Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

kered the collaborations of some of his century’s

most celebrated creative artists, Russian and non-

Russian (Stravinsky, Balanchine, Nijinsky, Pavlova,

and Chaliapin, as well as Debussy, Ravel, Picasso,

and Matisse). A series of art exhibits organized in

Russian in 1897 marked the beginning of Diagilev’s

career as an impresario. Those led to the founding

of an ambitious art journal, Mir iskusstva (The

World of Art, 1898–1904). As Diagilev’s attentions

shifted to Western Europe, the nucleus of Diagilev’s

World of Art group remained with him. His first

European export was an exhibition of Russian

paintings in Paris in 1906. A series of concerts of

Russian music followed the next year, and in 1908

Diagilev brought Russian opera to Paris. With de-

signers Alexandre Benois and Léon Bakst, the

choreographer Michel Fokine, and dancers of such

renown as Vaslav Nijinsky and Anna Pavlova, Di-

agilev began to introduce European audiences to

Russian ballet in 1909.

The early Ballets Russes repertory included

overwrought Orientalist fantasy ballets such as

Schéhérazade (1910), investigations of the antique

(L’Après-midi d’un Faune, 1912), and folkloric rep-

resentations of Russian and Slavic culture (The Fire-

bird, 1910). The company also introduced such

masterworks as Stravinsky’s Petrushka (1911, with

choreography by Fokine) and Rite of Spring (1913,

choreographed by Nijinsky). Whatever the lasting

value of these early collaborations (the original

choreography of many of them has been lost), the

Diagilev ballets were emblematic of Russian Silver

Age culture in their synaesthesia (combining mu-

sic, dance, and décors) and their engagement with

the West.

Diagilev’s company toured Europe and the

Americas for two decades, until the impresario’s

death in 1929. And while many of Diagilev’s orig-

inal, Russian collaborators broke away from his

organization in the years following World War I,

Diagilev’s troupe became a more cosmopolitan en-

terprise and featured the work of a number of im-

portant French painters and composers in those

years. Nonetheless, Diagilev continued to seek out

émigré Soviet artists; the final years of his enter-

prise were crowned by the choreography of George

Balanchine, then an unknown dancer and promis-

ing choreographer.

Diagilev had long suffered from diabetes and

died in Venice in 1929. His influence continued to

be felt in the ballets presented, the companies es-

tablished, and the new popularity of dance in the

twentieth century. The relatively short, one-act

work, typically choreographed to extant symphonic

music, and the new prominence of the male dancer

speak to Diagilev’s influence. An astonishing num-

ber of dance companies established around the

world in the twentieth century owe their existence

to Diagilev’s model; many of them boast a direct

lineage.

See also: BALLET; SILVER AGE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Buckle, Richard. (1979). Diaghilev. New York: Atheneum.

Garafola, Lynn. (1989). Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. New

York: Oxford University Press.

T

IM

S

CHOLL

DIALECTICAL MATERIALISM

A concept in Soviet Marxist-Leninist ideology.

Dialectical materialism was the underlying ap-

proach to the interpretation of history and society

in Soviet Marxist-Leninist ideology. According to

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, in the history of

philosophy, the clash of contradictory ideas has

generated constant movement toward higher lev-

els. Karl Marx poured new content into the dialec-

tic with his materialist interpretation of history,

which asserted that the development of the forces

of production was the source of the conflicts or

contradictions that would demolish each stage of

society and lead to its replacement with a higher

stage. Marx’s collaborator, Friedrich Engels, sys-

tematized the three laws of the dialectic that were

to figure prominently in the official Soviet ideol-

ogy: (a) the transformation of quantity into qual-

ity; (b) the unity of opposites; and (c) the negation

of the negation. According to the first of those

laws, within any stage of development of society,

changes accumulate gradually, until further change

cannot be accommodated within the framework of

that stage and must proceed by a leap of revolu-

tionary transformation, like that from feudal soci-

ety to capitalism. The second law signifies that

within any stage, mutually antagonistic forces are

built into to the character of the system; for in-

stance, the capitalists and the proletariat are locked

in a relationship of struggle, but as long as capi-

talism survives, the existence of each of those

classes presumes the existence of the other. The third

law of the dialectic supposedly reflects the reality

DIALECTICAL MATERIALISM

393

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

that any new stage of society (i.e., capitalism) has

replaced or negated a previous stage, but will itself

eventually be replaced by still another stage of de-

velopment (i.e., communism).

In Soviet Marxist-Leninist ideology under suc-

cessive political leaders, though the insistence on

the universal validity of the laws of the dialectic

became highly dogmatic, the application of those

laws was continually adapted, depending on the

political objectives and calculations of the top lead-

ers. Most crucial is the example of Josef Stalin, who

insisted that the dialectic took the form of destruc-

tive struggle within capitalist societies, but tried to

exempt Soviet socialism from the harshness of such

internal conflict by arguing that in socialism, the

conscious planning and control of change elimi-

nated fundamental inconsistency between the

material base and the political-administrative su-

perstructure. Thus in socialism the interplay of

nonantagonistic contradictions could open the way

to gradual leaps of relatively painless qualitative

transformation. Mikhail Gorbachev later repudi-

ated that reasoning as having been the philosoph-

ical rationale for evading necessary reforms in

political and administrative structures in the Soviet

Union from the 1930s to the 1980s.

See also: HEGEL, GEORG WILHELM FRIEDRICH; LENIN,

VLADIMIR ILICH; MARXISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Avineri, Shlomo. (1971). Karl Marx: Social and Political

Thought. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Carver, Terrell. (1983). Marx and Engels: The Intellectual

Relationship. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Evans, Alfred B., Jr. (1993). Soviet Marxism-Leninism: The

Decline of an Ideology. Westport, CT: Praeger.

A

LFRED

B. E

VANS

J

R

.

DICTATORSHIP OF THE PROLETARIAT

The concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat

originated with Karl Marx and was applied by

Vladimir Lenin as the organizational principle of

the communist state after the Russian Revolution.

Josef Stalin subsequently adopted it to organize

workers’ states in Eastern Europe following the So-

viet takeover after 1945. In China, Mao Zedong

claimed that the communist revolution of 1949

was the first step to establishing a proletarian dic-

tatorship, even though the peasantry had been

largely responsible for the revolution’s success.

In The Communist Manifesto (1848), Marx gave

the reasoning for establishing absolute authority in

the name of the working class: “The first step on

the path to the workers’ revolution is the elevation

of the proletariat to the position of ruling class. The

proletariat will gain from its political domination

by gradually tearing away from the bourgeoisie all

capital, by centralizing all means of production in

the hands of the State, that is to say in the hands

of the proletariat itself organized as the ruling

class.” In Critique of the Gotha Program (1875), he

theorized how “between capitalist and communist

society lies the period of the revolutionary trans-

formation of the one into the other. There corre-

sponds to this also a political transition period in

which the State can be nothing but the revolu-

tionary dictatorship of the proletariat.” Marx em-

ployed the term, then, as absolutist rule not by

an individual but an entire socio-economic class. If

capitalism constituted the dictatorship of the

bourgeoisie, it would be replaced by socialism—a

dictatorship of the proletariat. In turn, socialist dic-

tatorship was to be followed by communism, a

classless, stateless society.

In his 1891 postscript to Marx’s The Civil War

in France (1871), Friedrich Engels addressed social-

democratic critics of this concept: “Well and good,

gentlemen, do you want to know what this dicta-

torship looks like? Look at the Paris Commune.

That was the Dictatorship of the Proletariat.” Dif-

ferences over the principle—and over whether a

conspiratorial communist party was to incorporate

this idea—were to divide the left into revolution-

ary (in Russia, Bolshevik) and reformist (Menshe-

vik) wings.

Lenin developed the praxis of proletarian dicta-

torship in State and Revolution (1917): “The prole-

tariat only needs the state for a certain length of

time. It is not the elimination of the state as a fi-

nal aim that separates us from the anarchists. But

we assert that to attain this end, it is essential to

utilize temporarily against the exploiters the in-

struments, the means, and the procedures of polit-

ical power, in the same way as it is essential, in

order to eliminate the classes, to instigate the tem-

porary dictatorship of the oppressed class.” A dic-

tatorship by and for the proletariat would realize

Lenin’s dictum that the only good revolution was

one that could defend itself. Dictatorship would al-

DICTATORSHIP OF THE PROLETARIAT

394

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

low the working class to consolidate political power,

suppress all opposition, gain control of the means

of production, and destroy the machinery of the

bourgeois state. Political socialization would follow:

“It will be necessary under the dictatorship of the

proletariat to reeducate millions of peasants and

small proprietors, hundreds of thousands of office

employees, officials, and bourgeois intellectuals.”

Paradoxically, Lenin saw this form of dictatorship

as putting an end to “bourgeois-democratic parlia-

mentarism” and replacing it with a system expand-

ing democratic rights and liberties to the exploited

classes.

In sum, for Lenin, “only he is a Marxist who

extends his acknowledgement of the class struggle

to an acknowledgement of the Dictatorship of the

Proletariat.” Moreover, “the dictatorship of the pro-

letariat is a stubborn struggle—bloody and blood-

less, violent and peaceful, military and economic,

educational and administrative—against the forces

and traditions of the old society” (Collected Works,

XXV, p. 190).

In Foundations of Leninism (1924), Stalin iden-

tified three dimensions of the dictatorship of the

proletariat: 1) as the instrument of the proletarian

revolution; 2) as the rule of the proletariat over the

bourgeoisie; and 3) as Soviet power, which repre-

sented its state form. In practice, Lenin, and espe-

cially Stalin, invoked the concept to rationalize the

Communist Party monopoly on power in Russia,

arguing that it alone represented the proletariat.

See also: COMMUNISM; LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH; MARX-

ISM; STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Balibar, Etienne. (1977). On the Dictatorship of the Prole-

tariat. London: NLB.

Draper, Hal. (1987). Dictatorship of the Proletariat from

Marx to Lenin. New York: Harper Review Press.

Ehrenberg, John. (1992). The Dictatorship of the Prole-

tariat: Marxism’s Theory of Socialist Democracy. New

York: Routledge.

R

AY

T

ARAS

DIOCESE

In early Greek sources (eleventh and twelfth cen-

turies), the term signified a province, either secu-

lar or ecclesiastical. In Rus’, and later in Russia, the

term was used only in the ecclesiastical sense to

mean the area under the jurisdiction of a prelate.

Church organization evolved along with the

spread of Christianity. The metropolitan of Kiev

headed the Church in Rus’. Bishops and dioceses

soon were instituted in other principalities. Fifteen

dioceses were created in the pre-Mongol period.

Compared with their small, compact Greek models

centered on cities, these dioceses were vast in ex-

tent with vague boundaries and thinly populated,

like the Rus’ land itself.

The Mongol invasions changed the course of

political and ecclesiastical development. The politi-

cal center shifted north, ultimately finding a home

in Moscow. Kiev and principalities to the southwest

were lost, although claims to them were never re-

linquished. Church organization adapted to these

changes. In the initial onslaught, several dioceses

were devastated and many remained vacant for

long periods. Later new dioceses were created, in-

cluding the diocese of Sarai established at the Golden

Horde. By 1488 when the growing division in the

church organization solidified with one metropol-

itan in Moscow and another in Kiev, there were

eighteen dioceses. Nine dioceses (not including the

metropolitan’s see) were subordinated to Moscow;

nine dioceses looked to the metropolitan seated in

Kiev.

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries wit-

nessed the elevation of the metropolitan of Moscow

to patriarch (1589), periods of reform directed at

strengthening church organization and raising the

spiritual level of parishioners, and the subordina-

tion of the see of Kiev with its suffragens to the

Moscow patriarch (1686). Ecclesiastical structure

responded to these profound changes. By 1700 the

number of dioceses had increased to twenty-one

(excluding the Patriarchal see) as the Church strug-

gled to create an effective organization able to meet

the spiritual needs of the people and suppress dis-

sident voices that had emerged. Thirteen of these

dioceses were headed by metropolitans, seven by

archbishops, and one by a bishop.

In 1721 the patriarchate was abolished and re-

placed by the Holy Synod. Despite this momentous

change in ecclesiastical organization, the long-term

trend of increasing the number of dioceses contin-

ued. In 1800 there were thirty-six dioceses; by

1917 the number had grown to sixty-eight. More

and smaller dioceses responded to increased and

changing responsibilities, particularly in the areas

of education, charity, and missionary activity, but

DIOCESE

395

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

also in the area of social control and surveillance

as servants of the state.

The Bolshevik Revolution destroyed the orga-

nization of the Russian Church, making prisoners,

fugitives, exiles, and martyrs of its prelates. The

catastrophes that characterized the beginning of

World War II prompted Stalin to initiate a partial

rapprochement with the Church. This permitted a

revival of its organization, but under debilitating

constraints. In the 1990s, following the collapse of

the Soviet Union, the Russian Orthodox Church en-

tered a new period institutionally. Constraints were

lifted, the dioceses revived and liberated. By 2003

there were 128 functioning dioceses.

See also: RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cracraft, James. (1971). The Church Reform of Peter the

Great. London and Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan and

Co. Ltd.

Fennell, John. (1995). A History of the Russian Church to

1448. London and New York: Longman.

Muller, Alexander V., trans. and ed. (1972). The Spiritual

Regulation of Peter the Great. Seattle: University of

Washington Press.

Popielovsky, Dmitry. (1984). The Russian Church under

the Soviet Regime 1917–1982. Crestwood, NY: St.

Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Russian Orthodox Church. <http://www.russian-

orthodox-church.org.ru/en.htm>

C

ATHY

J. P

OTTER

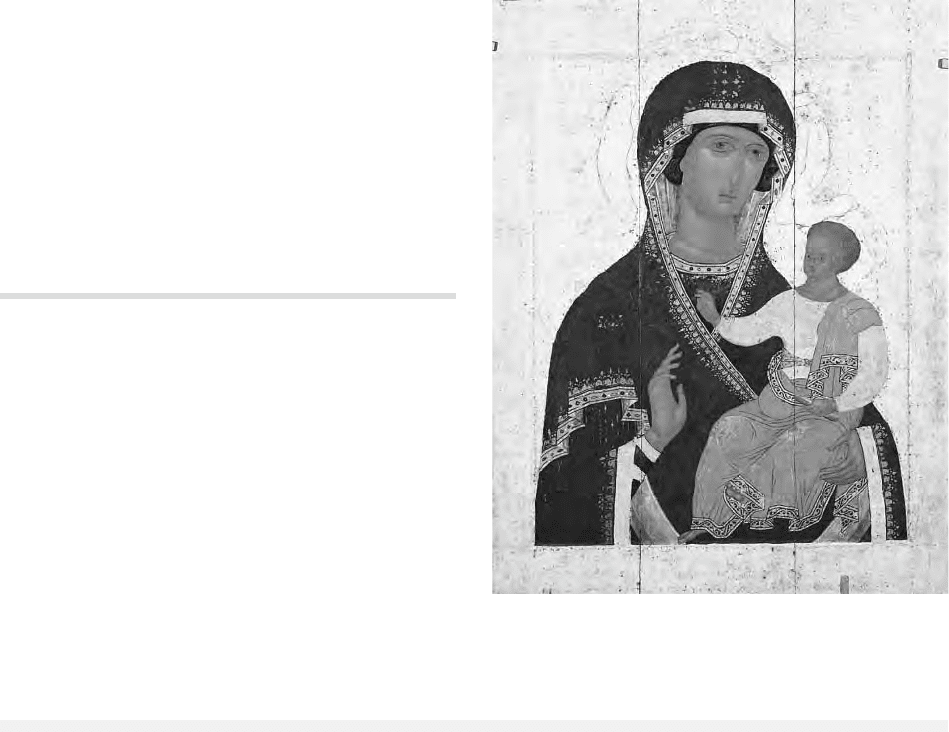

DIONISY

(c. 1440–1508), renowned Russian painter.

Dionisy was the first Russian layman known

to have been a religious painter and to have run a

large, professional workshop. He was associated

with the Moscow School and is considered the most

outstanding icon painter of the later fifteenth cen-

tury in Russia. His biographer, Joseph of Volotsk

(1440–1515), called him “the best and most cre-

ative artist of all Russian lands.” Certainly this can

be considered true for his time period.

Dionisy’s first recorded works were frescoes in

the Church of St. Parfuntiev in the Borovsky

Monastery, completed around 1470 when he was

an assistant to the painter Mitrophanes. In 1481

the Archbishop Vassian of Rostov, a close friend of

the Great Prince of Moscow Ivan III, asked Dionisy

to paint icons for the iconostasis of the Cathedral

of the Dormition, Russia’s main shrine in the

Moscow Kremlin. This cathedral had just been fin-

ished by Aristotle Fioravanti, a well-known archi-

tect and engineer from Bologna, Italy. In this task

Dionisy was assisted by three coworkers: Pope

Timothy, Yarete, and Kon. Some fragmentary fres-

coes in this cathedral are also attributed to Dion-

isy, painted prior to the icon commission.

In 1484 Paisi the Elder and Dionisy, with his

sons Fyodor and Vladimir, painted icons for the

Monastery of Volokolamsk. It is generally agreed

that the greatest achievement of Dionisy is the

group of frescoes in the Church of the Nativity of

the Virgin at St. Ferapont Monastery on the White

Lake. He signed and dated this work 1500–1502.

He was assisted again by his two sons. The entire

fresco program centers on the glorification of the

DIONISY

396

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The Theotokos

by Dionisy. © R

USSIAN

S

TATE

M

USEUM

, S

T

.

P

ETERSBURG

, R

USSIA

/L

EONID

B

OGDANOV

/S

UPER

S

TOCK

Virgin Mary. However, the usual Pantocrator

(Christ enthroned, “Ruler of All”) appears in the

dome, but without the severity of earlier represen-

tations. In the apse the enthroned Virgin and Child

are represented above the Liturgy of the Church Fa-

thers. The nave walls have frescoes illustrating

scenes from the Akathist Hymn praising the Vir-

gin. Some unusual scenes of the life and miracles

of Christ also appear (Parables of the Prodigal Son,

Widow’s Mite, and so forth). Dionisy apparently

invented some compositions instead of copying tra-

ditional representations.

Stylistically he was very much indebted to the

venerated Andrei Rublev who died in 1430. Char-

acteristic of Dionisy’s style is the “de-materialized

bouyancy” (Hamilton) of his figures, which appear

to be extremely attenuated. In addition, his figures

have a certain transparency and delicacy that are

distinctive to his approach.

Icon panels attributed to Dionisy include a large

icon of St. Peter, the Moscow Metropolitan, St.

Alexius, another Moscow Metropolitan, St. Cyril of

Byelo-Ozersk, a Crucifixion icon, a Hodegetria icon,

and an icon glorifying the Virgin Mary entitled “All

Creation Rejoices in Thee.” The Crucifixion icon es-

pecially characterizes his style. Christ’s rhythmi-

cal, languid body with tiny head (proportions 1:12)

dominates the composition while his followers, on

a smaller scale, levitate below. A curious addition—

perhaps from western influence—are the depictions

of the floating personified Church and Synagogue,

each accompanied by an angel.

The influence of Dionisy is clearly evident in

subsequent sixteenth-century Russian icons and

frescoes as well as in manuscript illuminations.

See also: CATHEDRAL OF THE DORMITION; RUBLEV, AN-

DREI; THEOPHANES THE GREEK

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hamilton, George H. (1990). The Art and Architecture of

Russia. London: Penguin Group.

Lazarev, Viktor. (1966). Old Russian Murals and Mosaics:

From the Eleventh to the Sixteenth Century. London:

Phaidon.

Simonov, Aleksandr Grigorevich. (1970). The Frescoes of

St. Pherapont Monastery. Moscow: Iskusstvo Pub-

lishing House.

A. D

EAN

M

C

K

ENZIE

DISENFRANCHIZED PERSONS

Soviet Russia’s first Constitution of 1918 decreed

that the bourgeois classes should be disenfran-

chised. The categories of people marked for disen-

franchisement included those who hire labor for

the purpose of profit; those who live off unearned

income such as interest money or income from

property; private traders and middlemen; monks

and other clerics of all faiths and denominations;

agents of the former tsarist police, gendarmes,

prison organs, and security forces; former noble-

men; White Army officers; leaders of counterrev-

olutionary bands; the mentally ill or insane; and

persons sentenced by a court for crimes of profit

or depravity. However, many more people were

vulnerable to the loss of rights. Vladimir Lenin de-

clared that his party would “disenfranchise all cit-

izens who hinder socialist revolution.” In addition,

family members of disenfranchised persons shared

the fate of their relatives “in those cases where they

are materially dependent on the disenfranchised

persons.”

Also described as lishentsy, the disenfranchised

were not only denied the ability to vote and to be

elected to the local governing bodies or soviets: Un-

der Josef Stalin the disenfranchised lost myriad

rights and became effective outcasts of the Soviet

state. They lost the right to work in state institu-

tions or factories or to serve in the Red Army. They

could not obtain a ration card or passport. The dis-

enfranchised could not join a trade union or adopt

a child, and they were denied all forms of public

assistance, such as a state pension, aid, social in-

surance, medical care, and housing. Many lishentsy

were deported to forced labor camps in the far north

and Siberia.

In 1926, the government formalized a proce-

dure that made it possible for some of the disen-

franchised to be reinstated their rights. Officially,

disenfranchised persons could have their rights re-

stored if they engaged in socially useful labor and

demonstrated loyalty to Soviet power. Hundreds of

thousands of people flooded Soviet institutions

with various appeals for rehabilitation, and some

managed to reenter the society that excluded them.

According to statistics maintained by the local

soviets, over 2 million people lost their rights, but

these figures on the number of people disenfran-

chised are probably underestimated. In the electoral

campaigns of 1926 to 1927 and 1928 to 1929, the

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR)

DISENFRANCHIZED PERSONS

397

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

reported roughly 3 to 4 percent of rural and 7 to

8 percent of the urban residents disenfranchised as

a percentage of the voting-age population. Rates of

disenfranchisement were higher in those areas with

large non-Russian populations. Although por-

trayed as bourgeois elements, the disenfranchised

actually included a wide variety of people, such as

gamblers, tax evaders, embezzlers, and ethnic mi-

norities. The poor, the weak, and the elderly were

especially vulnerable to disenfranchisement.

Disenfranchisement ended with Stalin’s 1936

Constitution, which extended voting rights to all

of the former categories of disenfranchised people

except for the mentally ill and those sentenced by

a court to deprivation of rights. Nonetheless, “for-

mer people,” or those with ties to the old regime,

remained vulnerable during subsequent campaigns

of Stalinist terror.

See also: BOLSHEVISM; CONSTITUTION OF 1918; CONSTI-

TUTION OF 1936; LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexopoulos, Golfo. (2003). Stalin’s Outcasts: Aliens, Cit-

izens, and the Soviet State, 1926–36. Ithaca, NY: Cor-

nell University Press.

Fitzpatrick, Sheila. (1993). “Ascribing Class: The Con-

struction of Social Identity in Soviet Russia.” Jour-

nal of Modern History 65:745–770.

Kimberling, Elise. (1982). “Civil Rights and Social Policy

in Soviet Russia, 1918–36.” Russian Review 41:24–46.

G

OLFO

A

LEXOPOULOS

DISHONOR See BECHESTIE.

DISSIDENT MOVEMENT

Individuals and informal groups opposed to Com-

munist Party rule.

This movement comprised an informal, loosely

organized conglomeration of individual and group-

based dissidents in the decades following the death

of Josef Stalin in March 1953 through the end of

the Cold War in the late 1980s. They opposed their

posttotalitarian regimes, accepting, as punishment,

exile, imprisonment, and sometimes even death. The

dissidents subjected their fellow citizens to moral

triage. By the year 1991, they helped to bring down

the regimes in Europe, which, for a number of rea-

sons, had already embarked upon a political mod-

ernization and democratization process. Dissidents

were less successful in the East and Southeast Asian

countries of the communist bloc. It may be ironic

that with the reversion to authoritarian practices in

such former Soviet republics as the Russian Feder-

ation, Belarus, and the Ukraine by the turn of the

twenty-first century, dissidents have reappeared in

the 2000s as individuals, or, at most, small groups,

but not as a movement.

DEFINITIONS

The most precise historical usage dates from the late

1960s. The term “dissident” (in Russian, inakomys-

liachii for men or inakomysliachaia for women) was

first applied to intellectuals opposing the regime in

the Soviet Union. Then, in the late 1970s, it spread

to Soviet-dominated East Central and Southeast Eu-

rope, which was also known as Eastern Europe.

Most broadly, a dissident may be defined as an out-

spoken political and social noncomformist.

The classic definition of dissent in the East Cen-

tral European context is that by Vaclav Havel, a lead-

ing dissident himself and later president of the

Czechoslovak and Czech Republics, from December

1989 until his resignation February 2, 2003. Wrote

Havel: “[Dissent] is a natural and inevitable conse-

quence of the present historical phase of the [Com-

munist dictatorship—Y.B.] system it is haunting. It

was born at a time, when this system, for a thou-

sand reasons, can no longer base itself on the unadul-

terated, brutal, and arbitrary application of power,

eliminating all expressions of nonconformity. What

is more, the system has become so ossified politi-

cally that there is practically no way for such non-

conformity to be implemented within its official

structures” (Havel, 1985, p. 23). Havel thus places

dissent into the post-Stalinist or posttotalitarian

phase of the communist system. The semi-ironic

concept of dissent also implies that its practitioners,

the dissidents, differed in their thinking from the ma-

jority of their fellow citizens and were thus doomed

to failure. By making, however, common cause with

the party reformers in the governing structures, the

dissidents, including Havel, prevailed for good in

Eastern Europe, and at least temporarily in the Rus-

sian Federation, Belarus, and the Ukraine.

SOVIET LEADERS AND

LEADING DISSIDENTS

The party reformer Nikita Khrushchev, who after

Stalin’s death headed the Soviet regime from March

DISHONOR

398

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

1953 to October 1964, was committed to building

communism in the Soviet Union, in Soviet-domi-

nated Eastern Europe and throughout the world.

Paradoxically, he ended by laying the political and

legal foundations for the dissident movement. That

movement flourished under Khrushchev’s long-

term successor Leonid Brezhnev (October 1964–No-

vember 1982). Being more conservative, Brezhnev

wanted to restore Stalinism, but failed, partly be-

cause of the opposition from dissidents. After the

brief tenure of two interim leaders—the tough re-

former Yuri Andropov (November 1982–February

1984) and the conservative Konstantin Chernenko

(February 1984–March 1985)—power was assumed

by Andropov’s young protégé, the ambitious mod-

ernizer Mikhail Gorbachev (March 1985–December

1991). Like Khrushchev, Gorbachev both fought

and encouraged the dissident movement. Ulti-

mately, he failed all around. By December 1991,

the Soviet Union withdrew from its outer empire

in Eastern Europe and saw the collapse of its inner

empire. It ceased to exist, and Gorbachev resigned

from the presidency December 25, 1991.

The most outstanding ideological leaders of the

Soviet dissidents were, from the Left to the Right,

Roy Medvedev (Medvedev, 1971), Peter Grigorenko

(Grigorenko, 1982), Andrei Sakharov (Sakharov,

1968, 1992), and Alexander Solzhenitsyn (Solzhen-

itsyn: 1963, 1974–1978). The more radical Andrei

Amalrik (Amalrik, 1970) cannot be easily classi-

fied: he dared to forecast the breakup of the Soviet

Union, but he also wrote one of the first critical

analyses of the movement. Very noteworthy are

Edward Kuznetsov (Kuznetsov, 1975), a represen-

tative of the Zionist dissent; Yuri Orlov (Alex-

eyeva, 1985), the political master strategist of the

Helsinki Watch Committees; and Tatyana Ma-

monova (Mamonova, 1984), the leader of Russian

feminists.

A Marxist socialist historian leaning toward

democracy, Medvedev helped Khrushchev in his

attempt to denounce Stalin personally for killing

Communist Party members in the 1930s (Medvedev,

1971). Medvedev also provided intellectual under-

pinning for Khrushchev’s drawing of sharp dis-

tinctions between a benevolent Vladimir Lenin and

a psychopathic Stalin, between a fundamentally

sound Leninist party rank-and-file and the ex-

cesses of the Stalinists in the secret police and in

the party apparatus. This was better politics than

history. Major General Peter Grigorenko, who was

of Ukrainian peasant origin, shared with Roy

Medvedev the initial conviction that Stalin had de-

viated from true Leninism and with Roy’s brother

Zhores Medvedev, who had protested against the

regime’s mistreatment of fellow biologists, the

wrongful treatment in Soviet asylums and foreign

exile. As a dissident, Grigorenko was more straight-

forward. As early as 1961, he began to criticize

Khrushchev’s authoritarian tendencies, and under

Brezhnev he became a public advocate of the Crimean

Tatars’ return to the Crimea. He also joined the elite

Sakharov–Yelena Bonner circle within the Helsinki

Watch Committees movement, having been a char-

ter member of both the Moscow Group since May

1976 and the Ukrainian Group since November

1976 (Reich, 1979; Grigorenko, 1982). Through his

double advocacy of the Crimean Tatars and his fel-

low Ukrainians, Grigorenko helped to sensitize the

liberal Russian leaders in the dissident movement

to the importance of a correct nationality policy

and also of the restructuring of the Soviet federa-

tion.

Academician Sakharov, a nuclear physicist, the

“father of the Soviet hydrogen bomb,” and an eth-

nic Russian, was one of the foremost moral and in-

tellectual leaders of the Soviet dissident movement,

the other being his antipode, the writer and ethnic

Russian Solzhenitsyn. Unlike the Slavophile and

Russian conservative Solzhenitsyn, who had ex-

pressed nostalgia for the authoritarian Russian past

and had been critical of the West, Sakharov be-

longed to the liberal Westernizing tradition in Russ-

ian history and wanted to transform the Soviet

Union in accordance with liberal Western ideas

(Sakharov 1974, Solzhenitsyn 1974). As a politi-

cal leader of the dissident movement, Sakharov

practiced what he preached, especially after mar-

rying the Armenian-Jewish physician Bonner,

whose family had been victimized by the regime.

He became active in individual human rights cases

or acts of conscience, and thus set examples of civic

courage. So long as the dissenter observed nonvio-

lence, Sakharov publicly defended persecuted fellow

scientists; Russian poets and politicians; and

Crimean Tatars, who wanted to return to their

homeland in the Crimea. He even spoke up for per-

secuted Ukrainian nationalist Valentyn Moroz,

whose politics was more rightist than liberal. In

1970, Sakharov had also defended the former Rus-

sian-Jewish dissident turned alienated Zionist

Kuznetsov, who was initially sentenced to death for

attempting to hijack a Soviet plane to emigrate to

Israel. To his death in December 1989, Sakharov

remained the liberal conscience of Russia.

DISSIDENT MOVEMENT

399

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

DISSIDENT GROUPS, THEIR ACTIONS,

AND SOVIET COUNTERACTIONS

As to the different groups and newsletters in the

Soviet movement, David Kowalewski has counted

and categorized as many as forty-three, of which

six were religious. Of the thirty-seven secular

groups, eleven were general, or multipurpose de-

fenders of rights, nine were ethnic with all-Union

membership or aims, seven were political, three

each were socialeconomic and social, and one each

was economic, artistic, intellectual, and cultural-

religious. The inclusion of more regionally based

and oriented groups from the Baltic States, Trans-

caucasia, and the Ukraine would increase the num-

ber of ethnic groups by at least four. According to

first secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine

Volodymyr V. Sherbytsky, on May 16, 1989, there

were about fifteen anti-Socialist groupings in

Ukraine.

What did the Soviet dissidents actually do?

How did the regime react? What did the dissidents

accomplish? Almost two thousand dissidents

openly signed various appeals before 1968 (Ruben-

stein 1985, p. 125) Over time, hundreds took part

in public demonstrations during Soviet Constitu-

tion Day (December 10), and on special occasions,

such as the protest of seven against the USSR-led

Warsaw Pact forces marching into Czechoslovakia

in August 1968. Poets and writers surreptitiously

published their works, which like much of nine-

teenth-century Russian literature carried a political

and social message, in the post-Stalinist Soviet

Union (the so-called samizdat, or self-publishing),

or even abroad (tamizdat in Russian, meaning lit-

erally “published there”). Some of the poems would

also be read publicly, in a political demonstration.

The documentarists among the dissidents meticu-

lously recorded facts, especially in The Chronicle of

Current Events. They worked hand in glove with the

legalists, who insisted that the regime observe its

own laws and the explicit norms of the Stalin Con-

stitution of 1936. In October 1977, Brezhnev had

a more factual constitution passed, but it was too

late to defeat the legalists. Hundreds of thousands

of Soviet Jews insisted on their right to leave the

country altogether, and so did tens of thousands

of Soviet Germans. Baltic dissidents protested both

the current discriminatory policies of the regime

and their countries having been forcibly included

in the Soviet Union after the Molotov-Ribbentrop

Pact of August 1939. Ukrainian dissidents insisted

that the linguistic Russification was unconstitu-

tional and that the regime’s policies in economics

foreshadowed the abolition of Soviet republics and

the merger of the Ukrainian people with the eth-

nic Russians. The movement was partly self-fi-

nanced in that professionals donated their services

free and the more successful authors of tamizdat

such as Solzhenitsyn remitted their earnings to fel-

low dissidents in the USSR, especially to those that

were imprisoned by the regime. Some of the funds

were channeled from abroad: They were donations

either by private foreign citizens, or by foreign gov-

ernments.

By a stroke of political genius, in 1976 ethnic

Russian Orlov brought the disparate sections of the

dissident movement together in the Helsinki Watch

Committees. Brezhnev wanted to legitimize his

hold over Eastern Europe in the Helsinki accords,

and the United States, Canada, and Western Ger-

many insisted on the inclusion of human rights

provisions. Taking a leaf from the legalists, Orlov,

Bonner, and Sakharov insisted that the regime

should be publicly aided in observing its new com-

mitments toward its own citizens. Moreover, Orlov

persuaded sympathetic American congresspersons

and senators, such as the late Mrs. Millicent Fen-

wick, that with the support of the U.S. govern-

ment, the Helsinki Review Process would work. It

would advance the global cause of human rights

and, on a regional level, would help Yuri Orlov’s

fellow Soviet citizens and also benefit Mrs. Fen-

wick’s political constituents, who wanted their rel-

atives to be allowed to emigrate to the West and to

Israel.

What was the reaction of the Soviet govern-

ment? At the very least, Brezhnev and his security

chief and eventual successor Andropov ordered the

disruption of public demonstrations by the dissi-

dents by hiring a brass band or having thugs beat

them up. The names of all the petitioners would be

recorded and the more persistent letter signers

would be talked to by the secret police, stripped of

privileges such as foreign travel, and eventually dis-

missed from their jobs. The next step could be ex-

ile from Moscow, such as that of Sakharov from

January 1880 to December 1986. Others, as for in-

stance the famous tamizdat authors Andrei

Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel, would be formally

tried, sentenced to long terms in prison camps, and

expelled abroad after serving their sentences. The

show trials led to further protests by dissidents and

criticisms in the West. Brezhnev and Andropov

tightened the screw by placing professionals with

an intellectual bent in asylums, where they were

DISSIDENT MOVEMENT

400

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

given mind-altering drugs, and also by authoriz-

ing the killing, whether by medical neglect during

incarceration or by hired thugs, of carefully cho-

sen dissidents. The most frightening aspect of the

regime’s policy was that the individual dissident did

not know what fate had been decided for him or

her. The post-Stalinist system of power was not

fully posttotalitarian in that it retained Stalin’s op-

tion of unpredictability.

THE MOVEMENT’S SUCCESS

OR FAILURE

From the perspective of the first years of the

twenty-first century, it is not clear whether Gor-

bachev would have embarked upon reforms and

modernization by himself in the expectation that

he would be given massive economic aid from the

United States and Western Europe, or whether the

pro-Western dissidents helped tilt his approach.

The Soviet mode of economic and political think-

ing has been overcome in such East Central Euro-

pean countries as Poland, where after repeated

political insurrections in 1956, 1968, 1970, and

1976 the dissidents coalesced in Solidarity in the

1980s (Rupnik 1979, Walesa 1992) in Hungary

with its revolution of October 1956 in the Czech

and Slovak republics that had benefited from

Havel’s moral leadership and in all three Baltic

states where the dissidents have won political ma-

jorities. In the old Soviet Union, within the bound-

aries of September 1, 1939 (that is, with the

probable exception of the Western Ukraine), Soviet

attitudes have come back: wholesale in Belarus,

where the dissident movement had been weak, and

partly in Russia and Ukraine, where the dissidents

continue operating as a tolerated political minor-

ity within “hybrid” (partly democratic, partly au-

thoritarian) regimes.

In the old Soviet Union, where the citizens had

lived under the communist regime for seventy

years—as opposed to forty years in East Central

Europe—many persons were like walking wounded.

The dissident movement submitted their fellow cit-

izens to a moral triage between members of the dis-

sidents and members of the establishment, between

the dissidents’ foul- and fair-weather friends, be-

tween the establishment’s decent reformers and its

willing executioners. The dissident movement also

raised fundamental questions about the future of

Russia. Solzhenitsyn wondered whether Russia

should return to a humane conservative monar-

chy, while Sakharov, with the support of U.S. pres-

idents and West European statesmen, chose to

work for a liberal democracy and a civic society.

Most interesting in view of the resurgence of pro-

Soviet thinking in Russia and the Eastern Ukraine

in the twenty-first century is the harsh judgment

of the Zionist wouldbe emigrant Kuznetsov, who

challenged both Solzhenitsyn and Sakharov. Wrote

Kuznetsov December 14, 1970: “The essential char-

acteristics of the structure of the regime are to all

intents and purposes immutable, and . . . the par-

ticular political culture of the Russian people may

be classed as despotic. There are not many varia-

tions in this type of power structure, the frame-

work of which was erected by Ivan the Terrible and

by Peter the Great. I think that the Soviet regime is

the lawful heir of these widely differing Russian

rulers. . . . It fully answers the heartfelt wishes of

a significant—but alas not the better—part of its

population” (Kuznetsov, 1975, p. 63; Rubenstein,

1985, pp. 170–171). Was the dissident movement,

therefore, bound to fail in the old Soviet Union?

The definitive answer may be given later, a gener-

ation after the breakup of the USSR, or roughly by

the year 2021.

See also: BREZHNEV, LEONID ILICH; GRIGORENKO, PETER

GRIGORIEVICH; INTELLIGENTSIA; KHRUSHCHEV, NIKITA

SERGEYEVICH; MEDVEDEV, ROY ALEXANDROVICH; NA-

TIONALISM IN THE SOVIET UNION; SAKHAROV, ANDREI

DMITRIEVICH; SAMIZDAT; SOLZHENITSYN, ALEXAN-

DER ISAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexeyeva, Ludmilla. (1985). Soviet Dissent, tr. John Glad

and Carol Pearce. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan Uni-

versity Press.

Amalrik, Andrei A. (1970). Will the Soviet Union Survive

until 1984? New York: Harper and Row.

Brumberg, Abraham, ed. (1968). “In Quest of Justice:

Protest and Dissent in the USSR.” Parts I and II, Prob-

lems of Communism 17(4 and 5):1–119, 1–120.

Grigorenko, Petro. (1982). Memoirs, tr. Thomas P. Whit-

ney. New York: Norton.

Havel, Vaclav. (1985). “The Power of the Powerless.” In

Havel, Vaclav, et al., The Power of the Powerless: Cit-

izens Against the State in Central-Eastern Europe, ed.

John Keane. London: Hutchinson.

Kowalewski, David. (1987). “The Union of Soviet So-

cialist Republics.” In International Handbook of Human

Rights, ed. Jack Donnelly and Rhoda E. Howard.

Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

DISSIDENT MOVEMENT

401

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Kuznetsov, Edward. (1975). Prison Diaries, tr. Howard

Spier. New York: Stein and Day.

Mamonova, Tatyana, ed. (1984). Women and Russia.

Boston: Beacon Press.

Medvedev, Roy A. (1971). Let History Judge, tr. Collen

Taylor, ed. David Joravsky and Georges Haupt. New

York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Putin, Vladimir. (2000). First Person: An Astonishingly

Frank Self-Portrait by Russia’s President Vladimir

Putin, with Nataliya Gevorkyan, Natalya Timakova,

and Andrei Koslesnikov, tr. Catherine A. Fitzpatrick.

New York: Public Affairs.

Reddaway, Peter, and Bloch, Sidney. (1977). Psychiatric

Terror. New York: Basic Books.

Reich, Walter. (1979). “Grigorenko Gets a Second Opin-

ion” The New York Times Magazine, May 13, 1979:

18, 39–42, 44, 46.

Rubenstein, Joshua. (1985). Soviet Dissidents: Their Strug-

gle for Human Rights, 2nd edition, revised and ex-

panded. Boston: Beacon Press.

Sakharov, Andrei A. (1968). Progress, Coexistence and In-

tellectual Freedom, tr. The New York Times. New York:

Norton.

Sakharov, Andrei A. (1974). “In Answer to Solzhenitsyn

[Letter to the Soviet Leaders],” dated April 3, 1974,

trans. Guy Daniels. New York Review of Books 21(10)

June 13, 1974:3–4,6.

Sakharov, Andrei A. (1992). Memoirs, tr. Richard Lourie.

New York: Vintage Books.

Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr I. (1963). One Day in the Life of

Ivan Denisovich, tr. Max Hayward and Ronald Hin-

gley. New York: Praeger.

Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr I. (1974). Letter to the Soviet

Leaders, trans. Hilary Sternberg. New York: Index on

Censorship in association with Harper and Row.

Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr I. (1985). The Gulag Archipelago

1918–1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation,

tr. Thomas P. Whitney (Parts I–IV) and Harry Wil-

letts (Parts V–VII), abridged by Edward E. Ericson,

Jr. New York: Harper and Row.

Taagepera, Rein. (1984). Softening Without Liberalization

in the Soviet Union: The Case of Juri Kukk. Lanham,

MD: University Press of America.

Verba, Lesya, and Yasen, Bohdan, eds. (1980). The Hu-

man Rights Movement in Ukraine: Documents of the

Ukrainian Helsinki Group 1976–1980. Baltimore:

Smoloskyp Publishers.

Walesa, Lech. (1992). The Struggle and the Triumph: An

Autobiography, with the collaboration of Arkadius

Rybicki, tr. Franklin Philip, in collaboration with He-

len Mahut. New York: Arcade Publishers.

Y

AROSLAV

B

ILINSKY

DMITRY ALEXANDROVICH

(d. 1294), Grand prince of Vladimir.

In 1260 Dmitry Alexandrovich was appointed

to Novgorod by his father Alexander Yaroslavich

“Nevsky” who, two years later, ordered him to at-

tack the Teutonic Knights at Yurev (Tartu, Dorpat)

in Estonia. But in 1264, after his father died, the

Novgorodians evicted Dmitry because of his youth.

Nevertheless, in 1268 they requested him to wage

war against the castle of Rakovor (Rakvere, We-

senburg) in Estonia. After Dmitry’s uncle Yaroslav

of Vladimir died in 1271, he occupied Novgorod

again, but his uncle Vasily evicted him. Vasily died

in 1276, and Dmitry replaced him as grand prince

of Vladimir. After that the Novgorodians once

again invited him to rule their town. While there

he waged war on Karelia and in 1280 built a stone

fortress at Kopore near the Gulf of Finland. In 1281,

however, Dmitry quarreled with the Novgorodi-

ans. He waged war against them and because of

this failed to present himself to the new Khan in

Saray. His younger brother Andrei, who did visit

the Golden Horde, was therefore awarded the patent

for Vladimir. Because Dmitry refused to abdicate,

the khan gave Andrei troops with which he evicted

his brother and seized Vladimir and Novgorod.

Dmitry fled to Sweden and later returned to

Pereyaslavl. In 1283, when Andrei brought Tatar

troops against him, Dmitry sought help from Khan

Nogay, an enemy of the Golden Horde, who gave

him troops. They wreaked havoc on northern Rus-

sia. Andrei eventually capitulated but continued to

plot Dmitry’s overthrow. In 1293, after summon-

ing the Tatars the fourth time, he succeeded in forc-

ing Dmitry’s abdication. Dmitry died in 1294 while

returning to Pereyaslavl Zalessky.

See also: ALEXANDER YAROSLAVICH; ANDREI ALEXAN-

DROVICH; GOLDEN HORDE; NOVGOROD THE GREAT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fennell, John. (1983). The Crisis of Medieval Russia

1200–1304. London: Longman.

Martin, Janet. (1995). Medieval Russia 980–1584. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

DMITRY ALEXANDROVICH

402

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY