Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

TUGAN-BARANOVSKY, MIKHAIL

IVANOVICH

(1865–1919), political economist and social theorist.

The most significant prerevolutionary Russian

and Ukrainian contributor to economics, Tugan-

Baranovsky was born near Kharkov, Ukraine, and

attended Kharkov University. As a leading member

of the Legal Marxist group, Tugan attempted to re-

form orthodox Russian Marxism by adding a large

dose of neo-Kantian ethics, together with insights

from British classical economics and a dash of the

German historical school. In economic theory Tu-

gan’s most significant work was Industrial Crises

in Contemporary England (1894). This pioneered the

detailed empirical description of trade cycles—to-

gether with concern for their social consequences—

alongside a theoretical explanation combining

maldistribution of income, disproportion between

industrial branches, and a mechanistic steam en-

gine analogy using free loanable capital as the mo-

tor force. This approach influenced Western

macroeconomic theorists such as John Maynard

Keynes, Dennis Robertson, and Michal Kalecki.

Tugan also wrote a major work examining the

history of the Russian factory using legislative and

business history sources, a widely read account of

the principles of political economy, and a study of

cooperative institutions. In addition, Tugan made no-

table contributions to social theory, monetary eco-

nomics, conceptions of socialist planning, and the

history of economics. Towards the end of his life Tu-

gan’s allegiance shifted from Russia back to Ukraine,

and he was Ukrainian Minister of Finance from Au-

gust to December 1917. During 1918 he helped to

establish the Academy of Science in Kiev, and died on

a train headed for Paris the following year.

See also: INDUSTRIALIZATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barnett, Vincent. (2001). “Tugan-Baranovsky as a Pio-

neer of Trade Cycle Analysis.” Journal of the History

of Economic Thought 23(4):443–466.

Crisp, Olga. (1968). “M.I. Tugan-Baranovskii.” In Inter-

national Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, ed. D. L.

Sills, vol. 16. New York: Macmillan.

Tugan-Baranovsky, M. I. (1970). The Russian Factory in

the Nineteenth Century, tr. Arthur Levin and Cleora

S. Levin. Homewood, IL: R. D. Irwin for the Amer-

ican Economic Association.

V

INCENT

B

ARNETT

TUKHACHEVSKY, MIKHAIL

NIKOLAYEVICH

(1893–1937), prominent Soviet military figure;

strategist, commander, weapons procurer.

Mikhail Tukhachevsky is one of the most im-

portant and controversial figures in the history of

the Soviet armed forces. Born into aristocracy, he

attended prestigious imperial military schools and

academies before joining the communist cause and

becoming a fervent Bolshevik. He served in World

War I and was taken prisoner by the Germans. He

escaped, and later commanded Red Army troops in

the civil war. Tukhachevsky held numerous im-

portant posts within the Red Army, including chief

of the Red Army Staff, Chief of Armaments, and

Commander of the Leningrad Military District. In

1935 he was awarded the highest military honor

of Marshal of the Soviet Union.

Tukhachevsky was an innovative and shrewd

military strategist who theorized combat scenarios

for future wars, created new means of employing

forces, and worked tirelessly for the implementa-

tion of his ideas into the rearmament and reform

of the armed forces. He incessantly called for more

resources to be devoted to rearmament, in spite of

numerous competing demands on limited resources

from other state sectors.

Tukhachevsky wrote many articles about mil-

itary tactics and strategy, the most important of

which was Future War (1928). This 700-page trea-

tise surveyed the combat potential of all countries

neighboring the USSR, offering a range of combat

scenarios in the event of war. Together with his

military colleagues, Tukhachevsky developed the

tactical force employment concept of deep battle.

This maneuver involved the use of tanks and air-

craft to penetrate deep into the enemy’s defense and

destroy his forces. The deep battle concept was in-

corporated into Soviet 1936 Field Regulations and

was utilized in the Red Army’s combat operations

against the German Army in the second half of

World War II. The deep battle concept also found

expression in NATO military doctrine in the 1980s.

Tukhachevsky’s contributions arguably rendered

him the most prescient and talented strategist in

the Red Army in the 1920s and 1930s.

While commander of troops in the Leningrad

Military District, Tukhachevsky worked closely

with designers and theorists to develop a variety of

new weapons and methods for employing them.

In addition, he mastered the technical details of

TUKHACHEVSKY, MIKHAIL NIKOLAYEVICH

1583

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

complex weapons systems, from aircraft engines

to dirigibles and rocket propulsion systems.

Tukhachevsky also oversaw aspects of the secret

military collaboration with German aircraft and

chemical weapons experts, urging the Germans to

share more of their knowledge and experience than

they were sometimes willing. When tensions de-

veloped in Manchuria in 1931, presenting the

threat of war to the Soviet Union from East and

West, defense production became a higher priority,

and many of Tukhachevsky’s projects came to

fruition.

Tukhachevsky’s relationship with Josef Stalin,

who ordered his execution in 1937 during the Great

Terror, is controversial and unresolved. The origins

of the tension between Stalin and Tukhachevsky

have been traced to several events, documents, and

rumors. Possible factors include: conflicts between

Stalin and Tukhachevsky over the command of the

Battle for Warsaw in 1920; Tukhachevsky’s criti-

cism of the role of the cavalry army in the civil

war for which Stalin served as chief political com-

missar; Tukhachevsky’s warnings of the German

military threat to the USSR; and documents falsi-

fied by Germans or Czechoslovak agents alleging

Tukhachevsky’s intent to overthrow the Soviet

leadership together with Nazi forces.

See also: MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET; PURGES,

THE GREAT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexandrov, Victor. (1963). The Tukhachevsky Affair.

London: MacDonald.

Samuelson, Lennart. (1999). Plans for Stalin’s War Ma-

chine: Tukhachevskii and Military-Economic Planning.

New York: St. Martin’s.

Stoecker, Sally. (1998). Forging Stalin’s Army: Marshal

Tukhachevsky and the Politics of Military Innovation.

Boulder, CO: Westview.

S

ALLY

W. S

TOECKER

TUPOLEV, ANDREI NIKOLAYEVICH

(1888–1972), patriarch of Soviet aircraft design.

Andrei Tupolev was one of the most important

aircraft designers in the Soviet Union during the

interwar period and was awarded the honor of

“Hero of Socialist Labor” three times in his career.

Tupolev is considered by many to be the father of

Soviet nonferrous metal aircraft construction, and

he developed more than fifty original aircraft de-

signs and over 100 modifications. In addition to

fighter aircraft and heavy long-range bomber air-

craft, Tupolev also designed aero-sleighs, dirigibles,

and torpedo boats. Educated at the prestigious Bau-

man Technical School in Moscow, he was one of

the founders of the Central Aviation Institute in

1918 and created a design bureau within it. He

spent most of his career at the design bureau and

in 1936 received orders from the Heavy Industry

Commissariat to transfer to GUAP (State Direc-

torate of Aviation Industry) as their chief engineer

who oversaw aircraft production. In May 1937,

Tupolev’s ANT-7 flew to the North Pole success-

fully. One month later, he was accused of being an

enemy of the state and was arrested for his alleged

role in espionage. After serving one year in regu-

lar prison, Tupolev was permitted to continue his

design work in a special prison as a means of avoid-

ing hard labor. Although his name was temporar-

ily withdrawn from public, his stature was

restored in the post-Stalin era.

See also: AVIATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Saukke, M. B. (1993). The Little-Known Tupolev (Neizvest-

nyi Tupolev). Moscow: Original.

Yakovlev, A.S. (1982). Soviet Aircraft (Sovetskiye samo-

lety). Moscow: Nauka.

S

ALLY

W. S

TOECKER

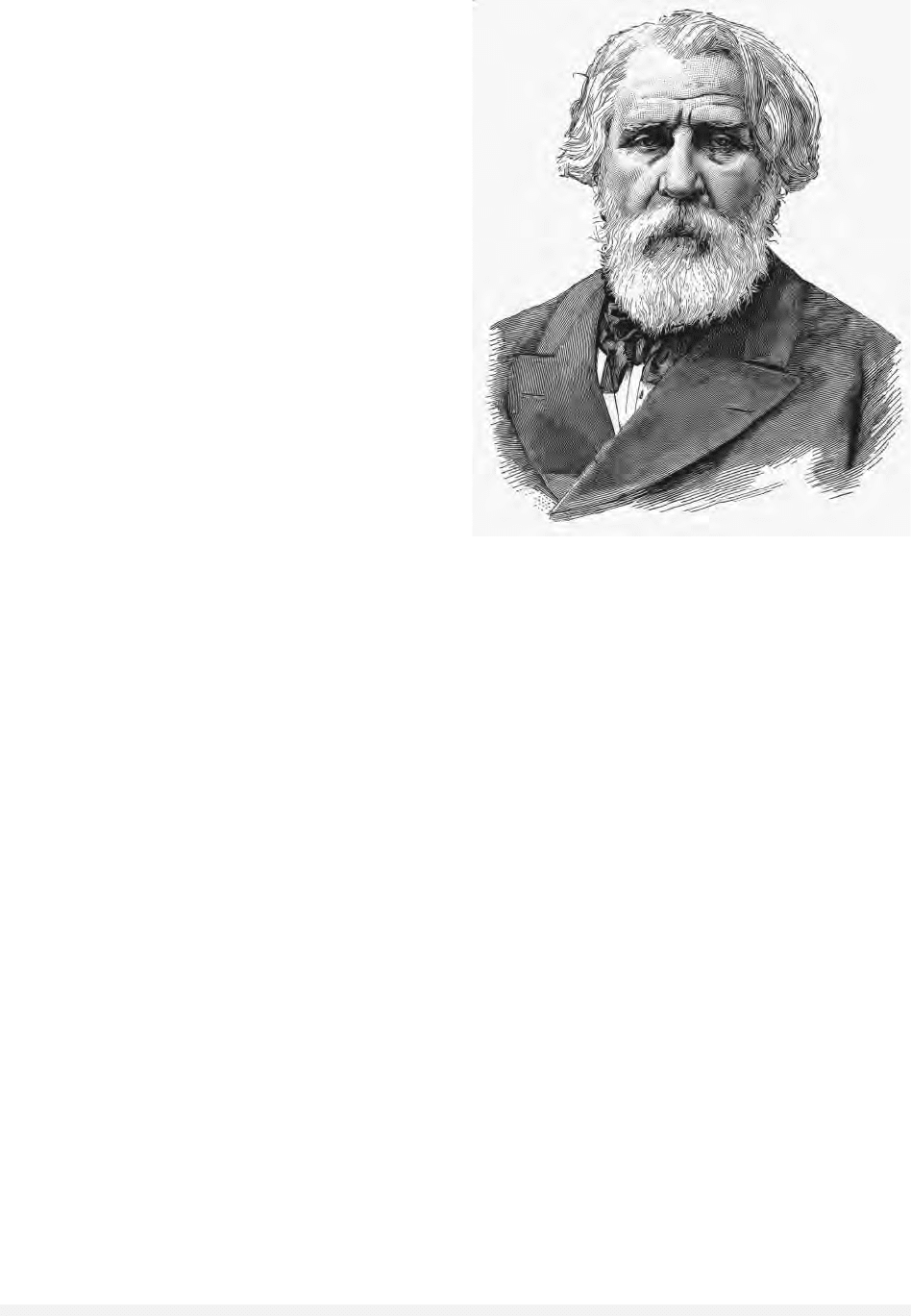

TURGENEV, IVAN SERGEYEVICH

(1818–1883), Russian novelist, playwright, and

poet.

Turgenev was born into an extremely wealthy

family on an estate with 500 serfs near Oryol, in

the Mtsensky uezd, in central European Russia. His

mother, a tyrannical shrew, savagely beat her serfs

and her sons and despised all things Russian. The

family spoke only French in the home. His father

was an attractive and dissipated rake. Turgenev’s

childhood nurtured in him an animosity toward

the institution of serfdom and a profound under-

standing of the culture of rural, aristocratic culture

of pre-Reform Russia—the very cultural wellspring

from which so many of the characters in his nov-

els were to emerge.

TUPOLEV, ANDREI NIKOLAYEVICH

1584

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Turgenev is nearly universally mentioned, along

with Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Leo Tolstoy, as one

of the great masters of the psychological novel, al-

though Turgenev himself disparaged more than

once the emphasis on psychological analysis that

marks the works of the other two members of that

triumvirate. Turgenev further distinguished him-

self from Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky by beginning

his career as a poet: his first major work was the

long poem Parasha, published in 1843—a year be-

fore Dostoyevsky’s entrée into literature and nearly

a decade before Tolstoy’s. Parasha was followed by

a handful of other significant verse works, though

Turgenev later wrote that he felt a nearly physical

antipathy toward his verse works.

Although his poetry was enthusiastically re-

ceived by Vissarion Belinsky, the leading literary

critic of the time, Turgenev’s first work of lasting

influence was a series of sketches of what Turgenev

knew first-hand from his childhood: the manorial,

rural, and peasant milieus. The brief, episodic de-

scriptions were initially published separately, be-

ginning in 1847, and then as a single work, A

Huntsman’s Sketches, in 1852. The work exercised

a profound influence on the public that is often

likened to that of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle

Tom’s Cabin, published the same year. Turgenev’s

work is one of the highest artistic quality—ex-

quisite, tightly crafted descriptions of the physical

world combined with engaging and complex por-

traits of peasants (generally positively portrayed)

and gentry (generally negatively portrayed).

Beginning soon after the death of Nicholas I in

1855, Turgenev, always sensitive to the winds of

change, wrote his four most significant novels:

Rudin (1856), Home of the Gentry (sometimes trans-

lated, more literally, as Nest of Gentlefolk) (1859),

On the Eve (1860) and Fathers and Sons (more pre-

cisely Fathers and Children) (1862). All are pene-

trating chronicles of the quickly shifting alliances,

mores, and institutions that marked the initiatory

period of the Great Reforms, with all its optimism

and surety of a brighter future. The greatest of

these, Fathers and Sons, depicts the intergenerational

conflict between the liberal men of the 1840s, with

their refined, European (more specifically, Gallic)

sensibilities and an inclination toward incremen-

talism in social and political change; and the new

people of the younger generation, nihilists (a word

Turgenev brought into coinage), men of science

who embraced German-inflected positivism, dis-

paraged aesthetics per se, and believed in the cre-

ative potential of destruction. The older generation

found Turgenev’s portrait of their brethren dis-

missive and patronizing, and the younger generation

found their reflection insulting and patronizing.

Turgenev, criticized from nearly every political an-

gle, responded by quitting Russia for Western Eu-

rope. From his refuge in Baden-Baden, Turgenev

wrote Smoke (1867), a venomous satire that at-

tacked, inter alia, the radicalized intelligentsia in

exile, the Europeanized Russian aristocracy, and the

conservative Slavophiles.

Poems in Prose, Turgenev’s final work, sealed his

reputation as the first Russian stylist. The final

poem famously praises the Russian language as

great, powerful, truthful, and free, a tribute per-

haps nowhere truer than when the Russian words

flowed from Turgenev’s own pen. He died near

Paris in 1882, and, according to his wishes, his

body was transported back to St. Petersburg where

it was interred in perhaps the largest public funeral

in Russian history.

See also: DOSTOYEVSKY, FYODOR MIKHAILOVICH; GOLDEN

AGE OF RUSSIAN LITERATURE; TOLSTOY, LEO NIKO-

LAYEVICH

TURGENEV, IVAN SERGEYEVICH

1585

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Ivan Turgenev, engraving from a French publication of 1881.

T

HE

A

RT

A

RCHIVE

/M

USÉE

C

ARNAVALET

P

ARIS

/D

AGLI

O

RTI

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, Elizabeth Cheresh. (1992). Beyond Realism: Tur-

genev’s Poetics of Secular Salvation. Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press.

Costlow, Jane T. (1990). Worlds within Worlds: The Nov-

els of Ivan Turgenev. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Uni-

versity Press.

Magarshack, David. (1954). Turgenev: A Life. New York:

Grove Press.

Schapiro, Leonard Bertram. (1978). Turgenev, His Life and

Times. New York: Random House.

Seeley, Frank Friedeberg. (1991). Turgenev: A Reading of

His Fiction. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge

University Press.

M

ICHAEL

A. D

ENNER

TURKESTAN

Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan,

and southern Kazakhstan cover the territory of for-

mer Turkestan. The region is mostly desert and

semi-desert, with the exceptions of the mountain-

ous east and the river valleys. The major rivers are

the Amu Darya, Zeravshan, Syr Darya, Chu, and

Ili. Of the five major ethnic groups, most Turkmen,

Kyrgyz, and Kazakhs were still nomads in 1900,

but most Uzbeks had taken up agriculture or ur-

ban life, the traditional pursuits of the Tajiks.

Russia was drawn into Turkestan by the need

for a stable frontier and the desire to forestall British

influence. The Turkestan oblast was formed in

1865, subject to the Orenburg governor-general,

from territories recently conquered from the

Kokand khanate. These included Tashkent, one of

the two largest towns in the region (the other was

Bukhara). In 1867 the Turkestan government-gen-

eral was established, consisting of two oblasts—Syr

Darya and Semireche—responsible directly to the

war minister, with Tashkent as its capital.

Further annexations from the Uzbeg khanates

expanded the government-general. Bukhara’s de-

feat in 1868 added the Zeravshan okrug, including

Samarkand. The right bank of the lower Amu

Darya was annexed to the Syr Darya oblast as a

result of Khiva’s defeat in 1873, and the remain-

der of Kokand was annexed as the Fergana oblast

in 1876. In 1882 Semireche was transferred to the

new Steppe government-general, reducing Turkestan

to two oblasts, but four years later the Zeravshan

okrug, enlarged at the expense of Syr Darya, was

renamed the Samarkand oblast. In 1898 Semireche

was returned to the Turkestan government-general

and the Transcaspian oblast was added to Tashkent’s

jurisdiction.

Turkestan’s value to Russia was primarily

strategic until the late 1880s. In the wake of the

construction of the Central Asian Railroad, con-

necting the Caspian seacoast with Samarkand in

1888 (extended to Tashkent in 1898), the govern-

ment-general’s importance as a source of cotton

grew rapidly. It supplied almost half of Russia’s

needs by 1911. The opening of the Orenburg-

Tashkent railroad in 1906 facilitated imports of

grain to deficit areas like Fergana, where 36 to 38

percent of the sown area was given over to cotton

by World War I. To the same end the construction

of a line from Tashkent to western Siberia was be-

gun before the war. Cotton fiber and cottonseed

processing were the major industries.

As of the 1897 census, Turkestan’s five oblasts

contained 5,260,300 inhabitants, 13.9 percent of

them urban. The largest towns were Tashkent

(156,400), Kokand (82,100), Namangan (61,900),

and Samarkand (54,900). By 1911, 17 percent of

Semireche’s population and half of its urban resi-

dents were Russians, four-fifths of them agricul-

tural colonists. In the other four oblasts in the same

year, Russians constituted only 4 percent of the

population, and the overwhelming majority lived

in European-style settlements alongside the native

quarters in the major towns.

The Soviet government reorganized the gov-

ernment-general in 1918 as the Turkestan ASSR of

the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic. In

1924 the Turkestan republic was abolished. Its

northern districts, inhabited by Kazakhs, were in-

corporated in the Kazakh ASSR of the Russian re-

public; its eastern districts, inhabited by Kyrgyz,

were joined to the Kazakh republic as the Kyrgyz

Autonomous Oblast. The remainder of Turkestan

was divided into the Turkmen and Uzbek Soviet

Socialist Republics, the latter’s southeast forming

the Tajik ASSR.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Becker, Seymour. (1988). “Russia’s Central Asian Em-

pire, 1885–1917.” In Russian Colonial Expansion to

1917, ed. Michael Rywkin. London: Mansell Pub-

lishing.

TURKESTAN

1586

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Pierce, Richard A. (1960). Russian Central Asia, 1867–1917:

A Study in Colonial Rule. Berkeley: University of Cal-

ifornia Press.

S

EYMOUR

B

ECKER

TURKEY, RELATIONS WITH

Through most of the 500 years preceding the col-

lapse of the Soviet Union, Russia and Turkey were

enemies. Initially it was an expanding Ottoman

Empire that conquered traditionally Russian lands,

but then as the Ottoman Empire weakened, it was

tsarist Russia’s turn to expand at the expense of

the Ottomans. Highlighting Russian expansion was

the Treaty of Kuchuk Karnadji in 1774, which not

only gave Russia the Crimea, but also the right to

intervene in the Ottoman Empire to protect ortho-

dox believers. Then, in the nineteenth century, it

was Russian military pressure, in cooperation with

Britain and France, that helped free Greece from Ot-

toman control in 1827. While the Russian drive

against the Ottoman Empire and Moscow’s efforts

to control the Turkish Straits failed during the

Crimean War (1853–1853), twenty years later (in

1876–1877) Russia helped free the Bulgarians from

Ottoman control in a war against the Ottoman Em-

pire. During World War I, Russia and the Ottoman

Empire were on opposite sides, with Russia’s ally

Britain promising the straits to Moscow to help

keep it in the war.

Following World War I, when the communists

seized control of Russia and Kemal Attaturk took

power in Turkey, there was a brief warming of

relations as Moscow supplied weapons to help

Turkey drive out the armies of their common en-

emies, France and Britain. During World War II,

Turkey was ostensibly neutral but appeared sym-

pathetic to the Germans, and at the end of the war

Stalin demanded bases in the Turkish Straits and

Turkish territory in Transcaucasia. Stalin, how-

ever, was unable to implement Russian demands

because of U.S. support for Turkey. At the same

time, however, by solidifying its control over the

Eastern Balkans, Moscow posed a threat to Turkey

on its border with Bulgaria.

Throughout the early stages of the Cold War,

Turkey was a loyal member of the North Atlantic

Treaty Organization (NATO), sending troops to

help the United States in the Korean War–much to

the anger of Moscow. Relations between Moscow

and Ankara, however, began to warm in the 1970s

(in part because of the U.S.-Turkish conflict over

Cyprus) and in the 1980s the two countries nego-

tiated an important natural gas agreement. Still, at

the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union, rela-

tions could be seen as correct if not particularly

friendly.

RELATIONS SINCE THE COLLAPSE OF

THE USSR

Since the end of 1991, when the Soviet Union was

dissolved, Turkish-Russian relations have gone

through three stages. The first period, 1991 to

1995, saw a mixture of economic cooperation and

geopolitical confrontation; the second period, 1996

to 1998, witnessed an escalation of the geopoliti-

cal confrontation, and the third period, 1998 to

2003, following the economic crisis in Russia in

August through September 1998, saw the rela-

tionship transformed into a far more friendly and

cooperative one.

In the first period trade was the primary fac-

tor fostering the relationship. By the time of the

Russian economic crisis of 1998, trade had risen to

$10 billion per year, making Turkey Russia’s pri-

mary Middle East trading partner and at the same

time creating a strong pro-Russian business lobby

in Turkey, composed of such companies as Enka,

Gama, and Tekfen. Indeed, Turkish companies even

got the contract to rebuild the Russian Duma, dam-

aged in the 1993 fighting, and Turkish merchants

donated $5 million to Yeltsin’s 1996 reelection

campaign. Moscow also sold military equipment to

Turkey, including helicopters (prohibited for sale to

Turkey by NATO) that the Turks could use to sup-

press the Kurdish uprising in Southeast Turkey.

If economic and military cooperation was evi-

dent during this period, so was competition. With

the collapse of the USSR, Moscow feared Turkish

inroads into Central Asia and Transcaucasia seen

by the Russian leadership as the soft underbelly of

the Russian Federation. Reinforcing this concern

were Turkish efforts to promote the Baku-Tbilisi-

Ceyhan oil pipeline route for Caspian Sea oil that

would rival Moscow’s Baku-Novorossisk route.

For its part, Turkey complained about the Russian

military buildup in Armenia and Georgia, about the

ecological dangers posed by Russian oil tankers

going through the straits, and about Russian aid

to the Kurdish rebels. On the other hand, once the

first Chechen war had erupted in December 1994,

TURKEY, RELATIONS WITH

1587

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Moscow complained about Turkish aid to the

Chechen rebels.

Relations between Turkey and Russia sharply

deteriorated in 1996 after Yevgeny Primakov be-

came Russia’s foreign minister. Primakov sought

to create a pro-Russian grouping of states such as

Greece, Armenia, Syria, and Iran to outflank Turkey.

Furthermore, he supported the sale in January

1997 of a very sophisticated SAM 300-PMU-1

surface-to-air missile system to the Greek portion

of Cyprus, something that, if deployed, would

threaten the airspace of a large part of southern

Turkey. Turkey took the proposed SAM-300 sale

seriously and threatened to destroy the missiles if

they were deployed. Finally, Moscow stepped up

its diplomatic support for the Kurdish rebellion, al-

lowing Kurdish conferences to be held in Moscow.

The only bright spot in Turkish-Russian rela-

tions during this period came in December 1997

when then Russian prime minister Viktor Cher-

nomyrdin came to Ankara to sign the Blue Stream

natural gas agreement, which would increase the

amount of natural gas Turkey would import from

Russia from 3 billion cubic meters per year in 2000

to 30 billion cubic meters per year in 2010, with

16 billion cubic meters coming from the Blue

Stream pipeline under the Black Sea and 14 billion

cubic meters coming from enlarged pipelines

through the Balkans.

Following the Russian economic crisis of Au-

gust-September 1998, confrontation gave way to

cooperation in the Russian-Turkish relationship.

This was due to a number of causes. First, Pri-

makov’s efforts to build an alignment of Iran, Ar-

menia, Syria, and Greece against Turkey fell apart

as Greece and Turkey had a major rapprochement.

Second, the economic crisis weakened Russia so that

Primakov, who had become prime minister in Sep-

tember 1998, realized that Russia simply did not

have the economic resources to implement the mul-

tipolar diplomatic strategy he had sought to pro-

mote, at least until Russia had rebuilt its economy.

The consequences for Russian-Turkish relations

were almost immediate, as Russia began to prize

Turkey as an economic partner instead of con-

fronting it as a geopolitical rival. Thus in October

1998, Russia refused to grant diplomatic asylum

to Kurdish rebel leader Abdullah Ocalan. Next,

Moscow acquiesced in the deployment of the SAM-

300 system on the Greek island of Crete instead of

on Cyprus. Then, Moscow indicated it would not

oppose the Baku-Tibilisi-Ceyhan pipeline. Finally,

Moscow stepped up its efforts to find external

funding for the Blue Stream natural gas pipeline,

which it made the centerpiece of its policy toward

Turkey.

This change in policy direction toward Turkey

was reinforced after Vladimir Putin became Rus-

sia’s president in January 2000. In October 2000

Russian prime minister Mikhail Khazyanov came

to Ankara and stated that cooperation, not con-

frontation, was the centerpiece of Russian policy

toward Turkey, and in November 2001, at the

United Nations, then Turkish Foreign Minister Is-

mail Cem and Russian Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov

signed an action plan for Turkish-Russian cooper-

ation in Eurasia.

Tensions remained over Kurdish and Chechen

issues, over Russian military deployments in Tran-

scaucasia, and over the passage of Russian oil

through the straits. However, by the beginning of

2003, even with an Islamist now heading the Turk-

ish government, Russian-Turkish relations were

better than at any time in the last 500 years.

Whether this rather halcyon condition will con-

tinue is a question only the future can decide.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; FOREIGN TRADE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Freedman, Robert O. (2002). Russian Policy toward the

Middle East since the Collapse of the Soviet Union. Uni-

versity of Washington.

Freedman, Robert O. (2002). “Russian Policy toward the

Middle East under Putin.” Demokratizatsia 10 (4).

Harris, George. (1995). “The Russian Federation and

Turkey.” In Regional Power Rivalries in the New Eura-

sia, ed. Alvin Z. Rubinstein and Oles Smolansky.

New York: M. E. Sharpe.

Insight Turkey: Special Issue Devoted to Turkey and Russia

from Competition to Convergence 4 (2), April–June

2002.

Sezer, Duygu Bazoglu. (2001). “Russia: The Challenges

of Reconciling Geopolitical Competition with Eco-

nomic Partnership.” In Turkey in World Politics, ed.

Barry Rubin and Kemal Kirisci. Boulder, CO: Lynne

Riener.

Sezer, Duygu Bazoglu. (2000). “Turkish-Russian Rela-

tions: From Adversity to ‘Virtual Rapprochement’.”

In Turkey’s New World, ed. Alan Makovsky and Sabri

Sayari. Washington, DC: Washington Institute for

Near East Policy.

R

OBERT

O. F

REEDMAN

TURKEY, RELATIONS WITH

1588

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

TURKMENISTAN AND TURKMEN

The Turkmen are probably the least–known major

ethnic group in Central Asia, as they are a

tribal–based people who live in the desert region be-

tween Iran and Uzbekistan. Turkmen are Sunni

Muslims, although the affinity with Islamic prac-

tices is weaker than those of other ethnic groups

in the region. Linguistically, the Turkmen language

is part of the larger Turkic language group, and is

considered to be closer to Azeri and Turkish, to the

point of being mutually intelligible.

The Turkmen are known in the region as be-

ing nomadic peoples who have rarely been incor-

porated into regional empires. While a significant

percentage of Turkmen live in the country of Turk-

menistan, many live in bordering states. It is esti-

mated that more than one million Turkmen live in

Iran, slightly fewer in Iraq and Afghanistan, re-

spectively, and nearly 500,000 live in Uzbekistan.

The country of Turkmenistan itself is home to 4.8

million people, of whom 3,696,000 (77%) are eth-

nic Turkmen. The significant minorities in Turk-

menistan are Uzbeks (9.2%), Russians (6.7%), and

Kazakhs (2.0%). The capital city of Ashgabat has

an estimated population between 600,000 (official)

and one million (unofficial). This discrepancy be-

lies a rather unusual problem in the country: there

has not been an official census since the Soviet–era

census of 1989, thus it is difficult to ascertain with

some level of confidence most population figures.

The government declared at the beginning of 2000

that the population would exceed five million as a

result of significant return migration of Turkmen

from around the world. Non-governmental ob-

servers have not corroborated this figure, nor have

they done the same for the current government

claim that there are 5.7 million Turkmen living in

the country.

The early history of the Turkmen is generally

told by outside writers and observers. Turkmen (or

Turcomen) tribes were noted by early travelers in

the region and were often the source of concerns,

for the Turkmen were noted for looting caravans

and raiding settlements. Such stereotypes plagued

the Turkmen up through the nineteenth century,

TURKMENISTAN AND TURKMEN

1589

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

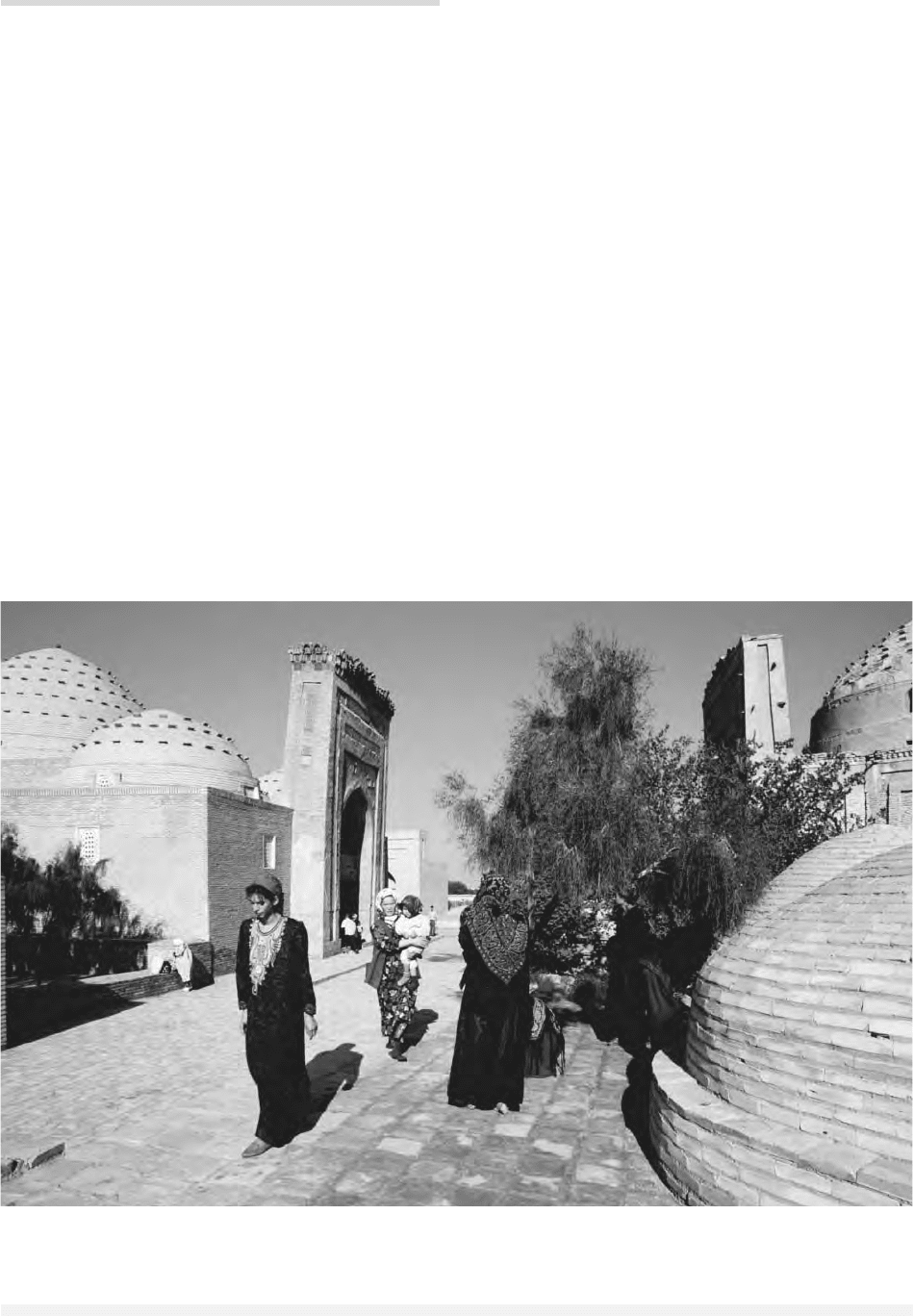

Women walking along a street in Turkmenistan, one of the most isolated regions of the Soviet empire. © G

ÉRARD

D

EGEORGE

/CORBIS

when the Russian Empire expanded to the region

known as Transcaspia. Since the 1700s, Russian of-

ficials had heard complaints of Turkmen raiders

taking Russian settlers in what is now Kazakhstan

and selling them into slavery. In the 1870s, it was

decided that the Russian empire should incorporate

the region of Transcaspia into their southern hold-

ing. In 1880, Russian forces launched from the port

of Fort Alexandrovsk along the eastern banks of

the Caspian Sea and headed eastward. Initially re-

pelled at the fortress of Goek Tepe, they regrouped

under the leadership of General Skobelev and sub-

dued the Turkmen resistance in the following year.

The final southernmost border of the Russian em-

pire was established in 1895 in a treaty with Great

Britain, effectively ending any competition over

Central Asia in the so–called Great Game.

However, tsarist control of Transcaspia was

short–lived. With the outbreak of World War I,

there was a concurrent increase in tribal activity

against their Russian overlords. Turkmen partici-

pated in the 1916 draft law rebellion and effectively

became autonomous with the collapse of the Rus-

sian empire in 1917. Throughout the Russian Rev-

olution and Civil War, the region of Transcaspia

was under the control of various competing pow-

ers, including a Turkmen tribal leader named Ju-

niad Khan, as well as forces from the British Army

who were sent to protect Allied interests in the re-

gion.

Eventually, the region fell under the control of

the Red Army as the Bolshevik Revolution and civil

war came to a close. The actual notion of a Turk-

men state was not realized until the twentieth cen-

TURKMENISTAN AND TURKMEN

1590

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Garabil

Plateau

K

a

r

a

k

u

m

s

k

i

y

K

a

n

a

l

K

H

R

E

B

E

T

K

O

P

E

T

D

A

Garagum

T

u

r

a

L

o

w

l

a

n

d

C

h

i

n

k

K

a

p

l

a

n

k

y

r

A

m

u

D

a

r

'

y

a

T

e

d

z

h

e

n

M

u

r

g

a

b

G

u

s

h

g

y

S

u

m

b

a

r

A

t

r

e

k

Caspian

Sea

Garabogazköl

Aylagy

Sarykamyshskoye

Ozero

Nebitdag

Türkmenbashi

Dashhowuz

(Tashauz)

Köneürgench

Chärjew

(Chardzou)

Bukhoro

Mary

Mashhad

Ashkhabad

Cheleken

Kum

Dag

Kizyl

Atrek

Kara-Kala

Yerbent

Gyzylarbat

Tejen

(Tedzhen)

Bayramaly

Andkhvoy

Repetek

Qarshi

Chagyl

Kizyl

Kaya

Sandykachi

Kerki

Burdalyk

Farab

Gazanjyk

Kyzylkup

Bakhardok

Büzmeyin

Gushgy

IRAN

KAZAKHSTAN

UZBEKISTAN

AFGHANISTAN

W

S

N

E

Turkmenistan

TURKMENISTAN

200 Miles

0

0

200 Kilometers

50 100 150

50

100 150

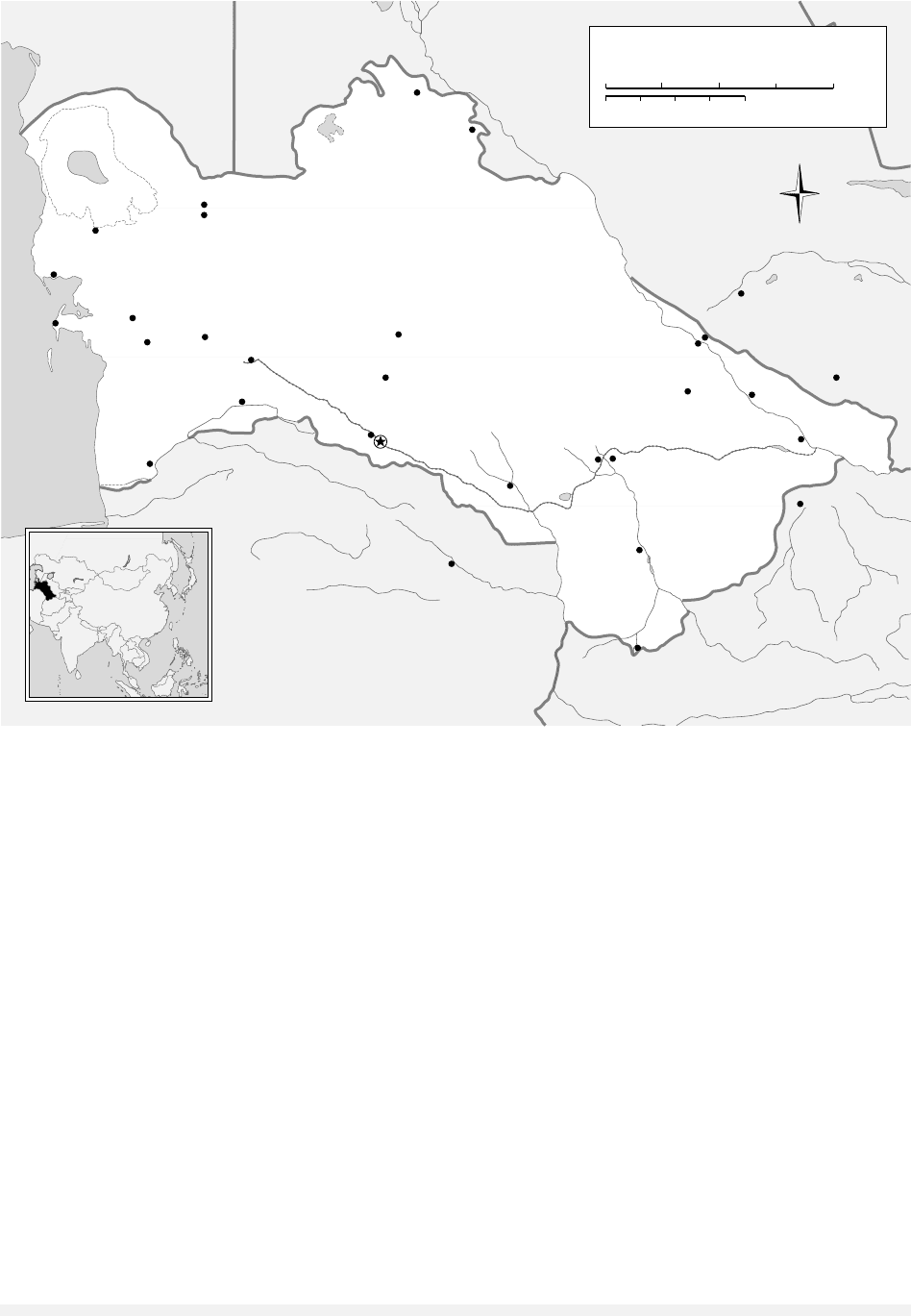

Turkmenistan, 1992. © M

ARYLAND

C

ARTOGRAPHICS

. R

EPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

tury, with the creation of the Turkmen Soviet So-

cialist Republic in 1924. Carved out of the territo-

ries between Uzbekistan and the bordering

countries of Iran and Afghanistan, Turkmenia,

later called Turkmenistan, was created for the tribal

groups in the region. These nomadic tribes, from

the Tekke, Yomud, and others, slowly developed a

common Turkmen identity. Through the period of

Soviet rule, Turkmenistan was one of the least–in-

tegrated union republics in the Soviet Union. It was

noted for providing raw materials such as cotton

and gas to the country’s planned economic system.

It was also viewed as the strategic front line against

U.S.–supported Iran.

In 1991 the Soviet Union collapsed and, like the

other union republics, Turkmenistan became an in-

dependent state. The First Secretary of the Turk-

men Communist Party was declared president, first

of the Turkmen S.S.R. and later the Republic of

Turkmenistan. Saparmurad Niyazov has been

president ever since. In the process, he has created

a strong cult of personality that includes ever-

visible displays of his pictures, statues, and overall

domination of the state–run media. His work of the

late 1990s, the Rukhnama, has become a spiritual

foundation for the Turkmen state and is something

that all Turkmen must learn. Indeed, any opposi-

tion to Turkmenbashi Birigi (Father of the Turk-

men, the Great) centers on challenging this

personalistic rule.

Economic development in the country remains

a paradox. In spite of a great potential in energy

wealth, it remains mired in poverty. And while

there are magnificent new buildings in the center

of the capital city of Ashgabat, the countryside is

dotted with substandard housing and living condi-

tions. Turkmen traditionally have been nomadic

herders, with an economy that is relatively autar-

kic. However, since independence, there has been a

push to exploit the oil and gas reserves of the coun-

try. Because of an inability to find reliable, paying

customers, Turkmenistan has not been able to ben-

efit greatly from this natural resource. As of the

early twenty–first century, Turkmenistan is listed

as having 150 trillion cubic feet of gas, which is

one of the top ten deposits in the world. However,

a lack of firm agreements with energy companies

has resulted in much of this remaining unexplored.

The estimated 2002 gross national product

(GDP) of the country was $21.5 billion, resulting

in an estimated purchasing power parity (PPP) of

$4,480 per capita. However, real per capita income

was closer to $1,000 with most living on less than

$200 per annum. An artificial exchange rate, vast

corruption, and the concentration of wealth at the

top level all have created conditions of abject

poverty for the majority of Turkmen. Trade re-

mains limited to countries such as Russia and

Ukraine, the latter of which uses barter deals to fi-

nance Turkmen gas imports. There are also mod-

est trade relations with neighboring Iran,

capitalizing on a rail link that crosses the Turk-

men–Iranian border.

Because Turkmenistan neighbors Uzbekistan

and Kazakhstan to the north, and Afghanistan and

Iran to the south, these four states, plus Russia,

play a decisive role in Turkmen foreign policy.

However, tempering any effort at expanding rela-

tions is the current Turkmen foreign policy of “pos-

itive neutrality,” which was declared in December

1995. According to this concept, Turkmenistan is

not to be part of regional alliances and security

arrangements. Thus, while it is technically part

of the NATO Partnership for Peace program and

the Commonwealth of Independent States, Turk-

menistan rarely participates in conferences and

meetings and never participates in joint security

exercises. The magnitude of internal problems,

though, may eventually compel the Turkmen gov-

ernment to more actively engage with outside

states, particularly if it ever hopes to benefit from

the energy reserves that have been underutilized.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; ISLAM; NATIONALITIES POLICIES,

SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allworth, Edward, ed. (1994). Central Asia: 130 Years of

Russia Dominance, A Historical Overview. Durham,

NC: Duke University Press.

Bennigsen, Alexandre and Wimbush, S. Enders. (1985).

Muslims of the Soviet Empire: A Guide. London: C.

Hurst.

Capisani, Giampaolo R. (2000). The Handbook of Central

Asia: A Comprehensive Survey of the New Republics.

New York, I. B. Tauris.

Cummings, Sally, ed. (2002). Power and Change in Cen-

tral Asia. London: Routledge.

Kangas, Roger. (2002). “Memories of the Past: Politics in

Turkmenistan.” Analysis of Current Events 14(4):

16–19.

Niyazov, Saparmurat. (1994). Unity, Peace, Consensus, 2

vols. New York: Noy Publishers.

Niyazov, Saparmurat. (2002). Rukhnama. Ashbagat,

Turkmenistan: Government of Turkmenistan.

TURKMENISTAN AND TURKMEN

1591

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Ochs, Michael. (1997). “Turkmenistan: The Quest for

Stability and Control.” In Conflict, Cleavage, and

Change in Central Asia and the Caucasus, ed. Karen

Dawisha and Bruce Parrott. Cambridge, UK: Cam-

bridge University Press.

R

OGER

K

ANGAS

TUR, YEVGENIA

(1815–1892), Russian journalist, writer, critic, and

author of children’s books.

Born Elizaveta Vasilievna Sukhovo-Kobylina,

Tur was a well-known salon hostess, prose writer,

journalist, critic, and author of children’s fiction.

The sister of the playwright Alexander Sukhovo-

Kobylin and the artist Sofia Sukhovo-Kobylina, she

was the first woman to win a gold medal from the

Imperial Academy of Arts. Her son, Yevgeny Salias,

became a popular author of historical fiction.

Tur began her career in Russian letters as a

translator and proofreader for Teleskop (Telescope),

a prominent journal in the 1830s. She was ro-

mantically involved with its editor, and her tutor,

Nikolai Nadezhdin, but her family forbade the

match because they did not want her to marry a

seminarian. In 1837 she reluctantly married Count

Andrei Salias de Tournemire, a French citizen. Af-

ter spending her dowry, Salias was exiled to France

in 1844 for fighting a duel. Tur became a writer,

in part, to support their three children. She was

one of the first women in Russia to earn a living

by writing.

Tur’s salon in Moscow included some of the

most important intellectuals of the day: the au-

thors Konstantin Leontiev and Ivan Turgenev, the

poet Nikolai Ogarev, the historians Timofei Gra-

novsky and Peter Kudriavtsev, and the journalist

Mikhail Katkov. Salons were fruitful ground for

cultural production, and Tur’s was no exception.

Her first published fiction was a novella, Oshibka

(A Mistake) in 1849. She then published several

novellas and novels, the most famous of which is

Antonina (1851). These stories had a large reader-

ship. They were published in the most widely cir-

culated journals of the day (Otechestvennye zapiski,

Russkii vestnik, and Sovremennik), as well as in sep-

arate editions, and her works were reviewed by

such luminaries as Ivan Turgenev and Nikolai

Chernyshevsky.

Tur edited the fiction section of Katkov’s Russky

vestnik from 1856 to 1860 and then published and

edited a journal, Russkaya rech (Russian Speech), in

1861. The journal’s subtitle indicates its scope: “A

Review of Literature, History, Art, and Civic Life in

the West and in Russia.” Tur stopped publication

in 1862 and, to avoid investigation by the Third

Section, moved to Paris, where she lived for ten

years and again hosted a salon. In these years she

worked closely with Alexander Herzen; she also

published a regular column, “Paris Review,” in An-

drei Kraevsky’s newspaper Golos (The Voice). As a

critic, Tur’s intellectual range was broad—she wrote

articles on Jules Michelet, George Sand, Mme. de

Recamier, Charlotte Brontë, and Elizabeth Fry, as

well as Turgenev, Dostoevsky, and Leo Tolstoy.

Each of her essays is a rich engagement with aes-

thetic and social issues.

In her fiction, criticism, and journalism Tur ad-

dressed the “woman question,” one of the foremost

social issues of the day. In her fiction she often re-

versed common cultural stereotypes about women

(such as making the unmarried woman the arbiter

of moral goodness in Oshibka and creating a su-

perfluous man who is not noble in Antonina). In

her journal Tur often published fiction by women

writers. In her criticism she addressed the issue of

the position of women in society, both through

ironic, incisive assessments of Michelet, Proudhon,

and others and in a debate with the educator Na-

talia Grot.

In 1866 Tur began writing exclusively for chil-

dren. These works were extraordinarily well received

and went into many editions. Tur’s children’s fic-

tion, too, became an important cultural influence,

mentioned as formative by Zinaida Gippius, Ma-

rina Tsvetaeva, and others.

See also: JOURNALISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Costlow, Jane. (1991). “Speaking the Sorrow of Women:

Turgenev’s ‘Neschastnaia’ and Evgeniia Tur’s ‘An-

tonina.’” Slavic Review 50 (2): 328–35.

Gheith, Jehanne. (2003). Finding the Middle Ground:

Krestovskii, Tur, and the Power of Ambivalence in Nine-

teenth-Century Russian Women’s Prose. Evanston, IL:

Northwestern University Press.

Gheith, Jehanne. (1996 ). “The Superfluous Man and the

Necessary Woman: A ‘Re-vision’.” Russian Review 55

(2): 226–44.

J

EHANNE

M. G

HEITH

TUR, YEVGENIA

1592

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY