Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

cathedrals are of approximately the same height.

Therein lies an explanation for the much sharper

sense of vertical development in the Novgorod

cathedral.

Novgorod chronicles indicate that the interior

was painted with frescoes over a period of several

decades. Fragments of eleventh–century work have

been uncovered, as well as early twelfth–century

frescoes. Most of the original painting of the inte-

rior has long since vanished under centuries of ren-

ovations. Although small areas of the interior had

mosaic decorations, there were no mosaics compa-

rable to those in Kiev. The exterior facade above the

west portal also displays frescoes, but the most dis-

tinctive element is the portal itself, with its magnif-

icent bronze Sigtuna Doors, produced in Magdeburg

in the 1050s and taken from the Varangian fortress

of Sigtuna by Novgorod raiders in 1117.

See also: ARCHITECTURE; CATHEDRAL OF ST. SOPHIA, KIEV;

NOVGOROD THE GREAT; VLADIMIR YAROSLAVICH;

YAROSLAV VLADIMIROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brumfield, William Craft. (1993). A History of Russian

Architecture. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rappoport, Alexander P. (1995). Building the Churches of

Kievan Russia. Brookfield, VT: Variorum.

W

ILLIAM

C

RAFT

B

RUMFIELD

CATHEDRAL OF THE ARCHANGEL

The Cathedral of the Archangel Mikhail, in the

Moscow Kremlin, served as the mausoleum of the

Muscovite grand princes and tsars until the end of

the seventeenth century. The present building (built

1505–1509) was commissioned by Tsar Ivan III

(reigned 1462–1505) to replace a fourteenth-cen-

tury church. The architect was Alvise Lamberti de

Montagnano, an Italian sculptor from Venice,

known in Russia as Alevizo the New. His design

combined a traditional Russian Orthodox five-

domed structure with Renaissance decorative fea-

tures such as pilasters with Corinthian capitals and

scallop-shell motifs, which influenced later Russian

architects. The cathedral contains the tombs of

most of the Muscovite grand princes and tsars from

Ivan I (reigned 1325–1341) to Ivan V (reigned

1682–1696), forty-six in all. In addition, shrines

contain the relics of St. Dmitry (son of Ivan IV, died

1591) and St. Mikhail of Chernigov (d. 1246). Ivan

IV (r. 1533–1584) is buried behind the iconostasis.

The present bronze casings were added to the

seventeenth-century sarcophagi in 1906. The fres-

coes on walls, ceilings, and pillars, mainly dating

from the mid-seventeenth century, include iconic

images of Russian princes and tsars and relate the

military exploits of the warrior Archangel Mikhail,

keeper of the gates of heaven. His icon was com-

missioned to celebrate the Russian victory at Ku-

likovo Pole in 1380. The cycle celebrates Moscow’s

rulers as successors to the kings of Israel, as God’s

representatives fighting evil on earth, and as patrons

of Russia’s ruling dynasty in heaven.

From the 1720s onward, Peter I’s Cathedral of

Saints Peter and Paul in St. Petersburg became the

new imperial mausoleum. Of the later Romanovs,

only Peter II (r. 1727–1730) was buried in the

Cathedral of the Archangel. However, the imperial

family continued to pay their respects at their an-

cestors’ tombs after coronations and on other ma-

jor state occasions.

See also: ARCHITECTURE; CATHEDRAL OF ST. BASIL;

CATHEDRAL OF THE DORMITION; KREMLIN.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brumfield, William. (1993). A History of Russian Archi-

tecture. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

L

INDSEY

H

UGHES

CATHEDRAL OF THE DORMITION

The first Kremlin Dormition cathedral, a simple one-

domed masonry structure, was built by Prince Ivan

I Danilovich of Moscow in 1327 as the seat of the

head of the Russian Orthodox church, Metropolitan

Peter. In 1472 Metropolitan Filipp of Moscow de-

cided to replace the old church, laying the founda-

tion stone with Grand Prince Ivan III (r. 1462–1505),

but in 1474 the new building was destroyed by an

earth tremor before it was completed. Ivan then

hired the Italian architect Aristotele Fioravanti, or-

dering him to model his church on the thirteenth-

century Dormition cathedral in Vladimir, in the

belief that the prototype was designed by Mary

CATHEDRAL OF THE DORMITION

203

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

herself. Fioravanti took the traditional five-domed

structure, rounded bays, and decorative arcading,

but added Renaissance proportions and engineering,

“according to his own cunning skill,” as a chronicle

related, “not in the manner of Muscovite builders.”

The church became the model for a number of other

important cathedral and monastery churches, for

example in the Novodevichy convent and the Trin-

ity-St. Sergius monastery.

The first frescoes were painted in 1481 to 1515

and restored several times “in the old manner” in

the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. The com-

plex cycles allude to the unity of the Russian land,

the celebration of its saints and the history of the

cathedral itself, as well as the life and veneration

of Christ and the Mother of God. The icons on the

lower tier of the iconostasis (altar screen), the most

famous of which was the twelfth-century Byzan-

tine “Vladimir” icon of the Mother of God, also re-

ferred to the gathering of the Russian lands and the

transfer of sacred authority to Moscow from

Jerusalem, Byzantium, and Kiev, as did the so-

called Throne of Monomachus, made for Ivan IV

in 1551, the carvings on which depict scenes of the

Byzantine emperor Constantine IX Monomachus

presenting imperial regalia to Prince Vladimir of

Kiev (1113–1125).

In February 1498 the cathedral saw Ivan III’s

grandson Dmitry crowned as heir. From 1547,

when Ivan IV was crowned there, it was the venue

for the coronations of all the Russian tsars and,

from the eighteenth century, the emperors and

empresses. It also saw the investitures and most

of the burials of the metropolitans and patriarchs,

up to and including the last patriarch Adrian (died

1700). Major repair work followed damage caused

by the Poles in 1612 and Napoleon’s men in 1812.

The cathedral was particularly revered by Nicholas

II, in preparation for whose coronation in 1896 a

major restoration was carried out. Late tsarist of-

ficial guides to the cathedral underlined the belief

that the formation of the Russian Empire was

sanctioned by God and symbolized in the cathe-

dral’s history and its holy objects (e.g. a piece of

the robe of Our Lord and a nail from the Cross).

In Soviet times it became a museum, but since the

1990s it has been used intermittently for impor-

tant services.

See also: IVAN I; IVAN III; IVAN IV; NICHOLAS II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berton, Kathleen. (1977). Moscow: An Architectural His-

tory. London: Studio Vista.

Brumfield, William. (1993). A History of Russian Archi-

tecture. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

L

INDSEY

H

UGHES

CATHERINE I

(c. 1686–1727) Yekaterina Akexeyevna, born

Martha Skavronska(ya), the second wife of Peter I

and empress of Russia from February 8, 1725 to

May 17, 1727.

Martha Skavronskaya’s background, national-

ity, and original religious affiliation are still subject

to debate. She encountered the Russian army in

Livonia in the summer of 1702, when she was

working as a servant, and apparently became the

mistress first of a field marshal, then of Peter I’s fa-

vorite, Alexander Menshikov, then of Peter himself.

By 1704 she was an established fixture in the royal

entourage. There were unconfirmed rumors of a se-

cret marriage in 1707, but only in 1711, prior to

his departure for war against Turkey, did Peter

make Catherine his consort. Their public wedding

took place in February 1712 in St. Petersburg. The

marriage was deplored by traditionalists, because

Peter’s first wife was still alive and Catherine was

a foreigner. It is unclear precisely when she con-

verted to Orthodoxy and took the name Catherine.

Catherine established her own patronage net-

works at court, where she was closely allied with

Menshikov, arranging the marriages of elite

women, interceding with Peter on behalf of peti-

tioners, and dispensing charity. Peter provided her

with a western-style court and in 1714 introduced

the Order of St. Catherine for distinguished women

and made her the first recipient, in recognition of

her courage at the Battle of Pruth in 1711. In May

1724, in a lavish ceremony in the Moscow Krem-

lin, he crowned her as his consort. In November,

however, relations were soured by the arrest and

execution of Catherine’s chamberlain Willem Mons

on charges of corruption, who was also reputed to

be her lover. Despite issuing a new Law on Suc-

cession (1722), Peter died in 1725 without naming

a successor. It suited many leading men to assume

that Catherine would have been his choice. Her sup-

porters argued that not only would she rule in Pe-

ter’s spirit, but she had actually been “created” by

him. She was the all-loving Mother, caring for or-

phaned Russia. Such rhetoric won the support of

the guards.

CATHERINE I

204

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Catherine’s was a remarkable success story.

Not only did she manage, with Peter’s help, to in-

vent a new identity as empress-consort, but her

short reign also illustrates how the autocracy could

continue to operate successfully under an undis-

tinguished female ruler. Her gender proved to be an

advantage, for the last thing the men close to the

throne wanted was another Peter. The new six-man

Supreme Privy Council under Menshikov disman-

tled some of Peter’s unsuccessful experiments in

provincial government, downsized the army and

navy, and reduced the poll tax. In 1726 an alliance

with Austria formed the cornerstone of Russian

diplomacy for decades to come. Peter’s plans for an

Academy of Sciences were implemented, and west-

ern culture remained central for the elite.

Catherine bore Peter probably ten children in

all, but only two survived into adulthood, Anna

(1708–1729) and Elizabeth (1709–1762). Cather-

ine would have preferred to nominate one of them

as her successor, but Menshikov persuaded her to

name Peter’s grandson, who succeeded her as Pe-

ter II in May 1727.

See also: MENSHIKOV, ALEXANDER DANILOVICH; PETER I;

PETER II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, John. (2000). “Catherine I, Her Court and

Courtiers.” In Peter the Great and the West: New Per-

spectives, ed. Lindsey Hughes. Basingstoke, UK: Pal-

grave.

Hughes, Lindsey. (1998). Russia in the Age of Peter the

Great. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

L

INDSEY

H

UGHES

CATHERINE II

(1729–1796) Yekaterina Alexeyevna or “Catherine

the Great,” Empress of Russia from 1762–1796.

Recognized worldwide as a historical figure,

Catherine the Great earned legendary status for

three centuries. Her political ambition prompted the

overthrow and subsequent murder of her husband,

Emperor Peter III (1728–1762). Whatever her

actual complicity, his death branded her an acces-

sory after the fact. Thus she labored to build legit-

imacy as autocratrix (independent ruler) of the

expansive Russian Empire. When her reign proved

long, extravagant praise of her character and im-

pact overshadowed accusation. An outsider adept

at charming Russian society, she projects a power-

ful presence in history. Most associate her with all

significant events and trends in Russia’s expanding

world role. Though she always rejected the appel-

lation “the Great,” it endured.

Catherine fostered positive concepts of her life

by composing multiple autobiographical portray-

als over five decades. None of the different drafts

treated her reign directly, but all implicitly justified

her fitness to rule. Various versions have been

translated and often reissued to reach audiences

worldwide. Ironically, the first published version

was issued in 1859 by Russian radicals in London

to embarrass the Romanov dynasty. Trilingual in

German, French, and Russian, Catherine spelled

badly but read, wrote, spoke, and dictated easily

and voluminously. Keen intelligence, prodigious

memory, broad knowledge, and wit enlivened her

conversational skill.

Born on April 21, 1729, in Stettin, Prussia, of

Germanic parentage, the first daughter of Prince

Christian August of Anhalt-Zerbst (1690–1747)

and Princess Johanna Elizabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

(1712–1760), Sophia Augusta Fredericka combined

precocious physical, social, and intellectual traits

with great energy and inquisitiveness. A home ed-

ucation through governesses and tutors enabled her

by age ten to read voraciously and to converse in-

cessantly with relatives and acquaintances at home

and at other German courts that her assertive

mother visited. At the court of Holstein-Gottorp in

1739 she met a second cousin, Prince Karl Peter Ul-

rich, the orphaned grandson of Peter the Great who

was brought to Russia in 1742 by his childless

aunt, Empress Elizabeth; renamed Peter Fedorovich;

and proclaimed heir apparent. Backed by Frederick

the Great of Prussia, Sophia followed Peter to Rus-

sia in 1744, where she was converted to Ortho-

doxy and renamed Catherine. Their marriage in

1745 granted her access to the Russian throne. She

was to supply a male heir—a daunting task in view

of Peter’s unstable personality, weak health, prob-

able sterility, and impotence. When five years

brought no pregnancy, Catherine was advised to

beget an heir with a married Russian courtier,

Sergei Saltykov (1726–1785). After two miscar-

riages she gave birth to Paul Petrovich on October

1, 1754. Presumably fathered by Saltykov, the

baby was raised by Empress Elizabeth. Thenceforth

Catherine enjoyed greater freedom to engage in

court politics and romantic intrigue. In 1757 she

bore a daughter by Polish aristocrat Stanislaus

CATHERINE II

205

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Poniatowski that only lived sixteen months. Dur-

ing her husband’s short-lived reign in 1762 she

gave birth to another son, Alexei Bobrinskoy, by

Russian aristocrat Grigory Orlov.

Catherine quickly absorbed Russian culture.

She mastered the language, customs, and history

of the empire. An instinctive politician, she culti-

vated friendships among the court elite and select

foreigners such as Sir Charles Hanbury Williams

(who lent her money and political advice). Her cer-

tainty that factional alignments would change

abruptly upon Elizabeth’s death (as foretold by the

exile of Chancellor Alexei Bestuzhev-Ryumin in

1758, the banishment abroad of Stanislaus Ponia-

towski, and her husband’s hostility) fueled her mo-

tivation to form new alliances. When Elizabeth died

suddenly on January 5, 1762, Catherine was preg-

nant by Orlov. Their partisans were unprepared to

contest the throne with the new emperor, Peter III,

who undermined his own authority, alienating the

Guards regiments, the Orthodox Church, and Rus-

sian patriots, through inept policies such as his

withdrawal from war against Prussia and declara-

tion of war on Denmark. Peter rarely saw Cather-

ine or Paul, whose succession rights as wife and

son were jeopardized as Peter delayed his coronation

and flaunted his mistress, Yelizaveta Vorontsova,

older sister of Catherine’s young married friend,

Princess Yekaterina Dashkova.

Peter III was deposed on July 9, 1762, when

Catherine “fled” from suburban Peterhof to St. Pe-

tersburg to be proclaimed empress by the Guards

and the Senate. While under house arrest at Rop-

sha, he was later strangled to death by noblemen

conspiring to ensure Catherine’s sovereign power.

This “revolution” was justified as a defense of Rus-

sian civil and ecclesiastical institutions, prevention

of war, and redemption of national honor. Cather-

ine never admitted complicity in the death of Peter

III which was officially blamed on “hemorrhoidal

colic” a cover-up ridiculed abroad by British writer

Horace Walpole. Walpole scorned “this Fury of the

North,” predicting Paul’s assassination, and refer-

ring to Catherine as “Simiramis, murderess-queen

of ancient times”—charges that incited other scur-

rilous attacks.

Catherine quickly consolidated the new regime

by rewarding partisans, recalling Bestuzhev-

Ryumin and other friends from exile, and ordering

coronation preparations in Moscow, where she was

crowned on October 3, 1762 amid ceremonies that

lasted months. Determined to rule by herself,

Catherine declined to name a chancellor, refused to

marry Grigory Orlov, and ignored Paul’s rights as

he was underage. Her style of governance was cau-

tiously consultative, pragmatic, and “hands-on,”

with a Germanic sense of duty and strong aversion

to wasting time. Aware of the fragility of her al-

legedly absolute authority, she avoided acting like

a despot. She perused the whole spectrum of state

policies, reviewed policies of immigration and re-

organization of church estates, established a new

central administration of public health, and set up

a new commission to rebuild St. Petersburg and

Moscow. Count Nikita Panin, a former diplomat

and Paul’s “governor,” assumed the supervision of

foreign affairs, and in 1764 Prince Alexander Vya-

zemsky became procurator-general of the Senate,

with broad jurisdiction over domestic affairs, par-

ticularly finances and the secret political police.

Catherine’s reign may be variously subdivided,

depending on the sphere of activity considered. One

simplistic scheme breaks it into halves: reform

before 1775, and reaction afterward. But this over-

looks continuities spanning the entire era and ig-

CATHERINE II

206

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

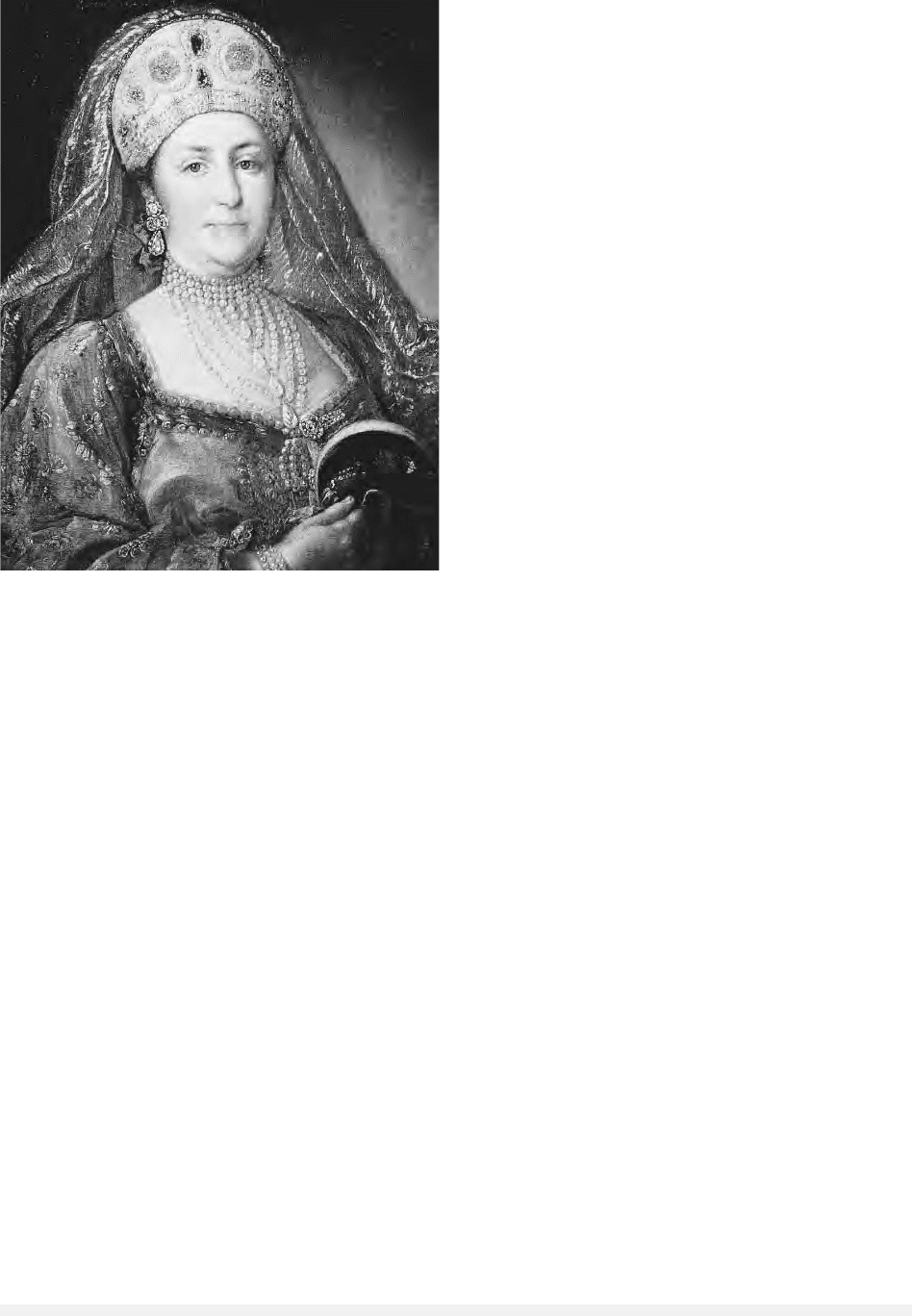

Empress Catherine II in Russian costume. T

HE

A

RT

A

RCHIVE

/R

USSIAN

H

ISTORICAL

M

USEUM

M

OSCOW

/D

AGLI

O

RTI

(A)

nores the varying periodizations for foreign affairs,

education, and culture. Another approach conceives

of her reign as a series of crises. A ruler of wide in-

terests, she dealt simultaneously with diverse mat-

ters. The first decade witnessed her mania for

legislation and pursuit of an active foreign policy

that, in alliance with Prussia from 1764, led to in-

tervention in Poland-Lithuania. This alliance led

to pressures on Poland and spilled over into war

with the Ottoman Empire which in turn yielded

unforeseen complications in the great plague of

1770–1771 and the Pugachev Revolt of 1773–1774.

The latter focused public attention on serfdom,

which Catherine privately despised while recogniz-

ing that it could not be easily changed.

Catherine’s government followed a general pol-

icy of cultivating public confidence in aspirations

to lead Russia toward full and equal membership

in Europe. Drawing on the published advice of Ger-

man cameralist thinkers and corresponding regu-

larly with Voltaire, Diderot, Grimm, and other

philosophers, she promoted administrative efficiency

and uniformity, economic advance and fiscal

growth, and “enlightenment” through expanded

educational facilities, cultural activities, and reli-

gious tolerance. She expanded the Senate in 1762

and 1763, bolstered the office of procurator-gen-

eral in 1763 and 1764, and incorporated Ukraine

into the empire by abolishing the hetmanate in

1764. The Legislative Commission of 1767–1768

assembled several hundred delegates from all free

social groups to assist in recodification of the laws

on the basis of recent European social theory as

borrowed from Montesquieu and others and out-

lined in Catherine’s Great Instruction of 1767—

enlightened guidelines translated into many other

languages. To stimulate the economy, foreign im-

migrants were invited in 1763, grain exports were

sanctioned in 1764, the Free Economic Society was

established in 1765, and a commission on com-

merce formulated a new tariff in 1766. She also

secularized ecclesiastical estates in 1764, founded

the Smolny Institute for the education of young

women, and eased restrictions on religious schis-

matics. New public health policies were championed

as she underwent inoculation against smallpox in

1768 by Dr. Thomas Dimsdale and then provided

the procedure free to the public. Yet her attempts

to contain the horrific plague of 1770–1771 could

not prevent some 100,000 deaths, triggering bloody

riots in Moscow.

The most literate ruler in Russian history,

Catherine constantly patronized cultural pursuits,

especially a flurry of satirical journals and come-

dies published anonymously with her significant

participation. Later comedies attacked Freema-

sonry. In 1768 she founded the Society for the

Translation of Foreign Books into Russian, super-

seded in 1782 by the Russian Academy, which

sponsored a comprehensive dictionary between

1788 and 1796. Most strikingly, she founded the

Hermitage, a museum annex to the Winter Palace,

to house burgeoning collections of European paint-

ings and other kinds of art. To lighten the burdens

of rule, Catherine attended frequent social gather-

ings, including regular “Court Days” (receptions

for a diverse public), visits to the theater, huge fes-

tivals like St. Petersburg’s Grand Carousel of 1766,

and select informal gatherings where titles and

ranks were ignored.

To embrace the great Petrine legacy, Catherine

sponsored a gigantic neoclassical equestrian statue

of Peter the Great on Senate Square, “The Bronze

Horseman” as the poet Pushkin dubbed it, publicly

unveiled in 1782. Dismayed by Peter’s brutal mil-

itarism and coercive cultural innovations, she saw

herself as perfecting his achievements with a lighter

touch. Thus Ivan Betskoy, a prominent dignitary

of the period, lauded them both in 1767 by stat-

ing that Peter the Great created people in Russia but

Catherine endowed them with souls. In neoclassi-

cal imagery Catherine was often depicted as Min-

erva. Her “building mania” involved neo-Gothic

palaces and gardens, and with Scottish architect

Charles Cameron she added a neoclassical wing to

the Catherine Palace at Tsarskoye Selo and the

nearby Pavlovsk Palace for Paul and his second

wife, Maria Fyodorovna, who provided many

grandchildren, the males raised directly by the em-

press.

Through travel Catherine demonstrated vigor

in exploring the empire. In June 1763 she returned

from Moscow to St. Petersburg, then traveled the

next summer to Estland and Livland. She rushed

back because of an attempted coup by a disgrun-

tled Ukrainian officer, Vasily Mirovich, to free the

imprisoned Ivan VI (1740–1764). Acting on secret

orders, guards killed the prisoner before he could

be freed. After a speedy trial Mirovich was beheaded

on September 26, 1764, and his supporters were

beaten and exiled.

While Catherine quickly quashed such inept

plots, she worried more about rumors that Peter

III was alive and eager to regain power. Some dozen

impostors cropped up in remote locales, but all

CATHERINE II

207

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

were apprehended, imprisoned, or exiled. In 1772

and 1773, amid war with the Ottoman Empire, did

fugitive cossack Emelian Pugachev rally the Yaik

cossacks under Peter III’s banner in a regional

rebellion that attracted thousands of motley fol-

lowers. When Pugachev burned Kazan in 1774,

Catherine contemplated defending Moscow in per-

son, but the victorious end of the Russo-Turkish

War soon dissuaded her. Upon capture Pugachev

underwent repeated interrogation before execution

in Moscow on January 21, 1775, in Catherine’s

demonstrative absence. This embarrassment was

overshadowed by elaborate celebrations in Moscow

of victory over Pugachev and the Turks, the Peace

of Kuchuk-Kainardji of 1774.

Russia’s soaring international prestige was fur-

ther affirmed by the month-long visit of King Gus-

tavus III of Sweden in the summer of 1777 and by

Russia’s joint mediation of the war of the Bavar-

ian Succession in the Peace of Teschen of May 1779,

which made Russia a guarantor of the Holy Ro-

man Empire. Catherine’s meeting with Emperor-

King Joseph II of Austria at Mogilev in May 1780

led one year later to a secret Russo-Austrian al-

liance against the Ottoman Empire, the notorious

“Greek Project” that foresaw Catherine’s grandson

Konstantin on the throne of a reconstituted Byzan-

tine Empire. In 1781 Catherine engineered the

Armed Neutrality of 1781, a league of northern

naval powers to oppose British infringement of the

commercial rights of neutrals amid the conflicts

ending the American revolution.

In 1774 Catherine rearranged her personal life

and the imperial leadership by promoting the flam-

boyant Grigory Potemkin, a well-educated noble

and supporter of her coup. Installed as official fa-

vorite, he dominated St. Petersburg politics as po-

litical partner and probable husband until his death

in 1791. He assisted with legislation that spawned

the Provincial Reform beginning in 1775, the Po-

lice Code for towns in 1782, and charters to the

nobility and the towns in 1785. A charter for the

state peasantry remained in draft form, as did re-

forms of the Senate.

In charge of the armed forces, settlement, and

fortification of New Russia (Ukraine), Potemkin

masterminded annexation of the Crimea in 1783

and the Tauride Tour of 1787, an extravagant cav-

alcade that provoked renewed Russo-Turkish war

in August 1787. In alliance with Austria, and de-

spite unforeseen war with Sweden in 1788 and

1790 and troubles in revolutionary France in 1789,

Potemkin coordinated campaigns that confirmed

Russian triumph and territorial gains in the treaty

of Jassy (1792). The last years of Catherine’s life

saw another triumph of Russian arms in the sec-

ond and third partitions of Poland and the prepa-

ration of expeditionary forces against Persia and

France. Internal repercussions of foreign pressures

involved the arrest and exile of Alexander

Radishchev in 1790 and Nikolay Novikov in 1792,

both noblemen charged with publications violating

censorship rules in propagating revolutionary and

Freemason sentiments.

The death of Potemkin and Vyazemsky left

voids in Catherine’s government that a new young

favorite, Platon Zubov, could not bridge. Her de-

clining health and growing estrangement from

Paul insistently raised succession concerns and ru-

mors that she would prevent Paul’s accession.

Catherine’s sudden death on November 16, 1796,

from apoplexy inaugurated his reign. Paul’s efforts

at reversing Catherine’s policies backfired, regener-

ating fond memories that inspired a bogus “Testa-

ment of Catherine the Great” later used by

aristocratic conspirators to overthrow and murder

Paul and replace him with Alexander, Catherine’s

beloved grandson.

CATHERINE II

208

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Empress Catherine II. © H

ULTON

A

RCHIVE

See also: BESTUZHEV-RYUMIN, ALEXIS; INSTRUCTION TO

THE LEGISLATIVE COMMISSION OF CATHERINE II; PE-

TER III; ORLOV, GRIGORY; POTEMKIN, GRIGORY; PU-

GACHEV, EMILIAN; RUSSO-TURKISH WARS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, John T. (1980). Bubonic Plague in Early Mod-

ern Russia: Public Health and Urban Disaster. Balti-

more: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Alexander, John T. (1989). Catherine the Great: Life and

Legend. New York: Oxford University Press.

Alexander, John T. (1999). “Catherine the Great as Porn

Queen.” In Eros and Pornography in Russian Culture,

ed. M. Levitt and A. Toporkov. Moscow: “Ladomir.”

Anthony, Katherine, ed. (1927). Memoirs of Catherine the

Great. New York: Knopf.

Catherine the Great: Treasures of Imperial Russia from the

State Hermitage Museum, Leningrad. (1990). Mem-

phis: City of Memphis, Tennessee, and Leningrad:

State Hermitage Museum.

De Madariaga, Isabel. (1981). Russia in the Age of Cather-

ine the Great. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

De Madariaga, Isabel. (1998). Politics and Culture in Eight-

eenth-Century Russia: Collected Essays. London: Long-

man.

Dixon, Simon. (2001). Catherine the Great. London: Long-

man.

Shvidkovsky, Dimitri. (1996). The Empress and the Ar-

chitect: British Architecture and Gardens at the Court

of Catherine the Great. New Haven, CT: Yale Univer-

sity Press.

J

OHN

T. A

LEXANDER

CATHERINE THE GREAT See CATHERINE II.

CATHOLICISM

The Roman Catholic Church established ties to the

Russian lands from their earliest history but played

only a marginal role. The first significant encounter

came during the Time of Troubles, when the

Catholic associations of pretenders and Polish in-

terventionists triggered intense popular hostility

toward the “Latins” and a hiatus in Russian–

Catholic relations. Only in the last quarter of the

seventeenth century did Muscovy, in pursuit of al-

lies against the Turks, resume ties to Rome. Peter

the Great went significantly further, permitting the

construction of the first Catholic church in Moscow

(1691) and the presence of various Catholic orders

(including Jesuits).

But a significant Catholic presence only com-

menced with the first Polish partition of 1772,

when the Russian Empire acquired substantial

numbers of Catholic subjects. Despite initial ten-

sions (chiefly over claims by the Russian govern-

ment to oversee Catholic administration), relations

improved markedly under emperors Paul (r. 1796–

1801) and Alexander I (r. 1801-1825), when

Catholic—especially Jesuit—influences at court

were extraordinarily strong.

Thereafter, however, relations proved extremely

tempestuous. One factor was the coercive conver-

sion of Uniates or Eastern Catholics (that is,

Catholics practicing Eastern Rites), who were “re-

united” with the Russian Orthodox Church (in

1839 and 1875) and forbidden to practice Catholic

rites. The second factor was Catholic involvement

in the Polish uprisings of 1830-1831 and 1863;

subsequent government measures to Russify and

repress the Poles served only to reinforce their

Catholic identity and resolve. Hence Catholicism re-

mained a force to be reckoned with: By the 1890s,

it had 11.5 million adherents (9.13% of the popu-

lation), making it the third largest religious group

in the Russian Empire. It maintained some 4,400

churches (2,400 in seven Polish dioceses; 2,000 in

five dioceses in the Russian Empire proper). The

1905 revolution forced the regime to declare reli-

gious tolerance (the manifesto of April 17, 1905);

with conversion from Russian Orthodoxy decrim-

inalized, huge numbers declared themselves Catholic

(233,000 in 1905-1909 alone).

The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, however,

brought decades of devastating repression. The

Catholic Church refused to accept Bolshevik na-

tionalization of its property and the requirement

that the laity, not clergy, register and assume re-

sponsibility for churches. The conflict culminated

in the Bolshevik campaign to confiscate church

valuables in 1922 and 1923 and a famous show

trial that ended with the execution of a leading

prelate. That was but a prelude to the 1930s, when

massive purges and repression eliminated all but

two Catholic churches by 1939. Although World

War II brought an increase in Catholic churches

(mainly through the annexation of new territories),

the regime remained highly suspicious of Catholi-

cism, especially in a republic like Lithuania, where

ethnicity and Catholicism coalesced into abiding

dissent.

CATHOLICISM

209

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The “new thinking” of Mikhail Gorbachev in-

cluded the reestablishment of relations with the

Vatican in 1988 and relaxation of pressure on the

Catholic church in the USSR. The breakup of the

Soviet Union in 1991 turned the main bastions of

Catholicism (i.e., Lithuania) into independent re-

publics, but left a substantial number of Catholics

in the Russian Federation (1.3 million according to

Vatican estimates). To minister to them more ef-

fectively, Rome, in February 2002, elevated its four

“apostolic administrations” to the status of “dioce-

ses,” serving some 600,000 parishioners in 212

registered churches and 300 small, informal com-

munities.

See also: LITHUANIA AND LITHUANIANS; ORTHODOXY;

POLAND; RELIGION; UNIATE CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Zatko, James. (1965). Descent into Darkness: The Destruc-

tion of the Roman Catholic Church in Russia, 1917-

1923. Toronto: Baxter Publishing.

Zugger, Christopher. (2001). The Forgotten: Catholics of

the Soviet Empire from Lenin to Stalin. Syracuse, NY:

Syracuse University Press.

G

REGORY

L. F

REEZE

CAUCASIAN WARS

Russian contacts, both diplomatic and military,

with the Caucasus region began during the rule of

Ivan IV in the sixteenth century. However, only

much later, during the reign of Catherine II in the

late eighteenth century, did Russian economic and

military power permit sustained, active involve-

ment. Catherine appointed Prince Grigory Potemkin

Russia’s first viceroy of the Caucasus in 1785, al-

though the actual extent of Russian control reached

only as far south as Mozdok and Vladikavkaz.

Meanwhile, military campaigns guided by Potemkin

and General Alexander Suvorov penetrated far

along the Caspian and Black Sea coasts. Russian in-

trusion energized hostility among much of the pre-

dominantly Muslim populace of the northern

Caucasus, culminating in the proclamation of a

“holy war” by Shaykh Mansur, a fiery resistance

leader. Despite military collaboration with the

Turks and Crimean Tatars, Mansur was captured

by Russian forces at Anapa in 1791. At the time of

the Empress’ death in 1796, the so-called Caucasian

Line, a sequence of forts and outposts tracing the

Kuban and Terek Rivers, marked the practical lim-

its of Russian authority.

Meanwhile, it was Russia’s relationship with

the small Christian kingdom of Georgia that set the

stage for protracted warfare in the Caucasus in the

nineteenth century. Pressed militarily by its pow-

erful Muslim neighbors to the south, Persia and Ot-

toman Turkey, Georgia sought the military

protection of Russia. In 1799, just four years after

a Persian army sacked the capital of Tiflis, Georgy

XII asked the tsar to accept Georgia into the Rus-

sian Empire. The official annexation of Georgia oc-

curred in 1801 under Tsar Alexander I.

The acquisition of Georgia created a geopoliti-

cal anomaly that all but assured further fighting

in the Caucasus. By 1813, following war with Per-

sia, Russia was firmly positioned in the middle of

the region with territorial claims spanning from

the Caspian to the Black Sea. However, most of the

heavily Muslim north central Caucasus was un-

reconciled to Russian domination. In a practical

sense, Georgia constituted an island of Russian

power in the so-called Transcaucasus whose lines

of communications to the old Caucasian Line were

ever precarious. Soon Dagestan, Chechnya, and

Avaria in the east and the Kuban River basin in the

west emerged as major bastions of popular resis-

tance. Particularly in the interior of the country,

among the thick forests and rugged mountains of

the northern slopes of the Caucasus Mountains, the

terrain as well as throngs of able guerrilla warriors

posed a formidable military obstacle. As in any

such unconventional conflict, Russia had to stretch

its resources both to protect friendly populations

and prosecute a complex political-military struggle

against a determined opposition. To secure areas

under imperial authority, the Russians established

a loose cordon of fortified points around the moun-

tains. This, however, proved insufficient to prevent

hostile raids. Meanwhile, the Russian effort to

subjugate the resistance, widely known as the

“mountaineers” or gortsy, required the ever in-

creasing application of armed force. In the view of

General Aleksei Petrovich Ermolov, commander of

the Caucasus, the mountains constituted a great

fortress, difficult to either storm or besiege.

Roughly speaking, the Russian subjugation of

the mountaineer resistance is divisible into three

stages. From 1801 to 1832, Russia’s campaigns

were sporadic, owing in part to the distraction of

intermittent warfare with Persia, Turkey, Sweden,

and France. In addition, the threat to Russian rule

CAUCASIAN WARS

210

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

in the Caucasus did not for several decades appear

extremely serious. This situation changed in the

early 1830s as the resistance assumed increasingly

religious overtones. In 1834, a capable and charis-

matic resistance leader emerged in the person of

Shamil, an Avar who headed a spiritual movement

described by the Russians as “muridism” (derived

from the term murid, meaning disciple). Combin-

ing religious appeal with military and administra-

tive savvy, Shamil forged an alliance of mountain

tribes that fundamentally transformed the charac-

ter of the war.

Although the true center of Shamil’s strength

lay in the mountains of eastern Dagestan, his

power was equally dependent upon the support of

the Chechen tribes inhabiting the forested slopes

and foothills between Georgia and the Terek River.

Also important to the eastern resistance were the

Lezghian tribes along the fringes of the Caucasian

range. Because it was not strongly linked to Shamil,

the Russians were less concerned in the short term

with resistance in the western Caucasus (the

southern Kuban and Black Sea coast), and formally

treated that area as a separate military theater from

1821.

From the early 1830s, the Russians relied in-

creasingly on large, conventional campaigns in an

effort to shatter Shamil’s resistance in a single cam-

paign. This strategy did not produce the desired re-

sults. Although the tsar’s columns proved repeatedly

that they could march deep into the rugged inte-

rior of the region to assault and capture virtually

any rebel position, Shamil’s forces would not stand

still long enough to risk total defeat. Moreover,

upon retreating from the mountains, where it was

impossible to supply Russian armies for more than

a few weeks, Russian forces suffered repeated am-

bushes and loss of prestige The last such attempt

was the nearly disastrous expedition of 1845. Un-

der the command of the new Viceroy of the Cau-

casus, Prince Mikhail Vorontsov, a force of about

eighteen thousand, including one thousand native

militiamen, drove deep into the mountains and

stormed a fiercely defended fort at Dargo. Yet, the

mountaineers managed to evade total destruction

by melting away into the surrounding forests.

CAUCASIAN WARS

211

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

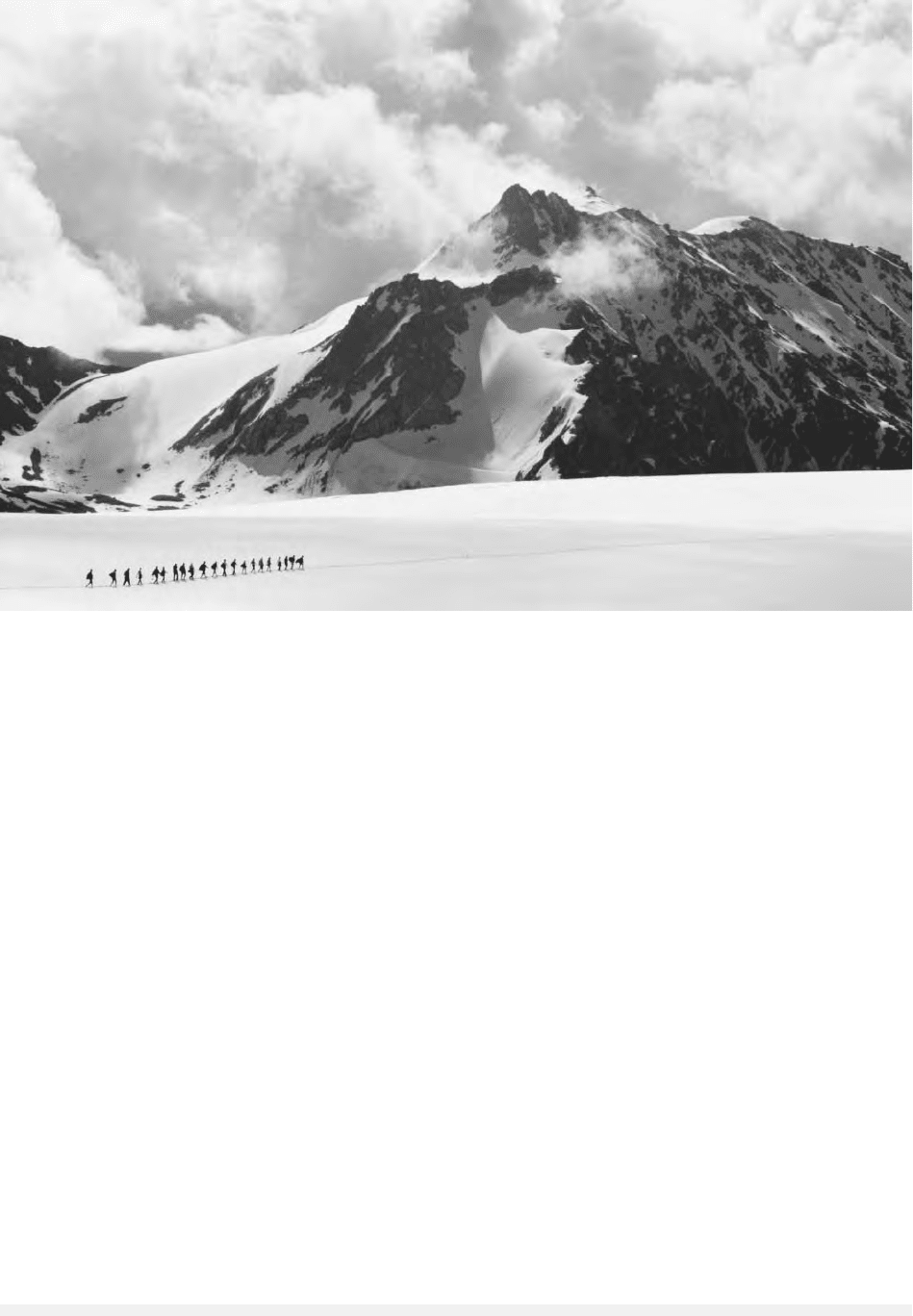

View of Caucasus Mountains from Mount Elbrus. © D

EAN

C

ONGER

/CORBIS

Upon their return from the mountains, Russian

troops suffered incessant harassment by unseen

snipers and were cut off from resupply. Only the

arrival of a relief column prevented a complete de-

bacle, but the invaders endured more than three

thousand casualties during the campaign.

Finally, in 1846, Russian strategy changed to

reflect a more patient and methodical modus

operandi. Russia refocused its efforts on limited,

achievable objectives with the overall intent of

gradually reducing the territory under Shamil’s in-

fluence. The advent of the Crimean War disrupted

Russian progress as the diversion of Russian regi-

ments to fighting the Turks served once again to

encourage popular resistance. However, with the

conclusion of that war in 1856, the empire resolved

to finish its increasingly tiresome struggle for do-

minion over the Caucasus by massing its strength

in the region for the first time.

To accomplish this, the new viceroy, General

Alexander I. Baryatinsky, retained control of forces

assumed committed against Turkey in the Cau-

casian theater. With approximately 250,000 sol-

diers at his disposal, Baryatinsky was able to apply

relentless pressure against multiple objectives by

mounting separate but converging campaigns. He

was ably served in this endeavor by Dmitry Mi-

lyutin, the future War Minister, as chief of staff.

Both men were veterans of fighting in the Cauca-

sus and understood the necessity to separate the

resistance from the general population. They ruth-

lessly achieved this end by systematically clearing

and burning forests, destroying villages, and forcibly

resettling entire tribes, thereby progressively deny-

ing Shamil access to critical resources. Following

the fall of Shamil’s key stronghold at Veden in

1859, the Russians captured the resistance leader

himself at Gunib. Then, having gained success in

the east, Russian forces liquidated remaining op-

position in the west during the next several years.

Ultimately, as many as half a million Moslem

tribesmen, above all Cherkes in the west, were re-

located from their ancestral lands.

See also: BARYATINSKY, ALEXANDER IVANOVICH; CAU-

CASUS; GEORGIA AND GEORGIANS; MILYUTIN, DMITRY

ALEXEYEVICH; SHAMIL; VORONTSOV, MIKHAIL SE-

MENOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baddeley, John. (1908). The Russian Conquest of the Cau-

casus. New York: Longmans, Green and Co.

Baumann, Robert. (1993). Russian-Soviet Unconventional

Wars in the Caucasus, Central Asia and Afghanistan.

Ft. Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute.

Gammer, Moshe. (1994). Muslim Resistance to the Tsar:

Shamil and the Conquest of Chechnia and Daghestan.

London and Portland, OR: F. Cass.

R

OBERT

F. B

AUMANN

CAUCASUS

The Caucasus region is a relatively compact area

centered on the Caucasus Mountains. The foothills

to the north and some of the steppe connected to

them form a northern border, while the southern

border can be defined by the extent of the Armen-

ian plateau. The Black Sea in the west and the

Caspian Sea in the east form natural boundaries in

those directions. It is a territory of immense eth-

nic, linguistic, and national diversity, and it is cur-

rently spread over the territory of four sovereign

nations.

The Caucasus region has long been known for

the diversity of its peoples. Pliny the Younger in

the first century, writing in his Natural History

(Book VI.4.16), cited an earlier observer, Timos-

thenes, to the effect that three hundred different

tribes with their own languages lived in the Cau-

casus area, and that Romans in the city of Dioscu-

rias, encompassing land now in the Abkhaz city of

Sukhumi, had employed a staff of 130 translators

in order for business to be carried out.

The relative remoteness of the Caucasus from

the Greek and Romans lands led to erroneous ideas

concerning its location, not to mention exotic

claims for its people. Some thought that the moun-

tains extended far enough to the east that they

joined with the Himalayas in India. The Caucasus

was the scene of the legendary Prometheus’ cap-

tivity, the goal of Jason’s Argonauts in their quest

for the Golden Fleece, and the homeland of the fa-

mous and fantastic fighting women known as

Amazons. When Pompey invaded the region, he

was said to have wanted to see the mountain where

Prometheus had been chained.

The main Caucasus range is often considered

part of the boundary that separates the state of

mind that is Europe from that of Asia, despite as-

pirations of people to the south to be a part of Eu-

rope. The highest peak is Mount Elbrus at 18,510

feet (5,642 meters), making it the highest in Eu-

CAUCASUS

212

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY