Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

legitimate authority and the territorial integrity of

existing states in Europe and the Near East.

Nicholas was concerned about the domino effect of

successful revolutions against dynastic states. Un-

able to contain the rebellion of Muhammad Ali in

Egypt, the Ottoman state was threatened by his ad-

vance across Syria and Anatolia in 1832. In re-

sponse, on February 20, 1833, a Russian naval

squadron arrived in Constantinople, followed by

Russian ground forces, with the intent of protect-

ing the Sultan’s capital from the rebels.

The treaty created an eight-year alliance be-

tween Russia and the Ottomans and provided for

Russian aid in the event of an attack against the

Sultan. It reconfirmed the 1829 Treaty of Adri-

anople, which recognized Russian gains in the

Balkans and the Caucasus as well as providing free

access through the Straits for Russian merchant

ships. A secret addendum to the treaty also required

the Ottoman Empire to close the Straits to foreign

warships. Nicholas and his foreign minister, Count

Karl Nesselrode, preferred to see the Straits remain

in Ottoman hands rather than risk the disintegra-

tion of the Ottoman state whereby another Euro-

pean power such as France or Britain might take

control of this strategic waterway.

The treaty appealed to Nicholas’s sense of Rus-

sia as the premier defender of legitimism in post-

Napoleonic Europe. It also confirmed Russian

supremacy in the Black Sea basin and guaranteed

the free passage of Russian commercial vessels into

the Mediterranean, an important point given the

growing importance of Russia’s export trade from

ports such as Odessa.

The treaty was superseded by the Straits Con-

vention of July 13, 1841, when a five-power con-

sortium guaranteed the permanent closure of the

Straits to all warships. Hopes for a more perma-

nent Russo-Ottoman alliance were dashed, how-

ever, when the alliance was not renewed, helping

to lay the groundwork for the Crimean War.

See also: NICHOLAS I; TURKEY, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fuller, William C., Jr. (1992). Strategy and Power in Rus-

sia, 1600–1914. New York: Free Press.

Riasanovsky, Nicholas V. (1984). A History of Russia. Ox-

ford: Oxford University Press.

N

IKOLAS

G

VOSDEV

USHAKOV, SIMON FYODOROVICH

(1626-1686), renowned Russian artist.

Simon Ushakov has been called the last great

master of Russian painting. At the age of twenty-

two (1648) he was appointed court painter and en-

trusted with the state icon painting studios in the

Armory Palace. He not only painted icons, but

made signs, did jewelers’ work, embroidered, and

even designed coins. In addition, he became an ex-

pert on fortifications, mapmaking, and engraving.

As the head of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich Romanov’s

(r. 1645–1676) workshop, he painted several por-

traits of the tsar and the royal family. The tsar had

a profound interest in western European culture

and hired foreign actors and musicians to perform

at court. Western architecture also held the ruler’s

interest, so it is understandable why Ushakov’s

westernized icon style became the most acceptable

form in court circles.

Ushakov became involved in theoretical art dis-

cussions. He wrote “Words to the Lovers of Icons,”

which advanced his views on painting with an em-

phasis on naturalism. The idealization of the saints’

faces in his icons led others to refer to him as a

Slavic Raphael. The colors Ushakov favored in-

cluded rose pink, olive green, pale lilac, occasion-

ally sky blue, and shades of tans and brown.

Western influence can be seen not only in the saints’

lifelike faces but also in the use of classical archi-

tecture, as well as landscapes and scenery borrowed

from German paintings and etchings.

One of themes that Ushakov painted frequently

was the Mandilion (Spas Nerukotvorny or “The Sav-

ior Painted without Use of Human Hands”). Even

though he continued to use egg tempera, rather

than the new oil painting broadly adopted in the

West, he nevertheless abandoned the traditional

two-dimensional, bright-colored style that empha-

sized intense inner spirituality. Instead he prettified

the faces, creating images that in many ways

resembled the Madonnas painted by the Italian Re-

naissance master, Raphael. A mixed style charac-

terizes Ushakov’s work at this time. His style

became the official Orthodox style, copied by many

contemporary Russian icon painters.

Ushakov’s most famous and revolutionary icon

is the Vladimir Mother of God and the Planting and

Spreading of the Tree of the Russian State, painted in

1668. This is a blatantly political icon. A huge rose-

bush symbolizes the Muscovite state; within it is a

USHAKOV, SIMON FYODOROVICH

1624

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

representation of the most venerated icon in Rus-

sia, the Vladimir Mother of God. Christ appears at

the very top, directing his angels to spread his

sheltering cloak. The rosebush springs out of the

Kremlin; Metropolitan Peter and Grand Duke Ivan

Danilovic water it. The tsarist family appears near

the planting, while within the spreading branches

are medallions depicting Russia’s secular and eccle-

siastical princes and her most famous saints.

With his mixed technique Ushakov had a very

strong impact on the development of icon painting

in Russia. Among his pupils who became famous

icon painters were Georgy Zinoviev, Ivan Maxi-

mov, and Mikhail Malyutin. After Ushakov’s time,

the traditional style that had preceded him sur-

vived, but progressive artists adapted his more

Western style up to the twentieth century.

See also: ARCHITECTURE; ICONS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Onasch, Konrad. (1963). Icons. London: Faber and Faber.

Hamilton, George H. (1990). The Art and Architecture of

Russia. London: Penguin Group.

A. D

EAN

M

C

K

ENZIE

USSR See UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS.

USTINOV, DMITRY FEDOROVICH

(1908-1984), marshal of the Soviet Union; Soviet

minister of defense; member of the Politburo, leader

of wartime production in the Soviet Union during

World War II; Hero of the Soviet Union.

Dmitry Ustinov was born in Samara before the

Bolshevik Revolution. In 1922, at the age of four-

teen, he volunteered for service in the Red Army.

In 1923 he was demobilized and attended a poly-

technical institute in Makarev and then began to

work in defense industry. A member of the emerg-

ing Soviet technical intelligentsia, he joined the

Communist Party in 1927, graduated from the

Military Mechanical Institute in 1934, and joined

the Scientific-Technical Institute for Naval Artillery

the same year. In 1937 he began work as a design

engineer at the Bolshevik defense industry complex

in Leningrad and in 1938 became the plant direc-

tor. With the German invasion of the Soviet Union

he was appointed people’s commissar of arma-

ments. In this capacity he played a leading role in

organizing production of Soviet defense industries

and was a leading member of Stalin’s war cabinet,

the State Committee of Defense. In 1944 he was

promoted to the military rank of colonel-general.

In the postwar period Ustinov continued his lead-

ership of Soviet defense industries down to 1957.

He held the posts of deputy chairman of the Coun-

cil Ministers and first deputy chairman of the

Council of Ministers from 1957 to 1965. From

1965 to 1976 he served in the Secretariat of the

Central Committee of the Communist Party, where

he directed the activities of research institutions, de-

sign bureaus, and enterprises. Ustinov was a can-

didate member of the Politburo in 1976 and a Full

Member from 1976 until his death in 1984. In April

1976 he was appointed minister of defense. Dur-

ing his tenure as minister, the Soviet Union began

its ill-fated intervention in Afghanistan.

See also: BREZHNEV, LEONID ILICH; MILITARY, SOVIET AND

POST-SOVIET; STATE DEFENSE COMMITTEE; WAR

ECONOMY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barber, John, and Harrison, Mark. (1999). The Soviet De-

fence-Industry Complex from Stalin to Khrushchev.

London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gelman, Harry. (1984). The Brezhnev Politburo and the De-

cline of Détente. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Spielmann, Karl F. (1978). Analyzing Soviet Strategic Arms

Decisions. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Ustinov, Dmitry. (1983). Serving the Country and the Com-

munist Cause. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

J

ACOB

W. K

IPP

UVAROV, SERGEI SEMENOVICH

(1786-1855), minister of education (1833–1849)

and Academy of Sciences president (1818–1855).

Sergei Uvarov was the longest-tenured and

most influential minister of education and Academy

of Sciences president in Imperial Russian history.

From 1810 to 1821, he also served as superinten-

dent of the St. Petersburg Educational District. In-

deed, Uvarov spent his entire life involved with the

arts and sciences. He published poetry in his teens;

actively participated in the literary quarrels of his

day; authored two dozen essays on literary and

UVAROV, SERGEI SEMENOVICH

1625

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

historical topics; and in retirement, completed the

work for a doctorate in classical studies.

As a statesman, from the 1810s Uvarov acted

upon a certainty that Russia was in its youth and

developing into a West European-style nation. He

was determined, however, that the process of mat-

uration would occur without European-style rev-

olutions and that the educational system would

provide the map for following this special path. He

gave his system a slogan, “Orthodoxy, Autocracy,

Nationality” (Pravoslavie, Samoderzhavie, Narodnost).

This tripartite formula offered a simple, accessible,

patriotic affirmation of native values and an anti-

dote against revolutionary ideas. Devotion to the

Russian Orthodox Church would offset modern

materialism. Autocracy would provide stability

with patriarchal but progressive tsarist leadership.

The concept of nationality promoted an indigenous

attempt to answer the problems of modern devel-

opment, a quest, though, that was to be defined

and guided by the state, not the narod, or people.

Uvarov believed that raising the Russian edu-

cational system to a level of excellence was the sine

qua non for the empire’s progress toward maturity.

He transformed the Academy of Sciences from a

shambles into a world-renowned center of learn-

ing. Uvarov created two first-rate universities, St.

Petersburg (1819) and St. Vladimir’s (1833) and

brought the others to a golden age. He reformed

the gymnasia by introducing the classical curricu-

lum and the study of Russian grammar, history,

and literature. He patronized a new emphasis on

technology and science in education, and he over-

saw the birth of Oriental, Slavic, classical, and

philological studies. For these accomplishments, he

received the title of count in 1846.

While Uvarov’s accomplishments are notable,

his reputation suffered during his lifetime because

of his personal traits, such as greed and arrogance,

and his autocratic handling of his ministry, espe-

cially in the area of censorship. Historians have

tended to dismiss Uvarov as a liberal during the

reign of Alexander I and a reactionary during the

time of Nicholas, ascribing this to his groveling be-

fore the powers-that-be. This interpretation is gain-

said by the fact that he resigned twice, in 1821 and

1849, when tsarist policy turned reactionary and

threatened the aim of educational excellence to

which he had dedicated his life.

See also: EDUCATION; UNIVERSITIES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Riasanovsky, Nicholas V. (1959). Nicholas I and Official

Nationality in Russia, 1825–1855. Berkeley: Univer-

sity of California Press.

Whittaker, Cynthia H. (1984). The Origins of Modern

Russian Education: An Intellectual Biography of Count

Sergei Uvarov, 1786–1855. DeKalb: Northern Illinois

University Press.

C

YNTHIA

H

YLA

W

HITTAKER

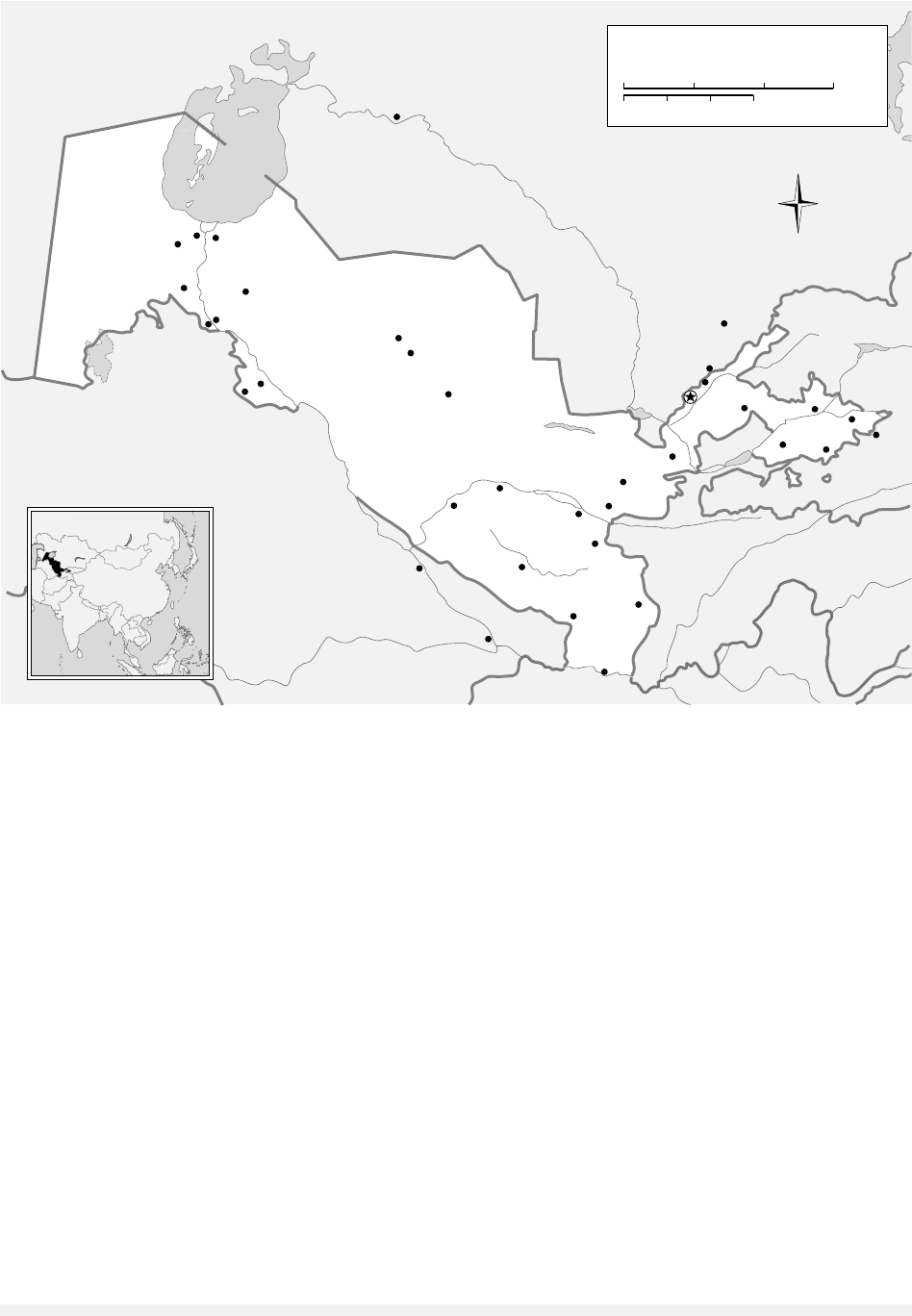

UZBEKISTAN AND UZBEKS

The Uzbeks are a people who settled in the oases

regions of Central Asia more than five hundred

years ago. Early references to Uzbeks suggest that

they were nomadic peoples who lived in the steppes

of what is today Kazakhstan and southern Siberia,

although there is conflicting evidence as to their

origin. Gradually moving southward, they became

a political force in the fifteenth and sixteenth cen-

turies, and were associated with the region be-

tween the great rivers of the Amu Darya and

the Syr Darya. During the early twenty-first cen-

tury, ethnic Uzbeks can be found in Kazakhstan,

the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan,

Afghanistan, as well as smaller communities in

Turkey and China. The majority of Uzbeks live in

the country of Uzbekistan, which is located among

the states noted above in the region between the

Aral Sea to the west and the Tien Shan and Pamir

mountains to the east. Uzbekistan has an area of

447,400 square kilometers (172,700 square miles)

and a population estimated at 25,563,441 people.

Approximately 20,450,000 of these citizens are

ethnic Uzbeks (80%). Significant minorities in

Uzbekistan include Russians (5.5%), Tajiks (5.0%),

Kazakhs (3.0%), Karakalpaks (2.5%), and Tatars

(1.5%). The capital city of Uzbekistan is Tashkent,

which has an estimated population of 2.6 million,

although unofficial counts place the number at

nearly 3.5 million people. Other significant cities

include Samarkand, Bukhara, Andijon, Naman-

gan, and Fergana.

The majority of Uzbeks are Sunni Muslims of

the Hanafi School. Given that several key cities of

Uzbekistan, specifically Bukhara and Samarkand,

were centers of learning in the Islamic world for

centuries, the traditions of that faith are strong in

the country. Even during the Soviet period, when

there were stringent restrictions on Islamic prac-

tices, the religion was practiced in the country.

UZBEKISTAN AND UZBEKS

1626

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Other religions coexist in Uzbekistan and reflect the

ethnic minorities, such as the Russians.

Linguistically, Uzbek is a Turkic language and,

to varying degrees, is mutually intelligible with the

other Turkic languages in the region such as

Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Karakalpak, and Turkmen. Orig-

inally Uzbek was written in the Arabic script. Dur-

ing the Soviet period, this was switched to the Latin

script in the 1920s and later to the Cyrillic script

in 1940. In the post-Soviet period, the Uzbek gov-

ernment decided to return to a Latin script, using

Turkish orthography.

There are significant discussions as to the ori-

gins of the Uzbeks and when they arrived in the

region they occupy today. Indeed, it is accepted that

Tamerlane (Timur the Lame) was an Uzbek and the

first Uzbek unifier of Central Asia. Interestingly,

the Timurid dynasty under Babur (Tamerlane’s

grandson) was defeated by Shaybani Khan, an

Uzbek leader, at the beginning of the sixteenth cen-

tury. Many international historians consider this

event to be the true introduction of Uzbeks to the

region and the first Uzbek state in Central Asia. For

the next four centuries, three main Uzbek states

developed in Central Asia—the Emirate of Bukhara

and the Khanates of Khiva and Kokand. Identity at

this time focused on which city one belonged to,

or more importantly, to one’s faith—Islam. At the

time, these states were not really identified with the

ethnic group of Uzbeks, which was seen as a pop-

ulation more divided by and distinguished among

tribal sub-groupings. Up through the twentieth

century, these states more often used Persian as the

court languages, while Uzbek was used among the

common people.

UZBEKISTAN AND UZBEKS

1627

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

T

u

r

a

n

L

o

w

l

a

n

d

P

e

s

k

i

S

a

m

m

u

K

l

y

z

y

K

Ustyurt

Peski

m

u

g

a

r

a

G

Aral

Sea

Sarykamyshskoye

Ozero

A

m

u

D

a

r

'

y

a

S

y

r

D

a

r

'

y

a

Z

e

r

a

v

s

h

a

n

Q

a

s

h

q

a

d

a

r

y

o

C

h

i

r

c

h

i

q

S

y

r

D

a

r

'

y

a

Tashkent

Shymkent

Samarqand

(Samarkand)

Chärjew

(Chardzhou)

Termez

Muynak

Urga

Kungrad

Nukus

Takhtakupyr

Khodzheyli

Urganch

Uchkuduk

Kulkuduk

Zarafshan

Leninsk

Akkala

Navoi

Derbent

Bukhoro

(Bukhara)

Qarshi

Kerki

Denau

Shakhrisabz

Jizzakh

Guliston

Namangan

Angren

Chirchik

Iskandar

Andijon

Osh

Farghona

Kokand

Bulunghur

Khiva

TURKMENISTAN

TAJIKISTAN

KAZAKHSTAN

KYRGYZSTAN

W

S

N

E

Uzbekistan

UZBEKISTAN

225 Miles

0

0

225 Kilometers

75 150

75 150

Uzbekistan, 1992. © M

ARYLAND

C

ARTOGRAPHICS

. R

EPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

During the 1850s and 1860s the Russian em-

pire began to aggressively seek control over the var-

ious regions of Central Asia. This has often been

couched in terms of the Great Game with the British

Empire, which was a contest for dominance in the

region. In 1865 Russian military forces systemat-

ically took over cities in the Kokand Khanate and

Bukharan Emirate, beginning with the sacking of

Tashkent in that year. By 1876 the Khanate of

Kokand was dissolved and incorporated into the

Governor-Generalship of Turkestan. The Khanate

of Khiva in the west and the Bukharan Emirate

were reduced to the status of protectorates. Dur-

ing the next forty years, this region was part of

the Russian empire. In general, the Russian over-

lords sought to obtain taxes and raw materials

from the region and left the indigenous populations

to their own social and cultural traditions.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Civil

War resulted in radical changes for Central Asia.

Eventually, the region was consolidated under Bol-

shevik rule and new political structures were cre-

ated. The first entity called Uzbekistan appeared in

1924 with the National Delimitation in the Soviet

Union. The Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic actually

included the Tajik Autonomous Republic. This east-

ernmost portion was granted full Union Republic

status in 1929. With modest border adjustments

over the ensuing decades, the Uzbek S.S.R. was con-

sidered to be the homeland for the Uzbeks living in

the Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union collapsed

in 1991, the Uzbek S.S.R. declared its independence

and has henceforth been called the Republic of

Uzbekistan.

For much of the Soviet period, Uzbekistan was

the primary cotton-producing region of the Soviet

Union, with annual quotas exceeding four and five

million metric tons by the 1980s. In addition,

Uzbekistan was a major supplier of gold, strategic

minerals, gas, and agricultural products. In the

post-Soviet period, these commodities remain the

foundation for Uzbekistan’s economy. Uzbekistan

is one of the few states of the former Soviet Union

that did not experience a radical drop in production

and income during the 1990s, largely because of

its reliance on exporting these goods. However, the

country’s economy has not rebounded quickly be-

cause of difficulties in the currency market and the

obstacles faced by foreign investors. Moreover, the

steady increase in population has resulted in a

growing labor force that continues to experience a

high unemployment rate.

Politically, there was also continuity at the time

of independence. In 1991 the president of the Uzbek

S.S.R., Islam Karimov, was elected President of

Uzbekistan. In 1999 and 2000 the militant Islamic

Movement for Uzbekistan (IMU) unsuccessfully at-

tempted to destabilize the country. The government

since considers Islamic extremism to be a major se-

curity concern for the country, whether it is in the

guise of the IMU or the broader, internationally-

based group Hezb-ut Tahrir.

Throughout the 1990s and the early twenty-

first century, Uzbekistan has tried to assert itself

as a leading state in Central Asia. Of great impor-

tance was the desire to reduce the influence of Rus-

sia and remove the notion of an elder brother in the

region. Consequently, Uzbekistan has diplomatic

and economic ties with a number of important

powers, such as China, India, the United States, the

European Union, Turkey, and Iran. Since the events

of September 11, 2001, and the subsequent U.S.

led actions in Afghanistan, Uzbekistan has been

UZBEKISTAN AND UZBEKS

1628

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

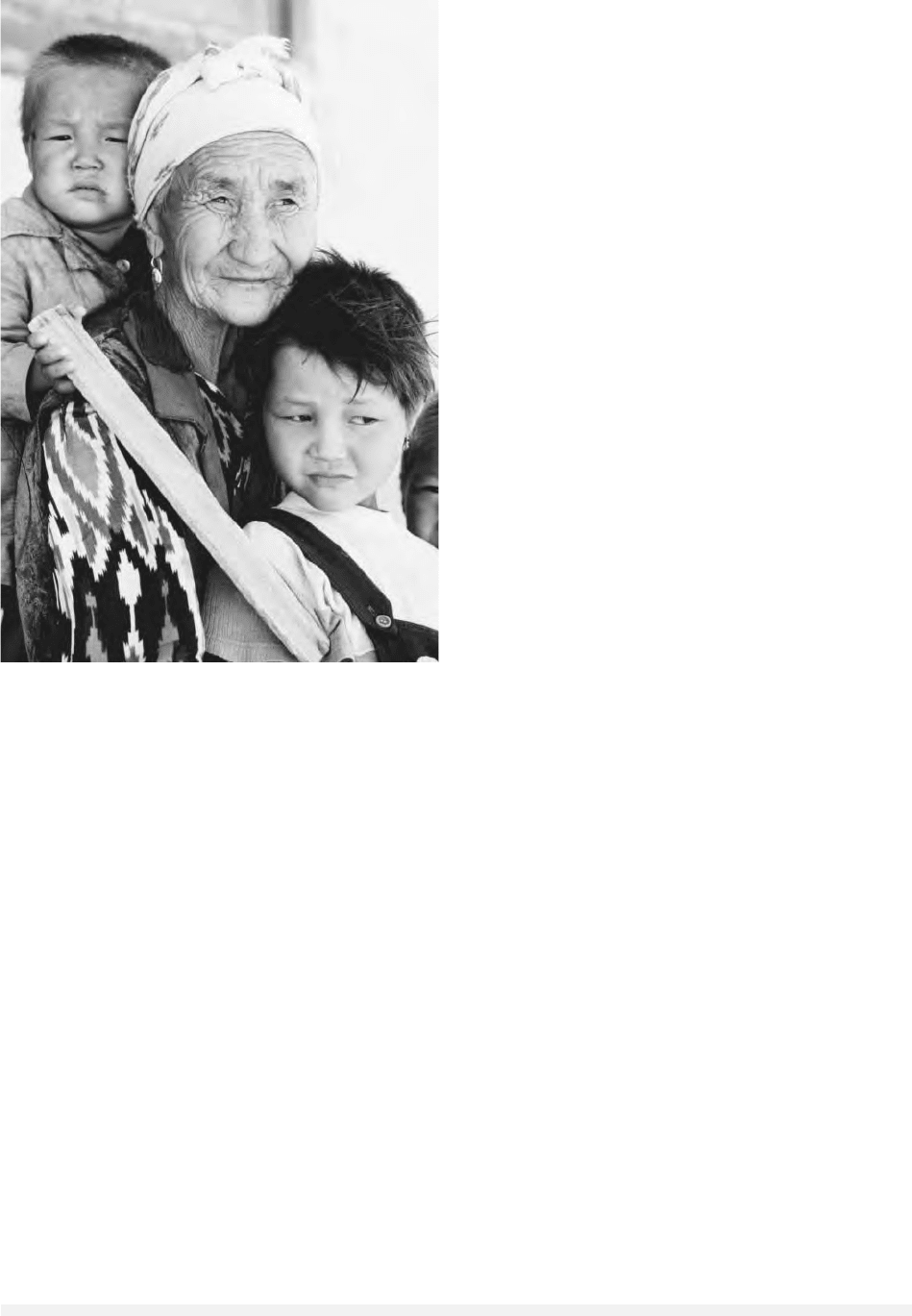

An elderly woman and children in Muyank, Uzbekistan, in

1989. © D

AVID

T

URNLEY

/CORBIS

more active in NATO Partnership for Peace programs

and bilateral security relations with the United

States. Ultimately, Uzbekistan would prefer to see

a greater emphasis on a Central Asian regional se-

curity arrangement, with itself as the key member.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; ISLAM; NATIONALITIES POLICIES,

SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allworth, Edward. (1990). The Modern Uzbeks: From The

Fourteenth Century To The Present: A Cultural History.

Stanford, CA: Hoover University Press.

Babushkin, L. N., ed. (1973). Soviet Uzbekistan. Moscow:

Progress Publishers.

Bohr, Annette. (1998). Uzbekistan: Politics and Foreign

Policy. London: RIIA.

Gleason, Gregory. (1997). The Central Asian States: Dis-

covering Independence. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Kangas, Roger. (2002). Uzbekistan in the Twentieth Cen-

tury: Political Development and the Evolution of Power.

New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Karimov, Islam. (1997). Uzbekistan on the Threshold of the

Twenty-First Century. Surrey, UK: Curzon Press.

Levitin, Leonid, with Carlisle, Donald S. (1995). Islam Ka-

rimov: President of the New Uzbekistan. Vienna: Agrotec.

MacLeod, Calum, and Mayhew, Bradley. (1999). Uzbek-

istan: The Golden Road to Samarkand. London: Odyssey.

Melvin, Neil. (2000). Uzbekistan: Transition to Authori-

tarianism on the Silk Road. Amsterdam: Harwood

Academic Publishers.

R

OGER

K

ANGAS

UZBEKISTAN AND UZBEKS

1629

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

VALUE SUBTRACTION

Value subtraction, or negative value added, occurs

when resources and other inputs used in the pro-

duction process generate output with a lower value

than that of the original resources and inputs. The

management of Soviet state-owned enterprises, fo-

cusing on fulfilling plan targets in order to receive

a bonus, tended to fulfill the main plan target,

quantity of output, with little regard for cost or

efficiency considerations. At the same time, enter-

prises faced centrally determined prices for both

the input used and the output produced. Soviet

centrally determined prices were not based upon

supply and demand conditions in either the do-

mestic or global market, nor were they adjusted in

response to obvious surplus or shortage condi-

tions. Consequently, neither the prices nor the cor-

responding profits or losses generated in the

planning process provided meaningful information

to Soviet firms in terms of whether to expand or

contract their operations. The primary obligation

of each firm was to fulfill annual output plan

targets.

Value subtraction characterized the operation

and performance of Soviet firms when their inputs

and output were valued at world market prices.

World market prices were more accurate reflections

of the economic cost of producing an item than So-

viet centrally determined prices, because they in-

corporated marginal rather than average costs of

production, and because they adjusted to surplus

and shortage conditions generated by ever-changing

actions of buyers and sellers. Typically, Soviet

prices were well below world market prices for the

majority of resources and other inputs used in the

production process. Consequently, when world

market prices were applied by Western researchers

and analysts to the actual resources and inputs

used in the Soviet production process, the newly

calculated costs of production were much higher.

These higher costs were not offset by applying

world market prices to the produced output, how-

ever, because the technological level of Soviet en-

terprises and abject quality assessments kept Soviet

output valuations low in comparison to world

standards. The existence of value subtraction, or

negative value added, was confirmed by Soviet

economists and analysts when glasnost and pere-

stroika in the late 1980s allowed more frank and

detailed discussions of actual conditions in the So-

viet economy.

V

1631

See also: HARD BUDGET CONSTRAINTS; RATCHET EFFECT;

VIRTUAL ECONOMY

S

USAN

J. L

INZ

VARANGIAN See VIKINGS.

VARENNIKOV, VALENTIN IVANOVICH

(b.1923), commander-in-chief of the Soviet Ground

Forces; deputy minister of defense; General of the

Army; Hero of the Soviet Union; member of the

State Duma.

Valentin Krasnodar was born on December 13,

1923, in Krasnodar in the Kuban region of South

Russia. He joined the Red Army in 1941 as an of-

ficer cadet and was commissioned in 1942. He took

part in the defense of Stalingrad as an artillery of-

ficer and served in that capacity through the war

to the assault on Berlin. Varennikov was a stand-

bearer at the Victory Parade in Red Square in 1945.

After the war he commanded artillery and infantry

units. In 1954 he graduated from the Frunze Mil-

itary Academy.

Varennikov advanced in the army leadership

and graduated from the Voroshilov Military Acad-

emy of the General Staff in 1967. During the late

1960s and early 1970s he commanded an army

and served as deputy commander of the Soviet

Group of Forces in Germany and as commander of

the Carpathian Military District. In 1979 he was

head of the Operations Directorate of the General

Staff, which planned the military intervention in

Afghanistan. In 1984 he assumed the post of

deputy chief of the Soviet General Staff with re-

sponsibility for direct oversight of operations in

Afghanistan; he later oversaw the withdrawal of

Soviet forces.

In January 1989 Varennikov was made com-

mandor of Soviet Ground Forces. In August 1991

he was an active participant in the conspiracy to

remove Mikhail Gorbachev and prevent the procla-

mation of a new union treaty. During the at-

tempted coup Varennikov was in Kiev. Arrested and

jailed when the coup collapsed, Varennikov refused

to accept an amnesty when it was offered in March

1994. Later that year, the Military Collegium of

the Supreme Court ruled that he was not guilty of

treason. In December 1995 he ran for election to

the State Duma as a candidate from the Commu-

nist Party and won. He won re-election in 2000

and serves as chairman of the parliamentary Com-

mittee on Veterans’ Affairs.

See also: AUGUST 1991 PUTSCH; MILITARY, SOVIET AND

POST-SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gorbachev, Mikhail. (1991). The August Coup: The Truth

and the Lessons. New York: Harper Collins.

Kipp, Jacob W. (1989). “A Biographical Sketch on Gen-

eral of the Army Valentin Ivanovich Varennikov.”

Ft. Leavenworth, KS: Foreign Military Studies Office.

Odom, William E. (1998). The Collapse of the Soviet Mil-

itary. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

J

ACOB

W. K

IPP

VARGA, EUGENE SAMUILOVICH

(1879–1964), major figure in the Soviet econom-

ics establishment and expert on the world capital-

ist system who fell afoul of Stalinist dogma.

Eugene Varga was educated at the universities

of Paris, Berlin, and Budapest, receiving a doctoral

degree from the last in 1909. He joined the Hun-

garian Social Democratic Party in 1906 and was a

writer and editor on economic matters for its cen-

tral organ. When the communists came to power

in Hungary in 1919, he served as commissar of fi-

nance and then as chairman of the Supreme Coun-

cil of the National Economy. After the regime fell

he moved to the USSR.

Varga’s specialty was capitalist political econ-

omy and economic conditions in the capitalist

world, on which he was an influential and au-

thoritative spokesman during the interwar period.

He was elected a full member of the Soviet Acad-

emy of Sciences in 1939 and was director of its In-

stitute of World Economics and Politics until 1947,

when the institute was shut down because of the

views he expounded in Changes in the Capitalist

Economy as a Result of the Second World War. Varga

defended himself vigorously at a conference of

economists held to attack him, but was forced to

recant. In the post-Stalin period Varga was ulti-

mately restored to a position of honor, and in 1959

his eightieth birthday was celebrated as a notable

jubilee presided over by Academician Konstantin

Ostrovitianov, who had orchestrated the attack on

him in 1947. In 1963 he was awarded the Lenin

VARANGIAN

1632

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Prize for “scientific treatment of the problems of

modern capitalism.”

Despite his independence in analyzing economic

developments in the capitalist world, and his

courage in fighting Stalinist dogmatism, Varga was

a thoroughly orthodox Marxist, and a critic of the

ideas of Soviet econometricians and mathematical

economists.

See also: MARXISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Domar, Evsey. (1950). “The Varga Controversy.” Amer-

ican Economic Review 40:132–151.

R

OBERT

W. C

AMPBELL

VASILEVSKY, ALEXANDER MIKHAILOVICH

(1895–1977), Soviet military hero of World War II.

A member of the Communist Party from 1938,

Alexander Mikhailovich Vasilevsky was born in the

village of Novo-Pokrovka, now Ivanovo Oblast. He

graduated from military school in 1914. He served

as a junior officer in the tsarist army during World

War I. From 1918 to 1931 he commanded a com-

pany, then a battalion, then an infantry regiment

in the Red Army. From 1931 to 1936 Vasilevsky

held executive posts in combat training organs

within the People’s Commissariat of Defense and

Volga Military District. From 1937 to 1941 he

served on the General Staff, from 1941 to 1942 as

deputy chief, and from 1942 to 1945 (during

World War II or the Great Patriotic War) as Chief

of the General Staff of the Soviet Armed Forces and

concurrently, deputy people’s commissar of de-

fense of the USSR.

Upon instructions from the Supreme Com-

mand Headquarters, Vasilevsky helped to elaborate

many major strategic plans. In particular,

Vasilevsky was among the architects (and partici-

pants) of the 1943 Stalingrad offensive. He coordi-

nated actions of several fronts in the Battle of Kursk

and the Belorussian and Eastern-Prussian offensive

operations. Under Vasilevsky’s leadership, a strate-

gic operation aimed at routing the Japanese Kwan-

tung army was successfully carried out between

August and September of 1945.

Increasingly, after the German invasion of June

1941, officers with world-class military skills, who

either emerged unscathed by Stalin’s purges or

were retrieved from Stalin’s prisons and camps,

came to the fore. Vasilevsky was among these men.

Although Stalin was loath to trust anyone fully,

this innate distrust did not prevent him from tap-

ping the resources of his most talented military

strategists during World War II. In the first year

of the war, when the USSR was on the defensive,

Stalin often made unilateral decisions. However, by

the second year, he depended increasingly on his

subordinates. As Marshal Vasilevsky has recalled,

He came to have a different attitude toward

the General Staff apparatus and front com-

manders. He was forced to rely constantly on

the collective experience of the military. Before

deciding on an operational question, Stalin lis-

tened to advice and discussed it with his deputy

[Zhukov], with leading officers of the General

Staff, with the main directorates of the People’s

Commissariat of Defense, with the commanders

of the fronts, and also with the executives in

charge of defense production.

His most astute generals, Vasilevsky and Georgy

Zhukov included, learned how to nudge Stalin to-

ward a decision without talking back to him.

While serving as a member of the Central Com-

mittee of the Soviet Communist Party between

1952 and 1961, Vasilevsky also held the post of

first deputy minister of defense from 1953 to 1957.

Twice named Hero of the Soviet Union, he was also

twice awarded the military honor, the Order of Vic-

tory, and was presented with many other orders,

medals, and ceremonial weapons. He retired the fol-

lowing year and died fifteen years later.

See also: MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET; WORLD

WAR I; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beevor, Antony. (1999). Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege,

1942–1943. New York: Penguin Books.

Colton, Timothy. (1990). Soldiers and the Soviet State.

Princeton: Princeton University Press.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

VAVILOV, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH

(1887–1943), internationally famous biologist.

Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov achieved international

fame as a plant scientist, geographer, and geneti-

cist before he was arrested and sentenced to death

VAVILOV, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH

1633

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

on false charges of espionage in 1940. Born into

a wealthy merchant family in pre-revolutionary

Russia, Vavilov was renowned for his personal

charm, integrity, and international scientific pres-

tige. He graduated from the Moscow Agricultural

Institute in 1911, continued his studies of genetics

and horticulture in Europe the following year, and

in 1916 led an expedition to Iran and the Pamir

Mountains to search for ancestral forms of mod-

ern agricultural plant species. “The Law of Ho-

mologous Series in Hereditary Variation,” his first

major theoretical contribution, published in Russia

in 1920 and then in the Journal of Genetics, argued

that related species can be expected to vary genet-

ically in similar ways.

Vavilov spoke many languages and traveled ex-

tensively throughout the United States and Europe

to meet with colleagues and study scientific inno-

vations in agriculture. He is best known for The

Centers of Origin of Cultivated Plants (1926), in

which he established that the greatest genetic di-

versity of wild plant species would be found near

the origins of modern cultivated species. Until 1935

he organized expeditions to remote corners of the

world in order to collect, catalog, and preserve spec-

imens of plant biodiversity. In the Soviet Union

Vavilov was a powerful advocate and organizer of

scientific institutions, and he tirelessly promoted

research in genetics and plant breeding as a means

of improving Soviet agriculture. Vavilov was direc-

tor of the Institute of Applied Botany (1924–1929),

a member of the USSR Academy of Sciences, direc-

tor of the All-Union Institute of Plant Breeding

(1930–1940) and the Institute of Genetics

(1933–1940), president and vice-president of the

Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences

(1929–1938), and president of the All-Union Geo-

graphical Society (1931–1940).

Vavilov’s increasingly vocal and uncompro-

mising opposition to the falsification of genetic sci-

ence propagated by Trofim Lysenko and his

followers culminated in his arrest in 1940. His

death sentence was commuted to a twenty-year

prison term in 1942; he died of malnutrition in a

Saratov prison one year later. Vavilov is considered

a founding father in contemporary studies of plant

biodiversity. He left an important legacy as one of

the great Russian scientific and intellectual figures

of the early twentieth century.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Graham, Loren R. (1993). Science in Russia and the Soviet

Union. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Krementsov, Nikolai. (1997). Stalinist Science. Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press.

Popovskii, Mark Aleksandrovich. (1984). The Vavilov Af-

fair. Hamdon, CT: Archon Books.

Y

VONNE

H

OWELL

VECHE

The veche was a popular assembly in medieval Russ-

ian towns from the tenth to the sixteenth centuries.

Veches became particularly active at the turn of the

twelfth century, before falling into decline except

in the towns of Novgorod, Pskov, and Viatka. At

times, the veche in Novgorod participated in se-

lecting or dismissing the posadniks (mayors) and

tysiatskiis (thousandmen). Originally, one tysiatskii

was head of the town militia but over time, sev-

eral were chosen and became judicial and civil of-

ficials. The veche also chose the archbishop, and the

heads of the major monasteries. It also tried cases,

ratified treaties, and addressed other public matters.

Meetings sometimes turned violent. In Imperial and

Soviet historiography, the veche was often used as

an example to demonstrate whether Russia had any

democratic tradition or had always been autocratic.

The veche remains an enigmatic phenomenon.

The word is rooted in the words ve and veshchati,

the latter meaning: to pontificate, play the oracle,

or to lay down the law. However, medieval chron-

iclers used the term not only to mean popular as-

semblies, but also to speak of crowds or mobs.

Primary sources are often silent as to the origin or

demise of the veche, the scope of its authority, its

specific membership, or the rules and procedures

governing its activities.

Primary sources indicate that, at least in the

cities of Novgorod and Pskov, the veche may have

had a broad social base. In the case of the veche

that confirmed the Novgorod Judicial Charter in

1471, its members included the Archbishop-elect,

the posadniks, the tysiatskiis, the boyars, the zhi-

tye liudi (the ranking or middle class citizens), the

merchants, the chernye liudi (lit. black men, refer-

ring to the lower class or tax-paying citizens), and

“all the five ends (boroughs), and all Sovereign

Novgorod the Great.” Other documents show

veches of narrower membership. For example, a

1439 treaty signed between Novgorod and the

Livonian city of Kolyvan (Tallinn) lists only the

posadniks and tysiatskiis as being members of the

veche. A commercial document signed the same

VECHE

1634

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY