Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Prior to the Russian conquest, Chechen society

was prosperous and egalitarian, with no social dis-

tinctions other than earned wealth and earned

honor. There was no government, though the so-

ciety was ruled by a strong and uniform code of

law. Penalties were set by respected elders, and fines

were collected or death penalties carried out by the

victim or the offended family. (The misnomers

“blood feud,” “vendetta,” and “vengeance” are com-

monly used of this decentralized system.) Tradi-

tional justice has served the Chechens through the

Soviet and post-Soviet periods whenever civil jus-

tice has failed to function.

Chechen social interaction is based on princi-

ples of honor, chivalry, hospitality, and respect,

and on formality between certain individuals and

families. Relations within the family are close and

warm, but in public or when guests are present

younger brothers are formal in the presence of older

brothers and all are formal in the presence of their

father. Behavior of men toward women, whether

formal or not, is always chivalrous. Unlike some

Muslim societies, Chechen women are and always

have been free to associate with men in public, hold

positions of responsibility in all lines of work, su-

pervise men at work, and so on, but chivalry is

strictly observed and creates social distance between

men and women. An individual’s social standing

depends largely on how well he or she shows re-

spect and extends hospitality to others.

From the middle ages to the sixteenth or sev-

enteenth century, Chechen families of means built

five-story defense towers and two-story dwelling

compounds of stone in highland villages, usually

one tower per village. Today, each tower is associ-

ated with a clan that traces its origin to that vil-

lage, and each highland village is (or was until

deportations in the Soviet era) inhabited by one clan

that owns communal fields and pastures, a ceme-

tery, and (prior to the conversion to Islam) one or

more shrines. The majority of Chechen clans have

such highland roots; a few lowland clans do not,

and these are generally assimilated clans originally

of other nationalities.

The Chechen highlands, though the center of

clan and pre-Muslim religious identity, supported

a limited population and therefore traditional

Chechen society was vertically distributed, with

highlanders (herders) and lowlanders (grain farm-

ers) economically dependent on each other. In cold

periods such as the Little Ice Age (middle ages to

mid-nineteenth century), highland farming became

marginal and downhill movement increased. The

late middle ages were a time of intensification in

the forested foothills of Chechnya, when foothill

towns were founded, ethnic identity as noxchi be-

gan to spread through the foothills, and the low-

lands became the wealthier and culturally

prestigious part of the society. The peak of the Lit-

tle Ice Age coincided with the beginning of the Rus-

sian conquest of the Caucasus in the eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries, and the Chechen economy

was destroyed as the lowlanders were expelled,

their lands seized, and at least half of the lowland

population slaughtered or deported to the Ottoman

Empire (the Chechens of Jordan, Turkey, and Syria

are descendants of these and postwar deportees).

HISTORY, TREATIES,

EXTERNAL RELATIONS

In 1859 Imam Shamil, leader of the fierce Dagestani-

Chechen resistance to Russian conquest, surren-

dered to the Russian forces. No nation or government

surrendered, and in particular the Chechens did not

surrender (and indeed had no government that

CHECHNYA AND CHECHENS

233

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

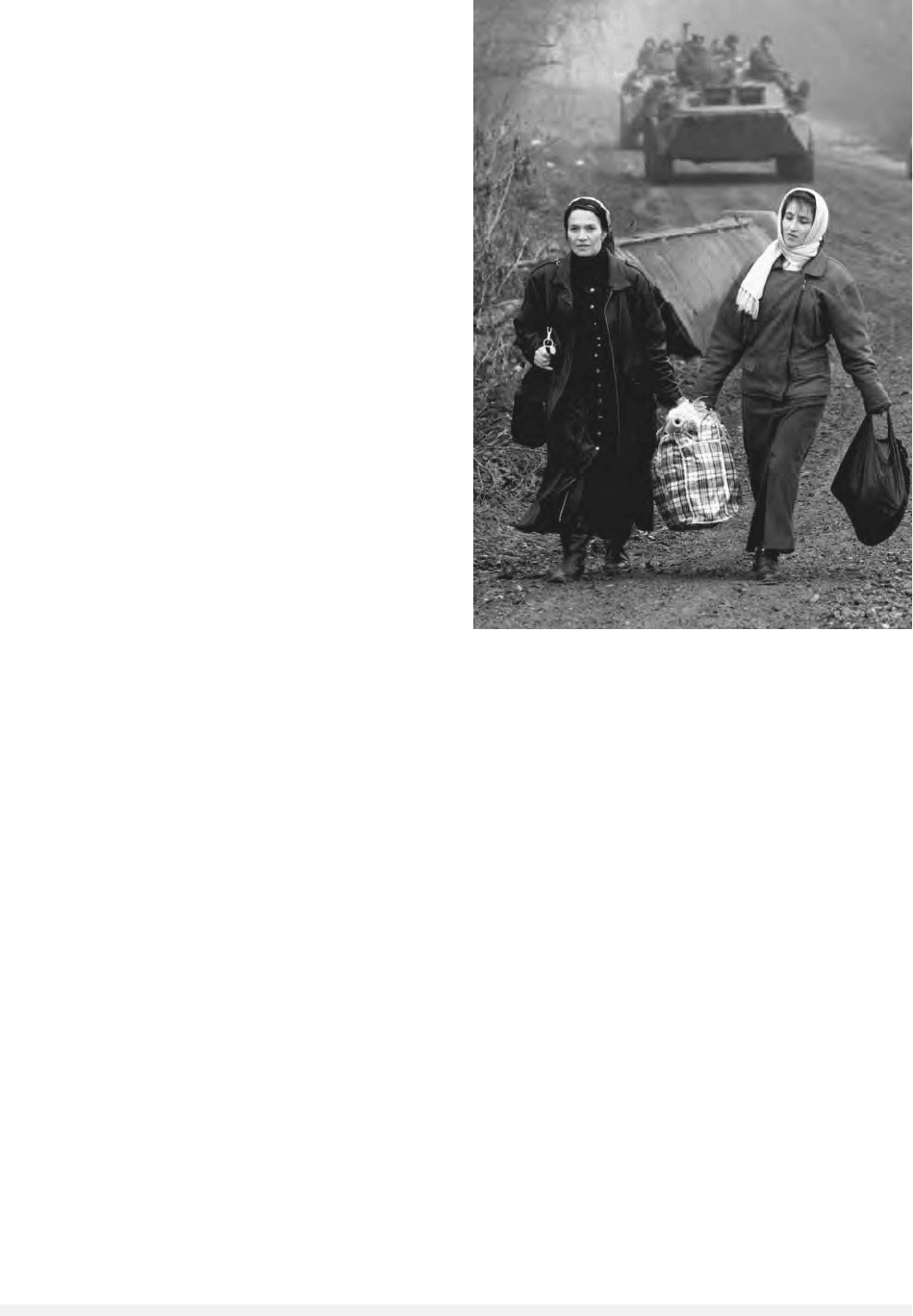

Chechen women flee the village of Assinovskaya for neighboring

Ingushetia, December 1999. © R

EUTERS

N

EW

M

EDIA

I

NC

./CORBIS

could have surrendered) and have essentially never

considered themselves legitimately part of Russia.

Their best land was seized and given to Cossack or

Russian settlers, and perhaps half of their surviv-

ing population was deported or coerced or deceived

into emigrating to the Ottoman Empire. A large

Chechen uprising in 1877–78 was put down by

Russian military force. A North Caucasus state, the

Mountain Republic, including Chechnya, formed in

1917 and declared its independence in 1918. Indi-

vidual North Caucasian groups, including the

Chechens, fought against the Whites in the Rus-

sian civil war. In 1920 the Red Army occupied the

North Caucasus lowlands but then oppressed the

population and a yearlong war in Chechnya and

Daghestan ensued. A Soviet Mountain Republic (the

North Caucasus minus Daghestan) in 1921 recog-

nized the Soviet government on the latter’s promise

(via nationalities commissar Josef Stalin) of reli-

gious and internal-political autonomy. But in 1922

the Bolsheviks attacked Chechnya (to “pacify” it),

removed it from the Mountain Republic, and in

1924 “liquidated” the rest of the Republic. In 1925

there was another bloody “pacification” of Chech-

nya. In a 1929 Chechen rebellion against collectivi-

zation, the leaders created a provisional government

and presented formal demands to the Soviet gov-

ernment, which officially promised Chechen au-

tonomy but attacked again soon after. Probably at

least thirty thousand Chechens were killed in

purges connected with collectivization. In 1936

Chechnya was merged with Ingushetia into a hy-

brid Chechen-Ingush ASSR. In 1944 the entire

Chechen and Ingush population was deported and

the ASSR “liquidated.” They were “rehabilitated” in

1956 and the ASSR reinstituted in 1957. In 1991

Chechnya declared independence and Ingushetia

separated off. The 1994–1996 Russian-Chechen War

was initiated in part to prevent Chechnya’s seces-

sion. The 1997 Khasavyurt treaty after the war

promised Russian withdrawal from and noninter-

ference in Chechnya, a decision on independence af-

ter five years, and Russian aid in rebuilding the

devastated country. (The wording implies Chechen

independence; e.g. “The agreement on the funda-

mentals of relations between Russian Federation

CHECHNYA AND CHECHENS

234

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

A Russian soldier aims his machine gun during Russia’s second war with Chechnya. © AFP/CORBIS

and the Chechen Republic being determined in ac-

cordance with generally recognized norms of in-

ternational law shall be reached prior to December

31, 2001.”) This is the first treaty the Chechens

have made as a nation. They honored it; Russia did

not, but diverted aid funds, supported radical Is-

lamists and militants, began planning to invade

Chechnya in early 1999, and did so on a pretext in

late 1999, initiating a destructive war designed to

solidify political power in Moscow but otherwise

still incompletely understood.

The Chechen demographic losses of the twenti-

eth century are: 1920–1921 Red Army invasion,

nearly 2 percent of the population killed; collec-

tivization in 1931, more than 8 percent; 1937

purges, more than 8 percent; mass deportation in

1944, 22 percent killed in the deportation process

and another 24 percent dead of starvation and

cold in the first two or three years afterward;

1994–1996 Russian-Chechen War, between 2 per-

cent and 10 percent (figures vary), mostly civilians;

a similar figure for the second Russian-Chechen

War, begun in 1999; conservative total well over

60 percent. In the early twenty-first century many

Chechens are war refugees or otherwise displaced.

The overarching cause has probably been Russian

official hate dating back to the nineteenth century

when the Chechens were the largest and most vis-

ible of the groups resisting Russian conquest, fueled

by continued Chechen nonassimilation and resis-

tance. Besides many civilian deaths and refugees the

two wars have brought numerous violations of

Chechen human rights by Russian forces, destruc-

tion of the economy and infrastructure of Chech-

nya, open prejudice and violence against southern

peoples across Russia, and a small but conspicuous

radical Islamist movement in Chechnya.

See also: CAUCASIAN WAR; CAUCASUS; DEPORTATIONS;

NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Avtorkhanov, Abdurakhman. (1992). “The Chechens and

Ingush during the Soviet Period and its Antecedents.”

In The North Caucasus Barrier, ed. Marie Bennigsen

Broxup. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Dunlop, John B. (1998). Russia Confronts Chechnya: Roots

of a Separatist Conflict. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Dunlop, John B. (2000—2002). Chechnya Weekly. Vols.

1–3. Washington, DC: Jamestown Foundation.

<http://chechnya.jamestown.org/pub_chechnya

.htm>.

Lieven, Anatol. (1998). Chechnya: Tombstone of Russian

Power. New Haven, CT, and London: Yale Univer-

sity Press.

Nekrich, Aleksandr M. (1978). The Punished Peoples: The

Deportation and Fate of Soviet Minorities at the end of

the Second World War. New York: Norton.

Politkovskaya, Anna. (2001). A Dirty War: A Russian Re-

porter in Chechnya. London: Harvill.

Uzzell, Lawrence A. (2003). Chechnya Weekly. Vols. 4ff.

Washington, DC: Jamestown Foundation. <http://

chechnya.jamestown.org/pub_chechnya.htm>.

Williams, Brian Glyn. (2000). “Commemorating ‘The

Deportation.’” Post-Soviet Chechnya History and Mem-

ory 12: 101–134.

Williams, Brian Glyn. (2001). “The Russo-Chechen War:

A threat to Stability in the Middle East and Russia?”

Middle East Policy 8:128–148.

J

OHANNA

N

ICHOLS

CHEKHOV, ANTON PAVLOVICH

(1860–1904), short-story writer and dramatist.

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov was the author of

several hundred works of short fiction and of sev-

eral plays that are among the most important and

influential dramatic works of the twentieth cen-

tury. He was also a noted public figure who in his

opinions and actions often challenged notions that

were dominant in Russian social thought of the

time.

Chekhov was born the grandson of a serf, who

had purchased his freedom prior to the emancipa-

tion of the serfs, and the son of a shop owner in

the Black Sea port of Taganrog, a town with a very

diverse population. He received his primary and sec-

ondary education there, first in the parish school

of the local Greek church, and from 1868 in the

Taganrog Gymnasium, where his religion instruc-

tor, a Russian Orthodox priest, introduced his

students to works of Russian and European litera-

ture. In 1876 his father declared bankruptcy, and

the family moved to Moscow to avoid creditors.

Chekhov remained in Taganrog to finish at the

Gymnasium. During this period, he apparently

read literature intensively in the Taganrog public

library and began to write works of both fiction

and drama. In 1879 Chekhov completed the Gym-

nasium, joined his family in Moscow, and began

study in the medical department of Moscow Uni-

versity.

CHEKHOV, ANTON PAVLOVICH

235

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Chekhov later credited his medical education

with instilling in him a respect for objective obser-

vation and attention to individual circumstances.

While in medical school, at the suggestion of his

elder brother Alexander, a journalist, Chekhov be-

gan to contribute to the so-called satirical journals,

weekly periodicals that appealed primarily to

lower-class urban readers with a mix of drawings,

humorous sketches, and other brief entertainment

items. By the time Chekhov finished his medical

courses in 1884, he was already established as a

successful writer for the satirical journals and was

the primary support for his parents and siblings.

Although Chekhov never entirely abandoned med-

icine, by the mid-1880s he devoted his efforts

mainly to his career as a writer, gradually gaining

access to increasingly serious (and better-paying)

newspapers and journals, most notably in New

Times, published by the influential newspaper mag-

nate Alexei Suvorin, and then in various “thick

journals.” Chekhov first appeared in a thick jour-

nal in 1888 with his long story “The Steppe,” pub-

lished in the Populist journal Northern Herald. From

that point on, Chekhov received increasing renown

as the most significant, if problematic, author of

his generation. Through his objectivity and tech-

niques of economy and implication, as well as the

increasing seriousness and complexity of his

themes, Chekhov emerged as a founder of the mod-

ern short story and one of the most influential

practitioners of the form. Such works as “Sleepy,”

“The Steppe,” “The Name-Day Party” (all 1888),

“A Boring Story” (1889), “The Duel” (1891), “The

Student” (1894), “My Life” (1896), and “The Lady

with a Lapdog” (1899) rank among the greatest

achievements of short fiction.

In drama, after hits with several one-act farces

but mediocre success with serious full-length plays,

Chekhov emerged as an innovator in drama with

the first of his four major plays, The Seagull (1895).

Although the first production in Petersburg in 1896

continued Chekhov’s string of theatrical failures, a

new production by the newly formed Moscow Art

Theater in 1898, based on new principles of stag-

ing and acting, won belated recognition as a new

departure in drama. Subsequent Moscow Art The-

ater productions of Uncle Vanya (staged 1899),

Three Sisters (1901), and The Cherry Orchard (1904)

solidified Chekhov’s reputation as a master of a

new type of drama and led to the worldwide in-

fluence of his plays and of Moscow Art Theater

techniques. In addition, Chekhov’s association with

the Moscow Art Theater led to his marriage to one

of the theater’s actresses, Olga Leonardovna Knip-

per, in 1901.

In addition to his strictly literary activity, Chek-

hov also was engaged in a number of the social is-

sues of his day. For instance, he assisted schools and

libraries in his hometown of Taganrog, Melikhovo

(the village near his estate), and Yalta, and served

as a district medical officer during a cholera out-

break while he was living at Melikhovo. He also ini-

tiated practical programs for famine relief during a

crop failure in 1891 and 1892. Earlier, in 1890, he

undertook the arduous journey across Siberia to the

island of Sakhalin, which served at the time as a

Russian penal colony. There Chekhov conducted a

detailed sociological survey of the population and

eventually published his observation as a book-

length study of the island and its inhabitants, The

Island of Sakhalin (1895), a work that eventually

brought about amelioration of penal conditions.

Most famously, Chekhov broke with his longtime

friend, patron, and editor Suvorin over Suvorin’s

support of Alfred Dreyfus’s conviction for espionage

in France and opposed the anti-Semitic stance taken

by Suvorin’s paper New Times.

CHEKHOV, ANTON PAVLOVICH

236

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

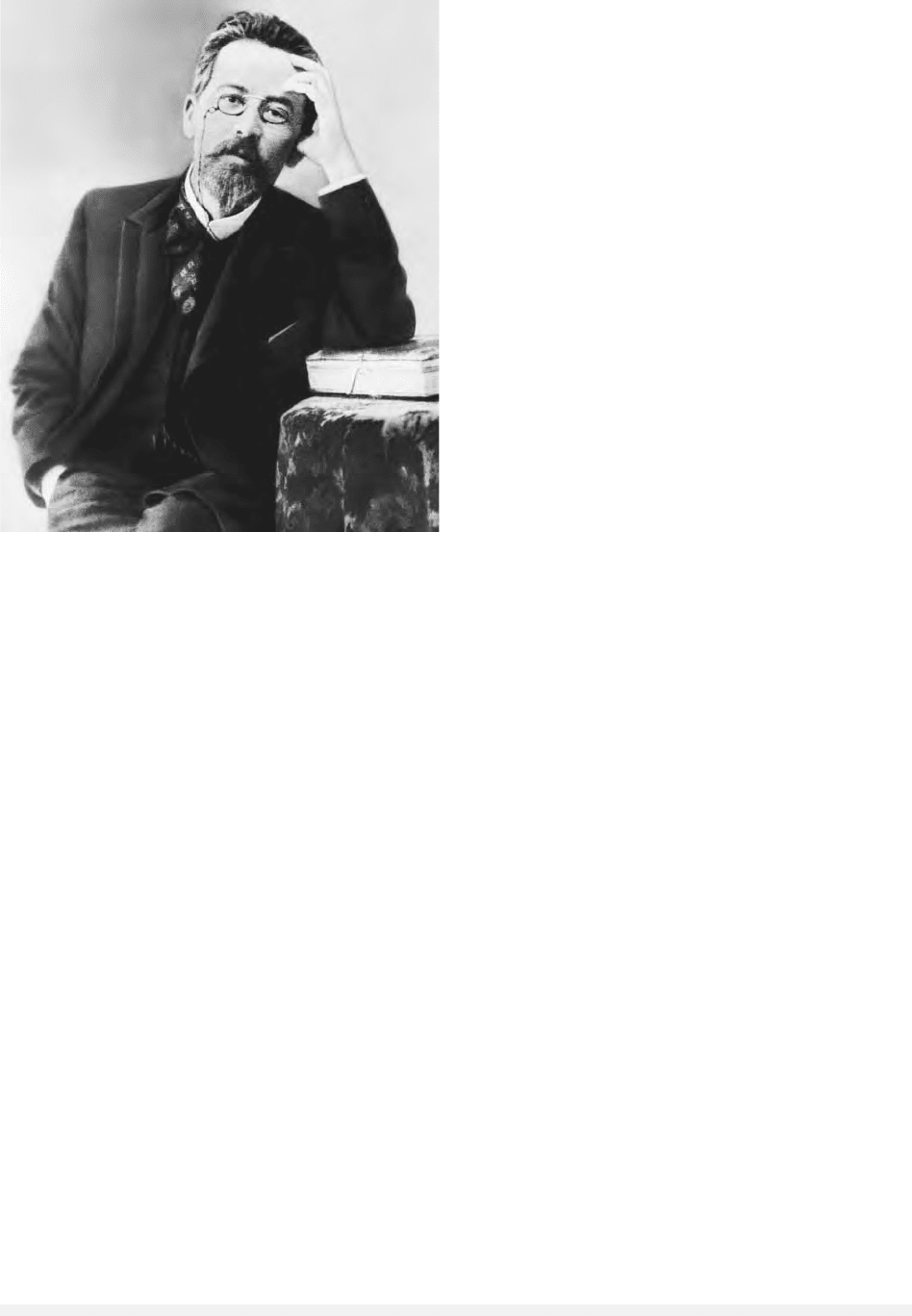

Novelist and playwright Anton Chekhov. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

From the 1880s until his death, Chekhov suf-

fered from tuberculosis, a disease that necessitated

his move in 1898 from a small estate (purchased

in 1892) outside Moscow to the milder climate of

Yalta in the Crimea. He also spent time on the

French Riviera. Finally in 1904 he went to Germany

in search of treatment and died in Badenweiler in

southern Germany in July of that year.

See also: MOSCOW ART THEATER; SUVORIN, ALEXEI

SERGEYEVICH; THICK JOURNALS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Heim, Michael Henry, and Karlinsky, Simon, tr. (1973).

Anton Chekhov’s Life and Thought: Selected Letters and

Commentary. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rayfield, Donald. (1998). Anton Chekhov: A Life. New

York: Henry Holt.

Simmons, Ernest J. (1962). Chekhov: A Biography. Boston:

Little, Brown.

A

NDREW

R. D

URKIN

CHERKESS

The Cherkess are one of the two titular nationali-

ties of the north Caucasian Republic of Karachaevo-

Cherkessia in the Russian Federation. In the Soviet

period this area underwent several administrative

reorganizations but was then established as an au-

tonomous oblast (province) within the Stavropol

Krai. The capital is Cherkessk and was founded in

1804. The Cherkess form only about 10 percent of

the oblast’s population, which numbers 436,000

and 62 percent of whom make their livings in agri-

culture, animal husbandry, and bee-keeping. Health

resorts are also an important local source of em-

ployment and revenue here, as it is in most of the

North-West Caucasian region.

The Cherkess belong to the same ethnolinguis-

tic family as the Adyge and the Kabardians, who

live in neighboring republics, and they speak a sub-

dialect of Kabardian, or “Eastern Circassian.” Soviet

nationalities policies established these three groups

as separate “peoples” and languages, but historical

memory and linguistic affinity, as well as post-So-

viet ethnic politics, perpetuate notions of ethnic

continuity. An important element in this has been

the contacts, since the break-up of the Soviet

Union, with Circassians living in Turkey, Syria, Is-

rael, Jordan, Western Europe, and the United

States. These are mostly the descendents of mi-

grants who left for the Ottoman Empire in the mid-

and late nineteenth century after the completion of

the Russian conquest of the Caucasus. The long and

painful process of conquest firmly established “the

idea of Circassians” as “noble savages” in the Russ-

ian imagination.

The Cherkess are Muslims, but other religious

influences can be discerned in their cultural prac-

tices, including Greek Orthodox Christianity and

indigenous beliefs and rituals. The Soviet state dis-

couraged the practice of Islam and the perpetua-

tion of Muslim identity among the Cherkess, but

it supported cultural nation-building. In the post-

Soviet period, interethnic tensions were clearly

apparent in the republic’s presidential elections.

However, Islamic movements, generally termed

“Wahhabism,” are in less evidence among the

Cherkess than with other groups in the North Cau-

casus. The wars in Abkhasia (from 1992 to 1993)

and Chechnya (1994–1997; 1999–2000) have also

affected Cherkess sympathies and politics, causing

the Russian state to intermittently infuse the North

West Caucasus republics with resources to prevent

the spreading of conflict.

See also: ADYGE; CAUCASUS; KABARDIANS; NATIONALI-

TIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES,

TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baddeley, John F. (1908). The Russian Conquest of the Cau-

casus. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

Borxup, Marie Bennigsen. Ed. (1992). The North Cauca-

sus Barrier: The Russian Advance towards the Muslim

World. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Gammer, Moshe. (1994). Muslim Resistance to the Tsar:

Shamil and the Conquest of Chechnia and Daghestan.

London: Frank Cass.

Jaimoukha, Amjad. (2001). The Circassians: A Handbook.

New York: Palgrave.

Jersild, Austin. (2002). Orientalism and Empire: North

Caucasus Mountain Peoples and the Georgian Frontier,

1854–1917. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queens

University Press.

Matveeva, Anna. (1999). The North Caucasus: Russia’s

Fragile Borderland. Great Britain: The Royal Institute

of International Affairs.

S

ETENEY

S

HAMI

CHERKESS

237

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

CHERNENKO, KONSTANTIN USTINOVICH

(1911-1985), general secretary of the Communist

Party of the Soviet Union (1983-1985).

Konstantin Chernenko was born on September

24, 1911, in a village in the Krasnoyarsk region of

Russia. He spent his entire career in the party and

worked his way up the ranks in the field of agita-

tion and propaganda. In 1948 he became the head

of the Agitation and Propaganda Department in the

new Republic of Moldavia. There he got to know

the future party leader Leonid Brezhnev, who be-

came the republic’s first secretary in 1950. Cher-

nenko rode Brezhnev’s coattails to the pinnacle of

Soviet power. After Brezhnev became a Central

Committee secretary, he brought Chernenko to

Moscow in 1956 to work in the party apparatus.

When Brezhnev became the chairman of the USSR

Supreme Soviet in 1960, he appointed Chernenko

the head of its secretariat. After Brezhnev became

General Secretary, Chernenko became the head of

the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU)

General Department in 1965, a Central Committee

secretary in 1976, a candidate member of the Polit-

buro in 1977, and a full member of the Politburo

in 1978. In the Secretariat Chernenko oversaw its

administration and controlled the paper flow

within the party.

At the end of his life, Brezhnev was actively ad-

vancing Chernenko to be his successor. In the late

1970s and early 1980s, Chernenko was given a

broader role in the party and a higher profile than

any of the other contenders: He traveled frequently

with Brezhnev and published numerous books and

articles. In an apparent effort to show that he

would pay attention to the growing pressures for

reform of the Soviet system, Chernenko started an

active campaign for paying more attention to cit-

izens’ letters to the leadership. He also stressed the

importance of public opinion and the need for

greater party democracy. He warned that dangers

similar to those that arose from Poland’s Solidar-

ity movement could happen in the Soviet Union if

public opinion was ignored. However, his experi-

ence in the party remained very limited, and he

never held a position of independent authority.

When Brezhnev died in November 1982, Cher-

nenko was passed over, and the party turned to the

more experienced Yuri Andropov as its new leader.

However, when Andropov died a little over a year

later in February 1984, the party chose the sev-

enty–two–year–old Chernenko as its leader. This

was a last desperate effort by the sclerotic Brezh-

nev generation to hold on to power and block the

election of Mikhail Gorbachev, who was Cher-

nenko’s chief rival for the job and had been ad-

vanced by Andropov. As had become the practice

after Brezhnev became party leader, Chernenko also

served as Chairman of the Presidium of the

Supreme Soviet, the head of state.

Chernenko served only thirteen months as

party leader. During the last few months he was

ill, and he rarely appeared in public. This was pri-

marily a period of marking time, and little of note

happened in domestic or foreign policy during his

tenure. The rapid pace of personnel changes that

had begun under Andropov ground to a halt, as

did the few modest policy initiatives of his prede-

cessor. Mikhail Gorbachev’s active role during this

period was marked by intense political maneuver-

ing to succeed the frail Chernenko. When Cher-

nenko died in March 1985, the torch was passed

to the next generation with the selection of Gor-

bachev as his successor.

See also: AGITPROP; BREZHNEV, LEONID ILICH; COMMU-

NIST PARTY OF THE SOVIET UNION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Zemtsov, Ilya. (1989). Chernenko: The Last Bolshevik. New

Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Zlotnik, Marc. (1984). “Chernenko Succeeds.” Problems

of Communism 33 (2):17-31.

M

ARC

D. Z

LOTNIK

CHERNOBYL

The disaster at Chernobyl (Ukrainian spelling:

Chornobyl) on April 26, 1986 occurred as a result

of an experiment on how long safety equipment

would function during shutdown at the fourth re-

actor unit at Ukraine’s first and largest nuclear

power station. The operators had dismantled safety

mechanisms at the reactor to prevent its automatic

shutdown, but this reactor type (a graphite-

moderated Soviet RBMK) became unstable if operated

at low power. An operator error caused a power

surge that blew the roof off the reactor unit, re-

leasing the contents of the reactor into the atmos-

phere for a period of about twelve days.

The accident contaminated an area of about

100,000 square miles. This area encompassed

about 20 percent of the territory of Belarus; about

CHERNENKO, KONSTANTIN USTINOVICH

238

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

8 percent of Ukraine; and about 0.5-1.0 percent of

the Russian Federation. Altogether the area is ap-

proximately the size of the state of Kentucky or of

Scotland and Northern Ireland combined. The most

serious radioactive elements to be disseminated by

the accident were Iodine-131, Cesium-137, and

Strontium-90. The authorities contained the

graphite fire with sand and boron, and coal min-

ers constructed a shelf underneath it to prevent it

from falling into the water table.

After the accident, about 135,000 people were

evacuated from settlements around the reactor, in-

cluding the town of Pripyat (population 45,000),

the home of the plant workers and their families,

and the town of Chernobyl (population 10,000),

though the latter remained the center of the cleanup

operations for several years. The initial evacuation

zone was a 30-kilometer (about 18.6 miles) radius

around the destroyed reactor unit. After the spring

of 1989 the authorities published maps to show

that radioactive fallout had been much more ex-

tensive, and approximately 250,000 people subse-

quently moved to new homes.

Though the Soviet authorities did not release

accurate information about the accident, and clas-

sified the health data, under international pressure

they sent a team of experts to a meeting of the

IAEA (The International Atomic Energy Agency) in

August 1986, which revealed some of the causes

of the accident. The IAEA in turn was allowed to

play a key role in improving the safety of Soviet

RBMK reactors, though it did not demand the clo-

sure of the plant until 1994. A trial of Chernobyl

managers took place in 1987, and the plant direc-

tor and chief engineer received sentences of hard la-

bor, ten and five years respectively.

Chernobyl remains shrouded in controversy as

to its immediate and long-term effects. The initial

explosion and graphite fire killed thirty-one oper-

ators, firemen, and first-aid workers and saw sev-

eral thousand hospitalized. Over the summer of

1986 up until 1990, it also caused high casualties

among cleanup workers. According to statistics

from the Ukrainian government, more than 12,000

“liquidators” died, the majority of which were

young men between the ages of twenty and forty.

A figure of 125,000 deaths issued by the Ukrain-

ian ministry of health in 1996 appears to include

all subsequent deaths, natural or otherwise, of

those living in the contaminated zone of Ukraine.

According to specialists from the WHO (World

Health Organization) the most discernible health im-

pact of the high levels of radiation in the affected

territories has been the dramatic rise in thyroid gland

cancer among children. In Belarus, for example, a

1994 study noted that congenital defects in the ar-

eas with a cesium content of the soil of one–five

curies per square kilometer have doubled since

1986, while in areas with more than fifteen curies,

the rise has been more than eight times the norm.

Among liquidators and especially among evac-

uees, studies have demonstrated a discernible and

alarming rise in morbidity since Chernobyl when

compared to the general population. This applies

particularly to circulatory and digestive diseases,

and to respiratory problems. Less certain is the con-

cept referred to as “Chernobyl AIDS,” the rise of

which may reflect more attention to medical prob-

lems, better access to health care, or psychological

fears and tension among the population living in

contaminated zones. Rises in children’s diabetes and

anemia are evident, and again appear much higher

CHERNOBYL

239

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

An aerial view of the Chernobyl complex shows the shattered

reactor facility. A/P W

IDE

W

ORLD

. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

in irradiated zones. The connection between these

problems and the rise in radiation content of the

soil have yet to be determined.

To date, the rates of leukemia and lymphoma—

though they have risen since the accident—remain

within the European average, though in the upper

seventy-fifth percentile. One difficulty here is the

unreliability or sheer lack of reporting in the 1970s.

The induction period for leukemia is four to fifteen

years, thus it appears premature to state, as some

authorities have, that Chernobyl will not result in

higher rates of leukemia.

As for thyroid cancer, its development has been

sudden and rapid. As of 2003 about 2,000 children

in Belarus and Ukraine have contracted the disease

and it is expected to reach its peak in 2005. One

WHO specialist has estimated that the illness may

affect one child in ten living in the irradiated zones

in the summer of 1986; hence ultimate totals could

reach as high as 10,000. Though the mortality rate

from this form of cancer among children is only

about 10 percent, this still indicates an additional

1,000 deaths in the future. Moreover, this form of

cancer is highly aggressive and can spread rapidly

if not operated on. The correlation between thyroid

gland cancer and radioactive fallout appears clear

and is not negated by any medical authorities.

After pressure from the countries of the G7,

Ukraine first imposed a moratorium on any new

nuclear reactors (lifted in 1995) and then closed

down the Chernobyl station at the end of the year

2000. The key issue at Chernobyl remains the con-

struction and funding of a new roof over the de-

stroyed reactor, the so-called sarcophagus. The

current structure, which contains some twenty

tons of radioactive fuel and dust, is cracking and

is not expected to last more than ten years. There

are fears of the release of radioactive dust within

the confines of the station and beyond should the

structure collapse.

It is fair to say that the dangers presented by

former Soviet nuclear power stations in 2003 ex-

ceed those of a decade earlier. In the meantime,

some 3.5 million people continue to live in conta-

minated zones. From a necessary panacea, evacu-

ation of those living in zones with high soil

contamination today has become an unpopular and

slow-moving process. Elderly people in particular

have returned to their homes in some areas.

See also: ATOMIC ENERGY; BELARUS AND BELARUSIANS;

UKRAINE AND UKRAINIANS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Marples, David R. (1988). The Social Impact of the Cher-

nobyl Disaster. London: Macmillan.

Medvedev, Zhores. (1992). The Legacy of Chernobyl. New

York: Norton.

Petryna, Adriana. (2002). Life Exposed: Biological Citizens

after Chernobyl. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

Shcherbak, Yurii. (1988). Chernobyl: A Documentary Story.

London: Macmillan.

Yaroshinskaya, Alla. (1995). Chernobyl: The Forbidden

Truth. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

D

AVID

R. M

ARPLES

CHERNOMYRDIN, VIKTOR STEPANOVICH

(b. 1938), prime minister of the Russian Federation

from December 1992 to March 1998.

Trained in western Siberia as an engineer and

later an economist, Viktor Chernomyrdin alter-

nated between working as a communist party of-

ficial who monitored industrial enterprises and

actually running such enterprises in the gas in-

dustry. From 1978 he worked in the heavy indus-

try department of the party’s central apparatus in

Moscow, before becoming minister for the oil and

gas industries in 1985. In 1989 he was a pioneer

in turning part of his ministry into the state-owned

gas company Gazprom. He was the first chairman

of the board, and oversaw and benefited from its

partial privatization.

In 1990 he ran for the newly formed Russian

Republic (RSFSR) Congress of People’s Deputies, but

lost. In May 1992 President Yeltsin appointed him

a deputy prime minister of the newly independent

Russian Federation. In December, following an ad-

visory vote of the Congress in which he finished

second, a politically besieged Yeltsin made him

prime minister. Although a typical Soviet official

in most respects, Chernomyrdin gradually adapted

to free market processes. His concern not to move

too precipitately on economic reform enabled him,

with his powers of conciliation and compromise,

to appease the communists in some measure

throughout the 1990s. They looked to him to mod-

erate the radicalism of the “shock therapist” wing

of the government.

In the regime crisis of fall 1993, when, violat-

ing the Constitution, Yeltsin dispersed the parlia-

CHERNOMYRDIN, VIKTOR STEPANOVICH

240

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ment by military force amid much bloodshed,

Chernomyrdin supported Yeltsin without wavering.

His reputation suffered as a result of both this and

his poor handling of the financial crisis of October

1994 (Black Tuesday). Nonetheless, in April 1995 he

founded the first avowedly pro-government politi-

cal party, “Our Home is Russia”, which was covertly

funded by Gazprom. This was designed to create a

reliable, pro-Yeltsin bloc in the parliament elected in

December 1995. However, although Chernomyrdin

predicted that it would win almost a third of the

450 seats, in the event it got only 55, gaining the

support of a mere 10.1 percent of voters. Apart from

the fact that he was a weak leader, it had suffered

from public allegations by prominent figures that

his earlier leadership of Gazprom had enabled him

to accumulate personal wealth of some five billion

dollars. Apparently his denials did not convince

many voters. Later, the public documentation of

massive corruption in his government did not evoke

even pro forma denials.

In March 1998 Yeltsin dismissed him without

explanation, only to nominate him as acting prime

minister the following August. However, the par-

liament twice refused to confirm him, seeing him

as one of the individuals most responsible for the

financial collapse of that month. So the flounder-

ing president withdrew his nomination. However,

Yeltsin named him the next spring as his special

representative to work with NATO on resolving the

Yugoslav crisis over Kosovo.

In 1999 and 2000 Chernomyrdin chaired the

Gazprom Council of Directors, and from 1999 to

2001 he was a parliamentary deputy for the pro-

Kremlin party Unity. In 2001 President Putin made

him ambassador to Ukraine. Here he supervised a

creeping Russian takeover of the Ukrainian gas in-

dustry that stemmed from Ukraine’s inability to

finance its massive gas imports from Russia.

See also: ECONOMY, POST-SOVIET; OCTOBER 1993 EVENTS;

OUR HOME IS RUSSIA PARTY; PRIVATIZATION; YELTSIN,

BORIS NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Reddaway, Peter, and Glinski, Dmitri. (2001). The Tragedy

of Russia’s Reforms: Market Bolshevism Against Democ-

racy. Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press.

Shevtsova, Lilia. (1999). Yeltsin’s Russia: Myths and Re-

ality. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for In-

ternational Peace.

P

ETER

R

EDDAWAY

CHERNOV, VIKTOR MIKHAILOVICH

(1873–1952), pseudonyms: ‘Ia. Vechev’, ‘Gardenin’,

‘V. Lenuar’; leading theorist and activist of the So-

cialist Revolutionary Party.

Viktor Chernov was born into a noble family

in Samara province. He studied at the Saratov gym-

nasium, but was transferred to the Derpt gymna-

sium in Estonia as a result of his revolutionary

activity. In 1892 Chernov joined the law faculty at

Moscow University, where he was active in the

radical student movement. He was first arrested in

April 1894 and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul

Fortress for six months. Chernov was exiled to

Kamyshin in 1895, but was transferred to Saratov

and then to Tambov because of poor health. He

married Anastasia Nikolaevna Sletova in 1898. In

the same year, he organized the influential “Broth-

erhood for the Defense of People’s Rights” in Tam-

bov, a revolutionary peasants’ organisation.

CHERNOV, VIKTOR MIKHAILOVICH

241

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

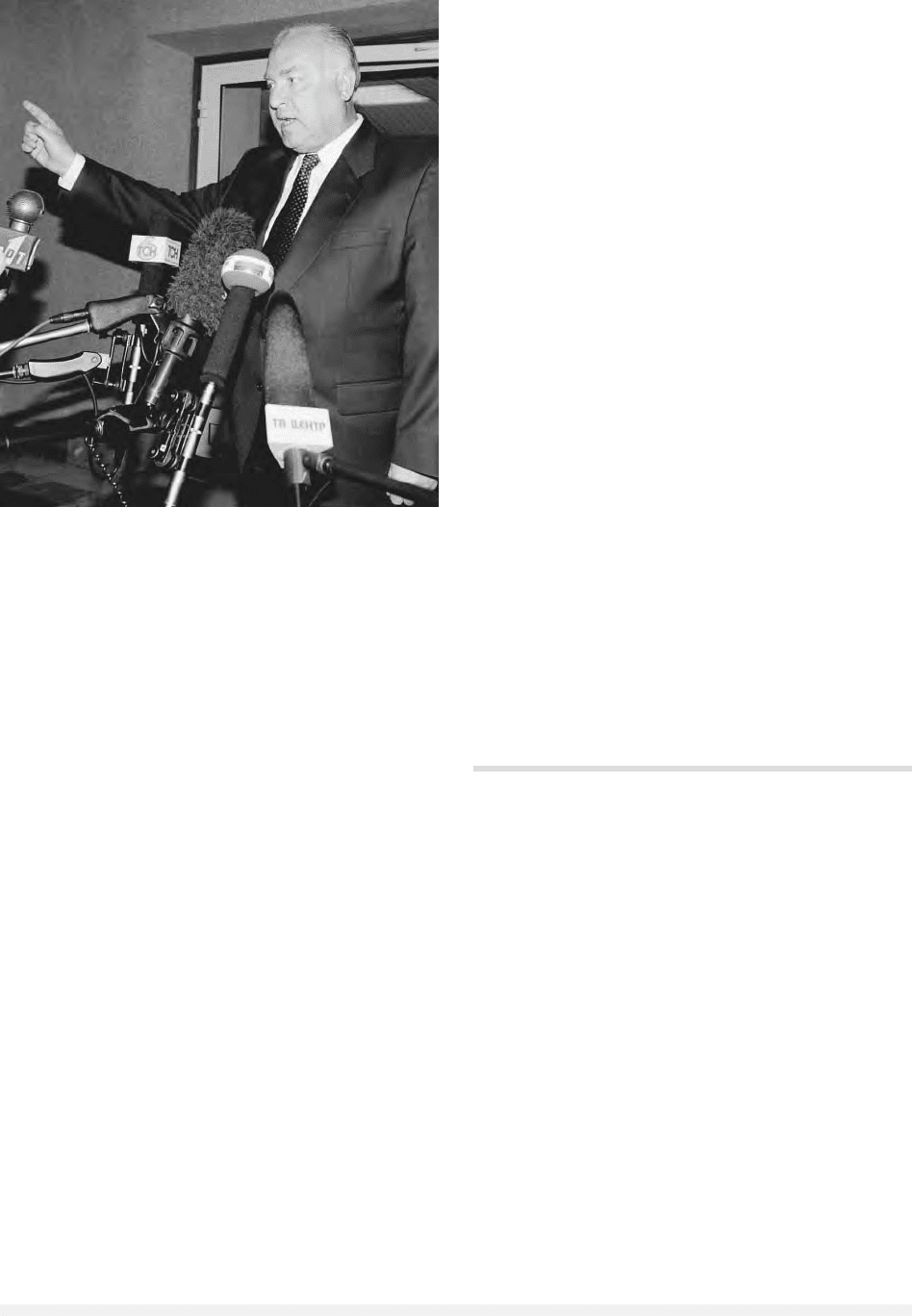

Viktor Chernomyrdin speaks to journalists after the Duma

rejected Yeltsin’s attempts to reappoint him prime minister in

1998. © S

ACHA

O

RLOV

/G

ETTY

I

MAGES

In 1899 Chernov left Russia, and for the next

six years he worked for the revolutionary cause in

exile. He joined the newly formed Socialist Revolu-

tionary Party in 1901, and from 1903 he was a

central committee member. His role in the party

was predominantly as a political theorist and

writer. He formulated the party’s philosophy

around a blending of Marxist and Populist ideas,

propounding that Russia’s communal system of-

fered a “third way” to the development of social-

ism. He reluctantly supported the use of terror as

a means of advancing the revolutionary cause.

Chernov returned to St. Petersburg in October

1905, and proposed that the party follow a mod-

erate line, suspending terrorist activity and oppos-

ing further strike action. In July 1906 he again left

Russia, this time for Finland. He continued his rev-

olutionary work abroad, not returning to Russia

until April 1917. Chernov joined the first coalition

Provisional Government as Minister for Agriculture

in May 1917, despite misgivings about socialist

participation in the Provisional Government. His

three months in government raised popular expec-

tations about an imminent land settlement, but his

tenure as minister was marked by impotency. The

Provisional Government refused to sanction his

radical proposals for reform of land use.

Chernov struggled to hold the fractured Social-

ist Revolutionary Party together, and stepped down

from the Central Committee in September 1917. He

was made president of the Constituent Assembly,

and after the Constituent Assembly’s dissolution,

was a key figure in leftist anti-Bolshevik organiza-

tions, including the Komuch. He believed that the So-

cialist Revolutionary Party needed to form a “third

front” in the civil war period, fighting for democ-

racy against both the Bolsheviks and the Whites.

He left Russia in 1920, and was a passionate con-

tributor to the emigré anti-Bolshevik movement

until his death in 1952 in New York. Chernov was

a gifted intellectual and theorist who ultimately

lacked the ruthless single-mindedness required of a

revolutionary political leader.

See also: SOCIALIST REVOLUTIONARIES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Burbank, Jane. (1985). “Waiting for the People’s Revo-

lution: Martov and Chernov in Revolutionary Rus-

sia, 1917–1923.” Cahiers du monde russe et sovietique

26(3–4):375–394.

Chernov, Victor Mikhailovich. (1936). The Great Russian

Revolution. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Melancon, Michael. (1997). “Chernov.” In Critical Com-

panion to the Russian Revolution, 1914–1921, ed. Ed-

ward Acton, Vladimir Chernaiev, and William G.

Rosenberg. London: Arnold.

S

ARAH

B

ADCOCK

CHERNUKHA

Pessimistic neo-naturalism and muckraking during

and after glasnost.

Chernukha is a slang term popularized in the

late 1980s, used to describe a tendency toward un-

relenting negativity and pessimism both in the arts

and in the mass media. Derived from the Russian

word for “black” (cherny), chernukha began as a

perestroika phenomenon, a rejection of the enforced

optimism of official Soviet culture. It arose simul-

taneously in three particular areas: “serious” fic-

tion (published in “thick” journals such as Novy

mir), film, and investigative reporting. One of the

hallmarks of Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost was the

open discussion of the misery and violence that was

a part of everyday Soviet life, transforming the

form and content of the nation’s news coverage. In

journalism, chernukha was most clearly incarnated

in Alexander Nevzorov’s evening television pro-

gram “600 Seconds,” which exposed the Soviet

viewing audience to some of its first glimpses into

the lives of prostitutes and gangsters, never shy-

ing away from images of graphic violence.

In literature and film, chernukha refers to the

naturalistic depiction of and obsession with bodily

functions, sexuality, and often sadistic violence,

usually at the expense of more traditional Russian

themes, such as emotion and compassion. The most

famous examples of artistic chernukha include

Sergei Kaledin’s 1987 novel The Humble Cemetery,

which tells a story about gravediggers in Moscow,

and Vasilii Pichul’s 1988 Little Vera, a film about

a dysfunctional family, complete with alcoholics,

knife fights, arrests, and virtually nonstop shout-

ing. Also emblematic was Stanislav Govorukhin’s

1990 documentary This Is No Way to Live, whose

very title sums up the general critical thrust of

chernukha in the glasnost era.

Often condemned by critics across the ideolog-

ical spectrum as “immoral,” chernukha actually

played an important part in the shift in values and

in the ideological struggles concerning the coun-

try’s legacy and future course. Intentionally or not,

CHERNUKHA

242

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY