Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PRIMAKOV, YEVGENY MAXIMOVICH

(b. 1929), orientalist, intelligence chief, foreign

minister, and prime minister under Boris Yeltsin.

Born in Kiev, Yevgeny Maximovich Primakov

grew up in Tbilisi; his father disappeared in the

purges. Trained as an Arabist, Primakov worked in

broadcasting in the 1950s and then became a Mid-

dle East correspondent for Pravda (and perhaps a

covert foreign intelligence operative). In the 1970s

he assumed academic posts as deputy director of

the Institute of World Economics and International

Relations (IMEMO), then as director of the Institute

of Oriental Studies, and in 1985 as director of

IMEMO.

In 1986 Primakov became a candidate member

of the Central Committee of the Communist Party

of the Soviet Union, and a foreign policy advisor

to Mikhail Gorbachev. He was chosen in June 1989

to chair the Congress of People’s Deputies, the lower

house of the Supreme Soviet formed pursuant to

Gorbachev’s new constitution. His party status

rose accordingly: full Central Committee member

in April 1989 and candidate member of the Polit-

buro in September. He was a leading contributor

to the “New Thinking” regarding international co-

operation that was identified with Gorbachev.

Primakov condemned the attempted coup by

hard-line communists in August 1991; Gorbachev

then made him First Deputy Chairman of the KGB

and head of foreign intelligence. He was one of the

few Gorbachev appointees to be retained in office

by Russian President Boris Yeltsin after the Soviet

Union was dissolved in December 1991.

Appointed foreign minister in January 1996,

Primakov was a realistic and cool professional. He

was a strong defender of Russian national interests,

as opposed to the pro-Western stance of his prede-

cessor Andrei Kozyrev, and often manifested pro-

Arab sympathies. Espousing a “multipolar” world,

he nonetheless avoided direct confrontation with

the West and bargained for a Russian presence at

NATO as it was expanding eastward. Later he crit-

icized the 1999 NATO bombing campaign against

Yugoslavia but kept open a Russian role in the

Kosovo settlement.

Following the August 1998 economic and po-

litical crisis, Primakov emerged as a compromise

candidate for prime minister. Overwhelmingly con-

firmed by the Duma in September, he was the most

popular politician in Russia. His model for eco-

nomic stabilization was President Franklin Roo-

sevelt’s New Deal in the United States.

As prime minister, Primakov soon aroused the

jealousy of the ailing Yeltsin and alarmed the pres-

ident’s family and cronies by investigating corrup-

tion. Yeltsin emerged from a long period of torpor

and dismissed Primakov in May 1999 in favor

of Interior Minister Sergei Stepashin. In reply, Pri-

makov accepted the leadership of the “Fatherland-

All Russia” bloc to oppose Yeltsin’s forces in the

Duma elections of December 1999, and was a

strong contender for the presidency in the elections

due the following year. But in August Yeltsin re-

placed Prime Minister Stepashin with Vladimir

Putin, who set up his own party, Unity, and cap-

italized on the war in Chechnya to forge ahead of

Primakov’s people. Primakov withdrew as a pres-

idential contender in order to run for speaker of the

new Duma; however, Putin made a deal with the

communists to keep Gennady Seleznyov as speaker

PRIMAKOV, YEVGENY MAXIMOVICH

1223

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

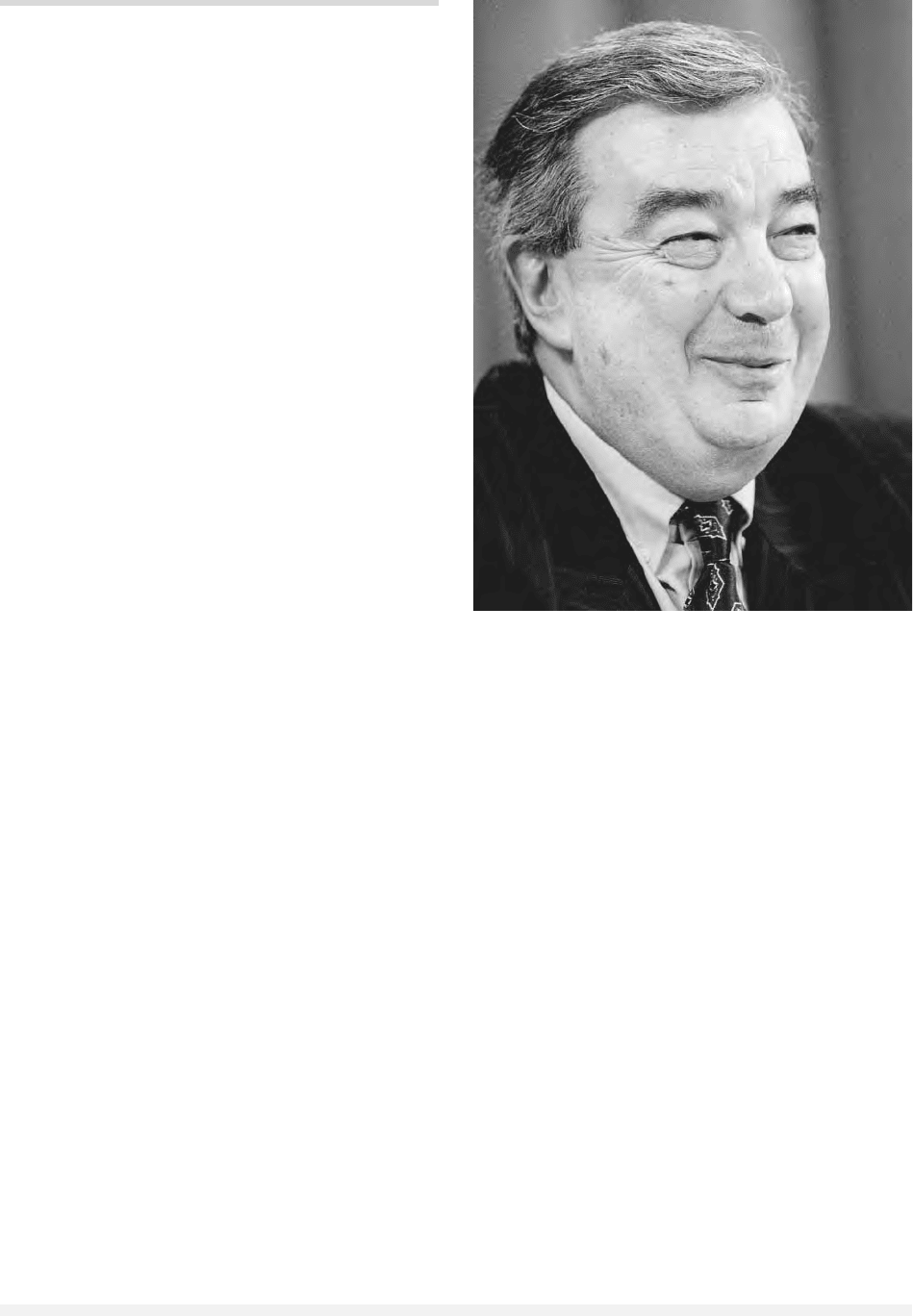

Russian statesman Yevgeny Primakov served Boris Yeltsin as

foreign minister, prime minister, and spy master. P

HOTOGRAPH BY

A

LEXANDER

Z

EMLIANICHENKO

. AP/WIDE WORLD PHOTOS. R

EPRODUCED

BY PERMISSION

.

and marginalize Primakov. Those maneuvers not-

withstanding, in the March 2000 election Primakov

endorsed Putin, who subsequently tapped him for

occasional diplomatic missions. In 2001 Primakov

retired from the presidency of Fatherland-All Rus-

sia as it was preparing to merge with Unity.

See also: FATHERLAND-ALL RUSSIA; GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL

SERGEYEVICH; YELTSIN, BORIS NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Daniels, Robert V. (1999). “Evgenii Primakov: Contender

by Chance.” Problems of Post-Communism 46(5):

27–36.

Shevtsova, Lilia F. (1999). Yeltsin’s Russia: Myths and Re-

ality. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for In-

ternational Peace.

Simes, Dmitri K. (1999). After the Collapse: Russia Seeks

Its Place as a Great Power. New York: Simon & Schus-

ter.

R

OBERT

V. D

ANIELS

PRIMARY CHRONICLE

The compilation of chronicle entries known as the

Povst’ vremennykh lt (PVL) is a fundamental source

for the historical study of the vast eastern Euro-

pean and Eurasian lands that include major parts

of Ukraine and Belarus, as well as extensive parts

of the Russian Federation and Poland. As the sin-

gle most important source for the study of the early

Rus principalities, it contains the bulk of existing

written information about the area inhabited by

the East Slavs from the ninth to the twelfth cen-

tury, and has been the subject of many historical,

literary, and linguistic analyses. The PVL in vari-

ous versions appears at the beginning of most

extant chronicles compiled from the fourteenth

through seventeenth centuries

The PVL may have been compiled initially by

Silvestr, the hegumen of St. Michael’s Monastery

in Vydobichi, a village near Kiev, in 1116. The at-

tribution to Silvestr is based on a colophon in copies

of the so-called Laurentian branch where he de-

clares, “I wrote down this chronicle,” and asks to

be remembered in his readers’ prayers (286,1–286,7).

It is possible that Silvestr merely copied or edited

an already existing complete work by the Kiev

Caves Monastery monk mentioned in the heading

(i.e., “The Tale of Bygone Years of a monk of the

Feodosy Pechersky Monastery [regarding] from

where the Rus lands comes and who first in it be-

gan to rule and from where the Rus land became

to be”), but it is also possible that this monk merely

began the work that Silvestr finished. An interpo-

lation in the title of the sixteenth-century Khleb-

nikov copy has led to a popular notion that Nestor

was the name of this monk and that he had com-

pleted a now-lost first redaction of the complete

text. But that interpolation is not reliable evidence,

since it may have been the result of a guess by the

interpolator, in which case the name of the monk

referred to in the title or when he compiled his text

is not known. So the simplest explanation is that

Silvestr used an earlier (perhaps unfinished) chron-

icle by an unknown monk of the Caves Monastery

along with other sources to compile what is now

known as the PVL. Silvestr’s holograph does not

exist; the earliest copy dates to more than 260 years

later. Therefore, researches have to try to recon-

struct what Silvestr wrote on the basis of extant

copies that are hundreds of years distant from its

presumed date of composition.

There are five main witnesses to the original

version of the PVL. The term “main witness,” refers

only to those copies that have independent au-

thority to testify about what was in the archetype.

Since most copies of the PVL (e.g., those found in

the Nikon Chronicle, Voskresenskii Chronicle, etc.)

are secondary (i.e., derivative) from the main wit-

nesses, they provide no primary readings in rela-

tion to the archetype. The five main witnesses are:

1. Laurentian (RNB, F.IV.2), dated to 1377;

2. Radziwill (BAN, 34. 5. 30), datable to the 1490s;

3. Academy (RGB, MDA 5/182), dated to the 15th

century;

4. Hypatian (BAN, 16. 4. 4), dated to c. 1425;

5. Khlebnikov (RNB, F.IV.230), dated to 16th cen-

tury.

In addition, in a few places, the Pogodin Chronicle

fills in lacunae in the Khlebnikov copy:

6. Pogodin (RNB, Pogodin 1401), dated to early

17th century.

One can also draw textual evidence from the

corresponding passages in the later version of the

Novgorod I Chronicle. To date, there are no litho-

graphs or photographic facsimilies of any manu-

script of the Novgorod I Chronicle. The three copies

of the published version of Novg. I are:

1. Commission (SPb IRI, Arkh. kom. 240), dated

to 1450s;

2. Academy (BAN 17.8.36), dated to 1450s;

PRIMARY CHRONICLE

1224

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

3. Tolstoi (RNB, Tolstovoi F.IV.223), dated to

1820s.

One can also utilize certain textual readings

from the corresponding passages of Priselkov’s re-

construction of the non-extant Trinity Chronicle.

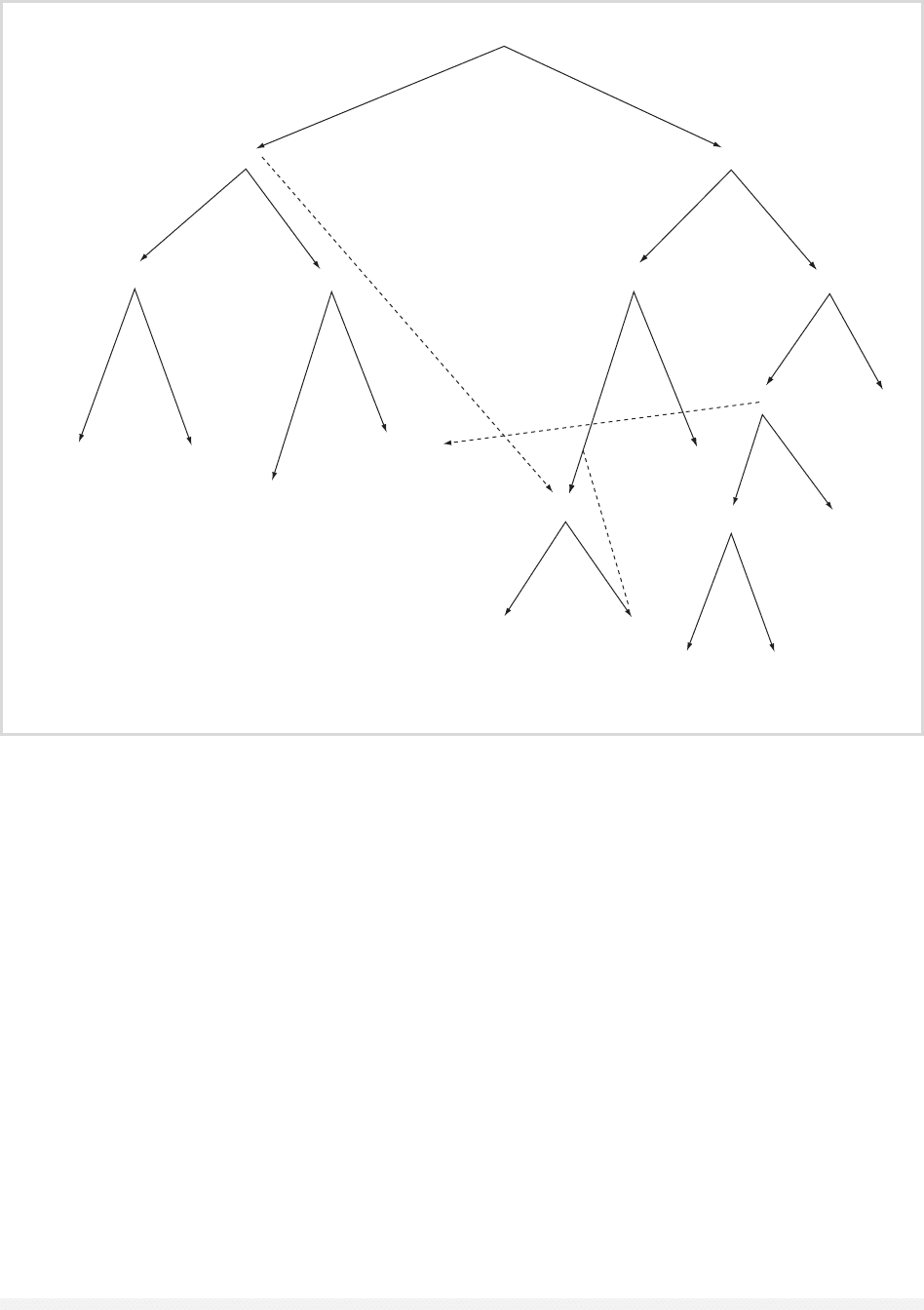

The stemma, or family tree, shows the ge-

nealogical relationship of the manuscript copies.

Although various theories have been proposed

for the stages of compilation of the PVL, little agree-

ment has been reached. The sources that the com-

piler(s) utilized, however, are generally recognized.

The main source to 842 is the Chronicle of Georgius

Hamartolu and to 948 the Continuation of Symeon

the Logothete. Accounts of the ecumenical councils

could have been drawn from at least three possible

sources: (1) a Bulgarian collection, which served as

the basis for the Izbornik of 1073; (2) the Chronicle

of Hamartolus; and (3) the Letter of Patriarch Photius

to Boris, Prince of Bulgaria. Copies of treaties between

Byzantium and Rus appear under entries for 907,

912, 945, and 971. The Creed of Michael Syncellus

was the source of the Cree d taught to Volodimir

I in 988. Metropolitan Hilarion’s Sermon on Law and

Grace is drawn upon for Biblical quotations re-

garding the conversion of Volodimir I. There are

also excerpts from the Memoir and Eulogy of

Volodimir that are attributed to the monk James.

The Life of Boris and Gleb appears in the PVL but in

a redaction different from the independent work

written by Nestor. Quotations in the PVL attrib-

uted to John Chrysostom seem to be drawn from

the Zlatoustruiu (anthology of his writings). Sub-

sequently two references are made in the PVL to

the Revelations of Pseudo-Methodius of Patara. Var-

ious parts of the PVL draw on the Paleia (a synop-

sis of Old Testament history with interpretations).

PRIMARY CHRONICLE

1225

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Figure 1.

Radziwill

Academy

(Moscow)

[Trinity]

Laurentian

Khlebnikov

Pogodin

Ermolaev

Hypatian

Tolstoi

Synod

Commission

Academy

(St. Petersburg)

ß

α

γ

δ

ε

ζ

η

θ

ι

SOURCE: Adapted from Palaeoslavica. 7:18, 1999.

In the entries for 1097 to 1100, there is a narra-

tive of a certain Vasily who claims to have been an

eyewitness and participant in the events being de-

scribed. Volodimir Monomakh’s Testament and Let-

ter to Oleg appear toward the end of the text of the

chronicle. Finally, oral traditions and legends seem

to be the basis for a number of other accounts, in-

cluding the coming of the Rus’.

Although the text of the PVL has been published

a number of times including as part of the publica-

tion of later chronicles, only recently has a critical

edition based on a stemma codicum been completed.

See also: BOOK OF DEGREES; CHRONICLES; KIEVAN RUS;

RURIKID DYNASTY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cross, Samuel H., and Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd P.

(1953). The Russian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian

Text. Cambridge, MA: Mediaeval Academy of Sci-

ences.

Ostrowski, Donald. (2003). The Povest’ vremennykh let: An

Interlinear Collation and Paradosis, 3 vols., assoc. ed.

David J. Birnbaum (Harvard Library of Early Ukrain-

ian Literature, vol. 10, parts 1–3). Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

D

ONALD

O

STROWSKI

PRIMARY PARTY ORGANIZATION

Primary Party Organization (PPO) was the official

name for the lowest-level organization in the struc-

ture of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

PPOs were set up wherever there were at least three

Party members, and every member of the Party

was required to belong to one. PPOs existed in ur-

ban and rural areas, usually at Party members’

places of work, such as factories, state and collec-

tive farms, army units, offices, schools, and uni-

versities. The highest organ of a PPO was the Party

meeting, which was convened at least once per

month and elected delegates to the Party conference

at the raion or city level. In the larger PPOs, a bu-

reau was elected for a term of up to one year to

conduct day-to-day Party business. But if a PPO

had fewer than fifteen members, they elected a sec-

retary and deputy secretary rather than a bureau.

Occupants of the post of PPO secretary or PPO bu-

reau head had to have been Party members for at

least a year. PPO secretaries were usually paid or

released from their regular work if their cell in-

cluded more than 150 Party members. Although

the PPO may seem insignificant in comparison to

the higher organs of the CPSU, it performed cru-

cial political and economic functions, such as ad-

mitting new members; carrying out agitation and

propaganda work (e.g., educating Party members

in the principles of Marxism-Leninism), and en-

suring that Party discipline was maintained. Fi-

nally, PPOs were vital to the fulfillment of Party

objectives (e.g., meeting planned quotas and pro-

duction targets).

See also: COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE SOVIET UNION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hill, Ronald J., and Frank, Peter. (1981). The Soviet Com-

munist Party. London: George Allen & Unwin.

C

HRISTOPHER

W

ILLIAMS

PRIME MINISTER

The prime minister (or premier) was the chief ex-

ecutive officer of the Soviet government. The posi-

tion was formally known as the chairman of the

Council of Ministers (also known as the Sov-

narkom, 1917–1946, and the Cabinet of Ministers,

1990–1991). The prime minister led sessions of the

Council of Ministers and the more exclusive and se-

cretive Presidium of the Council of Ministers. The

prime minister was charged with overall responsi-

bility for managing the centrally planned com-

mand economy and overseeing the extensive public

administration apparatus.

Representing one of the most powerful posi-

tions in the Soviet leadership hierarchy, the post of

prime minister carried automatic full membership

in the Politburo, the top executive body in the po-

litical system. The prime minister’s seat was fre-

quently the object of intense intra-party factional

conflicts to control the economic policy agenda.

The Soviet Union’s first prime minister was

Bolshevik Party leader Vladimir Lenin, who chaired

the Sovnarkom, the principal executive governing

body at that time. Lenin, who was not fond of ex-

tended debates, began the practice of policy mak-

ing through an inner circle of ministers. Following

Lenin’s death in 1924, the positions of government

head and Party leader were formally separated from

one another.

PRIMARY PARTY ORGANIZATION

1226

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Alexei Rykov, an intellectual with economic ex-

pertise, was appointed prime minister, overseeing

the administration of the mixed-market New Eco-

nomic Policy (NEP). In the late 1920s, as party sen-

timent turned against the NEP, leadership contender

Josef Stalin maneuvered to dislodge Rykov from

this post. Next, Prime Minister Vyacheslav Molotov,

a staunch ally of Stalin, presided over and spurred

on the ambitious and tumultuous state-led indus-

trialization and collectivization campaigns of the

1930s. In 1939, with war looming, Molotov was

dispatched to the foreign ministry, and Stalin

claimed the position, accumulating even greater

personal power.

When Stalin died in 1953, it was deemed nec-

essary once again to separate the posts of Party and

government leadership. Georgy Malenkov, who

had managed the wartime economy as de facto pre-

mier, was officially promoted to prime minister.

Malenkov attempted the diversion of resources

away from military industry to the consumer sec-

tor, but was forced to resign by political rivals. The

prime minister’s post was occupied next by Niko-

lai Bulganin, whose expertise lay in military mat-

ters. In 1958 Communist Party leader Nikita

Khrushchev appointed himself prime minister, in

violation of Party rules.

Following Khrushchev’s removal in 1964, the

prime minister’s position became more routinized

within the leadership hierarchy, though the Polit-

buro had the last say on economic policy. As in-

dustry developed and the economy grew more

complex, the responsibilities of the prime minister

became increasingly technocratic, requiring greater

command of economic issues and firsthand man-

agerial experience. Prime ministers in the late Soviet

period struggled unsuccessfully with the challenge

of devising economic strategies to regenerate growth

from the declining command economy.

Individuals holding the post of prime minister

included: Vladimir Lenin (1917–1924), Alexei Rykov

(1924–1929), Vyacheslav Molotov (1930–1939),

Josef Stalin (1939–1953), Georgy Malenkov

(1953–1955), Nikolai Bulganin (1955–1958),

Nikita Khrushchev (1958–1964), Alexei Kosygin

(1964–1980), Nikolai Tikhonov (1980–1985),

Nikolai Ryzhkov (1985–1990), and Valentin Pavlov

(1990–1991).

See also: COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE SOVIET UNION;

COUNCIL OF MINISTERS, SOVIET; POLITBURO; SOV-

NARKOM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hough, Jerry, and Fainsod, Merle. (1979). How the So-

viet Union is Governed, rev. ed. Cambridge, MA: Har-

vard University Press.

Rigby, T. H. Lenin’s Government: Sovnarkom, 1917–1922.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

G

ERALD

M. E

ASTER

PRIMITIVE SOCIALIST ACCUMULATION

Primitive Socialist Accumulation was a concept de-

veloped by the Soviet economist Yevgeny Preo-

brazhensky to analyze the New Economic Policy

(NEP) of the 1920s.

Adam Smith and other classical economists re-

ferred to “previous” or “primitive” accumulation of

capital to explain the rise of specialization of pro-

duction and the division of labor. Specialized pro-

duction required the prior accumulation of capital

to support specialized workers until their products

were ready for sale. Previous accumulation occurred

though saving, and the return to capital repre-

sented the reward for saving. Karl Marx parodied

this self-congratulatory thesis, arguing instead that

primitive capitalist accumulation represented no

more than “divorcing the producer [i.e., labor] from

the means of production.” It was the process of cre-

ating the necessary capitalist institutions: private

monopoly ownership of the means of production

and wage labor.

Preobrazhensky sought to develop a compara-

ble concept for capital accumulation in the Soviet

Union of the 1920s. The NEP meant that private

small-scale capitalist enterprises, including peasant

farms, coexisted with the state’s control of the

“commanding heights” of the economy. To attain

socialism the socialized sector had to grow more

rapidly than the private sector. Preobrazhensky

therefore set about to determine what institutional

relations were necessary to attain this end. Primi-

tive socialist accumulation was his answer.

As for capitalist accumulation, force would

need to be the agent of primitive socialist accumu-

lation, and it was to be applied by the. revolution-

ary socialist state in the form of tax, price, and

financial policies to expropriate the surplus value

created in the private sector and transfer it to the

socialist sector, thereby guaranteeing its differen-

tial growth. Under what he called “premature so-

cialist conditions” that characterized the USSR,

PRIMITIVE SOCIALIST ACCUMULATION

1227

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Preobrazhensky recommended nonequivalent ex-

change, that is, the turning of the terms of trade

against the peasantry and other private enterprises,

as the main means to collect and transfer the sur-

plus. During the transition, workers in socialist en-

terprises would experience “self-exploitation.” Over

time, therefore, primitive socialist accumulation

would eliminate the private sector.

Although the concept appears to be consistent

with Marx’s use of it in the analysis of capitalism,

Preobrazhensky’s theory was roundly criticized by

Nikolai Bukharin and other Bolshevik theorists,

probably because he used the term “exploitation”

in prescribing a socialist economic policy.

See also: MARXISM; NEW ECONOMIC POLICY; PREO-

BRAZHENSKY, YEVGENY ALEXEYEVICH; SOCIALISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Erlich, Alexander. (1960). The Soviet Industrialization De-

bate, 1921–1928. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univer-

sity Press.

Millar, James R. (1978). “A Note on Primitive Accumu-

lation in Marx and Preobrazhensky.” Soviet Studies

30(3):384–393.

Preobrazhensky, E. (1965). The New Economics, tr. Brian

Pearce. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

J

AMES

R. M

ILLAR

PRISONS

Up to the beginning of the nineteenth century

monasteries and fortresses often served as prisons

(tyurma from German turm ⫽ tower). The Russ-

ian prisons in about 1850 were mostly over-

crowded wood buildings that had not been built for

the purpose of the accommodation of prisoners,

many of whom left the prisons with destroyed

health. Russian authorities were more likely to use

other forms of punishment, such as whipping and

other corporal punishment for small offences and

hard labor and exile to Siberia for serious crimes.

As early as the eighteenth century there were fruit-

less attempts at prison reform. In 1845 the tsar

compiled a new Code of Punishments that featured

a hierarchy of incarcerations including prelim-

inerary prisons, strait houses, correctional prisons,

and punitive prisons. According to the model of the

Pentonville Prison in England, the isolation of the

prisoner was viewed as a condition for his im-

provement.

There was no uniform prison management.

Supervision was exercised by the ministry of the

interior (MVD), the Department of Justice, and the

respective governors. The public prosecutor’s office

was responsible for the well being of the prisoners.

The prison question became topical by the penal re-

form of April 17, 1863: Corporal punishment was

deemed antiquated and prison sentences became

more typical. Now for smaller offenses the pun-

ishment was up to seven days of custody. This re-

form led, therefore, to a quick increase of the prison

population and chaos in management. In the 1860s

and 1870s various committees dealt with reform

of the prison system. In 1877 a newly formed com-

mittee called Grot petitioned for a new hierarchy

of punishment with seven steps, from fines up to

the death penalty. The prisoners were to be sepa-

rated except for work details. It was suggested a

Main Prison Administration (GTU) should be es-

tablished within the Ministry of the Interior, to be

PRISONS

1228

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

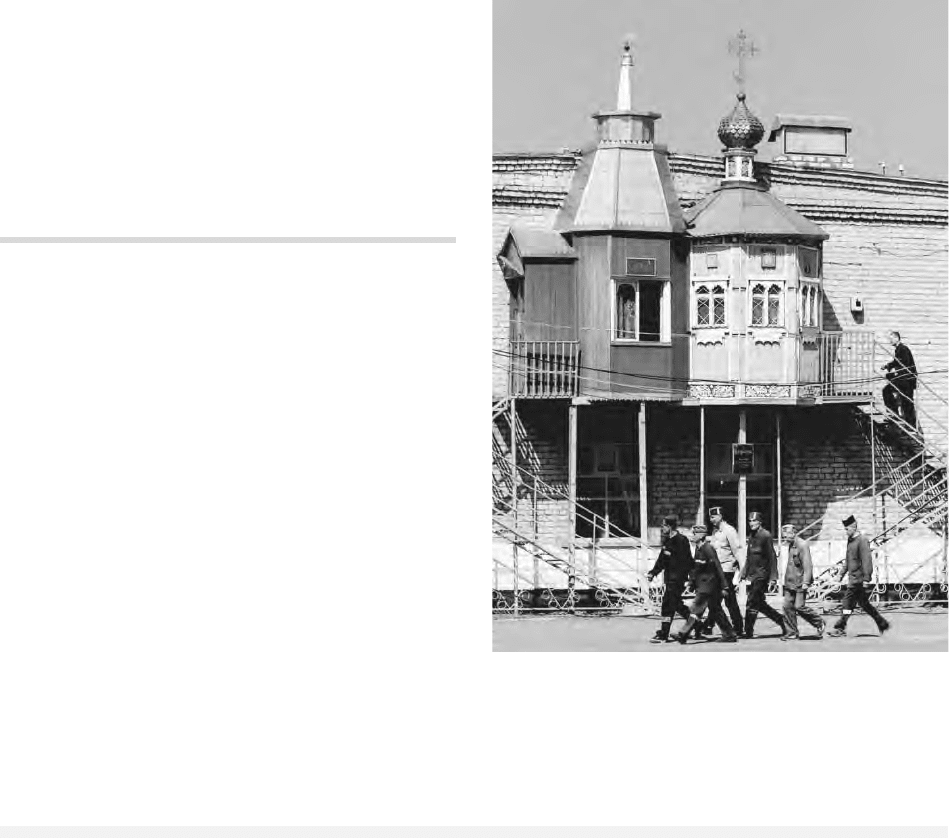

The towers of a makeshift mosque and Russian Orthodox

chapel are visible behind inmates at a prison colony in Udarny,

Russia, 2001. P

HOTOGRAPH BY

M

AXIM

M

ARMUR

/A

SSOCIATED

P

RESS

.

R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

responsible for all questions of the Russian prison

system. The suggestions of the Grot committee be-

came law on February 27, 1879. At this time there

were about seven hundred prisons with a capacity

of 54,253 inmates, but actually 70,488 persons

were housed there. In the next few decades, signif-

icant efforts were undertaken in the repair of old

prisons and the construction of new ones. Between

1879 and 1905, the GTU succeeded in improving

the conditions in the Russian prisons, during which

time, in 1895, the GTU was transferred from the

MVD to the Department of Justice. As a result of

the waves of arrests after the revolution of 1905,

the number of prisoners doubled from 1906 to

1908. After the February 1917 revolution the GTU

was renamed the Main Administration of Places of

Incarceration (GUMZ), and many prisoners who

had been granted amnesty were re-arrested.

In April 1918 the new People’s Commissioner’s

Office for Justice (NKYu) dissolved the GUMZ and

formed the Central Penal Department (TsKO). Soon

there developed in parallel to the activity of the

NKYu a system of places of incarceration of the

VChK (All-Russian Extraordinary Commission on

Struggle against Counterrevolution, Sabotage and

Speculation). In the prisons of the TsKO were

housed the usual criminals; the VChK was respon-

sible for putative and real opponents of the revo-

lution. A principal purpose of prisons was the

re-education of the delinquent; accordingly the

TsKO was renamed the Central Working Improve-

ment Department (TsITO) in October 1921. Hunger

was common in TsITO facilities.

In early 1922 the VChK was integrated into the

People’s Commissioner’s Office for Internal Affairs

(NKVD). On July 1, 1922, the handing over of all

places of incarceration from the NKYu to the NKVD

was effected and the prison management was re-

organized in the Main administration of Places of

Incarceration (GUMZ NKVD). Additionally, the se-

cret police (United State Political Administration,

OGPU) had prisons under its jurisdiction. In the

time of the Big Terror many prisoners were in

the gulag. Under the new people’s commissioner,

PRISONS

1229

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

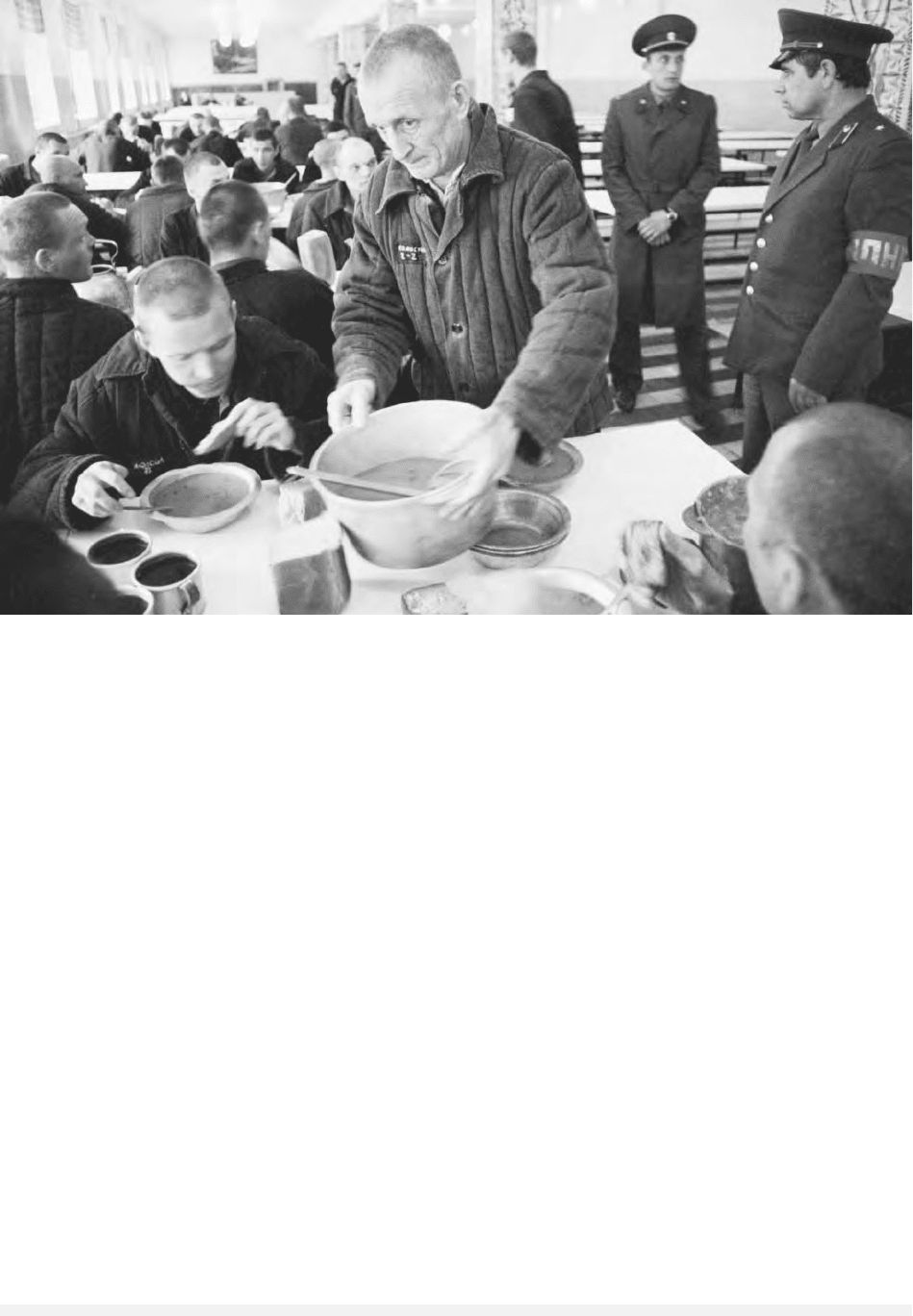

Prisoners eating in a cafeteria, Norilsk, Russia, July 1991. © D

AVID

T

URNLEY

/CORBIS

Beriya, all prisoners able to work were removed

from the prisons; in the Soviet Union after Stalin

relatively few were incarcerated.

On May 7, 1956, the MVD of the USSR issued

regulations for inmates, distinguishing between a

“general” and an “austere” regime, the latter for

prison who systematically violated regulations. On

October 8, 1997, the penal enforcement system was

subordinated by an Ukas of the president of the

Russian Federation, moving again to the Depart-

ment of Justice, where a State Administration for

the Penal Enforcement (GUIN) was founded. Re-

gardless of jurisdiction, however, the prisons con-

tinue to receive inadequate funding and, as they

were in 1850, continue to be overcrowded, with

inmates often afflicted with communicable dis-

eases.

See also: GULAG; LEFORTOVO; LUBYANKA; STATE SECU-

RITY, ORGANS OF

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adams, Bruce F. (1996). The Politics of Punishment: Prison

Reform in Russia 1863–1917. DeKalb: Northern Illi-

nois University Press.

G

EORG

W

URZER

PRISON SONGS

Given Russia’s vast prison population, prison songs

always constituted a considerable part of popular

culture. Interestingly enough, in contemporary

Russian prisons themselves, prison songs are not

as popular as is commonly thought. As experienced

prisoners explain, if the person likes to sing, he or

she may receive the nickname “Tape recorder” and

may be “turned on” at any moment, meaning that

anyone may ask him or her to sing at any mo-

ment for someone’s pleasure. This subordinate po-

sition brings down the status of the

convict who thus cannot be very popular or pres-

tigious. But in normal life outside of prison, these

songs acquired tremendous popularity starting

from the second half of the twentieth century.

Contemporary prison songs originate from the

older traditions of the sixteenth through nineteenth

centuries, such as brigand songs of those in active

opposition to the state and social authorities,

drawling songs of hard-labor convicts, and thieves’

cant as a creature of urban environment closely re-

lated to the genre of city romance. The latter be-

came widespread at the turn of the twentieth

century due to rapid social changes and marginal-

ization of Russian society in the years of the Rev-

olution. The most popular song of the period,

Murka, tells a dramatic story of an undercover po-

licewoman killed by her criminal lover for her be-

trayal.

From the second half of the twentieth century,

prison songs occupied a leading position in Soviet

underground culture. In the 1960s the most popu-

lar bards, such as Vladimir Vysotsky, Alexander

Galich, and others, attracted intelligentsia by singing

prison songs, thus giving a form of expression of

hidden protest against the regime. In their songs

prison is associated with the state as a whole; it is

implied that under this regime everone is a convict,

whether past, present, or future. Rich metaphorical

content, antistate motivation, and strong heroic po-

etics made these songs the sign of the time when the

truth about the regime became known with gulag

prisoners first being rehabilitated after Stalin’s death.

This tradition stems from the political, not the crim-

inal, environment and was closely connected to the

dissident movement of the time.

In contrast to the dissident content of prison

songs of the 1960s and 1970s, contemporary

prison songs emphasize the criminal element more

and are targeted at a specific audience with a clear

criminal past and present. Recently these songs suc-

cessfully entered the popular music industry. These

songs are based on the most popular genre of con-

temporary prison folklore such as ballads. Most of

them are “humble” songs: They aim at compassion

for the lot of any marginal personality, such as

thieves, prostitute, and social outcasts. Their sub-

ject is misery, tragic accident, or cruel destiny. Sev-

eral verses of the ballad cover the entire life of the

hero with its happiness, tears, love and betrayal,

crime, and custody. Another type of song, by con-

trast, aims to unite people who share asocial val-

ues as a group claiming brotherhood and heroism

of a few against conventional authorities.

See also: DISSIDENT MOVEMENT; GULAG; PRISONS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Stites, Richard. (1992). Russian Popular Culture: Enter-

tainment and Society since 1900. New York: Cam-

bridge University Press.

J

ULIA

U

LYANNIKOVA

PRISON SONGS

1230

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

PRIVATIZATION

Privatization may be pursued with different aims

in mind. The political aim is to break away from

the past and create a new class of capitalists as

quickly as possible. The efficiency aim is to create a

better management system for the enterprises, and

to set up a market environment. If this aim is dom-

inant, it requires complex institution-building and

thus precludes rapid completion of the process. Pri-

vatization may have a financial aim: in this case

the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) should be sold

at their highest value so as to bring revenues to the

state. Finally, an equity aim may involve returning

property to those who had been deprived of it by

the nationalization process (an aim pursued in

some Central European countries), giving priority

to employees for buying shares in their enterprises,

or even giving away state assets to the citizens.

In Russia, privatization began in January 1992,

together with the implementation of the stabiliza-

tion program, and assumed the form of liberaliza-

tion of small-scale trade (street vending). This

“small privatization” was conducted at a quick pace

in the services sector, which consisted of trade,

catering, services to households, construction, in-

dividual transportation activities, and housing. It

was often marred by racketeering and crime. The

small-scale state enterprises (which had already

been transferred to the local authorities in 1991)

were sold to citizens, local entrepreneurs, and/or

employees, basically through auctions. At the same

time, as prices and individual activities were liber-

alized, it became immediately possible to create

new, small-scale businesses, especially in fields

where human capital was the main requirement,

such as consulting, engineering, private teaching,

and computer services. Actually, such activities

were already privately conducted in the Soviet era

within the shadow economy.

The main challenge lay in the privatization of

the big SOEs, or large-scale privatization. The Russ-

ian government was clearly privileging the politi-

cal objective, and hence opted for a quick mass

privatization scheme. It also favored equity con-

siderations, so that the people would benefit from

the divestment of the state. In June 1992, the mass

privatization program was adopted, and in Octo-

ber the voucher system was launched. All Russian

citizens received 10,000 rubles’ worth of privati-

zation vouchers (equivalent then to 50 U.S. dollars),

immediately redeemable in cash, or exchangeable

against shares in the enterprises selected for priva-

tization that had been transformed into joint stock

companies. These enterprises were sold at direct

public auctions. The staff (employees and manage-

ment) could opt for three variants, of which the

most popular was the allocation of 51 percent of

the shares to the employees at a discounted price.

Seventy percent of the enterprises were thus pri-

vatized by the end of June 1994; past this deadline

the vouchers were no longer valid. The second wave

of large-scale privatization proceeded much more

slowly and was far from complete in 2002. It had

to be based upon sales to foreigners or domestic

buyers. It was slowed by several factors: the Russ-

ian financial crisis of 1998, which led to a collapse

of the banking sector; the scandals linked with the

outcomes of the first wave, when several notori-

ous deals evidenced the dominant role of insiders

who managed to acquire large assets with very

little cash; and, finally, the enormous stakes of

the second wave, which involved privatization of

the energy sector (oil, gas, and electricity) and the

telecommunications sector.

Who owned the Russian enterprises? The most

prominent owners were the oligarchs, who con-

trolled the largest firms of the energy and raw ma-

terials sector, but who became less powerful after

Boris Yeltsin’s resignation in 1999. More generally,

the former nomenklatura of the Soviet system,

along with a small number of newcomers, took ad-

vantage of a privatization process lacking trans-

parency and clear legal rules. Restructuring of

enterprises and improving of corporate governance

did not proceed along with the change in owner-

ship. Privatization was close to completion in Rus-

sia as of 2002, when 75 percent of the GDP was

created by the private sector. However, the private

sector had yet to function according to the rules of

a transparent market.

See also: ECONOMY, POST-SOVIET; LIBERALISM; SHOCK

THERAPY; TRANSITION ECONOMIES.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Boycko, Maxim; Shlejfer, Andrei; and Vishny, Robert.

(1995). Privatizing Russia. Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press.

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

(EBRD). (1999). Transition Report 1999: Ten Years of

Transition. London: EBRD.

Hedlund, Stefan. (2001). “Property Without Rights: Di-

mensions of Russian Privatisation.” Europe-Asia

Studies 53(2):213–237.

M

ARIE

L

AVIGNE

PRIVATIZATION

1231

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

PROCURACY

The prosecutor’s office in the Russian Federation

plays a pivotal role in law enforcement, including

criminal investigations and prosecution, represen-

tation of the state’s interests in civil disputes, su-

pervision of the functioning of prisons and places

of detention, and investigation of citizens’ griev-

ances.

The Procuracy was introduced in 1722 by Pe-

ter the Great in an effort to create a public law sys-

tem similar to those in Western Europe. However,

in practice, the Procuracy focused primarily on su-

pervising the prompt and full execution of the

tsar’s edicts. Catherine II extended procuratorial su-

pervision to regional and local levels, where procu-

rators served as the “eyes of the tsar” in monitoring

the activity of provincial governors and other of-

ficials. This function was widely resented by

provincial governors and was eliminated by the le-

gal reforms of 1864.

A decree of November 24, 1917, of the Coun-

cil of People’s Commissars abolished the Procuracy

and all other tsarist legal institutions in favor of

more informal control mechanisms. In 1922 the

Bolshevik government reestablished the Procuracy

to serve as the “eyes of the state,” insuring full and

complete cooperation in executing the policies of

the state and the Communist Party.

During the Stalin era the Procuracy, under the

leadership of Procurator-General Andrei Vyshin-

sky, aggressively pursued suspected opponents of

Stalin’s regime and secured their speedy imprison-

ment or execution. The Procuracy’s jurisdiction

was also extended to non-legal matters, such as

overseeing the successful implementation of indus-

trialization and collectivization.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, the Procuracy

shifted its emphasis from coercion and repression

to prosecuting ordinary criminals and supervising

legality in the operations of various governmental

agencies. The Procuracy grew in power and pres-

tige during the post-Stalin period. By the 1980s it

employed more than 18,000 lawyers and super-

vised an additional 18,000 criminal investigators;

together they comprised more than one-quarter of

the Soviet Union’s legal profession.

Prosecutors were slow in responding to Gor-

bachev’s reforms, viewing them as a threat to their

wide-ranging authority. The Procuracy managed

to defend its privileged position in the Russian le-

gal system even after the demise of the USSR. A

new “Law on the Procuracy of the Russian Feder-

ation” was enacted in 1995. The law enshrined the

Procuracy as a single, unified, and centralized in-

stitution charged with “supervising the implemen-

tation of laws by local legislative and executive

bodies, administrative control organs, legal entities,

public organizations, and officials, as well as the

lawfulness of their acts.” While the Procuracy’s ju-

risdiction remained broad, it lost power to super-

vise the operation of the courts, which was

transferred to the Ministry of Justice.

The powers of the Procuracy have been further

restricted by the new criminal procedure code,

which was enacted in July 2002. According to the

code, prosecutors may no longer issue search war-

rants or order suspects to be detained. In addition,

prosecutors must appear in court to present the

state’s case, rather than rely on an extensive dossier

compiled during the preliminary investigation.

These and other restrictions were undertaken to

limit the Procuracy’s privileged status in criminal

prosecutions, engender a more adversarial process,

and elevate the status and independence of the

courts.

See also: LEGAL SYSTEMS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mikhailovskaya, Inga. (1999). “The Procuracy and Its

Problems.” East European Constitutional Review

11:1–2.

Smith, Gordon B. (1978). The Soviet Procuracy and the Su-

pervision of Administration. Alphen aan den Rijn,

Netherlands: Sijthoff & Noordhoff.

Smith, Gordon B. (1996). Reforming the Russian Legal Sys-

tem. New York: Cambridge University Press.

G

ORDON

B. S

MITH

PRODNALOG

“Food Tax.”

The word prodnalog comes from the nouns

“food” (prodovolstvie) and “tax” (nalog). It is trans-

lated as “food tax,” or “tax in kind.” The food tax

was an instrument of state policy to collect food

and was used twice during the Soviet period. The

first introduction of the food tax was in 1921, dur-

ing the period of the New Economic Policy (NEP).

During the period of war communism (1918–1921),

the Soviet state used forced requisitions to confis-

PROCURACY

1232

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY