people

of all backgrounds and every shade of reputation bumped elbows and more

on the dance floor. Even in the late 1950s, the bals continued to be one of

the main institutions of sociability and youthful play. In Michel Déon’s 1958

novel Les Gens de la nuit, young friends find a bal musette called Chez Au-

guste near the place de la République, where they dance to accordion music

played by a blind albino. Although the atmosphere of some thirty couples

crammed together on the dance floor is stifling, filled with smoke and the

smell of alcohol, they can distinguish “the petits employés who, in the evening,

dress in sweaters and loud shirts with unbuttoned collars in an attempt to

look classy in front of their girls.”

45

In her book Les Gens du passage (1959),

the landscape of populism | 87

Clarisse Francillon recounts daily life along the passage Prévost in the 13th

arrondissement. The shy heroine, Denise, is pushed into attending the Bal

Wagram by a girlfriend, where Denise meets a pharmacist who will become

her boyfriend. They watch as the crowd elects the “prettiest legs in Paris.”

The Salle Wagram is packed with young people; “a cloud of dust envelops

the crowd, paper streamers hang in their hair.”

46

The bals populaires and general celebration associated with three events—

the anniversary of the February 6, 1934, political clashes, the May 1 Labor

Day, and the July 14 fête nationale—were perhaps the most anticipated and,

for our purposes, the most politically charged within the context of the war

and reconstruction years. They were fundamental to urban political revelry.

The shared memory of reconciliation associated with them was crucial to the

formation of national community around a united citizenry. The ritual com-

memoration of the defeat of “the attempted fascist coup d’état” in February

1934 and the traditional May Day festivities sanctified the memory and myth

of revolutionary Paris and assured, as Jean-Pierre Bernard has put it, that “the

future would be a mirror of the past.”

47

This invented memory harked back

to a golden age, to the historic moments of working-class solidarity against

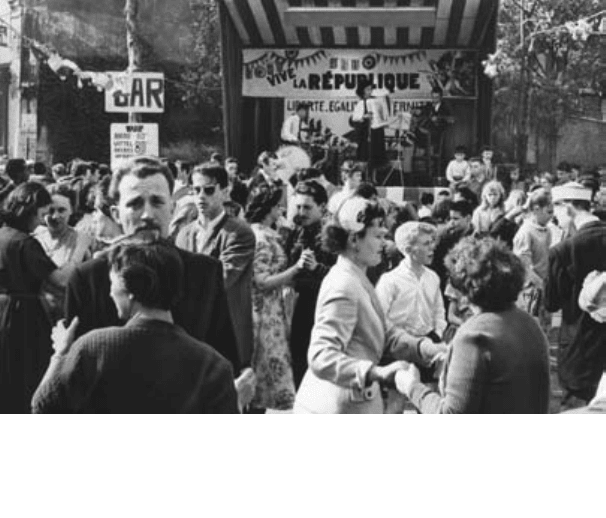

figure 8. Traditional neighborhood bal populaire at the place des Abbesses, 1950.

© l’humanit/keystone-france.

88 | chapter two

the evils of fascism. Each July 14 celebration after the war was an occasion

to relive the Liberation and celebrate the people and their deliverance. It was

saluted with massive street parades and dances, complete with orchestras,

choral performances, and street theater. The celebrations were represented as

a reemergence of the traditional open-air festivities and political spectacle as-

sociated with Parisian revolutionary culture. For the 1948 fête nationale, some

five thousand Parisians gathered at a glimmering place de la Concorde for a

performance by the city’s beloved music-hall and radio stars, foremost among

them Yves Montand and Georges Guétary; the “French can-can”; and a giant

bal populaire that made the square, according to the Christian Democratic

newspaper L’Aube, “truly into a scene of harmony and popular rejoicing.”

48

Newspapers were among the most important promoters and chroniclers of

these electrifying events. They created the public narrative, embellished the

celebrations, and gave them shared meaning. Radio and newsreel coverage

molded them into media spectacles. The Union Nationale du Spectacle and

the communist newspaper L’Humanité organized open-air extravaganzas at

symbolic hubs of working-class life: the place de la République, the porte

Saint-Martin, and the porte Saint-Denis in the northern districts. Enormous

crowds listened to the People’s Choral Society of Paris and the Choral Society

of Suresnes sing and recite from the historic texts of the French revolutionary

tradition. Dancers from the Opéra Ballet performed “revolutionary dances”

in full costume.

49

Musical performances such as these consecrated the public

realm and acted as theatrical devices for inaugurating patriotic citizenship

and reviving populist collective traditions as well as the myths of fraternity

and solidarity. A veneer of harmony reigned in the quartiers populaires. The

proximity of space and the familiarity of these iconographic moments, the

sense that they occurred amid the plain everyday realities of working-class

life, gave the urban landscape the texture of populist theater.

The largest bals populaires to celebrate the fête nationale were at the Bastille,

the place Voltaire, and the place de la République. Support for these events

came from a variety of sources ranging from city hall to neighborhood fire-

houses and businesses, newspapers, and local school budgets. In this sense

they were deeply embedded not only in social community, but in the political

life of the city. In 1949 for example, the Paris municipal council sponsored

the major bals traditionnels at the place de l’Hôtel de Ville, the place de la

Bastille, the place de la Nation, the place Armand-Carrel, the place Victor-

Basch (at the Alésia-Maine-Châtillon intersection), the place Gambetta, and

the landscape of populism | 89

the place Voltaire. As well as hosting these citywide events, complete with

fireworks, the municipal council’s Commission des Fêtes donated over two

million francs to arrondissements and quartiers in need of public subsidies

to pay for their local revelry,

50

although a small entrance fee usually helped

to offset costs. The neighborhood versions sponsored by the local firehouse

were the occasions for vast street parties that were legendary in their extent

and enthusiasm. Consequently, no one centralized spectacle dominated the

reverie. Instead, the merrymaking was spread out across the spaces of the city

in a multiplicity of decentralized locations. All of them featured live music,

usually a small orchestra installed on a temporary platform in the main square

decorated with traditional Venetian lanterns, with the space around given

over to dancing. Their character was spontaneous, the inversion of everyday

normalities, a “bursting” of the personal into the public domain. Normally

private people grabbed partners and danced into the streets, interrupting

traffic and bringing their neighborhoods to a standstill. Whatever their size,

they were populist festivals, celebrations fraught with political overtones.

Collective action was tempered by this reversion to public rituals that

were deliberately traditional in their structure, décor, and social comport-

ment, and yet reiterated endlessly the moment of carnivalesque rebellion

of the Liberation itself. This juxtaposition of tensions—a ritualized calling

for both social harmony and social revolution, looking back to the past and

ahead toward the future—charged these events with intense meaning. They

were a form of magic theater. Describing the 1945 fête nationale, L’Humanité

affirmed that “we have found once more the paper lanterns, the canopies,

the garlands and flags, the little platforms on the square, the neighborhood

orchestras and accordion players, with couples dancing and drinking in the

street . . . and the floodlights and fireworks after all these years of blackouts!”

But the festivities represented more than just merriment, because “one sensed

in the popular joy of this July 14 a new republican fervor and an affirmation

of the vitality of a people who want with all their hearts and energy to rise

from the ruins and construct a new France, strong and happy.”

51

In 1950

neighborhood businesses and civic organizations inaugurated a week of fête

nationale celebrations in Montparnasse that culminated in the “Nuit du 14

juillet.” From the carrefour de Rennes to the carrefour de l’Observatoire, the

neighborhood was strewn with colored electric lights, Venetian lanterns, and

patriotic decorations. The bistros sponsored live music and dancing, especially

at the carrefour Vavin, where the liveliest action took place.

52

Mobs of people

90 | chapter two

descended on Montparnasse for the festivities. What is significant about this

revelry is its extent. To refer to Bahktin once again, the folk festival of the crowd

must be concrete, sensual, a visible form of their mass and unity. It provides

them with a sense of historic immortality, the uninterrupted continuity of

their becoming and growth. The festivities are the victory of the future over

the past, the victory, Bakhtin argues, “of the people’s material abundance,

freedom, equality, brotherhood.”

53

Bakhtin’s point of view captures exactly

this performance quality and utopian hope for French rebirth as it overflowed

in the public spaces of the city. Neighborhood after neighborhood, suburban

town after suburban town fell under its spell and sponsored celebrations that

were actively reported in the media as a sign of renewed vitality. The mer-

riment was couched in traditional custom, but transmitted in the spirit of

progress and commitment to the future.

Much like the week-long neighborhood bash in Montparnasse, the galas

and celebrations organized by suburban municipalities and by philanthropic

societies raised money for needed projects and were symbols of local boos-

terism. The reports in the newspaper L’Avenir de la banlieue de Paris (which

served the suburban ring south of Paris) for 1954, 1955, and 1956 give a

good indication of the extent of this revelry.

54

The May 1954 Springtime

Festival at Plessis-Robinson featured a cavalcade of song, dance, sporting

events, and open-air theater. Folklore and ballet troupes, judo, gymnastic

and trapeze exhibitions, dancing, and a grand ball attracted such enor-

mous crowds that organizers were forced to turn people away. In June 1954

Choisy-le-Roi organized a Fête des Gondoles that featured a procession

of amateur events, all serenaded by the volunteer Choisy Music Band. At

Cachan the June 1954 Grand Kermesse des Écoles to support the colonies

de vacances (summer camps) demonstrated the local political squabbling

over these events and their money-making importance. The city’s centrist

administration lauded the charity bazaar as the most successful and lucra-

tive ever attempted. Local musicians and comedians entertained the crowds.

An evening concert and community dance was attended by nine hundred

paid entrees. In a settling of scores, the success of the 1954 kermesse was dis-

tinguished sharply from the “dismal failure” of 1947 organized by the com-

munists, although “they ceaselessly use support for public schools to attack

the mayor and for political propaganda.” At Clamart the local Commission

des fêtes and the mayor clashed over support for a springtime festival on the

place de la Mairie. The mayor sided with local businesses sponsoring the

the landscape of populism | 91

reverie as an alternative to the traditional fête foraine. On the other hand, the

commission (packed with traditional fête foraine backers) washed its collec-

tive hands of the whole matter and refused to “take responsibility for any

accidents that might occur.” However, both the commission and the mayor’s

office could agree on the authorization of a fête champêtre, or country fair,

organized by the Association des combattants prisonniers de guerre de la

Seine, that was predicted to draw some thirty thousand to forty thousand

people to a local park site. The justification was the business it would bring

in for local tradesmen.

These few examples among a host of others make it clear that local event

committees and city halls in the suburban townships were responsible for

organizing substantial entertainment to rival that produced by their neigh-

bors. Part city boosterism, part fund-raising for schools, part money makers

for local business, they also represented community spirit and collective play.

They were infused with a sense of civic showmanship from a multitude of

angles—onstage, in various sport, music, and dance competitions, in cos-

tumed parades, and on the dance floor. The organized entertainment was

usually a combination of amateur groups and professionals that showcased

local talent and local public sites, from municipal halls and sports stadiums

to central squares and city halls. These municipal spectacles essentially me-

diatized suburban public space and the collective activities that took place

within it. They are signs of the spatial splintering and the intensely decentral-

ized nature of urban spectacle in the 1950s. And they were not just slipshod

local talent shows. A February 1955 municipal gala organized by Issy-les-

Moulineaux drew not only the local community, but thousands from neigh-

boring communes and “even from Paris” to hear Tino Rossi and a host of

other legendary entertainers in its “acclaimed Salle des fêtes.” In April of the

same year, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre organized an evening dance at the municipal

hall that was featured live on the radio program “Ce soir, on danse . . .” and

included entertainment by the famed accordionist Étienne Lorin. At Antony,

the springtime festivities featured Miss Europe 1955, the award-winning and

immensely popular entertainment group Arc-en-Ciel from the Renault fac-

tories, and a host of local amateur performers. The municipality of Plessis-

Robinson organized the Île-de-France Music Festival in June 1955, which

allied a wide range of official organizations from the Comité officiel des fêtes

de Paris to the Fédération des musiques populaires de Seine et Seine-et-Oise.

Plessis-Robinson’s favorite sons, backed by the Plessis-Robinson amateur

92 | chapter two

choir, publicized the event on the Saturday-night broadcast of the popular

television show Télé-Paris. The festival featured concerts and musical events

at the principal public spaces of the township. An official parade snaked

through the streets from the main place des Martyrs de la Résistance to the

local sports stadium, where an enormous concert ended the afternoon. The

entertainment continued throughout the evening with gala performances by

a host of singers and stars and ended with a massive fireworks display.

As the ultimate in this kind of populist theater, the carnivelesque fêtes

foraines were the object of veritable cult worship. Urban carnivals as civic

celebrations proved much longer-lived than might initially have been ex-

pected. As a modern form of amusement they reached their heyday dur-

ing the reconstruction years immediately following the Second World War.

They were vast parties whose subtext was clearly about control over the

spaces of the city. The Paris historian and observer André Warnod listed

five major fêtes foraines traditionally celebrated in Paris: on the Right Bank,

the Foire du Trône on the place de la Nation, the Fête à Montmartre, the

Fête des Buttes-Chaumont, the Foire du boulevard de la Villette; and on the

Left Bank, at the place Denfert-Rochereau, the Foire du Lion de Belfort.

55

Smaller versions of the fête foraine were held on a regular basis throughout

Paris. At their prewar height in 1928, some thirty-eight fairs were celebrated

throughout the year, although the next year, in response to growing com-

plaints, the prefecture of police limited the annual calendar to thirteen fairs.

For the first postwar 1946–47 fair cycle, the prefecture of police authorized

thirty-two fairs “to be held at their traditional sites throughout the city,

including the boulevard Saint-Michel.” The number increased to forty-five

in 1948. By 1950 the prefecture of police had authorized fifty-three fairs on

the schedule. The largest number of fairs, nine for the year, each averaging

three weeks in length, was scheduled in the 11th arrondissement. The Fête

de la Bastille, for example, contained more than four hundred stalls.

56

The

inner arrondissements of eastern Paris tended to hold the fairs around the

July 14 national holiday, while the outer arrondissements of the northeast

associated the carnival atmosphere of the fairs with the August commemo-

ration of the Liberation. The fair circuit continued into the working-class

suburbs beyond the city’s borders with, for example, the Fête Foraine des

Quatre Routes, held at the vast intersection in the center of La Courneuve

between 1944 and 1960. No fairs were scheduled for the 1st, 6th, or 8th ar-

rondissements, and only one for the 7th, where “tourists and Parisians who

the landscape of populism | 93

loved the history and stunning panorama of the capital would have consid-

ered a fête foraine on the Esplanade des Invalides a sort of sacrilege.”

57

To take perhaps the best-known example, the Foire du Trône was an

annual post-Lenten celebration shared by all the working-class neighbor-

hoods of the eastern districts.

58

It was integral to “growing up” in and

experiencing the particularity of neighborhood social rites, a passage as-

sociated with folkloric tradition and the carnivalesque frivolity of street

life. The fairs were privileged sites of escape and transgression from the

daily routine of the workplace. In the immediate postwar years, they were

rich with the more complicated meanings of diversion from the war and

its privations and the reemerging vitality of the people. Stretching from the

place de la Nation down the avenue du Trône and up the rue des Pyrénées

to the park at Vincennes, the fair was a month-long carnival of amusement

rides, games, sideshows, and caravans, with their cavalcade of curiosities

and gastronomies. In the years after the war, three different circuses—the

Zanfretta, the Lambert, and the Fanny—lined the avenue du Trône. The

fair celebration and the reenactment of its precise rituals were guarded as

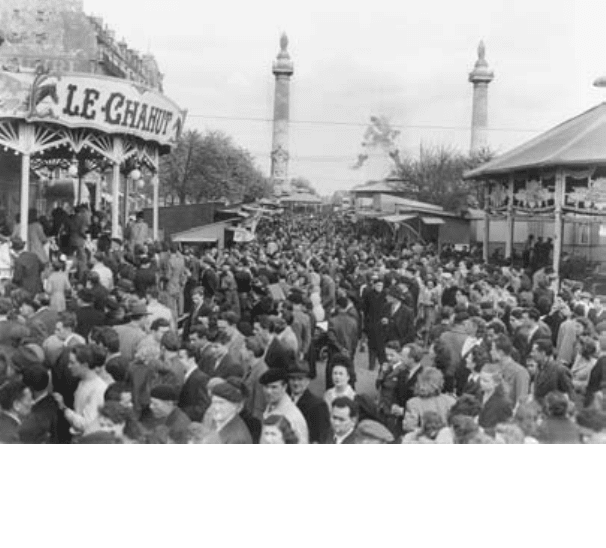

figure 9. The crowd at the Foire du Trône, place de la Nation, March 29, 1948.

© keystone-france.

94 | chapter two

a local entitlement. The crowning of Esmerelda was a custom specific to

the Foire du Trône and was traditionally carried on until 1939 and the war-

time ban. It was revived with the first postwar fair in 1946, when the new

Esmerelda and her cortege of floats and musicians paraded from the place

de la République down the boulevard Beaumarchais, around the place de

la Bastille, up rue du Faubourg Saint-Antoine, and on to the place de la

Nation. These were mammoth public events that swept over neighborhood

space and life. They were a reenactment of the right to the city.

The battles for and against the fêtes foraines were already endless by the

reconstruction years. Although embraced as a symbol of the city’s reemer-

gence, not everyone appreciated the farcical aesthetics and the mobs that

poured into the streets. For some, especially local residents who had to put

up with all the noise and aggravation, they were a public menace. The char-

acter of the fêtes foraines was open-ended, threatening. As the descendants of

Carnival, seen particularly in the seedy ambience that increasingly dominated

their runs, the fairs were signs of inversion, of the grotesque and unseemly—

features that made them suspect for those Parisians interested in questions

of propriety and moral renewal. The music, loudspeakers, amusement rides,

fair booths, and congestion that had in the early twentieth century been

signs of a mesmerizing urban modernity were now an infuriating, infernal

din. An amateur documentary film of the 1954 Foire du Trône captures the

creepy sideshow atmosphere of leering clowns and barkers, cheap rides, and

shooting galleries.

59

The lurid qualities and social mix of the fête foraine in

particular provoked public fears about the savagery and volatility of collective

space. The transient foraine families and the crowds were deemed socially

marginal and dangerous to the community—a breach in the interior quality

of neighborhood space. They were described as a “resounding sham,” “the

plagues of Paris,” and “an intolerable torment.”

60

They threatened public

hygiene and were a menace to traffic. Even neighborhood businesses began

lining up against them for driving away customers. The only arguments in

their favor seemed to be their contribution to the local school budget and

that they were a fairly acceptable hangout for young people.

Despite the criticism, the tradition was not easy to suppress. Populist

images of Paris are filled with renditions of the traveling carnival shows and

their celebratory street atmosphere. In Jacques Prévert’s Parole (1946), the

joyful fun of the fête foraine is spontaneous, vital, a collective merriment that

is the stuff of life:

the landscape of populism | 95

Happy as the trout climbing the torrent

Happy the heart of the world

On its waterspout of blood

Happy the barrel-organ

Bawling in the dust

With its citrus voice

A popular tune

Without rhyme or reason

Happy the lovers

On the Russian mountains

Happy the russet-haired girl

On her white horse

Happy the brown boy

Who waits for her smiling

Happy this man in mourning

Standing in his skiff

Happy the fat dame

With her paper kite

Happy the old fool

Smashing plates. . . .

61

Henri Calet, the chronicler of Paris populaire, captured the spellbinding

pleasures and sheer size of the annual fall Fête du Lion in his Le Tout sur le tout

(1948). The great lion statue on the place Denfert watched over a cavalcade

of traveling entertainers almost every weekend. But the annual fête foraine

was a spectacular affair. A profusion of the strange and bizarre displayed in

sideshow stands mixed with the Folies Cubaines and the Sirènes de Paris,

with their dance of the veils. Entrance marquees titillated fairgoers with ex-

hibitions of the “Human Passions” and the “Debauchery of the Big City.”

Acrobats, fire-eaters, strongmen, and escape artists entertained the crowds.

Miss Liliane performed her snake dance on stage with two lions. The Cirque

Fanny shared the place Denfert with the Grande ménagerie africaine and an

immense boat ride on the site of the present-day RER railway station that

swung fifty screaming people in a high arc above the crowds.

62

In Jacques

Baratier and Jean Valère’s commercially produced documentary film Paris la

nuit (1956), crowds jam a kaleidoscopic fête foraine, wildly enjoying the amuse-

ment rides, midway games, and entertainment. Couples dance the night away