Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

persuasiveness to objections from American con-

servatives. Soviet backing for the 1973 attack on

Israel and for armed takeovers in Africa discredited

the U.S. public’s faith in the sincerity of the Soviet

Union’s peaceful intentions. By 1979 the effort to

occupy Afghanistan, in a reprise of the Czechoslo-

vak action, landed the Soviet army in a war it

proved incapable of winning while compelling Pres-

ident Jimmy Carter to abandon arms control ne-

gotiations and to withdraw from the Moscow

Olympics. In the summer of 1980 Polish strikers

formed the movement known as Solidarity,

demonstrating to Soviet officials that Brezhnev had

bet wrongly on the combination of military ex-

pansion, improved food supplies, and increases in

the availability of consumer goods to secure the al-

legiance of workers in communist-ruled states.

Under the strain of personal responsibility for

preserving the Soviet order, Brezhnev’s health de-

teriorated rapidly after the middle 1970s. In 1976

he briefly suffered actual clinical death before be-

ing resuscitated; as a result, he was constantly ac-

companied by modern resuscitation technology

bought from the West (which had to be used more

than once). Ill health made Brezhnev lethargic; it is

unclear, however, what even a more energetic

leader could have done to solve the Soviet Union’s

problems. Despite Brezhnev’s torpor, his colleagues

within the Politburo and his loyalists, whom he

had placed in key posts throughout the apex of the

Soviet party and state, continued to see their per-

sonal fortunes tied to his leadership. He remained

in power until a final illness, which is thought to

have been brought on by exposure to inclement

weather during the 1982 celebration of the Octo-

ber Revolution anniversary.

LATER REAPPRAISAL

For Gorbachev and his adherents, Brezhnev came

to personify everything that was wrong with the

Soviet regime. The popularity of Gorbachev’s pro-

gram among Western specialists, and the interest

generated by the new leader’s dynamism after the

boring stasis of Brezhnev’s later years, precluded a

reappraisal of Brezhnev’s career until 2002, when

a group of younger scholars picked up on Brezh-

nev’s growing popularity among certain members

of the Russian population. These people remem-

bered with fondness Brezhnev’s alleviation of their

or their parents’ poverty, a relief made all the more

striking by the extreme impoverishment experi-

enced by many in the post-Soviet era. This re-

assessment may appear unwarranted to those who

prize political liberty above marginal increments in

material consumption.

See also: BREZHNEV DOCTRINE; CONSTITUTION OF 1977;

DÉTENTE; KHRUSHCHEV, NIKITA SERGEYEVICH; KOSY-

GIN, ALEXEI NIKOLAYEVICH; POLITBURO

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, Richard D., Jr. (1993). Public Politics in an Au-

thoritarian State: Making Foreign Policy in the Brezh-

nev Politburo. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Bacon, Edwin, and Sandle, Mark, eds. (2002). Brezhnev

Reconsidered. Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave

Macmillan.

Breslauer, George W. (1982). Khrushchev and Brezhnev as

Leaders: Building Authority in Soviet Politics. London:

George Allen and Unwin, Publishers.

Brezhneva, Luba. (1995). The World I Left Behind, tr. by

Geoffrey Polk. New York: Random House.

Dawisha, Karen. (1984). The Kremlin and the Prague

Spring. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Dornberg, John. (1974). Brezhnev: The Masks of Power.

New York: Basic Books.

Institute of Marxism-Leninism, CPSU Central Commit-

tee. (1982). Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev: A Short Biography.

Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press.

R

ICHARD

D. A

NDERSON

J

R

.

BRODSKY, JOSEPH ALEXANDROVICH

(1940–1996), poet, translator.

Joseph Alexandrovich Brodsky left school at

the age of fifteen, and worked in many professions,

including factory worker, morgue worker, and

ship’s boiler, as well as assisting on geological ex-

peditions. During his early years, Brodsky studied

foreign languages (English and Polish). His first

foray into poetry occurred in 1957 when Brodsky

became acquainted with the famous Russian poet

Anna Akhmatova, who praised the creativity of the

budding poet. In the 1960s Brodsky worked on

translating, into Russian, poetry of Bulgarian,

Czech, English, Estonian, Georgian, Greek, Italian,

Lithuanian, Dutch, Polish, Serbian-Croatian, and

Spanish origins. His translations opened the works

of authors such as Tom Stoppard, Thomas

Wentslowa, Wisten Oden, and Cheslaw Milosh to

Russian readers; John Donne, Andrew Marwell,

and Ewrypid were newly translated.

BRODSKY, JOSEPH ALEXANDROVICH

173

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

On February 12, 1964, Brodsky was arrested

and charged with parasitism and sentenced to five

years deportation. In 1965, after serving eighteen

months in a labor camp in northern Russia,

protests in the USSR and abroad prompted his re-

turn from exile.

During the summer of 1972, Brodsky emi-

grated to the United States and became a citizen in

1980. Before his departure from the Soviet Union,

he published eleven poems during the period from

1962 to 1972.

By the 1960s Brodsky was still relatively un-

known in the West. “Cause of Brodsky” found

scant exposure on the pages of the emigrant press

(Russkaya mysl, Grani, Wozdushnye Puti, Posev, etc.).

Brodsky’s first collection of poems was released by

the Ardis publishing house in 1972. Throughout

the 1970s Brodsky collaborated as a literary critic

and essay writer in the New Yorker and the New York

Review of Books, and gained a wider readership in

the United States.

Brodsky taught at several colleges and univer-

sities, including Columbia University and Mount

Holyoke College. In 1987 he won the Nobel prize

for literature. He served as Poet Laureate of the

United States from 1991 to 1992.

Brodsky died in 1996 of a heart attack in his

Brooklyn apartment.

See also: DISSIDENT MOVEMENT; INTELLIGENTSIA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bethea, David M. (1994). Joseph Brodsky and the Creation

of Exile. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Loseff, Lev. (1991). “Home and Abroad in the Works of

Brodskii.” In Under Eastern Eyes: The West as Reflected

in Recent Russian Emigre Writing, ed. Arnold

McMillin. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan Press with

the SSEES University of London.

Loseff, Lev, and Polukhina, Valentina, eds. (1990). Brod-

sky’s Poetics and Aesthetics. London: Macmillan.

Polukhina, Valentina. (1989). Joseph Brodsky: A Poet for

Our Time. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Polukhina, Valentina. (1992). Brodsky through the Eyes of

His Contemporaries. London: Macmillan Press.

Polukhina, Valentina. (1944). “The Myth of the Poet and

the Poet of the Myth: Russian Poets on Brodsky.” In

Russian Writers on Russian Writers, ed. Faith Wigzell.

Oxford: Berg.

M

ARIA

E

ITINGUINA

BRUCE, JAMES DAVID

(1669–1735), one of Peter the Great’s closest ad-

visers.

A man of many métiers, James David Bruce

(“Yakov Vilimovich Bruce”) served Russia over the

course of his lifetime as general, statesman, diplo-

mat, and scholar. Bruce participated in both the

Crimean and Azov expeditions. In 1698 he traveled

to Great Britain, where he studied several subjects,

including Isaac Newton’s then-avant-garde philos-

ophy of optics (i.e., that light itself is a heteroge-

neous mixture of differently refrangible rays) and

gravity (i.e., that celestial bodies follow the laws of

dynamics and universal gravitation). Upon return

to Russia, Bruce enthusiastically established the

first observatory in his native country.

In 1700, at the age of thirty-one, Bruce achieved

the rank of major general and commanded forces

in the Great Northern War against Sweden. After

a humiliating defeat by the Swedes near Narva on

November 19, 1700, after which Peter reputedly

wept, Peter vowed to improve his army and defeat

Sweden in the future. He concluded that a modern

army needed a disciplined infantry equipped with

the latest artillery (rifles). This infantry was sup-

posed to advance while firing and then charge with

fixed bayonets. (The Russian army had consisted

mostly of cavalry, its officer corps composed of for-

eign mercenaries.)

Bruce was one of the new trainers Peter em-

ployed to improve the quality of the Russian army.

On July 8, 1709, Russian artillery defeated Charles’s

army and sent it into retreat. That year Bruce was

awarded the Order of St. Andrew for his decisive

role in reforming artillery as master of ordnance in

the Great Northern War. In 1712 and 1713 Bruce

headed the allied artillery of Russia, Denmark, and

Poland-Saxony in Pomerania and Holstein. In 1717

he became a senator and president of Colleges of

Mines and Manufacture. He was also placed in

charge of Moscow print and St. Petersburg mint.

As first minister plenipotentiary at the Aland and

Nystad congresses, Bruce negotiated and signed the

Russian peace treaty with Sweden in 1721, the

same year he became count of the Russian Empire.

He retired in 1726 with the rank of field marshal.

Bruce corresponded with Jacobite kinsmen and

took pride in his Scottish ancestry. He owned a li-

brary of books in fourteen languages and was

known by many as the most enlightened man in

Russia.

BRUCE, JAMES DAVID

174

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

See also: GREAT NORTHERN WAR; PETER I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chambers, Robert, and Thomson, Thomas. (1996). The

Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Scotsmen. Bristol,

UK: Thoemmes Press.

Fedosov, Dmitry. (1996). The Caledonian Connection: Scot-

land-Russia Ties, Middle Ages to Early Twentieth Cen-

tury. Old Aberdeen, Scotland: Centre for Scottish

Studies, University of Aberdeen.

Fedosov, Dmitry. (1992). “The First Russian Bruces.” In

The Scottish Soldier Abroad, ed. Grant G. Simpson. Ed-

inburgh, Scotland: John Donald.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

BRUSILOV, ALEXEI ALEXEYEVICH

(1853–1926), Russian and Soviet military figure,

World War I field commander.

Born in Tiflis (Tbilisi), Alexei Alexeyevich

Brusilov entered military service in 1871, gradu-

ated from the Corps of Pages in 1872, and com-

pleted the Cavalry Officers School in 1883. As a

dragoon officer during the Russo-Turkish War of

1877–1878, he fought with distinction in the

Trans-Caucasus. Between 1883 and 1906 he served

continuously at the Cavalry School, eventually be-

coming its commandant. Although he did not at-

tend the General Staff Academy or serve in the

Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), he rose during

the period from 1906 to 1914 to repeated com-

mand assignments, including two postings as a

corps commander. At the outset of World War I

his Eighth Army won important successes during

its advance into Galicia and the Carpathians. Be-

tween May and July of 1916, Brusilov’s South-

western Front conducted one of the most

significant ground offensives of World War I, in

which his troops broke through the Austro-

Hungarian defenses to occupy broad expanses of

Volynia, Galicia, and Bukovina.

As supreme commander (May–July 1917) of

the Russian armies after the February Revolution,

Brusilov presided over the ill-fated summer offen-

sive of 1917. After the October Revolution, unlike

many of his colleagues, he refused to join the

counterrevolutionary cause. Instead, at the outset

of the war with Poland in 1920, he entered the Red

Army, serving the new Soviet regime in various

military capacities (including inspector general of

cavalry) until his death. A consummate cavalryman

and a flexible military professional, Brusilov saw

his primary career obligation as patriotic service to

his country, whether tsarist or revolutionary.

See also: FEBRUARY REVOLUTION; OCTOBER REVOLUTION;

RUSSO-TURKISH WARS; WORLD WAR I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Wildman, Allan K. (1980). The End of the Russian Imper-

ial Army. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

B

RUCE

W. M

ENNING

BRYUSOV, VALERY YAKOVLEVICH

(1873–1924), poet, novelist, playwright, critic,

translator.

Born in Moscow, Valery Bryusov was an early

proponent of Symbolism in Russia. As editor of the

almanac Russkie Simvolisty (Russian symbolists,

1894–1895), Bryusov presented the first articula-

tion of the tenets of Modernism in Russia.

Bryusov’s poetry in this almanac illustrated the

points set forth in the declarations, with elements

of decadence, synaesthesic imagery, and Symbolist

motifs.

In 1899 Sergei Polyakov invited Bryusov to

participate in the founding of the Skorpion Pub-

lishing House. In addition to publishing the works

of leading Symbolists, Skorpion Publishing House

in 1904 sponsored the literary journal Vesy (The

scales), which became the leading forum for writ-

ers of that time. By 1906 Bryusov became in-

creasingly critical of writers and poets with whom

he disagreed, instituting a vitriolic polemic against

the proponents of mystical anarchism and the so-

called younger generation of Symbolists, especially

those involved with the journal Zolotoye runo (The

golden fleece).

In the 1910s Bryusov continued to work in all

aspects of artistic culture, writing plays, a novel,

and literary criticism, and engaging the Futurists

in a lively debate on poetry. In 1913 Bryusov wrote

a book of poems under the pseudonym Nelli, com-

bining an ironic life story of a tragic poet with ex-

perimental, Futurist-inspired poems. The ironic

mystification met with consternation and derision

by the Futurists.

BRYUSOV, VALERY YAKOVLEVICH

175

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Bryusov was an enthusiastic supporter of the

Russian Revolution, believing it to be a transfor-

mative event in history. Bryusov became a mem-

ber of the Communist Party in 1920 and was active

in Narkompros (The People’s Commissariat for En-

lightenment), serving as head of its printing and li-

brary divisions. In 1921 Bryusov organized the

Higher Institute of Literature and Art and was the

director until his death.

See also: FUTURISM; SILVER AGE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Pyman, Avril. (1994). A History of Russian Symbolism.

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rice, Martin. (1975). Valery Briusov and the Rise of Russ-

ian Symbolism. Ann Arbor, MI: Ardis.

M

ARK

K

ONECNY

BUCHAREST, TREATY OF

The Treaty of Bucharest brought the Turkish war

of 1806–1812 to an end. Having advanced the

Russian frontier to the Dniester River in 1792,

Catherine the Great intended to include Moldavia

and Wallachia within a Dacian Kingdom under one

of her favorites. The immediate occasion for the

war, however, were the intrigues of Napoleon’s

ambassador at Constantinople, General Horace Se-

bastiani, who dismissed two pro-Russian princes in

violation of protective rights obtained by the tsar

in 1802. Catherine’s grandson Alexander I opened

hostilities in 1806 when sixty thousand men, ini-

tially led by General Mikhail Kamensky and later

by Mikhail Kutuzov, crossed the Danube. This cam-

paign proved desultory, even though in 1807 a

Russian administration replaced the Greek Princes

nominated by the Turks. When Napoleon met Tsar

Alexander I at Tilsit (1807) and later at Erfurt

(1808) to partition the Ottoman Empire, the for-

mer was willing to concede control of both princi-

palities to Russia but was unwilling to give up

Constantinople, the ultimate prize the French em-

peror had sought. In consequence, the good rela-

tions between the two emperors deteriorated. When

it became apparent that Napoleon was planning a

coalition for an invasion of Russia in 1812, the tsar,

unwilling to fight Turks and French on two fronts,

sent a delegation under General Count Alexander

de Langeron, General Joseph Fonton, and the Russ-

ian ambassador to Constantinople, Count Andrei

Italinsky, to negotiate with the Turks in Bucharest.

The latter were represented by the Grand Vizier

Ahmed Pasha, the Chief Interpreter (Drogman)

Mehmed Said Galid Effendi, and his colleague

Demetrius Moruzi. They met at the inn of a

wealthy Armenian Mirzaian Manuc. The talks were

confrontational: the Turks unwilling to cede one

inch of territory, the Russians demanding the

whole province of Moldavia. In the end, Sir Strat-

ford Canning, a young English diplomat who re-

placed the vacationing English ambassador Sir

Robert Adair, made a diplomatic debut that earned

him a brilliant career on the eve of the Crimean

War. He argued that the Turks lacked the resources

to continue the war, while the Russians needed the

troops of Admiral Pavel Chichagov (taking over Ku-

tuzov’s command) who returned to Russia to face

the Napoleonic onslaught. In the end, Canning cited

an obscure article of the Treaty of Tilsitt (article

12) negotiated by the Russian Chancelor Peter

Rumyantsev as an acceptable compensation. This

territory, misnamed by the Russians “Bessarabia”

(a name derived from the first Romanian princely

dynasty of Wallachia, which controlled only Mol-

davia’s southern tier), advanced the Russian fron-

tier from the Dniester to the Pruth and the northern

mouth of the Danube (Kilia). This represented a

gain of 500,000 people of various ethnic stock,

45,000 kilometers, five fortresses, and 685 villages.

By sacrificing the coveted prize of both principali-

ties and withdrawing the army from Turkey, the

tsar was able to confront Napoleon on a single

front. This, according to General Langeron, made

a difference at the battle of Borodino (1812).

Not content at having saved most of the

Moldo-Wallachian provinces, the Turks, who had

no legal right to a territory over which they exer-

cised de jure suzerainty, vented their frustration by

hacking their chief interpreter Moruzi to pieces and

hanging his head at the Seraglio. From a Roman-

ian standpoint, the cession of Bessarabia to Russia

in 1812 marked a permanent enstrangement in

Russo-Romanian relations, which continued in the

early twenty-first century with the creation of a

Moldavian Republic within the Russian Common-

wealth.

See also: ROMANIA, RELATIONS WITH; RUSSO-TURKISH

WARS; TURKEY, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dima, Nicholas. (1982). Bessarabia and Bukovina: The So-

viet Romanian Territorial Dispute. New York and

Boulder, CO: East European Monographs.

BUCHAREST, TREATY OF

176

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Florescu, Radu. (1992). The Struggle Against Russia in the

Romanian Principalities (1821–1854). Munich: Ro-

manian Academic Society.

Jewsbury, George F. (1976). The Russian Annexation of

Bessarabia 1174–1828. New York: East European

Monographs.

R

ADU

R. F

LORESCU

BUDENNY, SEMEON MIKHAILOVICH

(1883–1973), marshal of the Soviet Union.

Born near Rostov-on-Don to non-Cossack par-

ents, Budenny served in Cossack regiments dur-

ing the Russo-Japanese War and in World War I

(receiving four St. George’s Crosses for bravery as

a noncommissioned officer). Having joined the

Bolsheviks in 1918 and being an accomplished

horseman, he organized cavalry detachments

around Tsaritsyn during the civil war before creat-

ing and commanding the legendary First Cavalry

Army in actions against the Whites and the Poles.

From 1924 to 1937 he served as Inspector of Cav-

alry, reaching the exalted rank of marshal in

1935. He actively helped purge the Red Army in

1937, as commander of Moscow military district,

but the Nazi invasion revealed him to be com-

pletely out of his depth in modern, mechanized

warfare. As commander-in-chief of the South-

West Direction of the Red Army in Ukraine and

Bessarabia, Budenny was largely responsible for

the disastrous loss of Kiev in August 1941. Prob-

ably only his closeness to Josef Stalin and Kliment

Voroshilov (a legacy of his civil war service at

Tsaritsyn/Stalingrad) saved him from execution.

Instead, he was removed from frontline posts in

September 1941, becoming commander of cavalry

in 1943 and deputy minister of agriculture, in

charge of horse breeding. He was a member of the

Central Committee of the Communist Party of the

Soviet Union from 1939 to 1952. Virtually une-

ducated but with enormous charisma (and even

more enormous moustaches), Budenny became a

folklore figure, a decorative accoutrement to the

grey men of the postwar Soviet leadership, and a

museum piece. Present at all parades and state oc-

casions, bedecked with medals and orders, he was

a living relic of the heroic days of the Civil War.

Several thousand streets, settlements, and collec-

tive farms were named in his honor, as was a

breed of Russian horses. He lived out his last years

quietly in Moscow, pursuing equestrian interests.

See also: CIVIL WAR OF 1917–1922; COSSACKS; WORLD

WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Budyonny, Smeyon. (1972). The Path of Valour. Moscow:

Progress Publishers.

Vitoshnov, Sergei. (1998). Semen Budennyi. Minsk:

Kuzma.

J

ONATHAN

D. S

MELE

BUKHARA

Established in the sixteenth century, the Bukharan

khanate maintained commercial and diplomatic

contact with Russia. Territorial conflicts with

neighboring Khiva and Kokand prevented forma-

tion of a united front against Russia’s encroach-

ment in the mid-nineteenth century.

War from 1866 to 1868 ended with Russia’s

occupation of the middle Zarafshan River valley,

including Samarkand, and the grant of trading

privileges to Russian merchants. The 1873 treaty

opened the Amu Darya to Russian ships; pledged

the emir to extradite fugitive Russians and abolish

the slave trade; and ceded Samarkand, leaving Rus-

sia in control of the water supply of the lower

Zarafshan, including that of the capital.

Bukhara as a Russian protectorate was slightly

larger than Great Britain and Northern Ireland,

with a population of two and a half to three mil-

lion. Urban residents comprised 10 to 14 percent

of the total; the largest town was the capital, with

population of 70,000 to 100,000. The dominant

ethnic group was the Uzbeks (55–60%), followed

by the Tajiks (30%) and the Turkmen (5–10%).

Bukhara was ruled by an hereditary autocratic

emir. Muzaffar ad-Din (1860–1885) was succeeded

by his son Abd al-Ahad (1885–1910) and the lat-

ter’s son Alim (1910–1920).

In reducing Bukhara to a wholly dependent but

internally self-governing polity, Russia aimed to

acquire a stable frontier in Central Asia, to prevent

Britain alone from filling the political vacuum be-

tween the two empires, and to avoid the burdens

of direct rule. This policy succeeded for half a cen-

tury. After 1868 no emir contemplated using his

army against his protector; in 1873 Britain and

Russia recognized the Amu Darya as separating a

Russian sphere of influence (Bukhara) from a

British sphere (Afghanistan); and the emirs main-

tained sufficient domestic order.

BUKHARA

177

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Russia’s impact increased over the years. In the

mid-1880s Bukhara’s capital was connected by

telegraph with Tashkent; a Russian political

agency was established; and the Central Asian Rail-

road was built across the khanate. In the latter part

of the 1880s three Russian urban enclaves, and a

fourth at the turn of the century, were established;

by the eve of World War I they contained from

thirty-five to forty thousand civilians and soldiers.

In 1895 the khanate was included in Russia’s cus-

toms frontier, and Russian troops and customs

officials were stationed along the border with

Afghanistan.

Russo-Bukharan trade increased sixfold from

the coming of the railroad to 1913. Production of

cotton, which represented three-fourths of the

value of Bukhara’s exports to Russia, expanded two

and a half times between the mid-1880s and the

early 1890s, grew slowly thereafter, but doubled

during World War I. Unlike Turkestan, the khanate

remained self-sufficient in foodstuffs.

After the fall of the tsarist regime, Emir Alim

resisted pressure for reforms from the Provisional

Government and the Bukharan Djadids (moderniz-

ers). With the Bolsheviks in control of the railroad,

the Russian enclaves, and the water supply of his

capital from December 1917, the emir maintained

strained but correct relations with the Soviet gov-

ernment during the Russian civil war.

In the late summer of 1920 the Red Army over-

threw Alim. A Bukharan People’s Soviet Republic,

led by Djadids, was proclaimed. Russia renounced

its former rights, privileges, and property in

Bukhara, but controlled the latter’s military and

economic affairs. The Djadids were purged in 1923,

and the following year the Bukharan People’s So-

viet Republic was divided along ethnic lines between

the newly formed Uzbek and Turkmen Soviet So-

cialist Republics.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; KHIVA; NATIONALITIES POLI-

CIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST;

TURKMENISTAN AND TURKMEN; UZBEKISTAN AND

UZBEKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Becker, Seymour. (1968). Russia’s Protectorates in Central

Asia: Bukhara and Khiva, 1865–1924. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

S

EYMOUR

B

ECKER

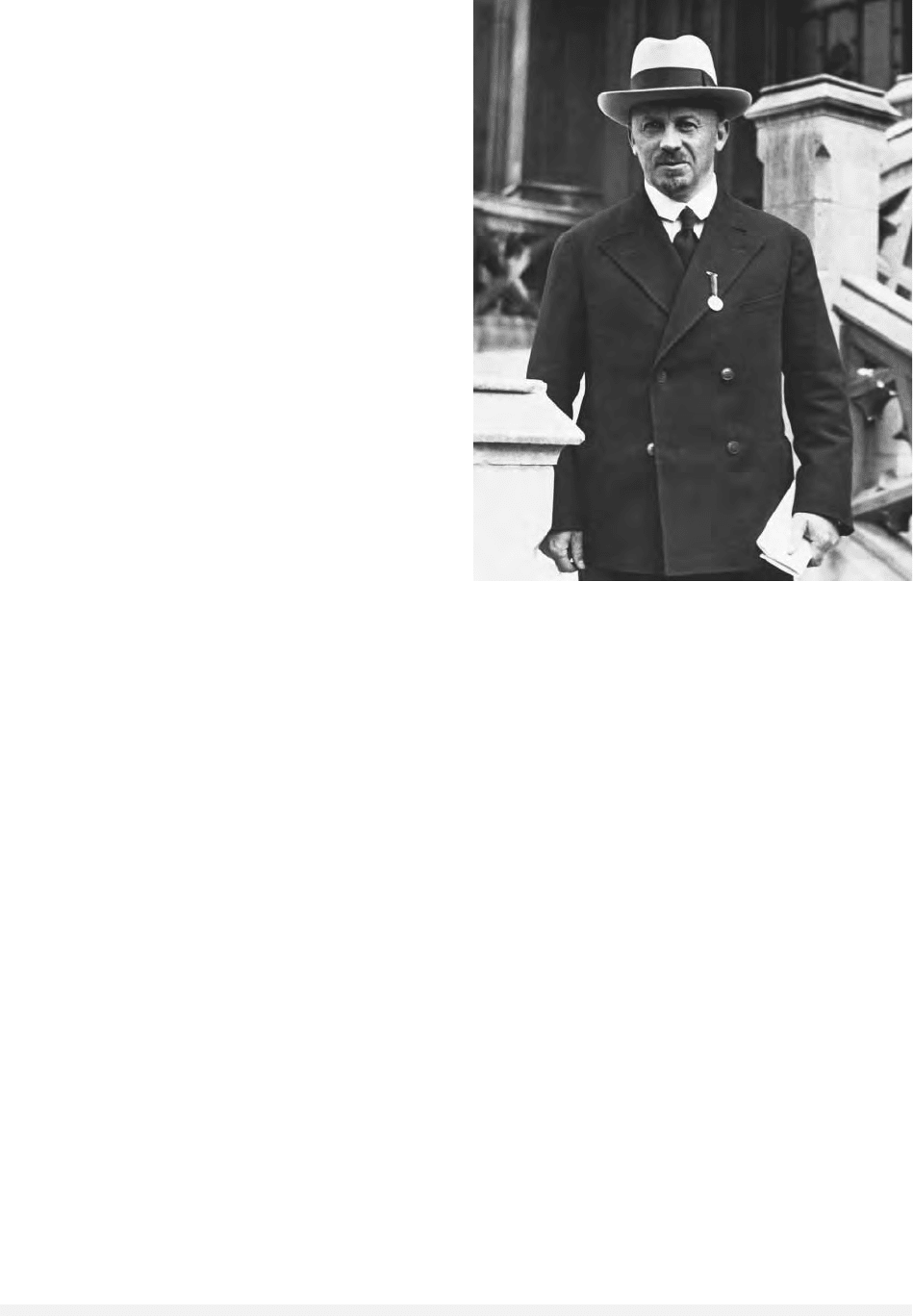

BUKHARIN, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH

(1888–1938), old Bolshevik economist and theo-

retician who was ousted as a Rightist in 1929 and

executed in 1938 for treason after a show trial.

The son of Moscow schoolteachers, raised in

the spirit of the Russian intelligentsia, Nikolai

Ivanovich Bukharin was a broadly educated and

humanist intellectual. Radicalized as a high school

student during the 1905 Revolution, he was drawn

to the Bolshevik faction, which he formally joined

in 1906. He enrolled at Moscow University in 1907

to study economics, but academics took second

place to party activity. He rose rapidly in the

Moscow Bolshevik organization, was arrested sev-

eral times, and in 1911 fled abroad, where he re-

mained until 1917. These six years of emigration

strengthened Bukharin’s internationalism; he ma-

tured as a Marxist theorist and writer and became

known as a radical voice in the Bolshevik party.

After a year in Germany, he went to Krakow in

1912 to meet Vladimir Lenin, who invited him to

write for the party’s publications. Bukharin settled

in Vienna, where he studied and drafted several the-

oretical works. Expelled to Switzerland at the be-

ginning of World War I, he supported Lenin’s

radical antiwar platform, continuing his activities

in Scandinavia and then New York City.

When revolution broke out in Russia in early

1917, Bukharin hastened home. Arriving in May,

he immediately took a leading role in the Moscow

Bolshevik organization, which was dominated by

young radicals. His militant stance brought him

close to Lenin. In July 1917 he was elected a full

member of the Central Committee, and in Decem-

ber he was appointed editor of the party newspaper,

Pravda. Bukharin opposed the peace negotiations

with the Central Powers at Brest-Litovsk and headed

the Left Communists who called for a revolution-

ary war against capitalism; later he also opposed

Lenin’s view that state capitalism would be a step

forward for Russia. In mid-1918, ending his oppo-

sition, he resumed his party positions as the bur-

geoning civil war led to war communism and

rebellion by the Left Socialist Revolutionaries. In

1919, when a five-man Politburo was formally es-

tablished, Bukharin became one of three candidate

members and also became deputy chairman of the

newly established Comintern. Serving in various ca-

pacities during the civil war, Bukharin also pub-

lished extensively: including Imperialism and World

Economy (1918), the popularizing and militant ABC

of Communism (1920, with Yevgeny Preobrazhen-

BUKHARIN, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH

178

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

sky); Economics of the Transition Period (1920),

which celebrated the statization of the economy un-

der War Communism but also began to explore

how to build a socialist society after the revolution;

and Historical Materialism (1921), a major analysis

of Marxism in the twentieth century.

After Lenin introduced the New Economic Pol-

icy in 1921, debate swirled around the question of

the relative importance that should be accorded in-

dustry and agriculture to achieve economic devel-

opment within the framework of a socialist

economy. Leon Trotsky and the Left Opposition fa-

vored rapid industrialization at the expense of agri-

culture, in what Preobrazhensky termed “primitive

socialist accumulation.” Bukharin, disavowing the

illusions of War Communism, emphasized the need

to find an evolutionary path to socialism based on

a strong alliance with Russia’s peasant majority

and invoked Lenin’s last writings to legitimize this

position. He argued that forcibly appropriating

agricultural surpluses would ultimately lead to the

disintegration of agriculture because peasants

would no longer have an incentive to produce.

While agreeing that industrialization was ab-

solutely critical for the construction of socialism,

he favored a gradual approach. Bukharin’s path to

socialism relied upon a growing consumer market,

possible only if there were private merchants to

contribute to the growth of domestic trade. He ar-

gued for policies that would produce balanced

growth at a moderate tempo, speaking of growing

into socialism through exchange.

In the mid-1920s Bukharin aligned himself

with the Stalinist majority against the Left, be-

coming a full member of the Politburo in 1924,

and played a major role in the government. He was

the architect of the pro-peasant policies introduced

in 1925 and urged peasants to “enrich yourselves,”

a phrase that would later be used against him. As

editor of Pravda and other party publications, and

a member of the Institute of Red Professors,

Bukharin moved easily in the world of NEP intel-

lectuals and artists and authored government poli-

cies favoring artistic freedom. He became head of

the Comintern in 1926 after the ouster of Grigory

Zinoviev and saw the collapse of his policy of co-

operation with the Chinese Nationalists. In the

same period, Bukharin strongly attacked the Left

Opposition and helped achieve its total ouster from

power in the fall of 1927.

Bukharin supported the 1927 decision of the Fif-

teenth Party Congress to adopt a five-year plan for

Soviet industrialization, but he and the gradualist

policies he advocated fell victim to the radical and vi-

olent way Josef Stalin carried out the plan. Bukharin

opposed Stalin’s harsh measures against the peasants

after the amount of grain marketed fell off sharply.

In September he published “Notes of an Economist,”

criticizing efforts to inflate the industrial goals of the

plan and defending the idea of balanced growth; it is

impossible, he said, “to build today’s factories with

tomorrow’s bricks.” Stalin and his allies counterat-

tacked, labeling Bukharin, Alexei Rykov, and Mikhail

Tomsky the “Right Opposition.” His power already

undercut by the end of 1928, Bukharin was removed

formally from the Politburo, the Comintern, and ed-

itorship of Pravda during 1929 and systematically

vilified. In limbo for the next four years after half-

hearted recantations, horrified by the destruction vis-

ited on the peasantry by collectivization, he served

as research director for the Supreme Economic Coun-

cil and its successor and wrote extensively on cul-

ture and science. In the era of partial moderation

from 1934 to 1936, Bukharin became editor of the

government newspaper, Izvestiya, participated in the

commission to prepare a new Soviet constitution,

and wrote about the danger of fascism in Europe.

BUKHARIN, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH

179

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Communist leader Nikolai Bukharin in London, June 1931.

© H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

The Great Purges ended the domestic truce. Bukharin

was arrested in February 1937. In March 1938, along

with the Right Opposition, he was tried for treason

and counterrevolution in the last great show trial,

the Trial of the Twenty-One, where he was the star

defendant. Bukharin confessed to the charges against

him, probably to save his young wife Anna Larina

and their son Yuri (born 1934), and he was executed

immediately. In the Khrushchev years, Bukharin

came to symbolize an alternative, non-Stalinist path

of development for the Soviet Union. He was reha-

bilitated in 1988, and Larina made public his last

written work, a letter to future party leaders, that

she had preserved by memory during years of im-

prisonment.

See also: LEFT OPPOSITION; LEFT SOCIALIST REVOLUTION-

ARIES; NEW ECONOMIC POLICY; PURGES, THE GREAT;

WAR COMMUNISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bergmann, Theodor; Schaefer, Gert; and Selden, Mark,

eds. (1994). Bukharin in Retrospect. Armonk, NY:

M.E. Sharpe.

Bukharin, Nikolai. (1998). How It All Began. New York:

Columbia University Press.

Cohen, Stephen F. (1973). Bukharin and the Bolshevik Rev-

olution: A Political Biography, 1888–1938. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Haynes, Michael. (1985). Nikolai Bukharin and the Tran-

sition from Capitalism to Socialism. London: Croom

Helm.

Heitman, Sidney. (1969). Nikolai I. Bukharin: A Bibliog-

raphy, with Annotations. Stanford, CA: Hoover In-

stitution.

Kemp-Welch, A., ed. (1992). The Ideas of Nikolai Bukharin.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Larina, Anna (1993). This I Cannot Forget: The Memoirs of

Nikolai Bukharin’s Widow. New York: Norton.

Lewin, Moshe. (1974). Political Undercurrents in Soviet

Economic Debates from Bukharin to the Modern Re-

formers. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Medvedev, Roy A. (1980). Nikolai Bukharin: The Last

Years. New York: Norton.

C

AROL

G

AYLE

W

ILLIAM

M

OSKOFF

BUKOVINA

Bukovina is a region that straddles north-central

Romania and southwestern Ukraine. First records

of the region date back to the fourteenth century,

when the whole territory was a constituent part

of the Moldovan Principality.

From 1504, the region was drawn under indi-

rect Ottoman rule. However, following the Russo-

Turkish war of 1768–1774, the Hapsburg Empire

annexed the region, in accordance with the 1775

Convention of Constantinople.

During the initial stages of Austrian rule,

Bukovina’s population expanded rapidly. The re-

gion’s reputation for religious toleration and re-

laxed feudal obligations saw a wave of German,

Polish, Hungarian, Ukrainian, and Romanian im-

migrants flood into the area.

The collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

in the aftermath of World War I gave rise to a brief

period of dispute concerning rights to the region,

with both Romania and briefly independent

Ukraine claiming sovereignty. The Treaty of Saint

Germain awarded the territory to a newly enlarged

Romania.

Control over the region shifted following the

enactment of the clandestine Ribbentrop-Molotov

pact, as the Soviet Union seized northern Bukov-

ina (to the Sereth River) on June 29, 1940. This

move precipitated an exodus of the region’s Ger-

man settlers.

Germany’s attack on the Soviet Union in 1941

saw the whole territory temporarily revert to Ro-

mania. Bukovina’s sizable Jewish population suf-

fered during this period. However, the region was

retaken by advancing Soviet troops, and in Sep-

tember 1944 northern Bukovina was officially in-

corporated into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist

Republic.

After a period of territorial stability under

Communist rule, focus on the area returned dur-

ing the 1990s. With an estimated 135,000 ethnic

Romanians living in Ukrainian Bukovina, tentative

calls were made by the Romanian government for

a reversion to territorial arrangements that had ex-

isted prior to the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact. The

Ukrainian government’s unwillingness to engage

Romanian demands meant the issue initially

reached a stasis. However, Romania’s application

to join NATO forced a resolution of the dispute and,

as such, a 1997 treaty mutually recognized the ter-

ritorial integrity of the two states.

See also: MOLDOVA AND MOLDOVANS; UKRAINE AND

UKRAINIANS

BUKOVINA

180

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fischer-Galati, Stephen. (1991). Twentieth Century Ruma-

nia. New York: Columbia University Press.

Roper, Steven D. (2000). Romania: The Unfinished Revo-

lution. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers.

J

OHN

G

LEDHILL

BULGAKOV, MIKHAIL AFANASIEVICH

(1891–1940), twentieth-century novelist, journal-

ist, short story writer, and playwright; author of

internationally acclaimed novel Master and Mar-

garita.

Mikhail Afanasievich Bulgakov was born in

Kiev. He graduated from the Kiev University Med-

ical School in 1916 and married Tatiana Lappa, his

first of three wives. He practiced medicine in

provincial villages, then in Kiev, where he witnessed

the outbreak of the Russian Civil War and strug-

gled with morphine addiction. In 1920 he aban-

doned medicine for a writing career and moved to

Vladikavkaz, Caucasus, where he wrote feuilletons

and studied theater.

Bulgakov moved to Moscow in 1921. There

his troubles with censorship began. His satirical

(patently science fiction) novel Heart of a Dog

(Sobache serdtse) was deemed unpublishable. His

play Days of the Turbins (Dni Turbinykh), based on

his autobiographical novel White Guardu (Belaya

Gvardiya), premiered in 1926 and was banned af-

ter its 289th performance (although it supposedly

numbered among Josef Stalin’s favorite plays).

Subsequent plays were banned much earlier in the

production process. His short story “Morphine”

(1927) was his last publication in his lifetime. In

1930 he wrote a long letter (his second) to the So-

viet government requesting permission to emigrate.

He received in response a telephone call from Stalin,

who offered him an assignment as assistant pro-

ducer at the Moscow Art Theater. Although not

subjected to forced labor or confinement, Bulgakov

hardly enjoyed privilege. His work remained un-

published and unperformed. His attempts to ap-

pease the censors by tackling relatively safe subjects

(historical fiction and adaptations) proved futile.

Bulgakov’s novel Master and Margarita was

written between 1928 and 1940. Resonant with the

influence of Nikolai Gogol, it concerns the Devil,

who, disguised as a professor, travels to Moscow

to wreak havoc. This exuberantly irreverent work

swirls with fierce wit, narrative inventiveness, and

a myriad of historical, literary, and religious refer-

ences.

Bulgakov’s last play, Batum (1939), written in

honor of Stalin’s sixtieth jubilee, was banned. Bul-

gakov died of kidney disease in 1940.

See also: GOGOL, NIKOLAI VASILIEVICH; MOSCOW ART

THEATER; THEATER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bulgakov, Mikhail. (1987). Heart of a Dog, reprint ed., tr.

Mirra Ginsburg. New York: Grove.

Bulgakov, Mikhail. (1996). The Master and Margarita,

reprint ed., tr. Diana Burgin and Katherine Tiernan

O’Connor. New York: Vintage.

Milne, Lesley. (1990). Bulgakov: A Critical Biography.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Proffer, Ellendea. (1984). Bulgakov: Life and Work. Ann

Arbor, MI: Ardis.

D

IANA

S

ENECHAL

BULGAKOV, SERGEI NIKOLAYEVICH

(1871–1944), political economist, philosopher, and

theologian, whose life and intellectual evolution

were punctuated by sharp breaks and shifts in

worldview.

Sergei Bulgakov was born into the clerical es-

tate. His father was a rural clergyman in Livny (Orël

province); his mother, of gentry background. Like

Nikolai Chernyshevsky and Nikolai Dobrolyubov a

generation earlier, Bulgakov lost his faith at age

fourteen and transferred from the seminary to the

secular gymnasium at Elets, and then to Moscow

University, where he studied political economy. His

book On Markets in Capitalist Conditions of Produc-

tion (1897) established him, together with Nikolai

Berdyayev, Peter Struve, and Mikhail Tugan-

Baranovsky, as one of Russia’s foremost Legal

Marxists. While researching his doctoral thesis

(“Capitalism in Agriculture”) in Europe, Bulgakov

experienced a spiritual crisis, breaking down in pi-

ous tears before Raphael’s canvas of the Sistine

Madonna in Dresden. Upon his return to Russia, he

spearheaded the movement from Marxism to ideal-

ism (including among others Berdyayev, Semen

Frank, and Struve). Over the next twenty years he

became a key participant in the seminal collections

BULGAKOV, SERGEI NIKOLAYEVICH

181

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

of articles—Problems of Idealism (1902), Landmarks

(1909), From the Depths (1918)—that charted the

collective spiritual evolution of an important seg-

ment of the Russian intelligentsia. Bulgakov’s ide-

alism translated into political involvement in the

Union of Liberation (founded in Switzerland in

1903) and included the drafting of the Cadet (Con-

stitutional Democrat) party’s agrarian program.

During the Revolution of 1905, Bulgakov founded

a small but intellectually sophisticated Christian

Socialist party and was elected to the Second Duma.

Like his fellow liberals and radicals, Bulgakov

experienced severe disappointment following Peter

Stolypin’s June 3 coup, formulated in his article in

Vekhi, criticizing the intelligentsia. But by 1912 he

had regained his sense of direction, finally com-

pleting his doctoral dissertation in a completely

new tone. Philosophy of Economy: The World as

Household (translated into English for the first time

in 2000) is a work of social theory, and fully part

of the “revolt against positivism” (H. Stuart

Hughes) characteristic of European social thought

in the period from 1890 to 1920. The book estab-

lished Bulgakov’s prominence as a thinker of the

Russian Silver Age. In Philosophy of Economy and his

next major work, The Unfading Light (1917), Bul-

gakov became a religious philosopher, bringing the

insights of Orthodox Christianity, and particularly

the concept of Sophia, the Divine Wisdom, to bear

on problems of human dignity and economic ac-

tivity.

Following the February Revolution, Bulgakov

became a delegate to the All-Russian Council of the

Orthodox Church; in 1918 he was ordained as a

priest. Bulgakov was among the two hundred or

so intellectuals Vladimir Lenin ordered shipped out

of the new Soviet Union, across the Black Sea to

Istanbul, in 1922. In his “second life,” first in Prague

and then in Paris, Bulgakov became arguably the

twentieth century’s greatest Orthodox theologian,

crafting two theological trilogies modeled on the

pattern of the liturgy: the “major” (e.g., Agnets

Bozhy) and the “minor.” Bulgakov was founder and

dean of the St. Sergius Theological Academy in Paris

and active in the ecumenical movement, including

the Brotherhood of St. Alban’s and St. Sergius and

the Russian Christian Student Movement. Sophia,

the Divine Wisdom, became a unifying principle in

his writing, even leading to the development of a

doctrine known as Sophiology. A tragic contro-

versy over Sophia erupted in 1935; Bulgakov’s

views were condemned by both the Soviet Ortho-

dox Church and the Synod of the Orthodox Church

in Exile in Czechoslovakia. Bulgakov’s final work

was a commentary on the Apocalypse of St. John

the Divine. In 1944 he died of throat cancer in Paris.

Banned for seventy years in the Soviet Union,

the writings of Bulgakov and his fellow Silver Age

philosophers experienced a resurgence of popular-

ity beginning in 1989.

See also: BERDYAYEV, NIKOLAI ALEXANDROVICH; CON-

STITUTIONAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY; SILVER AGE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Evtuhov, Catherine. (1997). The Cross and the Sickle: Sergei

Bulgakov and the Fate of Russian Religious Philosophy,

1890–1920. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Valliere, Paul. (2000). Modern Russian Theology: Bukharev,

Soloviev, Bulgakov: Orthodox Theology in a New Key.

Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

C

ATHERINE

E

VTUHOV

BULGANIN, NIKOLAI ALEXANDROVICH

(1895–1975), political and military leader.

Nikolai Bulganin was a marshal of the Red

Army who rose to the position of Soviet Prime Min-

ister (1955–1958) under Nikita Khrushchev. Bul-

ganin made his career mainly as a security and

military official, but he was also an urban admin-

istrator. As mayor of Moscow (1931–1937) at a

time when the capital was undergoing rapid ex-

pansion, he collaborated closely with Khrushchev

in the construction of such enduring symbols

of Stalinist urbanization as the Moscow metro.

Bulganin’s career benefited from the purges

(1937–1938). Despite his lack of military training,

Josef Stalin actively promoted him as a party

commissar to oversee the military. He eventually

joined Stalin’s war cabinet in 1944. In 1947 he suc-

ceeded Stalin as minister for the armed forces and

was promoted to marshal. A year later he joined

the Politburo. Shortly after Stalin’s death (1953),

he was appointed minister of defense. In the ensu-

ing political confrontation with secret police chief

Lavrenti Beria, Bulganin sided with his friend

Khrushchev, ensuring the military’s loyalty. Bul-

ganin’s subsequent support for Khrushchev against

Georgy Malenkov, who was advocating reduced

spending on heavy industry, led to Bulganin’s ap-

pointment as prime minister. In this post he ac-

tively supported Khrushchev’s attempts to defuse

BULGANIN, NIKOLAI ALEXANDROVICH

182

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY