Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

“False Dmitry,” who claimed to be Ivan IV’s son

and triumphantly entered Moscow in 1605. In

great part because of the large Polish retinue and

openly Catholic sympathies of “Dmitry,” he was

soon deposed and murdered. But Polish interference

in confused Muscovite politics continued. Most

spectacularly, King Sigismund III of Poland suc-

ceeded in having his son Wladyslaw proclaimed

tsar in 1610. The Polish presence in Moscow was

not to last; by 1613 the Poles had been slaughtered

or forced to flee, and Mikhail Romanov was elected

tsar.

As Russia recovered and expanded under the

Romanovs, Poland grew weaker. Poland’s highly

decentralized government and elected king meant

that the central government could not impose its

will on the provinces. Increasingly, power devolved

to the local magnates, further weakening the cen-

ter. The anti-Polish rebellion of Bohdan Khmelnit-

sky in 1648 allowed Muscovy to extend its power

into the Ukraine with the Treaty of Pereiaslavl

(1654). Additional Polish territory, including the

cities of Smolensk and Kiev, was lost to the Rus-

sians during the following decade.

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

The eighteenth century witnessed further Polish de-

scent into anarchy. Already during the 1690s Pol-

ish king Jan Sobieski had complained of his

inability to force the Polish magnates to obey him.

Worse was to come. The fact that Polish kings were

elected allowed Poland’s neighbors to put up their

own candidates in the hope of influencing future

policy. Poland also had the misfortune to be placed

geographically between three rising absolutist

states—Prussia, Russia, and Habsburg Austria. In

1764, St. Petersburg succeeded in placing its can-

didate on the Polish throne. Stanisl

-

aw-August

Poniatowski, a former lover of Catherine the Great,

was to be the last Polish king.

PARTITIONS AND RUSSIAN RULE

The impetus toward partition came not from Rus-

sia, but from Poland’s western neighbor, Prussia.

That state’s ambitious ruler, Frederick II (“the

Great”) suggested a dividing up of Polish territory

to prevent destabilizing “anarchy.” In the first Par-

tition of Poland (1772), Russia absorbed some thir-

teen percent of the commonwealth’s territory. The

shock of the partition fueled a push for serious po-

litical reforms, including a strengthening of the

central government and the king. The partitioning

powers, including Russia, feared a strong Poland.

They were particularly disturbed by the fruitful ef-

forts of the Four-Years-Sejm, including the Polish

constitution of May 3, 1791. Once again using the

excuse of Polish anarchy, Prussia and Russia seized

more Polish territory in the Second Partition of

1793, calling forth a Polish national uprising.

However, the heroic efforts of insurrectionist

Tadeusz Kosciuszko could not prevent the Third

Partition of 1795, after which Poland disappeared

from the European map for more than a century.

After the Napoleonic wars, borders between the

partitioning powers were altered significantly,

bringing a large portion of ethnic Poland under

Russian rule. The majority of Poles thus became

subjects of the Russian tsar. Tsar Alexander I af-

forded the Kingdom of Poland considerable rights

and autonomy. The Poles enjoyed their own

coinage, legal system, army, legislature, and con-

stitution. Disagreements between Warsaw and St.

Petersburg over the limits of Polish autonomy ex-

ploded into the open during the November Upris-

POLAND

1193

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

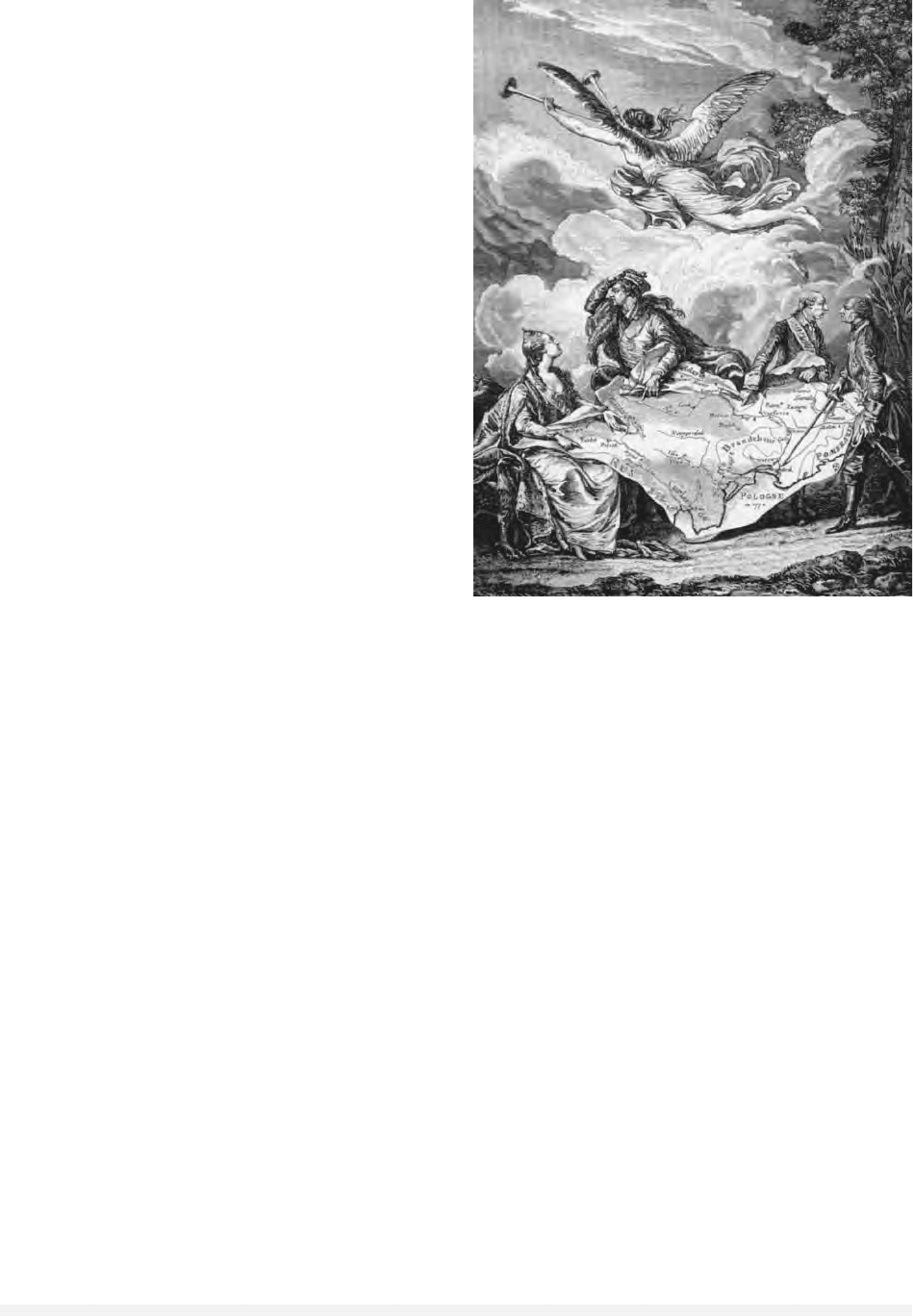

A 1772 drawing shows Polish King Stanislav trying to hold onto

his crown while Poland is split between Catherine II and

Frederick II. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

ing of 1830, which lasted well into the following

year. After Nicholas I put down this insurrection,

he abolished the Kingdom of Poland’s legislature,

constitution, and army. Still, legal and adminis-

trative differences existed between Russian and Pol-

ish provinces—though these differences would be

considerably narrowed after the crushing of the

subsequent January 1863 uprising.

The final half century of Romanov rule over

much of historic Poland has generally been char-

acterized as a period of Russification. Certainly, St.

Petersburg viewed Poles en masse as at least po-

tentially disloyal subjects, and Polish culture was

kept on a very tight leash. Poles in the Russian Em-

pire could not use their native tongue in education

at any level except the most elementary—and even

here Russian was often introduced. In the so-called

Western Provinces (present-day western Ukraine,

Lithuania, Belarus) even speaking Polish in public

could lead to fines or worse. Still, there was no sys-

tematic attempt to Russify the Polish nation in the

sense of total cultural (or religious) assimilation.

Rather, Russification amounted to a severe limiting

of Polish civil and cultural rights in this period.

WORLD WAR I AND INDEPENDENCE

The outbreak of World War I transformed relations

between the partitioning powers and Poles. Now

securing the loyalty of Poles became a paramount

consideration for both Russia and the Central Pow-

ers. The Russian commander-in-chief, Grand Duke

Nikolai Nikolayevich, issued a manifesto in mid-

August 1914, holding out the postwar promise of a

unified Polish state under the Romanov scepter. In

the end, force of arms decided the issue: By autumn

1915 Russian armies had for the most part been

pushed out of ethnic Poland. With the Bolsheviks’

coming to power in October 1917 and the subsequent

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 1918), all hopes

of continued Russian—or Soviet—domination over

Poland came to an end. In late 1918 Poland regained

its independence.

Relations between Poland and the fledgling So-

viet state got off to a very bad start. Moscow was

POLAND

1194

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

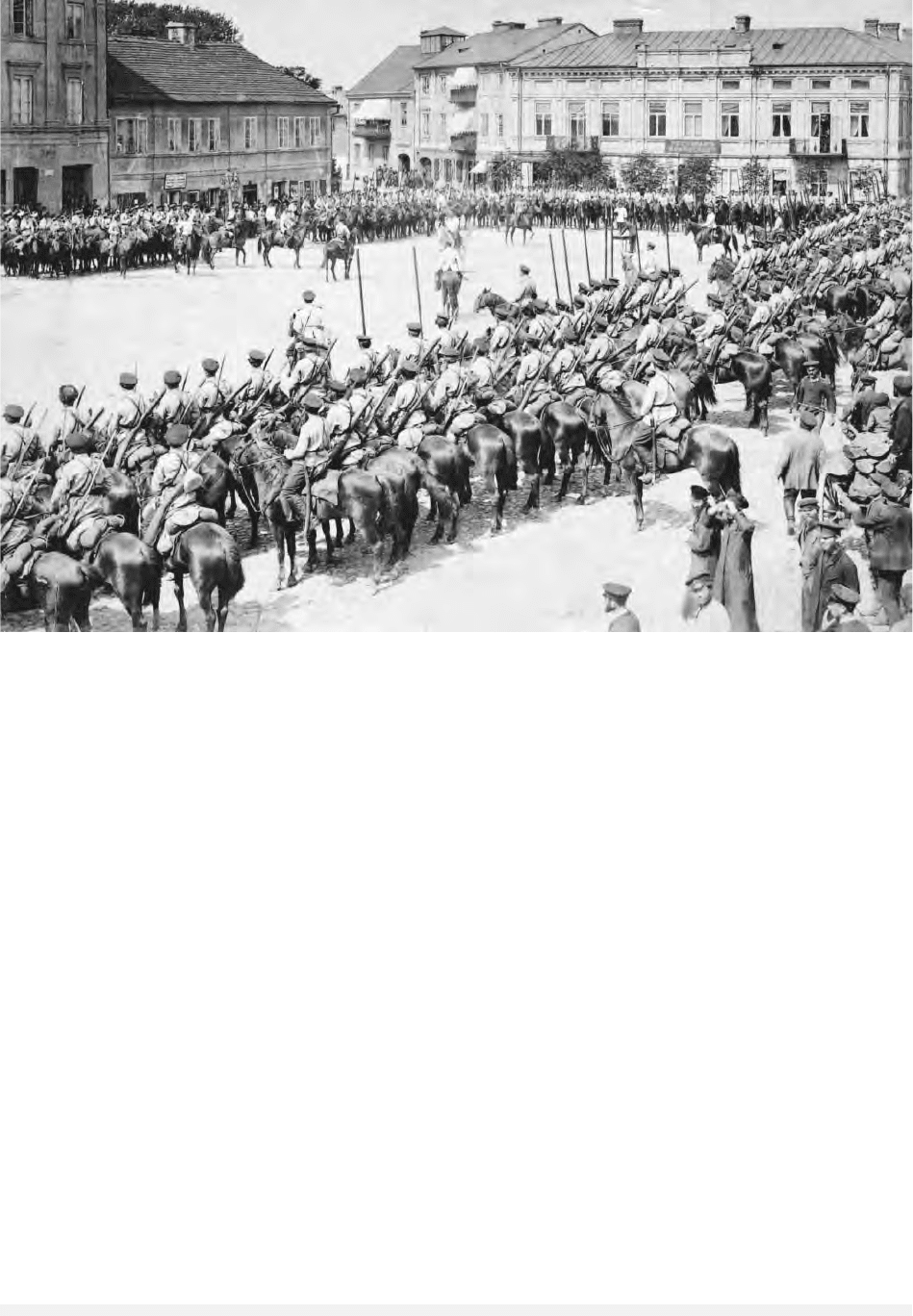

Russian troops in Warsaw after the January insurrection of 1863–1864. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

vitally interested in exporting revolution to West-

ern Europe, most likely by way of Poland. Further,

the unclear borders between Poland and its neigh-

bors to the east presented a serious potential for

conflict. Historically, Poles had been very promi-

nent as landowners and townspeople in these

border regions between ethnic Poland and ethnic

Russia. Thus Poles figure in early Soviet propa-

ganda as portly mustachioed noblemen bent on en-

slaving Ukrainian or Belarusian peasants. Between

1919 and 1921 Soviet Russia and newly indepen-

dent Poland clashed on the battlefield, the Poles oc-

cupying Kiev and, at the opposite extreme, the Red

Army getting all the way to the Vistula River in

central Poland. In March 1921, both sides, ex-

hausted for the moment, signed the Peace of Riga.

The USSR was not satisfied with the treaty’s

terms. In particular, hundreds of thousands of eth-

nic Belarusians and Ukrainians ended up on the Pol-

ish side of the frontier, providing the USSR with a

would-be constituency for extending the border

westward. Nor did relations between Poland and

the USSR improve in the interwar period. The two

primary politicians of interwar Poland, Józef

Pil

-

sudski and Roman Dmowski, both despised and

feared the Soviet state. The Communist Party was

outlawed in Poland, and many Polish communists

fled to the USSR, often straight into the Gulag. Even

Adolf Hitler’s coming to power in 1933 did not

bring the USSR and Poland closer. Rather, the later

1930s witnessed the Great Purges in the USSR and

a downward spiral in Polish politics toward an in-

creasingly vicious form of Polish chauvinism and

official anti-Semitism.

Poland was stunned by the Molotov-Ribben-

tropp Pact of August 1939. This agreement be-

tween Josef Stalin’s USSR and Hitler’s Germany

demonstrated that their mutual enmity toward the

Polish state outweighed ideological differences. The

pact allowed Hitler to invade on September 1, 1939,

and the Red Army, following a secret protocol, oc-

cupied eastern Poland later that month. Once again

Poland disappeared from the map. When the Pol-

ish state was resurrected in 1945, it was devastated.

The large and vibrant Polish Jewish community

had been all but wiped out during the Holocaust,

some three million non-Jewish Poles had lost their

lives, and the capital city Warsaw was a waste-

land, systematically destroyed by the Germans in

retaliation for the Warsaw Uprising of August

1944. Polish nationalists and some Western writ-

ers contend that the Red Army, by that time near-

ing the eastern outskirts of the city, could have

prevented the Nazi devastation of the city. Others

argue that the Red Army had been successfully re-

pulsed by the Germans. In any case, the failure of

the Soviets to move into Warsaw allowed the Nazis

to massacre Polish fighters who might very well

have opposed the imposition of communist rule.

PEOPLE’S POLAND

Having liberated Poland from the Nazis, Stalin was

determined to see a pro-Soviet government installed

there. Despite the tiny number of native Polish

communists and little support for communist or

pro-Soviet candidates, intimidation and rigged vot-

ing placed a Stalinist Polish government, led by

Bolesl

-

aw Bierut, in power in 1948. Bierut launched

a crash industrialization drive, attempted to collec-

tivize Polish agriculture, and jailed many Catholic

clergymen. After Bierut’s death in 1956, leadership

passed to the more flexible Wladyslaw Gomulka

who allowed Poles a considerable amount of cul-

tural and economic leeway while reassuring Moscow

of People’s Poland’s stability.

Unfortunately for Gomulka, Poles compared

their economic and cultural situation not with that

in the USSR, but with conditions in the West. As

the 1960s progressed, the relative backwardness of

Poland compared with Germany or the United

States only increased. Domestically, internal party

tensions led to an ugly state-sponsored anti-Semitic

episode in 1968, during which Poland’s few re-

maining Jews—most highly assimilated—were

hounded out of the country. Thus, Gomulka’s po-

sition was already weak before the notorious price

hikes on basic foodstuffs of December 1970 that

led to rioting and his replacement by Edward

Gierek. Gierek promised prosperity, but was never

able to deliver. In 1980, price increases caused civil

disturbances and his resignation.

The discontent of 1980 also spawned some-

thing quite new: the Polish trade union Solidarity.

This first independent trade union in a communist

bloc country appeared in late 1980, was banned

just more than one year later, and was resurrected—

more properly, relegalized—during the late 1980s.

Solidarity represented a novel phenomenon for

a People’s Democracy: a popular and independent

trade union that brought together intellectuals and

workers. The outlawing of Solidarity by General

Wojciech Jaruzelski in December 1981 was a des-

perate measure taken, according to Jaruzelski him-

self, to forestall an actual Soviet invasion of the

country. One may doubt Jaruzelski’s account, but

POLAND

1195

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

tensions between the USSR and Poland certainly ran

high, and the threat of invasion cannot be entirely

discounted. Ultimately, however, Jaruzelski’s at-

tempt to save People’s Poland failed. Early in 1989

Solidarity was relegalized and in summer of that

year the communists handed over power to Tadeusz

Mazowiecki, the first noncommunist prime minis-

ter since the 1940s. The refusal of Soviet leader

Mikhail Gorbachev to intervene in Polish affairs

made possible this peaceful transfer of power.

Relations between Poland and Russia during the

1990s have been remarkably positive, considering

the amazing changes brought by that decade. De-

spite grumbling and even saber rattling from

Moscow over Poland’s plans to join the North At-

lantic Treaty Organization (NATO), in the end

NATO expansion took place in 1999 without a

hitch. At the same time, economic and cultural

links between Moscow and Warsaw have weak-

ened considerably as Poland has turned toward the

West both institutionally (NATO, European Union)

and culturally (learning English instead of Russ-

ian). Still, the correct if not always cordial relations

between the two countries during the 1990s give

reason for hope that the two largest Slavic nations

will finally be able to both live together and pros-

per.

See also: CATHOLICISM; LITHUANIA AND LITHUANIANS;

NATIONALISM IN THE SOVIET UNION; NATIONALISM

IN TSARIST EMPIRE; ORGANIC STATUTE OF 1832; POLES;

POLISH REBELLION OF 1863; POLISH-SOVIET WAR; SAR-

MATIANS; TIME OF TROUBLES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Davies, Norman. Heart of Europe: A Short History of

Poland. (1984). Oxford, UK: Oxford University

Press.

Gross, Jan. (1988). Revolution from Abroad: The Soviet Con-

quest of Poland’s Western Ukraine and Western Be-

lorussia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jedlicki, Jerzy. (1999). A Suburb of Europe: Nineteenth-

Century Polish Approaches to Western Civilization. Bu-

dapest: Central European University Press.

Polonsky, Antony. (1972). Politics in Independent Poland

1921–1939: The Crisis of Constitutional Government.

Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Snyder, Timothy. (2003). The Reconstruction of Nations:

Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999. New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Walicki, Andrzej. (1991). Russia, Poland, and Universal

Regeneration: Studies on Russian and Polish Thought of

the Romantic Epoch. Notre Dame, IN: University of

Notre Dame Press.

Wandycz, Piotr. (1974). The Lands of Partitioned Poland,

1795–1918. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

T

HEODORE

R. W

EEKS

POLAR EXPLORERS

From its earliest days, Russia was concerned with

Arctic settlement and development. Actual explo-

ration began during the eighteenth century and

continued, although Russia took little part in the

classic race for the North and South poles. Interest

heightened after 1920, as the USSR transformed it-

self into a key player in North polar exploration.

After 1956, the USSR became an important force

in Antarctic research.

Russian migration to the Arctic coast began

during the eleventh century. Further settlement

was tied to the foundation of religious communi-

ties (such as the Solovetsky Monastery, built in

1435); demand for furs and precious metals; the

search for the Northeast Passage (in Russian, the

Northern Sea Route); the establishment of ports

such as Arkhangelsk (1584); and Russia’s eastward

expansion into Siberia during the sixteenth and sev-

enteenth centuries.

Scientific and exploratory work got underway

during the 1700s and 1800s. On behalf of the Russ-

ian government, Danish captain Vitus Bering, with

Alexei Chirikov as his second-in-command, launched

his Kamchatka (1728–1730) and Great Northern

(1733–1749) expeditions. Afterward, the Admi-

ralty and Academy of Sciences sponsored many

voyages and expeditions, surveying or exploring

Spitsbergen, Novaya Zemlya, the New Siberian Is-

lands, Wrangel Island, and Franz Josef Land. The

colonization of Alaska and incorporation of the

Russian-American Company (1799) necessitated

greater familiarity with the Arctic. Key figures

from this period include Fyodor Rozmyslov (d.

1771), Vasily Chichagov (1726–1809), Matvei

Gedenshtrom (1780–1843), Academy of Sciences

president Fyodor Litke (1797–1882), and Alexan-

der Sibiryakov (1844–1893). The latter sponsored

the first successful crossing of the Northeast Pas-

sage: Adolf Erik Nordenskjold’s 1878–1879 voyage

in the Vega.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, as in-

ternational audiences thrilled to the daring exploits

POLAR EXPLORERS

1196

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

of explorers like Peary and Scott, Russian polar

work focused on scientific, commercial, and mili-

tary concerns. Admiral Stepan Makarov formed a

Russian icebreaker fleet, while naval officer Alexan-

der Kolchak, later famous as a White commander

during the Russian civil war, explored the Arctic.

Early twentieth-century expeditions under Ernst

Toll, Vladimir Rusanov, Georgy Brusilov, and

Georgy Sedov ended in tragedy. By contrast, in

1914, Yan Nagursky became the first pilot suc-

cessfully to fly an airplane above the Arctic Circle.

In 1914–1915, Boris Vilkitsky completed the sec-

ond traversal of the Northeast Passage.

Under the Soviet regime, polar exploration and

development fell to agencies such as the All-Union

Arctic Institute (VAI) and, after 1932, the Main Ad-

ministration of the Northern Sea Route (GUSMP).

Prominent Arctic scientists included Vladimir Vize,

Georgy Ushakov, and Rudolf Samoilovich of the

VAI, as well as Otto Shmidt, head of GUSMP. The

USSR made impressive headway during the 1920s

and 1930s in building an economic and trans-

portational infrastructure in the polar regions. This

was also an era of spectacular public triumphs, in-

cluding the rescue of Umberto Nobile and the crew

of the dirigible Italia (1928); participation in the

Arctic flight of the airship Graf Zeppelin (1931); the

Sibiryakov’s first single-season crossing of the North-

east Passage (1932); the airlift of the Chelyuskin’s

crew and passengers, who survived two months

on the Arctic ice after their ship sank (1933–1934);

the flights of Valery Chkalov and Mikhail Gromov

over the North Pole on their way to the United

States (1937); the first airplane landing at the

North Pole (1937); and the establishment of the

first research outpost at the North Pole, the SP-1,

under the leadership of Ivan Papanin (1937–1938).

In 1941 the Soviets also accomplished the first air-

plane landing at the Pole of Relative Inaccessibility.

There was, of course, an ugly underside to Soviet

achievement in the Arctic: Not only was much So-

viet polar work characterized by inefficiency and

periodic mishaps, both major and minor, but it was

closely linked to the steady expansion of forced la-

bor in the GULAG system.

Soviet polar exploration resumed after World

War II. A new generation of researchers, including

A.A. Afanasyev, Vasily Burkhanov, Mikhail So-

mov, Alexei Treshnikov, Boris Koshechkin, and

others, came to the forefront. A second North Pole

outpost (SP-2) was established in 1950, and until

the late 1980s, the USSR operated at least two SP

stations at any given time. In 1977, the atomic ice-

breaker Arktika became the first surface vessel to

reach the North Pole.

As for the Antarctic, Russian mariners Fabian

Bellingshausen (1770–1852) became, in 1820, one

of the first three explorers knowingly to sight the

Antarctic continent (the first person to sight

Antarctica remains a matter of debate). The USSR

did not engage in serious exploration of the Antarc-

tic until 1956. During the International Geophys-

ical Year of 1957–1958, the USSR was one of

twelve nations to establish stations in Antarctica.

In 1959, the USSR signed the Antarctic Treaty,

which went into effect in 1961. As with the Arc-

tic, the collapse of the USSR in 1991 made it diffi-

cult for the Russians to continue Antarctic research,

although Russia still maintains stations there year-

round.

See also: BERING, VITUS JONASSEN; CHIRIKOV, ALEXEI

ILICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Armstrong, Terence. (1958). The Russians in the Arctic.

London: Methuen.

Armstrong, Terence. (1965). Russian Settlement in the

North. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

McCannon, John. (1998). Red Arctic: Polar Exploration

and the Myth of the North in the Soviet Union,

1932–1939. New York: Oxford University Press.

Taracouzio, T. A. (1938). Soviets in the Arctic. New York:

Macmillan.

J

OHN

M

C

C

ANNON

POLES

The Poles represent the northwestern branch of the

Slavonic race. They speak Polish, a member of the

Western Slavic branch of the Indo-European lan-

guage family. It is most closely related to Be-

lorussian, Czech, Slovak, and Ukrainian. From the

very earliest times the Poles have resided on the ter-

ritory between the Carpathians, Oder River, and

North Sea. Bolesl

-

aw I “Chrobny” or the Brave

(967–1025) united all the Slavonic tribes in this re-

gion into a Polish kingdom, which reached its

zenith at the close of the Middle Ages and slowly

declined during the mid to late eighteenth century.

Hostility to Polish nationalism formed a common

bond between the Russian, Prussian, and Austrian

governments. Thus, Poland was partitioned four

POLES

1197

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

times. The first partition (August 1772) divided

one-third of Poland between the three above-named

countries. The second partition (January 1793)

was mostly to the advantage of Russia; Austria did

not acquire land. In the third partition (October

1795), the rest of Poland was divided up between

the three autocracies. After the defeat of Napoleon

and collapse of his puppet state, the Grand Duchy

of Warsaw (1807–1814), a fourth partition oc-

curred (1815), by which the Russians pushed west-

ward and incorporated Warsaw. Until then

Warsaw had been situated in Prussian Poland from

1795 to 1807. Potent anti-Russian sentiment has

long prevailed among the Poles who are predomi-

nantly Catholic, especially during the eighteenth

and nineteenth centuries, as evidenced by four pop-

ular uprisings against the Slavic colossus to the

east: 1768, 1794, 1830–1831, and 1863. Accord-

ing to the 1890 census about 8,400,000 Poles

resided in the Russian Empire.

Finally in 1918, an independent Poland was re-

constituted. Later in August 1939 a pact was signed

between Adolf Hitler’s Germany and Josef Stalin’s

Soviet Union, which contained a secret protocol au-

thorizing yet a fifth partition of Poland: “In the

event of a territorial and political rearrangement of

the areas belonging to the Polish state the spheres

of influence of Germany and the USSR shall be

bounded approximately by the line of the rivers

Narew, Vistula, and San.” The next month Hitler’s

Germany invaded Poland; the Red Army did not in-

terfere.

After more than four decades of the Cold War,

during which Poland was a Soviet “satellite” and be-

longed to the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact, partially free

elections were held in 1989. The Solidarity move-

ment won sweeping victories; Lech Wal

-

esa became

Poland’s first popularly elected post-Communist

president in December 1990. In 1999 Poland joined

the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, along with

Hungary and the Czech Republic. It is scheduled to

enter the European Union in 2004.

See also: NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, TSARIST; POLAND

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Connor, Walter D., and Ploszajski, Piotr. (1992). The Pol-

ish Road from Socialism: The Economics, Sociology, and

Politics of Transition. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Hunter, Richard J., and Ryan, Leo. (1998). From Autarchy

to Market: Polish Economics and Politics, 1945–1995.

Westport, CT: Praeger.

Lukowski, Jerzy, and Zawadzki, Hubert. (2002). A Con-

cise History of Poland. New York: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Michta, Andrew A. (1990). Red Eagle: The Army in Polish

Politics, 1944–1988. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institu-

tion Press.

Snyder, Timothy. (2003). The Reconstruction of Nations:

Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999. New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

POLICE See STATE SECURITY, ORGANS OF.

POLISH REBELLION OF 1863

After decades of harsh limits on Polish autonomy,

many Poles were hopeful that the situation would

improve after the 1855 coronation of Alexander II.

There were indeed concessions: Martial law was

lifted, an amnesty was declared for all political pris-

oners, a new Archbishop of Warsaw was named

(the position had been vacant since 1830), and cen-

sorship was made somewhat less restrictive. In

1862 a Pole named Aleksander Wielopolski was

made governor of the Polish Kingdom, in an at-

tempt to cooperate with the aristocratic elite and

marginalize more radical national separatists and

democratic revolutionaries. All these attempts at

conciliation failed, as patriotic demonstrations broke

out in late 1861 and intensified throughout 1862.

The Russians tried to suppress these protests with

deadly force, but that only generated more anger

among the Poles, and the unrest spread.

Wielopolski tried to quash the disturbances on

the night of January 23 by organizing an emer-

gency draft into the army targeted at the young

men who had been leading the demonstrations.

This, too, failed, as it prompted the national move-

ment leaders to proclaim an uprising (which was

being planned in any case). The rebels proclaimed

the existence of the “Temporary National Govern-

ment,” which would lead the revolt and (they

hoped) pave the way for a true independent Polish

government afterwards.

The “January Uprising” (as it is known in

Poland) was fought primarily as a guerrilla war,

with small-scale assaults against individual Russ-

ian units rather than large pitched battles (which

the Poles lacked the forces to win). Over the next

one and one-half years, 200,000 Poles took part in

POLICE

1198

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the fighting, with about 30,000 in the field at any

one moment.

After the revolt was crushed, thousands of

Poles were sent to Siberia, hundreds were executed,

and towns and villages throughout Poland were

devastated by the violence. All traces of Polish au-

tonomy were lost, and the most oppressive period

of Russification began.

See also: POLAND

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Leslie, R. F. (1963). Reform and Insurrection in Russian

Poland, 1856–1865. London: University of London,

Athlone Press.

Wandycz, Piotr. (1974). The Lands of Partitioned Poland,

1795–1918. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

B

RIAN

P

ORTER

POLITBURO

The Politburo, or Political Bureau, was the most

important decision-making and leadership organ in

the Communist Party, and has commonly been

seen as equivalent to the cabinet in Western polit-

ical systems. For most of the life of the Soviet sys-

tem, the Politburo (called the Presidium between

1952 and 1966) was the major focus of elite po-

litical life and the arena within which all impor-

tant issues of policy were decided. It was the heart

of the political system.

The Politburo was formally established at the

Eighth Congress of the Party in March 1919 and

held its first session on April 16. Formed by the

Central Committee (CC), the Politburo was to make

decisions that could not await the next meeting of

the CC, but over time its smaller size and more fre-

quent meeting schedule meant that effective power

drained into it and away from the CC. There had

been smaller groupings of leaders before, but these

had never become formalized nor had they taken

an institutional form. The establishment of the

Politburo was part of the regularization of the lead-

ing levels of the Party that saw the simultaneous

creation of the Orgburo and Secretariat, with these

latter two bodies meant to ensure the implementa-

tion of the decisions of leading Party organs, in

practice mostly the Politburo.

From its formation until late 1930, the Polit-

buro was one arena within which the conflict be-

tween Josef Stalin and his supporters on the one

side and successive groups of oppositionists among

the Party leadership was fought out, but with the

removal of Mikhail Tomsky in 1930, the last open

oppositionist disappeared from the Politburo.

Henceforth the body remained largely controlled by

Stalin. Its lack of institutional integrity and power

is illustrated by the fact that various of its mem-

bers were arrested and executed during the terror

of the mid- to late 1930s. After World War II, the

Politburo ceased even to meet regularly, being ef-

fectively replaced by ad hoc groupings of leaders

that Stalin mobilized on particular issues and when

it suited him.

Following Stalin’s death in 1953, the leading

Party organs resumed a more regular existence, al-

though Nikita Khrushchev’s style was not one well

suited to the demands of collective leadership; he

often sought to bypass the Presidium. Under Leonid

Brezhnev, the Politburo became more regularized,

and the overwhelming majority of national issues

seem to have been discussed in that body, although

an important exception was the decision to send

troops into Afghanistan in 1979. For much of the

Mikhail Gorbachev period, too, the Politburo was

at the heart of Soviet national decision making, al-

though the shift of the Soviet system to a presi-

dential one and the restructuring of the Politburo

at the Twenty-Eighth Congress in 1990 effectively

sidelined this body as an important institution.

The Politburo was always a small body. The

first Politburo consisted of five full and three can-

didate (or nonvoting) members; at its largest, when

it was elected at the Nineteenth Congress in 1952

and was probably artificially large because Stalin

was planning a further purge of the leadership (it

was also envisaged that there would be a small, in-

ner body), it comprised twenty-five full and eleven

candidate members. Generally in the post-Stalin pe-

riod it had between ten and fifteen full and five to

nine candidates. Membership has tended to include

a number of CC secretaries, leading representatives

from state institutions (although the foreign and

defense ministers did not become automatic mem-

bers until 1973) and sometimes one or two re-

publican party leaders. Gorbachev changed this

pattern completely in 1990 by making all republi-

can party leaders members of the Politburo along

with the general secretary and his deputy, and

eliminating candidate membership. It was over-

whelmingly a male institution, with only two

women (Ekaterina Furtseva and Alexandra Bir-

iukova) gaining membership, and it was always

dominated by ethnic Slavs, especially Russians.

POLITBURO

1199

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

While the frequency of Politburo meetings is

somewhat uncertain for much of its life, it seems

to have met on average about once per week in the

Brezhnev period and after, with provision for a fur-

ther meeting if required. Meetings were attended

by all members plus a range of other people who

might be called in to address specific items on the

agenda. In addition, some issues were handled by

circulation among the members, thereby not re-

quiring explicit discussion at a meeting. No public

differences of opinion between Politburo members

were aired before the breakdown of many of the

rules of Party life under Gorbachev, and public una-

nimity prevailed. It is not clear that votes were ac-

tually taken; issues seem to have been resolved

through discussion and consensus. Whatever the

process, the Politburo was the central leadership site

of the Party and the Soviet system as a whole.

See also: BREZHNEV, LEONID ILICH; CENTRAL COMMITTEE;

COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE SOVIET UNION; GOR-

BACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH; PRESIDIUM OF

SUPREME SOVIET; STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Laird, Roy D. (1986). The Politburo: Demographic Trends,

Gorbachev and the Future. Boulder, CO: Westview

Press.

Lowenhardt, John; Ozinga, James R.; and van Ree, Erik.

(1992). The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Politburo. Lon-

don: UCL Press.

G

RAEME

G

ILL

POLITICAL PARTY SYSTEM

Following years of one-party politics in the Soviet

Union, post-communist Russia experienced a burst

of party development during the 1990s. Still, Rus-

sia’s party system remains underdeveloped. Al-

though political parties run candidates in national

parliamentary elections, Russia’s first two presi-

dents, Boris Yeltsin and Vladimir Putin, chose not

to affiliate themselves with political parties. Rus-

sia’s constitution gives the president the power to

form the government without reference to the bal-

ance of party strength in the parliament. Politicians

in the State Duma usually affiliate themselves with

parties or party-like factions, but almost no par-

ties have well-developed organizational bases among

the electorate. Most voters have only dim concep-

tions of the policy positions of the major political

parties. New parties constantly form and dissolve.

The function often ascribed to political parties

in developed democracies—that of linking voters’

interests with the policy decisions of government—

is scarcely visible in Russia. Nonetheless, a rudi-

mentary party system was in place by the late

1990s.

Russia’s parties may be characterized as fall-

ing into five major types. On the left are Marxist-

Leninist parties. The most prominent example is the

Communist Party of the Russian Federation, headed

by Gennady Zyuganov. The CPRF is characterized

by a militantly anti-capitalist stance, which it com-

bines with appeals to Russian statist, nationalist,

and religious traditions. It is the strongest political

party in Russia both in its membership and in the

number of votes it attracts in elections (it can count

on the support of about 20 to 25 percent of the

electorate). It also enjoys a distinct ideological iden-

tity in voters’ minds. Despite its large following,

however, it has been unable to exercise much in-

fluence in policy making at the national level. Other

parties on the left are still more radical in their ide-

ologies and call for a return to Soviet-era political

and economic institutions; some expressly advocate

a return to Stalinism.

A second group of parties can be called “social

democratic.” They accept the principle of private

ownership of property. At the same time, they call

for a more interventionist social policy by the gov-

ernment to protect social groups made vulnerable

by the transition from communism. The party

headed by Grigory Yavlinsky, called Yabloko, is an

example. Yabloko attracts 7 to 10 percent of the

vote in national elections. Other parties that iden-

tify themselves as social democratic—including

a party organized by former president Mikhail

Gorbachev—have fared poorly in elections.

A third group of parties strongly advocate

market-oriented policies. They press for further

privatization of state assets, including land and in-

dustrial enterprises. They also seek closer integra-

tion of Russia with the West and the spread of

values such as respect for individual civil, political,

and economic liberties. The most prominent exam-

ple of such a party is the Union of Rightist Forces,

which drew around 8 percent of the vote in the

2000 parliamentary election.

A fourth group of parties appeal to voters on

nationalist grounds. Some call for giving ethnic

Russians priority treatment in Russia over ethnic

minorities. Others demand the restoration of a

POLITICAL PARTY SYSTEM

1200

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Russian empire. They denounce Western influences

such as individualism, materialism, and competi-

tiveness. Some believe that Russia’s destiny lies

with a Eurasian identity that straddles East and

West; others take a more straightforwardly statist

bent and call for restoring Russian military might

and centralized state power. Nationalist groups are

numerous and skillful at attracting attention, but

tend to be small. However, Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s

Liberal Democratic Party of Russia gained some

successes in elections during the 1990s (22% in

1993, 12% in 1995).

The fifth group may be called “parties of

power.” These are parties that actively avoid tak-

ing explicit programmatic stances. They depend in-

stead on their access to state power and the

provision of patronage benefits to elite supporters.

Their public stance tends to be centrist, pragmatic,

and reassuring. The major party of power in the

2000 election was “Unity,” which benefited from

an arms-length association with Vladimir Putin.

The problem for parties of power is that they have

little to offer voters except their proximity to the

Kremlin; if their patrons reject them or lose power,

they quickly fade from view.

Many voters can identify a party that they pre-

fer over others, but Russian voters on the whole

mistrust parties and feel little sense of attachment

to them. Likewise most politicians, apart from

Communists, feel little loyalty or obligation to par-

ties. The conditions favoring the development of

a party system—a network of civic and social as-

sociations able to mobilize support behind one or

another party, and a political system in which

the government is based on a party majority in

parliament—remain weak in Russia. It is likely that

the development of a strong, competitive party sys-

tem will be a protracted process.

See also: COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERA-

TION; LIBERAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY; UNION OF RIGHT

FORCES; YABLOKO.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Colton, Timothy J. (2000). Transitional Citizens: Voters

and What Influences Them in the New Russia. Cam-

bridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Fish, M. Stephen. (1996). Democracy from Scratch: Oppo-

sition and Regime in the New Russian Revolution.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

McFaul, Michael. (2001). Russia’s Unfinished Revolution:

Political Change from Gorbachev to Putin. Ithaca, NY:

Cornell University Press.

White, Stephen; Rose, Richard; and McAllister, Ian.

(1996). How Russia Votes. Chatham, NJ: Chatham

House Publishers.

T

HOMAS

F. R

EMINGTON

POLL TAX See SOUL TAX.

POLOTSKY, SIMEON

(1629–1680), major religious and cultural figure

at the Russian court from 1664 until his death in

1680.

Simeon Polotsky, born Samuil Petrovsky-

Sitnianovich, was a Belorussian monk from Polotsk.

He introduced new forms of religious literature de-

rived from Western models, and created the first

substantial body of poetry in Russian.

Native to a largely Orthodox area of the Polish-

Lithuanian state during a period of intense Catholic-

Orthodox rivalry, Samuil Sitnyanovich entered the

Kiev Academy around 1650, where he received a

typical Western education from Ukrainian Ortho-

dox teachers. He mastered Polish and Latin as well

as the neo-Aristotelian curriculum dominant in

Polish and Ukrainian schools. He continued his ed-

ucation at the Jesuit academy in Wilno. The Russo-

Polish War of 1653–1667 that followed on the

Ukrainian Cossack revolt of 1648 restored Ortho-

doxy to power in Polotsk, and Samuil returned

to his native town. In 1656 he became a monk

with the name Simeon in the local Bogoyavlenie

Monastery; he also became a teacher in a school

for Orthodox boys. During these early years he

wrote both verse and declamations in Polish and

Latin as well as Slavonic. On his first trip to

Moscow in 1660 with a delegation of Polotsk clergy

he presented Tsar Alexei Mikhaylovich with a se-

ries of verse greetings and other compositions for

court occasions. Long commonplace in Poland and

the West, such court poetry was unknown in Rus-

sia. With the revival of Polish military fortunes to-

ward the end of the war, Polotsk returned to

Catholic rule and Simeon left for Moscow in 1664,

never to return.

In Moscow Simeon played a major role in the

cultural and religious life of the court. After the

Church Council of 1666–1667, he prepared the of-

ficial reply to the claims of the Old Ritualists that

that liturgical reforms of Patriarch Nikon were

POLOTSKY, SIMEON

1201

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

heretical (Zhezl pravleniia/The Staff of Governance,

Moscow, 1668). In 1667 and 1670 he was tutor to

the heirs to the throne, Tsarevich Alexei (d. 1670)

and the future tsar, Fyodor (1672–1682), and also

kept a school in the Zaikonospassky Monastery on

Red Square. Simeon continued to write occasional

verse for the court and church, celebrating impor-

tant events and people. Many of these poems seem

to have been declaimed in public, though they re-

mained unpublished at his death. He was also a pro-

lific writer of sermons, two large volumes of which

appeared after his death, one of sermons at church

festivals (Obed dushevny/The Soul’s Dinner, Moscow

1681) and the other of sermons for particular

occasions, such as funerals of prominent boyars

(Vecheria dushevnaya/The Soul’s Supper, Moscow,

1683). The sermons, delivered in churches in and

around the Kremlin to the Russian elite, encouraged

a shift in religious experience away from the cen-

tral preoccupation with liturgy toward the inner

experience of Christianity and its moral teachings.

Simeon’s work introduced new genres to liter-

ature, poetry to court life, and a new style to Or-

thodox spirituality in Russia. His most important

pupil was Silvester Medvedev (1641–1691), and he

was popular both at court and in the church. Pa-

triarch Ioakim (1674–1690), however, was less

favorable, apparently distrusting the religious im-

plications of his Western orientation. Simeon was

a major influence for a generation after his death,

but his baroque forms and Slavonic style soon ren-

dered him too old-fashioned for later Russian poets

and preachers. Nineteenth-century literary scholars,

who looked askance at baroque style and genres

such as court poetry, paid little attention to Simeon.

Twentieth-century appreciation of the Baroque al-

lowed him recognition as a major cultural figure,

and the broader publications of his poetry have

given him a greater audience. Historians of religion

have recognized his pivotal role in the reorientation

of Orthodoxy in the years preceding the great cul-

tural changes of the time of Peter the Great.

See also: ORTHODOXY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bushkovitch, Paul. (1992). Religion and Society in Russia:

The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Vroon, Ronald. (1995). “Simeon Polotsky.” In Early Mod-

ern Russian Writers: Late Seventeenth and Eighteenth

Centuries, ed. Marcus C. Levitt (Dictionary of Literary

Biography, vol. 150). Detroit: Gale Research.

P

AUL

A. B

USHKOVITCH

POLOVTSY

Polovtsy, a nomadic Turkic-speaking tribal con-

federation (Polovtsy in Rus sources, Cumans in

Western, Kipchaks in Eastern) began migrating in

about 1017 or 1018 from eastern Mongolia and

occupied the area stretching from Kazakhstan to

the Danube by 1055. Politically disorganized and

lacking a unified policy in their relations with Rus,

various Polovtsian tribes became involved in Rus

inter-princely conflicts and, at times, fought as Rus

allies against other Polovtsy. Dynastic intermar-

riages often solidified Polovtsy-Rus political unions.

Rus sources note two distinct Polovtsy: “Wild” (Rus

enemies) and “Non-Wild” (Rus allies). Most Rus-

Polovtsy confrontations resulted from their differ-

ing economies. As agriculturalists, the Rus desired

to convert the steppe into cultivated lands, while

the nomadic Polovtsy required the steppe for graz-

ing animals. Consequently, conflict was inevitable:

Rus sources often speak of Polovtsian raids on lands

settled by Rus and subsequent Rus counterattacks.

However, because of the political disunity of both

sides, no permanent peace was ever reached, and

by the 1230s and 1240s, both were conquered and

absorbed into the Mongol Empire.

Polovtsy had settlements, probably occupied by

impoverished Polovtsy and Rus migrants who

practiced agriculture. Located between Rus and the

Black Sea, Polovtsy controlled trade between the

two regions and directly participated in commer-

cial activities. For their livestock, they received agri-

cultural products and luxury items from Rus.

Controlling much of the Crimea (particularly Su-

dak), the Polovtsy engaged in the sale of slaves and

furs to Byzantium and the Islamic East. While some

Polovtsy may have converted to Christianity and

Islam, the overwhelming majority retained their

shamanist-Täri religion.

See also: CRIMEA; KAZAKHSTAN AND KAZAKHS; KHAZARS;

KIEVAN RUS; POLYANE; VIKINGS.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Golden, Peter B. (1990). “The Peoples of the South Russ-

ian Steppe.” In The Cambridge History of Early Inner

Asia, ed. Denis Sinor. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Golden, Peter B. (1991). “Aspects of the Nomadic Factor

in the Economic Development of Kievan Rus’.” In

Ukrainian Economic History: Interpretive Essays, ed.

I.S. Koropeckyj. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Ukrainian

Research Institute.

POLOVTSY

1202

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY