Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ian-speaking industrial cadres as a result of his eth-

nocratic policies. In mid-1993, Dudayev disbanded

the opposition-minded Constitutional Court and

dispersed the parliament (an example that he then

advised Yeltsin to follow). From then on, he was

faced with armed rebels, aided by Moscow hard-

liners. Initially a secular ruler, by late 1994 he

shifted to Islamist rhetoric. In December 1994, af-

ter failed negotiations and a botched attempt by

pro-Moscow rebels to dislodge him, Chechnya was

invaded by federal troops. Dudayev had to flee

Grozny and thereafter led the armed resistance in

the mountains, up until his death in a rocket at-

tack by federal forces in April 1996.

See also: CHECHNYA AND CHECHENS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dunlop, John B. (1998). Russia Confronts Chechnya: Roots

of a Separatist Conflict. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Lieven, Anatol. (1998). Chechnya: Tombstone of Russian

Power. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

D

MITRI

G

LINSKI

DUGIN, ALEXANDER GELEVICH

(b. 1962), head of the Russian sociopolitical move-

ment Eurasia; editor of the journal Elementy; and a

leading proponent of geopolitics and Eurasianism

with a strong Anti-Western, anti-Atlantic bias.

In the late 1970s Dugin entered the Moscow

Aviation Institute but was expelled during his sec-

ond year for what he described as “intensive activ-

ities.” He joined the circles associated with a Russian

nationalist movement of the 1980s and at the end

of the 1980s was a member of the Central Coun-

cil of the national-patriotic front “Pamyat” (Mem-

ory), then led by Dmitry Vasiliev. With the end of

DUGIN, ALEXANDER GELEVICH

413

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

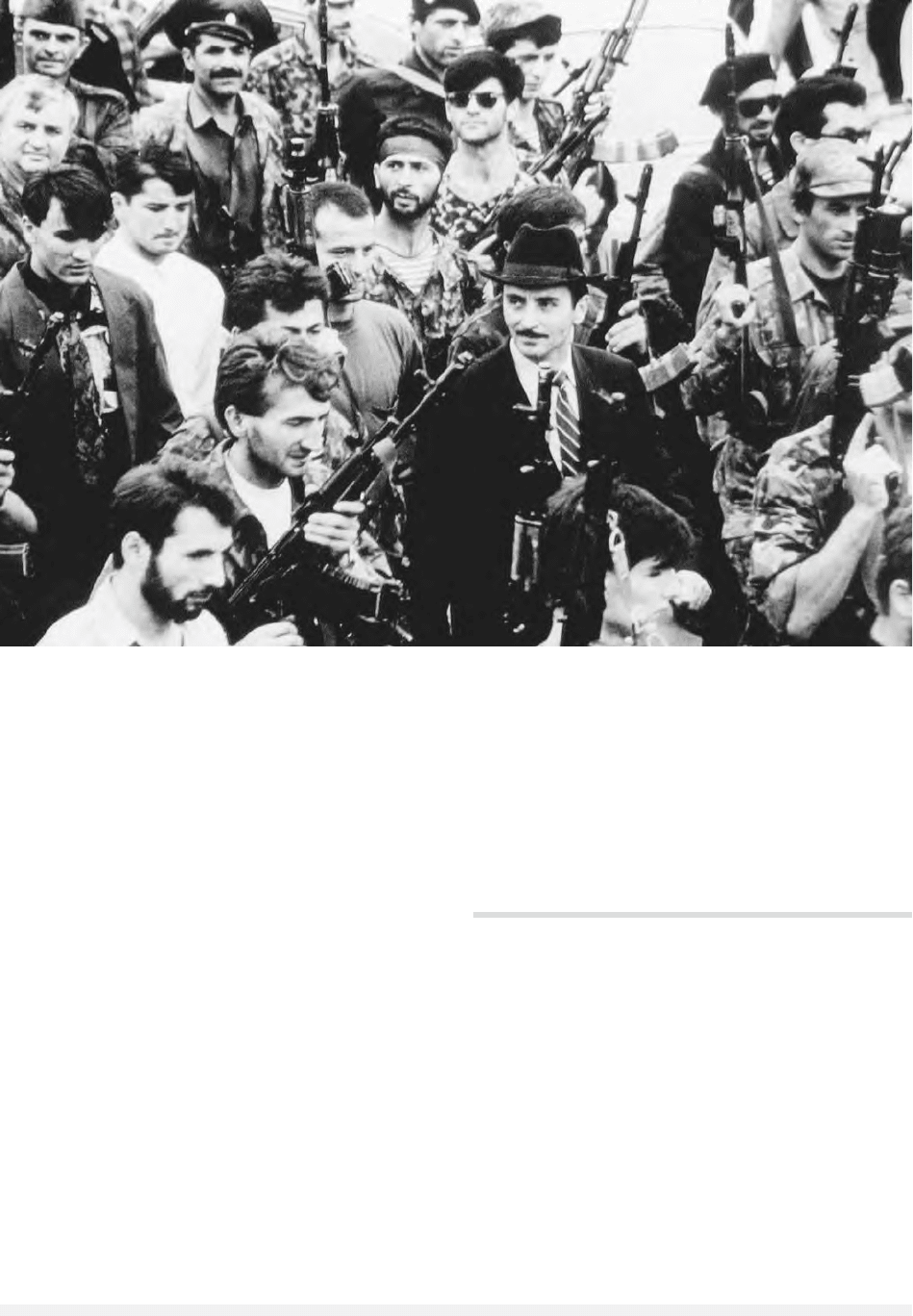

General Dzhokhar Dudayev and armed supporters in Chechnya. © Tchetchenie/CORBIS SYGMA

the Soviet Union, Dugin emerged as the chief ide-

ologue of the writer Edvard Limonov’s National-

Bolshevik Party, a fringe movement that cultivated

political ties with alienated youths. Dugin also be-

came a major figure in the “Red-Brown” opposi-

tion to the Yeltsin administration. He joined the

editorial board of Alexander Prokhanov’s Den (Day)

and then Zavtra (Tomorrow) after 1993. Dugin’s

writings combine mystical, conspiratorial, geopo-

litical, and Eurasian themes and draw heavily on

the notion of a conservative revolution. This ideol-

ogy emphasizes the Eurasian roots of Russian mes-

sianism and its fundamental antagonism with

Westernism and globalism, and outlines the way

in which Russia can go about creating an alterna-

tive to the Western “New World Order.” This al-

ternative is totalitarian in its essentials. Drawing

heavily upon German geopolitical theory and Lev

Gumilev’s Eurasianism, Dugin outlined his own

position in Foundations of Geopolitics: The Geopolit-

ical Future of Russia (1997). In 1999 Dugin cam-

paigned actively for the victory of a presidential

candidate who would embrace his ideas of an anti-

Western Eurasianism and supported Vladimir Putin

as the “ideal ruler for the present period.” Work-

ing closely with Gleb Pavlovsky, the Kremlin’s spin

doctor, Dugin actively developed an Internet em-

pire of connections to disseminate his message. In

the wake of Putin’s alliance with the United States

in the war against terrorism, Dugin has called into

question the president’s commitment to Eurasian-

ism and rejoined the opposition. Dugin has been

particularly adept at exploiting the Internet to

spread his message through a wide range of media.

See also: GUMILEV, LEV NIKOLAYEVICH; NATIONALISM IN

THE SOVIET UNION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Shenfield, Steven D. (2001). Russian Fascism: Traditions,

Tendencies, Movements. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Yasmann, Victor. (2001). “The Rise of the Eurasians.”

RFE/RL Security Watch 2 (17):1.

J

ACOB

W. K

IPP

DUMA

Known officially as the State Duma, this institu-

tion was the lower house of the Russian parlia-

mentary system from 1906 to 1917. In Kievan and

Muscovite times, rulers convened a “boyars’ duma”

of the highest nobles to provide counsel on major

policy issues. During the 1600s this institution fell

into disuse, but late-nineteenth-century liberals

lobbied for establishment of a representative body

to help govern Russia. After the Revolution of 1905,

Tsar Nicholas II agreed to form an advisory coun-

cil, the Bulygin Duma of August 1905. However,

revolutionary violence increased in the next two

months, and in his October 1905 Manifesto the tsar

reluctantly gave into the urgings of Sergei Witte to

grant an elected representative Duma with full leg-

islative powers.

This promise, plus other proffered reforms,

helped split the broad revolutionary movement,

winning over a number of moderates and liberals.

With violence waning, the tsar weakened the au-

thority of the proposed Duma by linking it with a

half-appointed upper house, the State Council; by

excluding foreign and military affairs and parts of

the state budget from its purview; and by weight-

ing election procedures to favor propertied groups.

Moreover, at heart Nicholas never accepted even

this watered-down version of the Duma as legiti-

mate, believing it an unwarranted infringement on

his divine right to rule. On the other hand many

reformers saw the Duma as the first step toward

a modern, democratic government and hoped to ex-

pand its authority.

FIRST AND SECOND

DUMAS, 1906–1907

Based on universal male suffrage over age twenty-

five, elections for the First Duma were on the whole

peaceful and orderly, although the indirect system

favored nobles and peasants over other groups. The

revolutionary Social Democrats and Socialist Rev-

olutionaries boycotted the elections, while the lib-

eral Constitutional Democrats (Cadets) conducted

the most effective campaign. The latter won a plu-

rality of members, and peasant deputies, though

usually unaffiliated with any party, proved anti-

government and reformist in their views. Perhaps

too rashly, the Cadet deputies pursued a con-

frontational policy toward the government, de-

manding radical land reform, extension of the

Duma’s budgetary authority, and a ministry re-

sponsible to the Duma. After three months of bit-

ter stalemate, Nicholas dissolved the Duma.

Elections to the Second Duma in the fall of 1906

worsened the political impasse. Although the

Cadets lost ground, radical parties participated and

elected several deputies, and the peasants again re-

DUMA

414

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

turned oppositionist representatives. Openly hostile

to the government, the Second Duma, like the first,

proved unable to find a compromise program and

was also dissolved after several months.

THIRD AND FOURTH

DUMAS, 1907–1917

Under the Fundamental Laws adopted in 1906 as

a semi-constitutional structure for Russia, the tsar

could dissolve the Duma and enact emergency leg-

islation in its absence. Using this authority, Prime

Minister Pyotr Stolypin decreed a new electoral sys-

tem for the Duma on June 3, 1907. He retained in-

direct voting but increased the weighting in favor

of the nobility from 34 to 51 percent and decreased

that of the peasantry from 43 to 22 percent. The

new law also reduced the number of non-Russian

deputies in the Duma by about two-thirds.

Stolypin achieved his goal of a more conservative

assembly, for the 1907 elections to the Third Duma

returned 293 conservative deputies, 78 Cadets and

other liberals, 34 leftists, and 16 nonparty deputies,

giving the government a comfortable working ma-

jority. The Octobrists, a group committed to mak-

ing the October Manifesto work, emerged as the

largest single bloc, with148 deputies. Consequently,

the Third Duma lasted out its full term of five

years, from 1907 to 1912.

Until his assassination in 1911, Stolypin suc-

ceeded for the most part in cooperating with the

Third Duma. The deputies supported an existing

agrarian reform program first drawn up by Witte

and instituted in 1906 by Stolypin that called for

dissolution of the peasant commune and establish-

ment of privately owned peasant plots, a complicated

procedure that was only partially completed when

World War I interrupted it. The government and

the Duma joined hands in planning an expansion

DUMA

415

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

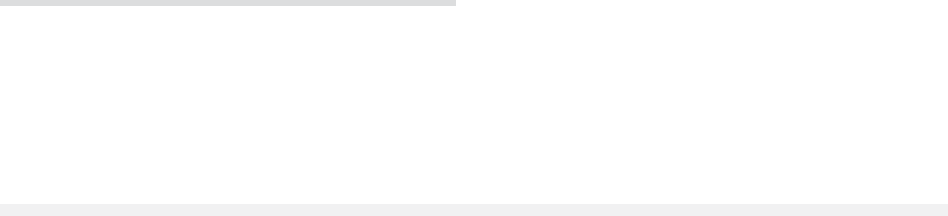

Nicholas II opens the Duma in St. Petersburg. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

of primary education designed to eradicate illiter-

acy and to have all children complete at least four

years of education. Although the State Council

blocked this legislation, the Ministry of Education

began on its own to implement it. Stolypin, a

staunch nationalist, also initiated legislative changes

limiting the authority of the autonomous Finnish

parliament and establishing zemstvos in western

Russia designed to subordinate Polish influence

there. Finally, without much success the Third

Duma propounded military reform, particularly

the improvement of naval administration. By 1912

the Octobrist Party had split, government minis-

ters were at odds, and rightist and nationalist in-

fluences dominated at court. Moreover, unrest was

growing among the urban population.

Elections to the Fourth Duma in late 1912 re-

turned a slightly more conservative body, but it

had hardly begun work when World War I erupted

in August 1914. An initial honeymoon between the

Duma and the government soon soured as military

defeats, administrative chaos, and ministerial in-

competence dismayed and irked the deputies. By

1915 a Progressive Bloc, formed under liberal lead-

ership, urged reforms and formation of a ministry

of public confidence, but it had little impact on the

government or the tsar. Shortly after the February

1917 Revolution broke out, Nicholas dissolved the

Duma, but its members reconstituted themselves

privately and soon formed a Temporary Commit-

tee to help restore order in Petrograd. After the

tsar’s abdication, this committee appointed the Pro-

visional Government that, though sharing some

aspects of power with the Petrograd Soviet, ran the

country until the outbreak of the Bolshevik Revo-

lution in the fall of 1917.

The Duma system opened the door to repre-

sentative government and demonstrated the polit-

ical potential of an elected parliament. This

experience helped legitimize the post-1991 effort to

establish democracy in Russia. Yet the four Dumas’

record was spotty at best. Useful legislation was

discussed and sometimes passed, but divisions

among the moderates, the inexperience of many

politicians, the reactionary influences of the State

Council along with some ministers and the tsar’s

entourage, and the visceral refusal of Nicholas II to

accept an independent legislature made it almost

impossible for the Duma to be the engine of reform

in old-regime Russia.

See also: CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY; FUNDA-

MENTAL LAWS OF 1906; NICHOLAS II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hosking, Geoffrey. (1973). The Russian Constitutional Ex-

periment: Government and Duma, 1907–14. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Pares, Sir Bernard. (1939). The Fall of the Russian Monar-

chy. London: Jonathan Cape.

Pinchuk, Ben-Cion. (1974). The Octobrists in the Third

Duma, 1907–12. Seattle: University of Washington

Press.

Tokmakoff, George. (1981). P. A. Stolypin and the Third

Duma: An Appraisal of Three Major Issues. Washing-

ton, DC: University Press of America.

J

OHN

M. T

HOMPSON

DUNAYEVSKY, ISAAK OSIPOVICH

(1900–1955), composer.

The Soviet composer Isaak Dunayevsky has

been compared to Irving Berlin and the other great

songsters of the 1930s and 1940s in America. Like

Berlin, he was a Russian-born Jewish composer

whose musical fertility gained him fame and

wealth in the realm of popular songs and musical

comedy for film and stage. Unlike the American,

he spent his most productive years under the

shadow of the Great Dictator, Josef Stalin. This

meant walking a tightrope from which a slight

breeze could topple him. That tightrope was Soviet

mass song, a genre embedded within a larger cul-

tural system known as Socialist Realism, the offi-

cially established code of creativity fashioned in the

early 1930s. Mass song required both political mes-

sage and broad popular appeal, a combination usu-

ally possible only in moments of urgent national

solidarity, as in wartime. Irving Berlin united these

elements successfully in the two world wars, and

in between settled for the unpolitical forms of love

ballads and novelty tunes. Dunayevsky had to sus-

tain the combination before, after, and during

World War II.

Dunayevsky, born near Kharkov in Ukraine,

began as a student of classical music. After the

Russian Revolution, he played with avant-garde

forms but eventually settled into composing pop-

ular music. His first big hit was the score for

Makhno’s Escapades (1927), a circus scenario that

mocked the civil war anarchist leader of a Ukrain-

ian partisan band opposed to the Bolsheviks.

Dunayevsky went on to compose some twenty film

scores, a dozen operettas, and music for two bal-

DUNAYEVSKY, ISAAK OSIPOVICH

416

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

lets and about thirty dramas. His lasting legacy is

the music from the enormously popular musical

films of the 1930s: Happy-Go-Lucky Guys, Circus,

Volga, Volga, and Radiant Road, all featuring the

singing star of the era, Lyubov Orlova, and directed

by her husband, Grigory Alexandrov. A fountain

of melody, Dunayevsky wove elements of folk

song, Viennese operetta styles, and jazz into opti-

mistic declamatory tunes that captivated Soviet lis-

teners for decades. The lyrics of the most famous

of these, “Vast Is My Native Land” (1936), from

the film Circus, celebrated the official image of Rus-

sia as a great nation, filled with free and happy cit-

izens. The Dunayevsky mode was overshadowed

somewhat during World War II, when more somber

and intimate songs prevailed. His postwar hit, the

music for Kuban Cossacks (1950), enhanced the pro-

paganda value of that film, which idealized the af-

fluence of Cossacks and peasants on the collective

farms of the Kuban region. Dunayevsky died in

1955.

See also: MOTION PICTURES; SOCIALIST REALISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jelagin, Juri. (1951). Taming of the Arts, tr. N. Wreden.

New York: Dutton.

Starr, S. Frederick. (1983). Red and Hot: The Fate of Jazz

in the Soviet Union. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Stites, Richard. (1992). Russian Popular Culture: Enter-

tainment and Society since 1900. Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press.

R

ICHARD

S

TITES

DUNGAN

The Dungans (Dungani) are descendants of the Hui

people who traveled to the northwestern provinces

of China, namely the Kansu and Shensi provinces

from the seventeenth to thirteenth centuries. Orig-

inally scholars, merchants, soldiers, and handi-

craftsmen, they gradually intermarried with the

Han Chinese. Although they learned the Chinese

language, they also retained their knowledge of the

Arabic language and Muslim faith. From 1862 to

1878 the Hui people rebelled, and the Chinese em-

peror ruthlessly suppressed them. Three groups of

Hui rebels fled across the Tien Shan mountains into

Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. Those who lived in

the Kansu province settled in Kyrgyzstan and to-

day number approximately 30,000. Rebels from

the Shensi province generally settled in Kazakhstan,

where they number roughly 37,000. The third

group fled to the Russian Empire later in 1881.

After their exodus, the rebels (named Dolgans

by the Russians) cut off all contact with China, but

nevertheless continued to refer to themselves as

Chinese Muslims (Hui-Zu). They settled mainly

along the Chu River on the banks of which the Kyr-

gyz capital of Bishkek (named Frunze in the Soviet

period) is situated. This river also forms part of the

border between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

The Dungan language is Mandarin Chinese, but

with heavy influence of Persian (Farsi), Arabic, and

Turkish. In addition to Dungani, many speak Kyr-

gyz, and the younger ones also speak Russian.

Dungani is written not in Chinese characters but

Cyrillic script, and has three tones rather than four.

Generally, the Dungans in Kyrgyzstan are less

devoted as Muslims than their kin in Kazakhstan.

All Dungans subscribe to the Hanafite Muslim

school of thought, established by the theologian

Imam Abu Hanifa (699–767), who has shaped the

Central Asian form of Islam. While elderly Dun-

gans strictly observe Islamic law, their younger off-

spring usually ignore Islam until they reach their

forties. Elders run village mosques, and the clergy-

men are supported by property taxes and the wor-

shipers’ donations. At present, although the Bible

has been translated into Dungani, no Dungans are

Christians. Living mostly in the river valleys, the

Dungans are primarily farmers and cattle breeders,

although some grow opium.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; ISLAM; NATIONALITIES POLICIES,

SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dyer, Svetlana Rimsky-Korsakoff. (1979). Soviet Dungan

Kolkhozes in the Kirghiz SSR and the Kazakh SSR. Can-

berra: Australian National University Press.

Israeli, Raphael. (1982). The Crescent in the East: Islam in

Asia Major. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Curzon Press.

Javeline, Debra. (1997). Islam Yes, Islamic State No for

Muslim Kazakhstanis. Washington, DC: Office of Re-

search and Media Reaction, USIA.

Kim, Ho-dong. (1986). “The Muslim Rebellion and the

Kashghar Emirate in Chinese Central Asia,

1864–1877.” Ph.D. diss., Harvard University.

DUNGAN

417

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Li, Shujiang, and Luckert, Karl W., (1994). Mythology and

Folklore of the Hui, a Muslim Chinese People. Albany:

State University of New York Press.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

DUROVA, NADEZHDA ANDREYEVNA

(1783–1855), cavalry officer and writer.

Nadezhda Durova (“Alexander Alexandrov,”

“Cavalry Maiden”) served in the tsarist cavalry

throughout Russia’s campaigns against Napoleon.

Equally remarkably, in the late 1830s she published

memoirs of those years (The Cavalry Maiden [Kava-

lerist-devitsa], 1836; Notes [Zapiski], 1839) and fic-

tion in the Gothic/Romantic vein drawn from her

military experience, much of it narrated by a fe-

male officer. At first she masqueraded as a boy, but

in December 1807 Alexander II learned of the

woman soldier in his army and, impressed by ac-

counts of her courage in the East Prussian cam-

paign, gave her a commission in the Mariupol

Hussars under his name, Alexandrov. In 1811

Durova transferred to the Lithuanian Uhlans. Dur-

ing the Russian retreat to Moscow in 1812 she

served in the rear guard, engaging in repeated

clashes with the French. Bored with peacetime ser-

vice and annoyed at not receiving promotion,

Durova resigned her commission in 1816. She be-

came briefly famous after The Cavalry Maiden was

published, an experience she described laconically

in “A Year of Life in St. Petersburg” (God zhizni v

Peterburge, 1838), before retreating to provincial ob-

scurity in Yelabuga, where she was known as an

amiable eccentric woman with semi-masculine

mannerisms and dress. Durova’s memoirs omit in-

convenient facts (an early marriage; the birth of

her son), but she was a gifted storyteller, and her

tales are rich in astute, humorous observations of

military life as an outsider saw it. Her biography,

heavily romanticized, became a propaganda tool

during World War II, but The Cavalry Maiden was

reprinted in full in the Soviet Union only in the

1980s.

See also: FRENCH WAR OF 1812; MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA;

NAPOLEON I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Durova, Nadezhda. (1988). The Cavalry Maiden, ed. and

tr. Mary Fleming Zirin. Bloomington: Indiana Uni-

versity Press.

Gheith, Jehanne. (1999). “Durova.” In Russian Literature

in the Age of Pushkin and Gogol: Prose, ed. Christine

A. Rydel. Dictionary of Literary Biography, 1999.

Detroit: Gale Research.

M

ARY

Z

IRIN

DVOEVERIE

“Dvoeverie”—“double-belief” or “dual faith”—is a

highly influential concept in Russian studies, which

began to be questioned in the 1990s. Since the

1860s, historians have used it to describe the con-

scious or unconscious preservation of pagan beliefs

and/or rituals by Christian communities (generally

as a syncretic faith containing Christian and pagan

elements; a form of peasant/female resistance to

elite/patriarchal Christianity; or two independent

belief-systems held concurrently). This concept has

colored academic perception of Russian medieval

(and often modern) spirituality, leading to a pre-

occupation with identifying latent paganism in

Russian culture. It has often been considered a

specifically Russian phenomenon, with the me-

dieval origins of the term cited as evidence.

This definition of dvoeverie is supported in part

by one text, the eleventh-century Sermon of the

Christlover, but its notable absence in other anti-pa-

gan polemics (including those regularly cited as ev-

idence of double-belief), plus many uses of the word

in different contexts, lead one to conclude that the

term was not originally understood in this way.

Dvoeverie probably originated as a calque from

Greek, via the translated Nomocanon. While at least

six Greek constructions are translated as dvoeverie

or a lexical derivative thereof, the common thread

is that of being “in two minds”; being unable to

decide or agree, or being unable to perceive the true

nature of something. In the majority of these cases,

there is no question of there being two faiths in

which the practitioner believes simultaneously or

even alternately, and sometimes no question of re-

ligious faith at all.

In other pre-Petrine texts, dvoeverie means “du-

plicitous” or “hypocritical,” or relates to an inabil-

ity or unwillingness to identify solely with the one

true and Orthodox faith. Lutherans and those frat-

ernizing with Roman Catholics, rather than semi-

converted heathens, were the target of this pejorative

epithet.

See also: ORTHODOXY; PAGANISM

DUROVA, NADEZHDA ANDREYEVNA

418

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Levin, Eve. (1993) “Dvoeverie and Popular Religion.” In

Seeking God: The Recovery of Religious Identity in Or-

thodox Russia, Ukraine, and Georgia ed. S. K. Batalden.

DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

Rock, Stella. (2001). “What’s in a Word? A Historical

Study of the Concept Dvoeverie.” Canadian-American

Slavic Studies, 35(1):19-28.

S

TELLA

R

OCK

DVORIANSTVO

The term dvorianstvo is sometimes translated as

“gentry,” but often historically such a translation

is simply incorrect. At other times, such as between

the years 1667 and 1700, and again after 1762 (or

1785) until 1917, “gentry” is misleading but not

totally wrong.

The term has its origins in the later Middle Ages

in the word dvor, “princely court.” In that histor-

ical context, the dvorianstvo were those who

worked at the court of a prince. Originally such

people might be free men, or they might be slaves

of the prince or someone else. Moreover, these men,

most of whom were cavalrymen and a few of

whom were administrators, were wholly depen-

dent on the grand prince for their positions, sta-

tus, and livelihoods. They did not have lands, but

lived off booty, funds collected in the line of gov-

ernmental duty, and funds collected by others for

the sovereign’s treasury. Their social origins were

most diverse. A handful were princes (descendants

of one of the princely houses circulating in Rus’:

the Rus’ Riurikids, the Lithuanian Gedemids, or

Turkic/Mongol nobility), some were slaves, others

were of diverse origins. A prince or nobleman had

no right to be a member of the dvorianstvo, for

such men got their positions because they were

selected by the grand prince and served at his

pleasure. Promotion within the dvorianstvo was

meritocratic, however service might be defined.

Membership in the dvorianstvo conferred no spe-

cial status, and in law such men could be punished

like everyone else, including flogging.

The origins of the early dvorianstvo are ob-

scure, but around 1480, the Moscow government

began to formalize the situation when it initiated

the first service class revolution after the annexa-

tion of Novgorod. Moscow initiated the service land

system (pomestie) on the lands annexed from Nov-

gorod, and then gradually extended it to the entire

Muscovite state. By 1556 most of the inhabited

land (which did not belong to the church) in cen-

tral Muscovy was included in the fund that had to

support cavalrymen. The cavalrymen based in

Moscow were the upper service class; those in the

provinces were the middle service class. (Members

of the lower service class did not have lands for

their support and lived off government cash

salaries, and their own extra-military employment;

they were arquebusiers—later in the seventeenth

century musketeers, fortress gatekeepers, artillery-

men, some cossacks, and others.) Members of both

the upper and middle service classes comprised the

dvorianstvo and were the core of the army. They

had to render military service almost every year,

typically on the southern frontier against the

Tatars, Nogais, Kalmyks, Kazakhs, and others who

raided Muscovy in search of slaves and other booty.

The dvorianstvo had to render military service on

the western frontier whenever called against the

Poles, Lithuanians, and Swedes, where the prizes

for the victors were landed territory and booty (in-

cluding slaves) of every sort.

Between 1480 and 1667 the life of the dvo-

rianstvo was very hard. Military service was basi-

cally for life, from about age fifteen until immobility

compelled retirement from service. Those who

could no longer serve as cavalrymen still could be

called upon to render “siege service,” which meant

standing up in castles and shooting arrows out at

besieging enemies. In the seventeenth century gun-

powder arms replaced the arrows. Only when the

member of the dvorianstvo was dead or could only

be carried around in a litter was he allowed to re-

tire from service. Members of the provincial dvo-

rianstvo had the ranks of provincial dvorianin and

syn boyarsky and were supported primarily by a

handful of peasant households (government cash

stipends were meant to purchase military goods in

the market, such as cavalry horses, sabers, and

guns in the seventeenth century and later). In the

provinces they lived little better than most of their

peasants and until the post–1649 period were as

illiterate as their peasants also. The capital dvo-

rianstvo, living in Moscow, had the ranks of bo-

yarin, okol’nichii, stol’nik, striapchii, and Moscow

dvorianin, lived the same rigorous lives as did their

country cousins, although with higher incomes.

Both rose in the dvorianstvo on the basis of per-

ceived meritocratic service by petitioning for pro-

motion. Because of their precarious economic

positions, the provincial dvorianstvo were highly

conscious of how many rent-paying peasants they

had. Should their peasants depart, they were in

DVORIANSTVO

419

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

straits. They were the ones who forced the enserf-

ment of the peasantry between the 1580s and 1649.

The Ulozhenie of 1649, which completed the en-

serfment by binding the peasants to the land, was a

triumph for the provincial dvorianstvo, and a defeat

for the capital dvorianstvo, who profited from peas-

ant mobility. The Thirteen Years’ War (1654–1667)

delivered the coup de grace to the middle service class

provincial dvorianstvo by illustrating definitively the

obsolescence of bow-and-arrow warfare. Moreover,

much of the dvorianstvo fell into Turkish captivity,

where many of them remained for a quarter cen-

tury. From then until 1700, the dvorianstvo occa-

sionally fought the Turks, but otherwise did little to

merit their near-monopoly over serf labor. Reflect-

ing the fact that Russia was a very poor country

with a very unproductive agriculture, the dvo-

rianstvo comprised less than 1 percent of the popu-

lation, a much smaller fraction than in other

countries. After the annexation of Poland, the dvo-

rianstvo of the Russian Empire rose by 1795 to 2.2

percent of the population.

At the battle of Narva in 1700 Charles XII de-

feated Peter the Great, who responded by launch-

ing the second service class revolution. This meant

putting the dvorianstvo back in harness. In 1722

he introduced the Table of Ranks, which formal-

ized the Muscovite system of promotion based on

merit. Rigorous lifetime military or governmental

service was compulsory until 1736, when the ser-

vice requirement for the dvorianstvo was reduced

to twenty-five years. In 1740 they could choose

between military or civil service. Then in 1762 Peter

III freed the dvorianstvo from all service require-

ments. His wife Catherine II in 1785 promulgated

the Charter of the Nobility, whose infamous Arti-

cle 10 freed the dvorianstvo from corporal punish-

ment and thus made them a privileged caste. The

measures of 1762 and 1785 created the conditions

for the Russian dvorianstvo to begin to look like

gentry living elsewhere in Europe west of Russia.

The years 1762 to 1861 were the “Golden Age”

of the dvorianstvo. Its members were the poten-

tially leisured, privileged members of society. Many

differed little from peasants; a few were extraordi-

narily rich. They were the bearers and creators of

culture. The Achilles heel of the dvorianstvo was

its penchant for debt to finance excessive con-

sumption, including imported goods that were

equated with modernization and Westernization.

The emancipation of the peasantry in 1861 initi-

ated the decline of the dvorianstvo, whose mem-

bers lost their slave-owner-like control over their

peasants. The dvorianstvo was compensated (ex-

cessively) for the land granted to the peasants, but

debts were deducted from the compensation. Other

reforms gradually cost the dvorianstvo their con-

trol over the countryside. Their inability to man-

age their funds and estates and in general to cope

with a modernizing world is metonymically por-

trayed in Anton. P. Chekhov’s play The Cherry Or-

chard, which came to be the name of the era for

the dvorianstvo. By the Revolution of 1917 the

dvorianstvo lost control over their initial bastion,

the army, and nearly all other sectors of life as well.

In the summer of 1917 the peasantry seized much

of the dvorianstvo land, which was all confiscated

when the Bolsheviks took power. Some members

of the dvorianstvo joined the Whites and died in

opposition to the Bolsheviks, while others emi-

grated. Those who remained in the USSR were de-

prived of their civil rights until 1936.

See also: BOYAR; CHARTER OF THE NOBILITY; LAW CODE

OF 1649; MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA; SYN BOYARSKY;

TABLE OF RANKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blum, Jerome. (1961). Lord and Peasant in Russia from

the Ninth to the Nineteenth Century. Princeton, NY:

Princeton University Press.

Hellie, Richard. (1971). Enserfment and Military Change in

Muscovy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Hellie, Richard. (1982). Slavery in Russia 1425–1725.

Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

R

ICHARD

H

ELLIE

DYACHENKO, TATIANA BORISOVNA

(b. 1960), adviser to her father, President Boris

Yeltsin.

Tatiana Dyachenko became an adviser to her

father, President Boris Yeltsin, in the last few years

of his rule. Trained as a mathematician and com-

puter scientist, she worked in a design bureau of

the space industry until 1994. She then worked for

the bank Zarya Urala (Ural Dawn).

In the early 1990s her father’s ghostwriter

Valentin Yumashev introduced her to the Mafia-

connected businessman Boris Berezovsky. The lat-

ter courted her with attention and lavish presents,

and handed her father three million dollars that he

claimed were royalties on Yeltsin’s second volume

DYACHENKO, TATIANA BORISOVNA

420

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

of memoirs. This episode launched the rise of the

businessmen oligarchs who became highly influ-

ential in Yeltsin’s administration.

In February 1996, with a popular approval

rating in single digits as he began his ultimately

successful run for reelection, Yeltsin appointed Dy-

achenko to his campaign staff. Here she worked

closely with key oligarchs and the campaign direc-

tor Anatoly Chubais. That summer, she facilitated

her father’s ouster of his hitherto most trusted aide,

Alexander Korzhakov, and then the ascent of

Chubais to head the Presidential Administration.

In June 1997 Yeltsin formally appointed her

one of his advisers, responsible for public relations.

In 1998 she was named a director of Russia’s lead-

ing TV channel, Public Russian Television (ORT),

controlled by Berezovsky.

In 1999, as Yeltsin’s power ebbed, Dyachenko’s

lifestyle fell under scrutiny with the unfolding of

various top-level scandals. For example, the Swiss

firm Mabetex was revealed to have paid major kick-

backs to Kremlin figures, with Dyachenko and

other Yeltsin relatives allegedly having spent large

sums by credit card free of charge.

After her father’s resignation in December 1999,

Dyachenko continued to be an influential coordi-

nator of her father’s political and business clan and

an unpaid adviser to the head of Vladimir Putin’s

Presidential Administration Alexander Voloshin.

Dyachenko has three children, one by each of

her three husbands.

See also: YELTSIN, BORIS NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Klebnikov, Paul. (2000). Godfather of the Kremlin: Boris

Berezovsky and the Looting of Russia. New York: Har-

court.

Yeltsin, Boris. (2000). Midnight Diaries. New York: Pub-

lic Affairs.

P

ETER

R

EDDAWAY

DYAK

State secretary, professional administrator.

The dyak (state secretary) spearheaded Mus-

covy’s bureaucratic transformation from the late

1400s into the Petrine era. Moscow professional ad-

ministrators, seventeenth-century dyaks guaran-

teed daily chancellery operation, served in the gov-

erning tribunals, and supervised the clerks. Dyaks

authorized document compilation, verified and

signed documents after clerks drafted them, and

sometimes wrote up documents.

Technical expertise was the dyak’s sine qua non.

Talent and experience governed promotion and re-

tention of dyaks. Of appanage slave origin, the

dyaks were docile, functionally literate, efficient pa-

perwork organizers, and artificers of chancellery

document style and formulae. Less than eight hun-

dred dyaks served in seventeenth-century chancel-

leries, annually between 1646 and 1686; forty-six

(or 6%) of all dyaks achieved Boyar Duma rank.

The decrees of 1640 and 1658 formally converted

dyaks and clerks into an administrative caste by

guaranteeing that only their scions could become

professional administrators. Dyaks’ sons began as

clerks, but father-son dyak lineages were uncom-

mon, as few clerks ever became dyaks.

Almost half of the chancellery dyaks (some

Moscow dyaks received no administrative postings)

worked in one chancellery. Dyaks worked on av-

erage 3.5 years per state chancellery, their average

earnings decreasing from one hundred rubles in the

1620s to less than ninety rubles in the 1680s. They

could also receive land allotments as pay. In con-

trast, counselor state secretaries could earn two

hundred rubles in the 1620s, and their salaries

nearly doubled in the 1680s.

Seventeenth-century dyaks’ social position de-

clined, although their technical skills did not. Dyaks

served also in provincial administrative offices, and

numbered between 33 to 45 percent of their chan-

cellery brethren. Few ever entered capital service.

See also: BOYAR DUMA; CHANCELLERY SYSTEM; PODY-

ACHY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brown, Peter B. (1978). “Early Modern Russian Bureau-

cracy: The Evolution of the Chancellery System from

Ivan III to Peter the Great, 1478–1717.” Ph.D. diss.,

University of Chicago.

Plavsic, Borovoi. (1980). “Seventeenth-Century Chanceries

and Their Staffs.” In Russian Officialdom: The Bu-

reaucratization of Russian Society from the Seventeenth

to the Twentieth Century, eds. Walter McKenzie Pint-

ner and Don Karl Rowney. Chapel Hill: University

of North Carolina Press.

P

ETER

B. B

ROWN

DYAK

421

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

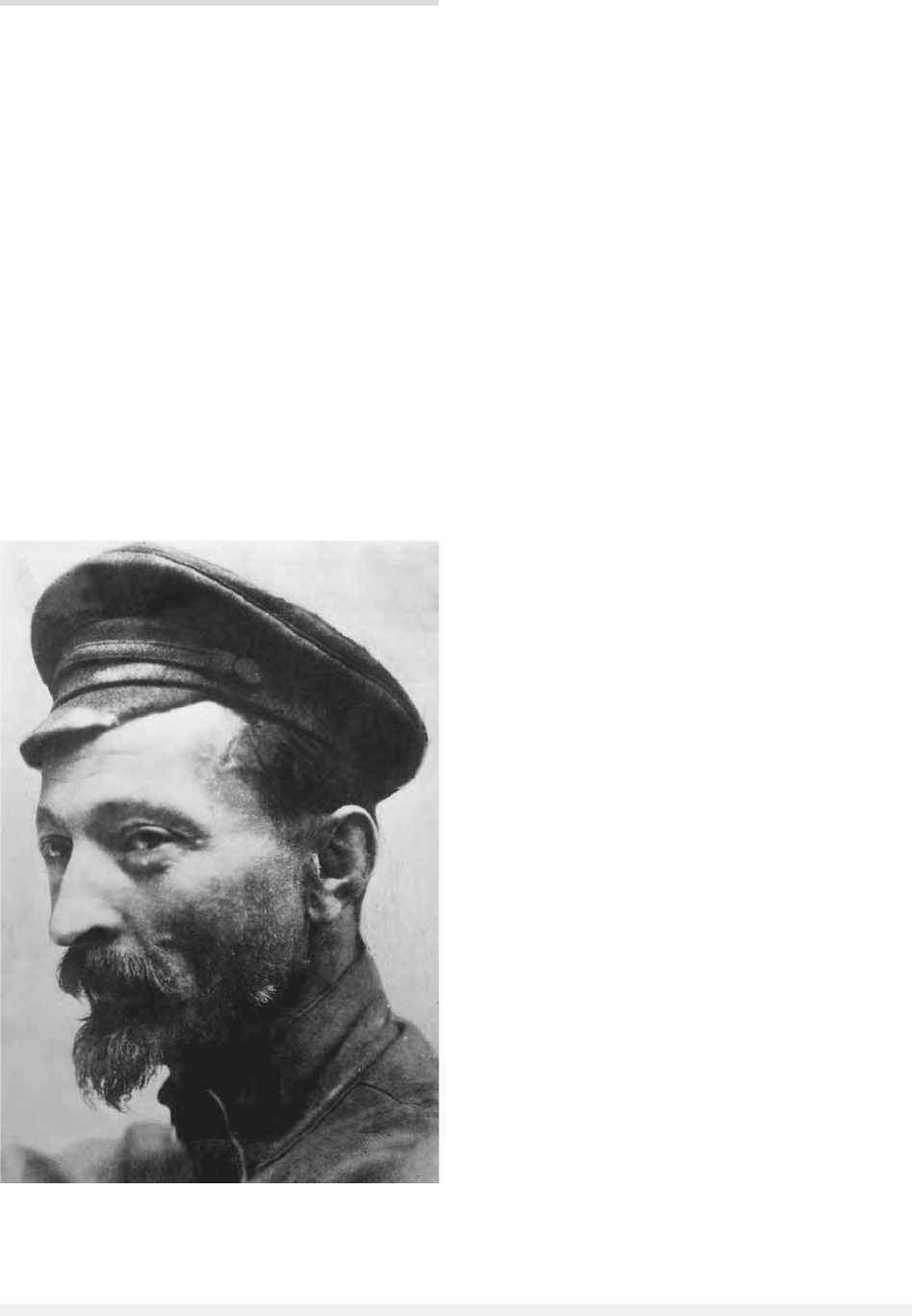

DZERZHINSKY, FELIX EDMUNDOVICH

(1877–1926), Polish revolutionary; first head of the

Soviet political police.

Felix Dzerzhinsky descended from a Polish

noble family of long standing, with known pa-

ternal roots in seventeenth-century historic

Lithuania. His father Edmund taught physics and

mathematics at the male gymnasium in Tagan-

rog before retiring to the family estate located

in present-day Belarus. His mother, Helena Janus-

zewska, came from a well-connected aristocratic

family. After Edmund’s death in 1882, she raised

Felix in a devout Roman Catholic and Polish pa-

triotic environment. A sheltered child, Dzerzhin-

sky was earmarked by his mother for the

priesthood, but his participation in a series of pro-

gressively radical student circles in Vilnius led to

his expulsion from the gymnasium two months

before graduation in 1896. His subsequent in-

volvement with the fledgling Lithuanian Social

Democratic Party ended with his arrest in Kaunas

in 1897, the first of six arrests in his revolution-

ary career.

Dzerzhinsky was exiled to and escaped from

Siberia on three different occasions. Following his

first escape in 1899, he resurfaced in Warsaw,

where he founded the Social Democracy of the

Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL) by

merging remnants of previously existing social de-

mocratic organizations in Warsaw and Vilnius.

Over the next dozen years, despite long periods of

confinement, Dzerzhinsky constructed the appa-

ratus of a conspiratorial organization that guided

the SDKPiL through and beyond the revolutionary

turmoil of 1905–1907. An ideological disciple of

Rosa Luxemburg, Dzerzhinsky was a permanent

fixture on the party’s executive committee and

played a principal role in defining the SDKPiL’s re-

lations with the Menshevik and Bolshevik factions

of the Russian Social Democratic Workers’ Party

(RSDRP). Following the SDKPiL’s formal unifica-

tion with the Russian party in 1906, Dzerzhinsky

represented the former on the RSDRP Central Com-

mittee and editorial board.

Dzerzhinsky’s final arrest in Warsaw in 1912

resulted in successive sentences to hard labor. He

was released from the Moscow Butyrki prison by

the March 1917 revolution. Dzerzhinsky was

soon caught up in the Russian revolutionary

whirlwind, first in Moscow, then in Petrograd, at

which time he entered the Bolshevik Central Com-

mittee. Dzerzhinsky played a key role in the Mil-

itary Revolutionary Committee that carried out

the October 1917 coup d’état, and he assumed re-

sponsibility for security of the Bolshevik head-

quarters at the Smolny Institute. From there it

was a logical step for Dzerzhinsky to head an ex-

traordinary commission, the Cheka, to act as the

shield and sword of the Bolshevik regime against

its enemies and opponents. Under Dzerzhinsky,

the Cheka became more than a political police force

and instrument of terror. Instead, Dzerzhinsky’s

obsessive personality and dynamic organizational

talents drove the Cheka into almost every area of

Soviet life, from disease control and social philan-

thropy to labor mobilization and management of

the railroads. Following the civil war, Dzerzhin-

sky aligned himself with Bukharin’s faction and,

as Chairman of the Supreme Economic Council,

became a vigorous proponent of the New Economic

Policy. Physically weakened by years spent in var-

DZERZHINSKY, FELIX EDMUNDOVICH

422

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

“Iron Felix” Dzerzhinsky, the feared chief of the Bolshevik

political police. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS