Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beissinger, Mark R. (2002). Nationalist Mobilization and

the Collapse of the Soviet State. Cambridge, UK: Cam-

bridge University Press.

Hahn, Gordon M. (2002). Russia’s Revolution from Above,

1985–2000: Reform, Transition, and Revolution in the

Fall of the Soviet Communist Regime. New Brunswick,

NJ, and London: Transaction Publishers.

Solchanyk, Roman. (2001). Ukraine and Russia: The Post

Soviet Transition. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Little-

field.

R

OMAN

S

OLCHANYK

UNITED NATIONS

The United Nations, successor to the League of Na-

tions, was conceived and created by the allies dur-

ing World War II. In 1944 the USSR and the United

States, with other major nations, met at Dumbar-

ton Oaks in Washington, D.C., to plan a postwar

organization that would provide a forum for

the settlement of disputes. Stalin, Roosevelt, and

Churchill solidified plans for the United Nations at

Yalta (1945), compromising on substantive issues

regarding voting procedures, territorial trustee-

ships, and the admission of various countries. In

April 1945 the allies met in San Francisco and wrote

the charter of the new organization, and the United

Nations officially came into existence on October

24, 1945, following the charter’s ratification by the

major powers. All member nations received one

vote in the General Assembly, but the five major

powers enjoyed the right of veto in the Security

Council.

Disputes in the United Nations between the So-

viet Union and the United States paralleled the

growing bitterness of the Cold War. In 1946 the

Soviet Union and the United States clashed over the

issues of Soviet troops in Iran and the control of

atomic weapons. In both cases American victories

led to increasing Soviet disaffection from the inter-

national body. The United States scored another

success in 1950, when a boycott of the Security

Council by Soviet ambassador Yakov Malik over

the seating of China allowed the United States to

win United Nations support for military assistance

for South Korea.

The United Nations remained largely impotent

in the face of a determined superpower. When So-

viet troops moved to crush the Hungarian upris-

ing in 1956, appeals for assistance from the

freedom fighters to the United Nations were ig-

nored. Nevertheless the USSR and the United States

agreed that same year to allow United Nations

monitors into the Middle East to help end the Suez

Crisis. In the fall of 1960 Khrushchev attended the

opening session of the General Assembly and de-

livered a speech attacking the Western powers.

During a reply to the Soviet leader, members of his

delegation hit their fists on the desk in protest;

Khrushchev proceeded to bang the table with his

shoe, creating one of the more memorable images

of the Cold War. In October 1962, when the USSR

denied that it had placed offensive missiles in Cuba,

the United States presented photographic evidence

of the missile sites at the United Nations and con-

vinced world opinion of its position.

The Soviet view of the United Nations slowly

changed over the next two decades, as the emer-

gence of new nations in Africa and Asia shifted the

balance of power in the General Assembly away

from the United States. After seeing the United Na-

tions as an unfriendly body for its first twenty

years of existence, and thereby exercising its right

to veto many United Nations resolutions, the So-

viet Union began to perceive the General Assembly

as a more sympathetic body. Both the USSR and

the United States continued to use the United Na-

tions as a forum for influencing other nations.

Fierce arguments continued over the Middle East,

surrogate wars in Africa, Korean Airline 007, and

other issues.

During the Gorbachev era the USSR sought bet-

ter relations with the West and became more co-

operative at the United Nations. The first major test

of this new policy occurred when Iraq invaded

Kuwait in 1990, and Gorbachev brought Soviet pol-

icy into line with that of the Western powers. Since

that time, Russia has attempted to maintain cor-

dial relations with the United Nations.

See also: COLD WAR; LEAGUE OF NATIONS; UNITED

STATES, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

United States. (1945). United States Statutes at Large

(79th Congress, 1st Session, 1945), 59(2):1033–1064,

1125–1156.

United States. Department of State. (1944). Department

of State Bulletin, vol. 11. Washington, DC: Office of

Public Communication, Bureau of Public Affairs.

United States. Department of State. (1945). Conferences

at Malta and Yalta, 1945 (Foreign Relations of the

UNITED NATIONS

1614

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

United States diplomatic papers 6), 969–984. Wash-

ington, DC: Government Printing Office.

United States. Department of State. (1945). Department

of State Bulletin, vol. 13. Washington, DC: Office of

Public Communication, Bureau of Public Affairs.

H

AROLD

J. G

OLDBERG

UNITED OPPOSITION

Formed in April 1926, the United Opposition was

an alliance between Leon Trotsky, Lev Kamenev, and

Grigory Zinoviev. These former foes headed a loose

association of several thousand anti-Stalinists, in-

cluding remnants of other opposition groups, as

well as Vladimir Lenin’s widow, Nadezhda Krup-

skaya. The United Opposition’s main goal was to

offset support for Josef Stalin among rank-and-file

party members.

In July 1926, United Oppositionists openly

clashed with Stalin at a Central Committee plenum.

Chief among their many complaints was the fail-

ure of state industry to keep pace with economic

development, thus perpetuating a shortage of goods.

They advocated a program of intensified industrial

production and the collectivization of agriculture,

the same program that Stalin would adopt two

years later. The Central Committee responded by

charging Zinoviev with violating the Party’s ban

on factions and removed him from the Politburo.

Thus blocked in the Central Committee, the

United Opposition took its case directly to the fac-

tories by staging public demonstrations in late Sep-

tember. Within a month, under fire from Stalin’s

supporters, Trotsky, Kamenev, and Zinoviev capit-

ulated and publicly recanted. Trotsky was removed

from the Politburo, and Kamenev lost his standing

as a candidate member. Further machinations and

conflicts resulted in the expulsion of the trio from

the Central Committee in October 1927. The fol-

lowing month Trotsky and Zinoviev were purged

from the party altogether, followed by Kamenev’s

removal from the party in December 1927. The de-

feat of the United Opposition set the stage for Stalin

to move against what he labeled the Right Oppo-

sition, thereby consolidating his power.

See also: KAMENEV, LEV BORISOVICH; LEFT OPPOSITION;

STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH; TROTSKY, LEON

DAVIDOVICH; ZINOVIEV, GRIGORY YERSEYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carr, E. H., and Davies, R. W. (1971). Foundations of

a Planned Economy, 1926–1929. 2 vols. New York:

Macmillan.

Deutscher, Isaac. (1963). The Prophet Unarmed: Trotsky,

1921–1929. London: Oxford University Press.

K

ATE

T

RANSCHEL

UNITED STATES, RELATIONS WITH

The history of the interactions between the two

great powers of the last half of the twentieth cen-

tury ranged from a close and mutually beneficial

understanding to intense hostility, yet they never

fought directly against each other. For long peri-

ods, in fact, their experience was one of similar

goals, of respect, and even of adulation, tempered

by periods of fear—the American fear of a threat

to its free and democratic way of life from an “evil

empire,” whether Russian or Communist, and the

Russian fear of encirclement by a superior power

taking advantage of its transitional weaknesses and

vulnerability. The relations of Russia—as an empire,

a Soviet socialist state, or as a fledgling democracy—

with the United States have had a profound impact

upon the history of both countries and on the

whole world. Already in the seventeenth century,

Russian expansion overland through Siberia had

reached the Pacific coast and contact with Asian

powers such as China. Peter the Great, endowed

with great energy and curiosity, commissioned Vi-

tus Bering to explore the waters and determine

whether Asia (Russia’s Siberia) was connected by

land to North America. This drew political and eco-

nomic attention to the region, especially for the

valuable sea otter skins (for exchange with China

for tea), and Russian hunting camps soon appeared

on the Aleutian Islands and along the Alaskan coast

and would result in direct relations with American

colonies settled by Europeans from across the North

Atlantic.

A mutually advantageous and friendly distant

friendship between Russia and the American

colonies began in the 1760s and was based on Russ-

ian hostility toward British supremacy. At the time,

Britain dominated oceanic trade and a huge empire

that included India near the Russian southern

borderland, Britain’s American colonies, and most

of the world’s open water. Both Russia and the

colonies were deeply involved economically in an

Atlantic trade system that brought cargoes of rice,

UNITED STATES, RELATIONS WITH

1615

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

tobacco, sugar, and other products to Russia from

the Americas in exchange for iron products (an-

chors, chains, and nails), coarse linen (sailcloth),

and processed hemp (rope). This direct trade bene-

fited the growing American economy considerably,

especially since it avoided the restrictions of the

British Navigation Acts. Inspired by Catherine the

Great, Russia continued to explore the waters of

the North Pacific, through the voyages of Vitus

Bering and Ivan Chirikov, to discover not only that

America and Asia were separated by water, but

that there existed a large continental land mass just

east of the Russian Empire. Moreover, Russia was

rich in fur-bearing animals that would advance

Russia’s lucrative Siberian fur industry. The British-

Spanish imperial rivalry along the western North

American coast (the Nootka Sound controversy of

1788) instigated a more clearly defined Russian

presence in what would become known as Russian

America, later Alaska.

During the American Revolutionary War, Rus-

sia intervened against Britain with Catherine the

Great’s declaration of Armed Neutrality (1780), a

treaty signed by several European countries that

attempted to protect neutral shipping from Britain’s

high-handed policies at sea, to the benefit of those

North Americans seeking independence. Moreover,

several Russians, most notably Fyodor Karzhavin,

directly assisted the American cause and inspired

an American effort to consolidate a diplomatic

union with Russia with the mission of Francis Dana

(1781). Though nothing came of this, the notion

of a community of interests remained, both polit-

ically and commercially. Direct commerce steadily

increased in the aftermath of the Revolutionary

War, reaching a zenith during the Napoleonic period

of continental blockade and embargo between Britain

and France (1807–1812). During this time full

diplomatic relations were established, with John

Quincy Adams serving as the first American min-

ister in St. Petersburg. This period of diplomatic re-

lations also provided a precedent for a quasi-alliance

between Russia and the United States that would

prevail until late in the nineteenth century. The al-

liance was confirmed by a Treaty of Commerce in

1832 that assured each country of reciprocity in

economic and political relations, and indicated the

importance that each country attached to their mu-

tual interests.

In 1797 the Russian government chartered the

Russian America Company, under the capable

management of Alexander Baranov, to oversee and

develop its barely occupied territories in North

America from headquarters first at Kodiak, then at

Sitka. The main goal was economic: to preserve ac-

cess to the rich sea otter fur sources along the coast

as far south as California. Russia’s fur trade de-

pended especially on New England ship captains,

such as John D’Wolfe of Bristol, Rhode Island, but

it also involved intense, and often hostile, relation-

ships with Native Americans and the establishment

of a costly, distant supply base in Northern Cali-

fornia (Fort Ross) from 1812 to 1841. Russians and

Americans thus very soon became the dominant on

the West Coast of North America; this led Russians

and Americans to refer to “their manifest des-

tinies”—one eastern, the other western.

Mutual economic and political interests con-

tinued through the Crimean War (1854–1856)

with large shipments of cotton, sugar, rice, weapons,

and other American products to Russia. The Amer-

ican import of Russian products slackened, how-

ever, as new sources replaced Russian rope and iron,

and cotton canvas replaced linen sailcloth. Never-

theless, trade between the United States and Russia

in the Pacific expanded through the middle of the

nineteenth century, with American shippers pro-

viding essential services for the distant Russian

UNITED STATES, RELATIONS WITH

1616

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

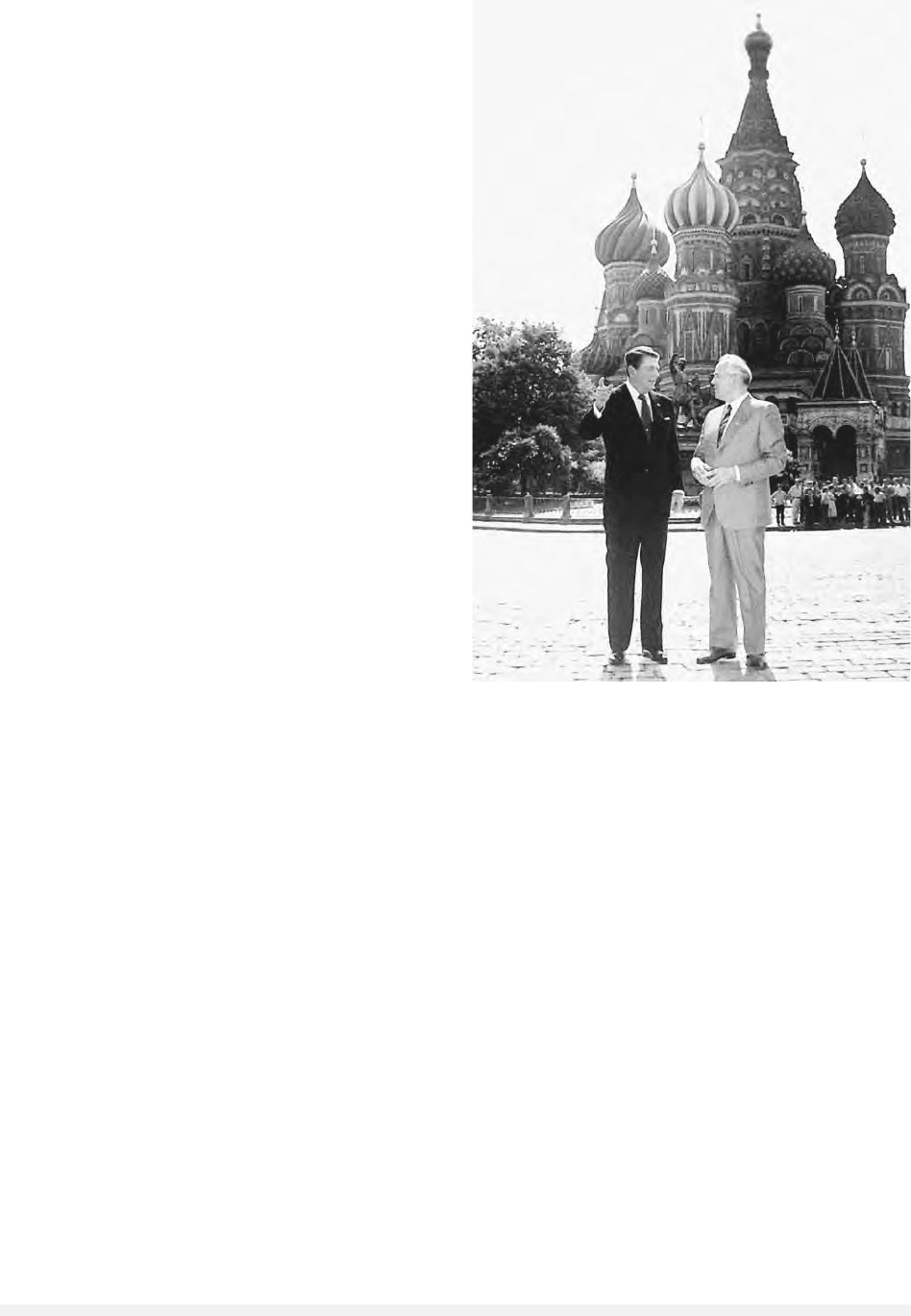

General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev and President Ronald

Reagan greet the White House press corps. W

HITE

H

OUSE

P

HOTOS

/

A

RCHIVE

P

HOTOS

.

bases in Alaska. During the Russian conflict with

France and Britain, the United States provided valu-

able military and other supplies, and more than

thirty Americans served as physicians to the Russ-

ian Army, thus reducing the isolation of Russia and

augmenting the sense of a common interest.

The coincidence of a liberal, reformist govern-

ment in Russia under Alexander II (1856–1881) and

the U.S. Civil War formed an even closer bond, re-

sulting in Russian naval squadrons visiting New

York and San Francisco in 1863 to demonstrate

support for the North. Their presence may have

been influential in restraining France and Britain

from more overt support of the Confederacy, thus

ensuring Union victory. The aftermath witnessed

several much-publicized exchange visits that in-

cluded that of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gus-

tavus Fox to Russia in 1866 and Grand Duke Alexis

hunting buffalo in Nebraska and Colorado with

George Armstrong Custer and William (Buffalo

Bill) Cody in early 1872. These visits may have

marked the peak of the unlikely friendship of au-

tocratic Russia with republican America.

In the cultural arena there were at first rela-

tively few direct contacts, despite a Russian fasci-

nation with the works of James Fenimore Cooper,

Washington Irving, and Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Later in the century, Americans reciprocated with

an appreciation of Ivan Turgenev, Fyodor Dos-

toyevsky, and especially Leo Tolstoy, whose works

produced in America a veritable craze for things

Russian. This was accompanied by renewed Russ-

ian interest in American life as portrayed in stories

of Mark Twain and the art of Frederic Remington,

among others. Russia’s amerikanizm (obsession

with American models for society and technologi-

cal advance) was demonstrated especially by the

adoption of Hiram Berdan’s rifle design for the

Russian army and the considerable Russian pres-

ence at the Chicago World’s Fair (Columbian Ex-

position) in 1893.

American companies, primarily Singer and In-

ternational Harvester, served the Russian quest for

modernization in exchange for monopolistic rights

and independent factories. By 1914 they numbered

among the very largest private concerns in Russia,

employing more than thirty thousand each. New

York Life Insurance Company, dominating that sec-

tor in Russia, was reported to be the largest holder

of Russian stocks. Westinghouse and the Crane

(plumbing) businesses partnered to produce air

brakes for the Trans-Siberian Railroad, launched in

1892. A result was that the manager of the Russ-

ian enterprise, Charles R. Crane, became devoted to

Russian culture and religion and promoted its ap-

preciation in America by sponsoring lectures by the

liberal historian Pavel Milyukov, endowing a chair

at the University of Chicago, and financing tours

of Russian choirs and other artistic groups through

the United States. His advocacy of preserving the

true Russian culture would continue through the

Russian Revolution, civil war, and purges.

By the 1880s two major issues clouded the ear-

lier harmony in relations. One was the Russian ar-

rest and prosecution of political dissenters after the

assassination of Alexander II in 1881 and the re-

sulting Siberian exile system that George Kennan

so eloquently depicted in a series of articles for

American Mercury in the 1880s. This elicited con-

siderable American sympathy for those Russians

UNITED STATES, RELATIONS WITH

1617

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

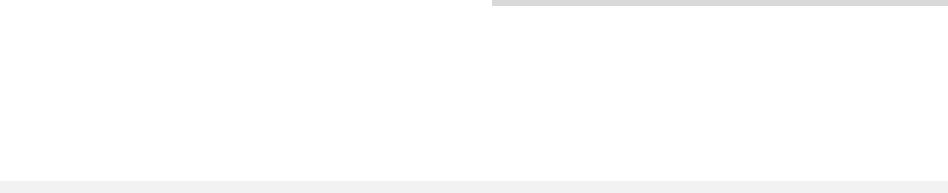

Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev confer during a

walkabout in Red Square, near St. Basil’s Cathedral, May 31,

1998. A

SSOCIATED

P

RESS

. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

who were challenging the autocratic regime for

their democratic and socialist causes and suffering

at the hand of a police state. The other was Russ-

ian policy toward its Jewish population, which re-

quired the Jews to abide by strict limitations on

activities, to emigrate, or to convert to another,

more acceptable religion. Encouraged by American

immigrant Jewish aid societies, many Russian Jews

departed for the United States in the late nineteenth

and early twentieth centuries. These factors not

only produced a generally negative opinion of re-

ligious and political rights in Russia, but also re-

sulted in the abrogation of the Commercial Treaty

of 1832. The agreement had stipulated that Amer-

icans would be assured the same rights in Russia

as Russians, but Russia took this to mean that

American Jews could only have the same restricted

rights as Russian Jews. The Russian effort to alle-

viate the problem by denying entry visas to Amer-

ican Jews on grounds of religion only aggravated

the situation. After considerable debate, the U.S.

Senate formally abrogated the treaty in 1912, but

this had practically no effect on commerce between

the two countries.

In World War I (1914–1918), the United States

and Russia were intimately involved and eventually

on the same side. As one of the initial participants,

Russia suffered a series of defeats. With the cutting

off of regular trade routes through the Black and

Baltic Seas and overland across Europe, Russia faced

severe economic shortages and a breakdown of

transportation. Its relations with the United States

also intensified as Washington agreed under terms

of the Geneva Convention to supervise German,

Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman prisoners of war

in Russia, resulting in a considerable number of ad-

ditional Americans traveling through the country

to inspect the Russian camps. Russia also depended

upon supplies of munitions and transportation

equipment, unfortunately delayed by America’s

own needs and a higher priority for the Western

Front.

The February 1917 Revolution that brought an

end to the Russian autocracy facilitated American

entry into the war “to make the world safe for

democracy.” Large American loans delivered vital

goods to the Russian ports of Vladivostok, Archangel,

and Murmansk. Unfortunately, the steadily dete-

riorating state of rail transport left most of the de-

liveries piled up at the ports. American delegations

came to advise and bolster Russia’s continuation of

the war. One delegation, led by elder statesman

Elihu Root, sought to strengthen the Provisional

Government, first headed by Paul Milyukov and

then by Alexander Kerensky, with a symbolic show

of American support. Railroad, American Red Cross,

and other missions followed, but little could be done

while the Allies placed higher priority on the West-

ern Front. The radical left wing of the revolution

seized power in October, thus dashing American

expectations that Russia was headed down the path

toward representative democracy.

After considering aid to the new Bolshevik-

dominated Soviet government, a policy urged by

American Red Cross mission director Raymond

Robins, the American embassy essentially broke off

direct relations by moving to Vologda at the end

of February 1918, when the Soviet government

moved to Moscow. When the Soviets departed from

the war by signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with

Germany in March, the Allies, hardened by a sense

of Russian betrayal, opted for armed intervention

to prevent the vast arsenal of supplies at ports from

falling into German hands and to assist a consid-

erable anti-Bolshevik resistance in Russia. Reluctant

to participate in intervention, but mindful of Com-

munist-inspired disruptions (the “Red Scare” of

1919), the United States created a massive relief

program (1921–1923) but stipulated that the aid

be administered directly by the American Relief Ad-

ministration.

The American offer and Soviet acceptance were

grounded in humanitarian concerns, but both

Russian and American interests were disappointed

that it did not result in full diplomatic relations.

The United States withheld recognition during the

1920s because of the general American isolation-

ism after the war (and disillusionment with the

peace), concerns about violations of religious

rights, Bolshevik renunciation of imperial debt,

and, more vaguely, a belief that the Soviet Union

did not deserve recognition because of its abuse of

human rights and the Soviet-sponsored Commu-

nist International’s support of the American Com-

munist Party. However, some Americans argued

that Communism could be tempered by contacts,

that much good business could be done, and that

new international developments of the 1930s (the

rise of an aggressive Japan and Germany) required

accommodations. This led to formal diplomatic

recognition (1933) and eventually to the “grand al-

liance” of World War II. The success of the Big

Three (Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin) and their

countries in forging victory in Europe and the Pa-

cific was a major accomplishment of the twentieth

century.

UNITED STATES, RELATIONS WITH

1618

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

That achievement was soon diminished by post-

war conflict. The Red Army’s occupation of a large

part of Central Europe, and the agreements (Yalta

and Potsdam) granting Soviet control of much of

the area, resulted in a line across Europe, designated

by Winston Churchill as the “Iron Curtain.” Insta-

bility across Europe and in the former colonial re-

gions aggravated the divisions and produced a series

of political and military conflicts: the Berlin block-

ade (1948–1949), Communist seizures of power in

Czechoslovakia and Hungary, and the Korean War

(1950–1953). Western Europe, fortunately, was

stabilized by the Marshall Plan (1948) and the es-

tablishment of NATO (1949). The postwar period

was still dominated by a risky and unpredictable

arms race escalating into enormous productions of

nuclear, biological, and other weapons of mass de-

struction. Fortunately, saner heads prevailed on

both sides and resulted in the post-Stalin “spirit of

Camp David” (Khrushchev and Eisenhower summit

meetings). One important result of Khrushchev’s

“peaceful coexistence” was the inauguration of cul-

tural exchanges between the United States and the

Soviet Union in the 1950s that would continue

without interruption and expand.

Unfortunately, additional frictions—the U-2

spy plane incident (1960), building of the Berlin

wall (1961), the Cuban missile crisis (1962), So-

viet suppression of the Czechoslovak “socialism

with a human face” (1968), repression of internal

dissent, the Vietnam War, the Soviet invasion of

Afghanistan (1979), and the Korean Airliner inci-

dent (1983)—kept the Cold War alive into the

1980s. The Brezhnev-era détente, however, had

produced a number of softer, more realistic poli-

cies that led to expanded exchanges, arms limita-

tions talks, additional Soviet-American summit

meetings, and limited emigration of Jews and other

voices of Soviet dissent.

Throughout the Cold War, mutual respect pre-

vailed in regard to cultural and scientific achieve-

ments, creating pressure in both countries for more

communication and efforts at understanding. This

culminated in the Gorbachev-era relaxations of the

once officially closed society. The rewriting of dis-

torted history, the opening of archives, the libera-

tion of Eastern Europe, the unification of Germany,

and, finally, the breakup of the Soviet Union and the

collapse of Communism seemed to herald the end of

the Cold War and the beginning of a new era in So-

viet-American relations. This conclusion, however,

is clouded by an unfinished and indistinct search for

new identity and purpose in both countries.

See also: ALASKA; ALLIED INTERVENTION; ARMS CON-

TROL; COLD WAR; CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS; DÉTENTE;

GRAND ALLIANCE; JEWS; U-2 SPY PLANE INCIDENT;

WORLD WAR I; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, Robert V. (1988). Russia Looks to America: The View

to 1917. Washington, DC: Library of Congress.

Bohlen, Charles E. (1973). Witness to History, 1929–1969.

New York: Norton.

Bolkhovitinov, Nikolai. (1975). The Beginnings of Russian-

American Relations, 1775–1815, tr. Elena Levin. Cam-

bridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dukes, Paul. (2000). The Superpowers: A Short History.

London: Routledge.

Foglesong, David S. (1995). America’s Secret War Against

Bolshevism: U. S. Intervention in the Russian Civil War,

1917–1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Car-

olina Press.

Gaddis, John Lewis. (1978). Russia, the Soviet Union and

the United States: An Interpretive History. New York:

John Wiley and Sons.

Gaddis, John Lewis. (1997). We Now Know: Rethinking

Cold War History. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Hoff Wilson, Joan. (1974). Ideology and Economics: U. S.

Relations with the Soviet Union, 1918–1933. Colum-

bia: University of Missouri Press.

Kennan, George F. (1956, 1958). Soviet-American Rela-

tions, 1917–1920. 2 vols. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press.

Kennan, George F. (1961). Russia and the West under Lenin

and Stalin. Boston: Little, Brown.

LaFeber, Walter. (1997). America, Russia, and the Cold

War, 1945–1996. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Laserson, Max M. (1962). The American Impact on Rus-

sia, 1784–1917: Diplomatic and Ideological. New

York: Collier.

Saul, Norman E. (1991). Distant Friends: The United States

and Russia, 1763–1867. Lawrence: University of

Press Kansas.

Saul, Norman E. (1996). Concord and Conflict: The United

States and Russia, 1867-1914. Lawrence: University

Press of Kansas.

Williams, Robert C. (1980). Russian Art and American

Money, 1900–1940. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Uni-

versity Press.

Williams, William Appleman. (1952). American-Russian

Relations, 1781–1947. New York: Rinehart.

N

ORMAN

E. S

AUL

UNITED STATES, RELATIONS WITH

1619

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

UNITY (MEDVED) PARTY

Boris Yeltsin’s second and final term as president

would expire in June 2000, and he anxiously

searched for a viable successor. In summer 1999 a

serious challenge emerged from two powerful re-

gional leaders, Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov and

Tatarstan president Mintimer Shaimiev. They

merged the two movements they headed, Father-

land and All Russia, into an alliance headed by

Yevgeny Primakov, the prime minister whom

Yeltsin had fired in March. Victory for Father-

land/All Russia in the State Duma election in De-

cember 1999 would give Luzhkov or Primakov a

good chance of defeating the Kremlin’s candidate

for the presidency in June 2000.

In response the presidential staff hastily created

a new loyalist party, Yedinstvo (Unity), also known

as Medved or Bear (from its official name, Interre-

gional Movement “Unity,” whose first letters spell

MeDvEd). Unity was launched in September 1999,

just three months before the election. Unity mobi-

lized the administrative resources of government

ministries and regional governors, thirty-two of

whom backed the new electoral alliance. Unity’s

philosophy was simple: support for Prime Minis-

ter Putin, who was leading the fight against

Chechen bandits. Putin declined to lead Unity; its

official head was the ambitious young minister for

emergency situations, Sergei Shoigu. In 1999 Unity

was helped by oligarch Boris Berezovsky, whose

television station ORT launched relentless personal

attacks on Unity’s rivals, Luzhkov and Primakov.

Ironically, a year later Berezovsky fell out with the

Kremlin and was forced into exile.

Apart from Gennady Zyuganov’s Communist

Party of the Russian Federation, Russian political

parties were exceptionally weak and unstable. Pre-

vious attempts to create a pro-government party,

such as Russia’s Choice (1993) or Our Home is Rus-

sia (1995), had failed. People were willing to vote

for a strong president but voiced their discontent

by voting for opposition parties in parliamentary

elections. About 20 to 30 percent of voters sup-

ported the communists, and a similar number sup-

ported the various democratic parties. Unity hoped

to pull support from across the spectrum, espe-

cially from voters who were skeptical of all ide-

ologies and preferred pragmatic leaders.

Much to everyone’s surprise, Unity did well in

the December 1999 election, winning 23 percent on

the national party list, close behind the Commu-

nists’ 24 percent, and ahead of Fatherland/All Rus-

sia at 13 percent. This cleared the way for Putin’s

successful run for the presidency. Unity then

forged a tactical alliance with the Communists in

parliament, and in 2000 and 2001 the Duma passed

nearly all of Putin’s legislative proposals, from

START II ratification to land reform.

Surveys suggested that Unity was maintain-

ing its electoral support and gaining some influ-

ence in regional elections. In July 2001 Luzhkov’s

Fatherland party, recognizing Unity’s administra-

tive muscle and fearing defeat in the next election,

reluctantly merged with Unity. Shaimiev’s All-

Russia later followed suit. The three parties held a

founding congress to form a new party, called

United Russia, on December 1. The party claimed

to have 200,000 members, but its support seemed

to derive entirely from Putin’s popularity.

In November 2002 legislator Alexander Be-

spalov was replaced as head of United Russia by

Interior Minister Boris Gryzlov, signalling the

Kremlin’s desire to keep tight control over the party

as it prepared for its main test: the December 2003

State Duma elections. A new July 2002 law intro-

duced party list elections for half the seats in re-

gional legislatures, giving Unified Russia a chance

of establishing a presence at a regional level

throughout Russia.

See also: PUTIN, VLADIMIR VLADIMIROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Malyakin, Ilya. (2003). “The ‘United Russia’ Project:

Snatching Defeat from the Jaws of Victory.” Russia

and Eurasia Review 2, No. 5 (March 4). June 20.

<http://www.jamestown.org/pubs/view/rer_002

_005_003.htm >.

P

ETER

R

UTLAND

UNIVERSITIES

In 1725 Peter the Great founded the St. Petersburg

Academy of Sciences, which, unlike its Western

models, included a school of higher education known

as the Academic University. The primary task of the

university was to prepare selected young men to

enter the challenging field of scientific scholarship.

The university encountered difficulties in attract-

ing and retaining students. Because all instructors—

members of the Academy—were foreigners, there

UNITY (MEDVED) PARTY

1620

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

was also a serious language barrier. The general at-

mosphere did not favor the new teaching venture,

and the university folded before the end of the cen-

tury.

After a slow start, Moscow University, founded

in 1755, ended the century as a dynamic enterprise

with a promising future. The initial charter of the

university guaranteed a high degree of academic

autonomy but limited the enrollment to free es-

tates, which excluded a vast majority of the pop-

ulation. In 1855, on the occasion of the centenary

celebration of its existence, the university published

an impressive volume on its scholarly achieve-

ments.

The beginning of the nineteenth century man-

ifested a vibrant national interest in both utilitar-

ian and humanistic sides of science. During the first

decade of the century, the country acquired four

new universities. Dorpat University, actually a

reestablished Protestant institution, immediately

UNIVERSITIES

1621

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Students gather for class at Moscow State University. © M

ICHAEL

N

ICHOLSON

/CORBIS

began to serve as a link to Western universities and

as an effective center for training future Russian

professors. The universities at Kharkov, Kazan, and

St. Petersburg benefited from an initial appoint-

ment of Western professors displaced by the

Napoleonic wars. St. Petersburg University also

benefited from the presence of the Academy of Sci-

ences in the same city.

It was not unusual for the members of the

Academy of Sciences to offer courses at the uni-

versity. Kiev University was founded in 1833 with

the aim of contributing to the creation of a new

Polish nationality favorably disposed toward the

spirit of Russia, a quixotic government plan that

collapsed in a hurry allowing the university to fol-

low the normal course of development.

The 1803 university charter adopted the West-

ern idea of institutional independence and opened

up higher education to all estates. Conservative ad-

ministrators, however, continued to favor the up-

per levels of society. The liberalism and humanism

of government management of higher education

was a passing phenomenon. In the 1820s, the Min-

istry of Public Education, dominated by extreme

conservatism, encouraged animosity toward for-

eign professors and undertook extensive measures

to eliminate the influence of Western materialism

on Russian science. Geology was eliminated from

the university curriculum because it contradicted

scriptural positions.

In a slightly modified form, extreme conser-

vatism continued to dominate the policies of the

Ministry of Public Education during the reign of

Nicholas I (1825–1855). The 1833 university char-

ter vested more authority in superintendents of

school districts—subordinated directly to the Min-

ister of Public Education—than in university rec-

tors and academic councils. Professors’ writings were

subjected to a multilayered censorship system.

Russia’s defeat in the Crimean War in 1855–1856

stimulated rising demands for structural changes

in the nation’s sociopolitical system; in fact, the

Epoch of Great Reforms—as the 1860s were

known—was remembered for the emergence of an

ideology that extolled science as a most sublime

and creative expression of critical thought, the

most promising base for democratic reforms. As

Ivan Petrovich Pavlov, the famed neurophysiolo-

gist, noted, the Nihilist praise for the spirit of sci-

ence as an epitome of critical thought sent young

men in droves to university natural-science de-

partments.

Inspired by the waves of liberal thought and

sentiment, the government treated the universities

as major national assets. Budgetary allocations for

the improvement of research facilities reached new

heights, as did the official determination to send

Russian students to Western universities for ad-

vanced studies. New universities were founded in

Odessa and Warsaw. In 1863 the government en-

acted a new university charter with a solid em-

phasis on academic autonomy.

At the same time, the government abrogated

the more crippling provisions of the censorship law

inherited from the era of Nicholas I. This reform,

however, had a short history: In response to the

Nihilists’ and related groups’ growing criticism of

the autocratic system, the government quickly re-

stored a long list of previous restrictions. This de-

velopment, in turn, intensified student unrest,

making it a historical force of major proportions.

The decades preceding the World War I were filled

with student strikes and rebellions.

The 1884 university charter was the govern-

ment’s answer to continuing student unrest: It pro-

hibited students from holding meetings on

university premises, abolished all student organi-

zations, and subjected student life to thorough reg-

imentation. The professors not only lost their right

to elect university administrators but were ordered

to organize their lectures in accordance with

mandatory specifications issued by the Ministry of

Public Education.

Student unrest kept the professors out of class-

rooms but did not keep them out of the libraries

and laboratories. The waning decades of the tsarist

reign were marked by an abundance of university

contributions to science. Particularly noted was the

pioneering work in aerodynamics, virology, chro-

matography, neurophysiology, soil microbiology,

probability theory in mathematics, mutation the-

ory in biology, and non-Aristotelian logic.

World War I brought so much tranquility to

universities that the Ministry of Public Education

announced the beginning of work on a new char-

ter promising a removal of the more drastic limi-

tations on academic autonomy. The fall of the

tsarist system in early 1917 brought a quick end

to this particular project. During the preceding

twenty years new universities were founded in

Saratov and Tomsk.

The last decades of Imperial Russia showed a

marked growth of institutions of higher education

outside the framework of state universities. To bol-

UNIVERSITIES

1622

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ster the industrialization of the national economy,

the government both improved the existing tech-

nical schools and established new ones at a uni-

versity level. The St. Petersburg Polytechnical

Institute was a major addition to higher education.

There was also a successful effort to establish

Higher Courses for Women financed by private en-

dowments and treated as equal to universities. Sha-

niavsky University in Moscow, established by a

private endowment, presented a major venture in

higher education. In the admission of students, it

was less restrictive than the state universities and

was the first institution to offer such new courses

as sociology.

In 1899 the total enrollment of students in state

universities was 16,497. Forty percent of regular

students sought law degrees, 28 percent chose med-

icine, 27 percent were in the natural sciences, and

only 4 percent chose the social sciences and the hu-

manities. Law was favored because it provided the

best opportunity for government employment.

The February Revolution in 1917 placed the

Russian nation on a track leading to a political life

guided by democratic ideals. The writer Maxim

Gorky greeted the beginning of a new era in na-

tional history in an article published in the popu-

lar journal Priroda (Nature) underscoring the

interdependence of democracy and science. The new

political regime wasted no time in abolishing cen-

sorship in all its multiple manifestations and

granted professors the long-sought right to estab-

lish a national association for the protection of both

science and the scientific community. A govern-

ment decision confirmed the establishment of a

university in Perm.

Immediately after the October Revolution in

1917, the Bolshevik authorities enacted a censor-

ship law that in some respects was more compre-

hensive and penetrating than its tsarist predecessors.

The new government began to expand the national

network of institutions of higher education; in

1981, the country had 835 such institutions, in-

cluding eighty-three universities. The primary task

of universities was to train professional personnel;

scholarly research was relegated to a secondary po-

sition. This policy, however, did not prevent the

country’s leading universities with research tradi-

tions from active scholarship in selected branches

of science. The universities also concentrated on

Marxist indoctrination. The curriculum normally

included such Marxist sciences as historical mate-

rialism, dialectical materialism, dialectical logic, and

Marxist ethics. To be admitted to postgraduate

studies, candidates were expected to pass an exam-

ination in Marxist theory with the highest grade.

Marxist theory was officially granted a status of

science, and Marxist philosophers were considered

members of the scientific community.

In their organization and administration, Soviet

universities followed the rules set up by institutional

charters, specific adaptations to a government-

promulgated model. Faculty councils elected high

administrators, but, according to an unwritten

law, the candidates for these positions needed ap-

proval by political authorities. Local Communist

organizations conducted continuous ideological

campaigns and tracked the political behavior of

professors. In the post-Stalin era political control

and ideological interference lost much of their in-

tensity and effectiveness.

During the last two decades of the Soviet sys-

tem the government encouraged a planned expan-

sion of scientific research in all universities. Selected

universities became pivotal components of the

newly founded scientific centers, aggregates of

provincial research bodies involved primarily in the

study of acute problems of regional economic sig-

nificance. Metropolitan universities expanded and

intensified the work of traditional and newly es-

tablished research institutes. Leading universities

were involved in publishing activity, some on a

large scale. In university publications there was

more emphasis or theoretical than on experimen-

tal studies. Mathematical research, in no need of

laboratory equipment, continued to blossom in

Moscow, Leningrad, and Kiev universities.

See also: ACADEMY OF SCIENCES; EDUCATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kassow, Samuel D. (1961). Students, Professors, and the

State in Tsarist Russia. Berkeley: University of Cali-

fornia Press.

Vucinich, Alexander. (1963–1970). Science in Russian

Culture. 2 vols. Stanford, CA: Stanford University

Press.

A

LEXANDER

V

UCINICH

UNKIAR SKELESSI, TREATY OF

Signed July 8, 1833, between Russia and the Ot-

toman Empire, the Treaty of Unkiar Skelessi re-

flected the interest of Tsar Nicholas I in preserving

UNKIAR SKELESSI, TREATY OF

1623

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY