Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

with Rachmaninov at the piano in the Moscow

Conservatory auditorium in 1892. A few years

later he composed his famous Piano Concerto No. 2

in C Minor. Soon after these successes he was ap-

pointed conductor at the Bolshoi Theater. Among

his other works were an opera (Aleko, 1892), The

Bells (a dramatic choral symphony composed in

1910), three instrumental symphonies, three other

piano concertos, the Vocalise (two versions, 1916 and

1919) and other songs, the Rhapsody on a Theme by

Paganini (1934), and the Symphonic Dances (1940).

With the coming of the Bolshevik seizure of

power in Russia in 1917, Rachmaninov exiled him-

self first to Germany, then to the United States. In

the United States he had conducted his first (in

1909) but by no means only concert tour. His sev-

eral succeeding appearances in New York City’s

Carnegie Hall won him early fame. Critics re-

marked at the unusual span of his hands as his fin-

gers raced through the rich chords and arpeggios.

After his departure from Russia, Rachmani-

nov’s writing remained outstanding. Found in the

repertoires of orchestras worldwide, the Symphony

No. 3 in A Minor (1936) is a stunning work whose

structure is studied in music school composition

classes. Some of Rachmaninov’s music was in-

cluded in film scores. Among these was the eerie

music of “Isle of the Dead” in a 1945 film with

Boris Karloff. Various parts of his other works turn

up in many films.

Rachmaninov’s music is considered Romantic

while bearing traces of typically Russian themes

and style of composition. Although banned in So-

viet Russia for more than seventy years, Rach-

maninov’s music is as much admired in his

homeland as the music of Tchaikovsky, Mus-

sorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, or Stravinsky. Begin-

ning just before the demise of Communist rule in

the early 1980s, Rachmaninov’s music again

adorned the repertoires of Russian orchestras.

See also: BOLSHOI THEATER; MIGHTY HANDFUL; MUSIC

A

LBERT

L. W

EEKS

RADEK, KARL BERNARDOVICH

(1885–1939), revolutionary internationalist and

publicist.

Born Karl Sobelsohn to Jewish parents in Lvov,

Karl Radek dedicated his life to international revo-

lution and political writing. He was active in so-

cialist circles from age sixteen and in 1904 joined

the Social Democratic Party of the Kingdom of

Poland and Lithuania. Before World War I, Radek

moved comfortably among Europe’s Marxist revo-

lutionaries. He became a member of the German So-

cial Democratic Party’s left wing in 1908, and wrote

on party tactics and international affairs for the

party’s press.

Radek opposed World War I and was active in

the Zimmerwald movement, an international so-

cialist antiwar movement organized in 1915. He

joined the Bolsheviks after the 1917 Revolution and

was a delegate to the Brest-Litovsk peace talks, al-

though he opposed the treaty and supported the

Left Communist opposition. Nonetheless, in 1918,

he became the head of the Central European Sec-

tion of the Commissariat of Foreign Affairs and

helped to organize the founding congress of the

German Communist Party. In 1919, he was elected

to the Bolshevik Party’s Central Committee and be-

came the Comintern secretary. He was removed

from this post in 1920, but remained a member of

the Comintern’s executive committee and the Cen-

tral Committee, and was active in German com-

munist affairs until 1924.

In 1924, Radek sided with Trotsky’s Left Op-

position and in consequence was removed from the

Central Committee. That same year he also opposed

changes in Comintern policy and thus was removed

from its executive committee. He was expelled from

the Party in 1927 and exiled. After recanting his

errors in 1929, he was readmitted to the Party and

became the director of the Central Committee’s in-

formation bureau and an adviser to Joseph Stalin

on foreign affairs. Radek helped to craft the 1936

Soviet constitution, but later that year he was ar-

rested and again expelled from the Party. At his

January 1937 Moscow show trial, he was con-

victed of being a Trotskyist agent and sentenced to

ten years in prison. He died in 1939.

Radek published routinely in the Soviet press

and authored several books on Comintern and in-

ternational affairs.

See also: CENTRAL COMMITTEE; COMMUNIST INFORMATION

BUREAU; COMMUNIST INTERNATIONAL; COMMUNIST

PARTY OF THE SOVIET UNION; LEFT OPPOSITION;

PURGES, THE GREAT; TROTSKY, LEON DAVIDOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lerner, Warren. (1970). Karl Radek: The Last Internation-

alist. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

RADEK, KARL BERNARDOVICH

1263

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Radek, Karl B., with Haupt, Georges (1974). “Karl Bern-

hardovich Radek.” In Makers of the Russian Revolu-

tion, ed. Georges Haupt and Jean-Jacques Marie, tr.

C.I.P. Ferdinand and D.M. Bellos. Ithaca, NY: Cor-

nell University Press.

W

ILLIAM

J. C

HASE

RADISHCHEV, ALEXANDER

NIKOLAYEVICH

(1749–1802), poet, thinker, and radical critic of

Russian society.

Alexander Nikolayevich Radishchev was ar-

rested for sedition by Catherine II in 1790 for the

publication of a fictional travelogue. Newly pro-

moted from assistant director to director of the St.

Petersburg Customs and Excise Department, he had

benefited from Catherine’s earlier enthusiasm for

the European Enlightenment. Following service as

a page at the Imperial Court from 1762 to 1767,

he had been selected as one of an elite group of stu-

dents sent to study law at Leipzig University, where

he had absorbed the progressive thinking of the

leading French philosophes. After completing his

studies in 1771 he returned to Russia, where he re-

sponded to Catherine’s encouragement for trans-

lating the works of the European thinkers of the

Enlightenment. His first literary venture, in 1773,

was a translation of Gabriel Bonnot de Mably’s Ob-

servations sur l’histoire de la Grèce, which idealized

republican Sparta. Radishchev’s first significant

original work, published in 1789, was his memoir,

Zhitie Fedora Vasilevicha Ushakova (The Life of Fedor

Vasilevich Ushakov), recalling idealistic conversa-

tions with a fellow student in Leipzig on oppres-

sion, injustice, and the possibilities for reform. This

was a prelude for Puteshestvie iz Peterburga v

Moskvu (A Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow), in

which an observant, sentimental traveler discovers

the various deficiencies in contemporary Russian

society.

At each staging post, an aspect of the state

of Russian society is revealed. For example, at

Tosna, the traveler observes feudalism; at Liubani,

it is forced peasant labor. Chudovo brings unchecked

bureaucratic power to his attention; he learns of

autocracy at Spasskaya Polest; and at Vydropusk

his attention is taken by the imperial court and

courtiers. Other stops along the road illuminate is-

sues such as religion, education, health, prostitu-

tion, poverty, and censorship in an encyclopedic

panorama of a sick society. No single cure is pro-

posed for Russia’s ills, but the underlying message

is that wrongs must be righted by whatever means

prove to be effective.

Deeply affected by the French Revolution of

1789, Catherine now read the work as an outra-

geous attempt to undermine her imperial author-

ity. An example was made of Radishchev in a show

trial that exacted a death sentence, later commuted

to Siberian exile. He was permitted to return to Eu-

ropean Russia in 1797, but he remained in exile un-

til 1801. Crushed by his experiences, he committed

suicide the following year. His Journey remained of-

ficially proscribed until 1905. Its author’s fate,

however, as much as the boldness of its criticism,

had won Radishchev the reputation of being the

precursor of the radical nineteenth-century intelli-

gensia.

See also: CATHERINE II; ENLIGHTENMENT, IMPACT OF; IN-

TELLIGENTSIA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Clardy, Jesse V. (1964). The Philosophical Ideas of Alexan-

der Radishchev. New York: Astra Books.

Lang, David M. (1959). The First Russian Radical: Alexan-

der Radishchev (1749–1802). London: Allen and Un-

win.

McConnell, Allen. (1964). A Russian Philosophe: Alexan-

der Radishchev 1749–1802. The Hague: Nijhoff.

W. G

ARETH

J

ONES

RADZINSKY, EDVARD STANISLAVICH

(b. 1936), playwright, author, popular historian,

and television personality.

A man of the 1960s, Edvard Radzinsky was

born in Moscow to the family of an intellectual.

He trained to be an archivist but began writing

plays during the late 1950s. During the 1960s and

the 1970s Radzinsky dominated the theatrical scene

in Moscow and gained international recognition.

His early plays explored the themes of love, com-

mitment, and estrangement (101 Pages About Love;

Monologue About a Marriage; “Does Love Really Ex-

ist?,” Asked the Firemen). In the final decades of stag-

nation under mature socialism, Radzinsky wrote a

cycle of historical–philosophical plays exploring the

RADISHCHEV, ALEXANDER NIKOLAYEVICH

1264

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

themes of personal responsibility, the struggle be-

tween ideas and power, and the roles of victim and

executioner (Conversations with Socrates; I, Lunin;

and Theater in the Time of Nero and Seneca). In the

same period he also wrote several grotesques that

drew their inspirations from great literary themes

and myths: The Seducer Kolobashkin (the Faust leg-

end) and Don Juan Continued (Don Juan in modern

Moscow).

Radzinsky refused to define his dramatic imag-

ination by the political events of 1917 and looked

to a larger intellectual world. With the collapse of

the Soviet Union, he shifted his creative efforts to

literature, writing Our Decameron on the decon-

struction of the Soviet intellectual life and history,

as well as writing unconventional biographies of

Nicholas II (The Last Tsar), Stalin, and Rasputin. In

each work Radzinsky enjoyed access to new

archival sources and wrote for a popular audience.

His works became international bestsellers. Some

historians criticized the special archival access he

obtained through his close ties with the govern-

ment of Boris Yeltsin. Others noted his invocation

of mystical and spiritual themes in his treatment

of the murder of the tsar and his family. Radzin-

sky has shown a profound interest in the impact

of personalities on history but is much opposed to

either a rationalizing historicism or an ideology-

derived historical inevitability. Radzinsky became a

media celebrity thanks to his programs on national

television about riddles of history. In 1995 he was

elected to the Academy of Russian Television and

was awarded state honors by President Yeltsin. Ap-

pointed to the Government Commission for the Fu-

neral of the Royal Family, Radzinsky worked

diligently to have the remains of Nicholas II and

his family buried in the cathedral at the Peter and

Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg.

See also: NICHOLAS II; RASPUTIN, GRIGORY YEFIMOVICH;

STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH; THEATER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kipp, Maia A. (1985). “The Dramaturgy of Edvard Radzin-

skii.” Ph.D. diss. University of Kansas, Lawrence.

Kipp, Maia A. (1985). “Monologue About Love: The Plays

of Edvard Radzinsky.” Soviet Union/Union Soviétique

12(3):305–329.

Kipp, Maia A. (1989). “In Search of a Synthesis: Reflections

on Two Interpretations of E. Radzinsky’s ‘Lunin, or,

the Death of Jacques, Recorded in the Presence of the

Master.’” Studies in Twentieth Century Literature

3(2):259–277.

Kipp, Maia A. (1993). “Edvard Radzinsky.” In Contempo-

rary World Writers ed. Tracy Chevalier. London: Saint

James Press.

Radzinsky, Edvard. (1992). The Last Tsar: The Life and

Death of Nicholas II. New York: Doubleday.

Radzinsky, Edvard. (1996). Stalin. New York: Double-

day.

Radzinsky, Edvard. (2000). The Rasputin File. New York:

Nan A. Telese.

J

ACOB

W. K

IPP

RAIKIN, ARKADY ISAAKOVICH

(1911–1987), stage entertainer, director, film actor.

Arkady Raikin ranks as one of the most pop-

ular and acclaimed stage entertainers of the Soviet

era. He was particularly well known for his un-

canny ability to alter his appearance through the

use of makeup, and his witty, satirical monologues

and one–man sketches endeared him to several gen-

erations of fans. As a young man Raikin worked

for a short time as a lab assistant in a chemical fac-

tory, but his real passion was acting. He enrolled

in the Leningrad Theater Institute, and upon his

graduation in 1935 he found employment with

the Leningrad Theater of Working-Class Youth

(TRAM). He also found his way into the movies,

and in 1938 he starred in The Fiery Years and Doc-

tor Kaliuzhnyi. He also appeared in films later in his

life and wrote and directed the 1974 television film

People and Mannequins.

But Raikin devoted the bulk of his creative en-

ergies to entertaining on the stage. In 1939 he

joined the prestigious Leningrad Theater of Stage

Entertainment and Short Plays (Leningradsky teatr

estrady i miniatyur), and in 1942 he became artis-

tic director of the theater. He remained affiliated

with this theater for the remainder of his career,

even after it moved to Moscow in 1982, where it

was renamed the State Theater of Short Plays.

Raikin also found success as master of ceremonies

for stage shows that allowed him to entertain au-

diences.

His many awards included People’s Artist of

the USSR (1968), Lenin Prize (1980), and Hero of

Socialist Labor (1981). In 1991 the Russian gov-

ernment honored him by issuing a postage stamp

in his name, and the Satyricon Theater (formerly

the State Theater of Short Plays) was named in

Raikin’s honor in 1991.

RAIKIN, ARKADY ISAAKOVICH

1265

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

See also: MOTION PICTURES; THEATER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beilin, Adolf Moiseevich. (1960). Arkadii Raikin. Leningrad:

Iskusstvo.

Uvarova, E. (1986). Arkadii Raikin. Moscow: Iskusstvo.

R

OBERT

W

EINBERG

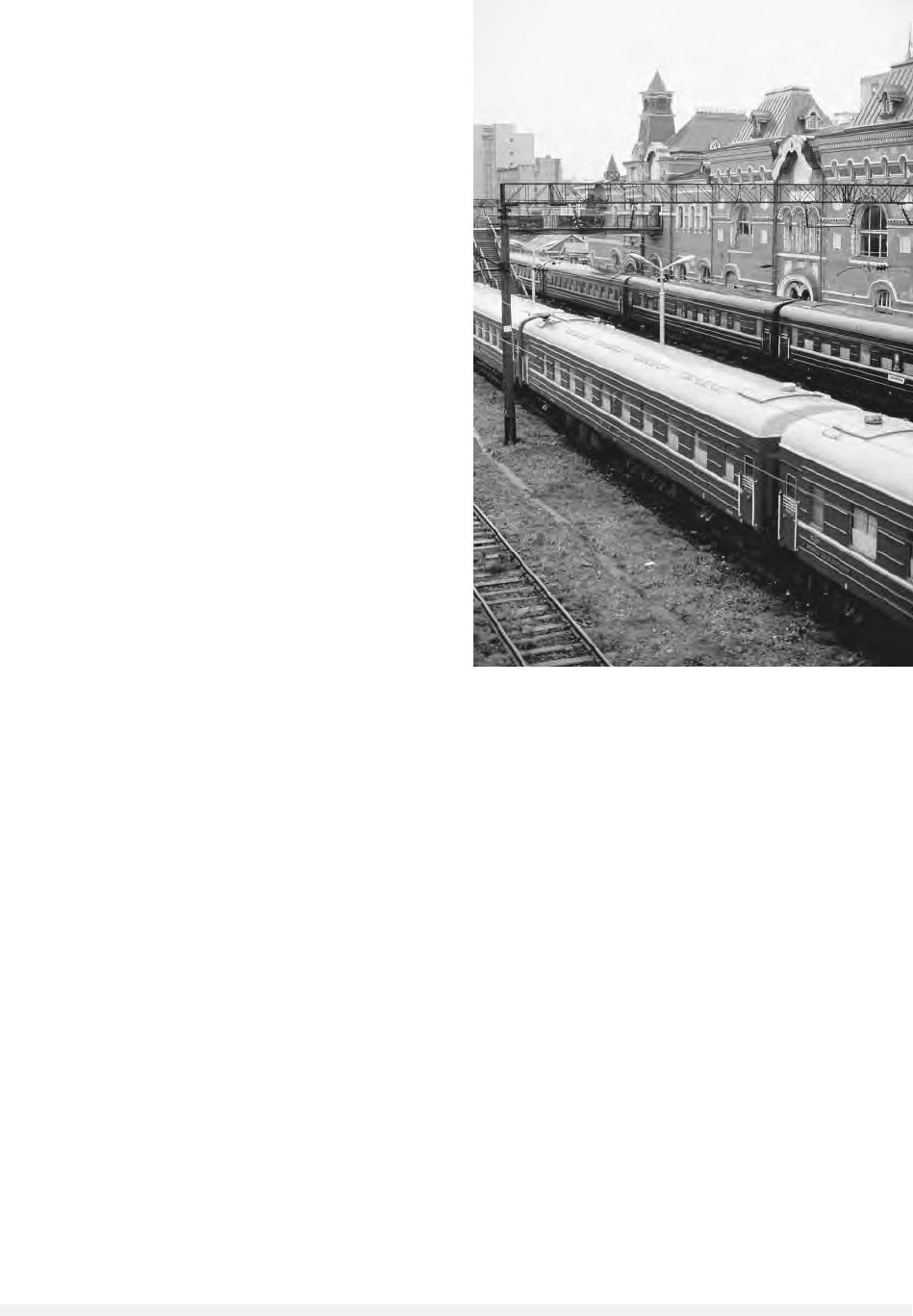

RAILWAYS

The first Russian railways, built as early as 1838,

were tsarist whimsies that ran from St. Petersburg

to the summer palaces of Tsarskoye Selo and

Pavlovsk. Emperor Nicholas I (r. 1825–1855) or-

dered the construction of these and the Moscow–St.

Petersburg line, which, according to legend, the tsar

designed by drawing a line on a map between the

two cities using a straight-edge and pencil. One

hundred fifty years later, the railway system had

expanded to almost 150,000 kilometers (90,000

miles), or almost two-thirds the length of the net-

work serving the United States. With 2.3 times the

territory of the United States, however, the net den-

sity of the Soviet Union’s rail system was only

about one-fourth as concentrated. It was, and is, a

system of trunk lines with very few branches,

which supplied only minimum service to major

sources of tonnage.

Naturally, this spartan system was severely

strained at any given time. Soviet freight turnover

was more than 2.5 times as great as that of the

United States, making it the most densely used rail

network in the world. At the time of the collapse

of the USSR, Soviet railways carried 55 percent

of the globe’s railway freight (in tons per kilome-

ter) and more than 25 percent of its railway

passenger-kilometers. Compared to other domestic

transportation alternatives, Soviet railways had no

comparison: They hauled 31 percent of the ton-

nage, accounted for 47 percent of the freight

turnover (in billions of ton-kilometers), and circu-

lated almost 40 percent of the inter-city passenger-

kilometers.

REGIONAL RAIL SYSTEMS

AND COMMODITIES

In the Russian Federation of the early twenty–first

century, the leading rail cargoes, ranked according

to tonnage, comprise coal, oil and oil products,

ferrous metals, timber, iron ore and manganese,

grain, fertilizers, cement, nonferrous metals and

sulfurous raw materials, coke, perishable foods,

and mixed animal feedstocks. The most conspicu-

ous Russian carrier is the Kemerovo Railway, which

hauls more than 200 million tons of freight per

year, two-thirds of which is coal from the mines

of the Kuznetsk Basin (Kuzbas), Russia’s greatest

coal producer. When the West Siberian and

Kuznetsk steel mills operate at full capacity, the

Kemerovo Line also carries iron and manganese,

iron and steel metals, fluxing agents, and coke.

Rounding out the freight structure are cement and

timber.

The only other railway that ships more than

200 million tons of freight is the Sverdlovsk, or

Yekaterinburg, Railway in the Central Urals. The

system’s most important cargoes include timber

from the nearby forests; ferrous metals from iron

and steel mills at Nizhniy Tagil, Serov, Chusovoy

and others; and petroleum products from the

refineries at Perm and Omsk. Other heavily used

railways comprise the October (St. Petersburg),

Moscow, North Caucasus, South Ural, and North-

ern lines, each shipping more than 140 million tons

per year. The much-heralded Baikal-Amur Main-

line (BAM) Railway, which became fully opera-

tional in December 1989, remains Russia’s most

lightly used network. Three-fifths of the freight it

transports is coal from the South Yakutian Basin.

REGIONAL BOTTLENECKS

In terms of combined freight and passenger

turnover (ton- and passenger-kilometers), the

world’s most heavily used segment of railroad

track stretches between Novokuznetsk in the

Kuzbas and Chelyabinsk in the southern Urals.

Parts of the Kemerovo, West Siberian, and South

Urals railways each maintain a share of this traf-

fic. While touring the Soviet Union in 1977, geo-

grapher Paul Lydolph observed train frequencies on

this segment as often as one every three minutes

in different locations and at various times during

the day. By the 1990s, operating at 95 percent

of its capacity, the West Siberian arm of the Trans-

Siberian Railway was critically overloaded. Ironi-

cally, 40 percent of the freight cars were usually

empty: Had these cars not been on the track, the

West Siberian line would have been running at

only 48 percent of capacity! Such was the waste

inherent in the Soviet centrally planned command

economy.

Since 1991, because of the alterations in the

freight-rate structure—the Soviet system was heav-

RAILWAYS

1266

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ily subsidized to keep the rates artificially low—

and the post-Soviet depressed economy through-

out Russia, particularly in coal mining, iron and

steel, and other bulk sectors, both the Kemerovo

and West Siberian railway networks have wit-

nessed sharp declines in usage. They continue to

represent bottlenecks, but these were much less se-

vere than the ones they became in the Soviet pe-

riod. The worst bottlenecks in the post-Soviet era

occur in ports—both river and sea—and at junc-

tions. The absolute worst are found in Siberia and

the Russian Far East, where traffic is heavy, there

are few lines, and management traditionally has

been lax.

POST–SOVIET PROBLEMS

Since 1991, railway headaches have been less as-

sociated with capacity and more with costs. In the

early 1990s, the Yeltsin government introduced

free–market principles and eliminated the artificial

constraints on prices and freight rates that had pre-

vailed in the USSR. The de-emphasis on the mili-

tary sector, which controlled at least one-fourth of

the Soviet economy, proved to be a devastating

blow to heavy industry and rail transport. The

multiplier effect diffused throughout the economy

of the Russian Federation, and soon fewer goods

and less output required circulation, and those

needing it had to be sent it at burdensome rates.

Spiraling inflation and underemployment brought

many industries to the edge of bankruptcy. Those

industries that survived often were deep in debt to

the railroads, which carried the output simply be-

cause they had nothing else to carry. Soon the rail-

roads, which were themselves in debt to their

energy suppliers, began to demand payment from

the indebted industries. This engendered a vicious

cycle wherein everyone was living on IOUs: in-

dustries owed the railways, which owed the energy

suppliers, who in turn owed the mining companies

that owed the miners, who could not buy the prod-

ucts of industry.

By 1991, the Soviet rail network was 35 to 40

percent electrified, and much of this electricity came

from coal-fired power plants. When the railways

could not pay their energy bill, coal miners did not

get paid. Since 1989, miners’ strikes over wages and

perquisites have often crippled the electrified rail-

ways. At times the miners have blocked the track

to protest their privations. Since the year 2000, this

vicious cycle has been alleviated because of high in-

ternational prices on petroleum and natural gas.

The resultant increase in foreign exchange income

has brought some relief to the Russian economy.

Wage arrears have been eliminated at least tem-

porarily, and the economy, including the Russian

railways, appears to have turned the corner.

See also: BAIKAL-AMUR MAGISTRAL RAILWAY; INDUSTRI-

ALIZATION; TRANS-SIBERIAN RAILWAY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ambler, John, et al. (1985). Soviet and East European

Transport Problems. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Hunter, Holland. (1957). Soviet Transportation Policy.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lydolph, Paul E. (1990). Geography of the USSR. Elkhart

Lake, WI: Misty Valley Publishing.

Mote, Victor L. (1994). An Industrial Atlas of the Soviet

Successor States. Houston, TX: Industrial Informa-

tion Resources, Inc.

RAILWAYS

1267

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Vladivostok is the eastern terminus of the Trans-Siberian

Railway. © W

OLFGANG

K

AEHLER

/CORBIS

Westwood, John N. (1964). A History of the Russian Rail-

ways. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

V

ICTOR

L. M

OTE

RAIONIROVANIE

Having inherited from the tsarist government a

large number of territorial divisions and subdivi-

sions, the Soviet leadership attempted to reduce

their numbers and simplify their bureaucracies.

Undertaken in the 1920s, this project to reorganize

the internal administrative map of Soviet Russia

was called raionirovanie, which can be translated

as regionalization. Soviet planners implemented

raionirovanie not only as a way of rationalizing

administrative structures, but as an essential tool

for the centralized planning of economic activity.

Before the reforms, Soviet central officials re-

garded the territorial divisions they inherited as

cumbersome and archaic obstacles to economic

growth. The basic divisions in tsarist administra-

tion were the province (guberniya), county (uezd),

rural district (volost), and village (selo). Their num-

ber expanded quickly in the first five years of the

new regime, fueling Bolshevik concerns about bu-

reaucratism—the perils of an expanding, unruly,

and unresponsive state administration. Specialists

in Gosplan (the State Planning Commission) desired

to reshape territorial administration to conform to

their vision of the economic needs of the country.

Its planners designed new territorial units that

sought to follow the contours of regional agricul-

tural and industrial economies, based on natural

resources, culture, and patterns of production.

As a result of raionirovanie, the country’s

provinces were replaced by regions (oblast or krai),

which were divided into departments (okrugs re-

placed the counties), which were themselves divided

into districts (raions, which replaced the old rural

counties.) In light of a scarcity of trained adminis-

trators, each of these new units was larger than

the old, and therefore had less contact with the pop-

ulation. The first areas subject to regionalization

were the Urals, the Northern Caucasus, and Siberia,

between 1924 and 1926. Raionirovanie continued

in other areas of the country throughout the

decade, and was largely complete by 1929. The

process of creating regional economic planning

agencies under the direct, centralized leadership of

Moscow became a part of the essential infrastruc-

ture of the Five-Year plans, first adopted in 1928.

Objections to regionalization were raised by the

Commissariat of Nationalities and local leaders in

the autonomous and national republics, especially

in Ukraine, on the grounds that the centrally de-

signed plans overlooked diversity in local culture

and tradition as they sought to rationalize and cen-

tralize administration while maximizing economic

growth. Indeed, regionalization sought to eliminate

much of what remained of the tsarist administra-

tion in the countryside and the provinces. Beyond

the reorganization of territorial subdivisions, names

of cities, towns, and capitals were changed, as were

traditional borders, and, so planners hoped, loyal-

ties to the old ways. Similar to Napoleonic-era bu-

reaucratic reforms in France, the ultimate aim was

not only to rationalize administration and econ-

omy, but to reshape popular mentalities in line

with conditions in a new, post-revolutionary era.

See also: LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND ADMINISTRATION;

NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carr, Edward Hallett. (1964). Socialism in One Country,

1924–1926. London: Macmillan.

J

AMES

H

EINZEN

RAPALLO, TREATY OF

The Treaty of Rapallo was signed by Germany and

the Russian Socialist Federated Soviet Republic on

April 16, 1922.

As part of a plan to encourage economic re-

covery after World War I, the Allies invited Ger-

many and Soviet Russia to a European conference

in Genoa, Italy, in April 1922. Lenin accepted the

invitation and designated Foreign Minister Georgy

Chicherin to lead the Soviet delegation. Accompa-

nied by Maxim Litvinov, Leonid Krasin, and oth-

ers, Chicherin stopped in Berlin on his way to Italy

and worked out a draft treaty. The German gov-

ernment, still hopeful for a favorable settlement at

Genoa, refused to formalize the treaty immediately.

In Genoa, the Allied delegations insisted that the So-

viet government recognize the debts of the prerev-

olutionary governments. The Soviets countered

with an offer to repay the debts and compensate

property owners if the Allies paid for the destruc-

tion caused by Allied intervention. While these

negotiations remained deadlocked, the German del-

egation worried that an Allied-Soviet treaty would

RAIONIROVANIE

1268

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

leave Germany further isolated. When the Soviet

delegation proposed a private meeting, the Germans

accepted, and the Russian-German treaty was

signed by Chicherin and German foreign minister

Walter Rathenau.

The two sides agreed to drop all wartime claims

against each other, to cooperate economically, and

to establish diplomatic relations. The Treaty of Ra-

pallo surprised the Western powers. Germany

ended its isolation with an apparent shift to an

Eastern policy, while Soviet Russia found a trading

partner and won normalization of relations with-

out resolving the debt issue. This special relation-

ship between Soviet Russia and Germany, including

some military cooperation, lasted for ten years.

See also: GERMANY, RELATIONS WITH; WORLD WAR I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

League of Nations Treaty Series, Vol. 19. (1923). London:

Harrison and Sons.

H

AROLD

J. G

OLDBERG

RAPP See RUSSIAN ASSOCIATION OF PROLETARIAN WRIT-

ERS.

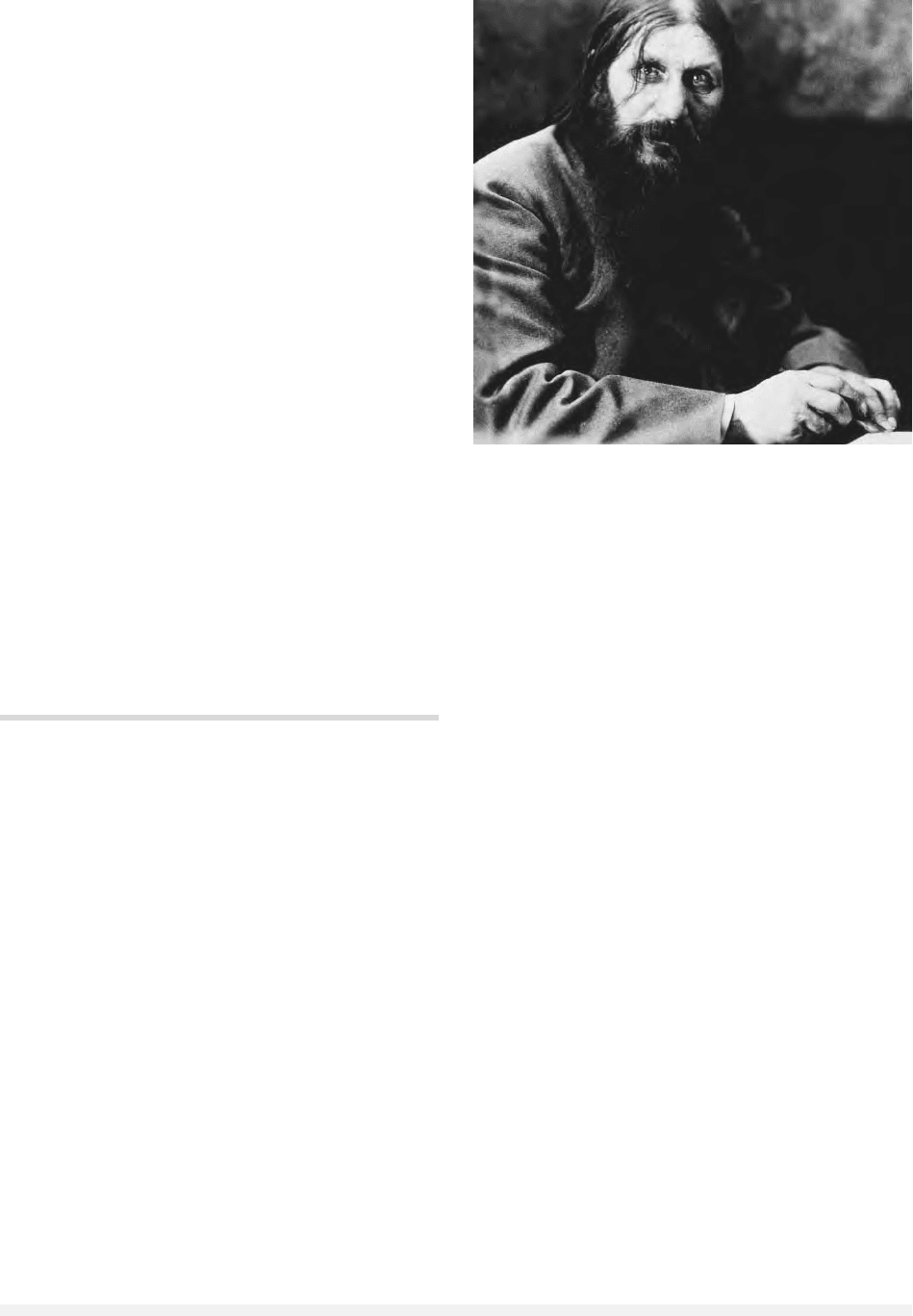

RASPUTIN, GRIGORY YEFIMOVICH

(1869–1916), mystic and holy man who befriended

Nicholas II and attained considerable power in late

Imperial Russia.

Born at Pokrovskoye, Siberia, January 10, 1869,

Rasputin was the son of Yefim, a prosperous, lit-

erate peasant. Young Grigory was alternately

moody and mystical, drunken and rakish. Marriage

did not settle him, but a pilgrimage to Verkhoture

Monastery, as punishment for vandalism (1885),

was decisive. The hermit Makary persuaded Grig-

ory to become a strannik (wanderer, religious pil-

grim). Rasputin also met the khlysty (flagellants,

Pentecostalists); though not a member (as often

charged), he embraced some of their ideas.

Rasputin’s captivating personality, his eyes,

and a memory for biblical passages made him a lo-

cal religious authority. Grigory never held a for-

mal position in the Church, but people recognized

him as a starets (elder, wise counselor). His spiri-

tual gifts apparently included healing. Although of

medium height and build, and not handsome,

Rasputin’s sensitive, discerning manner attracted

women and brought him followers and sexual con-

quests. His pilgrimages included Kiev, Jerusalem,

and Mt. Athos. Charges of being a khlyst forced

Rasputin to leave Pokrovskoye for Kazan in 1902.

By then, his common-law wife Praskovya had

borne him three children.

Rasputin impressed important clergy and lay-

people in Kazan, and they made possible his first trip

to St. Petersburg in 1903. He captivated church and

social leaders, and on a second visit, he met Nicholas

II. For a year, his friendship with the royal family

was based upon their interest in peasants with reli-

gious interests and messages. Rasputin first allevi-

ated the sufferings of their hemophiliac son Alexei

in late 1906. For the next ten years, Rasputin served

the tsarevich unfailingly in this capacity. Joseph

Fuhrmann’s biography reviews the theories offered

to explain this success, concluding that Rasputin ex-

ercised healing gifts through prayer. Robert Massie

explores hypnosis, rejecting the suggestion that hyp-

nosis alone could suddenly stop severe hemorrhages.

Rasputin exercised some influence over church-

state appointments before World War I. The high

point of his power came when Nicholas assumed

command at headquarters away from St. Peters-

burg, in August 1915. This elevated his wife’s im-

portance in government. Alexandra, in turn, relied

RASPUTIN, GRIGORY YEFIMOVICH

1269

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Grigory Rasputin, photographed in 1916. T

HE

A

RT

A

RCHIVE

/M

USÉE

DES

2 G

UERRES

M

ONDIALES

P

ARIS

/D

AGLI

O

RTI

upon Rasputin’s advice in appointments, though

neither controlled policies. As difficulties and de-

feats mounted, Russians became convinced that

Rasputin and Alexandra were German agents, and

that Nicholas was their puppet. Fearing this would

topple the dynasty, Felix Yusupov organized a con-

spiracy resulting in Rasputin’s murder in Petrograd

on December 17, 1916. Rasputin was poisoned, se-

verely beaten, and shot three times, and yet au-

topsy reports disclosed that he died by drowning

in the Neva River. Rasputin was buried at

Tsarskoye Selo until revolutionary soldiers dug up

the body to desecrate and burn it on March 9, 1917.

Rasputin favored Jews, prostitutes, homosex-

uals, and the poor and disadvantaged, including

and, in particular, members of religious sects. He

understood the danger of war, and did what he

could to preserve peace. But Rasputin was selfish

and shortsighted. He took bribes and was party to

corruption and profiteering during the war.

Rasputin ended as a womanizer and hopeless

drunk, who undermined the regime of Nicholas II

and hastened its collapse.

See also: ALEXANDRA FEDOROVNA; FEBRUARY REVOLU-

TION; NICHOLAS II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fuhrmann, Joseph T. (1990). Rasputin: A Life. New York:

Praeger.

King, Greg. (1995). The Man Who Killed Rasputin: Prince

Felix Youssoupov and the Murder That Helped Bring

Down the Russian Empire. Secaucus, NJ: Carol Pub-

lishing Group.

Massie, Robert K. (1967). Nicholas and Alexandra. New

York: Atheneum.

Radzinsky, Edvard. (2000). The Rasputin File. New York:

Nan A. Talese/Doubleday.

J

OSEPH

T. F

UHRMANN

RASTRELLI, BARTOLOMEO

(1700–1771), Italian architect who defined the high

baroque style in Russia under the reigns of Anne

and Elizabeth Petrovna.

Bartolomeo Francesco Rastrelli spent his youth

in France, where his father, the Florentine sculptor

and architect Carlo Bartolomeo Rastrelli, served at the

court of Louis XIV. After the death of the Sun King

in 1715, the elder Rastrelli left Paris with his son

and arrived the following year in St. Petersburg.

Recent research suggests that the young architect

did not return to Italy for study but remained in

Petersburg, where he worked on a number of

palaces during the years between the death of Pe-

ter (1725) and the accession of Anne (1730). Ras-

trelli’s rise in importance occurred during the reign

of Anne, who commissioned him to build a num-

ber of palaces in both Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Despite the treacherous court politics of the pe-

riod, Rastrelli not only remained in favor after the

death of Anne (1740), but gained still greater power

during the reign of Elizabeth Petrovna (1741–1761),

for whom he built some of the most lavish palaces

in Europe. Rastrelli’s major projects for Elizabeth

included a new Summer Palace (1741–1743; not

extant), the Stroganov Palace (1752–1754), the fi-

nal version of the Winter Palace (1754–1764), and

the Smolny Convent with its Resurrection Cathe-

dral (1748–1764). In addition, Rastrelli greatly en-

larged the existing imperial palaces at Peterhof

(1746–1752) and Tsarskoe Selo (1748–1756).

With the accession of Catherine II, who disliked

the baroque style, Rastrelli’s career suffered an ir-

reversible decline. He had received the Order of St.

Anne from Peter III and promotion to major gen-

eral at the beginning of 1762, but after the death

of Peter in July, Ivan Betskoi replaced Rastrelli as

director of imperial construction and granted him

extended leave to visit Italy with his family. Al-

though Rastrelli returned the following year, he

had in effect been given a polite dismissal with the

grant of a generous pension. He died in 1771 in St.

Petersburg.

See also: ANNA IVANOVNA; ARCHITECTURE; CATHERINE

II; ELIZABETH; WINTER PALACE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brumfield, William Craft. (1993). A History of Russian

Architecture. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Orloff, Alexander, and Shvidkovsky, Dmitri. (1996). St.

Petersburg: Architecture of the Tsars. New York:

Abbeville Press.

W

ILLIAM

C

RAFT

B

RUMFIELD

RATCHET EFFECT

The ratchet effect in the Soviet economy meant that

planners based current year enterprise output plan

RASTRELLI, BARTOLOMEO

1270

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

targets on last year’s plan overfulfillment. Fulfill-

ing output targets specified in the annual enterprise

plan, the techpromfinplan, was required for Soviet

enterprise managers to receive their bonus, a mon-

etary payment equaling from 40 to 60 percent of

their monthly salary. Typically, output plan tar-

gets were high relative to the resources allocated to

the enterprise, as well as to the productive capac-

ity of the firm. If managers directed the operations

of the enterprise so that the output targets were

overfulfilled in any given plan period (monthly or

quarterly), the bonus payment was even larger.

However, planners practiced a policy of “planning

from the achieved level,” the ratchet effect, so that

in subsequent annual plans, output targets would

be higher. Higher plan targets for output were not

matched by a corresponding increase in the alloca-

tion of materials to the firm. Consequently, over-

fulfilling output plan targets in one period reduced

the likelihood of fulfilling output targets and re-

ceiving the bonus in subsequent periods.

Planners estimated enterprise capacity as a di-

rect function of past performance plus an allowance

for productivity increases specified in the plan.

Knowing that output targets would be increased,

that is, knowing that the ratchet effect would take

effect, Soviet enterprise managers responded by

over-ordering inputs during the planning process

and by continually demanding additional invest-

ment resources to expand productive capacity. For

Soviet enterprises, cost conditions were not con-

strained by the need to cover expenses from sales

revenues. In other words, Soviet managers faced

a “soft budget constraint.” The primary risk asso-

ciated with excess demand for investment was the

increase in output targets when the investment pro-

ject was completed. However, the new capacity

could not be included as part of the firm until it

was officially certified by a state committee. By the

time this occurred, the manager typically had an-

other investment project underway.

In response to the ratchet effect, Soviet enter-

prise managers also tended to avoid overfulfilling

output targets even if it were possible to produce

more than the planned quantity. Several options

were pursued instead. Managers would save the

materials for future use in fulfilling output tar-

gets, or unofficially trade the materials for cash or

favors to other firms. Managers would produce

additional output, but not report it to planning

authorities, and then either hold or unofficially sell

the output. Due to persistent and pervasive short-

ages in the Soviet economy, and the uncertainty

associated with timely delivery of both the quan-

tity and quality of requisite material and techni-

cal supplies, the incentive to unofficially exchange

materials or goods between firms was very high,

and the risk of detection and punishment was very

low. Despite the comprehensive nature of the an-

nual enterprise plan, Soviet managers exhibited a

substantial degree of autonomy in fulfilling out-

put targets.

During perestroika, policy makers lengthened

the plan period to five years in order to eliminate

the pressures of the ratchet. However, in an envi-

ronment without a wholesale market, enterprise

managers were dependent upon their supplier en-

terprises to meet their plan obligations, and fulfill-

ing annual output plan targets remained the most

important determinant of the bonus payments. In

practice, lengthening the plan period did not elim-

inate the ratchet effect.

See also: ENTERPRISE, SOVIET; HARD BUDGET CONSTRAINTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Birman, Igor. (1978). “From the Achieved Level,” Soviet

Studies 31(2):153–172.

Gregory, Paul R. (1990). Restructuring the Soviet Economic

Bureaucracy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

S

USAN

J. L

INZ

RAZIN REBELLION

Of the four great rebellions that Russia experienced

between 1600 and 1800, the rebellion led by the

Don Cossack Stepan (Stenka) Razin has evoked the

most popular feeling. It did not involve the most

territory nor the widest diversity of population, but

it lasted the longest, and the name of Stenka Razin

has come to signify the very essence of Russian folk

spirit.

Stepan Razin’s life as a rebel began abruptly at

the age of thirty-seven, in April of 1667, when he

led a group of fellow Cossacks from their Don River

settlements to the Volga River for the purpose of

brigandage. The rebellion on the Lower Volga

started as a Cossack attack on a fleet of tsarist ships

sailing to Astrakhan. This success whetted the ap-

petite of the experienced frontier warriors for fur-

ther conquest. The state offered no resistance,

despite the brigands’ obvious intentions. In fact,

government troops at garrisons in Tsaritsyn,

RAZIN REBELLION

1271

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Chernyi Yar, and in Astrakhan occasionally joined

the rebels in looting and pillaging the rich com-

merce of the Lower Volga. In the spring of 1668,

after wintering at Yaitsk, Razin ventured into the

Caspian Sea, lured by the bountiful traffic of the

Shah of Persia. As many as one thousand Cossacks

took part in this campaign, which struck not only

at the shipping on the Caspian, but also attacked

commercial settlements and towns of the Cauca-

sus along the western shore, from Derbent south

to Baku. After wintering along the southern shore

in Persia, Razin’s band resumed the campaign in

1669 along the eastern shore among the settle-

ments of the Turkmen population of Central Asia.

They then decided to return to the Don in the fall

of 1669, with the riches and memories of their long

and exhilarating adventure that provided the ma-

terial for songs and legends that would be handed

down for generations.

In March of 1670, Razin announced to the Cos-

sack assembly (krug) that he intended to return to

the Volga, but instead of sailing against the Turks

or the Persians to the south, this time he pledged

to go “into Rus against the traitorous boyars and

advisers of the Tsar.” After once again securing

Tsaritsyn, Chernyi Yar, and Astrakhan by leaving

comrades in charge of these fortress towns at the

mouth of the Volga, Razin’s band moved quickly

up the river. In June and July, the townsfolk of

Saratov and Samara opened their gates to the Cos-

sacks, and the garrisons surrendered and joined the

rebel army. Razin again left Cossacks in charge to

supervise the looting and pillaging, while he set out

for the next fortified town, Simbirsk. (This town

was called Ulianovsk for six decades in the twen-

tieth century, commemorating it as the birthplace

of Lenin.)

Razin was forced to lay siege to Simbirsk. Af-

ter four unsuccessful assaults in September 1670,

and threatened by the approach of a major tsarist

force, Razin retreated down the Volga in early Oc-

tober. In the meantime, a massive uprising, in-

volving tens of thousands of Russians and native

non-Russians (Mordvinians, Chuvash, Cheremiss,

and Tatars) erupted in a forty thousand square

mile expanse of land called the Middle Volga re-

gion. For two months, local rebels controlled vir-

tually all of the territory within a rectangle bordered

roughly on four corners by the major towns of

Nizhny Novgorod, Kazan, Simbirsk, and Tambov.

The type of protest, the levels of violence, the char-

acter of leadership, and the extent of popular in-

teraction reflected the socioeconomic realities of the

vast region as they appeared on the eve of Razin’s

arrival. Local issues determined the pattern and en-

sured the stunning success of the Middle Volga re-

bellion in the first two months. At the same time,

these regional particulars eventually determined the

failure of the complex and uncoordinated insur-

gency in the ensuing two or three months. The up-

rising was finally crushed in January of 1671 by

the combined efforts of five Tsarist armies coordi-

nated by Prince Yuri Dolgorukov from a command

post in the midst of the region at Arzamas. In the

spring of 1671, a group of Cossacks betrayed the

location of Razin’s camp on the Don to the Cossack

chieftain (ataman), Kornilo Yakovlev. Yakovlev’s

forces captured Stenka Razin in May and brought

him in an iron cage to Moscow, where he was tried

and condemned for leading the rebellion, was anath-

ematized by the Russian Orthodox Church, and on

June 6 was hanged not far from Red Square and the

Kremlin just across the Moscow River.

Thus the state succeeded eventually in de-

stroying Stepan Razin and in imposing its will upon

the townsfolk, peasantry, the military, and the

rambunctious Russian and non-Russian Volga

frontier population. The rebellion solved nothing in

the long run, and very little in the short run.

Nonetheless, the name of Stenka Razin would live

forever as a reminder of this exciting time, and as

an enduring promise of relief to the oppressed. The

Razin Rebellion expresses a profound truth about

the meaning of Russia and its history. That truth

is exhilarating and romantic, but at the same time

it is violent, bloody, and hopelessly tragic.

See also: ALEXEI MIKHAILOVICH; COSSACKS; ENSERFMENT;

PEASANT UPRISINGS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Avrich, Paul. (1972). Russian Rebels: 1600–1800. New

York: Norton & Company.

Chapygin, Alexei Pavlovich. (1946). Stepan Razin, tr. Paul

Cedar. London: Hyperion Press.

Field, Cecil. (1947). The Great Cossack. London: Herbert

Jenkins.

Longworth, Philip. (1969). The Cossacks. New York: Holt,

Rinehart, and Winston.

Mousnier, Roland. (1970). Peasant Uprisings in Seven-

teenth-Century France, Russia, and China. New York:

Harper Torchbooks.

Ure, John. (2003). The Cossacks: An Illustrated History.

New York: Overlook Press.

J

AMES

G. H

ART

RAZIN REBELLION

1272

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY