Blank L., Tarquin A. Engineering Economy (McGraw-Hill Series in Industrial Engineering and Management)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

was conducted at a municipal water treatment plant for

evaluating the cost-effectiveness

of

the pre-aeration and

sludge recirculation practices.

Experimental Procedure

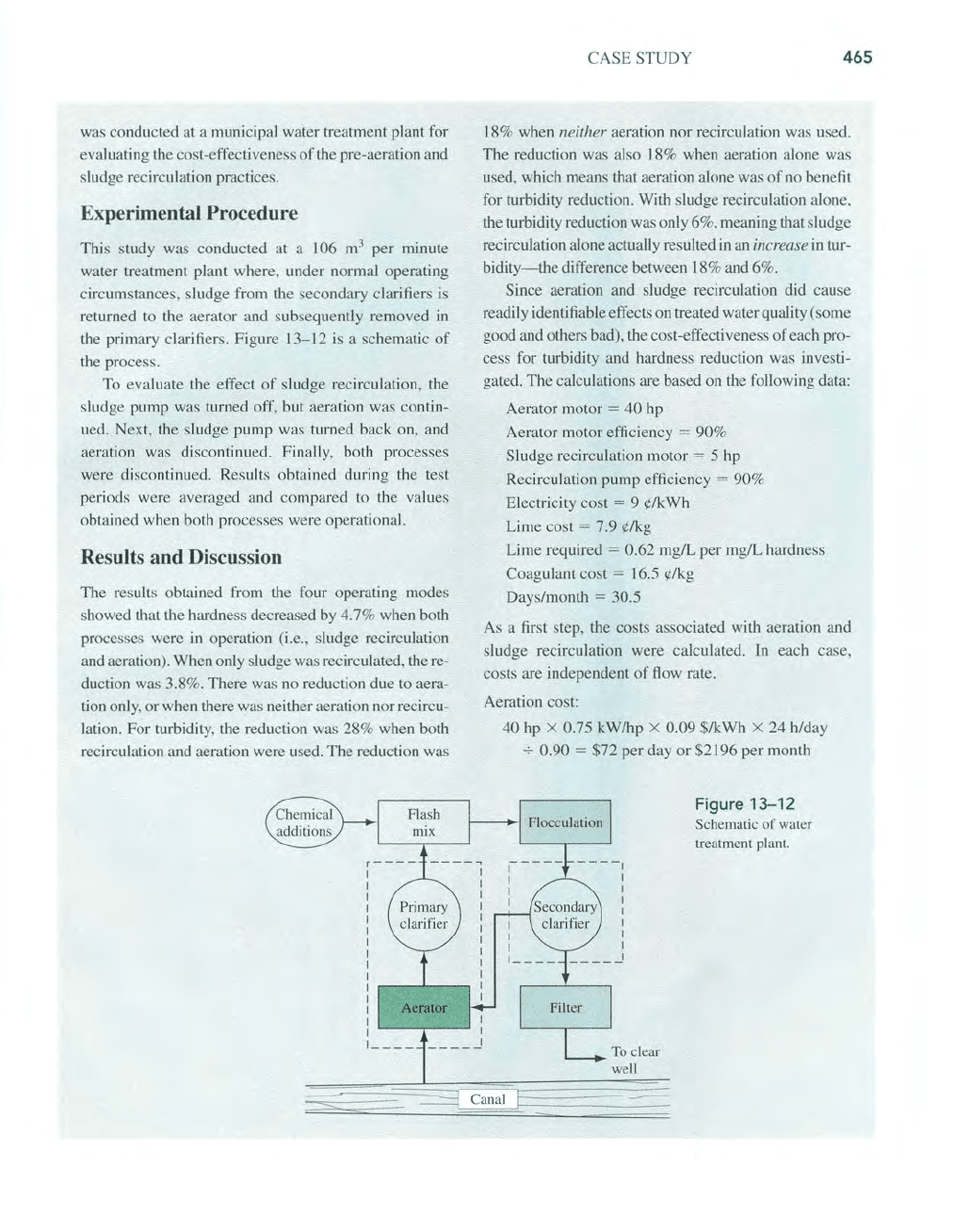

This study was conducted at a

106

m

3

per minute

water treatment plant where, under normal operating

circumstances, sludge from the secondary clarifiers is

returned

to

the aerator and subsequently removed

in

the primary clarifiers. Figure 13-12 is a schematic

of

the process.

To evaluate the effect

of

sludge recirculation, the

sludge pump was turned off, but aeration was contin-

ued. Next, the sludge pump was turned back on, and

aeration was discontinued. Finally, both processes

were discontinued. Results obtained during the test

peri.ods were averaged and compared to the values

obtained when both processes were operational.

Results and Discussion

The results obtained from the four operating modes

showed that the hardness decreased by 4.7% when both

processes were in operation (i.e., sludge recirculation

and aeration). When only sludge was recirculated, the re-

duction was 3.8%. There was

no

reduction due to aera-

tion only, or when there was neither aeration nor recircu-

lation. For turbidity, the reduction was 28% when both

recirculation and aerati

on

were used.

The

reduction was

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

r-

-

.,...L-

_~

1

1

1 1

1 1

L

_______

...I

CASE STUDY

465

18% when neither aeration nor recirculation was used.

The

reduction was also 18% when aeration alone was

used, which means that aeration alone was

of

no

benefit

for turbidity reduction. With sludge recirculation alone,

the turbidity reduction was only 6%, meaning that sludge

recirculation alone actually resulted

in

an

increase

in

tur-

bidity-the

difference between

18

% and 6%.

Since aeration and sludge recirculation did cause

readily identifiable effects on treated water quality (some

good and others bad), the cost-effectiveness

of

each pro-

cess for turbidity and hardness reduction was investi-

gated. The calculations are based on the following data:

Aerator motor

=

40

hp

Aerator motor efficiency

= 90%

Sludge recirculation motor = 5 hp

Recirculation pump efficiency

= 90%

Electricity cost = 9 ¢/kWh

Lime cost

= 7.9 ¢/kg

Lime required

= 0.62 mg/L

per

mg/L hardness

Coagulant cost

= 16.5 ¢/kg

Days/month

= 30.5

As a first step, the costs associated with aeration and

sludge recirculation were calculated.

In

each case,

costs are independent

of

flow rate.

Aeration cost:

40 hp X 0.75 kW/hp X 0.09 $/kWh X 24 h/day

7 0.90 = $72 per day

or

$2196 per month

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1 1

1

________

...I

To clear

well

Figure

13-12

Schematic

of

water

treatment plant.

~

Canal F

~

0-

0-

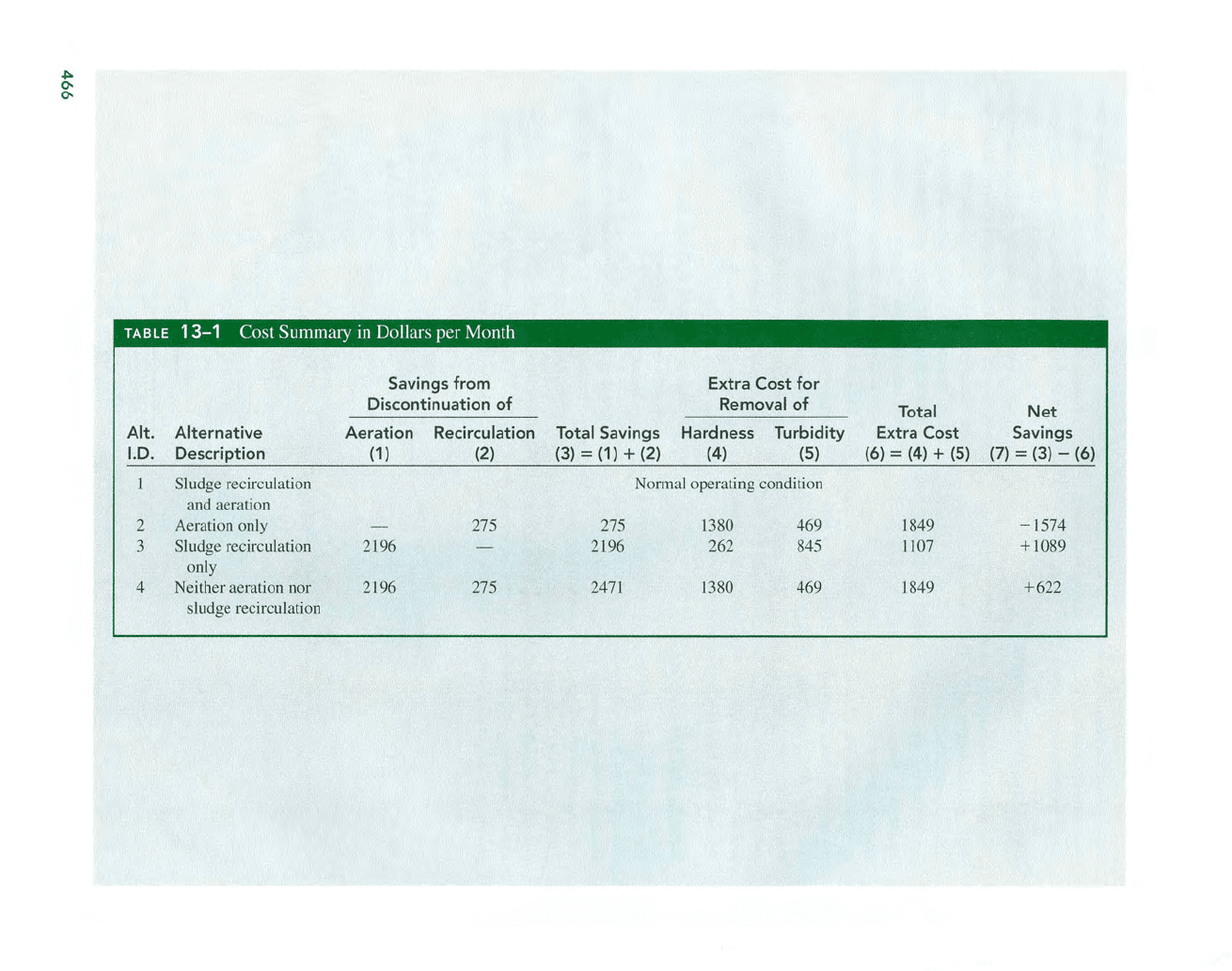

Alt.

1.0.

2

3

4

Alternative

Description

Sludge recirculation

a

nd

aeration

Aeration o

nl

y

Sludge recirculation

o

nl

y

Neither aeration nor

sludge recirculation

Savings from

Discontinuation

of

Aeration Recirculation

(1

) (2)

27

5

21

96

21

96

2

75

Extra Cost

for

Removal

of

Total

Net

Total Savings Hardness Turbidity Extra Cost Savings

(3)

= (1) + (2)

(4) (5)

(6) = (4) + (5)

(7)

= (3) - (6)

Normal opera

ti

ng condition

27

5 1

38

0

4

69

1849 -

1574

21

96

262

845

11

07

+

1089

24

71

13

80

469

1

849

+6

22

S

lu

dge recirc

ul

a

ti

on

cos

t:

5 hp X

0.75

kW/

hp X 0.

09

$/kWh X

24

h/d

ay

-;-

0.90 = $9 per day or $275 per month

The

es

timates app

ea

r

in

columns I and 2 of

th

e cost

summary

in

Table 1

3-

1.

Costs associated with turbidity and hardness re-

m

ova

l are a f

un

c

ti

on

of

the che

mi

cal dosage required

and the wat

er

fl

ow rate.

Th

e

ca

lc

ul

a

ti

ons bel

ow

are

based on a design

fl

ow

of

53 m

3

/minute.

As stated ea

rli

er,

th

ere was less turbidity reduc

ti

on

th

rough

th

e primary cla

ri

fie

r without

ae

ra

ti

on than

th

ere was w

it

h

it

(28%

ve

rsus 6%

).

The extra turbidity

re

aching the

f1

occ

ul

ators could require further additions

of

th

e coag

ul

ating che

mi

cal.

If

it

is assumed that, as a

worst case, these chemical additions would be propor-

t

io

nalt

o

th

e extra turbidity,

th

en 22 per

ce

nt more

co

ag-

ul

ant would be required. Since

th

e average dosage

before

di

scontinua

ti

on

of

aera

ti

on was

10

m

g/

L, the

in

cremen

ta

l chemical cost

in

curred because of

th

e

in

creased turbidity in

th

e clarifi

er

e

fflu

ent would be

(lO X 0.22) mg/L X

1O

-

6

kglmg X 53 m

3

hn

in

X 1

000

Lim

3

X 0. 165 $/kg X

60

min/h

X 24 h/day

=

$27.

70/d

ay

or

$845/

month

S

im

ilar calc

ul

ations

fo

r the other operat

in

g conditions

(i.e.,

ae

ra

ti

on o

nl

y,

and neither aera

ti

on nor slud

ge

re-

circ

ul

a

ti

on) reveal that

th

e additional cost for turbidity

removal wo

ul

d be $469 per month

in

each case, as

shown

in

column 5

of

Ta

bl

e 1

3-1.

Changes

in

hardness affect che

mi

cal costs by virtue

of

the dir

ec

t effect on

th

e amount of lime required for

water so

ft

enin

g.

With aeration and sludge recirc

ul

a-

ti

on,

th

e average hardness reduc

ti

on was 12

.1

mg

/L

(

th

at i

s,

258 mg/L X 4.7 percent

).

However, with

slud

ge

recirculation only,

th

e reduc

ti

on was 9.8 mg/L ,

resulting

in

a difference of 2.3 mg/L attributed to a

era

-

ti

on. The extra cost a

flim

e

in

curred b

eca

use of

th

e dis-

co

ntinua

ti

on of

ae

ration, therefore, was

2.3 mg/L X 0.62 mg/L lime X

1O

-

6

k

g/

mg

X 53 m

3

/min X 1000 Lim

3

X 0.079 $

/k

g

X 60 m

in

/h X

24

h/day = $8.60/d

ay

or

$262/month

When s

lu

dge recirc

ul

a

ti

on was discontinued,

th

ere

was no hardness reduc

ti

on through

th

e cla

ri

fie

I'

, so tbat

the extra lime cost would be

$ 1380 per month.

CASE

STUDY

467

The total savings and t

ota

l costs associated with

changes

in

pl

ant operating conditions are tab

ul

ated in

columns 3 a

nd

6

of

Ta

bl

e 1

3-

1, resp

ec

tivel

y,

with

th

e net

sav

in

gs shown

in

column 7. Obviousl

y,

the optimum

condition is represented by

"s

ludge recirc

ul

a

ti

on o

nl

y."

This condition would result

in

a net sav

in

gs

of$

1 089 per

month,

compa

red to a net sav

in

gs

of

$622 per month

when b

ot

h processes are

di

scontinued and a net cost

of

$

15

74

per month for

ae

ra

ti

on only. Sin

ce

th

e calc

ul

a-

ti

ons made here repr

ese

nt w

or

st-case condition

s,

the

actual savings that resulted from modify

in

g

th

e

pl

ant

operating procedures were greater than those

in

di

ca

ted.

fn

summa

ry

, the

co

mmonly applied wat

er

tr

ea

tm

ent

prac

ti

ces

of

sludge recirc

ul

ation and

ae

ration can sig

ni

f-

icantly

aFf

ec

t

th

e removal

of

some compounds

in

th

e

pri mary cla

ri

f

ie

r.

However, increasing energy a

nd

chem-

ical costs warra

nt

continued investigations on a case-by-

case basis of

th

e cost-effectiveness of such prac

ti

ces.

Case Study Exercises

I. What would be the monthly sav

in

gs

in

electricity

from discontinua

ti

on of aeration if

th

e cost

of

electricity were 6 ¢/kWh?

2. Does a d

ec

r

ease

in

the e

ffi

ciency of

th

e

ae

rator

motor make the sel

ec

ted

al

te

rn

a

ti

ve

of

slud

ge

recircula

ti

on o

nl

y more attr

ac

ti

ve, less attractive,

or the same as b

efo

re?

3.

If the cost of lime were to increase by

50

%,

would

th

e cost

di

fferen

ce

between the best alter-

na

ti

ve and second-best alterna

ti

ve

in

crease, de-

crease, or rema

in

the sam

e?

4. ff

th

e e

ffi

ciency

of

th

e slud

ge

recirc

ul

a

ti

on pump

were reduced

fr

om

90

% to

70

%, would

th

e net

savings

dif

fe

rence between alternatives 3 and 4

increase, decrease,

or

stay the

same

?

5. If hardness removal were to be

di

scontinued at

the treatment

pl

ant, which alterna

ti

ve would be

the most cost

-e

f

fec

ti

ve?

6. If the cost of el

ec

tricity d

ec

r

ease

d to 4 ¢/kWh,

w

hi

ch a

lt

erna

ti

ve

wo

uld be the most cost-

ef

fec

ti

ve?

7. At what electricity cost

wo

ul

d the fo

ll

ow

in

g

alte

rn

a

ti

ves

ju

st break eve

n:

(a) alte

rn

a

ti

ves I and

2, (b) a

lt

e

rn

atives I and 3, (c) alternatives I a

nd

4?

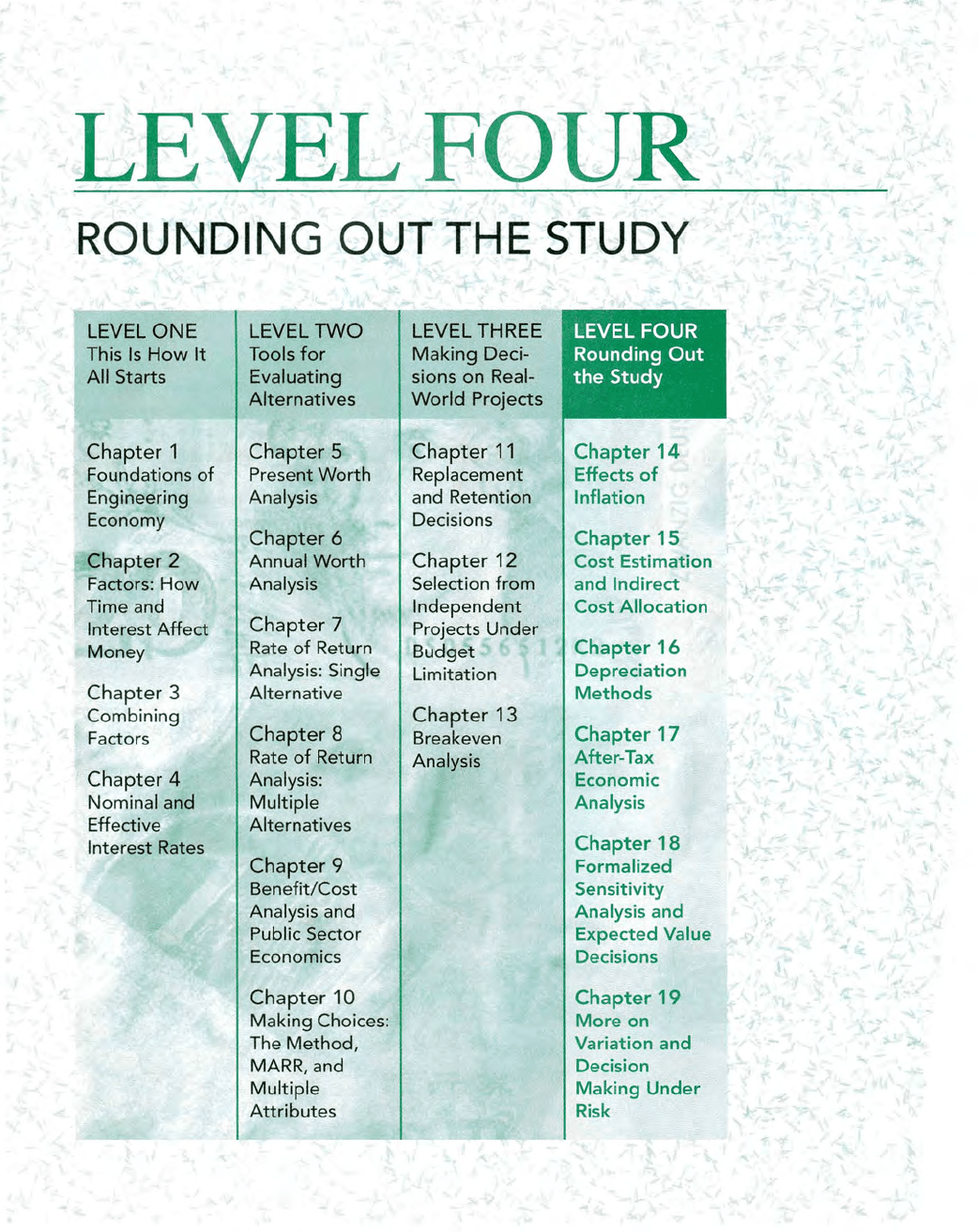

LE

V

EL

FOUR

ROUNDING OUT THE STUDY

LEVEL

ONE

This

Is

How

It

All Starts

Chapter

1

Foundations

of

Engineering

Economy

Chapter

2

Factors:

How

Time and

Interest

Affect

Money

Chapter

3

Combining

Factors

Chapter

4

Nominal and

Effective

Interest Rates

LEVEL

TWO

Tools

for

Evaluating

Alternatives

Chapter

5

Present Worth

Analysis

Chapter

6

Annual Worth

Analysis

Chapter

7

Rate

of

Return

Analysis: Single

Alternative

Chapter

8

Rate

of

Return

Analysis:

Multiple

Alternatives

Chapter

9

Benefit/Cost

Analysis and

Public Sector

Economics

Chapter

10

Making Choices:

The

Method,

MARR, and

Multiple

Attributes

LEVEL

THREE

Making

Deci-

sions

on

Real-

World

Projects

Chapter

11

Replacement

and Retention

Decisions

Chapter

12

Selection

from

Independent

Projects Under

Budget

Limitation

Chapter

13

Breakeven

Analysis

LEVEL

FOUR

Rounding

Out

the

Study

Chapter

14

Effects

of

Inflation

Chapter

15

Cost Estimation

and

Indirect

Cost

Allocation

Chapter

16

Depreciat

ion

Methods

Chapter

17

After-Tax

Economic

Analysis

Chapter

18

Formalized

Sensitivity

Analysis and

Expected Value

Decisions

Chapter

19

More

on

Variation and

Decision

Making

Under

Risk

This level i

ncludes

topics

to

enhance

your

ab

ility

to

perform

a

th

oroug

h

e

ngin

eer

ing

econom

ic

study

of

one

or

more alternatives. The effects of

inflation,

depreciation,

in

come

taxes

in

all

types

of

studies, and

indirect

costs

are in

corporated

i

nto

the

methods

of

previous

chapters. Several

tec

hniqu

es

of

cost

estimation

to

better

predict

cash flows are

treated

in ord

er

to

base

alternative

selection on

more

accurate estima

te

s.

The

last

two

chapters

include

additio

nal material

on

the

use

of

engi

neering

economics

in

decision

making.

An

expande

d version

of

sensitiv

ity

analysis

is

developed;

it

formal-

izes

the

a

ppro

ach

to

examine

parameters

that

vary

over

a

predictable

range

of

values. Finally,

the

el

ements

of

risk and

probab

ility are ex

plicitly

consid-

ered

u

si

ng

expected

va

lu

es,

probabilistic

analysis, and

Monte

Carlo-based

comp

ut

er

simulation.

Several

of

these

topics can

be

covered

earlier

in

the

text,

depending

on

the

objectives

of

the

course. Use

the

chart

in

the

Preface

to

deter-

mine

appropriate

points

at

which

to

introduce

the

material.

....

14

UJ

I-

a...

I

u

Effects

of

Inflation

This

chapte

r

co

ncen

tr

ates

upon

understanding

and

ca

lculating

the

effects

of

inf

l

ation

in

time

value

of

money

computa

tions

. Inflation

is

a reality

that

we

deal

with nearly

everyday

in professional

and

personal life.

The

annual

inflation

rate

is

closely

watched

and historically analyzed

by

government

units, businesses,

and

industrial

corporations.

An

engi

neering

eco

nomy

s

tudy

can have

different

outcomes

in

an

environment

in

which infla-

tion

is

a serious

co

ncern

compared

to

one

in which

it

is

of

minor

considera-

tion

.

In

the

last f

ew

years

of

the

20th

century,

and

the

beginning

of

the

21

st

century,

inflation

has

not

been

a

major

concern in

the

U.S.

or

most

i

nd

ustri-

alized nations.

Bu

t

the

inflati

on

rate

is

sensitive

to

real,

as

we

ll

as

perceived,

factors

of

the

economy

. Factors such

as

the

cost

of

energy

,

int

erest rates,

availabi

lit

y

and

cost

of

skilled

people,

sca

rcity

of

materials,

politi

ca

l st

ab

ility,

and o

th

e

r,

less

tangible

factors have short

-t

erm

and

long-term

impacts

on

the

infl

at

ion rate.

In

so

me

industries,

it

is vital

that

th

e effects of inflation

be

integrated

into an

econom

ic analysis.

The

basic

techniques

to

do

so are

covered

here.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Purpose: Consider inflation

in

an

engineering economy analysis.

Impact of inflation

PW with inflation

FW with inflation

AW with inflation

This

chapter

will

help

you:

1.

Determine

the

difference

inflation

makes

between

money

now

and

money

in

the

future.

2.

Calculate

present

worth

with

an

adjustment

for

inflation.

3.

Determine

the

real

interest

rate

and

calculate

a

future

worth

with

an

adjustment

for

inflation.

4.

Calculate

an annual

amount

in

future

dollars

that

is

equivalent

to

a

specified

present

or

future

sum.

472

CHAPTER

14

Effects

of

Inflation

14.1 UNDERSTANDING THE IMPACT OF INFLATION

We are all very well aware that $20 now does not purchase the same amount

as

$20

did

in

1995

or

1996 and purchases significantly less than in 1980. Why?

Primarily because

of

inflation.

Inflation

is

an

increase in

the

amount

of

money necessary to obtain the

same

amount

of

product

or

service before the inflated price was present.

Inflation occurs because the value

of

the currency has

changed-it

has gone

down

in

value.

The

value

of

money has decreased, and as a result, it takes more

dollars for the same

amount

of

goods

or

services. This is a sign

of

inflation. To

make comparisons between monetary amounts

which

occur

in

different time pe-

riods, the different-valued dollars must first be converted to constant-value dol-

lars

in

order to represent the

same

purchasing

power

over time. This is especially

important when future sums

of

money are considered, as

is

the case with all al-

ternative evaluations.

Money

in

one

period

of

time

tl

can be brought to the same value as money

in

another period

of

time

t2

by using the equation

D

11

. . d dollars

in

period f?

oars

111

peno

fl = -

inflation rate between

fl

and t2

[14.1 ]

Dollars

in

period

tl

are called constant-value dollars

or

today's dollars. Dollars

in

period

t2

are called future dollars

or

then-current dollars.

Iff

represents the i n-

flation rate per period (year) and n is the number

of

time periods (years) between

II

and f

2

,

Equation [14.1] is

future

dollars

Constant-value dollars

=

today's

dollars =

(1

+

f)"

[14.2]

Future

dollars =

today's

dollars(1 +

f)"

[14.3]

It

is

correct to express future (inflated) dollars

in

terms

of

constant-value dol-

lars, and vice versa, by applying the last two equations. This is how the

Consumer

Price Index (CPI) and

cost

estimation indices

(of

the next chapter) are determined.

As an illu

st

ration, use the price

of

a

McDonald'

s Big

Mac

in

some parts

of

Texa

s.

$2.23 August 2004

If

inflation averaged 4% during the last year,

in

constant-value 2003 dollars, this

cost

is

last

year's

equivalent

of

$2.23/(

1.04) = $2.14 August 2003

A predicted price

in

2005 is

$2.23(1.04)

= $2.32

August

2005

If inflation averages 4% per year over the next 10 years, Equation [14.3]

is

used

to predict a

Big

Mac

price

in

2014:

$2.23(1.04)10

= $3.30

August

2014

SECTION 1

4.

1

Understanding

the

Impa

ct

of

Inflation

This

is

a 48% increase

over

the 2004 price at 4% inflation, which is considered

low to average nationally and internationally.

If

inflation averages

6%

per

year, the

Big

Mac

cost

in

10 years will be $3.99, an increase

of

79

%.

In

some

areas

of

the world, hyperinflation may average

50

% per year. In such an un-

fortunate economy, the Big Mac

in

LO

years rises from the dollar equivalent

of

$2.23 to $128.59! This is why countries experiencing hyperinflation must de-

value the currency by factors

of

100 and 1000 when unacceptable inflation

rates persist.

Placed into

an

industrial

or

business context, at a reasonably low inflation

rate avera

gi

ng 4% per year, equipment

or

services with a first cost

of

$209,000

will

in

crease by 48% to $309,000 over a lO-year span. This is before any consid-

eration

of

the rate

of

return requirement is placed upon the equipment's revenue-

generating ab

ili

ty. Make no mistake: Inflation is a formidable force in our

econom

y.

There are actually three different rates that are important: the real interest rate

(i), the market interest rate

(if)'

and the inflation rate

(f)

. Only the first two are

interest rate

s.

Real

or

inflation-free interest

rate

i. This is the rate

at

which interest is

ea

rn

ed when the effects

of

changes

in

the value

of

currency (inflation) have

been removed. Thus,

th

e real interest rate presents an actual gain in pur-

chasing power. (The equation used to calculate

i,

with the influence

of

inflation removed, is derived later

in

Section 14.3.) The real rate

of

return

th

at genera

ll

y applies for individuals is approximately 3.5% per year. This is

th

e

"s

afe investment" rate. The required real rate for corporations (and many

individuals) is set above thjs safe rate when a

MARR

is established without

an

adjustment for inflation.

Inflation-adjusted interest

rate

ir

As its name implies, this

is

the interest

rate that has been ad

ju

sted to take inflation into account.

The

market inter-

est rate, w

hi

ch is the one we hear everyday, is an inflation-adjusted rate.

This rate

is

a combination

of

the real interest rate i and the inflation rate

f,

and, therefore, it changes as the inflation rate changes. It

is

also known as

the

in

flated interest rate.

Inflation

ratef.

As described above, thjs is a measure

of

the rate

of

change

in

the va

lu

e

of

the currency.

A company's

MARR

adjusted for inflation is referred to as the inflation-adjusted

MARR. The determination

of

this value is discussed in Section 14.3.

Deflation

is

the opposite

of

inflation

in

that when deflation is present, the pur-

chas

in

g power

of

the monetary unit is great

er

in the future than at presen

t.

That

is

, it w

ill

take fewer dollars

in

the future to buy the sa

me

amount

of

goods

or

ser-

vices as

it

does today. Inflation occurs much more commonly than deflation,

especially at the national economy level. In deflationary economic conditions,

the market interest rate is always less than the real interest rate.

Temporary price deflation may occur

in

spe

cific sectors

of

the economy due to

the introduction

of

improved products, cheaper technology,

or

imported materials

or products that force currenl prices down. In normal situations, prices equalize

at

473

Safe investme

nt:

rate

474

CHAPTER

14

Effects

of

Inflation

a competitive level after a short time. However, deflation over a short time in a

specific sector

of

an economy can be orchestrated through dumping. An example

of

dumping may be the importation

of

materials, such as steel, cement, or cars,

into one country from international competitors at very low prices compared to

current market prices in the targeted country. The prices will go down for the con-

sumer, thus forcing domestic manufacturers to reduce their prices in order to

compete for business.

If

domestic manufacturers are not in good financial condi-

tion, they may fail, and the imported items replace the domestic supply. Prices

may then return to normal levels and, in fact, become inflated over time,

if

com-

petition has been significantly reduced.

On the surface, having a moderate rate

of

deflation sounds good when infla-

tion has been present

in

the economy over long periods. However,

if

deflation

occurs at a more general level, say nationally, it is likely to be accompanied by

the lack

of

money for new capital. Another result is that individuals and families

have less money to spend due to fewer jobs, less credit, and fewer loans avail-

able; an overall "tighter" money situation prevails.

As

money gets tighter, less

is

available to be committed to industrial growth and capital investment.

In

the ex-

treme case, this can evolve over time into a deflationary spiral that disrupts the

entire economy. This has happened on occasion, notably in the United States dur-

ing the Great Depression

of

the 1930s.

Engineering economy computations that consider deflation use the same rela-

tions as those for inflation. For basic equivalence between today's dollars and fu-

ture dollars, Equations [14.2] and [14.3] are used, except the deflation rate is a

-f

value. For example,

if

deflation is estimated to be 2% per year, an asset that

costs

$10,000 today would have a first cost 5 years from now determined by

Equation [14.3].

10,000(1 -

f)"

= 10,000(0.98)5 = 10,000(0.9039) = $9039

14

.2 PRESENT WORTH CALCULATIONS

ADJUSTED FOR INFLATION

When the dollar amounts

in

different time periods are expressed in constant-

value dollars,

the equivalent present and future amounts are determined using

the real interest rate

i.

The calculations involved in this procedure are illus-

trated

in

Table 14-1 where the inflation rate is 4% per year. Column 2 shows the

inflation-driven increase for each

of

the next 4 years for an item that has a cost

of

$5000 today. Column 3 shows the cost in future dollars, and column 4 veri-

fies the cost in constant-value dollars via Equation [14.2]. When the future dol-

lars

of

column 3 are converted to constant-value dollars (column 4), the cost is

always

$5000, the same as the cost at the start. This is predictably true when the

costs are increasing by an amount

exactly equal to the inflation rate. The actual

(inflation-adjusted) cost

of

the item 4 years from now will be $5849, but in

constant-value dollars the cost in 4 years will still amount to

$5000. Column 5