Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ther, amounting to a conceptual revolution that

shook the Soviet system to its foundations.

It was in 1987 that Gorbachev first used the

term “pluralism” in a positive sense, albeit in a

qualified form as “socialist pluralism” or a “plu-

ralism of opinion.” Hitherto, “pluralism” had al-

ways been a pejorative term in the Soviet lexicon,

condemned as an alien and bourgeois notion. Once

the taboo on praising pluralism had been broken,

articles on the need to develop pluralism within the

Soviet Union began to appear, often without the

“socialist” qualifier. By 1990 Gorbachev himself

was advocating “political pluralism.” Another con-

cept on which an anathema had been pronounced

for many years was “market,” but again—for ex-

ample, in his 1987 book—Gorbachev embraced the

idea of a “socialist market.” Before long other con-

tributors to the growing debates in the Soviet

Union were advocating a market economy, some

of them explicitly differentiating this from social-

ism as they understood it.

The New Political Thinking could, in its earli-

est manifestations, be seen as a new Soviet ideol-

ogy, a codified, albeit genuinely innovative, body

of correct thinking. It gave way, however, to a

growing freedom of speech and of debate both

within the Communist Party and in the broader

society—a new political reality that partly resulted

from the boldness of the intellectual breakthrough.

Among the new concepts that were given Gor-

bachev’s official imprimatur between 1985 and

1988 were the principle of a state based on the rule

of law, the idea of checks and balances, glasnost

(openness or transparency), perestroika (literally

reconstruction, but a term that became a synonym

for the radical reform of the Soviet system), de-

mocratization (which initially meant freer discus-

sion within the Communist Party but by 1988—at

the Nineteenth Party Conference—had come to em-

brace the principle of contested elections for a new

legislature), and civil society.

The New Political Thinking represented no less

of a break with the Soviet past in its foreign pol-

icy dimension. A class approach to international re-

lations was explicitly discarded in favor of the idea

of all-human interests and universal values. The

idea of global interdependence superseded the zero-

sum-game philosophy of kto kogo (who will crush

whom). Whereas in the past the “struggle for

peace” had often been a thin disguise for the pur-

suit of Soviet great-power interests, the new think-

ing endorsed by Gorbachev stressed that in the

nuclear age peace was the only rational option if

humankind was to survive. This provided justifi-

cation for a new and genuinely cooperative ap-

proach to international relations.

See also: DEMOCRATIZATION; GLASNOST; GORBACHEV,

MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH; PERESTROIKA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brown, Archie (ed.). (2004). The Demise of Marxism–

Leninism in Russia. London: Palgrave.

Chernyaev, Anatoly. (2000). My Six Years with Gorbachev.

Philadelphia: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Gorbachev, Mikhail. (1987). Perestroika: New Thinking for

our Country and the World. London: Collins.

Nove, Alec. (1989). Glasnost in Action. London: Unwin

Hyman.

Palazchenko, Pavel. (1997). My Years with Gorbachev and

Shevardnadze: The Memoir of a Soviet Interpreter.

Philadelphia: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Yakovlev, Alexander. (1993). The Fate of Marxism in Rus-

sia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

A

RCHIE

B

ROWN

NEWSPAPERS

The first news sheet issued with some regularity

in Russia was Sankt Peterburgskie vedemosti (St.

Petersburg Herald), a biweekly published by the

Imperial Academy of Sciences, beginning in 1727.

Until the Great Reforms of 1861–1874, nearly all

newspapers in Russia were official bulletins issued

by various government institutions. To the extent

that there was a print-based public sphere in pre-

Reform Russia, it was dominated by the “thick

journals” that published literary criticism and

philosophical speculation.

The relaxing of censorship and limits on pri-

vate publications during the Great Reforms, ad-

vances in printing technology, and the spread of

literacy in Russian cities led to the development of

a mass-market, commercial press by the 1880s.

Daily papers targeting various markets covered

stock-market news and foreign affairs, as well as

the more sensational topics of crime, sex scandals,

and natural disasters. As Louise McReynolds has

demonstrated, Russian commercial mass newspa-

pers resembled their counterparts in North Amer-

ica and Western Europe in appealing to and

fostering nationalist sentiment.

NEWSPAPERS

1043

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

By World War I “copeck” (penny) newspapers

in Moscow and St. Petersburg achieved circulations

comparable to those of mass circulation organs in

the United States and Western Europe. The most

popular newspaper in the Russian Empire in 1914

was Russkoe slovo (Russian Word), with a circula-

tion of 619,500.

After the Bolsheviks seized power in October

1917, they created an entirely new kind of mass

press. By the summer of 1918 the Soviet govern-

ment had shut down all non-Bolshevik newspapers

on their territory. Bolshevik newspapers during the

years of revolution and civil war (1917–1921)

aimed to mobilize the populace in general and Party

members in particular for war. Resources were

scarce, and typical civil war newspaper editions

were only two pages long. The state funded the

press throughout the Soviet era.

The Bolsheviks shared with most Russian in-

tellectuals of the revolutionary era a profound con-

tempt for the sensationalistic urban copeck

newspapers that aimed to entertain a mass audi-

ence. They created a mass press that was supposed

to educate, guide, and mobilize readers, not enter-

tain them. Other important functions of Soviet

newspapers were the gathering of intelligence on

popular moods and the monitoring of corruption

in the Party or state apparatus. To fulfill these

tasks, the newspapers solicited and received liter-

ally millions of readers’ letters, some of which were

published. The editorial staff also forwarded letters

denouncing crime and corruption to the appropri-

ate police or prosecutorial organs. They used let-

ters to compose reports on popular attitudes that

were sent to all levels of party officialdom.

The role of direct censorship in Soviet newspa-

per production has been overemphasized. Agenda-

setting by party and state organs was more

important. The role of official censors in control-

ling press content was negligible. Soviet journalists

were generally self-censoring, and they followed

agendas set by the Communist Party’s Central

Committee and other official institutions.

Illegal newspapers were central to Bolshevik

Party organization in the prerevolutionary years.

This heritage of underground political culture con-

tributed to a Soviet fetishization of newspapers as

the mass medium par excellance. As a result of this

fetishization, Communist propaganda officials and

journalists were slow to understand and effectively

use the media of radio and television. By the 1970s,

Soviet means and methods of mass persuasion and

mobilization were far inferior to those developed

by advertising agencies and governments in the

wealthy liberal democracies.

See also: CENSORSHIP; IZVESTIYA; JOURNALISM; PRAVDA;

THICK JOURNALS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brooks, Jeffrey. (2000). Thank You, Comrade Stalin!

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hopkins, Mark. (1970). Mass Media in the Soviet Union.

New York: Pegasus Books.

Kenez, Peter. (1985). The Birth of the Propaganda State:

Soviet Methods of Mass Mobilization, 1917–1929.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

McReynolds, Louise. (1991). The News Under Russia’s Old

Regime. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

M

ATTHEW

E. L

ENOE

NEW STATUTE OF COMMERCE

The New Commerce Statute (a translation of the

Russian Novotorgovy ustav of April 22, 1667; ustav

might also be translated as “regulations”) was the

Russian expression of Western mercantilism and

was sponsored by boyarin Afanasy Lavrentievich

Ordin-Nashchokin (1605–1680), a former gover-

nor of Pskov, the westernmost of Russia’s major

cities, who in 1667 was head of the Chancellery of

Foreign Affairs. The 1667 document was an ex-

pansion of the Commerce Statute (or Regulations)

of 1653, which introduced a unified tariff schedule

while repealing petty transit duties and increasing

protectionist duties against foreigners. The 1667

regulations remained in force until replaced by the

Customs Statute of 1755.

The 1667 document regulated both internal

trade and trade relations with foreigners. In a 1649

petition to the government, the Russian merchants

lamented that they could not compete with the for-

eign merchants, who were forbidden to engage in

internal Russian trade (where they had been giving

favorable credit terms to local, smaller Russian

merchants) and were restricted to the port cities at

times when fairs were being held. The foreigners

were accused of selling shoddy goods, which was

forbidden. Foreigners were forbidden to sell any

goods retail in the provinces or in Moscow, or any

Russian goods among themselves upon pain of con-

fiscation of the merchandise. Internal customs du-

NEW STATUTE OF COMMERCE

1044

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ties of 5 percent were to be collected from Russians

on sales of weighed goods (ad valorem sales) and

4 percent from unweighed goods. A duty of 10 per-

cent was to be collected on salt and 15 percent on

liquor. Excepting liquor, foreigners had to pay a 6

percent duty on their foreign goods sold to autho-

rized Russian wholesalers. A foreigner had to pay

a 10 percent export duty, except when he paid for

the goods with gold and silver currency. The ex-

port of gold and silver from Muscovy was forbid-

den. Local officials (acknowledged by Moscow as

likely to be corrupt) were ordered repeatedly in the

statute not to interfere with commerce. Much pa-

perwork was required to ensure compliance with

the 1667 regulations.

See also: FOREIGN TRADE; MERCHANTS; ORDIN-NASH-

CHOKIN, AFANASY LAVRENTIEVICH.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hellie, Richard, ed. and tr. (1967). Readings for Introduc-

tion to Russian Civilization. Chicago: Syllabus

Division, The College, University of Chicago.

R

ICHARD

H

ELLIE

NICARAGUA, RELATIONS WITH

The Soviet Union had no diplomatic or economic

relations with Nicaragua before the Somozas’ fall

in 1979. Contacts were through Communist Party

organizations such as the Nicaraguan Socialist

Party (PSN), founded in 1937 and illegal until 1979.

While not opposing revolutionary violence in prin-

ciple, the Communists believed that conditions in

Nicaragua were not ripe for armed revolt. A mem-

ber of the Party who had visited the USSR in 1957,

Carlos Fonseca Amador, broke with the PSN on this

issue. He called for insurrection and founded the

Sandinista Front of National Liberation (FSLN) in

1961.

The Sandinistas led the revolutionary upheaval

that overthrew the Somozas in 1979. They took

full control of Nicaragua and ignored the commu-

nists (PSN). Unlike other Soviet satellites, the San-

dinistas left about half of the economy in private

hands, and agriculture was not collectivized. The

FSLN leader, Daniel Ortega, lacked the authority in

the Council of State that Leonid Brezhnev and

Mikhail Gorbachev had in the Soviet Politburo.

In spite of the fact that the Sandinistas’ success

meant defeat for the local Communists, Moscow

quickly established good relations with the San-

dinista government. Soviet economic and military

aid approached billions of rubles, far less than to

Cuba. While offering political, economic, and mil-

itary support, Moscow sought to limit Nicaragua

as an economic and strategic burden. Cuba actively

supported the Sandinistas in Nicaragua and abroad.

Meanwhile, the Reagan administration was

backing an armed paramilitary force, the contras,

which sought to overthrow the Sandinistas. The

United States also aided a right-wing regime in El

Salvador besieged by revolutionary forces suppos-

edly encouraged by the Sandinistas. Both U.S. ef-

forts were inconclusive.

Early in 1990 President George Bush and Gen-

eral Secretary Gorbachev began cooperating in the

region, as they were in Eastern Europe, to end these

conflicts. Central American countries, the United

Nations, and the two great powers negotiated a re-

gional settlement. The United States stopped sup-

porting the contras, the Sandinistas agreed to free

elections, and the USSR mollified Cuba. Later Or-

tega was defeated in the elections for the Nicara-

guan presidency, and Moscow was no longer an

actor on the Central American scene.

See also: CUBA, RELATIONS WITH; UNITED STATES, RELA-

TIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blachman, Morris J.; Leogrande, William; and Sharpe,

Kenneth. (1986). Confronting Revolution: Security

through Diplomacy in Central America. New York:

Pantheon.

Blasier, Cole. (1987). The Giant’s Rival: The USSR and Latin

America. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh

Press.

C

OLE

B

LASIER

NICHOLAS I

(1796–1855), tsar and emperor of Russia from

1825 to 1855.

Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov came to power

amid the Decembrist Revolt of 1825 and died dur-

ing the Crimean War. Between these two events,

Nicholas became known throughout his empire

and the world as the quintessential autocrat, and

his Nicholaevan system as the most oppressive in

Europe.

NICHOLAS I

1045

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

When Nicholas I was on his deathbed, he spoke

his last words to his son, soon to become Alexan-

der II: “I wanted to take everything difficult, every-

thing serious, upon my shoulders and to leave you

a peaceful, well-ordered, and happy realm. Provi-

dence decreed otherwise. Now I go to pray for Rus-

sia and for you all.” Earlier in the day, Nicholas

ordered all the Guards regiments to be brought to

the Winter Palace to swear allegiance to the new

tsar. These words and actions reveal a great deal

about Nicholas’s personality and his reign. Nicholas

was a tsar obsessed with order and with the mili-

tary, and his thirty years on the throne earned him

a reputation as the Gendarme of Europe. His fear

of rebellion and disorder, particularly after the

events of his ascension to the throne, would affect

him for the remainder of his reign.

EDUCATION, DECEMBER 1825,

AND RULE

Nicholas I was not intended to be tsar, nor was he

educated to be one. Born in 1796, Nicholas was the

third of Paul I’s four sons. His two elder brothers,

Alexander and Constantine, received upbringings

worthy of future rulers. In 1800, by contrast, Paul

appointed General Matthew I. Lamsdorf to take

charge of the education of Nicholas and his younger

brother, Mikhail. Lamsdorf believed that education

consisted of discipline and military training, and he

imposed a strict regimen on his two charges that

included regular beatings. Nicholas thus learned to

respect the military image his father cultivated and

the necessity of order and discipline.

Although Nicholas received schooling in more

traditional subjects, he responded only to military

science and to military training. In 1814, during

the war against Napoleon, he gave up wearing

civilian dress and only appeared in his military uni-

form, a habit he kept. Nicholas also longed during

the War of 1812 to see action in the defense of Rus-

sia. His brother, Alexander I, wanted him to remain

in Russia until the hostilities ended. Nicholas only

joined the Russian army for the victory celebrations

held in 1814 and 1815. The young Nicholas de-

buted as a commander and was impressed with the

spectacles and their demonstration of Russian po-

litical power. For Nicholas, as Richard Wortman

has noted, these parades provided a lifelong model

for demonstrating political power.

After the war, Nicholas settled into the life of

a Russian grand duke. He toured his country and

Europe between 1816 and 1817. In 1817 Nicholas

married Princess Charlotte of Prussia, who was

baptized as Grand Duchess Alexandra Fyodorovna.

The following year, in April 1818, Nicholas became

the first of his brothers to father a son, Alexander,

the future Alexander II. For the next seven years,

the family lived a quiet life in St. Petersburg’s

Anichkov Palace; Nicholas later claimed this period

was the happiest of his life. The idyll was only bro-

ken once, in 1819, when Alexander I surprised his

brother with the news that he, and not Constan-

tine, might be the successor to the Russian throne.

Alexander and Constantine did not have sons, and

the latter had decided to give up his rights to the

throne. This agreement was not made public, and

its ambiguities would later come back to haunt

Nicholas.

Alexander I died in the south of Russia in No-

vember 1825. The news of the tsar’s death took

several days to reach the capital, where it caused

confusion. Equally stunning was the revelation

that Nicholas would succeed Alexander. Because of

the secret agreement, disorder reigned briefly in St.

Petersburg, and Nicholas even swore allegiance to

his older brother. Only after Constantine again re-

nounced his throne did Nicholas announce that he

would become the new emperor on December 14.

This decision and the confusion surrounding it

gave a group of conspirators the chance they had

sought for several years. A number of Russian of-

ficers who desired political change that would

transform Russian from an autocracy rebelled at

the idea of Nicholas becoming tsar. His love for the

military and barracks mentality did not promise

reform, and so three thousand officers refused to

swear allegiance to Nicholas on December 14. In-

stead, they marched to the Senate Square where

they called for a constitution and for Constantine

to become tsar. Nicholas acted swiftly and ruth-

lessly. He ordered an attack of the Horse Guards on

the rebels and then cannon fire, killing around one

hundred. The rest of the rebels were rounded up

and arrested, while other conspirators throughout

Russia were incarcerated in the next few months.

Although the Decembrist revolt proved ineffec-

tive, its specter continued to haunt Nicholas. His

first day in power had brought confusion, disor-

der, and rebellion. During the next year, Nicholas

pursued policies and exhibited characteristics that

would define his rule. He personally oversaw the

interrogations and punishments of the Decem-

brists, and informed his advisors that they should

be dealt with mercilessly because they had violated

the law. Five of the leaders were executed; dozens

NICHOLAS I

1046

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

went into permanent Siberian exile. At the same

time he pursued justice against the Decembrists,

Nicholas established a new concept of imperial rule

in Russia, one that relied upon the parade ground

and the court as a means of demonstrating power

and order. Within the first few months of his rule,

he initiated ceremonies and reviews of military and

dynastic might that became hallmarks of his reign.

Above all, the Decembrist revolt convinced Nicholas

that Russia needed order and firmness and that only

the autocrat could provide them.

The Nicholaevan system of government built

upon these ideas and upon the tsar’s mistrust for

the Russian gentry in the wake of the Decembrist

Revolt. Nicholas placed a circle of ministers in im-

portant positions and relied on them almost exclu-

sively to govern. He also used His Majesty’s Own

Chancery, the private bureau for the tsar’s personal

needs, to rule. Nicholas divided the Chancery into

sections to exert personal control over the func-

tions of governing—the First Section continued to

be responsible for the personal needs of the tsar,

the Second Section was established to enact legis-

lation and codify Russian laws, and the Fourth was

responsible for welfare and charity. The Third Sec-

tion, established in 1826, gained the most notori-

ety. It had the task of enforcing laws and policing

the country, but in practice the Third Section did

much more. Headed by Count Alexander Beck-

endorff, the Third Section set up spies, investiga-

tors, and gendarmes throughout the country. In

effect, Nicholas established a police state in Russia,

even if it did not function efficiently.

It was through the Second Section that Nicholas

achieved the most notable reform of his reign.

Established in 1826 to rectify the disorder and con-

fusion within Russia’s legal system that had man-

ifested itself in the Decembrist revolt, the Second

Section compiled a new Code of Law, which was

promulgated in 1833. Nicholas appointed Mikhail

Speransky, Alexander I’s former advisor, to head

the committee. The new code did not so much make

new laws as collect all those that had been passed

since the last codification in 1648 and categorize

them. Published in forty-eight volumes with a di-

gest, Russia had a uniform and ordered set of laws.

Nicholas came to epitomize autocracy in his

own lifetime, largely through the creation of an of-

ficial ideology that one of his advisers formulated

in 1832. Traumatized by the events of 1825 and

the calls for constitutional reform, Nicholas be-

lieved fervently in the necessity of Russian auto-

cratic rule. Because he had triumphed over his

opponents, he searched for a concrete expression of

the superiority of monarchy as the institution best

suited for order and stability. He found a partner

in this quest in Count Sergei Uvarov (1786–1855),

later the minister of education. Uvarov articulated

the concept of Official Nationality, which in turn

became the official ideology of Nicholas’s Russia.

It had three components: Orthodoxy, Autocracy,

and Nationality.

Uvarov’s formula gave voice to trends within

the Nicholaevan system that had developed since

1825. For Nicholas and his minister, an ordered

system could function only with religious princi-

ples as a guide. By invoking Orthodoxy, Uvarov

also stressed the Russian Church as a means to in-

still these principles. The concept of Autocracy was

the clearest of the principles—only it could guar-

antee the political existence of Russia. The third

concept was the most ambiguous. Although usu-

ally translated as “nationality,” the Russian term

used was narodnost, which stressed the spirit of the

Russian people. Broadly speaking, Nicholas wanted

NICHOLAS I

1047

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

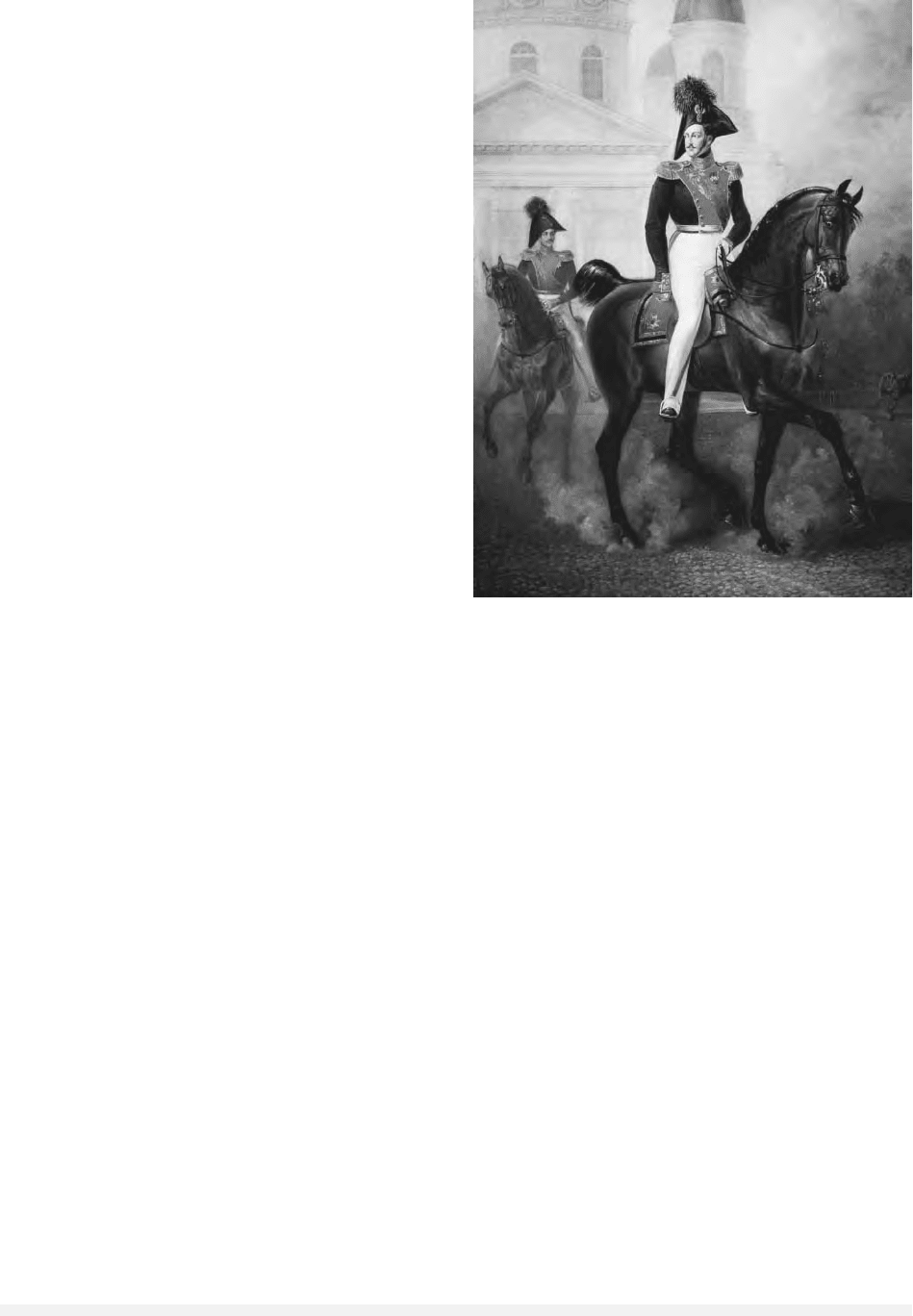

Equestrian portrait of Nicholas I by Alexander Petrovich

Schwabe. © A

RCHIVO

I

CONOGRAFICO

, S.A./CORBIS

to emphasize the national characteristics of his peo-

ple, as well as their spirit, as a principle that made

Russia superior to the West.

Nicholas attempted to rule Russia according to

these principles. He oversaw the construction of

two major Orthodox cathedrals that symbolized

Russia and its religion—St. Isaac’s in St. Petersburg

(begun in 1768 and finished under Nicholas) and

Christ the Savior in Moscow (Nicholas laid the

cornerstone in 1837 but it was not finished until

1883). He dedicated the Alexander column on Palace

Square to his brother in 1834 and a statue to his

father, Paul I, in 1851. Nicholas also held count-

less parades and drills in the capital that included

his sons, another demonstration of the might and

timelessness of the Russian autocracy. Finally,

Nicholas cultivated national themes in performances

and festivals held throughout his empire. Most

prominently, Mikhail Glinka’s A Life for the Tsar

(1836) became the national opera, while General

Alexander Lvov and Vasily Zhukovsky’s “God Save

the Tsar” became Russia’s first national anthem in

1833.

Nicholas also dealt with two other areas of

Russian society. The first involved local govern-

ment and ruling over such a vast country, long a

problem for Russian monarchs. Nicholas oversaw

a reform in the local government in 1837 that

granted more power to the governors. More im-

portantly, Nicholas expanded the Russian bureau-

cracies and training for the civil service. The

Nicholaevan system thus became synonymous

with bureaucrats, as the writings of Nikolai Gogol

brilliantly depict.

The second pressing concern was serfdom.

Nicholas appointed a secret committee in 1835 that

tackled the question of reform, and even abolition,

of serfdom. Led by Paul Kiselev (1788–1872), the

committee recommended abolition, but its conclu-

sions were not implemented. Instead, Nicholas de-

clared serfdom an evil but emancipation even more

problematic. He had Kiselev head a Fifth Section of

the Chancery in 1836 and charged him with im-

proving farming methods and local conditions. Fi-

nally, Nicholas passed a law in 1842 that allowed

serf owners to transform their serfs into “obligated

peasants.” Few did so, and while continued com-

mittees recommended abolition, Nicholas halted

short of freeing Russia’s serfs. By 1848, therefore,

Nicholas had established a system of government

associated with Official Nationality, order, and

might.

WAR, 1848, AND THE

CRIMEAN DEBACLE

Nicholas defined himself and his system as a mili-

taristic one, and the first few years of his rule

also witnessed his consolidation of power through

force. He continued the wars in the Caucasus begun

by Alexander I, and consolidated Russian power in

Transcaucasia by defeating the Persians in 1828. Rus-

sia also fought the Ottoman Empire in 1828–1829

over the rights of Christian subjects in Turkey and

disagreements over territories between the two em-

pires. Although the fighting produced mixed results,

Russia considered itself a victor and gained conces-

sions. One year later, in 1830, a revolt broke out

in Poland, an autonomous part of the Russian Em-

pire. The revolt spread from Warsaw to the west-

ern provinces of Russia, and Nicholas sent in troops

to crush it in 1831. With the rebellion over, Nicholas

announced the Organic Statute of 1832, which in-

creased Russian control over Polish affairs. The Pol-

ish revolt brought back memories of 1825 for

Nicholas, who responded by pushing further Rus-

sification programs throughout his empire. Order

reigned, but nationalist reactions in Poland, Ukraine,

and elsewhere would ensure problems for future

Russian rulers.

Nicholas also presided over increasingly op-

pressive measures directed at any forms of per-

ceived opposition to his rule. Russian culture began

to flourish in the decade between 1838 and 1848,

as writers from Mikhail Lermontov to Nikolai

Gogol and critics such as Vissarion Belinsky and

Alexander Herzen burst onto the Russian cultural

scene. Eventually, as their writings increasingly

criticized the Nicholaevan system, the tsar cracked

down, and his Third Section arrested numerous in-

tellectuals. Nicholas’s reputation as the quintes-

sential autocrat developed from these policies,

which reached an apex in 1848. When revolutions

broke out across Europe, Nicholas was convinced

that they were a threat to the existence of his sys-

tem. He sent Russian troops to crush rebellions in

Moldavia and Wallachia in 1848 and to support

Austrian rights in Lombardy and Hungary in 1849.

At home, Nicholas oversaw further censorship and

repressions of universities. By 1850, he had earned

his reputation as the Gendarme of Europe.

In 1853, Nicholas’s belief in the might of his

army set off a disaster for his country. He pro-

voked a war with the Ottoman Empire over con-

tinued disputes in the Holy Land that brought an

unexpected response. Alarmed by Russia’s aggres-

sive policies, England and France joined the Ot-

NICHOLAS I

1048

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

toman Empire in declaring war. The resulting

Crimean War led to a humiliating defeat and the

exposure of Russian military weakness. The war

also exposed the myths and ideas that guided

Nicholaevan Russia. Nicholas did not live to see the

final humiliation. He caught a cold in 1855 that

grew serious, and he died on February 18. His

dream of creating an ordered state for his son to

inherit died with him.

Alexander Nikitenko, a former serf who worked

as a censor in Nicholas’s Russia, concluded: “The

main shortcoming of the reign of Nicholas con-

sisted in the fact that it was all a mistake.” Con-

temporaries and historians have judged Nicholas

just as harshly. From Alexander Herzen to the Mar-

quis de Custine, the image of the tsar as tyrant cir-

culated widely in Europe during Nicholas’s rule.

Russian and Western historians ever since have

largely seen Nicholas as the most reactionary ruler

of his era, and one Russian historian in the 1990s

argued “it would be difficult to find a more odious

figure in Russian history than Nicholas I.” W. Bruce

Lincoln, Nicholas’s most recent American biogra-

pher (1978), argued that Nicholas in many ways

helped to pave the way for more significant reforms

by expanding the bureaucracies. Still, his conclu-

sion serves as an ideal epitaph for Nicholas: He was

the last absolute monarch to hold undivided power

in Russia. His death brought the end of an era.

See also: ALEXANDER I; ALEXANDRA FEDOROVNA; AU-

TOCRACY; CRIMEAN WAR; DECEMBRIST MOVEMENT

AND REBELLION; NATIONAL POLICIES, TSARIST;

UVAROV, SERGEI SEMENOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Curtiss, J. H. (1965). The Russian Army under Nicholas I,

1825–1855. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Custine, Astolphe, Marquis de. (2002). Letters From Rus-

sia. New York: New York Review of Books.

Gogol, Nikolai. (1995). Plays and Petersburg Tales. Ox-

ford: Oxford University Press.

Herzen, Alexander. (1982). My Past and Thoughts. Berke-

ley: University of California Press.

Kasputina, Tatiana. (1996). “Emperor Nicholas I, 1825-

1855.” In The Emperors and Empresses of Russia: Re-

discovering the Romanovs, ed. Donald Raleigh.

Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Lincoln, W. Bruce. (1978). Nicholas I: Emperor and Auto-

crat of All the Russias. Bloomington: Indiana Uni-

versity Press.

Lincoln, W. Bruce. (1982). In the Vanguard of Reform: Rus-

sia’s Enlightened Bureaucrats, 1825–1861. DeKalb:

Northern Illinois University Press.

Riasanovsky, Nicholas. (1959). Nicholas I and Official Na-

tionality in Russia, 1825–1855. Berkeley: University

of California Press.

Whittaker, Cynthia. The Origins of Modern Russian Edu-

cation: An Intellectual Biography of Count Sergei

Uvarov, 1786–1855. DeKalb: Northern Illinois Uni-

versity Press.

Wortman, Richard. (1995). Scenarios of Power: Myth and

Ceremony in Russian Monarchy, Vol. 1: From Peter the

Great to the Death of Nicholas I. Princeton, NJ: Prince-

ton University Press.

S

TEPHEN

M. N

ORRIS

NICHOLAS II

(1868–1918), last emperor of Russia.

The future Nicholas II was born at Tsarskoe Selo

in May 1868, the first child of the heir to the Russ-

ian throne, Alexander Alexandrovich, and his Dan-

ish-born wife, Maria Fedorovna. Nicholas was

brought up in a warm and loving family environ-

ment and was educated by a succession of private

tutors. He particularly enjoyed the study of history

and proved adept at mastering foreign languages,

but found it much more difficult to grasp the com-

plexities of economics and politics. Greatly influ-

enced by his father, who became emperor in 1881

as Alexander III, and by Konstantin Pobedonostsev,

one of his teachers and a senior government offi-

cial, Nicholas was deeply conservative, a strong be-

liever in autocracy, and very religious. At the age

of nineteen, he entered the army, and the military

was to remain a passion throughout his life. After

three years service in the army, Nicholas was sent

on a ten-month tour of Europe and Asia to widen

his experience of the world.

In 1894 Alexander III died and Nicholas became

emperor. Despite his broad education, Nicholas felt

profoundly unprepared for the responsibility that

was thrust upon him and contemporaries re-

marked that he looked lost and bewildered. Within

a month of his father’s death, Nicholas married; he

had become engaged to Princess Alix of Hesse in the

spring of 1894 and his accession to the throne made

marriage urgent. The new empress, known in Rus-

sia as Alexandra, played a crucial role in Nicholas’s

life. A serious and devoutly religious woman who

believed fervently in the autocratic power of the

NICHOLAS II

1049

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Russian monarchy, she stiffened her husband’s re-

solve at moments of indecision.

The couple had five children, Olga (b. 1895),

Tatiana (b. 1897), Maria (b. 1899), Anastasia (b.

1901), and Alexei (b. 1904). The birth of a son and

heir in 1904 was the occasion for great rejoicing,

but this was soon marred as it became clear that

Alexei suffered from hemophilia. Their son’s illness

drew Nicholas and Alexandra closer together. The

empress had an instinctive aversion to high soci-

ety, and the imperial family spent most of their

time at Tsarskoe Selo, only venturing into St. Pe-

tersburg on formal occasions.

While Nicholas’s reign began with marriage

and personal happiness, his coronation in 1896 was

marked by disaster. Public celebrations were held

at Khodynka on the outskirts of Moscow, but the

huge crowds that had gathered there got out of

hand and several thousand people were crushed to

death. That night the newly crowned emperor and

empress appeared at a ball, apparently oblivious to

the catastrophe. The image of Nicholas II enjoying

himself while many of his subjects lay dead gave

his reign a sour start.

THE RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR

Nicholas followed his father’s policies for much of

his first decade as monarch, relying on the men

who had advised Alexander III, especially Sergei

Witte, the minister of finance and the architect of

Russia’s economic growth during the 1890s. Russ-

ian industry grew rapidly during the decade, aided

by investment from abroad and particularly from

France, assisted by a political alliance between the

two countries signed during the last months of

Alexander III’s reign. Russia was also expanding in

NICHOLAS II

1050

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

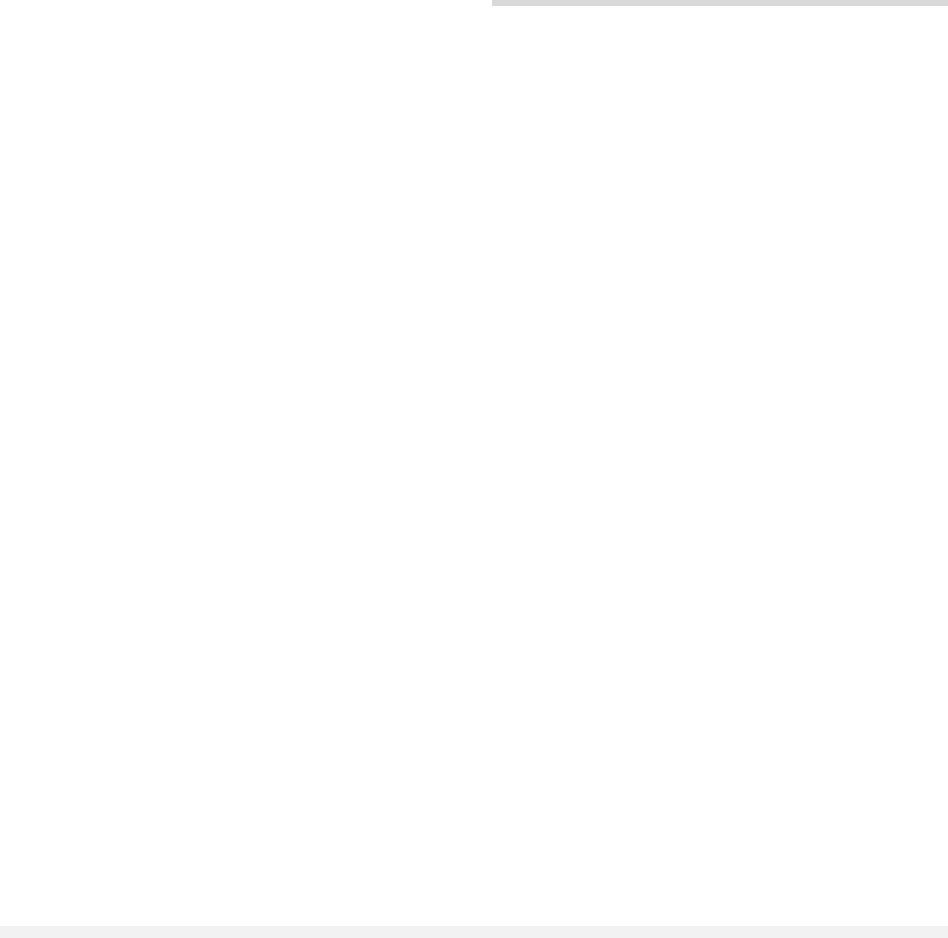

Coronation of Nicholas II, Russian engraving. T

HE

A

RT

A

RCHIVE

/B

IBLIOTHÈQUE DES

A

RTS

D

ÉCORATIFS

P

ARIS

/D

AGLI

O

RTI

the Far East. The construction of the Trans-Siberian

Railroad, linking European Russia with the empire’s

Pacific coast, had begun in 1891, and this resur-

gence of Russian interest in the region worried

Japan. The twin developments of industrialization

and Far Eastern expansion both came to a head

early in the twentieth century. In 1904, Japan

launched an attack on Russia. Nicholas II believed

this was no more than “a bite from a flea,” but his

confidence in Russia’s armed forces was misplaced.

The Japanese inflicted a crushing and humiliating

defeat on them, forcing the army to surrender Port

Arthur in December 1904 and destroying the Russ-

ian fleet in the Battle of Tsushima in May 1905.

THE REVOLUTION OF 1905

The emperor was stoical about Russia’s military

failure, but by the time peace negotiations began

in the summer of 1905, the war with Japan was

no longer the central problem. On January 9, 1905,

a huge demonstration took place in St. Petersburg,

calling for better working conditions, political

changes, and a popular representative assembly.

Although the demonstrators were peaceful, troops

opened fire on them, killing more than a thousand

people on what came to be known as “Bloody Sun-

day.” This opened the floodgates of discontent.

Workers throughout the Russian Empire went out

on strike to show sympathy with their 1905 slain

compatriots. As spring arrived, peasants across

Russia voiced their discontent. There were more

than three thousand instances of peasant unrest

where troops were required to subdue villagers.

Nicholas II’s reaction was confused. Believing

that he had a God-given right to rule Russia and

must pass his patrimony on unchanged to his heir,

he tried to put down the revolts by force and re-

sisted any attempt to erode his authority. But this

tactic did not stem the surge of urban and rural

discontent, and the fragility of the regime’s posi-

tion was brought home to him by the assassina-

tion of his uncle, the governor-general of Moscow,

Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, in February.

Against his natural instincts, the emperor agreed

to a series of concessions, culminating in October

with the establishment of an elected legislature, the

Duma. Nicholas resented this encroachment on his

autocratic prerogatives and resentfully blamed it on

Witte, the chief author of the October Manifesto.

“There was no other way out,” Nicholas wrote to

his mother immediately afterwards “than to cross

oneself and give what everyone was asking for.”

The emperor’s character is shown in sharp focus

by the events of 1905. Nicholas was a determined

man who knew his own mind and had a clear sense

of where his duty lay. But he was stubborn and

very slow to recognize the need for change.

Nicholas found it difficult to accept that his

powers had been limited, and he tried to act as

though he were still an autocrat. He was encour-

aged in this by the government’s ability to put

down the rebellions across Russia. The appointment

in April 1906 of a new minister of the interior, Pe-

ter Stolypin, marked the beginning of a policy of

repression combined with reform. Elevated to prime

minister in the summer of 1906 because of his suc-

cess in quelling discontent, Stolypin recommended

a wide range of reforms. Nicholas II, however, did

not agree on the need for reform. Once an uneasy

calm had been reestablished across the empire, he

concluded that further change was unnecessary.

Nicholas wanted to return to the pre-1905 situa-

tion and to continue to rule as an autocrat. The

1913 celebration of the tercentenary of the Ro-

NICHOLAS II

1051

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

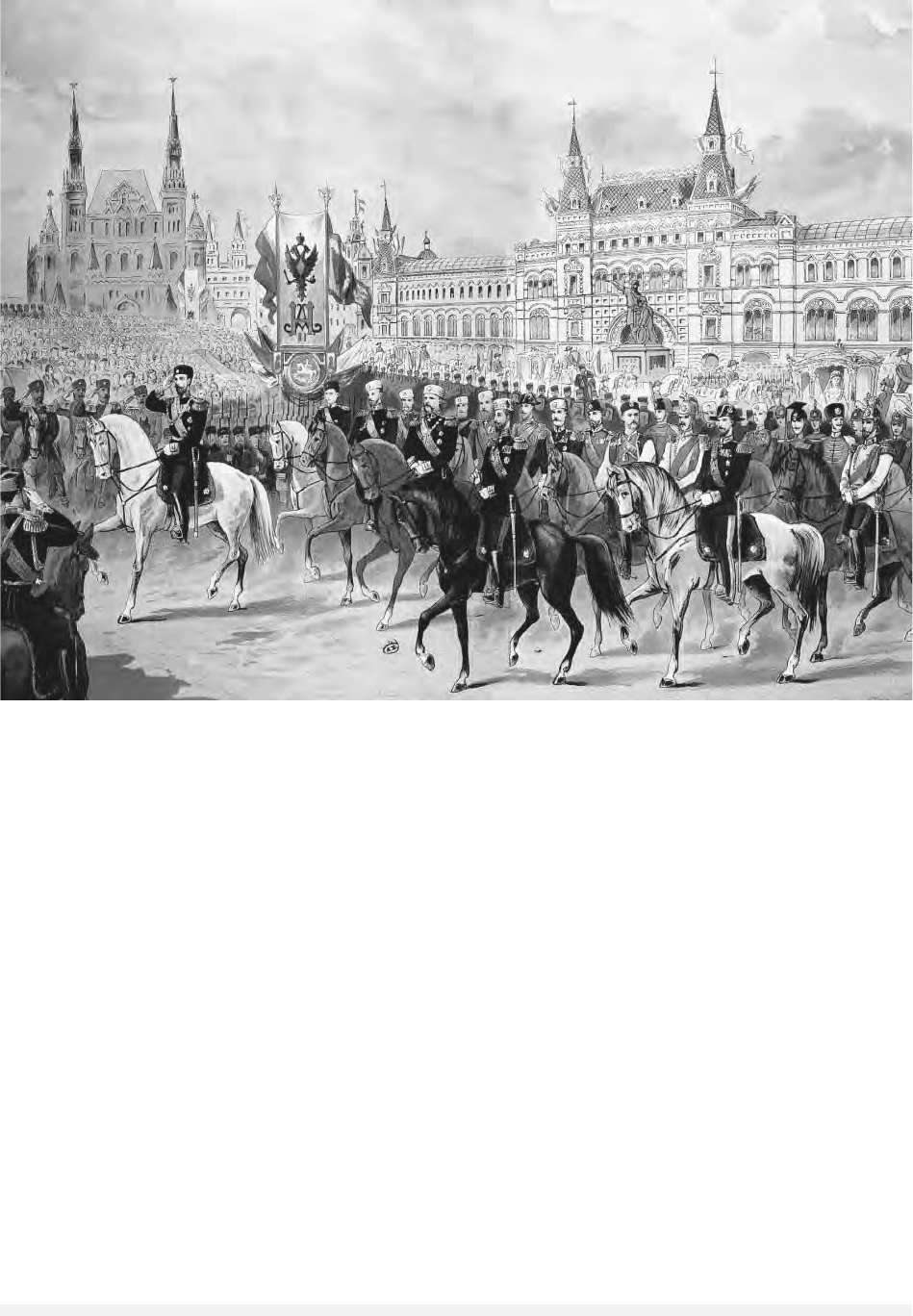

Nicholas II leads Russian soldiers marching off to World War I.

© B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

manov dynasty gave ample illustration of his view

of the situation—he and the empress posed for pho-

tographs dressed in costumes styled to reflect their

ancestors in the seventeenth century. Nicholas

wanted to hark back to an earlier age and reclaim

the power held by his forebears.

WORLD WAR I

The test of World War I exposed Nicholas’s weak-

nesses. The dismal performance of the Russian

armies in the early stages of the war brought his

sense of duty to the fore and he took direct charge

of the army as commander-in-chief, although his

ministers tried to dissuade him, arguing that he

would now be personally blamed for any further

military failures. Nicholas was, however, con-

vinced that he should lead his troops at this crit-

ical moment, and after August 1915 he spent

most of his time at headquarters away from Pet-

rograd (as St. Petersburg had been renamed when

the war began). This had important consequences

for the government of the empire. The empress

was one of the main conduits by which Nicholas

learned what was happening in the capital, and in

his absence she became increasingly reliant on

Rasputin, a “holy man” who had gained the trust

of the imperial family through the comfort he was

able to offer the hemophiliac Alexei. The empress,

already isolated from Petrograd society, grew even

more distant during the war and was highly sus-

ceptible to Rasputin’s influence. She wrote to

Nicholas frequently at headquarters, giving him

the views of “Our friend” (as she termed Rasputin)

on ministerial appointments and other political

matters. The emperor too was a lonely figure as

the war progressed. He had alienated much of Rus-

sia’s moderate political opinion even before 1914,

and the regime’s refusal to countenance any par-

ticipation in government by these parties, even as

the military situation worsened, had caused atti-

tudes to harden on both sides. Wider popular

opinion also turned against the emperor. Alexan-

dra’s German background gave rise to a wide-

spread belief that she wanted a Russian defeat, and

this, allied with increasingly extravagant rumors

about Rasputin, served to discredit the imperial

family.

ABDICATION AND DEATH

When demonstrations and riots broke out in Petro-

grad at the end of February 1917, there was no

segment of society that would support the monar-

chy. Nicholas was at headquarters at Mogilev, four

hundred miles south of the capital, and his attempt

to return to Petrograd by train was thwarted. Mil-

itary commanders and politicians urged him to al-

low parliamentary rule, but even at this critical

moment, Nicholas clung to his belief in his own au-

tocracy. “I am responsible before God and Russia for

everything that has happened and is happening,” he

told his generals. His failure to make immediate con-

cessions cost Nicholas his throne. By the time he was

willing to compromise, the situation in Petrograd

had so deteriorated that abdication was the only ac-

ceptable solution. On March 2 he gave up the throne,

in favor of his son. After medical advice that Alexei

was unfit, he offered the throne to his brother,

Mikhail. When he refused, the Romanov dynasty

came to an end.

In the aftermath of the revolution, negotiations

took place to enable Nicholas and his family to seek

exile in Britain. These came to nothing because the

British government feared a popular reaction if it

NICHOLAS II

1052

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

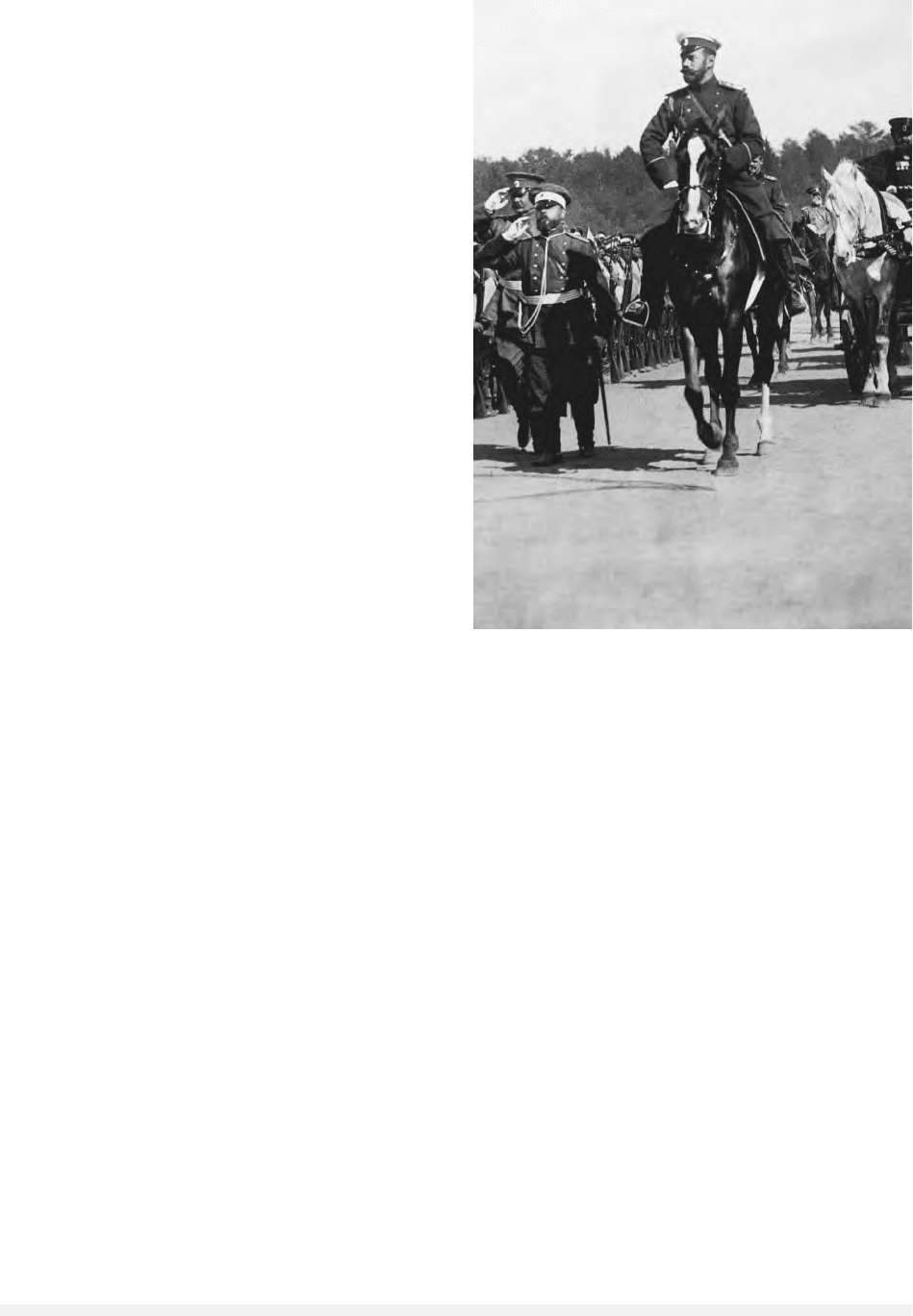

Nicholas II in full military dress. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS