Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Dunning, Chester. (2001). Russia’s First Civil War: The

Time of Troubles and the Founding of the Romanov Dy-

nasty. University Park: Pennsylvania State Univer-

sity Press.

Howe, Sonia, ed. (1916). The False Dmitri: A Russian Ro-

mance and Tragedy Described by British Eye-Witnesses,

1604–1612. London: Williams and Norgate.

Margeret, Jacques. (1983). The Russian Empire and Grand

Duchy of Muscovy: A Seventeenth-Century French Ac-

count, tr. and ed. Chester S. L. Dunning. Pittsburgh,

PA: Pittsburgh University Press.

Massa, Isaac. (1982). A Short History of the Beginnings and

Origins of These Present Wars in Moscow under the

Reigns of Various Sovereigns down to the Year 1610, tr.

G. Edward Orchard. Toronto: University of Toronto

Press.

Perrie, Maureen. (1995). Pretenders and Popular Monar-

chism in Early Modern Russia: The False Tsars of the

Time of Troubles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Platonov, S. F. (1970). The Time of Troubles, tr. John T.

Alexander. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Skrynnikov, Ruslan. (1982). Boris Godunov, tr. Hugh

Graham. Gulf Breeze, FL: Academic International

Press.

Skrynnikov, Ruslan. (1988). The Time of Troubles: Russia

in Crisis, 1604–1618, tr. Hugh Graham. Gulf Breeze,

FL: Academic International Press.

Zolkiewski, Stanislas. (1959). Expedition to Moscow, tr.

and ed. J. Giertych. London: Polonica.

C

HESTER

D

UNNING

TITHE CHURCH, KIEV

The most ancient church in Kiev was built between

989 and 996 by Prince Vladimir, who dedicated it

to the Virgin Mary and supported it with one-tenth

of his revenues. Destroyed by a fire in 1017 and

reconstructed in 1039, the church was looted in

1177 and in 1203 by neighboring princes, and it

was finally destroyed in 1240 during the siege of

Kiev by the Mongol armies of Khan Batu. Various

stories exist concerning the cause of the structure’s

collapse; as one of the last bastions of the Kievans,

it came under the assault of Mongol battering

rams, and it may have been further weakened by

the survivors’ attempt to tunnel out. Nonetheless,

part of the eastern walls remained standing until

the nineteenth century, when, in 1825, church au-

thorities decided to erect a new church on the site.

Rejecting the idea of incorporating the old walls into

the new, they leveled the existing walls down to

the foundations and commissioned the architect

Vasily Stasov to construct a neo-Byzantine church.

This church was demolished by the Soviets in 1935

and the site covered with pavement.

From twentieth-century excavations, however,

there emerged a plausible notion of the original

plan, with the arms of a cross delineated by the

aisles at the center of the church. While there is no

way of determining with any accuracy the

church’s appearance, some sense of its decoration

may be gleaned from the salvaged fragments of

mosaics, frescoes, and marble ornaments. The walls

were probably composed of alternating layers of

stone and flat brick in a mortar of lime and crushed

brick.

See also: ARCHITECTURE; CATHEDRAL OF ST. SOPHIA, KIEV;

KIEVAN RUS; VLADIMIR MONOMAKH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brumfield, William Craft. (1993). A History of Russian

Architecture. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rappoport, Alexander P. (1995). Building the Churches of

Kievan Russia. Brookfield, VT: Variorum.

W

ILLIAM

C

RAFT

B

RUMFIELD

TKACHEV, PETR NIKITICH

(1844–1886), revolutionary Russian writer.

The voluminous writings of the revolutionist

Petr Nikitich Tkachev were considered by Vladimir

Lenin to be required reading for his Bolshevik fol-

lowers. Lenin said that Tkachev, a Jacobin-Blanquist

revolutionary in Russia of the 1870s, was, “one of

us.”

Indeed, Soviet publicists in the 1920s (before

Lenin’s death) treated Tkachev, once a collaborator

of the terrorist Sergei Nechayev, as a prototypical

Bolshevik. As one writer put it, he was “the fore-

runner of Lenin.” This apposition was dropped,

however, after 1924, when Stalin introduced the

Lenin Cult. This Stalinist line did not acknowledge

any pre–1917 revolutionary as a match for Lenin’s

vaunted status as mankind’s unique, genius thinker.

The proto-Bolshevik concepts developed by

Tkachev in such publications as the illegal news-

paper Nabat (Tocsin) and in publications in France,

TKACHEV, PETR NIKITICH

1553

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

where he resided as an exile, consisted of the fol-

lowing points: 1) a revolutionary seizure of power

under Russian conditions must be the work of an

elitist group of enlightened, vanguard thinkers; to

wait for the “snail-like . . . routine-ridden” people

themselves spontaneously to adopt true revolu-

tionary ideas was a case of futile majoritarianism;

2) the revolutionary socialist elite would establish

a dictatorship of the workers and a workers’ state;

3) new generations of socialists could thus be reed-

ucated and purged of old, private-property men-

tality; 4) rejecting Hegel and his protracted dialectic,

Tkachev called for a proletarian revolution tomor-

row, claiming that to wait for private property-

mindedness to sink deeper within the Russian

population was unacceptable; instead, a revolu-

tionary jump (skachok) must be made over all in-

termediate socioeconomic stages (Tkachev parted

with the Marxists on this point, describing

Hegelianism as metaphysical rubbish); 4) to ensure

the purging of old ways, the new workers’ state

must set up a KOB (Komitet Obshchestvennoi Be-

zopasnosti), or Committee for Public Security, mod-

eled on Maximilien Robespierre’s similar committee

in striking anticipation of the Soviet Cheka, later

OGPU and KGB.

In a famous letter written to Tkachev by

Friedrich Engels, the latter disputed Tkachev on the

Tkachevist notion that Russia could become a

global pacesetter by independently making the so-

cial revolution in Russia, a backward country, in

Marxist terms, building socialism directly on the

basis of the old Russian commune (obshchina). In

his letter to Engels in 1874, Tkachev had lectured

Marx’s number one collaborator to the effect that

Karl Marx simply did not understand the Russian

situation, that Marxist strategies were “totally un-

suitable for our country.” Ironically, this allegation

became the mirror image of Georgy Plekhanov’s

point d’appui in his dispute with Russian Jacobins

in the mid-1880s, since Plekhanov, basing himself

on Hegelian historical teaching of orthodox Marx-

ism, regarded Jacobinism and Blanquism as a dis-

tortion of true Marxian revolutionism. For his part,

years later Lenin, echoing Tkachev, retorted by de-

scribing Plekhanov as a feeble, wait-and-see grad-

ualist.

When Tkachev died in a psychiatric hospital in

Paris in 1886 (he was said to have suffered paral-

ysis of the brain), the well-known Russian revolu-

tionist Petr Lavrov delivered the eulogy together

with others such as the French Blanquist Eduard

Vaillant. Years later, Tkachev’s body was disin-

terred since the cemetery plot in the Cimètiere

Parisien d’Ivry was not adequately financed. His re-

mains were cremated.

See also: BOLSHEVISM; ENGELS, FRIEDRICH; LENIN,

VLADIMIR ILICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Volkogonov, Dmitri. (1994). Lenin: A New Biography.

New York: Free Press.

Weeks, Albert L. (1968). The First Bolshevik: A Political

Biography of Peter Tkachev. New York: New York Uni-

versity Press.

A

LBERT

L. W

EEKS

TOGAN, AHMED ZEKI VALIDOV

(1890–1970), prominent Bashkir nationalist ac-

tivist during the early Soviet period and well-

known scholar of Turkic historical studies.

Born in a Bashkir village in Ufa province and

educated at Kazan University, Ahmed Zeki Validi

(Russianized as Validov) had begun a promising ca-

reer as an Orientalist scholar before the revolution.

In May 1917 Validov participated in the All Rus-

sian Muslim Congress in Moscow, where he advo-

cated federal reorganization of the Russian state and

criticized plans of some Tatar politicians for ex-

traterritorial autonomy in a unitary state. By the

end of the year, Validov had emerged as primary

leader of a small Bashkir nationalist movement that

promulgated (in December 1917) an autonomous

Bashkir republic based in Orenburg. Arrested by So-

viet forces in February 1918, Validov escaped in

April and joined the emerging anti-Bolshevik move-

ment as full-scale civil war broke out that sum-

mer. Attempts to organize the Bashkir republic and

separate Bashkir military forces under White aus-

pices flagged, particularly after Admiral Kolchak

took charge of the White movement. In February

1919 Validov and most of his colleagues defected

to the Soviet side in return for the promise of com-

plete Bashkir autonomy. However, sixteen months

of increasingly frustrating collaboration with So-

viet power ended in June 1920 when Validov de-

parted to join the Basmachis in Central Asia, hoping

to link the Bashkir search for autonomy to a larger

movement for Turkic independence from Russian

colonial rule. These hopes were dashed with Bas-

machi defeat.

TOGAN, AHMED ZEKI VALIDOV

1554

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

After leaving Turkestan in 1923, Validov taught

at Istanbul University in Turkey (1925–1932),

where he adopted the surname Togan. He went on

to earn a doctorate at the University of Vienna

(1932–1935) and taught at Bonn and Göttingen

Universities (1935–1939). Togan returned to Is-

tanbul University in 1939 and remained there un-

til his death in 1970. Togan’s scholarly output was

prodigious, with over four hundred publications,

largely in Turkish and German, on the history of

the Turkic peoples from antiquity to the twentieth

century, including his own remarkable memoirs

(Hatiralar). During these years of exile, Validov and

Validovism (validovshchina) lived on in the Soviet

lexicon as the epitome of reactionary Bashkir na-

tionalism, and accusations of connection with Vali-

dov proved fatal for hundreds if not thousands of

Bashkirs and other Muslims in Russia. Since the

early 1990s Togan’s name has been rehabilitated in

his homeland, where he is now recognized as the

father of today’s Republic of Bashkortostan.

See also: BASHKORTISTAN AND THE BASHKIRS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Paksoy, H. B. (1995). “Basmachi Movement from

Within: Account of Zeki Velidi Togan.” Nationalities

Papers 23:373–399.

Schafer, Daniel E. (2001). “Local Politics and the Birth of

the Republic of Bashkortostan, 1919–1920.” In A

State of Nations: Empire and Nation-Making in the Era

of Lenin and Stalin, ed. Ronald Grigor Suny and Terry

Martin. New York: Oxford University Press.

D

ANIEL

E. S

CHAFER

TOLSTAYA, TATIANA NIKITICHNA

(b. 1951), Russian writer.

Tolstaya is an original, captivating fiction

writer of the perestroika and post-Soviet period.

Born in 1951 in Leningrad, she graduated from

Leningrad State University with a degree in Philol-

ogy and Classics, then worked as an editor at Nauka

before publishing her first short stories in the early

1980s. Their imaginative brilliance and humane

depth won success with both Soviet and interna-

tional readers. Her activities expanded subsequently

to include university teaching (at Skidmore College,

among other institutions), journalistic writing, and

completion of a dark futuristic novel, The Slynx.

Tolstaya’s initial impact on Russian letters was

made by a series of short stories centering on the

conflict between imagination, spirit, and value, on

the one hand, and a bleak social order of confor-

mity and consumerism, cultural and spiritual

degradation, and rapacious and cynical material-

ism on the other. Although she draws on the tex-

ture of late Soviet reality with witty, acerbic

penetration, her critique of modern society travels

well. The mythical dimensions of this conflict are

highlighted in her stories by frequent use of fan-

tastic elements and folkloric allusions, such as the

transformation of the self-centered Serafim into

Gorynych the Dragon (Serafim), or the bird of

death, Sirin, symbolizing Petya’s loss of innocence

in “Date with a Bird.”

Her most notable stories are works of virtuosic

invention. Denisov of the Dantesque “Sleepwalker

in the Mist” awakens in mid-life surrounded by

dark woods and takes up the search for meaning;

his various attempts at creation, leadership, and

sacrifice ending in farce. Peters of “Peters” is a

lumpish being without attraction or charm (one

coworker calls him “some kind of endocrinal dodo”)

who spends his life in quixotic search of romantic

love; in old age, beaten down by humiliation, he

triumphs by his praise of life: “indifferent, un-

grateful, lying, teasing, senseless, alien—beautiful,

beautiful, beautiful.” Sonia of “Sonia” is a half-

witted, unattractive, but selfless creature, tormented

by her sophisticated friends through the fiction of

a married admirer, Nikolai, whom she can never

meet. The fabrication is kept up through years of

correspondence in which the chief tormentor, Ada,

finds her womanhood irresistibly subverted. In the

Leningrad blockade Sonia gives her life to save

Ada/Nikolai, without realizing the fiction.

The fantastic elements in Tolstaya’s works

have led to comparisons with the magical realism

of modern Latin American fiction, comparisons

which are only roughly valid. The association of

Tolstaya’s work with the women’s prose (zhen-

skaya proza) of late Soviet literature also requires

qualification: although women are frequently pro-

tagonists in her stories as impaired visionaries and

saints, they are just as often the objects of bitter

satire, implacable enforcers of social conventional-

ity.

Tolstaya’s remarkable novel The Slynx depicts

a post-nuclear Moscow populated by mutants,

combining the political traits of the Tatar Yoke and

Muscovite Russia with characteristics of Stalinist

TOLSTAYA, TATIANA NIKITICHNA

1555

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

and later Soviet regimes. The narrative, displaying

to advantage Tolstaya’s humor and ear for popu-

lar language, presents a negative Bildungsroman.

The uncouth but decent and robust protagonist,

Benedikt, given favorable circumstances including

a library, leisure to read, and friends from the ear-

lier times, fails to develop and cross the line from

animal existence to spiritual, and as a consequence

the culture itself fails to regain organic life. This

pessimistic historical vision seems rooted in the dis-

appointments of post-Soviet Russian political and

social life.

See also: PERESTROIKA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goscilo, Helena. (1996). The Explosive World of Tatyana

N. Tolstaya’s Fiction. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Tolstaya, Tatiana. (1989). On the Golden Porch, tr. An-

tonina W. Bouis. New York: Knopf.

Tolstaya, Tatiana. (1992). Sleepwalker in a Fog, tr. Jamey

Gambrell. New York: Knopf.

Tolstaya, Tatiana. (2003). Pushkin’s Children: Writings on

Russia and Russians, tr. Jamey Gambrell. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin.

Tolstaya, Tatiana. (2003). The Slynx, tr. Jamey Gambrell.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

H

AROLD

D. B

AKER

TOLSTOY, ALEXEI KONSTANTINOVICH

(1817–1875), writer of drama, fiction, and poetry;

considered to be the most important nineteenth-

century Russian historical dramatist.

A member of the Russian nobility, Alexei Tol-

stoy was expected to serve at court and in the diplo-

matic service, which prevented him from writing

full time until relatively late in his life (1861). Nev-

ertheless, he managed to produce a novel (Prince

Serebryanny, 1862) and a dramatic trilogy (The Death

of Ivan the Terrible, 1866; Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich,

1868; Tsar Boris, 1870), both based on the time of

Ivan the Terrible. Although, by the time Prince Sere-

bryanny was published, the fad for historical nov-

els had long passed, it nevertheless enjoyed some

popularity. Due to censorship restrictions, only the

first of the three plays was performed during the

author’s lifetime, but all three were produced nu-

merous times during the Soviet period. For all these

works, Tolstoy relied on Karamzin’s History of the

Russian State, from which he lifted passages verba-

tim for his own work.

Tolstoy’s lyric poetry, most notably “Against

the Current” (1867) and “John Damascene” (1858),

were strongly influenced by German romanticism.

He also wrote satirical verse. Collaborating with the

Zhemchuzhnikov brothers, he created the fictional

writer Kozma Prutkov, a petty bureaucrat who

parodied the poetry of the day and wrote banal

aphorisms. Karamzin’s History also served as the

inspiration for Tolstoy’s History of the Russian State

from Gostomysl to Timashev, a parody of Russian

history from its founding until 1868, which con-

tained vicious characteristics of the Russian

monarch. The manuscript circulated privately be-

tween 1868, when it was completed, and 1883,

when it first appeared in print.

See also: KARAMZIN, NIKOLAI MIKHAILOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bartlett, Rosamund. (1998). “Aleksei Konstantinovich

Tolstoi 1817–1875.” In Reference Guide to Russian Lit-

erature, ed. Neil Cornwell, 806–808. London: Fitzroy

Dearborn Publishers.

Dalton, Margaret. (1972). A. K. Tolstoy. New York:

Twayne.

E

LIZABETH

J

ONES

H

EMENWAY

TOLSTOY, LEO NIKOLAYEVICH

(1828–1910), Russian prose writer and, in his later

years, dissident and religious leader, best known for

his novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina.

CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH (1828–1852)

The fourth son of Count Nikolai Ilich Tolstoy and

Princess Maria Nikolaevich Volkonskaya, Tolstoy

was born into the highest echelon of Russian no-

bility. Despite the early deaths of his mother (1830)

and father (1837), Tolstoy led the typically idyllic

childhood of a nineteenth-century aristocrat. He

spent virtually every summer of his life at his fam-

ily’s ancestral estate, Yasnaya Polyana, located

about 130 miles (200 kilometers) south of Moscow.

Although he initially flunked entrance exams

in history and geography, Tolstoy entered Kazan

University in 1844. He was dismissed from the de-

partment of Oriental languages after failing his first

TOLSTOY, ALEXEI KONSTANTINOVICH

1556

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

semester’s final examinations. He reentered the next

year to pursue a law degree, and, two years later,

knowing that he was about to be dismissed once

again, he requested leave for reasons of spoiled

health and domestic circumstances. Tolstoy re-

turned to Yasnaya Polyana with grandiose plans

for self-improvement, experiments in estate man-

agement, and philanthropic projects. Over the next

few years, he made little headway on these plans,

but he did manage to acquire large gambling debts,

a bad reputation, and several bouts of venereal dis-

ease. He also began keeping a detailed diary that,

with some significant lapses, he kept for his entire

life. These journal entries occupy twelve volumes,

each several hundred pages long, of his Complete

Collected Works.

EARLY LITERARY WORKS AND

YASNAYA POLYANA SCHOOL

Tolstoy’s first published work, Childhood (1852),

appeared in the influential journal The Contemporary,

and was signed simply “L.N.” The work was en-

thusiastically praised for the complex psychological

analysis and description conveyed by the work’s

seemingly simple style and episodic, nearly plotless,

structure. The five years after the publication of

Childhood saw Tolstoy’s literary star rise: he pub-

lished sequels to Childhood (Boyhood [1852–1864]

and Youth [1857]) and a handful of war stories. (Tol-

stoy had enlisted as an artillery cadet in 1852 and

seen action in the Caucasus and later in the Russo-

Turkish war). Almost without exception, the stories

enjoyed success with both critics and readers.

TOLSTOY, LEO NIKOLAYEVICH

1557

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

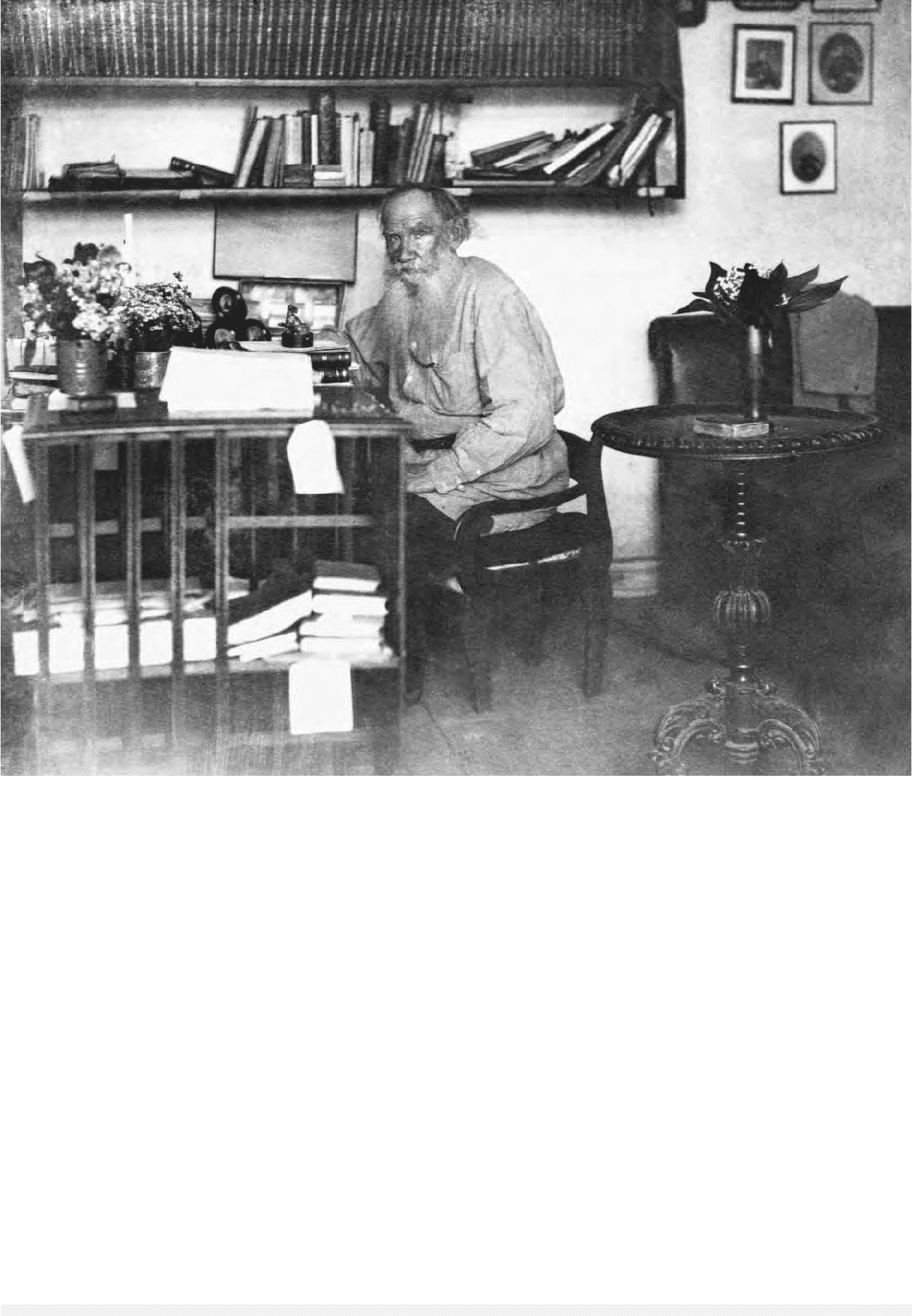

Leo Tolstoy sitting at his desk in Yasnaya Polyana in 1908. © CORBIS

In 1857 Tolstoy left the army as a decorated

veteran and traveled Europe, where he wrote a run

of poorly received stories and novellas that were

praised for their artistry but sharply criticized for

their plainspoken condemnation of civilization and

apathy toward the burning questions of the day.

In part because of this criticism Tolstoy announced

in 1859 his renunciation of literary activity, de-

clared himself forevermore dedicated to educating

the masses of Russia, and founded a school for

peasant boys at Yasnaya Polyana, which he di-

rected until its closure in 1863. Tolstoy produced

few literary works during this time, though he

wrote several articles on pedagogy in the journal

Yasnaya Polyana, which he published privately.

This was not the last time Tolstoy was involved in

education. A decade after closing the second Yas-

naya Polyana school he began an educational se-

ries The New Russian Primer for Reading, and spent

nearly two decades working on it. The primer sold

more than a million copies, making it the most read

and most profitable of Tolstoy’s works during his

lifetime.

MARRIAGE AND THE GREAT

NOVELS (1862–1877)

In the fall of 1862 Tolstoy married Sofya An-

dreevna Behrs, the daughter of a former playmate

and a girl half his age. Their marriage of nearly

fifty years produced ten offspring who survived

childhood and several who did not. Though tu-

multuous, their early relationship was mostly

happy. In 1863 Tolstoy closed his school and com-

menced work on his magnum opus, War and Peace

(1863–1869). Partly a historical account of the pe-

riod from 1805 to 1812, partly a novelistic de-

scription of quotidian life of fictional characters,

and partly a historiographical animadversion on

conventional historical accounts, War and Peace

was initially perceived as defying generic conven-

tion, sharing characteristics with the didactic es-

say, history, epic, and novel. Perhaps reflecting its

chaotic structure, War and Peace portrays war as

intensely chaotic. It ridicules the tsar’s and military

strategists’ self-aggrandizing claims that they were

responsible for the Russians’ victory over la Grande

Armée. The sole effective commander was General

Mikhail Kutuzov, who in previous historical ac-

counts had been portrayed as an inept blunderer.

In the novel he is depicted as the ideal commander

inasmuch as his modus operandi derives from the

maxim “patience and time”—that is, he relies little

on plans and military science, and instead on a

mix of instincts and resignation to fate. The true

heroes of the war, the novel contends, were instead

individual Russians—soldiers, peasants, nobles,

townspeople—who reacted instinctively and un-

consciously, yet successfully, to an invasion of

their homeland.

In 1873 Tolstoy began his second great novel,

Anna Karenina (1873–1878), which has one of the

most famous first lines in world literature: “All

happy families resemble one another, each un-

happy family is unhappy in its own way.” The

novel’s unhappy families are the Karenins, Aleksey

and Anna, and the Oblonskys, Stiva (Anna’s

brother) and Dolly. Anna feels herself trapped in

marriage to her boring if devoted husband, and be-

gins an affair with an attractive if dim officer

named Vronsky. Aleksey denies Anna’s request for

a divorce, and she decides defiantly to live openly

with Vronsky. Their illicit affair is simultaneously

condemned and celebrated by society. Stiva is a

charismatic sybarite who philanders through life

taking advantage of Dolly’s innocence and preoc-

cupation looking after the household. The third,

happy couple of the novel, Konstantin Levin and

Kitty (Dolly’s youngest sister), are unmarried at

the beginning of the story. Their inconstant court-

ship and eventual marriage take place mostly as

the background to the drama of the Oblonskys and

Karenins. The novel ends with Anna, nearly insane

from guilt and stress, throwing herself beneath a

train. Levin, now a family man, undergoes a reli-

gious conversion when he realizes that his constant

preoccupation with questions of life and death,

combined with an innate inclination to philoso-

phize, had prevented his seeing the miraculous sim-

plicity of life itself.

CONVERSION AND LATE WORKS

Notwithstanding his sensual temperament, Tolstoy

had always suffered from sporadic bouts of intense

desire to adopt an ascetic’s life. While still at work

on Anna Karenina, Tolstoy began A Confession

(1875–1884), the first-person narrative of a man—

very similar to Levin at the end of Anna Karenina—

who, despite his success and seeming happiness,

finds himself in the throes of depression and suici-

dal thoughts from which he is rescued by religion.

Although the rhetoric of the work suggests a rad-

ical conversion—Tolstoy later described the time as

an “ardent inner perestroika of my whole outlook

on life”—some critics have cast doubt on the fun-

damentality of the conversion. As early as 1855,

for instance, Tolstoy wrote in his diary plans to

create a new religion “cleansed of faith and mys-

TOLSTOY, LEO NIKOLAYEVICH

1558

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

tery, a practical religion, not promising future bliss,

but giving bliss on earth.”

Tolstoy spent the 1880s and 1890s developing

his religious views in a series of works: A Critique

of Dogmatic Theology (1880), A Translation and Uni-

fication of the Gospels (1881), What I Believe (1884),

and The Kingdom of God Is within You (1893). Most

of these works were banned by the religious or sec-

ular censor in Russia, but were either printed ille-

gally in Russia or printed abroad and clandestinely

smuggled in, thus adumbrating the fate of many

Soviet works printed as samizat or tamizdat. The

core of Tolstoy’s belief is contained in God’s com-

mandments in the Sermon on the Mount: do not

resist evil, swear no oaths, do not lust, bear no mal-

ice, love your enemy. Tolstoy is everywhere and at

pains to point out that adherence to these injunc-

tions, especially nonresistance to evil, inevitably

leads to the abolition of all compulsory legislation,

police, prisons, armies, and, ultimately, to the abo-

lition of the state itself. He described his beliefs as

Christian-anarchism. Vladimir Nabokov described

them as a neutral blend between a kind of Hindu

Nirvana and the New Testament, and indeed Tol-

stoy himself considered his beliefs as a syncretic

reconciliation of Christianity with all the wisdom

of the ages, especially Taoism and Stoicism. Fol-

lowing this creed, Tolstoy became a vegetarian;

gave up smoking, drinking, and hunting; and par-

tially renounced the privileges of his class—for in-

stance, he often wore peasant garb, embraced

physical labor as a necessary part of a moral life,

and refused to take part in social functions that he

deemed corrupt.

His new life led to increased strife with his wife

and family, who did not share Tolstoy’s convic-

tions. It also attracted international attention. Be-

ginning in the 1880s, hundreds of journalists,

wisdom-seekers, and tourists trekked to Yasnaya

Polyana to meet the now-famous Russian writer-

turned-prophet. Tolstoy, who had always kept up

extensive correspondence with friends and family,

was inundated with letters from the curious and

questing. In his lifetime he wrote 10,000 letters and

received 50,000. In 1891 he renounced copyright

over many of his literary works. Free of copyright

restriction and royalties, publishing houses around

the world issued impressive runs of Tolstoy’s

works almost immediately upon their official

publication in Russia. In 1901 his international

fame was increased when Tolstoy was excommu-

nicated for blasphemy from the Russian Orthodox

Church.

In addition to works on philosophy, religion,

and social criticism, Tolstoy penned during the last

decades of his life a number of works of the high-

est literary merit, notably the novella The Death of

Ivan Ilich (1882), the affecting story of a man

forced to admit the meaninglessness of his own

life in the face of impending death; and Hadji Mu-

rat (1896–1904, published posthumously), a

beautifully wrought but uncompleted novel set

during the Russian imperialistic expansion in the

Caucasus. Tolstoy’s third long novel, Resurrection

(1889–1899), though inferior in artistic quality to

his other novels, is a compelling casuistical ac-

count of a man’s attempt to undo the wrongs he

has committed. Tolstoy also wrote an influential

and debated body of art criticism. What Is Art?

(1896–1898) attacked art for not fulfilling its true

mission, namely, the uniting of people into a uni-

versal collective. His On Shakespeare and Drama

(1903–1904) dismissed Shakespeare as a charla-

tan.

Increasingly distressed by domestic conflict and

angst over the incommensurability of his life with

his beliefs, Tolstoy left home in secrecy in the au-

tumn of 1910. His flight was immediately broad-

cast by the international media, which succeeded

in tracking him down to the railway stop Astapovo

(later renamed Leo Tolstoy), where he lay dying of

congestive heart failure brought on by pneumonia.

What could only be described as a media circus was

assembled outside the stationmaster’s house when

Tolstoy died early in the morning of November 7,

1910. His final words were “Truth, I love much.”

See also: ANARCHISM; GOLDEN AGE OF RUSSIAN LITERA-

TURE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Eikhenbaum, Boris. (1972). The Young Tolstoy, tr. Gary

Kern. Ann Arbor, MI: Ardis.

Eikhenbaum, Boris. (1982). Tolstoi in the Sixties, tr.

Duffield White. Ann Arbor, MI: Ardis.

Eikhenbaum, Boris. (1982). Tolstoi in the Seventies, tr. Al-

bert Kaspin. Ann Arbor, MI: Ardis.

Gustafson, Richard F. (1986). Leo Tolstoy: Resident and

Stranger: A Study in Fiction and Theology. Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press.

Morson, G. S. (1987). Hidden in Plain View: Narrative and

Creative Potentials in War and Peace. Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press.

Orwin, Donna Tussing. (1993). Tolstoy’s Art and Thought,

1847–1880. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

TOLSTOY, LEO NIKOLAYEVICH

1559

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Orwin, Donna Tussing, ed. (2002). Cambridge Compan-

ion to Tolstoy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wasiolek, Edward. (1978). Tolstoy’s Major Fiction.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wilson, A. N. (1988). Tolstoy. New York: W. W. Nor-

ton and Company.

M

ICHAEL

A. D

ENNER

TOMSKY, MIKHAIL PAVLOVICH

(1880–1936), Russian union activist.

Tomsky was a leading Old Bolshevik and trade

union activist who committed suicide before he

could be tried during Josef Stalin’s purges. Tom-

sky was born Mikhail Efremov into a working-

class environment. He began to work in a factory

in adolescence and eventually became a printer. He

joined the Social Democrats in 1904 and soon

turned to union organizing. Between 1906 and

1909 his activities led to a series of arrests that was

interspersed with party work whenever he was

free. During this period he adopted the pseudonym

Tomsky. In 1911 he began a five-year term of hard

labor that was followed by exile to Siberia. After

the collapse of the monarchy, Tomsky returned to

Petrograd and his union work. In 1919 he was

elected to the Central Committee and chosen to head

the Central Trade Union Council. Three years later

he became a member of the Politburo. He was one

of the eight pallbearers at Vladimir Lenin’s funeral

in 1924. The next year he sided against Leon Trot-

sky and his followers in the party struggles that

followed Lenin’s death. In 1928 he joined with

Nikolai Bukharin and Alexei Rykov to protest the

pace and methods of collectivization. After this op-

position group was defeated, Tomsky was expelled

from the Politburo and removed from his position

as trade union leader. In 1931 he was appointed

head of the State Publishing House. Tomsky shot

himself after learning that he had been implicated

in one of Stalin’s show trials. At Bukharin’s trial

two years later fabricated evidence named Tomsky

as the link between members of the Right Opposi-

tion and an oppositional group in the Red Army.

See also: BUKHARIN, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH; POLITBURO;

RYKOV, ALEXEI IVANOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sorenson, Jay B. (1969). The Life and Death of Soviet Trade

Unionism, 1917–1928. New York: Atherton Press.

Wynn, Charters. (1996). From the Factory to the Kremlin:

Mikhail Tomsky and the Russian Worker. Washington,

DC: National Council for Soviet and East European

Research.

A

LISON

R

OWLEY

TORKY

The nomadic Torky (known as Torky in Rus and

Oghuz in Eastern sources) spoke a Turkic language

and probably practiced shamanist-Täri religion.

They formed into a tribal confederation in the

eighth century in the Syr Darya–Aral Sea steppe

region. In the late ninth century, joined by the

Khazars, they expelled the Pechenegs from the

Volga-Ural area and forced them to migrate to the

South-Russian steppe. In 965, joined by the Rus,

the Torky destroyed the Khazar state, and in 985

the two allies attacked Volga Bulgharia. The mi-

gration of the Polovtsy, Torky’s eastern neighbors,

forced the latter into the South-Russian steppe by

1054 or 1055. In 1060, the Rus staged a major of-

fensive and scored a victory over the Torky. While

many Torky fled west, some remained in the

South-Russian steppe zone and joined other no-

madic peoples to later develop into Rus border

guards known as Chernye Klobuky or Black Hoods.

From around 1060 to 1140, Chernye Klobuky re-

mained outside the formal political boundaries of

the Rus state and maintained a largely nomadic

lifestyle. During this period, they were often in-

volved in the military affairs of the Rus princes and,

at times, came to settle within the Rus borders in

return for their services. After 1140 the institution

of Chernye Klobuky became formalized, and they

came to be viewed as mercenaries and vassals of

the Kievan Grand Princes. As vassals, the Chernye

Klobuky maintained allegiance not to any particu-

lar branch of the royal Rus family, but to the holder

of the title of Grand Prince of Kiev.

See also: KHAZARS; KIEVAN RUS; POLOVTSY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Golden, Peter B. (1990). “The Peoples of the South Rus-

sian Steppe.” In The Cambridge History of Early Inner

Asia, ed. Denis Sinor. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Golden, Peter B. (1992). An Introduction to the History of

the Turkic Peoples. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

TOMSKY, MIKHAIL PAVLOVICH

1560

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Golden, Peter B. (1996). “Chernii Klobouci.” In Symbolae

Turcologicae: Studies in Honour of Lars Johanson on his

Sixtieth Birthday, 8 March 1996, eds. Á. Berta; B.

Brendemoen; and C. Schönig (Transactions /

Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul, v. 6). Stock-

holm: Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul.

R

OMAN

K. K

OVALEV

TOTALITARIANISM

The concept of totalitarianism was used to describe

the more extreme forms of the hypertrophic states

of the twentieth century, with their ideologies,

elaborate mechanisms of control, and uniquely in-

vasive efforts to diminish or even obliterate the dis-

tinction between public and private. The term was

coined in the early 1920s, in Fascist Italy, by Mus-

solini’s opponents and was expanded in the early

1930s to include National Socialist Germany. Al-

though the term was coined by opponents of Fas-

cism and early usages were largely hostile, it was

also episodically employed by supporters of the

Italian and German regimes, such as Giovanni Gen-

tile and Mussolini himself, to differentiate their

governments from the allegedly decadent liberal

regimes they so detested. The very early Italian us-

ages connoted extreme violence, but as Italian Fas-

cism evolved from its movement phase and became

an ideology of government, the term increasingly

suggested the intent of the state to absorb every

aspect of human life into itself. This notion was in

harmony with the philosophy of Giovanni Gentile.

The term was most systematically and positively

used in Germany by Carl Schmitt, but Hitler even-

tually forbade its positive use, since it evoked an

Italian comparison, which he disliked.

Even in the 1920s and early 1930s, there were

a number of people who suggested that the Soviet

Union bore certain similarities to both Italy and

Germany. After Hitler’s blood purge in 1934, the

similarities between the Soviet Union, Germany,

and Italy became the subject of frequent and sys-

tematic comparison; after the Molotov-Ribbentrop

Pact (1939), such comparisons became widespread.

Only in strongly pro-communist circles was there

an understandable reluctance to conclude that the

Soviet Union had degenerated so badly that it could

be compared with Nazi Germany.

In the aftermath of World War II, however,

this comparison came to dominate the term’s us-

age, right up to the end of the Cold War. The Tru-

man administration suddenly began discussing the

Soviet Union as a totalitarian regime when it had

to justify the strongly anti-Soviet turn in Ameri-

can foreign policy that began in 1947, expressed

most vividly in the Truman Doctrine and the Mar-

shall Plan.

Prewar usages in the 1920s and 1930s had been

unsystematic and largely journalistic, though such

dedicated students of Russia as William Henry

Chamberlin had compared the Soviet Union and

Germany more systematically as early as 1935. But

World War II and the development of the Cold War

created a community of Russian experts in acade-

mia, where the term became thoroughly institu-

tionalized in the early 1950s. The first systematic

and grand-scale comparison, however, was not by

an American academic, but by a German-Jewish

émigré, Hannah Arendt, whose brilliant but uneven

Origins of Totalitarianism was a sensation when it

appeared in 1951. The most influential academic

treatment of the term was Totalitarian Dictatorship

and Autocracy by Carl Friedrich and Zbigniew

Brzezinski, which appeared in 1956 and had a long

and controversial life. Brzezinski and Friedrich’s

account provided what was variously called a syn-

drome and a model to classify states as totalitarian.

To be accounted, a state had to exhibit six features:

an all-encompassing ideology; a single mass party,

typically led by one man; a system of terror; a near-

monopoly on all means of mass communication; a

similar near-monopoly of instruments of force; and

a centrally controlled economy.

Although Totalitarian Dictatorship and Autoc-

racy achieved wide acceptance in the 1950s, the re-

stricted nature of its comparison, as well as the

changing political times, made it highly contro-

versial in the following two decades, with most of

the academic community turning against it. Its fate

was intimately bound up with the Cold War, which

lost its broad base of popular support among West-

ern academics and intellectuals during the 1960s.

The viability of a term as value-laden as totalitar-

ianism, in light of the demand for analytical rigor

in the social sciences, was now considered highly

debatable. In addition, as American historians of

Russia became more and more enamored of social

history, the focus of the totalitarian point of view

on the politics of the center seemed far too restric-

tive for their research agenda, which was more fo-

cused on the experiences of ordinary people and

everyday life, especially in the provinces.

TOTALITARIANISM

1561

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

During the Reagan years, the term was revived

by neoconservatives interested in a more aggressive

political and military challenge to the Soviet Union

and also in distinguishing the Soviet Union and its

satellites from the (allegedly less radical) rightist

states whom the Reagan administration regarded

as allies against Communism. With the collapse of

the Soviet Union, however, the term has become

less politically charged and seems to be evolving in

a more diffuse fashion to suggest closed or antide-

mocratic states in general, particularly those with

strong ideological or religious coloration.

See also: AUTOCRACY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arendt, Hannah. (1973). The Origins of Totalitarianism.

New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

Friedrich, Carl J., and Brzezinski, Zbigniew. (1965). To-

talitarian Dictatorship and Autocracy. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Gleason, Abbott. (1995). Totalitarianism: The Inner His-

tory of the Cold War. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Halberstam, Michael. (2000). Totalitarianism and the

Modern Concept of Politics. New Haven, CT: Yale Uni-

versity Press.

Havel, Vaclav. (1985). “The Power of the Powerless.” In

The Power of the Powerless: Citizens Against the State

in Central-Eastern Europe, ed. John Keane. Armonk,

NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Lifka, Thomas E. (1988). The Concept “Totalitarianism”

and American Foreign Policy, 1933–1949. New York:

Garland.

Orwell, George. (1949). 1984. New York: New Ameri-

can Library.

A

BBOTT

G

LEASON

TOURISM

Though tourism was not a product of the Russian

Revolution, the Bolshevik emphasis on raising the

cultural level of the masses and educating through

practical experience made tourism one of the con-

cerns of the new regime. The government created

a number of institutions to encourage development

in this field. Within Narkompros and Glavprolit-

prosvet, excursion sectors were established as early

as 1919 to organize educational trips throughout

the country; a number of these bureaus later de-

veloped into scientific-research bodies such as the

Central Museum-Excursion Institute in Moscow.

The two major organizations for Soviet tourism—

the Society for Proletarian Tourism (OPT RFSFR,

created by decree of the People’s Commissariat for

Internal Affairs) and the joint-stock society Soviet

Tourist (created by Narkompros in 1928)—merged

in 1930 under the name of the All-Union Society

of Proletarian Tourism and Excursions (OPTE) un-

der the direction of N. V. Krylenko. It was also at

this time that mass tourism began to develop as a

movement among Soviet youth, marked by the es-

tablishment of a separate bureau within the Kom-

somol in 1928. Students, pioneers, and other

young Soviets went on tours of the country orga-

nized under themes such as “My Motherland—the

USSR.” Excursions were designed to acquaint citi-

zens with national monuments, the history of the

revolutionary movement, and the life of Vladimir

Lenin. This so-called sphere of proletarian tourism

was thus intended as an integral aspect of the con-

struction of socialism within the Soviet Union.

The importance of travel was not limited, how-

ever, to shaping Soviet ideology within the coun-

try. The state recognized that foreigners visiting the

Soviet Union also represented a significant means

through which socialism might gain expression

and adherents throughout the world; additional

consideration was given to the inflow of capital

from international tourists. Though certain privi-

leged groups of udarniki, fine arts performers, mu-

sicians, students, and government officials traveled

beyond Soviet borders in the country’s initial years,

millions of visitors ultimately toured the Soviet

Union throughout its roughly seventy-year his-

tory.

To aid in the maintenance of foreign tours and

international travel to the Soviet Union, on April

12, 1929, the Council for the Labor and Defense of

the USSR adopted the decree “On the organization

of the All-Union Joint-Stock Company for Foreign

Tourism in the USSR.” Otherwise known as In-

tourist (an acronym of Gosudarstvennoe aksion-

ernoe obshchestvo po innostrannomu turizmu v

SSSR and an abbreviated form of Inostrannyi tur-

ist), the company was supported by a number of

Soviet organizations such as the People’s Commis-

sariat of Trade, Sovtorgflot, the People’s Commis-

sariat of Rail Transport, and the All-Union

Joint-Stock Company Otel’. A. S. Svanidze was

its first chairman. Though Intourist was occasion-

ally responsible for organizing the visits of more

TOURISM

1562

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY