Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Riasanovsky, Nicholas. (1967). Nicholas I and Official Na-

tionality in Russia, 1825–1855. Berkeley: University

of California Press.

Slezkine, Yuri. (1994). Arctic Mirrors: Russia and the Small

Peoples of the North. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University

Press.

Weeks, Theodore R. (1996). Nation and State in Late Im-

perial Russia: Nationalism and Russification on the

Western Frontier, 1863–1914. DeKalb, IL: Northern

Illinois University Press.

T

HEODORE

R. W

EEKS

RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR

After brokering the end of the Sino-Japanese War

(1894–1895) with the Treaty of Shimonoseki, Rus-

sia placed itself on a collision course with Japan

over the issue of spheres of influence in Manchuria.

Relations between the two countries further dete-

riorated in 1898, when Russia occupied the Chinese

fortress of Port Arthur (now Lu-shun), and again

in 1903, when Russian economic interest focused

on Korea. Japan’s response to Russia’s aggressive

eastern policy became apparent on February 8,

1904 when Admiral Heihachiro Togo launched a

surprise attack on Port Arthur. Having won con-

trol of the sea, the Japanese began landing land

troops at Chemulpo (now Inchon), as far north as

possible on the Korean Peninsula to avoid the bad

roads. Nonetheless, the weather did not cooperate,

and it was six weeks before General Tamemoto

Kuroki’s First Army was ready to march around

the northern tip of the Bay of Korea and invade the

Liao Tung Peninsula.

Russia, meanwhile, had entered the war un-

prepared for conflict in Asia. Its military planners

had given priority to the empire’s European fron-

tiers and had not dedicated sufficient resources to

the defense of its Asian interests. While the Japan-

ese considered mainland northeastern Asia vital to

their national security, the Russians viewed the re-

gion merely as a colonial interest for potential eco-

nomic development and wealth. No one understood

Russia’s predicament as clearly as War Minister

Alexei N. Kuropatkin, who, upon the outbreak of

war, resigned his ministerial portfolio, assumed

command of the Russian army, and proceeded to

Manchuria, where he arrived in March 1904. Since

his forces were being transferred from one end of

the empire to the other on the single-track and still

incomplete Trans-Siberian Railroad, Kuropatkin set

up defenses that he hoped would give Russia at least

three months to build up its military presence in

the Far East.

Kuropatkin began concentrating troops be-

tween Harbin and Liao Yang, but the Japanese

thwarted his plan by beginning operations in the

middle of March. The Japanese movements un-

nerved the commander of Port Arthur, General A.

M. Stoessel, who immediately appealed to Nicholas

II’s personally appointed viceroy for the Far East,

Admiral E. I. Alexiev, for help. Alexiev ordered

Kuropatkin to attack the Japanese, but the com-

mander-in-chief, holding that he was answerable

only to the tsar, refused. Thinking that Port Arthur

had supplies enough to withstand a long siege,

Kuropatkin had no intention of deviating from his

plan. Before this dispute could be resolved, the

Japanese forced Kuropatkin’s hand by defeating the

Russians in the hotly contested Battle of Nanshan

in April.

With Port Arthur’s supply lines cut after Nan-

shan, Kuropatkin no longer had the luxury of wait-

ing until an overwhelming force was assembled.

The major battles of the war followed: Va Fan Gou

(May), Liao Yang (August), and the river Sha Ho

(October), effectively concluding with Mukden in

February 1905. The Russians were soundly de-

feated in each of these battles by an enemy that

first out-thought and then outmaneuvered them.

Having concentrated three armies under the over-

all command of Marshal Iwao Oyama, the Japan-

ese were able to fight the war on their own terms.

Ironically, by the Battle of Mukden, Kuropatkin had

finally achieved numerical superiority just as the

Japanese reached the end of their material and hu-

man resources, but he, his staff, and the Russian

intelligence services never became aware of this ad-

vantage and were intimidated by the Japanese

army’s maneuverability. Further aggravating the

Russian predicament was the inexplicable capitula-

tion of Port Arthur on January 2, 1905. The situ-

ation was best described by the numerous military

observers representing most of the world’s nations,

who noted how unmotivated Russia’s army seemed

in comparison to the patriotic Japanese soldiers

with their strong sense of national mission.

A final event that captured the attention of the

world was the saga of Russia’s Baltic Fleet. By the

autumn of 1904, Russia’s Pacific Fleet lay in ruins,

and to regain control of the sea, Nicholas II ordered

the Baltic fleet to the Far East. Under the command

of Admiral Z. P. Rozhestvensky, the Baltic Fleet

sortied on October 15, 1904. Its round-the-world

RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR

1333

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR

1334

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

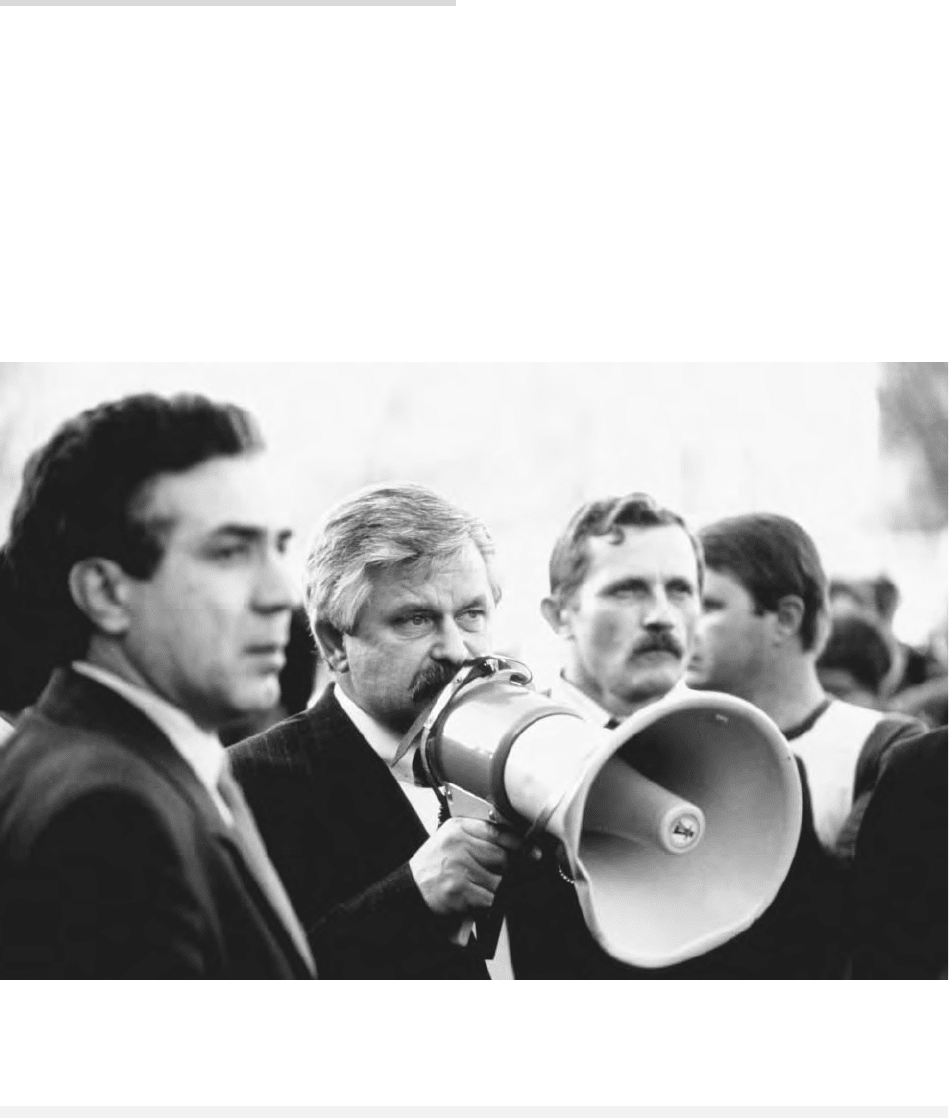

Allegory on Russo-Japanese peace treaty, concluded in Portsmouth, NH. © T

HE

A

RT

A

RCHIVE

/D

OMENICA DEL

C

ORRIERE

/D

AGLI

O

RTI

(A)

voyage attracted the interest of the international

press, which reported its attack on British fishing

vessels on the Dogger Bank (the Russians mistak-

enly imagined that they were Japanese warships),

its search to find places to refuel and refit ships that

had not been designed for such an arduous jour-

ney; and its rendezvous with reinforcements at

Madagascar. By the time the fleet arrived in Asia,

Togo was lying in wait and had little difficulty de-

feating it in the Battle of the Tsushima Straits on

May 27, 1905, which dashed Russia’s last hopes.

The Russo-Japanese War was the first global

conflict of the modern era and the first war in

which an emerging Asian nation defeated a Euro-

pean great power. The Japanese victory inflamed

Asian nationalism and contributed to the struggle

against colonialism throughout the region. The

military debacle exposed the weakness of the tsarist

regime and is usually considered the prime cause

of the Revolution of 1905. After the complete de-

feat of Russia’s land and naval forces, the tsar sued

for peace. U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt bro-

kered the Treaty of Portsmouth (August 23, 1905),

but the Japanese believed that they had lost the

peace and did not trust Western diplomacy again

until after World War II. Finally, from the techni-

cal standpoint, the Russo-Japanese War was a pre-

cursor to World War I. Both sides mobilized mass

armies and used trenches, machine guns, and rapid-

fire artillery—weapons that help define the early

twentieth century battlefield.

See also: BALTIC FLEET; JAPAN, RELATIONS WITH; KOREA,

RELATIONS WITH; KUROPATKIN, ALEXEI NIKO-

LAYEVICH; MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA; PORT ARTHUR,

SEIGE OF; PORTSMOUTH, TREATY OF; REVOLUTION OF

1905; TSUSHIMA, BATTLE OF

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Committee of Imperial Defence, Historical Section.

(1910–1920). Official History, Naval and Military, of

the Russo Japanese War. 3 vols. London: Committee

of Imperial Defence.

Connaughton, Richard M. (1988). The War of the Rising

Sun and Tumbling Bear: A Military History of the

Russo-Japanese War, 1904–05. London: Routledge.

Corbett, Julian S. (1994). Maritime Operations in the

Russo-Japanese War, 1904–05. 2 vols. Annapolis,

MD: Naval Institute Press.

German General Staff, Historical Section (1909). The

Russo-Japanese War, tr. Karl von Donat. 9 vols. Lon-

don: H. Rees.

Kinai, M., ed. (1907). The Russo-Japanese War: Official Re-

ports. 2 vols. Tokyo: Shimashido.

United States, War Department, General Staff. (1907).

Reports of Military Observers Attached to the Armies in

Manchuria during the Russo-Japanese War. 5 parts.

Washington, DC, Government Printing Office.

Walder, David. (1973). The Short Victorious War: The

Russo-Japanese Conflict, 1904–1905. New York:

Harper & Row.

Westwood, J. N. (1986). Russia against Japan, 1904–05:

A New Look at the Russo-Japanese War. Albany: State

University of New York Press.

J

OHN

W. S

TEINBERG

RUSSO-PERSIAN WARS

Disputes over territories along the southwestern

coast of the Caspian Sea and in the eastern Tran-

scaucasus led to war between Russia and Persia

from 1804 to 1813 and again from 1826 to 1828.

The military conflict between the two empires was

nothing new, but it entered a more decisive stage

with the dawning of the nineteenth century. At the

root of the first Russo-Persian War was the desire

of Shah Fath Ali to secure his northwestern terri-

tories in the name of the Qajar dynasty. At the

time, Persia’s claims to Karabakh, Shirvan, Talesh,

and Shakki seemed precarious in the wake of Rus-

sia’s annexation in 1801 of the former kingdom of

Georgia, also claimed by Persia. Meanwhile, Russia

consolidated this acquisition and resumed its mili-

tary penetration of border territories constituting

parts of modern Azerbaijan and Armenia, with the

objective of extending its imperial frontiers to the

Aras and Kura rivers.

War broke out when Prince Paul Tsitsianov

marched to Echmiadzin at the head of a column of

Russian, Georgian, and Armenian troops. The out-

numbered Russian army was unable to overcome

the town’s stubborn defense and several weeks later

also unsuccessfully besieged Yerevan. Throughout

the war, the Russians generally had the strategic

initiative but lacked the strength to crush the Per-

sian resistance. Able to commit only about ten

thousand troops, a fraction of their total force in

the Caucasus, the Russian commanders relied on

superior tactics and weapons to overcome a nu-

merical disadvantage of as much as five to one.

Overlapping wars with Napoleonic France, Turkey

(1806–1812), and Sweden (1808–1809), as well

as sporadic tribal uprisings in the Caucasus, dis-

tracted the tsar’s attention. Yet state-supported,

centralized military organization provided Russian

RUSSO-PERSIAN WARS

1335

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

columns with considerable combat power. In con-

trast, the Persian forces were largely irregular

cavalry raised and organized on a tribal basis. Ab-

bas Mirza, heir to the throne, sought French and

British instructors to modernize his army, and re-

sorted to a guerrilla strategy that delayed the Per-

sian defeat.

In 1810, the Persians proclaimed a holy war,

but this had little effect on the eventual outcome.

The Russian victories at Aslandaz in 1812 and

Lankarin in 1813 sealed the verdict in Russia’s fa-

vor. Under the Treaty of Golestan, Russia obtained

most of the disputed territories, including Dages-

tan and northern Azerbaijan, and reduced the local

khans to the status of vassals.

Another war between Russia and Persia broke

out in 1826 following the death of Alexander I and

the subsequent Decembrist revolt. Sensing oppor-

tunity, the Persians invaded in July at the instiga-

tion of Abbas Mirza, and even won some early

victories against the outnumbered forces of Gen-

eral Alexei Yermolov, whose appeals to St. Peters-

burg for reinforcements went unfulfilled. With

only twelve regular battalions, the Russians effec-

tively delayed the Persian advance. A contingent

of about eighteen hundred, for instance, held the

strategic fortress at Shusha against a greatly su-

perior force. On September 12, a Persian army un-

der the personal command of Abbas Mirza was

defeated at Yelizabetpol. In the spring of 1827, the

Russian command passed to General Ivan Paske-

vich. He captured Yerevan at the end of September

and crossed the Aras River to seize Tabriz. In

November, Abbas Mirza reluctantly submitted.

Under the Treaty of Torkamanchay (February

1828), Persia ceded Yerevan and all the territory up

to the Aras River and paid a twenty million ruble

indemnity.

See also: CAUCASUS; GEORGIA AND GEORGIANS; IRAN, RE-

LATIONS WITH; MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Atkin, Muriel. (1980). Russia and Iran, 1780–1828. Min-

neapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Curtiss, John S. (1965). The Russian Army under Nicholas

I, 1825–1855. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Kazemzadeh, Firuz. (1974). “Russian Penetration of the

Caucasus.” In Russian Imperialism: From Ivan the

Great to the Revolution, ed. Taras Hunczak. New

Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

R

OBERT

F. B

AUMANN

RUSSO-TURKISH WARS

Between Peter the Great’s outright accession in

1689 and the end of Romanov dynastic rule in

1917, Russia fought eight wars (1695–1696, 1711,

1735–1739, 1768–1774, 1787–1792, 1806–1812,

1828–1829, and 1877–1878) either singly or with

allies against the Ottomans. In addition, Turkey

joined anti-Russian coalitions during the Crimean

War (1854–1856) and World War I (1914–1918).

Although these conflicts often bore religious over-

tones, the fighting was primarily about power and

possessions. Early on, Russian incursions into

Poland, the Baltics, the Crimea, and the southern

steppe threatened useful Ottoman allies. By the sec-

ond half of the eighteenth century, however, the

issue between St. Petersburg and Constantinople

had become one of titanic struggle for hegemony

over the northern Black Sea and its northern and

northwestern littoral. In the nineteenth century, the

issue came to involve Russian aspirations for in-

fluence in the Balkans and the Middle East, access

to the Mediterranean through the Turkish Straits,

and hegemony over the Black Sea’s Caucasian and

Transcaucasian littoral. As the rivalry became in-

creasingly one-sided in Russia’s favor, St. Petersburg

generally advocated maintenance of an enfeebled

Turkey that would resist outside interference and

influences while supporting Russia’s interests.

Russia scored its most important successes in

the Black Sea basin during Catherine II’s First

(1769–1774) and Second (1787–1792) Turkish

Wars. In particular, three of her commanders, Pe-

ter Alexandrovich Rumyantsev, Alexander Vasile-

vich Suvorov, and Grigory Alexandrovich Potemkin,

introduced into the fight a winning combination of

resolve, assets, tactical mastery, logistics, colonists,

and military-administrative support. Subsequently,

with Imperial Russian attention and assets diverted

elsewhere, and with the increasing interference of

the European powers on Turkey’s behalf, St. Pe-

tersburg proved unable to repeat Catherine’s suc-

cesses. Outside interference was no more evident

than in the aftermath of the Russo-Turkish War of

1877–1878, when considerable Russian gains in the

Balkans were virtually erased in June–July 1878

by the Congress of Berlin.

See also: MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA; TURKEY, RELATIONS

WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aksan, Virginia H. (2002). “Ottoman Military Matters.”

Journal of Early Modern History 6 (1):52–62.

RUSSO-TURKISH WARS

1336

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Kagan, Frederick W., and Higham, Robin, eds. (2002).

The Military History of Tsarist Russia. New York: Pal-

grave.

Menning, Bruce W. (1984). “Russian Military Innova-

tion in the Second Half of the Eighteenth Century.”

War & Society 2 (1):23–41.

B

RUCE

W. M

ENNING

RUTSKOI, ALEXANDER VLADIMIROVICH

(b. 1947), vice president of the Russian Federation,

governor of Kursk Oblast, general-major of avia-

tion, Hero of the Soviet Union.

Alexander Rutskoi was born on September 16,

1947 in Kmelnitsky, Ukraine, to a professional mil-

itary family. He graduated from a pilot training

school in 1966 and joined the Soviet Air Forces. In

the 1980s he served in Afghanistan as deputy

commander, commander of the air regiment, and

deputy commander of aviation for the Fortieth

Army. He was shot down twice; the second time,

his Su-25 crashed in Pakistan, where he was in-

terned and then repatriated. In late 1988 he received

the award Hero of the Soviet Union. In 1988 and

1989 he attended the Voroshilov Military Academy

of the General Staff. In 1990 he was elected to the

Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR (Russian Federation)

and to the Central Committee of the newly orga-

nized Communist Party of the RSFSR. He displayed

a strong Russian nationalist bias and in 1991 helped

to found Communists for Democracy and sup-

ported Boris Yeltsin.

Yeltsin named Rutskoi as his vice presidential

running mate in his successful campaign for the

presidency of Russia. During the August Coup

(against Gorbachev), Rutskoi organized the defense

of the Russian White House. Yeltsin promoted him

to the rank of general-major and entrusted him

with a number of delicate issues, such as border is-

sue negotiations with Ukraine and Kazakhstan and

Chechen independence. When Yeltsin embarked

upon radical economic reforms, Rutskoi publicly

expressed his doubts concerning the direction of

RUTSKOI, ALEXANDER VLADIMIROVICH

1337

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

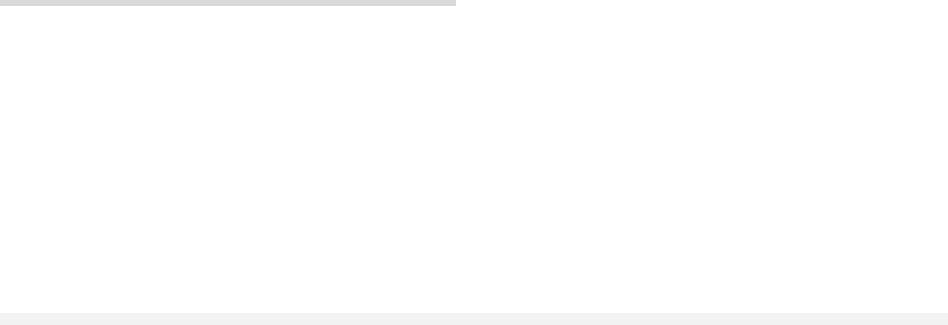

Vice President Alexander Rutskoi tries to calm the crowd as his 1993 parliamentary rebellion begins to collapse. © M

ALCOLM

L

INTON

/L

IAISON

. G

ETTY

I

MAGES

Yeltsin’s policy. Yeltsin moved to effectively isolate

his vice president. As a consequence of these devel-

opments, Rutskoi drifted toward the parliamentary

opposition led by parliament speaker Ruslan Khas-

bulatov. This struggle between president and par-

liament came to a violent head in September and

October 1993. Yeltsin crushed the revolt with

armed forces and arrested its leadership. Rutskoi

was arrested and removed from the office of vice

president, and the position of vice president was

abolished.

In 1994 the Russian parliament granted amnesty

to Rutskoi and other rebels of 1993. Rutskoi went

on to organize a Russian nationalist party, Power

(Derzhava) which competed in the 1995 parlia-

mentary elections and joined the Red-Brown oppo-

sition to Yeltsin in the summer 1996 presidential

elections. A leading figure of the anti-Yeltsin na-

tionalist opposition, Rutskoi ran for and won the

post of governor of Kursk Oblast in October 1996

and served in that office to 2000. He stood for re-

election but was disqualified by the Central Elec-

tions Commission, which ordered his name stricken

from the ballot for election campaign law viola-

tions and abuses as governor. Rumors interpreted

the government’s actions as a direct response to

Rutskoi’s criticism of the president during the Kursk

disaster.

See also: AFGHANISTAN, RELATIONS WITH; AUGUST 1991

PUTSCH; KURSK SUBMARINE DISASTER; OCTOBER 1993

EVENTS; YELTSIN, BORIS NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aron, Leon. (2000). Yeltsin: A Revolutionary Life. New

York: Thomas Dunne Books.

Chugaev, Sergei. “Khasbulatov & Co.” Bulletin of the

Atomic Scientists (January/February 1993).

J

ACOB

W. K

IPP

RYBKIN, IVAN PETROVICH

(b. 1946), chair of the State Duma in 1994 and

1995, secretary of the Security Council from 1996

to 1998, and leader of the Socialist Party of Russia.

Ivan Rybkin was born on October 20, 1946, in

the Voronezh countryside. He graduated from the

Volgograd Agricultural Institute in 1968, com-

pleted graduate school there, and worked as a

teacher until 1983. With the beginning of pere-

stroika, he launched an ambitious political career

and became the second secretary of the Volgograd

Oblast committee of the Communist Party of the

Soviet Union. In 1990, he was selected as a peo-

ple’s delegate to the RSFSR, where he headed the

Communists of Russia fraction. In 1993 and 1994

he was vice-chair of the Executive Committee of

the Communist Party of the Russian Federation

(KPRF), but in April 1994 he left the KPRF. As of

the fall of 1993, he was a member of the Agrarian

Party, on whose list he was elected to the Duma.

In this capacity he proved a pragmatic politician.

He lost the support of the leftists (in 1995 he was

excluded from the Agrarian Party), but gained the

support of the Kremlin.

In the summer of 1995, the Kremlin brought

forth an initiative to create two centrist blocs for

the elections: a right-centrist bloc headed by Pre-

mier Viktor Stepanovich Chernomyrdin, and a left-

centrist bloc. This latter subsequently came to be

called the “Ivan Rybkin bloc,” which gained 1.1 per-

cent of the electoral votes. The bloc was dissolved,

but Rybkin was nonetheless elected to the Duma by

single-mandate district in his homeland, Voronezh

Oblast. Before the second round of presidential elec-

tions, Boris Yeltsin created the Political Advisory

Council to the President of the Russian Federation,

which included representatives of parties and pub-

lic associations that had not made it into the Duma.

Rybkin, who had recently registered the Socialist

Party, was appointed chair of the council. A few

months later, Rybkin replaced Alexander Lebed as

secretary of the Security Council, in which capac-

ity he worked until 1998, focusing mainly on

Chechnya. His deputy was for some time Boris Bere-

zovsky, with whom Rybkin maintains close rela-

tions.

In 2001–2002, with the discussion and adop-

tion of the law on political parties, which required

the presence of branch offices in at least half the

regions of the country, the processes of integration

strengthened considerably. From mid-2001 on-

ward, Rybkin participated in talks concerning the

creation of a United Social-Democratic Party of

Russia, along with Mikhail Gorbachev and other

well-known politicians. The unification process

was difficult, due not so much to divergence of

views as to a clash of ambitions. In the fall of 2001,

when the process seemed complete, Rybkin’s So-

cialist Party even disbanded, in anticipation of join-

ing forces with the new party, but the merger broke

at the last minute. It was effected only in March

2002, and on a visibly more modest scale.

RYBKIN, IVAN PETROVICH

1338

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

On the basis of the Socialist Party, Alexei Pod-

berezkin’s Spiritual Heritage movement, and dozens

of small organizations with socialist tendencies, the

Socialist United Party of Russia was finally created.

Rybkin became its chair. The honeymoon period

was short, however, and within a few weeks, Ry-

bkin resigned as chair and the Socialist Party of

Russia left the coalition. In April 2003, at a con-

gress of the Socialist United Party of Russia, he was

officially removed from the position of chair and

excluded from the party. His alleged offenses in-

cluded an open letter to Putin, which called for end-

ing the Chechnya war and beginning negotiations

with Aslan Maskhadov; collaboration with the SPS;

and unsanctioned contacts with Berezovsky.

See also: CHECHNYA AND CHECHENS; PUTIN, VLADIMIR

VLADIMIROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

McFaul, Michael. (2001). Russia’s Unfinished Revolution:

Political Change from Gorbachev to Putin. Ithaca: Cor-

nell University Press.

McFaul, Michael, and Markov, Sergei. (1993). The Trou-

bled Birth of Russian Democracy: Parties, Personalities,

and Programs. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press.

McFaul, Michael; Petrov, Nikolai; and Ryabov, Andrei,

eds. (1999). Primer on Russia’s 1999 Duma Elections.

Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for Interna-

tional Peace.

Reddaway, Peter, and Glinski, Dmitri. (2001). The Tragedy

of Russia’s Reforms: Market Bolshevism against Democ-

racy. Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press.

N

IKOLAI

P

ETROV

RYKOV, ALEXEI IVANOVICH

(1881–1938), Russian revolutionary and Soviet

politician, one of the leaders of the Right opposi-

tion.

Born in Saratov province, the son of a trades-

man, Alexei Rykov joined the Social Democratic

Party in 1898 and supported the Bolsheviks after

their split with the Mensheviks. He played an ac-

tive part in the 1905 revolution. In 1907, however,

he began to work for reconciliation between the

two wings of the party. In exile in Paris for two

years, he returned to Russia in 1911 but was soon

arrested and exiled to Siberia.

Returning to Moscow after the revolution of

February 1917, Rykov became a member of the

Moscow and Petrograd soviets and participated in

the October revolution. He became commissar for

internal affairs in the first Bolshevik government,

but resigned because of his support for a coalition

government. In April 1918, however, he accepted

the post of chairperson of the Supreme Council of

the National Economy, and in February 1921 he

became deputy chairman of Sovnarkom. After

Lenin’s death in January 1924 he became chair-

man. He was also a member of the Politburo from

1922 until 1930.

Rykov was a leading supporter of the New Eco-

nomic Policy, and allied with Stalin in his struggle

with Leon Davidovich Trotsky, Grigory Yevseye-

vich Zinoviev, and Lev Borisovich Kamenev, which

lasted from 1926 to 1928. When Stalin lashed out

against the Right Opposition, of which Rykov was

one of the leaders, he was defeated, discredited, and

ultimately dismissed from his senior positions by

1930. Rykov was arrested in February 1937. With

Nikolai Alexandrovich Bukharin and Genrikh Grig-

orevich Yagoda, Rykov was one of the leading de-

fendants at the third show trial, and was executed

in March 1938.

See also: BOLSHEVISM; FEBRUARY REVOLUTION; MENSHE-

VIKS; NEW ECONOMIC POLICY; OCTOBER REVOLUTION;

POLITBURO; RIGHT OPPOSITION; SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC

WORKERS PARTY; SOVNARKOM

D

EREK

W

ATSON

RYLEYEV, KONDRATY FYODOROVICH

(1795–1826), a poet who played a leading role in

organizing the mutiny of the military units in St.

Petersburg that occurred on December 14, 1825

(the so-called Decembrist Uprising).

Born into the family of an army officer, Kon-

draty Fyodorovich Ryleyev also became an officer

and served in units stationed in West Europe after

the defeat of Napoleon’s armies. He saw the gen-

eral backwardness of Russian society sharply con-

trasted with the capitalist countries of Western

Europe. Upon returning to St. Petersburg, Ryleyev

became active in a variety of social and political cir-

cles. In 1823 he joined the secret Northern Society.

Situated in St. Petersburg and headed by Nikita

Muraviev and Sergei Trubetskoi, it consisted of

moderate reformists who leaned toward establish-

ment of a constitutional monarchy, modeled after

RYLEYEV, KONDRATY FYODOROVICH

1339

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the English version. By contrast, the Southern So-

ciety, created by Pavel Pestel in Tulchin, gathered

together more radical members of the movement,

and demanded complete eradication of the extant

tsarist autocracy and the establishment of a de-

mocratic republic based upon on universal suffrage.

With the exception of his earliest works,

Ryleyev’s poems are romantic in style. Their

themes reflect patriotic sentiments and concern

with the course of Russian history. His verses ush-

ered in ideas about the duty to sacrifice one’s artis-

tic calling in service to the downtrodden masses

well before Nikolay Nekrasov preached them in his

own poetry. Tragically, Ryleyev was not able fully

to develop his poetic talents, and his celebrity is

mainly due to the martyrdom he underwent in the

cause of freedom. He was one of the five rebels who

were executed, along with Pestel, Kakhovskoi, Mu-

raviev-Apostol, and Bestuzhev-Riumin, for their

roles in the Decembrist Uprising. His sarcastic wit

has also become legend. Apparently, just as Ryleyev

was about to be hanged, the rope broke and he fell

to the ground. Bruised and battered, he got up, and

said, “In Russia they do not know how to do any-

thing properly, not even how to make a rope.” An

accident of this sort usually resulted in a pardon,

so a messenger was sent to Tsar Nicholas to know

his pleasure. The tsar asked, “What did he say?”

“Sire, he said that in Russia they do not even know

how to make a rope properly.” “Well, let the con-

trary be proved,” said Nicholas.

See also: DECEMBRIST MOVEMENT AND REBELLION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Obolonskii, A. V., and Ostrom, Vincent. (2003). The Drama

of Russian Political History: System Against Individu-

ality. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

RYUTIN, MARTEMYAN

(1890–1937), leader of an anti–Stalin opposition

group that emerged within the Russian Commu-

nist Party in the 1930s.

Martemyan Ryutin was born on February 26,

1890, the son of a Siberian peasant from the

Irkutsk province. He joined the Bolshevik party in

1914. During the civil war, he fought against

Alexander Vasilievich Kolchak’s forces in Siberia,

and in the early 1920s he held party posts in

Irkutsk and Dagestan. In 1925, Ryutin became

party secretary in the Krasnaya Presnia district of

Moscow, and in 1927 he was elected a non-voting

member of the party Central Committee. In the

following year he incurred Stalin’s wrath for his

conciliatory attitude towards Bukharin and his fol-

lowers.

Experience of the collectivization drive con-

vinced Ryutin of the ruinous nature of Stalin’s eco-

nomic policies, and the criticisms he voiced led, at

the end of 1930, to his expulsion from the party

and a brief spell of imprisonment. In 1932, Ryutin

and some associates circulated a manifesto, “To All

Members of the Russian Communist Party,” which

condemned the Stalin regime and demanded Stalin’s

removal from power. Ryutin also composed a more

detailed analysis of Stalin’s dictatorship and eco-

nomic policies in the essay “Stalin and the Crisis of

the Proletarian Dictatorship” (first published in

1990). He was arrested, along with his group, in

September 1932. Although Stalin wanted the death

penalty, the Politburo, at the insistance of Sergei

Mironovich Kirov, rejected the demand, and Ryutin

was sentenced to ten years imprisonment. Ryutin,

however, was re-arrested in 1936 on a trumped-

up charge of terrorism, and was executed on Jan-

uary 10, 1937.

See also: KIROV, SERGEI MIRONOVICH; KOLCHAK, ALEXAN-

DER VASILIEVICH; PURGES, THE GREAT; STALIN, JOSEF

VISSARIONOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Conquest, Robert. (1990). The Great Terror: A Reassess-

ment. New York: Oxford University Press.

Getty, J. Arch, and Naumov, Oleg V. (1999). The Road

to Terror : Stalin and the Self–Destruction of the Bol-

sheviks, 1932-1939: Annals of Communism. New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Medvedev, Roy Aleksandrovich, and Shriver, George.

(1989). Let History Judge: The Origins and Conse-

quences of Stalinism. New York: Columbia Univer-

sity Press.

Tucker, Robert C. (1990). Stalin in Power: The Revolution

from Above, 1928-1941. New York: Norton.

J

AMES

W

HITE

RYZHKOV, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH

(b. 1929), USSR prime minister under Gorbachev

and a leading figure in economic reform.

RYUTIN, MARTEMYAN

1340

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Born in Donetsk Oblast, Nikolai Ryzhkov joined

the Party in 1956 and graduated from the Ural

Polytechnical Institute in Sverdlovsk in 1959. He

spent his early career as an engineer at the Or-

dzhonikidze Heavy Machine-Building Institute and

was named director in 1970. Following his suc-

cesses in the Urals, Ryzhkov became involved in

all-union economic matters.

Ryzhkov served as a deputy in the USSR Coun-

cil of the Union (1974–1979) and a deputy in

the USSR Council of Nationalities (1974–1984).

Ryzhkov was first deputy chair of the USSR Min-

istry of Heavy and Transport Machine-Building

(1975–1979) and later first deputy chair of the

USSR State Planning Commission (Gosplan)

(1979–1982). He became a full member of the CPSU

Central Committee in 1981, chairing the Diplo-

matic Department (1982–1985) and later the USSR

Council of Ministers (September 1985–December

1990), making him the de facto Soviet prime min-

ister. Ryzhkov was the chief administrator of the

Soviet economy in the last half of the 1980s. He

became a full Politburo member in April 1985 and

chaired the Central Committee Commission that

assisted victims of the 1988 Armenian earthquake.

As the economy stalled, protests grew, and the

Kremlin debated the Five-Hundred-Day Plan, Ryzh-

kov suffered a heart attack on December 25, 1990.

He subsequently resigned, and Gorbachev replaced

him with Valentin Pavlov.

Ryzhkov unsuccessfully ran against Boris

Yeltsin for the Russian presidency in June 1991. He

then assumed a variety of corporate positions, in-

cluding chairman of the board of Tveruniversal

Bank (1994–1995), chairman of the board of

Prokhorovskoye Pole, and head of the Moscow In-

tellectual Business Club. He won a seat in the Russ-

ian State Duma in 1995 and 1999 as head of

“Power to the People,” a bloc aligned with the Com-

munist Party of the Russian Federation.

See also: CENTRAL COMMITTEE; GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL

SERGEYEVICH; GOSPLAN; PERESTROIKA; POLITBURO;

PRIME MINISTER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goldman, Marshall. (1992). What went Wrong with Per-

estroika. New York: Norton.

A

NN

E. R

OBERTSON

RYZHKOV, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH

1341

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

This page intentionally left blank