Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

regime during the more than half a century from

Catherine’s rule to the Crimean War and the sub-

sequent Emancipation. Exemptions from taxation

and a stagnant industrial economy meant that tax

revenues did not increase much. Transcaucasia be-

gan to supply customs revenues from the 1830s,

but the new areas of the southern fringe were ex-

pensive to conquer and hold. Fiscal inadequacy be-

came painfully clear when Russia’s poorly supplied

troops were defeated at Sevastopol by English,

French, and Turkish forces. That the Russian roads

and river routes were so obviously inadequate for

mobilization led to great interest in expensive and

extensive railroad projects, requiring both more

money and new industries.

The late nineteenth century was a period of

rapidly rising governmental outlays, doubling be-

tween 1861 and 1890, and again between 1901

and 1905. Railroad building in this vast country

accelerated, primarily for military purposes; debt

service, health, and education also increased their

share in state expenses, though the latter two were

still small by international standards. To meet these

expenditures, the government was able to increase

indirect tax revenues, chiefly on vodka, but also by

its monopoly on the sale of sugar, tobacco,

kerosene, and matches. As was understood, reduced

peasant net incomes meant more grain for export.

Royalties and transportation tariffs on coal and

iron also increased. Customs duties rose signifi-

cantly, both as a result of higher rates and larger

import volumes. Tax policy protected industry at

the expense of agriculture, as direct taxes on com-

pany profits and capital plus redemption payments

hardly increased at all between 1890 and 1910.

Despite some discussion of this possibility be-

fore World War I, most individual incomes were

not taxed, but apartment rents and salaries of civil

servants and joint-stock company employees were.

This pattern points to the strongly regressive na-

ture of tsarist taxation. According to estimates by

Albert L. Vainstein, the tax burden on peasants av-

eraged 11 percent of their total income in 1913,

but probably more than one-quarter of their cash

receipts.

Following the October Revolution, the Bolshe-

vik government depended on confiscations and fiat

money, but this chaotic strategy of covering ex-

penditures soon led to peasant uprisings, and the

government had to switch to a tax in kind (prod-

nalog)—replaced by cash in 1924—on the peasantry.

After meeting their obligations, rural agriculturists

could sell their surpluses on the local market. How-

ever, government efforts to keep the procurement

price for grain low increased the actual surplus

taken. Moreover, the nepmen had to pay a tempo-

rary tax on super-profits starting in 1926.

During the Stalinist period the government

greatly increased the burden of taxation to an es-

timated 50 percent of household income. As shown,

the principal mode of taxation was on the nation-

alized manufacturing and mining sectors, plus

heavy exactions in kind from the collective and

state farms. The Finance Ministry also conducted

compulsory bond sales, but these were phased out

during the 1950s.

In more recent Soviet times the regime imposed

a mild income tax on employees, with a top rate

of 13 percent above a certain exempt amount. But

authors, physicians in private practice, tutors,

landlords, craftsmen and like independents would

pay at treble these rates or up to a marginal rate

of 81 percent. Bachelors (and small families until

1958) paid a 6 percent surtax, but military per-

sonnel, students, and dwarfs were exempt. There

was also a fairly stiff tax (from 12 to 48% by 1951)

on money and imputed incomes from private plots

in addition to a small tax on kolkhoz net income.

This was in addition to forced deliveries at lower

than market prices.

Soviet authorities strongly preferred indirect

taxes over those imposed directly on persons. Ap-

parently they believed workers would be more sen-

sitive to their wages and wage differentials than to

the prices they paid—money illusion. However, af-

ter 1947 they also endeavored to reduce official

prices on goods of mass consumption.

While the turnover tax remained the single

largest source of revenue until the 1960s, the type

TAXES

1523

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

1940 1965 1984

Total Revenue (billion rubles) 18.0 102.3 376.7

Turnover tax 59% 38% 27

Payments from profits 12 30 31

Cooperatives’ taxes 2 1 1

Mass bond sales 5 < 1 < 1

Direct taxes 5 8 8

Social insurance contributions 5 5 7

“Other” 12 17 27

SOURCE: Narodnoe Khoziaistvo (National Economy), 1973, 1978,

and 1984. Courtesy of the author.

Table 1.

of tax which increased the most during later So-

viet times was that on profits. In 1950 the turnover

tax accounted for 56 percent of the total, while de-

ductions from profits provided only about 10 per-

cent. By 1970, however, turnover tax declined to

32 percent, while deductions from profits rose to

35 percent of the consolidated USSR budget. How-

ever, the distinction between these two taxes is not

sharp: both are enterprise taxes unrelated to the

ability of citizens to pay.

To these taxes on profits, which after all be-

long to the state as owner, might be added retained

profits devoted to state-mandated investments. Af-

ter 1965 the regime added a small charge on net

capital and broader rental payments in addition to

remittances of the free remainder of profits. The

miscellaneous category included large and rising

profits from foreign trade—for example, on im-

ported grain or exported oil—a stamp duty on le-

gal documents, an inheritance tax, a local property

tax, and a tax on automobiles, boats, and horses.

All this added up to a considerable burden of tax-

ation—approximately 45 percent of Soviet national

income in the postwar period, about half again as

much as in the United States and among the top

tax-collection rates on the European continent.

Nevertheless, except in oil boom years, the budget

usually concealed a 2 to 8 percent deficit, financed

by monetary emissions and resulting in inflation

during the 1980s especially.

Some of the revenues mentioned above are re-

tained by local or republican governments for their

own expenditures. This was particularly high in

the less developed regions of Central Asia, as part

of the regional subsidy characteristic of Soviet

welfare colonialism, as it has been called.

See also: ALCOHOL MONOPOLY; BEARD TAX; TAX,

TURNOVER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gregory, Paul, and Stuart, Robert. (1998). Russian and

Soviet Economic Performance and Structure, 6th ed.

Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

TAXES

1524

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

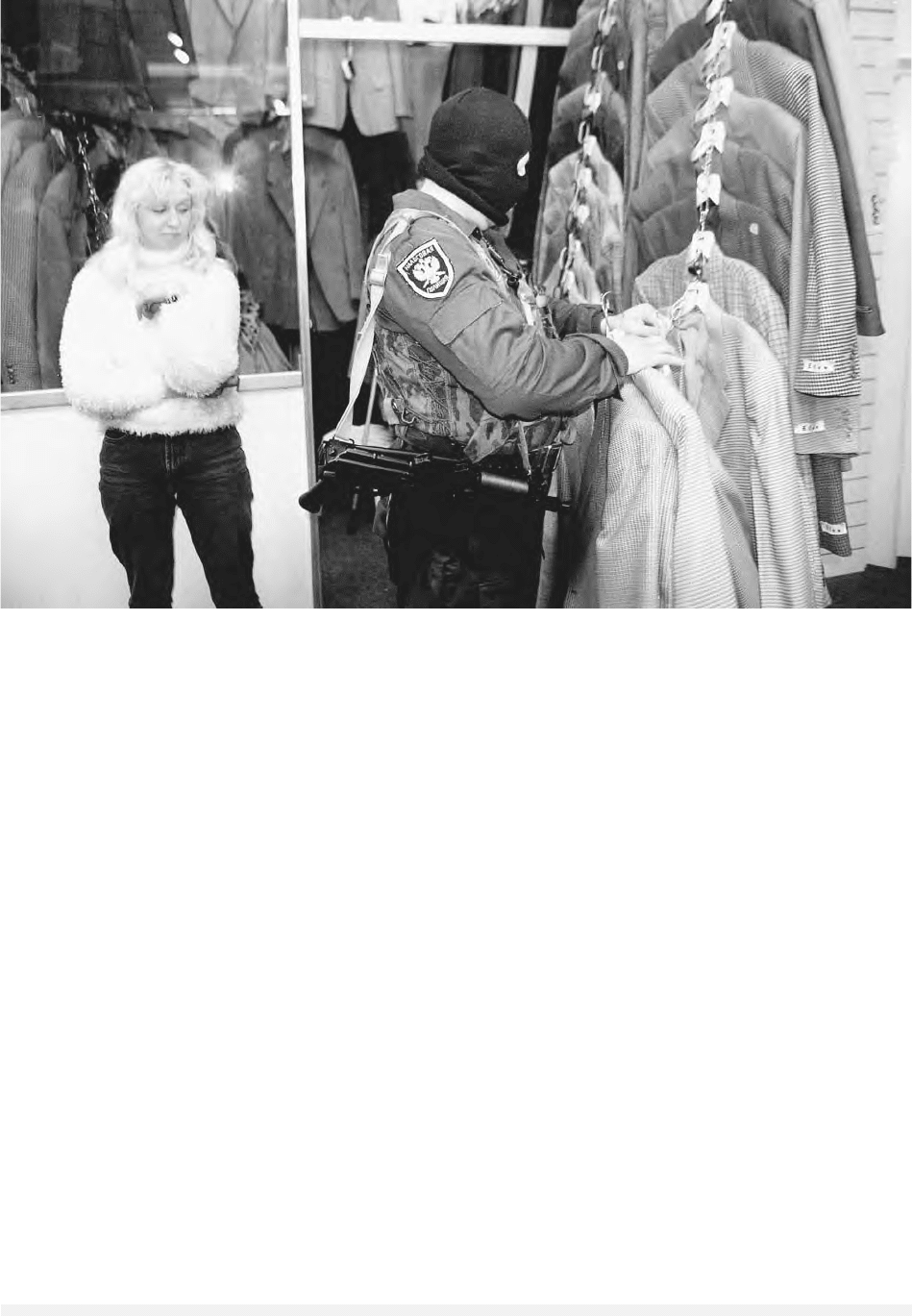

A female entrepreneur watches as a Moscow tax-police inspector confiscates goods from her unlicensed shop. P

HOTOGRAPH BY

A

LEXANDER

S

ALYUKOV

/A

SSOCIATED

P

RESS

. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

Holzman, Franklyn D. (1955). Soviet Taxation. Cam-

bridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kahan, Arcadius. (1985). The Plow, the Hammer, and the

Knout. An Economic History of Eighteenth-Century Rus-

sia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

M

ARTIN

C. S

PECHLER

TAX, TURNOVER

Turnover tax (nalog s oborota) was a tax on enter-

prise gross output, the main source of government

revenue during the first several decades of Soviet

planned economy, officially considered part of the

surplus product in Marxist terms. It was intro-

duced in 1930 for the purpose of unifying previ-

ously diverse taxes.

The difference between the final retail price for

consumer goods (and most fuels) and the indus-

try’s wholesale price, as set by the Soviet pricing

authorities, less any handling charges, is the

turnover tax. (Before 1949 this tax was also ap-

plied to producer goods for reasons of fiscal con-

trol.) Sometimes this levy was imposed as a unit

tax, as a percentage of the sale price, or in other

ways. Regardless of the method of collection, the

turnover tax rate is thus the difference divided by

the wholesale (or retail) selling price. These rates

differed widely. In the case of agricultural prod-

ucts, the turnover tax comes from the difference

between the procurement price and that at which

the produce is resold by state organs. On salt and

vodka, the turnover tax resembled an excise tax. In

1975 about one-third of the entire revenue from

turnover taxes came from wines and spirits, hence

any effort to reduce drinking, to the extent they

were successful, posed a fiscal dilemma, as the

Mikhail Gorbachev campaign discovered.

The turnover tax was administratively simple.

Collecting the tax was easier from the relatively

small number of industrial enterprises and whole-

sale organizations, most of which had decent ac-

counts. Income taxes would have had to be collected

from millions of citizens, many of whom were still

illiterate or at least innumerate. The variable

markup allowed retail prices to be changed when

inventories warranted, without altering the indus-

try wholesale price on which planning indices de-

pended. For example, turnover taxes on food were

lowered several times during the 1950s to allow

the state to pay higher procurement prices with-

out affecting politically sensitive retail prices. A

similar situation applied to fuels for household con-

sumption. From 1954 until the late 1960s, official

retail prices were held approximately constant,

quite probably to save administrative effort. It also

permitted certain prices to be disproportionately

low, such as those on children’s clothing and ap-

proved reading material.

As compared to other sources of revenue, the

turnover tax was quite large in the 1930s, but fell

in relation to taxes on profits and incomes during

the 1950s.

See also: TAXES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bergson, Abram. (1964). The Economics of Soviet Planning.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Holzman, Franklyn. (1974). “Financing Soviet Economic

Development.” In William L. Blackwell, ed., Russian

Economic Development from Peter the Great to Stalin.

New York: New Viewpoints.

Nove, Alec. (1986). The Soviet Economic System, 3rd ed.

Boston: Allen & Unwin.

M

ARTIN

C. S

PECHLER

TBILISI See TIFLIS.

TCHAIKOVSKY, PETER ILYICH

(1840–1893), Russian composer.

Arguably the most famous Russian composer,

Tchaikovsky was the first to achieve renown be-

yond Russia’s borders and establish a place for

Russian music in the repertories of Western con-

cert halls and musical theaters. The first profes-

sional Russian composer to receive a thorough

musical education, the import of Tchaikovsky’s

achievement owes much to his mastery of the

dominant nineteenth-century musical genre: the

symphony. Yet Tchaikovsky’s enormous range,

versatility, and output—he composed in all the ma-

jor genres, including symphonies, operas, ballets,

chamber works, songs, as well as compositions for

solo instruments—assure the composer’s place

among the most popular and prolific European

composers of his day.

Tchaikovsky’s virtual dominance of the Rus-

sian musical scene by the end of his life aroused

TCHAIKOVSKY, PETER ILYICH

1525

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the envy of the nationalist composers known as

the Mighty Handful, yet Tchaikovsky’s ability to

adapt native folk material to established Western

compositional structures proved more successful

than their more earnest attempts to craft from

those materials a unique native musical language.

Four Tchaikovsky masterworks, representing three

genres in which Tchaikovsky particularly excelled,

were the fruits of an unprecedented final creative

flourish: the opera Queen of Spades (1891), the bal-

lets Sleeping Beauty (1889), The Nutcracker (1892),

and the Sixth Symphony (1893).

Although Tchaikovsky’s music was deemed

bourgeois in the relatively radical period following

the 1917 Revolution, these criticisms faded in the

Josef Stalin era, when the monumental art of

the previous century once again found favor,

and Tchaikovsky was hailed as a symphonist par

excellence—the composer’s homosexuality, the per-

ceived melancholy of his music, and his conserva-

tive politics notwithstanding. Tchaikovsky died of

cholera in St. Petersburg in 1893, though a very ac-

tive party of mostly Russian researchers allege the

composer’s death was the result of a suicide brought

about by a crisis over his homosexuality.

See also: MUSIC

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brown, David. (1978–1992). Tchaikovsky: A Biographical

and Critical Study. London: Gollancz.

Orlova, A., ed. (1990). Tchaikovsky: A Self-Portrait. New

York: Oxford University Press.

Poznansky, Alexander. (1991). Tchaikovsky: The Quest for

the Inner Man. New York: Simon and Schuster

Macmillan.

Poznansky, Alexander, and Brett Langston. (2002). The

Tchaikovsky Handbook: A Guide to the Man and His

Music, comp. Alexander Poznansky and Brett

Langston. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University

Press.

Taruskin, Richard. (1997). Defining Russia Musically: His-

torical and Hermeneutical Essays. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

T

IM

S

CHOLL

TECHPROMFINPLAN

In the final stage of the annual central planning

process, Soviet enterprises received each year a com-

prehensive document, the techpromfinplan (tech-

nical-industrial-financial plan), which they were

required by law to fulfill. Divided into quarterly

and monthly subplans, the techpromfinplan gov-

erned the operation of the firm by specifying out-

put targets and input allocations, as well as a large

number of financial characteristics, delivery sched-

ules, capacity utilization norms, labor staffing in-

structions, planned increases in labor productivity,

and other targets. In total, as many as one hun-

dred targets were specified in the techpromfinplan,

the most important of which involved output tar-

gets. Fulfilling output targets, measured either in

quantity or value, formed the basis for calculating

bonus payments for managers and workers.

In a very broad sense, the techpromfinplan was

the means by which Soviet planners’ preferences

were implemented. Social and economic goals set at

the highest level of the political bureaucracy and

conveyed to Gosplan, the State Planning Commit-

tee, were disaggregated by sector, region, and in-

dustry, and sent to individual firms. More narrowly,

the techpromfinplan specified the scope of the firm’s

operations for the year.

The production component of the annual en-

terprise plan identified the quantity, ruble value

(valovaia produktsia), and commodity assortment

of output to be produced. Input allocations, sup-

ply schedules, capacity and resource utilization

norms, as well as other technical indicators, were

devised to support the firm’s ability to fulfill the

production targets. Current production targets

were typically based on a percentage increase in the

firm’s past performance, adjusted for quality-im-

provement targets. The process of planning from

the achieved level meant that Soviet enterprises

were subject to a “ratchet effect” in terms of quan-

tity targets.

The financial component of the enterprise plan

consisted of profitability norms, planned cost re-

ductions, credit plans for purchasing inputs, a

wage bill, and other financial indicators. The com-

prehensive nature of the financial plan paralleled

the production plan, allowing planners to monitor

the firm’s monthly and quarterly output perfor-

mance. Moreover, through the financial plan, min-

isterial officials exercised ruble control (kontrol’

rublem) over the enterprise by restricting access to

financial resources, as well as by redistributing

profits. Unlike managers of firms in market

economies, however, whose performance is mea-

sured in terms of financial indicators, Soviet man-

TECHPROMFINPLAN

1526

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

agers placed highest priority on fulfilling the pro-

duction plan targets.

In addition to production, financial, and distri-

bution components, the techpromfinplan also spec-

ified a variety of labor staffing targets, including

the distribution of labor force by wage classifica-

tions, the total amount of wages that the firm

could pay, average wages by occupational cate-

gory, and planned increases in labor productivity,

but left the manager with some discretion over

staffing issues within these constraints.

Legally obligated to fulfill the techpromfinplan

and motivated by large monetary bonuses paid for

fulfilling output targets, Soviet enterprise man-

agers nonetheless exhibited a significant degree of

flexibility in both the production and distribution

activities of the firm.

See also: CENTRAL PLANNING; PLANNERS PREFERENCES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dyker, David. (1984). The Future of the Soviet Economic

Planning System. Beckenham-Kent: Croom Helm.

Kushnirsky, Fyodor. (1982). Soviet Economic Planning,

1965–1980. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Zaleski, Eugene. (1980). Stalinist Planning for Economic

Growth. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina

Press.

S

USAN

J. L

INZ

TEHERAN CONFERENCE

The Teheran Conference was the first summit

meeting between U.S. President Franklin D. Roo-

sevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill,

and Soviet Premier Josef Stalin. It met from No-

vember 28 through December l, 1943, in Teheran,

Iran. The general purpose of the conference was to

strengthen the cooperation between the Big Three

allies in the conduct of the Second World War and

to determine the outlines of a postwar global or-

der. Though the Western allies—particularly Roo-

sevelt—sought to conciliate the Soviet dictator, the

conference was marked by underlying tension over

differences among the allied leaders. The major

agreement reached was the decision to launch the

long-awaited invasion of Europe (Operation Over-

lord) as a cross-channel invasion of France in May

1944 (later changed to June). For Stalin, this promise

of relief for the Red Army was a major victory.

Considerable discussion of the question of Poland’s

postwar boundaries produced no definitive solu-

tion, though there was a consensus that Poland’s

eastern boundary would be the Curzon line and

that Poland would be compensated in the West with

territories to be taken from Germany. Stalin suc-

cessfully pressed for confirmation of Soviet gains

as a result of the Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression Pact

of 1939. In turn Stalin agreed to engage Japanese

forces in the Pacific theater after the defeat of Ger-

many. There was also agreement to cooperate in a

postwar United Nations organization to maintain

peace. In a separate protocol the Big Three agreed

to maintain the independence, sovereignty, and ter-

ritorial integrity of Iran.

See also: NAZI-SOVIET PACT OF 1939; POTSDAM CONFER-

ENCE; WORLD WAR II; YALTA CONFERENCE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mayle, Paul D. (1987). Eureka Summit: Agreement in Prin-

ciple and the Big Three at Teheran, 1943. Newark: Uni-

versity of Delaware Press.

Sainsbury, Keith. (1985). The Turning Point: Roosevelt,

Stalin, Churchill, and Chiang-Kai-Shek: the Moscow,

Cairo and Teheran Conferences. Oxford: Oxford Uni-

versity Press.

J

OSEPH

L. N

OGEE

TELEOLOGICAL PLANNING

The concept of teleological planning refers to na-

tional economic planning that is directive in char-

acter (planners determine plan directives), as

opposed to genetical planning, indicative in charac-

ter, in which plan targets are influenced by mar-

ket (demand) forces.

The discussion of alternative approaches to na-

tional economic planning was an important com-

ponent of the early development of planning in the

Soviet Union. The teleological school was repre-

sented by major economists such as S. Strumilin,

G. L. Pytatakov, V. V. Kuibyshev, and P. A. Fel’d-

man, while the geneticists were represented by N.

D. Kondratiev, V. A. Bazarov, and V. G. Groman,

all well-known economists. The debate ended with

Stalin’s adoption of the teleological approach.

The distinction between the two different ap-

proaches remains important. The teleological concept

TELEOLOGICAL PLANNING

1527

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

implies that planners’ preferences prevail; that is,

planners determine the objective function of the

economy (e.g., the mix of output by sector or prod-

uct) with consumer preferences being passive. The

genetical approach, on the other hand, has impor-

tant implications for planning in a pluralistic po-

litical setting, in that consumer preferences can

prevail and serve as the basis for plan directives.

The geneticist view is effectively the foundation for

the contemporary development of indicative plan-

ning.

See also: CENTRAL PLANNING; ECONOMIC GROWTH, SO-

VIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carr, Edward Hallett, and Davies, R. W. (1969). Foun-

dations of a Planned Economy, 1926–1929, vols. 1–2.

London: Macmillan.

Gregory, Paul R., and Stuart, Robert C. (2001). Russian

and Soviet Economic Structure and Performance. 7th ed.

New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Spulber, Nicolas. (1964). Soviet Strategy for Economic

Growth. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

R

OBERT

C. S

TUART

TELEVISION AND RADIO

Present-day Russian television and radio have come

a long way. Today’s domestic news and entertain-

ment broadcasts can hardly be told from their

Western counterparts. The successors of Soviet tele-

vision and radio are characterized by a state-of-the-

art style of presentation, modern advertising, and

professional journalism. The Russian mass media

have undergone a series of profound transforma-

tions, notably since the end of the Soviet era, but

they continue to be under the influence of power-

ful interest groups.

Journalism, especially news coverage, is subject

to various restrictions. There is a wide gap between

the official policy, its provision for the freedom of

the media, and the actual situation. The regulation

of television and radio in the Russian Federation has

shown indications reminiscent of the centralized

media control during the Soviet regime. But eco-

nomic influences and the opinion-leading value of

television both create a competitive environment

considered irrevocable and therefore immune to at-

tempts to reinstate a Soviet-like authoritarian rule

over the media, mainly due to Russia’s matter-of-

fact accession to international politics, and liberal

values.

In 2002 the Ministry of Press, Broadcasting,

and Mass Communications (MPTR) registered

3,267 television channels and 2,378 radio stations,

more than half wholly or partly state owned. Al-

most every Russian household owns at least one

television set, whereas a radio can be found in four

out of five households. Many listeners still rely on

the old wire radio through which state-run Radio

Mayak and Radio Rossiya have been broadcasting

their programs. The fact that no fees need to be

paid for broadcast reception contributes to a high

penetration of the population and dominance over

the print sector. Less than a quarter of Russians

read newspapers on a daily basis, and almost half

of those age thirty and younger do not read

newsprint at all. State-owned national TV Channel

One (ORT) and Television Rossiya (RTR) reach prac-

tically all viewers, and together with private chan-

nel NTV achieve 60 percent viewer ratings. The

radio audience ratings are dominated by Radio

Mayak, Radio Rossiya, and private Radio Europe

Plus, Russkoye Radio, and Echo Moskvy.

SOVIET EXPLOITATION OF

MEDIA POTENTIALS

The media’s assignment life was plotted by mass

communication experts from the Politburo and

pursued with measures like enforced subscriptions

to print media and various obstructions to diver-

sity of broadcast programs. From the 1920s on,

wire radio receivers were installed in almost every

household, whereas small and remote villages re-

ceived collective loudspeakers. Because they could

not be switched off, only muted, these primitive

mass information instruments already bore the

sign of inescapability, which transcended into the

1980s. Soviet wireless radio started its career with

its first transmission in 1924 and quickly devel-

oped into a public voice of the party. In the early

Soviet days, broadcasting owned its significance to

widespread illiteracy. Not only could radio and later

television reach large masses of people without

them being able to read, broadcasting influenced

how information was perceived and accepted by the

audience. Television’s potential, though being ex-

perimentally tested since the 1930s, was not ac-

knowledged until decades later.

In 1960 the Central Committee commanded

broadcasting to actively support the propagation

TELEVISION AND RADIO

1528

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

of Marxist-Leninist ideas, and the mobilization of

the working class. Major investments in technical

infrastructure followed and by the end of the decade

Moscow neighborhood Ostankino became home to

the national broadcasting organization. It provided

the Soviet population with two television and four

radio programs. Later accessibility was enhanced,

and further television programs were added. Until

the late 1980s the Soviet Union boasted a uniform

information sphere designed to reach most of its

285 million inhabitants. Television was broadcast

in forty-five union languages, and radio in sev-

enty-one. The programs were centrally produced

in Moscow and transmitted to the far reaches of

the Soviet world. They incessantly stressed the po-

litical meaning of each news item. As there was no

other medium of information, and no access to for-

eign news sources, the audience was inescapably

exposed to propaganda through mass media.

BROADCAST PROGRAMMING

AND AUTONOMY

In Soviet times the majority of television and radio

programming was dedicated to broadcasts of party

sessions and statements by government officials.

Next in importance was news from the economic

sector. Educational and cultural programs fol-

lowed. The only television news show, Vremya,

contained coverage of international events. All pro-

gramming was subject to austere censorship and

depended on one sole information source, the gov-

ernment. The fact that people’s values and their im-

age of the world were given a one-sided direction

through mass indoctrination enhanced the impact

of the new freedom the media experienced when

Soviet society started to unravel.

From 1986 to 1993 the media won a hitherto

unknown autonomy owing to their role in the per-

TELEVISION AND RADIO

1529

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

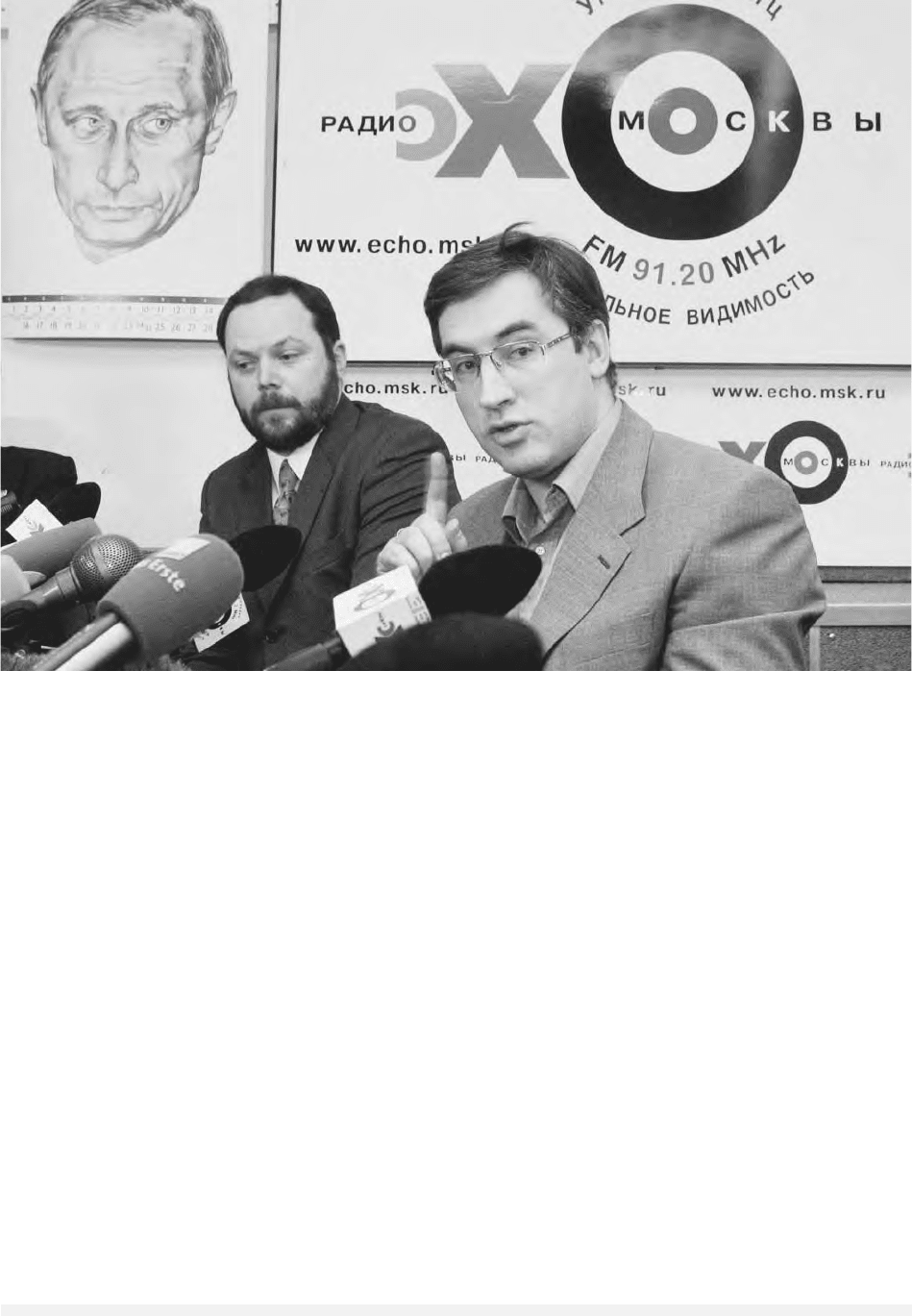

TV6 anchors Andrei Norkin (right) and Vladimir Kara-Murza (left) speak to the media on January 11, 2002, after judges ordered the

closure of the last independent channel on Russian national television. P

HOTOGRAPH BY

I

VAN

S

EKRETKAREV

/A

SSOCIATED

P

RESS

. R

EPRODUCED BY

PERMISSION

.

estroika reforms, and the dissolution of political

structures that rigidly controlled mass communi-

cation. While Mikhail Gorbachev encouraged the

investigation and discussion of state problems, new

leaders fought against old bureaucrats and eco-

nomic obstructions; first the press, then television

and radio, gained momentum. The Russian society

broke into a fragmented mass of people hungry for

Western achievements and individual liberties, and

the media made use of the vacuum created by the

loss of a uniform ideology and morals. Most did

not aim to serve democratic ideals but looked for

financial profits. Not many of the exceptions to this

rule have survived the struggles. Independent

broadcasters, NTV Television, and TV6, formerly

controlled by oligarchs, were recently restrained by

court orders referring to their financial situation.

Radio Echo Moskvy, founded in August 1991, has

retained its independence, although still harrassed

by occasional interferences by the authorities.

PROBLEMS OF OWNERSHIP

AND CONTROL

Privatizations of media outlets during the first

years of the newly founded Russian Federation cre-

ated opportunities not only for the staffs of media

organizations. State-controlled plants and the new

business elite soon profited from the hardships im-

posed on the media by repeated financial crises.

Even in the early twenty-first century, most tele-

vision and radio stations were dependent either on

state subventions or on financing by oligarchs.

Their influence relates to formalities such as li-

censing and provision of technical equipment, as

well as to media content. Reporting often reflects

only two positions, that of the government and the

ruling businessmen. The media may convey oppo-

sitional messages, but not on behalf of society. This

is even more pronounced in the vast regions of the

Russian Federation, where local governors and

plant owners exercise arbitrary power over the

struggling local media industry.

This competition has led to media wars be-

tween businessmen like Boris Berezovsky, Vladimir

Gusinsky, and Vladimir Potanin, who during Pres-

ident Boris Yeltsin’s quest for voting consensus

acquired liberties through behind-the-scenes

arrangements. In Yeltsin’s 1996 campaign, televi-

sion was recognized as effective to influence vot-

ers. Other major players who contributed to the

broadcasting media being used as instruments

of power were at times Prime Minister Viktor

Chernomyrdin, Deputy Prime Ministers Anatoly

Chubais and Boris Nemtsov, and Moscow’s mayor

Yuri Luzhkov. After President Vladimir Putin’s

concerted actions to reinstate central power over

opinion-leading mass media, private competitors

retreated to the print sector and own minor stakes

in broadcasting. Nevertheless, the ownership struc-

tures in the media industry have been characteris-

tically intransparent. It remains difficult to discern

the origin of financial and ruling power over a great

number of media outlets.

In Soviet times the usurpation of the right to

intervene in daily media business was based on the

well-oiled censorship apparatus. Journalists had to

be party members and follow guiding principles

that adhered to government interests. Russian jour-

nalism bears some of these traits into the twenty-

first century. On the one hand, many of the Soviet

journalists have remained in their profession. On

the other hand, many journalists are young, have

put the historical past behind them, and aspire to

meet modern professional standards. They, too,

have to make amends to the kind of censorship im-

posed on them by the special interests of the own-

ers of the media organization. The positive coverage

of state or oligarch activities, or the rumor-based

reporting on competitors’ faults, are also often or-

dered and paid for, not selected by journalistic

processes.

MODERN MEDIA POLICIES

Until 1990 there were no specific laws concerning

the mass media. More than thirty laws and dozens

of decrees have been passed since then. Under the

Soviet regime, two constitutions (1936 and 1977)

alluded to the freedom of expression, which had to

be in accordance with interests to develop the so-

cialist system. Such ideological baggage was dis-

carded by the constitution of the Russian Federation

adopted in 1993, and the Supreme Soviet had in

1990 already passed a law to lift censorship from

the media.

In 1991 the Russian Federation adopted the Law

on Media of Mass Information, which allowed for

fundamental freedoms of the media. It was revised

in 1995 and significantly limited the media’s choice

of diversity for the portrayal of political parties.

Such undemocratic hindrances, along with the lack

of a law conceding to the specific needs of broad-

casting media, continue to the present day. Other

laws are On Procedure of Media Coverage of State

TELEVISION AND RADIO

1530

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Authorities by State Media (1994); On the Defense

of Morality in Television and Radio Broadcasting

(1999); On Licensing of Certain Activities (2001);

and the Doctrine of the Information Security of the

Russian Federation (2000), which links media au-

tonomy with national security.

See also: PERESTROIKA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aumente, Jerome, et al., eds. (1999). Eastern European

Journalism: Before, during, and after Communism.

Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Belin, Laura. (1997). “Politicization and Self-Censorship

in the Russian Media.” <http://www.rferl.org/nca/

special/rumediapaper>.

Casmir, Fred L., ed. (1995). Communication in Eastern Eu-

rope: The Role of History, Culture, and Media in Con-

temporary Conflicts. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

De Smaele, Hedwig. (1999). “The Applicability of West-

ern Media Models on the Russian Media System.”

European Journal of Communication 14:173-89.

Dewhirst, Martin (2002). “Censorship in Russia, 1991

and 2001.” The Journal of Communist Studies and

Transition Politics 18(1):21-34.

European Audiovisual Observatory. (2003). “Television

in the Russian Federation: Organisational Structure,

Programme Production and Audience.” <http://www

.obs.coe.int/online_publication/reports/internews

.pdf>.

Jakubowicz, Karol. (1999). “The Genie Is Out of the Bot-

tle. Measuring Media Change in Central and Eastern

Europe.” Media Studies Journal 13(3):52–59.

Krasnoboka, Natalya. (2003). “The Russian Media Land-

scape.” European Journalism Centre. <http://www

.ejc.nl/jr/emland/russia.html>.

McCormack, Gillian, ed. (1999). Media in the CIS—A Study

of the Political, Legislative and Socio-Economic Frame-

work, 2nd ed. Düsseldorf: The European Institute for

the Media.

McNair, Brian. (1991). Glasnost, Perestroika, and the

Soviet Media. London: Routledge.

Michel, Lutz P., and Jankovski, Jaromir. (2000). “Rus-

sia.” In Radio and Television Systems in Europe, ed. Eu-

ropean Audiovisual Observatory. Strasbourg.

Mickiecz, Ellen, and Richter, Andrei. (1996). “Television,

Campaigning and Elections in the Soviet Union and

Post-Soviet Russia.” In Politics, Media, and Modern

Democracy. An International Study of Innovations in

Electoral Campaigning and Their Consequences, eds.

David L. Swanson and Paolo Mancini. Westport, CT:

Praeger.

Nerone, John C., and McChesney, Robert Waterman eds.

(1995). Last Rights: Revisiting Four Theories of the

Press. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

L

UCIE

H

RIBAL

TEMPORARY REGULATIONS

In response to the assassination of Tsar Alexander

II, Tsar Alexander III enacted a statute enabling the

government to crack down on the political oppo-

sition by imposing emergency regulations more ex-

tensive than any that had previously been enforced.

Although the statute was initially enacted as a tem-

porary measure, it remained on the books until

1917 and has been regarded by historians as the

real constitution of the country. Its implementa-

tion demonstrated, perhaps more than anything

else, that Russia was not a state based on law.

The statute provided for two kinds of special

measures, Reinforced Security (Usilennaya okhrana)

and Extraordinary Security (Chrezvychaynaya

okhrana). The first could be imposed by the Minis-

ter of Internal Affairs or a governor-general acting

with the minister’s approval. The second could be

imposed only with the approval of the tsar. Vague

concerning what conditions could justify placing a

region in a state of emergency, the statute gave the

authorities in St. Petersburg and the provinces con-

siderable leeway in applying it.

The arbitrary powers invested in local officials

(governors-general, governors, and city governors)

under the exceptional measures of 1881 were enor-

mous. Under Reinforced Security, officials could

keep citizens in prison for up to three months, im-

pose fines, prohibit public gatherings, exile alleged

offenders, transfer blocks of judicial cases from

criminal to military courts, and dismiss zemstvo

(regional assembly) employees. Under Extraordi-

nary Security, a region was placed under the au-

thority of a commander in chief, who could dismiss

elected zemstvo deputies, suspend periodicals, and

close universities and other centers of advanced

study for up to one month. Implementation of the

exceptional measures depended largely on the in-

clinations of local officials: in some provinces they

acted with restraint, whereas in others they used

their powers to the utmost. At times up to 69 per-

cent of the provinces and regions of the Russian

Empire were either completely or partially subjected

to one of the various emergency codes.

TEMPORARY REGULATIONS

1531

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

See also: ALEXANDER III; AUTOCRACY; CENSORSHIP;

NICHOLAS II; ZEMSTVO

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Daly, Jonathan W. (1998). Autocracy under Siege: Secu-

rity Police and Opposition in Russia, 1866–1905.

DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

Zuckerman, Frederic S. (1996). The Tsarist Secret Police in

Russian Society, 1880–1917. London: Macmillan.

A

BRAHAM

A

SCHER

TEREM

The separate living quarters of women in Mus-

covite Russia; also, the upper story of a palace, of-

ten with a pitched roof, as in the Terem Palace in

the Moscow Kremlin.

Historians have generally used the word terem

to denote the room or rooms to which Muscovite

royal and boyar women were confined to separate

them from men, both to underpin the custom of

arranging marriages without the couple meeting in

advance and to preserve women’s chastity before

and after marriage. The Mongols are said to have

introduced the terem between the thirteenth and

fifteenth centuries, but this theory is questionable:

The practice of female seclusion reached its height

in the seventeenth century, long after the Mongol

occupation of Russia ended. Recent reassessments

also argue that the terem in the sense of apartments

where women were imprisoned like slaves is partly

a construct of foreign travelers, who were unlikely

ever to have seen or entered one. It matched for-

eign expectations concerning Muscovite orientalism

and servitude. Revisionist historians perceive the

royal terem not as a sign of women’s helplessness

and marginalization, but rather as the physical rep-

resentation of a separate sphere of influence or

power base, with its own extensive staff, finances

and administrative structure. From within it, royal

women dispensed charity, did business, dealt with

petitions, and arranged marriages. These arrange-

ments were replicated on a smaller scale in boyar

households.

This does not mean that Muscovite elite women

were not subjected to restrictions when compared

with their Western counterparts. With the excep-

tion of weddings and funerals, they took no part

in major court ceremonies and receptions, which

were all-male affairs. Balls, masques, and other

mixed-sex entertainments were out of the question,

and the Muscovite court knew no official cult of

beauty. Women used curtained recesses in church,

traveled in carriages shielded by curtains, and wore

concealing clothing. Married women always cov-

ered their hair. Girls were not to be seen by their

fiancés until their wedding. The taboos extended to

portraits from life. Portraits of Muscovite men are

rare, but those of women almost nonexistent. In

the Kremlin the sense of exclusiveness and mystery

cultivated by the tsar naturally extended to the

women, whose quarters were out of bounds to all

except designated noblewomen, priests, and family

members. Attached to the terem, the Golden Hall

of the Tsaritsy, decorated with frescoes featuring

women rulers from Biblical and Byzantine history,

provided a space for female receptions. Outside the

Kremlin, in the few surviving boyars’ mansions, it

is difficult to identify rooms specifically designated

as a terem, but noblewomen were expected to be-

have modestly. Lower down the social scale segre-

gation was impractical, but at all levels marriages

were arranged by parents.

Peter I (r. 1682–1725) is credited with abolish-

ing the terem, to the extent that he forced women

to socialize and dance with men, take part in pub-

lic ceremonies, and adopt Western fashions. Even

so, as elsewhere in Europe, Russian royal palaces

preserved the equivalents of the king’s and queen’s

apartments, while in the provinces older traditions

of female modesty survived.

See also: MUSCOVY; PETER I, WESTERNIZERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Boskovska, Nada. (2000). “Muscovite Women during the

17th Century.” Forschungen zur osteuropäische

Geschichte 56:47–62.

Kollmann, Nancy S. (1983). “The Seclusion of Elite Mus-

covite Women.” Russian History 10(2):170–187.

Thyret, Isolde. (2001). Between God and Tsar: Religious

Symbolism and the Royal Women of Muscovite Russia.

DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

L

INDSEY

H

UGHES

TER-PETROSSIAN, LEVON

(b. 1945), Armenian philologist and statesman.

The first president of the second independent

republic of Armenia (1991–1998), Levon Ter-

TEREM

1532

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY