Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

and subjecting not only clergy but also believers to

repression. To no avail: The January 1937 census

revealed that 55.3 percent of those over age 14 de-

clared themselves believers. That impelled the regime

to redouble its efforts. In 1937–1941, hundreds of

thousands were arrested and large numbers exe-

cuted.

Although World War II forced the Stalinist

regime to tolerate the reestablishment of many re-

ligious organizations, these encountered growing

pressure that continued past Stalin’s death in 1953.

The post-Stalinist regimes proved indefatigable in

efforts to efface the remnants of superstition. They

did achieve a reduction in organized religion: the

number of religious organizations in the USSR de-

clined by a third (from 22,698 in 1961 to 15,202

in 1985).

Even if religious organizations had dwindled,

the government proved far less effective in com-

bating religious observance. Indeed, data from the

latter period of Soviet rule showed clear signs of

religious revival. In the case of baptism, for exam-

ple, even if the aggregate figures between 1979 and

1984 decreased (by 6.7%), authorities could not fail

to notice increases in some non-Russian republics

(19.9% in Georgia, for example) and even in the

RSFSR (1.5%). Baptism rates, moreover, skyrocketed

among non-Orthodox Christians, with increases of

43.6 percent among Lutherans, 33.3 percent

among Methodists, and 52.1 percent among Men-

nonites. Data about monetary contributions—an

increase of 17.8 percent between 1979 and 1984—

gave the regime further cause for worry. These

funds allowed established religions to bolster their

central administrations (45.9% of funds), expand

support for clergy (14.3%), and spend more on re-

ligious artifacts and literature (17.4%).

Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika in the mid-

1980s brought a significant improvement in the

RELIGION

1283

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

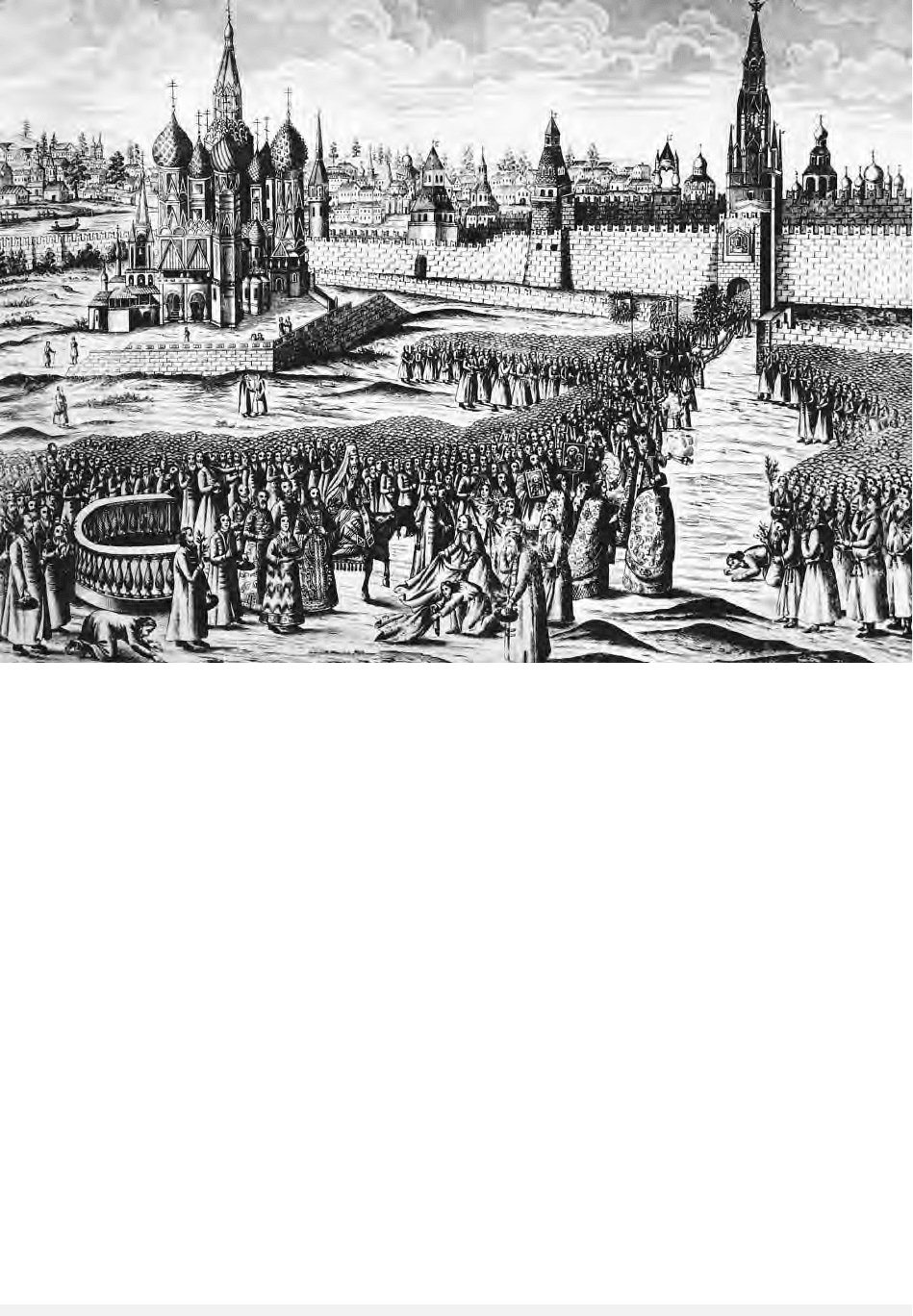

Procession of clergy outside Moscow’s city walls, 1867. © A

USTRIAN

A

RCHIVES

/CORBIS

status and activism of religion. That, doubtless,

was a key factor behind the stunning 36.6 percent

increase in religious groups in the Soviet Union

(from 12,438 in 1985 to 16,990 in 1990); in the

RSFSR, the rate of growth was only slightly

slower—32.6 percent (from 3,003 in 1985 to 3,983

in 1990). The expansion of organized religion

hardly abated after the fall of the Soviet Union in

1991: In the Russian Federation, the number of reg-

istered religious organizations rose fivefold (to

20,200 on December 31, 2000).

That growth has been somewhat troubling for

the Russian Orthodox Church. Although a major-

ity of the citizens in the Russian Federation profess

some vague allegiance to Orthodoxy, observants

are relatively few (4.5%), and still fewer attend ser-

vices on a regular basis. Still more alarming has

been the exponential growth of non-Orthodox re-

ligious groups, especially Christian evangelical and

Pentecostal movements. In an effort to contain cult

movements, the law on religious organizations

(October 1997) posed barriers to the registration of

new religious groups, that is, those that had

emerged within the last fifteen years, chiefly from

foreign missions. Nevertheless, by the closing dead-

line for registration on December 31, 2000, Rus-

sian Orthodoxy claimed only a slight majority

(10,913) of the 20,200 religious organizations in

the Russian Federation; the rest consisted of Mus-

lim (3,048), Evangelicals (1,323), Baptists (975),

Evangelical Christians (612), Seventh-Day Adven-

tists (563), Jehovah’s Witnesses (330), Old Believ-

ers (278), Catholics (258), Lutherans (213), Jews

(197), and various smaller groups.

See also: CATHOLICISM; HAGIOGRAPHY; ISLAM; JEWS;

MONASTICISM; ORTHODOXY; PAGANISM; PROTES-

TANTISM; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH; SAINTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, John. (1994). Religion, State, and Politics in the

Soviet Union and Successor States. New York: St. Mar-

tin’s Press.

Corley, Felix. (1996). Religion in the Soviet Union: An

Archival Reader. New York: New York University

Press.

Geraci, Robert P., and Khodarkovsky, Michael. (2001). Of

Religion and Empire: Missions, Conversion, and Toler-

ance in Tsarist Russia. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University

Press.

Hosking, Geoffrey A. (1991). Church, Nation, and State

in Russia and Ukraine. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Lewis, David C. (1999). After Atheism: Religion and Eth-

nicity in Russia and Central Asia. New York: St. Mar-

tin’s Press.

G

REGORY

L. F

REEZE

RENOVATIONISM See LIVING CHURCH MOVEMENT.

REPIN, ILYA YEFIMOVICH

(1844–1930), Russia’s most celebrated realist painter.

The future master of realism, whose genius

with the canvas put him on par with the literary

and musical luminaries of Russia’s nineteenth cen-

tury, Ilya Yefimovich Repin arose from truly in-

auspicious surroundings. His father, a peasant, was

a military colonist in the Ukrainian (then, “Little

Russia”) town of Chuguev. His talent manifested

itself early, and at age twenty, he entered St. Pe-

tersburg’s Academy of Arts. His first major piece,

The Raising of Jarius’s Daughter, won him the gold

medal in academic competition, and with it, a

scholarship to study in France and Italy. Although

the Impressionists at that time were beginning their

critical reappraisal of representation, Repin re-

mained a realist, although his use of light shows

that he did not escape the influence of the new style.

Upon his return to Russia, he developed a nation-

alist strain in his paintings that reflected the polit-

ical mood of his era. In this work, he connected the

realism of style with that of politics, bringing his

viewers’ attentions to the arduous circumstances

under which so many of their fellow citizens la-

bored, reflected in his first major work beyond the

Academy, Barge Haulers on the Volga.

Although Repin was never specifically a polit-

ical activist, he was nonetheless involved with other

artists in challenging the conservative, autocratic

status quo. For example, he joined with other

painters who, calling themselves the peredvizhniki,

or “itinerants,” revolted against the system of pa-

tronage in the arts and circulated their works

throughout the provinces, bringing art to the emer-

gent middle classes. Moreover, they chose compo-

sitions that depicted their surroundings, as opposed

to the staid classicism of mythology; Repin shifted

from Jarius’s Daughter to Russian legends, exem-

plified by several versions of Sadko, a popular fig-

ure from medieval, merchant Novgorod. More

impressive, though, were those among his works

that evoked the reality of all aspects of contempo-

RENOVATIONISM

1284

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

rary life, from the revolutionary movement to Rus-

sia’s colonial enterprise, from The Student-Nihilist to

The Zaporozhian Cossacks.

Repin also excelled as a portrait painter because

he was able to communicate the psychology of his

subjects. For example, his portrait of the tortured

Modest Mussorgsky stuns with its ability to bring

out varied aspects of the composer’s personality.

Repin’s oeuvre includes portraits of most promi-

nent liberals of his era, from Leo Tolstoy to Savva

Mamantov, as well as the archconservative Kon-

stantin Pobedonostsev. His paintings of historical

figures, Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan and

Tsarevna Sophia Alexeevna in the Novodevichy Con-

vent, likewise stand out for their capacity to evoke

the emotional.

Repin returned to the Academy of Arts in 1894,

directing a studio there until 1907 and serving

briefly as director (1898–1899). In 1900 he moved

to an estate in the Finnish village of Kuokalla, out-

side of St. Petersburg, where a constant stream of

visitors engendered a famously stimulating at-

mosphere. When Finland received its independence

from the Russian Empire in 1918, Repin chose to

remain there. The reacquisition of Kuokalla by the

Soviet army in 1939 resulted in the renaming of

the village to “Repino,” a museum to the artist.

See also: ACADEMY OF ARTS; NATIONALISM IN THE ARTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Parker, Fan and Parker, Stephen Jan. (1980). Russia on

Canvas: Ilya Repin. University Park: Pennsylvania

State University Press.

Sternin, Grigorii Iurevich, comp. (1987). Ilya Repin.

Leningrad: Aurora Publishers, 1987.

Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl. (1990). Ilya Repin and the

World of Russian Art. New York: Columbia Univer-

sity Press.

L

OUISE

M

C

R

EYNOLDS

REPRESSED INFLATION

The Soviet State Price Committee (Goskomtsen) set

prices for 27 million products during the post

World War II era. It compiled data on the unit la-

bor and capital cost of each good, and added a profit

mark up. The resulting prime cost–based prices

were supposed to be permanently fixed, but many

were revised every decade or so to reflect changes

in labor and non-labor input costs. These adjust-

ments should have been small, because the state

raised wages gradually, and improved technologies

reduced material input costs. Some sectors like ma-

chine building, where productivity growth was

especially rapid, even reported falling unit input

costs, creating a condition called “repressed defla-

tion” during the interval between the establishment

of the initial price and its revision. Had the Soviet

Union been a competitive market economy, char-

acterized by rapid technological progress and state

wage fixing, strong deflationary pressures would

have caused prices to fall continuously.

However, many prominent Soviet economists

such as Grigoriy Khanin contend that it was infla-

tion, not deflation that was repressed by the Soviet

brand of price fixing. They argue that while prices

were supposed to be fixed, enterprise managers

driven by a desire to maximize bonuses tied to prof-

its, circumvented the authorities, causing interme-

diate input prices and therefore unit costs to rise.

Had the Soviet Union been a competitive market

economy, strong cost-push inflationary pressures

would have forced prices to steadily rise.

Some Soviet economists, such as Igor Birman,

have claimed that repressed inflation was exacer-

bated by weak monetary discipline and soft bud-

getary constraints, which allowed firms to spend

more than they were authorized. The purchasing

power of these offending enterprises, and of the

public, therefore exceeded the cost of goods sup-

plied. This created inflationary excess demand that

was easily observed in empty shop shelves, rapidly

increasing savings deposits, and the public convic-

tion that money was worthless because there

weren’t enough things to buy.

The evidence for this position is inconclusive,

because goods were often distributed in worker

canteens instead of shops, and there could have

been many alternative reasons why bank savings

rose. Nonetheless, the consensus holds that the

USSR was, in some important sense, an economy

of shortage, in a state of monetary disequilibrium

that subverted effective planning and contributed

to the system’s undoing. Although repressed infla-

tion may have seemed innocuous because Soviet

growth between 1950 and 1989 was always pos-

itive, most specialists consider it to have been an

insidious source of destabilization.

Repressed inflation was specific to the Soviet

period, and has not carried over into the post-

communist epoch, because prices are no longer

REPRESSED INFLATION

1285

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

fixed or controlled. Price liberalization produced a

bout of hyper-inflation in 1992, only partly ex-

plained by the so-called Soviet “ruble overhang,”

but the problem subsequently subsided.

See also: ECONOMIC GROWTH, SOVIET; HARD BUDGET CON-

STRAINTS; MONETARY OVERHANG; RATCHET EFFECT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bornstein, Morris. (October 1978). “The Administration

of the Soviet Price System,” Soviet Studies 30(4):

466–490.

Grossman, Gregory. (1977). “Price Controls, Incentives

and Innovation in the Soviet Economy.” In The So-

cialist Price Mechanism, ed. Alan Abouchar. Durham,

NC: Duke University Press.

S

TEVEN

R

OSEFIELDE

REVOLUTION OF 1905

The immediate background to the first Russian rev-

olution, which, despite its designation as the “Rev-

olution of 1905,” actually began in 1904 and ended

in 1907, was the unexpected and humiliating de-

feat of Russia by the Japanese. The defeat embold-

ened the liberals, who in the fall and winter of

1904–1905 unleashed the so-called banquet cam-

paign for constitutional change. Meeting in twenty-

six cities, the liberals called for civil liberties,

amnesty for political prisoners, and a democrati-

cally elected constituent assembly. The banquets

were a prelude to the dramatic events of Bloody

Sunday (January 9, 1905), when government

troops fired on peaceful marchers (organized by Fa-

ther Gapon, founder of the Assembly of the Rus-

sian Factory and Mill Workers of the City of St.

Petersburg) who wished to present Tsar Nicholas II

(r. 1894–1917) with a petition for political and so-

cial reforms similar to those advocated by liberals

(significantly, without any demand for abolition of

the monarchy or introduction of socialism).

In light of the peaceful tactics and reformist

platform of the marchers, it is not surprising that

the massacre of 130 people and the wounding of

some three hundred provoked widespread outrage.

Within a few weeks, many industrial workers

throughout the empire went on strike to protest

the government’s conduct, assuming the role of a

viable political force for the first time. Students at

universities and high schools followed suit soon

afterward, disorders broke out among minorities

seeking cultural autonomy and political rights,

peasants attacked landlords’ estates, members of

the middle class defied governmental restrictions on

public meetings and the press, and on several oc-

casions soldiers and sailors mutinied. The entire

structure of society appeared on the verge of col-

lapse.

Incapable of coping with the growing unrest,

the government alternated between strident asser-

tions of the autocratic principle and vague promises

of reform, satisfying no one. The revolution peaked

in October, when a general strike, spontaneous and

unorganized, brought the government to its knees.

Once workers in Moscow walked off their jobs, the

strike spread quickly throughout the country, even

drawing support from various middle-class

groups. Numerous cities came to a standstill. Af-

ter about ten days, in mid-October, Tsar Nicholas,

fearing total collapse of his regime, reluctantly is-

sued the October Manifesto, which promised civil

liberties and the establishment of a legislature

(duma) with substantial powers. Most signifi-

cantly, the tsar agreed not to enact any law with-

out the approval of the legislature. In conceding

that he was no longer the sole repository of polit-

ical power, Nicholas did what he had vowed never

to do: He abandoned the principle of autocracy.

During the Days of Liberty, the period imme-

diately succeeding the issuance of the October Man-

ifesto, the press could publish whatever it pleased,

workers could form trade unions, and political par-

ties could operate freely. It was a great victory for

the opposition, but in a matter of days it became

evident that the revolutionary crisis had not been

overcome. The tsar made every effort to undo his

concessions. Large numbers of supporters of the

monarchy, enraged at the government’s conces-

sions, violently and indiscriminately attacked Jews

and anyone else deemed hostile to the old regime.

In the opposition, the St. Petersburg Soviet (coun-

cil of workers’ deputies) grew increasingly militant.

The upshot was that the Days of Liberty came to

an end within two months in a torrent of govern-

ment repression provoked by the uprising of

Moscow workers. Led by Bolsheviks and other rev-

olutionaries, this uprising was brutally quashed by

the authorities within ten days.

Nevertheless, the elections to the duma took

place. On the whole they proceeded fairly, with

some twenty to twenty-five million participant

voters. To the government’s surprise, the over-

REVOLUTION OF 1905

1286

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

whelming majority of the elected deputies belonged

to opposition parties. The newly formed Octobrist

Party, satisfied with the political changes intro-

duced by the October Manifesto, held only thirteen

seats; the extreme pro-tsarist right held none. On

the other hand, the Kadets, or Constitutional De-

mocrats, who favored a parliamentary system of

government, held 185 seats, more than any other

REVOLUTION OF 1905

1287

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Massacre at Tiflis Municipal Council, October 1905. T

HE

A

RT

A

RCHIVE

/D

OMENICA DEL

C

ORRIERE

/D

AGLI

O

RTI

(A)

party, and dominated the proceedings of the legis-

lature. Predictably, relations between the Duma and

the government quickly soured because of the leg-

islature’s demands for a constitutional order and

for agrarian measures involving compulsory dis-

tribution of privately owned land to land-hungry

peasants. On July 1906 the government dissolved

the Duma. The deputies protested the action at a

meeting in Vyborg, Finland, and called for passive

resistance, but to no avail. The Second Duma,

which met on February 20, 1907, and was more

radical than the first, met a similar fate on June 3

of that year. This marked the end of the Revolu-

tion of 1905. At this point the authorities changed

the electoral law by depriving many peasants and

minorities of the vote, ensuring the election of a

conservative Duma.

Never before had any European revolution been

spearheaded by four popular movements: the mid-

dle class, the industrial proletariat, the peasantry,

and national minorities (who demanded autonomy

or, in a few cases, independence). But because of

the disagreements and lack of coordination among

the various sectors of the opposition, and because

the government could still rely on the military and

on financial support from abroad, the tsarist

regime survived. Nevertheless, Russia had changed

significantly between 1904 and 1907. The very ex-

istence of an elected Duma, whose approval was

necessary for the enactment of most laws, dimin-

ished the power of the tsar and the bureaucracy.

The landed gentry, the business class, and the up-

per stratum of the peasantry, all of whom contin-

ued to participate in the elections of the Duma, now

exercised some influence in public affairs. More-

over, trade unions and various associations of co-

operatives that had been allowed to form during

the revolutionary turbulence remained active, and

censorship over the press and other publications

was much less stringent. In short, Russia had taken

a modest step away from autocracy and toward

the creation of a civil society.

See also: AUTOCRACY; BLOODY SUNDAY; BOLSHEVISM;

CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY; DUMA; LIBER-

ALISM; NICHOLAS II; OCTOBER GENERAL STRIKE OF 1905;

OCTOBER MANIFESTO; OCTOBRIST PARTY; WORKERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ascher, Abraham. (1988–92). The Revolution of 1905. 2

vols. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Bushnell, John S. (1985). Mutineers and Repression: Sol-

diers in the Revolution of 1905–1906. Bloomington:

Indiana University Press.

Emmons, Terence. (1983). The Formation of Political Par-

ties and the First National Elections in Russia. Cam-

bridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Engelstein, Laura. (1982). Moscow, 1905: Working-Class

Organization and Political Conflict. Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press.

Harcave, Sidney. (1964). First Blood: The Russian Revolu-

tion of 1905. New York: Macmillan.

Mehlinger, Howard D. and Thompson, John M. (1972).

Count Witte and the Tsarist Government in the 1905

Revolution. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Sablinsky, Walter. (1976). The Road to Bloody Sunday: Fa-

ther Gapon and the St. Petersburg Massacre of 1905.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Surh, Gerald D. (1989). 1905 in St. Petersburg: Labor, So-

ciety and Revolution. Stanford, CA: Stanford Univer-

sity Press.

Verner, Andrew M. (1990). The Crisis of Russian Autoc-

racy: Nicholas II and the 1905 Revolution. Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press.

A

BRAHAM

A

SCHER

REYKJAVIK SUMMIT

A summit meeting of U.S. president Ronald Reagan

and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev took place in

Reykjavik, Iceland, on October 11–12, 1986. This

second meeting of the two leaders was billed as an

“interim summit” and was not carefully prepared

and scripted in advance as was customary.

The Reykjavik summit unexpectedly became a

remarkable far-reaching exploration of possibilities

for drastic reduction or even elimination of nuclear

weapons. Gorbachev took the initiative, advancing

comprehensive proposals dealing with strategic of-

fensive and defensive weapons. Agreement seemed

at hand for reductions of at least 50 percent in

strategic offensive arms. When Reagan proposed a

subsequent elimination of all strategic ballistic

missiles, Gorbachev counterproposed eliminating

all strategic nuclear weapons. Reagan then said

he would be prepared to eliminate all nuclear

weapons—and Gorbachev promptly agreed.

This breathtaking prospect was stymied by dis-

agreement over the issue of strategic defenses. As

a condition of his agreement on strategic offensive

arms, Gorbachev asked that research on ballistic

missile defenses be limited to laboratory testing.

Reagan was adamant that nothing be done that

would prevent pursuit of his Strategic Defense Ini-

REYKJAVIK SUMMIT

1288

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

tiative (SDI). The meeting ended abruptly, with no

agreement reached.

Many saw the failure to reach accord as a spec-

tacular missed opportunity, while others were re-

lieved that what they saw as a near disaster had

been averted. Subsequent negotiations built on the

tentative areas of agreement explored at Reykjavik

and led to agreements eliminating all intermediate-

range missiles (the INF Treaty in 1987) and reduc-

ing intercontinental missiles (the START I Treaty in

1991). Thus, although the Reykjavik summit ended

in disarray, in retrospect the exchanges there con-

stituted a breakthrough in strategic arms control.

See also: ARMS CONTROL; STRATEGIC ARMS LIMITATION

TREATIES; STRATEGIC DEFENSE INITIATIVE; UNITED

STATES, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Garthoff, Raymond L. (1994). The Great Transition: Amer-

ican-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War.

Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Shultz, George P. (1993). Turmoil and Triumph: My Years

as Secretary of State. New York: Charles Scribner’s

Sons.

R

AYMOND

L. G

ARTHOFF

RIGA, TREATY OF (1921) See SOVIET-POLISH WAR.

RIGHT OPPOSITION

The Right Opposition, sometimes called Right De-

viation, represents a moderate strand of Bolshevism

that evolved from the New Economic Policy (NEP).

Headed by Nikolai Bukharin, the party’s leading

theoretician after Vladimir Ilich Lenin’s death, the

Right Opposition also included Alexei Rykov,

Mikhail Tomsky, Felix Dzerzhinsky, and A. P.

Smirnov. In part reacting against the harsh poli-

cies of War Communism, the right urged moder-

ation and cooperation with the peasantry to achieve

socialism gradually. It favored industrialization,

but at a pace determined by the peasantry, and pri-

oritized the development of light industry over

heavy industry.

Until early 1928 the platform of the right co-

incided with the policies of the Soviet government

and the Politburo. This is not surprising given that

Rykov was chairman of the Council of People’s

Commissars (Sovnarkom) from 1924 to 1930, and

Bukharin, Rykov, Tomsky, and their then ally

Josef Stalin held a majority in the Politburo until

1926. Participating in the struggles for power

following Lenin’s death, the right opposed Leon

Trotsky and his policies, as well as Grigory Zi-

noviev, Lev Kamenev, and eventually the United

Opposition. Toward the end of the 1920s, as Stalin

increasingly secured control over the party appa-

ratus, Trotsky, Zinoviev, and Kamenev were ex-

pelled from the Politburo and replaced by Stalin’s

handpicked successors, thereby enhancing the po-

sition of the right.

Their good fortune changed, however, follow-

ing the decisive defeat of the Left Opposition at the

Fifteenth Party Congress in December 1927. Hav-

ing supported Bukharin and the right’s position on

the cautious implementation of the NEP, Stalin, in

1928, abruptly reversed his position and adopted

the rapid industrialization program of the left. He

and his new majority in the Politburo then attacked

the Right Opposition over various issues including

forced grain requisitions, the anti–specialist cam-

paign, and industrial production targets for the

First Five–Year Plan. Outnumbered and unable to

launch a strong challenge against Stalin, the Right

Opposition sought an alliance with Kamenev and

Zinoviev, for which the Right Opposition was sub-

sequently denounced at the Central Committee

plenum in January 1929.

Under attack politically, Bukharin, Rykov, and

Tomsky signed a statement acknowledging their

“errors” that was published in Pravda in Novem-

ber 1929. Nonetheless, Bukharin was removed

from the Politburo that same month. The follow-

ing year Rykov and Tomsky were also expelled

from the Politburo. By the end of 1930 the trio was

removed from all positions of leadership, and mod-

erates throughout the party were purged; this of-

ficially marked the defeat of the Right Opposition.

Having already destroyed the Left Opposition,

Stalin was now the uncontested leader of the So-

viet Union.

The Great Purges of the late 1930s brought

further tragedy to the leaders of the defunct Right

Opposition. With his arrest imminent, Tomsky com-

mitted suicide in 1936. Two years later Bukharin

and Rykov were arrested and tried in the infamous

show trials of 1938. Despite the fact that they could

not possibly have committed the crimes that they

were accused of, and that their confessions were

clearly secured under torture, both were found

guilty and executed.

RIGHT OPPOSITION

1289

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

See also: BUKHARIN, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH; LEFT OPPOSI-

TION; RYKOV, ALEXEI IVANOVICH; TOMSKY, MIKHAIL

PAVLOVICH; UNITED OPPOSITION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cohen, Stephen, F. (1973). Bukharin and the Bolshevik Rev-

olution: A Political Biography, 1888–1938. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Erlich, Alexander. (1960). The Soviet Industrialization De-

bate, 1924–1928. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univer-

sity Press.

Merridale, Catherine. (1990). Moscow Politics and the Rise

of Stalin: The Communist Party in The Capital,

1925–32. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

K

ATE

T

RANSCHEL

RIMSKY-KORSAKOV, NIKOLAI

ANDREYEVICH

(1844–1908), prominent Russian composer who

contributed to the formation of a Russian national

music in the nineteenth century.

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov, a naval

officer by training, came to study professionally as

a member of Mily Balakirev’s amateur circle of

composers (“Mighty Handful”). An active composer

under Balakirev’s guidance since 1861, he became

a professor of composition and instrumentation

at the St. Petersburg conservatory ten years later.

Rimsky-Korsakov is regarded as one of the most

significant composers and musicians of Russia in

the nineteenth century.

Together with Balakirev and Alexander Bo-

rodin, who numbered among his closest creative

partners in the 1860s, Rimsky-Korsakov developed

a specific Russian idiom in orchestral music. As an

opera composer, although he wrote a few histori-

cal operas, Rimsky-Korsakov especially stands for

the Russian fairy and magic opera, the genre of

which he brought to a culmination. Of high though

not undisputed merit were the completions, revi-

sions, and instrumentations of opera torsos of

Borodin and Musorgsky, even if Rimsky-Korsakov

partly neglected the composers’ original intentions.

Finally, he made significant contributions to mu-

sical education. Not only did his textbook of har-

mony become the widely acknowledged standard

in Russia, but he also acted as a teacher and ex-

ample for outstanding Russian composers. His sup-

port of students in the Revolution of 1905 (leading

to his dismissal as professor) and his opera “The

Golden Cockerel” (1907), which was condemed by

censorship, because it could be interpreted as criti-

cism of tsarist rule, conributed to his renown and

reputation as an artist with political revolutionary

leanings. Furthermore, as one of the masters of

Russian national music in the nineteenth century,

he achieved enormous importance and influence in

the cultural history of the Soviet Union, particu-

larly since the cultural changes toward Great Russ-

ian patriotism under Stalin.

See also: MIGHTY HANDFUL; MUSIC; NATIONALISM IN THE

ARTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Seaman, Gerald R. (1988). Nikolai Andreevich Rimsky-

Korsakov: A Guide to Research. New York: Garland.

M

ATTHIAS

S

TADELMANN

RODZIANKO, MIKHAIL VLADIMIROVICH

(1859–1924), an anti-Bolshevik who led the con-

servative faction of the Octobrist Party in the pre-

revolutionary legislative Duma and served as

president of that body from 1911 to 1917, then

emigrated in 1920 to Yugoslavia, where he com-

pleted a memoir, The Reign of Rasputin.

Devoutly Orthodox, conservative, nationalist,

and loyal to the tsar, Mikhail Rodzianko also be-

lieved in the semiconstitutional system established

in 1906 and strove to make it work. He never

grasped that Nicholas II at heart rejected the new

order. The Duma leader was therefore always puz-

zled when the tsar ignored Rodzianko’s pleas to rid

the court of Rasputin’s pernicious influence and to

form a competent ministry.

An archetype of the old order, he came from a

prosperous landed family, received an elite educa-

tion, served in the army, and then became a dis-

trict marshal of nobility and zemstvo executive.

Chosen for the State Council in 1906 and elected to

the Third Duma in 1907, Rodzianko became Duma

president in 1911. He actively promoted the war

effort after 1914, and in 1916 warned the tsar that

incompetent ministers were undermining the

struggle against the Central Powers and endanger-

ing the survival of the monarchy itself.

During the Revolution of 1917, Rodzianko

urged the tsar to appoint a government in which

RIMSKY-KORSAKOV, NIKOLAI ANDREYEVICH

1290

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the people would have confidence and which he

hoped to head. As the revolution deepened he re-

luctantly agreed to help persuade Nicholas to ab-

dicate. Because of his political conservatism, he was

not asked, however, to serve in the new Provisional

Government.

As a believer in both the tsardom and consti-

tutionalism, he could only watch in dismay as Rus-

sia sank into radical revolution and civil war. In

emigration he found himself reviled by monarchists

as having betrayed the tsar, and rejected by liber-

als as having failed to be reformist enough.

See also: DUMA; NICHOLAS II; OCTOBRIST PARTY; REVO-

LUTION OF 1905

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi. (1981). The February Revolution,

Petrograd, 1917. Seattle: University of Washington

Press.

Hosking, Geoffrey. (1973). The Russian Constitutional Ex-

periment: Government and Duma, 1907-14. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Rodzianko, Mikhail V. (1973). The Reign of Rasputin: An

Empire’s Collapse. Gulf Breeze, FL: Academic Interna-

tional Press.

J

OHN

M. T

HOMPSON

ROERICH, NICHOLAS

KONSTANTINOVICH

(1874–1947), artist, explorer, and mystic.

Born in St. Petersburg and educated at the

Academy of Arts, Roerich established himself as a

painter of scenes from Slavic prehistory. Works

such as The Messenger (1897), Visitors from Overseas

(1901–1902), and Slavs on the Dnieper (1905) com-

bined a bold use of color with Roerich’s expertise

as a semi-professional archaeologist. Roerich joined

the World of Art Group and designed sets and cos-

tumes for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. His

greatest fame resulted from his designs for Prince

Igor (1909) and The Rite of Spring (1913), the li-

bretto of which he cowrote with Igor Stravinsky.

In 1918, Roerich and his family left Soviet Rus-

sia for Scandinavia, England, then the United

States. In New York, Roerich and his wife, Helena,

founded a spiritual movement: Agni Yoga, an off-

shoot of Theosophy. Roerich’s followers included

Henry Wallace, Franklin Roosevelt’s secretary of

agriculture (and later vice-president). His backers

built a museum for him in Manhattan and spon-

sored him on two expeditions to Asia. From 1920

onward, Roerich’s painting took on an Asiatic,

mystical character, featuring gods, gurus, and Hi-

malayan mountainscapes.

Roerich visited India in 1923. From 1925 to

1928, he and his family completed a mammoth

trek through Ladakh, Chinese Turkestan, the Altai

Mountains, the Gobi Desert, and Tibet. Ostensibly

leading an American archaeological, ethnographic,

and artistic expedition, the Roerichs also secretly

visited Moscow, and the true purpose of their jour-

ney remains a matter of debate. Roerich established

a research facility in the Himalayan village of Nag-

gar, India, and lobbied for the passage of an inter-

national treaty to protect art in times of war. This

effort gained him two nominations for the Nobel

Peace Prize. In 1934–1935, Roerich, bankrolled by

Wallace and the U.S. government, traveled to

Manchuria and Mongolia. The expedition stirred up

great scandal, leading Wallace and most of

Roerich’s supporters to break with him by 1936.

Roerich’s U.S. assets were seized. The Roerichs re-

mained in India, supporting the freedom movement

there and befriending its leaders, such as poet Ra-

bindranath Tagore and Jawaharlal Nehru. Roerich

died in 1947. Nehru, the new leader of independent

India, gave his eulogy.

Roerich’s occultism and the mysteries sur-

rounding his expeditions have shaped both popu-

lar and academic understanding of his life. Western

scholars acknowledge the importance of his early

art, but have criticized his later works; they have

tended to be suspicious about the political and

mystical motives underlying his expeditions. After

the late 1950s, Soviet scholars reinstated Roerich

as an important figure in the Russian artistic

canon, but downplayed his occultism and contro-

versial actions. Non-academic writing on Roerich

is either hagiographic—Agni Yoga has a worldwide

following, and the Russian movement has enjoyed

tremendous popularity since 1987—or lurid and

sensationalistic, accusing Roerich of espionage and

collaboration with the Soviet secret police. Since

the early 1990s, emerging evidence indicates that

the Roerichs believed a new age was imminent

and that one of its necessary preconditions was

the establishment of a pan-Buddhist state linking

Siberia, Mongolia, Central Asia, and Tibet. The

Roerichs also sought to involve themselves in the

struggle between Tibet’s key political figures, the

Panchen (Tashi) Lama and Dalai Lama. Rather than

ROERICH, NICHOLAS KONSTANTINOVICH

1291

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

straightforward espionage, the purpose of Roerich’s

expeditions seems to have been the fulfillment of

these grandiose, but ultimately quixotic, ambitions.

See also: BALLET; OCCULTISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Decter, Jacqueline. (1997). Messenger of Beauty: The Life

and Visionary Art of Nicholas Roerich. Rochester, VT:

Park Street Press.

McCannon, John. (2001). “Searching for Shambhala:

The Mystical Art and Epic Journeys of Nikolai

Roerich.” Russian Life 44(1):48–56.

Meyer, Karl, and Brysac, Shareen Blair. (1999). Tourna-

ment of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Em-

pire in Central Asia. Washington, DC: Counterpoint.

Williams, Robert C. (1980). Russian Art and American

Money: 1900–1940. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Uni-

versity Press.

J

OHN

M

C

C

ANNON

ROMANIA, RELATIONS WITH

Founded in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries,

the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia gained

their autonomy from the Hungarian kings with

the election of native princes. The status of these

principalities was comparable to that of the Grand

Duchy of Moscow, and they shared allegiance to

the patriarch of Constantinople. During the fif-

teenth century, the chief threat they faced was

Turkish expansionism in the Balkans. Their earli-

est contact with Moscow occurred when Ivan III

negotiated a marriage alliance with Steven the Great

of Moldavia (1457–1604). His daughter, Elena, be-

came the bride of Ivan the Young, whose son

Dmitry became heir to the throne.

THE LIBERATION OF ROMANIAN

LANDS FROM THE TURKS

As the power of the Romanian princes declined and

those of the grand dukes increased, the former tried

to switch their allegiance from Constantinople

to Moscow. Such contacts encouraged Nicholas

Milescu, a Moldavian boyar, to serve Tsar Alexei

as ambassador to China. The earliest attempt at

signing a treaty of alliance with Russia was made

by Prince Dmitry Cantemir of Moldavia, who in-

vited Peter the Great (r. 1682–1725) to deliver the

country from the Turks. The liberation failed with

Peter’s defeat on the River Pruth in 1711, but it

opened a career for Dmitry at St. Petersburg as a

Westernizer, and for his daughter, Maria, who ded-

icated herself to emancipating the Russian women.

The true liberator of Romanian lands was

Catherine the Great (r. 1762–1796) who, in three

campaigns against the Turks, reached the Dniester

River. The Treaty of Kutchuk Kainardji (1774) gave

Russia formal influence in the principalities, with

two consuls at Bucharest and Jassy. French inter-

ference with these provisions occasioned the Russo-

Turkish War of 1802–1812, which gave Russia the

Bessarabian half of Moldavia. Although the Greek

revolution of 1821 began in Moldavia, Tsar Alexan-

der I (r. 1801–1825) denounced it because of the

anti-revolutionary stance of the Holy Alliance (an

informal agreement among Christian monarchs to

preserve European peace). Russia’s greatest gain oc-

curred following the Treaty of Adrianopole, when

Tsar Nicholas I (r. 1825–1855) established a pro-

tectorate over both Romanian provinces, thus tak-

ing over the nominal Turkish suzerainty. Although

native Romanian princes continued to be elected,

power now resided with the two Russian procon-

suls who were headquartered in Bucharest and

Jassy.

Russia demanded that the new generations be

schooled at St. Petersburg, but Romanians preferred

the schools in Paris, where many of their young

people participated in the 1848 revolution against

the July monarchy. When they returned home and

attempted to continue that revolution in the Ro-

manian capitals, Russia suppressed the movement

and reoccupied the provinces under more stringent

conditions. The Congress of Paris, which followed

the Crimean War (1853–1856), suppressed the

Russian protectorate, internationalized Danubian

navigation, reunited Bessarabia with Romania, and

attempted to revise the constitution of both states.

The Romanians took the initiative of electing

Alexander Ion Cuza in 1859 as prince of the United

Principalities, as Moldavia and Wallachia were now

called, but this arrangement disturbed Austria and

Turkey more than it did Russia.

The overthrow of Cuza in a military coup, and

the advent of Prince Charles of Hohenzollern Sig-

maringen in 1866, was greeted positively by Aus-

tria after he visited Tsar Alexander II (r. 1855–1881)

at Livadia in 1869. The Bosnian crisis that led to the

Balkans war of independence (1877–1878) gave Rus-

sia the opportunity to avenge its defeat in 1856. Ini-

tially neutral during this war, Romania nonetheless

gave Russia a right of passage to Bulgaria, albeit with

misgivings. However, when Grand Duke Nicholas

ran into difficulties at Plevna, in Bulgaria, he ap-

ROMANIA, RELATIONS WITH

1292

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY