Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Vlasov has been interpreted both as a patriotic

opponent of Communism and as a treacherous op-

portunist. The Vlasov movement illustrates the

way in which Nazi policy towards the USSR was

developed by the competing requirements of ideol-

ogy and military expediency and the various agen-

cies involved in policy.

The outbreak of war witnessed popular disaf-

fection within the territories of the USSR. Many

opposed to Stalinism hoped that the Germans

would come as liberators. Hitler saw the war in

racial terms, and his main aim was to acquire liv-

ing space (Lebensraum).

A successful commander, Vlasov had impressed

Stalin. Having fought his way out of the Kiev en-

circlement, he was appointed to repulse the Ger-

man attack on Moscow in December 1941. In

March 1942 Vlasov was made deputy commander

of the Volkhov front and then commander of the

Second Shock Army. For reasons that are still un-

clear, the Second Shock Army was neither strength-

ened nor allowed to withdraw. On June 24, Vlasov

ordered the army to disband and was captured

three weeks later. As a prisoner-of-war, Vlasov met

German officers who argued that Nazi policy could

be altered. Relying on his Soviet experience, Vlasov

believed that their views had official sanction and

agreed to cooperate.

In December 1942 the Smolensk Declaration

was issued by Vlasov in his capacity as head of the

so-called Russian Committee, and was aimed at So-

viet citizens on the German side of the front. In re-

sponse, Soviet citizens began to sew badges on their

uniforms to indicate their allegiance to the Russian

Liberation Army, which in fact did not exist al-

though the declaration referred to it. In the spring

of 1943, Vlasov was taken on a tour of the occu-

pied territories and published his Open Letter,

which attracted much support among the popula-

tion. Hitler was opposed to this and ordered Vlasov

to be kept under house arrest as there was no in-

tention of authorizing any anti-Stalinist move-

ment. Dabendorf, a camp near Berlin, became the

main focus of activity. Mileti Zykov was particu-

larly influential in developing some of the program

at Dabendorf. Finally, on September 16, 1944,

Vlasov met Heinrich Himmler, who authorized the

formation of the Committee for the Liberation of

the Peoples of Russia (KONR, Komitet Osvobozh-

deniya Narodov Rossii). The Manifesto was pub-

lished in Prague on November 14, 1944. Two

divisions were formed, but Soviet soldiers already

serving in the Wehrmacht were not allowed to join.

In May 1945, the KONR First Division deserted

their German sponsors and fought on the side of

the Czech insurgents against SS troops in the city.

Vlasov wished to demonstrate his anti-Stalinist cre-

dentials to the Allies, but when it became clear that

the Americans would not be entering Prague, the

First Division was eventually ordered to disband.

Vlasov was captured, taken back to Moscow, tried,

and hanged as a traitor in August 1946. For many

years, mention of Vlasov and the anti-Stalinist op-

position was taboo in the USSR. Since the 1980s

more material has been published. An attempt to

rehabilitate Vlasov and to argue that he had fought

against the regime—not the Russian people—was

turned down by the Military Collegium of the

Russian Supreme Court on November 1, 2001.

See also: STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Andreyev, Catherine. (1987). Vlasov and the Russian Lib-

eration Movement. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Dallin, Alexander. (1981). German Rule in Russia,

1941–1945: A Study in Occupation Politics, 2nd ed.

London: Macmillan.

C

ATHERINE

A

NDREYEV

VODKA

Prior to the twentieth century, the Russian word

vino indicated the class of beverages known in Eng-

lish as vodka. The term refers to all alcoholic drinks

made from distilling grain. (Confusingly, vino could

also mean wine.) The Russian word vodka usually

referred to the higher grades of spirits.

Precisely when spirits appeared in Russia is dif-

ficult to discern. Some historians note references to

vodka in written chronicles as early as the twelfth

century. Others argue that spirits arrived in Rus-

sia in the late fourteenth century. One source

claims that Livonians and Germans were granted

permission to sell aqua vita, or vodka, in certain

areas of Moscow in 1578. A commonly held view

is that drinks such as present-day vodka spread to

Russia only in the sixteenth century when Russians

learned the art of distilling grain from the Tatars.

The most widely held consensus is that vodka came

from the west in the first half of the sixteenth cen-

tury, but its consumption was initially limited to

foreign mercenaries.

VODKA

1645

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

From the outset, the government exercised con-

trol over the trade in spirits. Beginning in 1544,

the state owned and regulated drink shops (kabaki)

that distilled and sold vodka in the towns. The Law

Code of 1649 extended state control to all the Russ-

ian provinces and established a monopoly over pro-

duction, distribution, and sale of spirits, from which

the nobility were exempt. In the mid-sixteenth cen-

tury, the state began farming out the rights to

collect taxes on vodka, and by 1767 liquor tax

farming spread throughout the empire as the pri-

mary means of extracting revenues from vodka

until an excise system was set up in 1863. The ex-

cise system, however, made regulation difficult, so

in 1892, Minister of Finance Sergei Witte intro-

duced a reformed state monopoly. Except for a brief

experiment with prohibition from 1914 to 1925,

the state retained a monopoly over the vodka trade

until 1989. Throughout most of the nineteenth and

twentieth centuries, liquor taxes comprised be-

tween 26 and 33 percent of all state revenues.

Historically, peasants drank mead, ale, and beer

on festive occasions. Since vodka involved distill-

ing, peasant households did not have the equip-

ment, technology, or resources to produce their

own. In its quest for revenues, the state expanded

commercial production and sale of vodka to the

rural population throughout the eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries. With the expansion of the

vodka trade, the use of beer was increasingly re-

placed by vodka as the favored ceremonial drink

among the lower classes.

By the nineteenth century, vodka was the sin-

gle most important item in lower-class diets. In the

villages, peasants drank vodka at church festivals,

rites of passage, family celebrations, weddings and

funerals, and any special occasions in the life of the

rural community. Such ceremonial drinking was

as much an obligation as it was a pleasure. Tradi-

tion and custom demanded drunkenness on certain

occasions, and those failing to respond dishonored

themselves before the community. In order to avoid

this stigma, families often spent their last pennies,

and even sold property, to purchase vodka for an

upcoming event. A funeral could not be arranged,

a wedding conducted, or a bargain sealed without

the required amount of vodka. To be binding, every

type of transaction had to conclude with all par-

ties wetting the bargain—sharing a drink of vodka.

Custom established firm norms on the amount of

vodka to be provided, below which a peasant fam-

ily could not go without being shamed.

Vodka was also a valuable exchange commod-

ity used to maintain networks of patronage and

manipulate village politics. Often decisions con-

cerning the levying of taxes, election of officials, or

the punishment of offenders depended upon who

bought whom how much vodka. A defendant or

petitioner could ply village elders with vodka to in-

sure a favorable outcome; this was known as soft-

ening up the judge. Once a punishment had been

decided upon, the perpetrator often treated the vil-

lage to vodka in order to win forgiveness and read-

mittance into the community. It was also common

for the victim to treat the community to vodka,

thereby affirming his or her acceptance of the pun-

ishment.

The political and economic uses of vodka were

linked in the important village institution of work

parties. Seeking to gather as many people as possi-

ble to get an urgent task done, such as repairing a

road or bridge, building a church, or bringing in the

harvest, the host would supply copious amounts

of vodka. The provision of drink signaled his respect

for the peasants, and they reciprocated by working

for respect. Vodka was the reward for their labor,

but more importantly, it symbolized the mutual-

ity of the exchange, reinforcing the web of interde-

pendent relationships in the community.

From the 1890s, as Russia embarked upon a

course of modernization, vodka retained its cen-

trality in the everyday lives of the working classes.

With the beginning of industrialization, millions of

peasants entered the urban workforce bringing

their traditions with them, especially the practice

of wetting the bargain. In the village, sharing a

drink of vodka signified an equitable economic

arrangement had been made. In the hiring market,

former peasants forced potential employers to wet

the bargain before they would agree to the terms

of employment. The toast was a type of social lev-

eling, forcing employers (at least symbolically) to

respect the workers’ dignity and humanity.

Practices at the workplace centered on drinking

vodka strengthened shop solidarities, reinforced hi-

erarchies among workers, and symbolized a rite of

passage into the world of real workers. Among

male workers in shops, commercial firms, and fac-

tories, each new man underwent an initiation rite,

which involved obligatory buying and drinking of

vodka. Often, a newcomer was not addressed by

name but called “Mama’s boy” until he provided

the whole shop with vodka.

VODKA

1646

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

With the accelerated growth of the urban

working class during the rapid industrialization of

the First Five-Year Plan (1928–1933), the practice

of treating with vodka took on greater significance,

and in most factories it became nearly impossible

for workers to receive training or secure the proper

tools without bribing foremen with vodka. It was

quite common for skilled workers to demand pay-

ment in vodka for training new recruits. As with

rural communities, in the factories custom set firm

limits on the amount of drink required. So preva-

lent was the practice of treating, a nationwide sur-

vey conducted in 1991 revealed that the workplace

was the primary place for imbibing. Moreover, in

1993 average consumption levels were placed at

one bottle of vodka for every adult Russian male

every two days.

See also: ALCOHOLISM; ALCOHOL MONOPOLY; FOOD

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Christian, David. (1990). ’Living Water’: Vodka and Russ-

ian Society on the Eve of Emancipation. Oxford: Claren-

don.

Christian, David, and Smith, R.E.F. (1994). Bread and

Salt: A Social and Economic History of Food and Drink

in Russia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Herlihy, Patricia. (2002). The Alcoholic Empire: Vodka and

Politics in Late Imperial Russia. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Phillips, Laura. (2000). The Bolsheviks and the Bottle: Drink

and Worker Culture in St. Petersburg, 1900–1929.

DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

Transchel, Kate. (2000). “Liquid Assets: Vodka and

Drinking in Early Soviet Factories.” In The Human

Tradition in Modern Russia, ed. William B. Husband.

Wilmington, DE: SR Books.

K

ATE

T

RANSCHEL

VOLKOGONOV, DMITRY ANTONOVICH

(1928–1995), Soviet and Russian military and po-

litical figure, historian, and philosopher.

Colonel General Volkogonov was born in Chita

province, the son of a minor civil servant who was

shot in 1937. Without knowledge of his father’s true

fate, Volkogonov entered military service in 1949

and rose rapidly in rank. As a political officer after

1971, he held various posts within the Soviet Min-

istry of Defense, eventually becoming deputy chief

(1984–1988) of the Main Political Administration.

Although known as an ideological hardliner,

Volkogonov’s foreign experiences gave rise to grave

doubts about the Soviet system. Travels in the

Third World taught him that revolutionary lead-

ers sought only cynical advantage from the Sovi-

ets. An academic visit to the West convinced him

that capitalist societies had produced greater equal-

ities than their supposedly egalitarian socialist

counterparts. He was already reading suppressed

writers when he learned the truth about his fa-

ther’s death—that he had been executed as an en-

emy of the people. Hence sprang the desire to expose

the truth about Stalin and his times.

Estrangement from the military-political lead-

ership precipitated Volkogonov’s transfer to the

USSR Institute of Military History. There, while

chief from 1988 to 1991, his subordinates’ revi-

sionist draft history of the Great Patriotic War,

coupled with his growing adherence to democratic

ideals and an unorthodox evaluation of the Stalin-

ist legacy, provoked clashes with the Ministry of

Defense. Following the Soviet collapse, he served

from 1991 to 1995 as security adviser to President

Boris Yeltsin, while simultaneously championing

democratic causes and chairing several parliamen-

tary commissions as a Duma deputy associated

with the Left-Centrist Bloc. Before his turn against

Soviet convention, Volkogonov’s more significant

works, including Marxist-Leninist Teachings about

War and the Army (1984) and The Psychology of War

(1984) reflected orthodox zeal. However, his sub-

sequent conviction that the Soviet system had been

flawed from the beginning permeated his histori-

cal works, including a revisionist biography of

Stalin, Triumph and Tragedy (1990), and later vol-

umes on Trotsky, Lenin, and other significant early

Soviet leaders.

See also: STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Menning, Bruce W. (2003). “Of Outcomes Happy and

Unhappy.” In Adventures in Russian Historical Re-

search, eds. Catherine Freirson and Samuel Baron.

Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Volkogonov, Dmitri. (1991). Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy,

tr. and ed. Harold Shukman. New York: Grove Wei-

denfeld.

Volkogonov, Dmitri. (1994). Lenin: A New Biography, tr.

and ed. Harold Shukman. New York: Free Press.

VOLKOGONOV, DMITRY ANTONOVICH

1647

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Volkogonov, Dmitri. (1998). Autopsy for an Empire: The

Seven Leaders Who Built the Soviet Regime, tr. and ed.

Harold Shukman. New York: Free Press.

B

RUCE

W. M

ENNING

VOLSKY, ARKADY IVANOVICH

(b. 1932), political leader and industrial lobbyist in

the 1990s.

Arkady Ivanovich Volsky began his career in the

military-industrial sector as deputy chief of the

Department of Machines from 1978 to 1984. He be-

came active in politics by serving on several high-

profile committees dealing with industry and gained

national recognition as Mikhail Gorbachev’s special

representative in Nagorno-Karabakh during the

crises there from 1988 to 1990. Volsky is best known

for founding the Union of Science and Industry in

1990, which he renamed the Russian Union of In-

dustrialists and Entrepreneurs after the failed 1991

coup. He used this position to establish the percep-

tion that he spoke for the interests of managers and

business entrepreneurs during the crucial era of pri-

vatization and transition to capitalism. In mid-June

1992 he was a central figure in the formation of the

Civic Union, a broad alliance of political parties and

parliamentary factions that played an important role

in forcing alterations to the program of rapid priva-

tization and economic reform presented by Prime

Minister Yegor Gaidar. Volsky was widely seen as

one of the key forces behind the June 1993 replace-

ment of Gaidar with Viktor Chernomyrdin and oth-

ers who favored a slower transition with a greater

role for incumbent managers. Although Volsky con-

tinued to head the Russian Union of Industrialists

and Entrepreneurs, its influence, and his, peaked in

1993 and rapidly declined thereafter. By the late

1990s privatization had transformed the economic

and political landscape, bringing power and influence

to a small and shifting group of wealthy, well-

connected oligarchs, deeply undermining his claim to

speak for the business class.

See also: CIVIC UNION; PRIVATIZATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lohr, Eric. (1993). “Arkadii Volsky’s Political Base.”

Europe-Asia Studies 45:811–829.

E

RIC

L

OHR

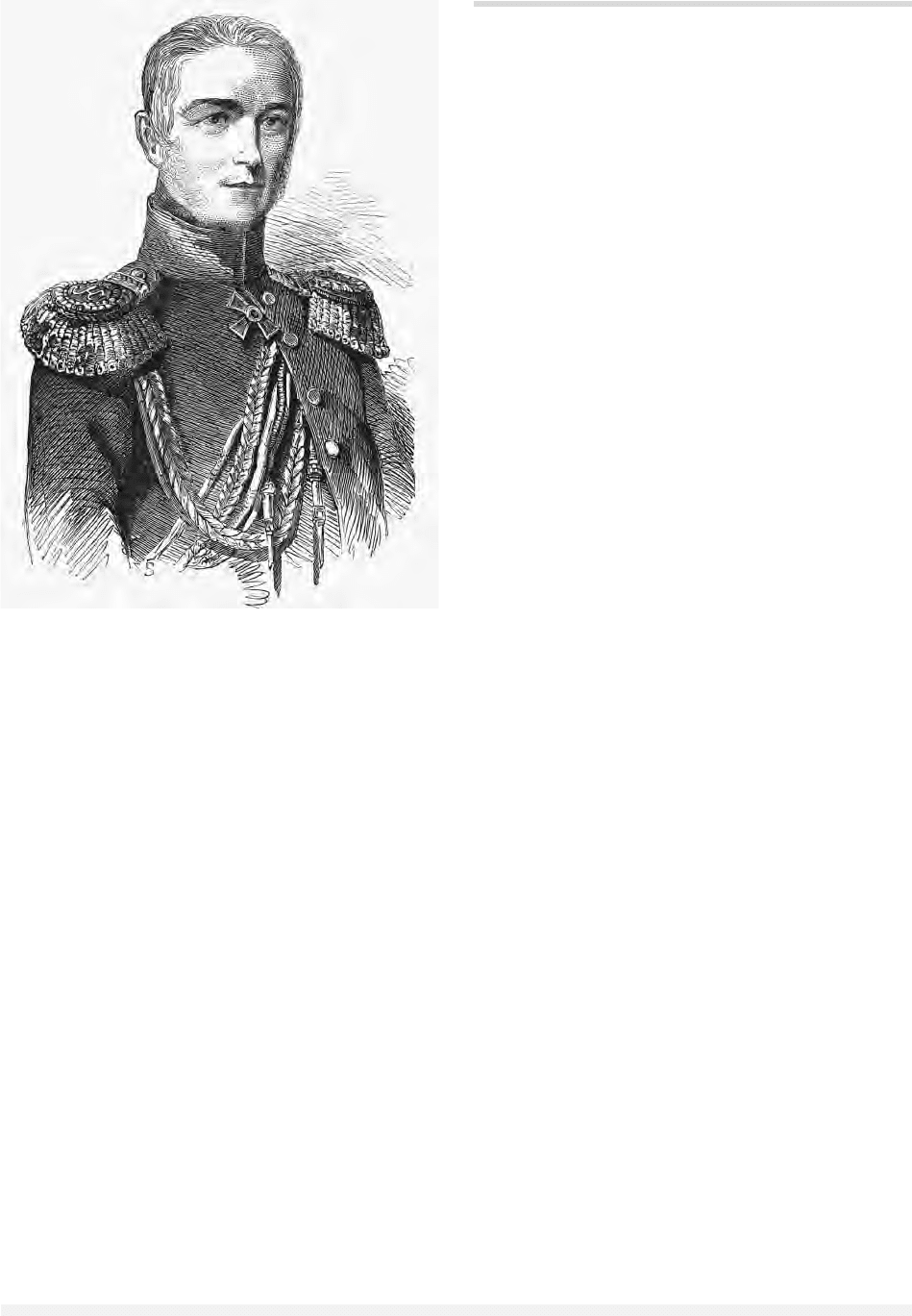

VORONTSOV, MIKHAIL SEMENOVICH

(“Minga”) (1782–1856), leading statesman during

the reigns of Alexander I and Nicholas I.

Although Mikhail Vorontsov was considered a

military hero (his portrait hangs in the Hero’s Hall

of the Hermitage), mainly for his generalship at the

Battle of Borodino (1812) and his command of the

Russian occupation army in France (1815–1818),

his historical significance is due to his rule as

governor-general and viceroy in New Russia and

Caucasia from 1823 to 1854. Born a count in an

illustrious and wealthy family of imperial servi-

tors, he was awarded the titles of field marshal and

most illustrious (Svetleyshy) prince of the Russian

Empire for his service.

Vorontsov was an unshakably loyal servitor to

the emperors, yet thanks to his upbringing in Eng-

land (his father, Semen Vorontsov, was the Russ-

ian ambassador) and an excellent education, as well

as his high social status and fabulous wealth, in

attitude and action he was more Western, liberal,

and business-minded than his conservative Russian

colleagues. The poet Pushkin out of spite called him

“half lord and half merchant.” He was one of Rus-

sia’s largest serf-owners. Although he supported

emancipation in principle, he spurned overtures to

join the Decembrist plotters, many of whom re-

ceived their inspiration in France under his com-

mand. The serfs, he said, could be freed only when

the Emperor decided to do so. Indeed, he was named

by Nicholas I to serve on the commission set up in

1826 to investigate the Decembrist conspiracy.

Vorontsov excelled in the field of imperial ad-

ministration. In New Russia, from its capital

Odessa, and in Caucasia from Tbilisi, his govern-

ment brought vast improvements to the economic

life and sheer physical appearance of these south-

ern regions. He attempted, with limited success, to

improve the operation of the notoriously corrupt

and inefficient imperial bureaucracy. He decentral-

ized decision making in these peripheral territories

of the empire, partly by bringing educated locals

into the civil service. He also fought constantly,

with limited success, for some autonomy from the

jealous central ministries in St. Petersburg. He en-

couraged local businesses. He brought steamboats

from England to improve transportation up the

rivers and on the Black Sea. He established and sup-

ported educational and cultural institutions. He

personally supervised the design and construction

of parks and public buildings in the major cities.

VOLSKY, ARKADY IVANOVICH

1648

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

A bitter opponent of the Crimean War and the

unexpected enmity with his beloved England,

Vorontsov retired in 1854 in failing health, after a

third of a century of service, and died two years

later. In an unusual expression of public admira-

tion for Imperial Russia, public subscriptions paid

for commemorative statues of him in Odessa and

Tbilisi. A beautiful museum dedicated to his good

works and lasting memory, currently open to the

public, is located in one of his former palaces, the

famous Bloor-designed palace in Alupka, not far

from Yalta on the “Russian Riviera,” the beautiful

Crimean coast.

See also: CAUCASUS; DECEMBRIST MOVEMENT AND RE-

BELLION; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Rhinelander, Anthony. (1990). Prince Michael Vorontsov:

Viceroy to the Tsar. Montreal: McGill-Queens Uni-

versity Press.

A

NTHONY

R

HINELANDER

VORONTSOV-DASHKOV,

ILLARION IVANOVICH

(1837–1916), viceroy of the Caucasus.

At a moment of great danger to the regime Tsar

Nicholas II appointed his friend and councilor, Illar-

ion Ivanovich Vorontsov-Dashkov, viceroy (namest-

nik) of the Caucasus in 1905. A loyal courtier, Count

Vorontsov-Dashkov faced open rebellion, with most

of western Georgia in the hands of insurgent peas-

ants led by the Marxist Social Democrats. Harsh poli-

cies toward the Armenian Church (in 1903 their

properties had been seized by the government), re-

pression of the workers and peasants, and general

disillusionment with the autocracy as the Russo-

Japanese War went badly, led to the collapse of tsarist

authority south of the Caucasian mountains. The

new viceroy agreed to ameliorate the state’s policies,

return the Armenian church properties, and negoti-

ate with the rebels. The tsar did not approve of these

moderate policies and thought the best place for

rebels was hanging from a tree. “The example would

be beneficial to many,” he wrote. But the viceroy pre-

vailed, using both conciliatory and repressive mea-

sures to pacify the region.

The liberal methods of the viceroy improved

relations among the various nationalities in the

Caucasus. He was thought by many to be pro-

Armenian, and did favor that nationality as it was

well represented in local representative institutions

and possessed great wealth and property. Vorontsov-

Dashkov wrote to the tsar that the government had

itself created the “Armenian problem by carelessly

ignoring the religious and national views of the Ar-

menians.” But he also attempted to placate the

Georgians and the Muslims and permitted educa-

tion in the local languages. By the time Russia went

to war with Turkey in 1915, Armenians formed

volunteer units to fight alongside the Russian army

against the Turks. Although there was resistance

to the draft among Caucasian Muslims, and Geor-

gians were unenthusiastic about the war effort, no

major opposition was expressed. In 1915 Vorontsov-

Dashkov left the Caucasus and was replaced by

Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich. As Vorontsov-

Dashkov departed Tiflis, he was made an honorary

citizen of the city by the Armenian-dominated city

duma, but neither the Georgian nobility nor Azer-

baijani representatives appeared to bid him farewell.

See also: CAUCASUS; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

VORONTSOV-DASHKOV, ILLARION IVANOVICH

1649

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

An engraving of Mikhail Semenovich Vorontsov that appeared

in the

London News.

© M

ARY

E

VANS

P

ICTURE

L

IBRARY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kazemzadeh, Firuz. (1951). The Struggle for Transcauca-

sia (1917–1921). New York: Philosophical Library.

Suny, Ronald Grigor. (1988). The Making of the Georgian

Nation. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

R

ONALD

G

RIGOR

S

UNY

VOROSHILOV, KLIMENT EFREMOVICH

(1881–1969), leading Soviet political and military

figure, member of Stalin’s inner circle.

A machinist’s apprentice who joined the Bol-

sheviks in 1903, Kliment Efremovich Voroshilov

spent nearly a decade underground and in exile,

then emerged in late 1917 to become the commis-

sar of Petrograd. In 1918 he assisted Felix Dz-

erzhinsky in founding the Cheka, then fought on

various civil war fronts, including Tsaritsyn in

1918, where he sided with Josef V. Stalin against

Leon Trotsky over the utilization of former tsarist

officers in the new Red Army. A talented grass-

roots organizer, Voroshilov was adept at assem-

bling ad hoc field units, especially cavalry.

Following the death of Mikhail V. Frunze in late

1925, Voroshilov served until mid-1934 as com-

missar of military and naval affairs, and subse-

quently until May 1940 as defense commissar.

Known more as a political toady than a serious

commander, he served in important command and

advisory capacities during World War II, often with

baleful results. During the postwar era he aided in

the Sovietization of Hungary, but at home was rel-

egated to largely honorific governmental positions.

To his credit Voroshilov objected to using the Red

Army against the peasantry during collectivization,

and, despite complicity in Stalin’s purges, he occa-

sionally intervened to rescue military officers.

Notwithstanding a cavalry bias, he oversaw an im-

pressive campaign for the mechanization of the Red

Army during the 1930s, including support for the

T-34 tank over Stalin’s initial objections. After

Stalin’s death in 1953 Voroshilov was named

chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet,

a post he held until he was forced to resign in 1960

after participating in the anti-Party group opposed

to Nikita Khrushchev.

See also: MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET; STALIN,

JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Erickson, John. (1962). The Soviet High Command. New

York: St. Martin’s Press.

B

RUCE

W. M

ENNING

VOTCHINA

Literally, “patrimony” (the noun derives from

Slavonic otchy, i.e. belonging to one’s father); in

medieval Russia, inherited landed property that

could be legally sold, donated or disposed in an-

other way by the owner (votchinnik).

In the eleventh through thirteenth centuries,

the term mainly indicated the hereditary rights of

princes to their principalities or appanages. Thus,

according to Nestor’s chronicle, the princes who

gathered at Lyubech in 1097 proclaimed: “Let

everybody hold his own patrimony (otchina).” It

was in this sense that Ivan III later applied the word

votchina to all the Russian lands claiming the legacy

of his ancestors, the Kievan princes.

In the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries, as land

transactions became more frequent, the word

votchina acquired a new basic meaning, referring

to estates (villages, arable lands, forests, and so

forth) owned by hereditary right. Up to the end of

fifteenth century, votchina remained the only form

of landed property in Muscovy. The reforms of

Ivan III in the 1480s created another type of own-

ership of land, the pomestie, which made new

landowners (pomeshchiki) entirely dependent on the

grand prince who granted estates to them on con-

dition of loyal service. In the sixteenth century,

Muscovite rulers favored the growth of the po-

mestie system, simultaneously keeping a check on

the circulation of patrimonial estates. Decrees of

1551, 1562, and 1572 regulated conditions under

which alienated patrimonies could be redeemed by

the seller’s kinsfolk. The same legislation stipulated

that each case of donation of one’s patrimony to a

monastery must be sanctioned by the government.

(In 1580, the sale or donation of estates to monas-

teries was totally prohibited.)

Historians have stressed the growing similar-

ity between votchina and pomestie. On the one

hand, as Vladimir Kobrin points out, pomestie from

the very beginning tended to become hereditary

property; on the other hand, the owners of patri-

monies were obliged to serve in the tsarist army

(legally, since 1556), just as pomestie holders did.

VOROSHILOV, KLIMENT EFREMOVICH

1650

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

S. B. Veselovskii cites some cases from the 1580s,

when the authorities ordered the confiscation of

both pomestia (pl.) and votchiny (pl.) of those ser-

vicemen who had ignored the military summons.

But some difference between the two forms of

landed property remained: In the eyes of landown-

ers, votchina preserved its significance as the prefer-

able right to one’s land. As O. A. Shvatchenko put

it, votchiny formed the material basis of the Russ-

ian aristocracy in the sixteenth and seventeenth

centuries.

In spite of governmental regulations and limi-

tations and severe blows of the Oprichnina, the

votchina system survived the sixteenth century,

and after the Time of Troubles experienced new

growth. Beginning with Vasily Shuisky (1610), the

tsars began to remunerate their supporters by

granting them the right to turn part of their po-

mestie estates into votchiny. Thus, new types of

votchina appeared in the seventeenth century. The

Law Code of 1649 also stipulated the possibility of

exchanging pomestie for votchina, or vice versa. Fi-

nally, pomestie and votchina merged during the re-

forms of Peter the Great: specifically, in the 1714

decree on majorats.

See also: GRAND PRINCE; IVAN III; LAW CODE OF 1649;

OPRICHNINA; PETER I; POMESTIE

M

IKHAIL

M. K

ROM

VOTIAKS See UDMURTS.

VOYEVODA

In texts from the era of Kievan Rus, the term

voyevoda designated the commander of a military

host of any significant size, be it an entire field

army, a division, or a regiment. It might also be

used to refer to the administrator or governor of

some territory. Researchers therefore frequently en-

counter the term as a translation of the Greek ar-

chon and satrapis as well as strategos.

By the 1530s, the practice of annually station-

ing regimental commanders (godovye voyevody) on

the Oka River defense line to protect Moscow from

Tatar raids had begun to blur the distinction be-

tween the military command responsibilities of the

regimental commanders and the administrative re-

sponsibility of the vicegerents and fortifications

stewards of the towns: first siege defense, then for-

tifications labor and fiscal administration were

gradually shifted to the former. By the 1560s and

1570s, general fiscal and judicial as well as mili-

tary authority in certain southern and western

frontier districts was entirely in the hands of these

godovye voyevody; the vicegerents and fortifica-

tions stewards were eliminated or subordinated to

them. Godovye voyevody had evolved into town

governors (gorodovye voyevody). During the Time of

Troubles, the breakdown of central chancellery au-

thority left responsibility for mobilizing military

resources and coordinating the struggle against the

Pretenders and foreign interventionists largely up

to the town governors of the upper Volga and

North. The town governor system of local admin-

istration was therefore universalized after the lib-

eration of Moscow and the foundation of the new

Romanov dynasty. By the 1620s most districts

were under a town governor, usually appointed for

two to three years from the lower ranks of the up-

per service class (stolniki, Moscow dvoryane) and

given a working order (nakaz) from the appropri-

ate chancellery.

The town governors had broad responsibilities:

They commanded district garrison forces and de-

fended their districts from attack; they helped

mobilize district military manpower into the regi-

ments of the field army; they supervised fortifica-

tions corvee; they policed and combated banditry;

they investigated and adjudicated civil and crimi-

nal cases and registered deeds; they searched out,

tried, and remanded fugitive peasants; they con-

ducted reviews determining service entitlement

awards, paid out cash and grain service subsidies,

and implemented chancellery instructions to assign

pomestie allotments; they helped surveying and

cadastral inventorying; and they supervised repar-

titions of communal property to reapportion tax

burdens. The quality of their administrative service

was often deficient, however, as they were not ad-

ministrative specialists but notables appointed to

governorships most often as a respite from their

command responsibilities in the field army or their

ceremonial duty at court; governorships were less

likely to give them rank promotions than field

army duty or court duty. They received no special

additional salary for service as governors (even

raises to their regular service subsidies, in recogni-

tion of meritorious service, were rare), and they

therefore sought out their compensation on their

own by soliciting bribes and arranging for com-

munity feeding prestations (kormlenie).

VOYEVODA

1651

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Moscow did develop practices and institutions

to reinforce central chancellery control over the

town governors. The compulsory service ethos and

the precedence (mestnichestvo) system had some re-

straining influence on them; they were usually re-

moved from their posts after their third year,

unless the community petitioned for their reten-

tion; their working orders were made increasingly

specific and comprehensive; and it was general

practice to reduce the range of decisions left to their

discretion so that most of their actions required ex-

plicit preliminary authorization from the chancel-

leries. Over the course of the seventeenth century,

additional control procedures were developed: the

multiplication and refinement of record forms; the

introduction of end-of-term audits; and the orga-

nization of special investigative commissions to re-

spond to community complaints of abuses of

authority.

See also: FRONTIER FORTIFICATIONS; KORMLENIE; LOCAL

GOVERNMENT AND ADMINISTRATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Davies, Brian L. (1987). “The Town Governors in the

Reign of Ivan IV.” Russian History/Histoire Russe 14

(1-4):77–143.

B

RIAN

D

AVIES

VOZNESENSKY, NIKOLAI ALEXEYEVICH

(1903–1950), Soviet economic official who for

many years was close to Stalin.

Born into a foreman’s family near Tula on De-

cember 1, 1903, Nikolai Alexeyevich Voznesensky

was appointed chief of Gosplan, the USSR State

Planning Commission, in January 1938. He sub-

sequently became first deputy prime minister, a

member of Stalin’s war cabinet, and a Politburo

member, and until his arrest in March 1949 re-

mained at the center of Soviet politics and eco-

nomics.

Voznesensky advanced in the Soviet hierarchy

because of his aptitude for economic administra-

tion, his undeviating loyalty to the party line, the

patronage of Leningrad party chief Andrei Zhdanov,

and good luck. He sponsored several measures de-

signed to improve the economic outcome of the

command system, including new monitoring sys-

tems to identify and manage the most acute short-

ages, the realignment of industrial prices with pro-

duction costs, and detailed long-term plans. As a

party loyalist he expertly rationalized each new

turn in official thinking about the economic prin-

ciples of socialism and capitalism. While many

competent and loyal officials were repressed, Voz-

nesensky benefited from Zhdanov’s protection and

had the good fortune to gain high office just as

Stalin’s purges were beginning to taper off.

Voznesensky’s first task was to revive the So-

viet economy, which had been stagnating since

1937. He was still trying when World War II broke

out in 1941. The war exposed the inadequacy of

prewar plans for a war economy, and for a while

the planners lost control. While war production

soared, the civilian sector neared collapse. The vic-

tory at Stalingrad in 1942 and Allied aid made it

possible to restore economic balance in 1943 and

1944. Voznesensky was involved in every aspect

of this story of failure and success.

By the end of the war Voznesensky had be-

come one of Stalin’s favorites. Stalin relied on his

competence, frankness, and personal loyalty. The

same attributes led Voznesensky to fall out with

others, in particular Georgy Malenkov and Lavrenti

Beria. The rivalry was personal; there is no serious

evidence of differences between them on political or

economic philosophy. After Zhdanov’s death in

September 1948, Voznesensky’s good luck ran out.

Malenkov and Beria were soon able to destroy

Stalin’s trust in him. He became ensnared in accu-

sations relating to false economic reports and se-

cret papers that ended in his dismissal, arrest, trial,

and execution. Voznesensky was not the only

prominent figure with connections to Zhdanov to

disappear at this time in what was later known as

the Leningrad affair.

See also: ECONOMIC GROWTH, SOVIET; LENINGRAD AF-

FAIR; STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH; ZHDANOV, AN-

DREI ALEXANDROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gorlizki, Yoram, and Khlevniuk, Oleg. (2004). Cold Peace:

Stalin and the Soviet Ruling Circle, 1945–1953. New

York: Oxford University Press.

Harrison, Mark. (1985). Soviet Planning in Peace and War,

1938–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sutela, Pekka. (1984). Socialism, Planning, and Optimal-

ity: A Study in Soviet Economic Thought. Helsinki: So-

cietas Scientiarum Fennica.

M

ARK

H

ARRISON

VOZNESENSKY, NIKOLAI ALEXEYEVICH

1652

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

VSEVOLOD I

(1030–1093), grand prince of Kiev.

Although Vsevolod was grand prince of Kiev,

son of the eminent Yaroslav Vladimirovich the Wise,

and father of the famous Vladimir Monomakh, his

own career was not outstanding. He was allegedly

Yaroslav’s favorite son and married to a relative of

Byzantine emperor Constantine IX Monomachus.

Before his death in 1054, Yaroslav bequeathed

southern Pereyaslavl to Vsevolod along with terri-

tories in the upper Volga, including Rostov, Suzdal,

and Beloozero. Yaroslav also designated him heir to

Kiev, along with his elder brothers Izyaslav and

Svyatoslav. For some twenty years the three acted

as a triumvirate, asserting their authority over all

the other princes, including their brothers Vyach-

eslav of Smolensk and Igor of Vladimir in Volyn.

As prince of Pereyaslavl, Vsevolod had to defend his

domain against attacks from the nomads, especially

the Polovtsy (Cumans). In 1068 after the latter de-

feated the three brothers, the Kievans forced Izyaslav

to flee to the Poles. Vsevolod joined Svyatoslav in

persuading the citizens to reinstate Izyaslav in Kiev.

In 1072 Vsevolod and his brothers translated the

relics of Saints Boris and Gleb into a new church in

Vyshgorod and together issued the Law Code of

Yaroslav’s Sons (Pravda Yaroslavichey). In 1073,

however, they quarreled, and Vsevolod helped Svy-

atoslav evict Izyaslav from Kiev. After Svyatoslav

died in 1076, Vsevolod succeeded him briefly in Kiev

until Izyaslav reclaimed the throne. In 1078

Izyaslav was killed in battle, and Vsevolod occupied

Kiev, where he ruled until his death. His most dif-

ficult task was to satisfy his many nephews with

territorial allocations. He died on April 13, 1093.

See also: GRAND PRINCE; IZYASLAV I; POLOVTSY; SVY-

ATOSLAV II; VLADIMIR MONOMAKH; YAROSLAV

VLADIMIROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dimnik, Martin. (1994). The Dynasty of Chernigov,

1054–1146. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediae-

val Studies.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

VSEVOLOD III

(1154–1212), Vsevolod Yurevich “Big Nest,” the last

grand prince of Vladimir on the Klyazma to rule

all of Suzdalia, including Rostov and Suzdal.

In 1169 Vsevolod, son of Yury Vladimirovich

“Dolgoruky,” participated in the sack of Kiev orga-

nized by his elder brother Andrei “Bogolyubsky.”

Four years later he ruled Kiev briefly as Andrei’s lieu-

tenant. After his boyars assassinated Andrei in 1174,

his relatives fought for the throne of Vladimir; in

1176, Vsevolod won. He adopted Andrei’s central-

izing policy and stifled all opposition from the neigh-

bouring princes of Murom and Ryazan. He destroyed

Polovtsian camps on the river Don and waged war

against the Volga-Kama Bulgars and the Mordva

tribes to secure the trade route from the Black Sea.

He increased his domains by strengthening the de-

fenses on the middle Volga, building outposts along

the Northern Dvina, seizing towns from Novgorod,

and appropriating its lands along the Upper Volga.

He had limited success, however, in bringing Nov-

gorod itself under his control.

Around 1199, when Vsevolod secured pledges

of loyalty from the Rostislavichi of Smolensk and

the Mstislavichi of Vladimir in Volyn, they recog-

nized him as the senior prince in the dynasty of

Monomakh. The Olgovichi of Chernigov, for their

part, acknowledged his military superiority and

formed marriage alliances with him. In this way

Vsevolod asserted his primacy over the southern

dynasties and the grand prince of Kiev. Before his

death, however, he divided his domain among all

his sons and designated the second eldest Yury his

successor. These actions weakened the power of the

prince of Vladimir. Vsevolod died on April 13, 1212.

See also: BOYAR; GRAND PRINCE; NOVGOROD THE GREAT;

POLOVTSY; YURI VLADIMIROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fennell, John. (1983). The Crisis of Medieval Russia,

1200–1304. London: Longman.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

VYBORG MANIFESTO

The Vyborg Manifesto (“To the People from the Peo-

ple’s Representatives”) was an appeal given by a

group of members of the First State Duma to the

people of Russia, on July 23, 1906, in the city of

Vyborg. It was intended as a sign of protest against

the dissolution of the Duma. After the dissolution

of the Duma, on July 21, 1906, deputies of the

Labor Group (Trudoviks) called for an assembly in

VYBORG MANIFESTO

1653

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

St. Petersburg with the purpose of issuing a man-

ifesto of insubordination to the act of dissolution

and calling for the people to support them. Hold-

ing an assembly in St. Petersburg was impossible,

because both the Duma building and the Cadet

(Constitutional Democrat) Party Club were sur-

rounded by police and military forces. At the propo-

sition of the Cadets, between 220 and 230 Duma

deputies, mostly Cadets and Trudoviks, met in Vy-

borg, Finland, on the eve of July 22. The chairman

was the chairman of the Duma, Sergei Muromtsev.

During the night, the deputies discussed two pos-

sible versions of the manifesto. The first, prepared

by the Trudoviks and the Social Democrats, called

for the army and navy to support the cause of the

revolution and for the people not to follow the or-

ders of the government. The second, prepared by

the Cadets and written by Pavel Milyukov (who was

not a deputy), called for passive resistance: ignor-

ing military service, not paying taxes, and refusal

of state loans unless the Duma approved. The final

draft of the Manifesto, processed by the approval

committee, was close to the Cadets’ version. Despite

the remaining controversies, on July 23 the final

revision of the appeal was signed, because an order

came from St. Petersburg of the dissolution of the

assembly and the danger of “fatal consequences for

Finland.” The Vyborg Manifesto was signed by 180

deputies, later to be joined by 52 more. It was

printed in the form of a leaflet on July 23, 1906,

in Finnish and then Russian in 10,000 copies, and

was reprinted abroad. The reprint of the Vyborg

Manifesto by Russian newspapers was punished

with the confiscation of the press run, and spread-

ing the leaflets was punished with arrests. On July

29, 1906, a court case was started against those

who signed the Manifesto, which called for the na-

tion to oppose the law and the lawful orders of the

government. The Vyborg Manifesto had no signif-

icant impact on the people. In December 1907, the

so-called Vyborg trial was held in St. Petersburg.

At the trial, 167 of the 169 former deputies of the

Duma were sentenced to three months of incarcer-

ation, which meant that they were bereft of the

right to run for position in the Duma and other

civil services.

See also: CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY; DUMA;

REVOLUTION OF 1905

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ascher, Abraham. (1992). The Revolution of 1905: Author-

ity Restored. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Maklakov, V.A. (1964). The First State Duma. Blooming-

ton: Indiana University Press.

O

LEG

B

UDNITSKII

VYSHINSKY, ANDREI YANUARIEVICH

(1883–1955), prosecutor, scholar, diplomat; best

known for conduct of show trials during the Great

Terror.

Andrei Yanuarevich Vyshinsky distinguished

himself as a prosecutor (prosecutor-general of Rus-

sia, 1931–1933; deputy prosecutor general of the

USSR, 1933–1935; prosecutor general of the USSR,

1935–1939); as a scholar (author of authoritative

legal texts, including The Theory of Evidence in

Soviet Law, published in three editions); and as a

diplomat (deputy foreign minister, 1940-1949,

1953–1955; foreign minister and Soviet represen-

tative to the United Nations, 1949–1953). In all of

these roles he displayed unfailing loyalty to his

master and sometime confidant, Josef V. Stalin.

Erudite and a brilliant orator, as skilled in sar-

casm as in logic, the dapper Vyshinsky was trained

as a jurist. He belonged to the Menshevik party be-

fore becoming a Bolshevik in 1920. While work-

ing in educational administration during the 1920s,

Vyshinsky proved his political mettle in perfor-

mances as judge in early show trials (such as

Shakhty). Later, as prosecutor-general, Vyshinsky

continued to develop the political show trial, serv-

ing as prosecutor at the major show trials of 1936

through 1938, at which leading politicians from

the past (e.g., Grigory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev,

Grigory Pyatakov, Nikolai Bukharin, and Alexei

Rykov) were humiliated and forced to confess to

extraordinary acts of betrayal. Archival sources re-

veal that Vyshinsky worked closely with Stalin in

manufacturing the charges and writing the scripts.

Vyshinsky was also a member of the Special Board

of the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs

(NKVD) that during the years 1936 through 1938

processed most of the contrived cases of alleged

saboteurs and counterrevolutionaries.

As Stalin’s prosecutor, Vyshinsky also helped

to restore the authority of law in the post-

collectivization era, eliminate the influence of anti-

law Marxists such as Yevgeny Pashukanis, and de-

velop a jurisprudence that supported the use of

terror against political enemies. Long after leaving

the administration of justice, Vyshinsky remained

VYSHINSKY, ANDREI YANUARIEVICH

1654

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY