Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

centrate on the diplomatic and supervisory functions it performed well. The

shift (especially after ) to national government finance and administration

for universal provision of minimum standards of relief from poverty and of

medical care in hospitals and by general practitioners left local government to

concentrate on education, housing and other functions that appeared at the time

better suited to the structure of local authorities. Crucial to this shift, as Martin

Daunton argues, was the ability of the national government to increase revenue

through income tax. The changing balance was an uneven process, far from

inevitable, fraught with tensions and conflicts, marked by collaboration, changes

in the sectors and losses as well as gains. The poor law guardians, for example,

increasingly marginalised in the provision of urban social welfare, gave way in

to large local government committees and eventually the central govern-

ment at the cost of a loss of local, democratic accountability and opportunities

for local influence on the levels and conditions of relief payments.

146

Similarly,

the decline of friendly societies is linked to a loss of local influence over indi-

vidual health care, though their coverage was far from universal. The national

insurance legislation of created a partnership between the central govern-

ment and commercial insurance companies which was dissolved by the national

insurance legislation of with each going a separate way. Meanwhile, the

central government absorbed, under the appointed, nationally financed regional

hospital boards of the NHS, the voluntary and local authority hospitals which

ran in parallel and often in competition in the s.

147

Yet, even after at the height of central government provision of social ser-

vices for the relief of poverty and medical care, voluntarism and local authorities

were not a by-product but an integral part of the contemporary concept of the

welfare state.

148

Since then the balance has changed: rather than coming under

local government, the NHS and the provision of health care became further

removed from local government by the abolition of the medical officers of health

in , and from the s there has been growing emphasis on the provision

of social welfare by the voluntary and commercial sectors. Nevertheless, within

these overall changes in the balance of the welfare mix, variations in the source

and, to some extent, in the level of provision among individual urban areas

remain. Different locations within the urban hierarchy can make a difference.

Urban history still matters, even in the provision of those social welfare services,

earliest and least controversially transferred to central government.

Marguerite Dupree

146

Vincent, Poor Citizens, pp. –; Daunton, ‘Payment and participation’, ‒.

147

Finlayson, ‘Moving frontier’; C. Webster, ‘Labour and the origins of the National Health

Service’, in N. Rupke, ed., Science, Politics and the Public Good: Essays in Honour of Margaret Gowing

(London and Basingstoke, ), pp. –.

148

W. Beveridge, Voluntary Action: A Report on Methods of Social Advance (London, ); Finlayson,

Citizen, State and Social Welfare, pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

·

·

Structure, culture and society in British towns

. .

A

start of the period covered by this volume, two men wrote about

social relationships in British towns in very different ways. Thomas

Chalmers was a Scottish minister of religion.

1

He spent much energy

trying to reconcile political economy and evangelical religion. In , he wrote:

In a provincial capital, the great mass of the population are retained in kindly and

immediate dependence on the wealthy residents of the place. It is the resort of

annuitants, and landed proprietors, and members of the law, and other learned pro-

fessions, who give impulse to a great amount of domestic industry, by their expen-

diture; and, on inquiry into the sources of maintenance and employment for the

labouring classes there, it will be found they are chiefly engaged in the immediate

service of ministering to the wants and luxuries of the higher classes in the city.

This brings the two extreme orders of society into that sort of relationship which

is highly favourable to the general blandness and tranquillity of the whole popu-

lation. In a manufacturing town on the other hand, the poor and the wealthy stand

more disjointed from each other. It is true they often meet, but they meet more

on an arena of contest, than on a field where the patronage and custom of the one

party are met by the gratitude and good will of the other. When a rich customer

calls a workman into his presence, for the purpose of giving him some employ-

ment connected with his own personal accommodation, the general feeling of the

later must be altogether different from what it would be, were he called into the

presence of a trading capitalist, for the purpose of cheapening his work, and being

dismissed for another, should there not be an agreement in their terms.

2

His own experience was in Edinburgh and Glasgow but equally he saw a con-

trast between places like Oxford and Bath on the one hand and manufacturing

1

Rev. William Hanna, Memoirs of Thomas Chalmers, D.D. LL.D., vols. (Edinburgh, ); Stewart

J. Brown, Thomas Chalmers and the Godly Commonwealth in Scotland (Oxford, ); Stewart J.

Brown and Michael Fry, eds., Scotland in the Age of the Disruption (Edinburgh, ).

2

T. Chalmers, The Christian and Civic Economy of Large Towns, vol. (Edinburgh, –), pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

cities like Leeds and Manchester on the other. For Chalmers, towns with

different economic and social structures produced very different sorts of social

relationships. In other words, specific economic structures, market relationships

as well as relationships of production, provided the explanation or at least created

conditions for different cultural outcomes. Chalmers’ work was driven by

anxiety over religious observance, pauperism and disorder. He saw the town as

a place of problems created by these new conditions but problems for which

thinking and moral men could provide solutions.

Robert Vaughan was very different, a dissenting minister from the West of

England, an intellectual of the Congregational Union. In The Age of Great Cities,

published in , he defended cities as places of freedom and progress, part of

‘the struggle between the feudal and the civic’.

3

He had very clear ideas as to

why this should be so. He regarded the spread of knowledge as crucial for

freedom. Cities were part of this as they provided conditions for the creation of

an active press and publication by ‘large sales and small profits’.

4

Art and science

flourished in the cities because they were places of ‘ceaseless action . . . [and] . . .

accumulation’ which provided resources for ‘minds capable of excelling in

abstract studies’. He recognised that the ‘more constant and more varied associ-

ation into which men are brought by means of great cities tends necessarily to

impart greater knowledge, acuteness and power to the mind than . . . a rural

parish’.

5

The urban labour market was another source of freedom as ‘the poor

are little dependent on the rich, the employed are little dependent on their

employers’.

6

It was not just that Vaughan was more optimistic than Chalmers

about urban life, but his whole structure of argument differed. Vaughan looked

to something which a later generation of sociologists would call an ‘urban way

of life’ and derived from this a whole set of social relationships.

7

Urban in the

generic sense created the conditions for freedom, choice, wealth and progress.

Although he recognised class conflict and the inequalities of wealth, Vaughan’s

ideal was a society of rational, knowledgeable individuals not a society of hier-

archies. The inequalities of feudalism and class would be reduced by the working

of the intelligence and association of the city. The urban created relationships

now identified with modernity.

8

These two attempts to explain and understand what was happening in British

towns contained elements of a wider and continuing debate on the nature and

relationship of social structure and culture in British towns. Although definitions

R. J. Morris

3

Robert Vaughan, TheAge of Great Cities (London, ), p. .

4

Ibid.,p..

5

Ibid.,p..

6

Ibid., p. .

7

Louis Wirth, ‘Urbanism as a way of life’, in Louis Wirth, On Cities and Social Life, ed. Albert J.

Reiss, jr. (Chicago, ).

8

M. Savage and A. Warde, Urban Sociology, Capitalism and Modernity (Basingstoke, ); Gunther

Barth, City People:The Rise of Modern City Culture in Nineteenth Century America (Oxford, );

M. Berman, All That Is Solid Melts into Air (New York, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

are contested they must be attempted. Social structures are perceived regularities

of social behaviour and characteristics identified by relevant social actors or by

the observer analyst. These structures are orderly, patterned and persistent.

Those selected for comment and analysis are those judged to be important in the

explanation of action, experience and change.

9

In the European literature of the

last two hundred years, structures involved in the material relationships of pro-

duction have been given especial attention but attention has rapidly extended to

relationships of reproduction and association such as gender, family and the

urban. The identification of social structures is important because of their place

in explanation.

10

Few studies consider that historical actions and change were

determined by key structures but many do see structure as one of several

influences. Indeed, the influence of structure in these accounts may go beyond

the meanings attributed to them and work in ways not perceived by historical

actors.

11

One theoretical extreme questions the knowability of social structure.

After all, the evidence from which such structures were deduced were them-

selves cultural products, but the task of inferring structures remains a matter of

self-conscious historical and analytical judgement. Perhaps most common is the

view that structure, especially those related to material production, set broad

limits within which human agency could act and react.

12

In explanations of the nature of experience in British towns, human agency

operated not just to produce specific actions but in the creation of culture. That

culture may be defined as the series of meanings which human beings attrib-

uted to actions, objects, to other people over the whole range of practice from

religion to politics, production and consumption.

13

Cultural resources guide

action by providing boundaries, legitimacy and motivations as well as by

opening up possibilities. Causal relationships are contested. A simplistic and

rarely presented view might consider culture as a product of structure, especially

economic structure. More common is the view that culture is influenced by

structure. Thus the wage labour of large factories makes class-conscious politics

possible but was in no way asufficient ‘cause’. The perspective which regards

culture as an autonomous element in any historical situation is especially impor-

tant for urban historians as urban cultures not only build upon the resources

inherited from their own past but also import and select cultural elements from

Structure, culture and society in British towns

19

Joseph Melling and Jonathan Barry, eds., Culture in History: Production, Consumption and Values in

Historical Perspective (Exeter, ); Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann, The Social Construction

of Reality (London, ); John Rex, Key Problems in Sociological Theory (London, ).

10

Melling and Barry, Culture in History, especially introduction and essays by Stephen Mennell and

Iain Hampsher Monk, pp. –.

11

A. Giddens, The Constitution of Society (Cambridge, ), pp. –, –.

12

Raymond Williams, Problems in Materialism and Culture (London, ), pp. –

13

Clifford Geertz, ‘Religion as a cultural system’, in Michael Banton, ed., Anthropological Approaches

to the Study of Religion (London, ), pp. –; M. Douglas and B. Isherwood, The World of Goods

(London, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

national and international culture. Mendelssohn’s Elijah came to the Birming-

ham Music Festival in because the middle-class elite of that city wanted

to take part in the broad stream of European culture not because of the small

workshop nature of production or even the rapidly changing nature of the

market in that city.

14

Within the debate remains an interest in long-term social processes. Did the

spread and intensification of capitalist relationships create certain types of

conflict and social identity? Is there a long-term process of ‘civilisation’ in which

perhaps towns and cities are implicated? Do the social and cultural processes of

modernity exist in which the accumulation of wealth and knowledge leads to a

rational individualistic society? How far do traditions of law, market relationships

and certain types of institutional practice produce a ‘civil society’?

15

This debate over structure and culture matters for several reasons. Culture

includes the many processes that give meanings. These meanings have agency.

They promote individual actions. They are the basis on which identities are

created and mobilised. The attention given to structure derives from the feeling

that it matters if a town depends on wage labour working in large units of pro-

duction, rather than casual labour on uncertain and low wages. This attention

derived from the belief that social relationships were influenced by the fact that

a town derived its income from the pensions and rentier incomes of retired males

or unmarried females rather than from an elite of merchants and manufacturers

employing wage labour. These structures were related to different social

situations.

Under the conditions of industrial capitalism selling to ‘distant markets’ the

city, the town, the urban place was the site where the processes that link culture

and structure were interacting in the clearest and strongest ways. In a true sense

the city was the frontier of capitalism and modernity. Capitalism, that is a system

of social and economic relationships defined by private ownership, the search

for profits and a cash economy, was linked to modernity, a system defined by

the accumulation of knowledge, rationality and the division of public and

private in human actions and feelings. The city itself was one product of this

interaction. The city was both a structure and a cultural product.

16

Once created

in both its material and cultural sense, the city became an object of contest

within the middle class, between classes and between self-aware interest groups

R. J. Morris

14

R. J. Morris, ‘Middle-class culture, –’, in D. Fraser, ed., A History of Modern Leeds

(Manchester, ).

15

Norbert Elias, The Civilizing Process (Oxford, ), originally published ; J. A. Hall, ed.,

Civil Society (Cambridge, ); Robert D. Putnam, Making Democracy Work (Princeton, );

Savage and Warde, Urban Sociology.

16

R. J. Morris, ‘The middle class and British towns and cities of the Industrial Revolution,

–’, in D. Fraser and A. Sutcliffe, eds., The Pursuit of Urban History (London, ), pp.

–.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

around which other identities and realised structures were formed. In the minds

of those involved the town itself became an ‘actor’. It was reified and people

reacted to the relationships of the towns and the perceived realities of social

structure.

17

The interest in the relationship between urban culture and the economic and

social structure of British towns was and is part of a wider inquiry into the nature

of the British response to industrial change. It was part of a desire to understand

the long-term stability of British society coupled with the persistence of class-

based conflicts of industrial and urban change.

18

Before going further, a warning.

This section is not just about what happened in British towns and cities, it is

about a debate, an argument, a search for understandings. Because of this the

section must be read at two levels. It is about the social processes and experiences

of these towns and cities. It is about what actually happened. It is also an account

of the way in which historians and contemporaries have tried to understand

what was happening. Before the mid-s, historians gave central place to the

politics, and to the relationships, consciousness and culture of social class. From

the late s, this emphasis was being supplemented by the identities and struc-

tures of gender and those of nationalism, religion and ethnicity. At the same time

there was a growing awareness of the independent generation of culture and its

powerful agency in the direction of human conduct. This was accompanied by

a less intense debate which questioned the clarity and validity of the urban–rural

dichotomy, the integrity of the urban place and even any concept of the urban

itself. History as always is not just an account of the past, it is an account of the

relationship between past and present .

The reluctance of historians to debate the nature of the city or of the urban

as a social structure or as an aspect of culture poses considerable problems for an

inquiry into the relationship between culture and structure in the towns and

cities of Britain. The definition of the urban as a form of human association and

settlement with the properties of size, density and variety is incomplete but

density, especially transactional density, and variety though not ‘causes’ of an

‘urban way of life’ are crucial parameters in urban experience and identities. The

urban place was also a focus for power, a ‘fort’, a ‘market’ and a ‘temple’.

19

In

the nineteenth-century town, the market and its institutions were increasingly

diffuse and pervasive. The castle and the city walls had been replaced by the town

Structure, culture and society in British towns

17

This is in part a response to the warning and challenge of Philip Abrams, ‘Towns and economic

growth: some theories and problems’, in P. Abrams and E. A. Wrigley, eds., Towns in Societies

(Cambridge, ), and R. E. Pahl, Whose City? (London, ), pp. –.

18

R. J. Morris, Class and Class Consciousness in the Industrial Revolution, – (London, );

M. Savage and A. Miles, The Remaking of the British Working Class, – (London, ).

19

Wirth, ‘Urbanism as a way of life’; Max Weber, The City, trans. and ed. Don Martindale and

Gertrud Neuwirth (New York, ); Paul Wheatley, ‘What the greatness of a city is said to be’,

Pacific Viewpoint, (), –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

hall and the local government rate demand. The ‘temple’ no longer had the

mystic of the priest king, but municipal ceremonies, foundation myths and sport

were some of the ways in which the urban places of industrial Britain inspired

loyalty and gave meaning to citizens’ lives.

The Lancashire mill towns were not representative British towns but to his-

torians and contemporaries they represented the leading edge of the fundamen-

tal impact of industrial change.

20

The cotton-spinning town of Oldham in

Lancashire has become a ‘type site’. In mid-century, the social relationships of

Oldham were dominated by a wage relationship in which , wage-earning

families sold their labour to seventy families which gained income from the own-

ership of capital in the cotton-spinning, coal-mining and hatting industries.

21

The outcome was an aggressive radical culture which gained control of key

agencies of local government, the vestry, police and poor law and guided a series

of main force confrontations, notably in the general strikes of and .

This culture was informed by an experience of economic change in which

wages had fallen, income was disrupted by massive fluctuations in demand and

technological change seemed to bring increased inequality and loss of control

for working people. The political debates of this period blamed the ‘oppressive

conduct of capitalists’ and their ‘misapplication of machinery’ and identified

change in the overall system of economic and political arrangements as a solu-

tion.

22

In the s, Manchester, influenced by the large units of production of

the cotton industry, had been unable to sustain a coherent campaign in favour

of parliamentary reform whilst Birmingham, dominated by small workshop pro-

duction, generated the Birmingham Political Union which became a model for

working-class and middle-class cooperation.

23

A generation later the casual

labour market of east London produced a political culture with little formal

organisation but outbreaks of violence which spread to Trafalgar Square and the

West End in and . This brought a broadly based philanthropic response

from the middle classes of the capital.

24

Bath fitted the consumer society which

Chalmers identified as the basis of kindly relationships. In fact the outcome in

the s was an active radical political culture with clear demands for political

change widening the franchise and introducing the secret ballot. Other areas

dominated by skilled labour, notably Edinburgh and parts of south London, were

the base for an assertive radical culture of the skilled male labour force but a

R. J. Morris

20

Friedrich Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England, trans. and ed. W. O. Henderson

and W. H. Chaloner (Oxford, ); Sir George Head, Home Tour through the Manufacturing Districts

of England in the Summer of (London, ).

21

J. Foster, ‘Nineteenth-century towns – a class dimension’, in H. J. Dyos, ed., The Study of Urban

History (London, ), pp. –.

22

J. Foster, Class Struggle and the Industrial Revolution (London, ), pp. –.

23

A. Briggs, Victorian Cities (London, ), pp. –; Asa Briggs, ‘The background of the parlia-

mentary reform movement in three English cities (–)’, Cambridge Historical Journal,

(–), –.

24

G. Stedman Jones, Outcast London (Oxford, ), pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

culture which was prepared to bargain with the agencies of middle-class and elite

power.

25

Further inquiry added increasing layers of complexity to the initial account.

The nature of local leadership was crucial. The Birmingham banker, Thomas

Attwood, was influential in the creation of the consensus which was the basis of

the Birmingham Political Union and in sustaining this consensus through several

conflict-ridden years. Equally, elements of recent history and historical memory

were important. In Manchester memories of Peterloo were a major barrier to

cooperation. In , a radical demonstration had been violently broken up by

volunteer yeomanry closely identified with the local middle classes. A compari-

son of Oldham with other Lancashire mill towns reduced the importance of the

large technologically advanced factory as a basis for explanation. In , the

number of workers per firm in the cotton textile industry of Oldham was , well

below Blackburn (), Manchester () and Ashton ().

26

In Birmingham

any consensus relationship derived from the experience of small workshops

rapidly deteriorated in the s and s under the impact of competition from

a very few large units and the control of the market by merchants.

27

Manchester

was as much a place of warehouses, banks and shops as it was of factories. Factories

were only one aspect of the economic power of a middle-class elite of substan-

tial employers, merchants and professionals. They were linked to the urban by the

local land and labour markets, by an increasingly complex infrastructure and by

an increasingly focused urban government.

28

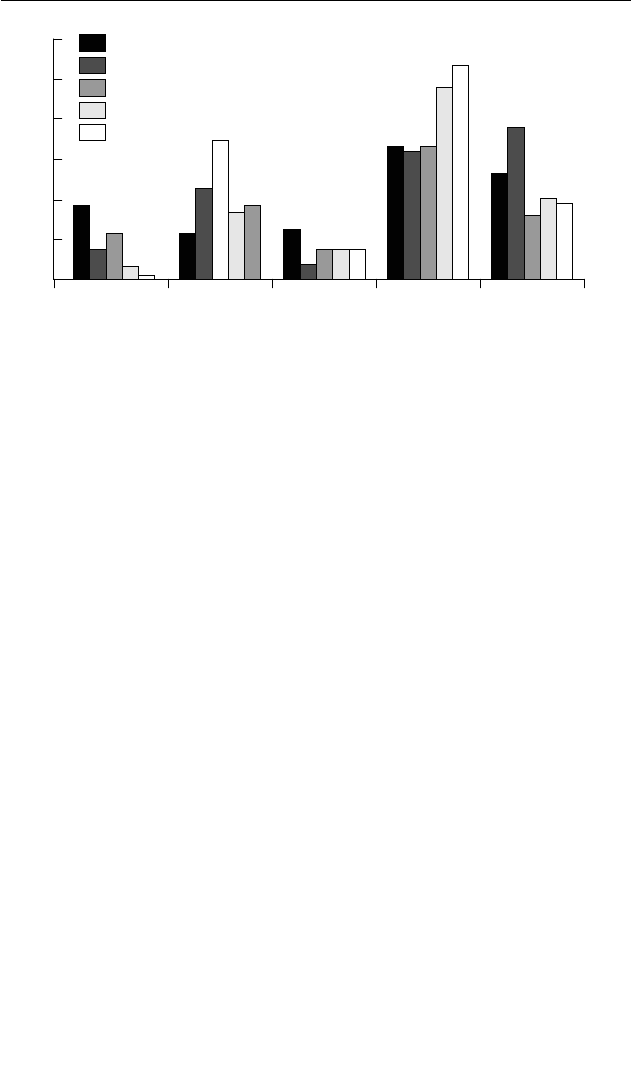

At the start of this period, the

middle classes of Leeds and Glasgow included substantial numbers of commer-

cial and professional people. West Bromwich, Bilston and Wolverhampton were

similar. All included large numbers of tradesmen and shopkeepers.

29

In Oldham, the middling classes of shopkeepers and small masters, often sub-

jected to threats of exclusive dealing in elections, featured in the analysis as

Structure, culture and society in British towns

25

R. S. Neale, Class and Ideology in the Nineteenth Century (London, ), pp. –; R. S. Neale,

Bath, –. A Social History. Or, A Valley of Pleasure,Yet a Sink of Iniquity (London, ); G.

Crossick, An Artisan Elite in Victorian Society (London, ); R. Q. Gray, The Labour Aristocracy in

Victorian Edinburgh (Oxford, ).

26

D. S. Gadian, ‘Class consciousness in Oldham and other North-West industrial towns,

–’, HJ, (), –.

27

C. Behagg, Politics and Production in the Early Nineteenth Century (London, ).

28

V. A. C. Gatrell, ‘Incorporation and the pursuit of Liberal hegemony in Manchester, –’,

in D. Fraser, ed., Municipal Reform and the Industrial City (Leicester, ); Simon Gunn, ‘The

Manchester middle class, –’ (PhD thesis, University of Manchester, ).

29

R. J. Morris, Class, Sect and Party (Manchester, ); Stana Nenadic, ‘The structure, values and

influence of the Scottish urban middle class: Glasgow, –’ (PhD thesis, University of

Glasgow, ); S. Nenadic, ‘The Victorian middle classes’, in W. H. Fraser and I. Maver, eds.,

Glasgow, vol. : – (Manchester, ), pp. –; R. H. Trainor, ‘Authority and social

structure in an industrial area: a study of three Black Country towns, –’ (DPhil thesis,

University of Oxford, ); R. H. Trainor, Black Country Elites (Oxford, ). These measures

were based upon the analysis of trades directories and parliamentary poll books.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

objects of contests between working-class and middle-class elite organisation. In

fact, these middling groups were the creative leadership of local radicalism in

places as varied as Oldham, Bath and Gateshead.

30

There was no simple relation-

ship of economic structure and outcome in terms of conflict and class. Ashton

and Blackburn were both dominated by large firms but Blackburn was a peace-

ful place with a working class apathetic to class action, whilst in Ashton militant

Chartists faced a pro-New Poor Law Board of Guardians. Oldham was a place

of class cooperation radicals whilst nearby Rochdale experienced a more liberal

basis for such cooperation. The nature and response of middle-class leadership

was an important element in explaining differences. In Stockport, effective

repression, especially in the use of blacklists of strikers, was used. Finally, both

radicals and middle-class leaders were influenced by recent local history and

memory. Oldham had a radical tradition drawn from the s whilst the suc-

cessful patronage and manipulation of local culture by Blackburn mill owners

through schools, libraries, reading rooms and Mechanics Institutions was based

upon a coherent response to late eighteenth-century experience of rioting and

mill burning.

31

The relationship between the economic and social structures of

an urban place and political and cultural outcomes was complex.

This account of structures derived from production must be supplemented by

those of reproduction, notably gender, as well as those ‘imagined’ but very real

and powerful identities of ethnicity and sectarianism.

32

R. J. Morris

30

Neale, Class and Ideology, pp. –; T. J. Nossiter, Influence, Opinion and Political Idioms in Reformed

England (Brighton, ).

31

D. S. Gadian, ‘Class formation and class action in North-West industrial towns, –’, in

R. J. Morris, ed., Class, Power and Social Structure in British Nineteenth-Century Towns (Leicester,

), pp. –.

32

Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism

(London, ); Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism (London, ).

60

50

40

30

20

10

Merchants Manufacturers Professional Shopkeepers Tradesmen

0

Glasgow 1832

Leeds 1834

Manchester 1832

West Bromwich 1834

Bilston 1834

Figure . ‘Middle-class’ occupational structure of five British towns –

Sources: as in n. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The early nineteenth century saw a substantial renegotiation of the subordi-

nations of gender around a culture of domesticity. This culture was initially an

expression of the ambitions of the middle classes to assert difference but by mid-

century was a formidable influence on all social classes.

33

The making and impact

of this culture was closely related to the situations, structures and networks of

urbanism. It was fuelled by a variety of cultural products which relied upon the

interactions and markets of the town. Print culture was vital, through news-

papers, periodicals, household and etiquette manuals as well as novels. The

lecture and the sermon from the threatening warmth of the evangelical to the

cold rationality of the unitarian served urban audiences.

34

It was not just as

Vaughan had predicted that the massing of people in the urban place created a

viable market and a critical mass for the exchange of ideas but that the modern

capitalist city was an environment in which the individual became both specta-

tor and actor. The meetings of the voluntary societies, charities, missionary soci-

eties, literary associations first excluded women and then reincorporated them

in subordinate, often passive roles. By the late nineteenth century a deep sense

of physical and moral insecurity derived from the anonymity of the city

expressed itself in a highly gendered form. The brutal Jack the Ripper murders

of several women in the ‘East End’ of London in were horrific enough but

their impact lay in the manner in which they were magnified by all aspects of

urban media from a newspaper press feeding on mass literacy to the ballad sheet

and popular theatre.

35

The most important location for the urban learning of

domesticity and gender were the shopping streets, especially that high point of

development the department store. It was not just a matter of following fashion

or exchanging gossip in the tea shops and restaurants. Shops and department

stores were places were women and men learnt the new domestic technologies,

Kendrick’s coffee grinder, Ransome’s lawn mower, or the new enclosed stoves.

At one level shopping was an aspect of the market economy, but by the end of

the century it was an intensely gendered ceremony which dominated key parts

of the central business district. In Edinburgh, the elaborate architectural deco-

ration of Messrs Jenner’s new department store on Princes’ Street included a

number of female statues ‘giving symbolic expression to the fact that women

have made the business concern a success’.

36

The most important spatial expression of the culture of domesticity was the

middle-class residential suburb. A number of prosperous urban dwellers had

always lived in a scattering of villas around the edges of the great towns. These

had grown in number in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In

Structure, culture and society in British towns

33

L. Davidoff and C. Hall, Family Fortunes (London, ).

34

J. Seed, ‘Theologies of power: unitarianism and the social relations of religious discourse,

–’, in Morris, ed., Class, Power and Social Structure, pp. –

35

J. R. Walkowitz, City of Dreadful Delight (London and Chicago, ).

36

John Reid, The New Illustrated Guide to Edinburgh (Edinburgh, c. ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008