Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

musicians, to form circles, attend salons, and group

around enlightened patrons.

CROSSING BORDERS

In this kind of atmosphere, crossing of borders

between different arts was common. Vasily Zhukov-

sky produced brilliant drawings; Lermontov nearly

abandoned writing for the sake of painting; Vladimir

Odoyevsky was a musicologist as well as a poet

and novelist; the playwright Alexander Griboye-

dov, a talented composer. As art historian Valery

Turchin points out, it was the musician rather than

the poet who was eventually promoted, in the view

of the Romantics, to the role of the supreme type

of artistic genius. This precisely reflected the Ro-

mantics’ quest for the spiritual, for music, of all

the arts, was considered the least bound by mate-

riality. Arguably, Romanticism was a later phe-

nomenon in Russian music than in literature and

art. Anyway, a contemporary of Pushkin, the com-

poser Mikhail Glinka, renowned for his use of Russ-

ian folk tradition, was a major contributor to the

Romantic movement. The painter Orestes Kipren-

sky commenced his series of Romantic portraits

during the very dawn of literary Romanticism.

Somewhat later emerged the Romantic schools of

landscape and historical painting. Even in architec-

ture, the art most strongly bound by matter, new

trends showed up against the neoclassical back-

ground: neogothicism, exotic orientalism, and, fi-

nally, the national current exemplified in Konstantin

Ton’s churches. During the reign of Nicholas I

(1825–1855) Romanticism began to be diffused in

the more general quest for history and nationality.

SLAVOPHILISM

The important offshoot of this development was

Slavophilism. Nicholas I typified the new epoch in

the same way as Alexander I had typified the pre-

vious age. In his youth, Nicholas had received a

largely Romantic education. He was an admirer of

Walter Scott and was inclined to imitate the kings

of Scott’s novels. Characteristically, Pushkin, dur-

ing the reign of Nicholas, persistently returns to

the twin themes of nobility and ancestry, lament-

ing (in a manner closely resembling Edmund Burke)

the passing of the age of chivalry. The dominant

mood of the period, however, was nationalistic and

messianic, and here again the Romantics largely

shared the inclinations of the tsar. Notably, it was

Peter Vyazemsky who coined the word narodnost

(the Russian equivalent of “nationality”), which

became part of the official ideological formula (“Or-

thodoxy, Autocracy, Nationality”). Odoevsky ar-

gued that because of their “poetic organization,”

the Russian people would attain superiority over

the West even in scientific matters. Pushkin wel-

comed the suppression of the Polish uprising of

1831, interpreting it in Panslavic terms. Nonethe-

less, there was an unbridgeable psychological rift

between the tsar and the Romantic camp, which

had its origin in the catastrophe of December 1825.

Several of the Decembrists (most importantly, Kon-

draty Ryleyev, one of the five executed) were men

of letters and members of the Romantic movement.

Throughout the reign, a creative personality faced

fierce censorship and remained under the threat of

persecution. Many could say with Polevoy (whose

ambitious Romantic enterprise embraced, beside lit-

erature, history and even economics, but whose

Moscow Telegraph, Russia’s most successful literary

journal, was closed by the government): “My dreams

remained unfulfilled, my ideals, unexpressed.” The

split between ideal and reality was the central prob-

lem for Romanticism universally, but in Russia this

problem acquired a specifically bleak character.

See also: GOLDEN AGE OF RUSSIAN LITERATURE; LERMON-

TOV, MIKHAIL YURIEVICH; ODOYEVSKY, VLADIMIR FY-

ODOROVICH; PUSHKIN, ALEXANDER SERGEYEVICH;

SLAVOPHILES; ZHUKOVSKY; VASILY ANDREYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

McLaughlin, Sigrid (1972). “Russia: Romanic

eskij-

Romantic

eskij-Romantizm.” In “Romantic” and Its

Cognates: The European History of a Word, ed. Hans

Eichner. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Peer, Larry H. (1998). “Pushkin and Romantizm,” In

Comparative Romanticisms: Power, Gender, Subjectiv-

ity, ed. Larry H. Peer and Diane Long Hoeveler. Co-

lumbia, SC: Camden House.

Riasanovsky, Nicholas V. (1992). The Emergence of Ro-

manticism. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rydel, Christine, ed. (1984). The Ardis Anthology of Russ-

ian Romanticism. Ann Arbor, MI: Ardis.

Y

URI

T

ULUPENKO

ROSTISLAV

(d. 1167), grand prince of Kiev and the progenitor

of the Rostislavichi, the dynasty of Smolensk.

After Rostislav’s father Mstislav Vladimirovich

gave him Smolensk around 1125, he freed it from

ROSTISLAV

1303

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

its subordination to southern Pereyaslavl, fortified

it with new defensive walls, founded churches, and

patronized culture. Around 1150, despite opposi-

tion from Metropolitan Kliment (Klim) Smolyatich

and the bishop of Pereyaslavl, he also freed the

Church of Smolensk from its dependence on

Pereyaslavl by making it an autonomous eparchy.

Manuel, a Greek, was its first bishop, and the

Church of the Assumption, built by Rostislav’s

grandfather Vladimir Vsevolodovich “Mono-

makh,” became his cathedral. Rostislav also issued

a charter (gramota) enumerating the privileges of

the bishop and the church in Smolensk. The docu-

ment is valuable as a source of ecclesiastical, social,

commercial, and geographic information.

Rostislav had political dealings with neigh-

bouring Polotsk and Novgorod, but his most im-

portant involvement was in Kiev. After 1146 he

helped his elder brother Izyaslav win control of the

capital of Rus. Following the latter’s death in 1154,

the citizens invited Rostislav to rule Kiev with his

uncle Vyacheslav Vladimirovich, but his uncle

Yury Vladimirovich “Dolgoruky” replaced him in

the same year. Although Rostislav regained Kiev in

1159, his rule was not secured until 1161, when

his rival Izyaslav Davidovich of Chernigov died. As

prince of Kiev, he asserted his authority over the

so-called kernel of Rus and placated many of the

princes. He failed, however, to stop the incursions

of the Polovtsy. He died on March 14, 1167, and

was buried in Kiev.

See also: IZYASLAV MSTISLAVICH; KIEVAN RUS; VLADIMIR

MONOMAKH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dimnik, Martin. (1983). “Rostislav Mstislavich.” In The

Modern Encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet History, ed.

Joseph L. Wieczynski, 31:162–165. Gulf Breeze, FL:

Academic International Press.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

ROSTOVTSEV, MIKHAIL IVANOVICH

(1870–1952), Russian-American historian and arche-

ologist of Greek and Roman antiquity.

Mikhail Ivanovich Rostovtsev was born in Kiev

and educated at the Universities of Kiev and St. Pe-

tersburg. He taught at St. Petersburg University,

and in the Higher Women’s Courses until 1918,

rising to become a professor in 1912. His career be-

fore the revolution shows the international nature

of academic life: He published widely in English,

French, and German as well as Russian.

Rostovtsev refused to serve either in the Provi-

sional Government or in the Communist govern-

ment, and in emigration published extensive polemics

against the Communists. In 1918 Rostovstev fled

Russia, first to Oxford (1918–1920), and then to

the United States where he was professor first at

the University of Wisconsin (1920–1925) and then

Yale University (1925–1944).

Rostovtsev’s academic interests were extensive.

Trained as a philologist, he wrote monographs on

Roman tax farming and land tenure. As an art his-

torian he also published important works on the

art and history of south Russia that traced cultural

influences in Scythian art from Greece to the bor-

ders of China. From 1928 to 1936 he lead Yale’s

excavations at Dura-Europos in Syria.

His greatest fame, however, rests on two large

monographs: Economic and Social History of the Ro-

man Empire (Oxford, 1926) and The Social and Eco-

nomic History of the Hellenistic World (Oxford,

1941). In both these works he emphasizes the role

of the urban bourgeoisie in the development of the

two related cultures, and their decline due to state

intervention and outside attacks.

See also: EDUCATION; UNIVERSITIES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Momigliano, Arnaldo. (1966). Studies in Historiography.

London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Vernadsky, George. (1931). “M. I. Rostovtsev.” Seminar-

ium Kondakovianum 4:239–252.

A. D

ELANO

D

U

G

ARM

ROTA SYSTEM

Also known as the “ladder system,” the rota sys-

tem describes a collateral pattern of succession, ac-

cording to which princes of the Rurikid dynasty

ascended the throne of Kiev, the main seat of Kievan

Rus. The system prevailed from the mid-eleventh

century until the disintegration of Kievan Rus in the

thirteenth century. It also determined succession for

the main seats in secondary principalities within

Kievan Rus and survived in the northern Rus prin-

cipalities into the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

ROSTOVTSEV, MIKHAIL IVANOVICH

1304

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The design for the rota system has been at-

tributed to Prince Yaroslav the Wise (d. 1054), who

in his “Testament” or will divided his realm among

his sons. He left Kiev to his eldest son. He assigned

secondary towns, which became centers of princi-

palities that comprised Kievan Rus, to his younger

sons and admonished them to obey their eldest

brother as they had their father. Although the Tes-

tament did not provide a detailed order for succes-

sion, the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century

historians Sergei Soloviev and Vasily Klyuchevsky

concluded that it set up an arrangement for the en-

tire Rurikid dynasty to possess and rule the realm

of Kievan Rus. It created a hierarchy among the

princely brothers and, in later generations, cousins

that was paralleled by a hierarchy among their ter-

ritorial domains. It anticipated that when the prince

of Kiev died, he would be succeeded by the most

senior surviving member of his generation, who

would move from his seat to Kiev. The next prince

in the generational hierarchy would replace him,

with each younger prince moving up a step on the

ladder of succession. When all members of the el-

dest generation of the dynasty had died, succession

would pass to their sons. For a prince to become

eligible for the Kievan throne, however, his father

must have held that position.

The rota system was revised by a princely

agreement concluded at Lyubech in 1097. The agree-

ment ended the practice of rotation of the princes

through the secondary seats in conjunction with

succession to Kiev. Instead, a designated branch of

the dynasty would permanently rule each princi-

pality within Kievan Rus. The princes of each dy-

nastic branch continued to use the rota system to

determine succession to their primary seat. The ex-

ceptions were Kiev itself, where rotation among the

eligible members of the entire dynasty resumed af-

ter 1113, and Novgorod, which selected its own

prince after 1136.

Succession to the Kievan throne was, neverthe-

less, frequently contested. Scholars have interpreted

the repeated internecine conflicts and their meaning

for the existence and functionality of the rota sys-

tem in a variety of ways. Some regard the rota

system to have been intended to apply only to

Yaroslav’s three eldest sons and the three central

principalities assigned to them. Others have argued

that the system was not fully formulated by

Yaroslav, but evolved as the dynasty grew, took

possession of a greater expanse of territory, and had

to confront, by diplomacy and by war, unforeseen

complications in determining “seniority.” Others

contend that the Rurikid princes had no succession

system, but threatened or used force to determine

which prince would sit on the Kievan throne.

Despite the conflicts over succession, which

have been cited as an indicator of a weak political

system and a lack of unity within the ruling dy-

nasty, the rota system has also been interpreted as

a constructive means of accommodating compet-

ing interests and tensions among members of a

large dynasty. It enabled the dynasty to provide a

successor to the Kievan throne in an age when high

mortality rates tended to reduce the number of el-

igible princes. It also emphasized the symbolic cen-

trality of Kiev even as the increasing political and

economic strength of component principalities of

Kievan Rus undermined the unity of the dynastic

realm.

After the Mongol invasions of 1237 through

1240 and the disintegration of Kievan Rus, the rota

system continued to prevail in the northeastern Rus

principalities until Yuri (ruled 1317–1322) and

Ivan I Kalita (ruled 1328–1341) of Moscow, whose

father had not held the position, became grand

princes of Vladimir. Their descendants monopolized

the position and replaced the rota system with a

vertical succession system, according to which the

eldest surviving son of a reigning prince was heir

to the throne.

See also: KIEVAN RUS; YAROSLAV VLADIMIROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dimnik, Martin. (1987). “The ‘Testament’ of Iaroslav

‘The Wise’: A Re-examination.” Canadian Slavonic

Papers 29(4):369–386.

Kollmann, Nancy Shields. (1990). “Collateral Succession

in Kievan Rus’.” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 14(3/4):

377–387.

Stokes, A. D. (1970). “The System of Succession to the

Thrones of Russia, 1054–1113.” In Gorski Vijenac: A

Garland of Essays offered to Professor Elizabeth Mary

Hill, ed. R. Auty, L. R. Lewitter, A. P. Vlasto. Cam-

bridge, UK: The Modern Humanities Research Asso-

ciation.

J

ANET

M

ARTIN

ROUTE TO GREEKS

The key commercial and communication route be-

tween Kievan Rus and Byzantium, and called “The

Way From the Varangians [Vikings] to the Greeks”

ROUTE TO GREEKS

1305

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

in the Russian Primary Chronicle, this riverine route

began in the southeastern Baltic at the mouth of

the Western Dvina, connecting to the upper Dnieper

at portage areas near Smolensk, and continued

through Kiev to the lower Dnieper, where it entered

the Black Sea, finally terminating in Constantino-

ple. An alternative route in the north passed from

Smolensk portages to the Lovat, which led to Lake

Ilmen and, via the Volkhov and Novgorod, on to

Lake Ladoga and thence, by way of the Neva, to

the Gulf of Finland and the eastern Baltic. While

segments of this route were used from the Stone

Age onward, it did not achieve its fullest extent un-

til the late ninth and early tenth centuries when

Rus princes unified the waterways and adjoining

lands under the Rus state.

In the mid-tenth century, the Byzantine em-

peror Constantine Porphyrogenitus described (De

administrando imperio) the southern part of the

route, noting the existence of seven cataracts in the

lower Dnieper, passable only by portage, and the

attendant dangers of Pecheneg attacks. According

to Constantine, the Slavs—from as far north as

Novgorod—cut monoxyla (dugouts) during the

winter and floated them downstream to Kiev in

spring. There, these boats were rebuilt and equipped

with oars, rowlocks, and “other tackle.” In early

summer, the Rus filled these boats with goods to

sell in Constantinople and rowed downstream to

the island of St. Aitherios (Berezan) in the mouth

of the Dnieper, where they again re-equipped their

boats with “tackle as is needed, sails and masts and

rudders which they bring with them.” Thereafter,

they sailed out into the Black Sea, following its

western coast to Constantinople. With the Rus-

Byzantine commercial treaties of 907, 911, 944,

and 971, Rus traders were common visitors in Con-

stantinople, where they stayed for as long as six

months annually, from spring through the sum-

mer months, at the quarters of St. Mamas.

The Rus traded furs, wax, and honey for

Byzantine wine, olive oil, silks, glass jewelry and

dishware, church paraphernalia, and other luxu-

ries. During the tenth century and perhaps a bit

later, the Rus also sold slaves to the Byzantines.

Rus and Scandinavian pilgrims and mercenaries

also traveled to the eastern Mediterranean via this

route. On several occasions in the tenth century

and in 1043, the Rus used this route to invade

Byzantium.

During inter-princely Rus disputes, the route

was sometimes closed, as at the turn of the twelfth

century when Kiev blockaded trade with Novgorod.

On occasion, nomadic peoples south of Kiev also

blocked the route or impeded trade, and Rus princes

responded with military expeditions. With the oc-

cupation of Constantinople by Latin Crusaders in

1204, Rus merchants shifted their trade to the

Crimean port of Sudak. The route was abandoned

following the Mongol conquest of Rus in about

1240. However, up to that time, Kiev’s trade via

the route flourished, particularly from the eleventh

to the mid-thirteenth centuries.

See also: BYZANTIUM, INFLUENCE OF; FOREIGN TRADE;

KIEVAN RUS; NORMANIST CONTROVERSY; PRIMARY

CHRONICLE; VIKINGS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cross, Samuel Hazzard and Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd

P., tr. and ed. (1973). The Russian Primary Chronicle.

Cambridge, MA: Mediaeval Academy of America.

Kaiser, Daniel, tr. and ed. (1992). The Laws of Russia, Se-

ries 1, Vol. 1: The Laws of Rus’, Tenth to Fifteenth Cen-

turies. Salt Lake City, UT: Charles Schlacks, Jr.

Noonan, Thomas S. (1967). “The Dnieper Trade Route.”

Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Noonan, Thomas S. (1991). “The Flourishing of Kiev’s

International and Domestic Trade, ca. 1100–ca.

1240.” In Ukrainian Economic History: Interpretive Es-

says, ed. I. S. Koropeckyj. Cambridge, MA: Ukrain-

ian Research Institute.

R

OMAN

K. K

OVALEV

RSFSR See RUSSIAN SOVIET FEDERATED SOCIALIST RE-

PUBLIC.

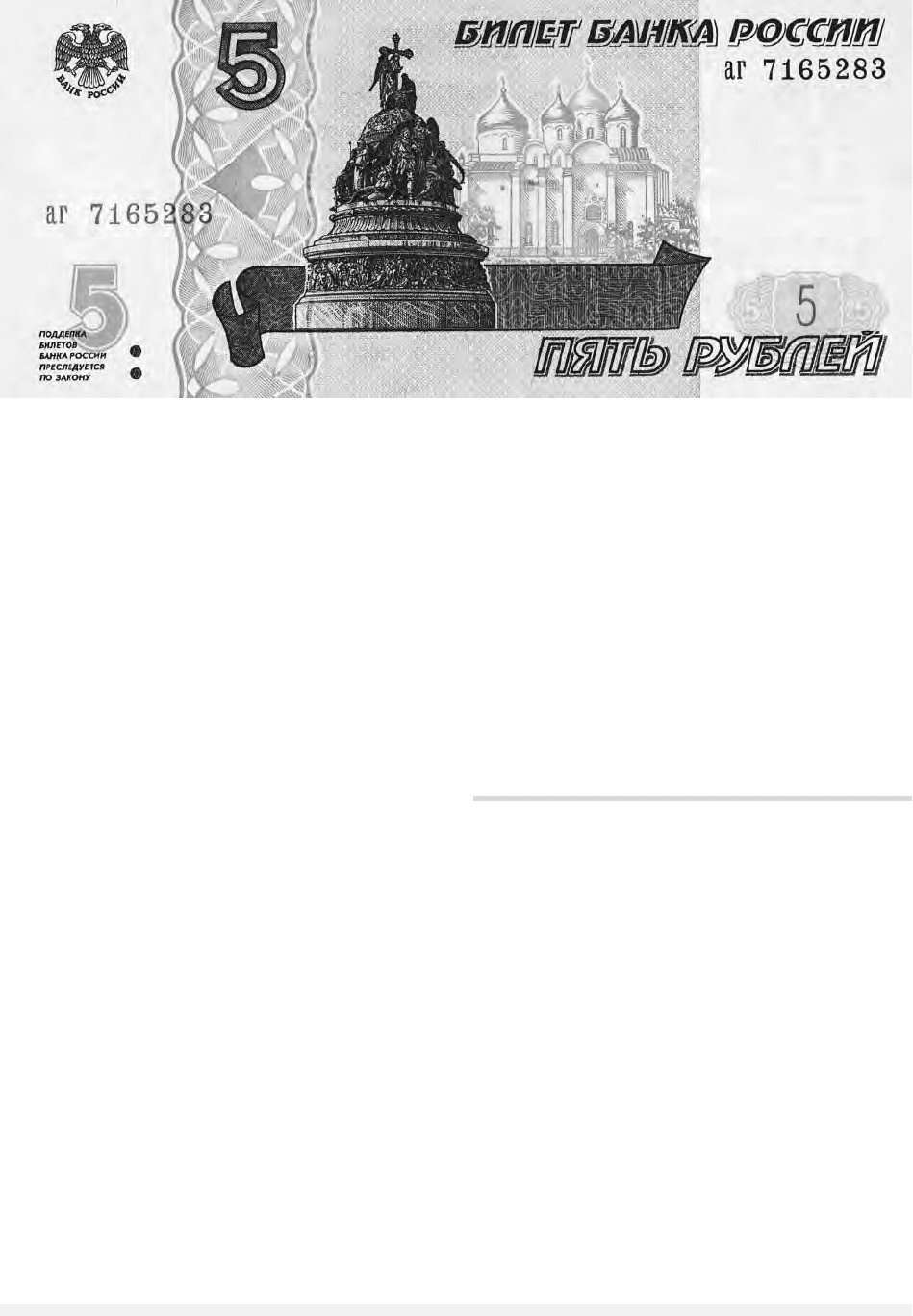

RUBLE

The basic unit of Russian currency.

The term ruble (rubl’) emerged in thirteenth-

century Novgorod, where it referred to half of a

grivna. The term derives from the verb rubit (to

cut), since the original rubles were silver bars

notched at intervals to facilitate cutting. The ruble

was initially a measure of both value and weight,

but not a minted currency. Under the monetary

reform of 1534, the ruble was defined as equal to

100 kopecks or 200 dengi. Other subdivisions of

the ruble were the altyn (3 kopecks), the grivennik

(10 kopecks), the polupoltina (25 kopecks), and the

RSFSR

1306

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

poltina (50 kopecks). A highly inflationary copper

ruble circulated during Alexei Mikhailovich’s cur-

rency reform (1654–1663), the first instance of

minted ruble coins.

In 1704 the government began the regular

minting of silver rubles, defined initially as equal

to 28 grams of silver but declining steadily to 18

grams by the 1760s. Gold coins were minted in

1756 and 1779, copper rubles in 1770 and 1771.

From 1769 to 1849, irredeemable paper promis-

sory notes called assignatsii (sing. assignatsiya) cir-

culated alongside the metal currency.

Nicholas I reestablished the silver ruble as the

basic unit of account. In 1843 he introduced a new

paper ruble that remained convertible only until

1853. In 1885 and 1886, the silver ruble, linked

to the French franc, was reinstated as the official

currency. Sergei Witte’s reforms in 1897 intro-

duced a gold ruble, and Russia remained on the

gold standard until 1914. Fully convertible paper

currency circulated at the same time. A worthless

paper ruble (kerenka) was used at the close of

World War I.

The first Soviet ruble—a paper currency—was

issued in 1919, and the first Soviet silver ruble ap-

peared in 1921. Ruble banknotes were introduced

in 1934. A 1937 reform set the value of the ruble

in relation to the U.S. dollar, a practice that ended

in 1950 with the adoption of a gold standard. Mon-

etary reforms were implemented in 1947, 1961,

and 1997.

See also: ALTYN; DENGA; GRIVNA; KOPECK; MONETARY

SYSTEM, SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Spassky, Ivan Georgievich. (1968). The Russian Monetary

System: A Historico-Numismatic Survey, tr Z. I. Gor-

ishina and rev. L. S. Forrer. Amsterdam: J. Schul-

man.

J

ARMO

T. K

OTILAINE

RUBLE CONTROL

The Soviet economy was predominantly centrally

controlled, with production and supply targets set

using physical indicators or quasi-physical units,

and with prices fixed according to criteria that were

far removed from any consideration of the demand

and supply equilibrium. Given the dual monetary

circulation in the economy, only physical or quasi-

physical units were to be used inside the state sec-

tor. Households, on the other hand, participated in

a mostly fixed-price cash economy. Central control

of monetary units was called ruble control. It aimed

both at the quasi-physical monetary units used for

decision-making within the state sector and the

mostly fixed-price monetary units that the house-

hold sector faced.

In the broad sense of the phrase, ruble control

thus included central control over any activities

RUBLE CONTROL

1307

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

A five-ruble Russian banknote. TNA A

SSOCIATES

.

that used monetary units. This primarily encom-

passed prices, wages, costs, profits, investment, and

finance, as well as credits. Because the use of mon-

etary units is broadly pervasive in a multiresource

and multiproduct economy, the field of ruble con-

trol was extensive, even in a centrally managed

economy. In addition to being another general con-

trol tool, ruble control was supposed to focus on

improving efficiency and equilibrium in the econ-

omy. The more the economy moved from direct

central control of entrepreneurial and other behav-

iors to the more indirect control based on prices and

other monetary units, the more the importance of

ruble control tended to grow. However, the mon-

etary units used were administratively determined,

and enterprises had soft budget constraints with

little real decision-making independence, so that ru-

ble control remained just one more way of imple-

menting central management, and did not become

an element of market relations.

Because the centrally managed economy had a

wide variety of monetary units, ruble control also

had a large number of subjects, from business en-

terprises to governmental ministries to the State

Bank. The variety of controlling agencies and their

always badly defined prerogatives, as well as the

inevitable divergence of interests among these dis-

parate groups, meant that ruble control was far

from an optimal management tool. Different con-

trollers sent different or even contradictory com-

mands, giving subordinated units at least some

decision-making room. Businesses had an impact

at the planning stage on the directives and para-

meters that would ultimately be given to them. In

addition, since these enterprises had soft budget

constraints, the availability of finance was not a

binding constraint if a priority target threatened to

go unfulfilled. This is because, although costs were

theoretically under ruble control, they could be ex-

ceeded if necessary in order to meet output targets.

Soviet leaders thought they could well accept inef-

ficiency if that helped them to reach goals with a

higher priority, because they believed that resources

were in almost unlimited supply. In other words,

central management was based on priority think-

ing, and ruble control had to accommodate the es-

tablished priorities.

The negative consequences of this logic were

visible from the very beginning of central man-

agement. Already by 1931, many proposals were

circulated for enhancing ruble control. Among

these were more rational pricing, fuller cost-

accounting, and better coordination of different

controls, as well as increased decentralization, at

least in plan fulfillment. It is revealing about the

priority-planning logic that very similar, even iden-

tical proposals for rationalizing central manage-

ment were put forward during all the waves of

Soviet reform discussion until the 1980s. Still, in

the early 1980s the system functioned very much

as it had fifty years earlier, with one crucial dif-

ference: Mass terror had been abolished and in-

creased consumption had become a priority. On one

hand, this had made ruble control more important.

On the other, by weakening other controls and by

increasing the autonomy both of managers and

households, these developments had made ruble

control more difficult. There were markets and

quasi-markets, but market-based policy instru-

ments remained absent.

See also: HARD BUDGET CONSTRAINTS; MONETARY SYS-

TEM, SOVIET; REPRESSED INFLATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kornai, Janos. (1992). The Socialist System. Oxford: Ox-

ford University Press.

Nove, Alec. (1977). The Soviet Economic System, 2nd edi-

tion. London: Allen & Unwin.

P

EKKA

S

UTELA

RUBLEV, ANDREI

(c. 1360–1430), fifteenth century Russian artist.

Among all the known icon painters in Russian

history, Andrei Rublev stands out as most promi-

nent. Early in his life he joined the Trinity-Sergius

Lavra Monastery, becoming a monk and a pupil of

the artist Prokhor of Gorodets. Later he moved near

Moscow, to the Spaso Andronikov Monastery,

where he died on January 29, 1430, after painting

frescoes in that monastery’s Church of the Savior.

He was buried in the altar crypt beside the artist,

Daniel Chorni.

Rublev is considered the founder of the Moscow

School of painting. The earliest reference to Rublev’s

work is to paintings in the Annunciation Cathedral

of the Moscow Kremlin. Here in 1405 he worked

with the eminent Theophanes the Greek (who

strongly influenced his style) and the monk

Prokhov of Gorodets. On the iconostasis (the screen

separating the church nave from the altar area)

Rublev is credited with the scenes of the annunci-

RUBLEV, ANDREI

1308

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ation to the Virgin Mary and scenes from the life

of Christ that show his nativity, baptism, trans-

figuration, the resurrection of Lazarus, entry into

Jerusalem, and the presentation in the Temple.

Rublev worked extensively outside of Moscow

as well. In about 1400, in the Dormition Cathedral

on Gorodok in Zvenigorod, Rublev, assisted by

Daniel Chroni, painted a number of wall frescoes,

including those of St. Laurus and St. Florus, and

several panel icons, including Archangel Michael,

Apostle Paul, and the Christ. In the Cathedral of

the Dormition in Vladimir, assisted again by Daniel

Chorni, he painted frescoes of the Last Judgment

in 1408. He is also credited with five surviving

icons.

The last reference to Rublev’s work refers to his

work on the iconostasis in the Cathedral of the

Trinity at Zagorsk (Trinity-Sergius Monastery),

where he was assisted once again by Daniel Chorni.

It was here that he produced his most famous icon,

the Old Testament Trinity (1411; now in the

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow). Ordered by Nikon

and painted in honor of Father Sergius of Radonezh

(d. 1392), it was originally displayed at the latter’s

grave. The ethereal and beautifully-integrated

group of three angels has never been surpassed. Of

the other icons on this iconostasis, Rublev was cred-

ited with those depicting the Archangel Gabriel, St.

Paul, and the Baptism of Christ. Rublev is believed

to have painted two more icons for other venues:

a Christ in Majesty (c. 1411, now at the Tretyakov

Gallery) and a version of the Vladimir Mother of

God (c. 1409, Vladimir Museum).

Rublev’s fame continued to increase after his

death. The Church Council held in Moscow in 1551

prescribed the official canon for the correct repre-

sentation of the Trinity: “. . . to paint from ancient

models, as painted by the Greek painters and as

painted by Andrei Rublev.” It is the other-worldly,

spiritual, and contemplative quality of Rublev’s

painting that sets him apart from his contempo-

raries. His Old Testament Trinity has had by far

had the strongest impact on subsequent icon paint-

ing up through the twentieth century, not only in

the Russian Orthodox Church, but in Catholic and

Protestant circles as well. In Soviet Russia, gifted

filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky produced an epic-

length, classic film titled Andrei Rublev in 1966. It

was widely acclaimed, and continues to be shown

in art theaters and at Russian conferences.

See also: DIONISY; ICONS; THEOPHANES THE GREEK

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lazarev, Viktor Nikitich. (1966). Old Russian Murals &

Mosaics from the XI to the XVI Century. London:

Phaidon.

Lazarev, Viktor Nikitich. (1980). Moscow School of Icon

Painting. Moscow: Iskusstvo.

A. D

EAN

M

C

K

ENZIE

RUBLE ZONE

“Ruble zone” refers to the accidental currency union

that emerged when the Soviet Union broke up in

December 1991, after which several independent

states (former republics) each used the ruble as their

primary currency. This sparked an intense debate

among the Central Bank of Russia (CBR), the Russ-

ian government, the other post-Soviet govern-

ments, and the international financial institutions

over the pros and cons of retaining the ruble zone.

The ruble zone at first encompassed all fifteen for-

mer Soviet republics, grew progressively smaller

through 1992 and 1993 as the new states intro-

duced their own currencies, and disappeared com-

pletely in 1995 when Tajikistan adopted the Tajik

ruble as its sole legal tender. The three Baltic states,

having no intention of staying in the ruble zone,

introduced their own currencies in mid-1992, but

the other post-Soviet states initially chose to re-

main.

The ruble zone’s existence presented a signifi-

cant dilemma for the CBR, because it prevented the

CBR from controlling the Russian money supply.

Only the CBR could print cash rubles, because all

of the printing presses were on Russian territory.

However, a legacy of the Soviet-style currency sys-

tem (called the dual monetary circuit) allowed any

central bank in the ruble zone to freely issue ruble

credits to its domestic banks. These banks then

loaned the credits to domestic enterprises, which

could in turn use them to purchase goods from

other ruble zone states (primarily Russia). In effect,

the ruble zone states self-financed their trade

deficits with Russia through these credit emissions.

In addition, several ruble zone states issued so-

called “coupons” or parallel currencies to circulate

alongside the ruble in 1992 and 1993, thereby in-

creasing the cash money supply in the ruble zone

as well.

In an attempt to mitigate the impact of this

credit expansion on the Russian economy, as of

RUBLE ZONE

1309

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

July 1992 the CBR began keeping separate ruble

credit accounts for each state. In August 1992 it

announced that Russian goods could be purchased

only with CBR-issued credits, and it suspended the

other banks’ credit-granting privileges entirely in

May 1993. During this process, Ukraine and Kyr-

gyzstan left the ruble zone. The CBR then fatally

undermined the ruble zone through a currency re-

form in July 1993. It began to print new Russian

ruble notes (circulating at equivalency with the old

Soviet ones) in early 1993, but did not send these

new rubles to the other states; they received their

cash shipments solely in Soviet rubles. On July 24,

the CBR announced that all pre-1993 ruble notes

would become invalid in Russia, forcing the other

ruble zone members either to leave or to cede all

monetary sovereignty to the CBR. Azerbaijan and

Georgia left the ruble zone immediately, while

Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Turk-

menistan, and Uzbekistan left in November 1993

after talks on creating a ruble zone of a new type

broke down. Although this effectively destroyed the

ruble zone, its formal end came in May 1995 when

war-torn Tajikistan finally introduced its own cur-

rency.

See also: MONETARY SYSTEM, SOVIET; RUBLE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abdelal, Rawi. (2001). National Purpose in the World Econ-

omy: Post-Soviet States in Comparative Perspective.

Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Chavin, James. (1995). “The Disintegration of the Soviet

Ruble Zone, 1991–1995.” Ph.D. diss. Berkeley, CA:

University of California, Berkeley.

Goldberg, Linda; Ickes, Barry; and Ryterman, Randi.

(1994). “Departures from the Ruble Zone: The Im-

plications of Adopting Independent Currencies.”

World Economy 17 (3):239–322.

Johnson, Juliet. (2000). A Fistful of Rubles: The Rise and

Fall of the Russian Banking System. Ithaca, NY: Cor-

nell University Press.

J

ULIET

J

OHNSON

RUMYANTSEV, PETER ALEXANDROVICH

(1725–1796), military commander, from 1774

known as Rumiantsev-Zadunaisky for his military

victories “across the Danube.”

Peter Alexandrovich Rumyantsev was the son

of Alexander Ivanovich Rumyantsev, who rose to

prominence in the circle of Peter I, and Maria An-

dreyevna Matveyeva, whose father was an am-

bassador and senator. Early in the reign of Empress

Anna (1730–1740), the Rumyantsevs fell from fa-

vor, but Alexander resumed service in 1735 and

was rewarded with the hereditary title of count. In

1748 Peter Rumyantsev married Princess Ekaterina

Mikhailovna Golitsyna, with whom he had three

sons, Mikhail, Nikolai, and Sergei. He was es-

tranged from his wife early in the marriage.

Despite earning a reputation for dissolute be-

havior, young Peter Rumyantsev received several

commissions in the army. He served with distinc-

tion in the Seven Years’ War (1756-1762), com-

manding a cavalry regiment during several

successful Russian actions. Having been promoted

by Emperor Peter III, he expected to be exiled when

Catherine II (r. 1762-1796) seized power, but in

1764 she made him governor–general of Ukraine,

with the task of integrating that territory into the

Russian administrative and fiscal system. He car-

ried out a major survey and census, introduced a

new postal system and courts, and revised laws on

peasants. In 1767 he was summoned to participate

in the Legislative Commission and was required to

investigate Ukrainian delegates to minimize claims

for independent privileges and institutions for the

region.

At the outbreak of the Russo–Turkish war in

1768, Rumyantsev was first given command of

Russia’s Second Army and charged with the re-

sponsibility of guarding the southern borders. He

then took over the First Army from Prince Alexan-

der Mikhailovich Golitsyn. He won victories in July

1770 at Larga and Kagul against great odds and

went on to capture towns in Ottoman-held Mol-

davia and Wallachia. In 1771 he moved west to the

Danube, and in 1773 he laid siege to towns in the

region but was forced to retreat by supply diffi-

culties. In 1774 Rumyantsev’s forces outmaneu-

vered the Turkish vizier and forced him to accept

peace terms at Kuchuk Kainardji.

Rumyantsev was made a field marshal and re-

ceived the orders of St. George and St. Andrew, as

well as lavish rewards that included landed estates.

He returned to Ukraine to implement Catherine’s

Provincial Reform (1775). In the second Russo–

Turkish War (1787–1792) Rumyantsev commanded

the Ukrainian army, but was in the shadow of

Grigory Potemkin. His last major campaign was in

Poland in 1794 against Tadeusz Kosciusko. When

he died, Emperor Paul ordered three days mourn-

ing in the army in his honor.

RUMYANTSEV, PETER ALEXANDROVICH

1310

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

See also: MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA; RUSSO-TURKISH WARS;

SEVEN YEARS’ WAR

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, John T. (1983). “Rumiantsev, Petr Aleksan-

drovich.” In Modern Encyclopedia of Russian and So-

viet History, edited by Joseph L. Wieczynski, vol. 31,

15-19. Gulf Breeze, FL: Academic International Press.

L

INDSEY

H

UGHES

RURIK

(d. 879), Varangian (Viking) leader who established

his rule over the Eastern Slavs in the Novgorod re-

gion and became the progenitor of the line of

princes, the Rurikid dynasty (Rurikovichi), that

ruled Kiev and Muscovy.

The Primary Chronicle reports that a number of

Eastern Slavic tribes quarreled but agreed to invite

a prince to come and rule them and to establish

peace. They sent their petition overseas to the

Varangians called the Rus. In 862 three brothers

came with their kin. Sineus occupied Beloozero and

Truvor took Izborsk, but they died within two

years. Consequently Rurik, who initially may have

ruled Staraya Ladoga, made Novgorod his capital

and asserted his control over the entire region. He

sent men to Polotsk, Rostov, Beloozero, and

Murom. In doing so, he controlled the mayor river

routes carrying trade between the Baltic to the

Caspian Seas. Rurik allowed two boyars, Askold

and Dir, to go to Constantinople; on the way they

captured Kiev. In 879, while on his deathbed, Rurik

handed over authority to his kinsman Oleg and

placed his young son Igor into Oleg’s custody.

The chronicle information about the semi-

legendary Rurik has been interpreted in various

ways. For example, the so-called Normanists accept

the reliability of the chronicle information show-

ing that the Varangians, or Normans, founded the

first Russian state, but the so-called Anti-Norman-

ists look upon the chronicle reports as unreliable if

not fictitious. Some identify Rurik with Rorik of

Jutland, who was based in Frisia. Significantly, other

written sources and archaeological evidence neither

prove nor disprove the chronicle information.

See also: KIEVAN RUS; NOVGOROD THE GREAT; RURIKID

DYNASTY; VIKINGS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Franklin, Simon, and Shepard, Jonathan. (1996). The

Emergence of Rus 750–1200. London: Longman.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

RURIKID DYNASTY

Ruling family of Kievan Rus, the northern Rus prin-

cipalities, and Muscovy from the ninth century to

1598.

The Rurikid dynasty ruled the lands of Rus

from the ninth century until 1598. The dynasty

was allegedly founded by Rurik. According to an

account in the Primary Chronicle he and his broth-

ers, called Varangian Rus, were invited in 862 by

East Slav and Finn tribes of northwestern Russia to

rule them. Rurik survived his brothers to rule alone

a region stretching from his base in Novgorod

northward to Beloozero, eastward along the upper

Volga and lower Oka Rivers and southward to the

West Dvina River. Although it has been postulated

that Rurik was actually Rorik of Jutland, there is

no scholarly consensus on his identity, and the

account of his arrival is often considered semi–

legendary. Varangians or Vikings, however, had

been operating in the region as adventurers and

merchants. The tale of Rurik represents the stabi-

lization and formalization of the relationship be-

tween these groups of adventurers and the

indigenous populations.

After Rurik died (879), his kinsman Oleg (r.

882–912), acting as regent for Igor, identified as

Rurik’s young son, seized control of Kiev (c. 882),

located on the Dnieper River. From Kiev, which be-

came the primary seat of the Rurikid princes until

the Mongol invasions between 1237 and 1240, Igor

(r. 913–945), his widow Olga (r. 945–c. 964), their

son Svyatoslav (r. c. 964–972), and his son

Vladimir (r. 980–1015), replacing other Varangian

and Khazar overlords, subordinated and exacted

regular tribute payments from the East Slav tribes

on both sides of the Dnieper River and along the

upper Volga River. Their strong ties to Byzantium

resulted in Prince Vladimir’s conversion of his peo-

ple to Christianity in 988. The dynasty and the

church combined to provide a common identity to

the disparate lands and peoples of the emerging

state of Kievan Rus.

The Rurikids enlarged Kievan Rus territory and

through diplomacy, war, and marriage established

RURIKID DYNASTY

1311

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ties with other countries and royal houses from

Scandinavia to France to Byzantium. But the Rurikids

themselves were not always unified. Vladimir as

well as his son Yaroslav the Wise gained the Kievan

throne through fraticidal wars. To avoid further

succession struggles, Yaroslav wrote a testament

for his sons before he died in 1054. In it he assigned

the central princely seat at Kiev to his eldest, sur-

viving son Izyaslav. He gave other towns, which

became centers of principalities within Kievan Rus,

to his other sons while admonishing them to re-

spect the seniority of their eldest brother.

Although Yaroslav’s testament did not prevent

internecine warfare, it established a dynastic realm

shared by the princes of the dynasty. Members of

each generation succeeded one another by senior-

ity through a hierarchy of princely seats until each

in his turn ruled at Kiev. This system, known as

the rota or ladder system of succession, functioned

imperfectly. Ongoing discord combined with at-

tacks from the Polovtsy (nomads of the steppe, also

known as Kipchaks or Cumans) motivated the

princes to meet at Lyubech in 1097; they agreed

that each branch of the dynasty would rule one of

the principalities within Kievan Rus as its patrimo-

nial domain. Kiev alone remained a dynastic pos-

session.

Under this revised method of succession Svy-

atopolk Izyaslavich ruled Kiev to 1113. He was suc-

ceeded by his cousin, Vladimir Vsevolodich, also

known as Vladimir Monomakh (r. 1113–1125),

and subsequently by Monomakh’s sons. Although

the system brought order to dynastic relations, it

also reinforced division among the dynastic

branches, which was paralleled by a weakening in

the cohesion among the component principalities

of Kievan Rus.

By the end of the twelfth century the dynasty

had divided into approximately a dozen branches,

each ruling its own principality. The princes of four

dynastic lines, Vladimir–Suzdal, Volynia, Smolensk,

and Chernigov, remained in the Kievan rotational

cycle and engaged in fierce competition particularly

when the norms of succession were challenged. One

campaign, launched by Andrei Bogolyubsky of

Vladimir, resulted in the sack of Kiev in 1169. Al-

though fought to defend the traditional succession

system, this campaign is often cited as evidence of

the fragmentation of the dynasty and Kievan Rus.

When the Mongols invaded and destroyed

Kievan Rus, many members of the Rurikid dynasty

were killed in battle. Nevertheless, with the approval

of their new overlords, surviving princes continued

to rule the lands of Rus. By the mid-fourteenth cen-

tury, however, the dynasty lost possession of Kiev

and other western lands to Poland and Lithuania.

But in the northeast the princes of Moscow, a

branch of the dynasty descended from Vladimir

Monomakh’s grandson Vsevolod and his grandson

Alexander Nevsky, gained control over the princi-

pality of Vladimir-Suzdal. Symbolized by Dmitry

Donskoy’s victory at the Battle of Kulikovo (1380),

they cast off Mongol suzerainty and expanded their

realm to create the state of Muscovy.

The Moscow princes also reordered internal dy-

nastic relations. After an unsuccessful challenge to

Basil II (ruled 1425–1462) by his uncle and cousins

that resulted in an extended civil war (1430–1453),

a vertical pattern of succession firmly replaced the

traditional collateral one. Ivan III (ruled 1462–1505),

selecting his second son over his grandson (the son

of his eldest but deceased son), defined the heir to

the Muscovite throne as the eldest surviving son of

the ruling prince. Basil III (ruled 1505–1533) di-

vorced his barren wife after a twenty-year mar-

riage in order to remarry and produce a son rather

than allow the throne to pass to his brother.

Dynastic reorganization enhanced the power

and prestige of the monarchs, who formally

adopted the title “tsar” in 1547. But when Fyodor,

the son of Ivan IV “the Terrible,” died in 1598, and

left no direct heirs, the Rurikids’ seven-century rule

came to an end. After a fifteen-year interregnum,

known as the Time of Troubles, the Romanov dy-

nasty, related to the Rurikids through Fyodor’s

mother, replaced the Rurikid dynasty as the tsars

of Russia.

See also: ALEXANDER YAROSLAVICH; BASIL I; BASIL II; BASIL

III; DONSKOY, DMITRY IVANOVICH; FYODOR IVANO-

VICH; IVAN III; IVAN IV; OLEG; OLGA; RURIK; VLADIMIR

MONOMAKH; VLADIMIR, ST; VIKINGS; YAROSLAV

VLADIMIROVICH; YURY VLADIMIROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dimnik, Martin. (1978). “Russian Princes and their Iden-

tities in the First Half of the Thirteenth Century.”

Mediaeval Studies 40:157–185.

Kollmann, Nancy Shields. (1990). “Collateral Succession

in Kievan Rus.” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 14(3/4):

377–387.

J

ANET

M

ARTIN

RURIKID DYNASTY

1312

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY