Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Officially the DSR never registered as a party,

first because of identification with “opposition from

outside the system,” then because of low numbers

and lack of organizational structures in the

provinces. In 1993 Novgorodskaya entered the bal-

lot in a single-mandate district as a candidate from

the bloc Russia’s Choice; in 1995 on the list of the

Party of Economic Freedom, which a significant

portion of the DSR entered in order to receive offi-

cial status. In the 1999 elections, the DS joined with

“A Just Cause,” but with the registration of the

latter, left for the Union of Right Forces (SPS). In

the 2000 presidential elections, the DS supported

Konstantin Titov. Since then, the DS’s only ap-

pearances in the news have been thanks to Nov-

gorodskaya’s activity and high profile.

See also: PERESTROIKA; POLITICAL PARTY SYSTEM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

McFaul, Michael. (2001). Russia’s Unfinished Revolution:

Political Change from Gorbachev to Putin. Ithaca, NY:

Cornell University Press.

McFaul, Michael, and Markov, Sergei. (1993). The Trou-

bled Birth of Russian Democracy: Parties, Personalities,

and Programs. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution

Press.

Reddaway, Peter, and Glinski, Dmitri. (2001). The Tragedy

of Russia’s Reforms: Market Bolshevism against Democ-

racry. Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press.

N

IKOLAI

P

ETROV

DEMOCRATIZATION

While modern times have seen more than one,

however partial, attempt to democratize Russia, de-

mocratization in the narrow sense refers to policies

pursued by Mikhail Gorbachev and his closest as-

sociates, roughly from 1987 to 1991.

The language of democratization was widely

employed within a one-party context by Gor-

bachev’s predecessors, most notably by Nikita

Khrushchev. Yet their interpretations of demokrati-

zatsiya and democratizm diverged fundamentally

from universal definitions of democracy. “Soviet

democratization” implied increased public discus-

sions, mostly on economic and cultural issues; in-

creased engagement of Communist Party (CPSU)

leaders with ordinary people; and some liberali-

zation, namely, expansion of individual freedoms

and relaxation of censorship. However, electoral

contestation for power among different political

forces was out of the question. The openly stated

goals of democratization Soviet-style included

reestablishing feedback mechanisms between the

leadership and the masses over the head of the bu-

reaucracy; encouraging public pressure to improve

the latter’s performance; and improving the psy-

chological and moral climate in the country, in-

cluding confidence in the CPSU leadership, with

expectations of a resulting increase in labor pro-

ductivity. Additional, unspoken goals ranged from

strengthening a new leader’s position, through

public discussion and support, vis-à-vis conserva-

tive elements, to promoting Moscow’s interna-

tional image and its standing vis-à-vis the West.

Gorbachev’s initial steps followed this pattern,

relying, at times explicitly, upon the legacy and ex-

perience of Khrushchev’s thaw; the official slogan

of the time promised “more democracy, more so-

cialism.” Soon, however, Gorbachev pushed democ-

ratization toward full-scale electoral democracy. The

reforms sparked demands for ideological pluralism

and ethnic autonomy. As the momentum of re-

form slipped from under his control, Gorbachev’s

own policies were increasingly driven by improvi-

sation rather than long-term planning. Emerging

nonparty actors—human rights organizations, in-

dependent labor unions, nationalist movements,

entrepreneurs, criminal syndicates, proto-parties,

and individual strongmen such as Boris Yeltsin—

as well as old actors and interest groups, with new

electoral and lobbying vehicles at their disposal, in-

troduced their own goals and intentions, often

vaguely understood and articulated, at times mis-

represented to the public, into Gorbachev’s original

design of controlled democratization.

Preliminary steps toward electoral democracy

at the local level were taken in the wake of the

CPSU Central Committee plenum of January 1987

that shifted perestroika’s emphasis from economic

acceleration to political reform. A subsequent Polit-

buro decision, codified by republican Supreme So-

viets, introduced experimental competitive elections

to the soviets in multi-member districts. They were

held in June 1987 in 162 selected districts; on av-

erage, five candidates ran for four vacancies; elec-

tion losers were designated as reserve deputies,

entitled to all rights except voting. Bolder steps to-

ward nationwide electoral democracy—multicandi-

date elections throughout the country and

unlimited nomination of candidates (all this while

preserving the CPSU rule, with the stated intent of

DEMOCRATIZATION

373

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

increasing popular confidence in the Party)—were

enunciated by Gorbachev at the Nineteenth CPSU

Conference in June 1988. The Conference also ap-

proved his general proposals for a constitutional

change to transfer some real power from the CPSU

to the representative bodies.

Seeking to redesign the Union-level institu-

tions, some of Gorbachev’s advisers suggested

French-style presidentialism, while others harked

back to the radical participatory democracy of the

1917 soviets, when supreme power was vested in

the hands of their nationwide congresses. Idealisti-

cally minded reformers envisaged this as a return

to the unspoiled Leninist roots of the system. Gor-

bachev initially opted for the latter, in the form of

the Congress of People’s Deputies, a 2,250-mem-

ber body meeting once (and subsequently twice)

per year. Yet only 1,500 of its deputies were di-

rectly elected in the districts, while 750 were picked

by public organizations (from Komsomol to the

Red Cross), including one hundred by the CPSU

Central Committee, a precautionary procedure

that violated the principle of voters’ equality. The

Congress was electing from its ranks a working

legislature, the bicameral Supreme Soviet of 542

members (thus bearing the name of the preexist-

ing institution that had been filled by direct how-

ever phony elections). The constitutional authority

of the latter was designed to approximate that of

Western parliaments, having the power to confirm

and oversee government members.

The relevant constitutional amendments were

adopted in December 1988; the election to the

Congress took place in March 1989. This was the

first nationwide electoral campaign since 1917,

marked—at least in major urban centers and most

developed areas of the country—by real competi-

tion, non-compulsory public participation, mass

volunteerism, and high (some of them, arguably,

unrealistic) expectations. Though more than 87

percent of those elected were CPSU members, by

now their membership had little to do with their

actual political positions. The full ideological spec-

trum, from nationalist and liberal to the extreme

left, could be found among the rank and file of the

Party. On the other hand, wide cultural and eco-

nomic disparities resulted in the extremely uneven

impact of democratization across the Union (thus,

in 399 of the 1,500 districts only one candidate was

running, while in another 952 there were two, but

in this case competition was often phony). And

conservative elements of the nomenklatura were

able to rig and manipulate the elections, in spite of

the public denunciations, even in advanced metro-

politan areas, Moscow included. Besides, the two-

tier representation, in which direct popular vote

was only one of the ingredients, was rapidly dele-

gitimized by the increasingly radical understand-

ing of democracy as people’s power, spread by the

media and embraced by discontented citizenry.

The First Congress (opened in Moscow on May

25, 1989, and chaired by Gorbachev), almost en-

tirely broadcast live on national TV, was the peak

event of democratization “from above,” as well as

the first major disappointment with the realities of

democracy, among both the reform-minded estab-

lishment and the wider strata. Cultural gaps and

disparities in development between parts of the

Union were reflected in the composition of the

Congress that not only was extremely polarized in

ideological terms (from Stalinists to radical West-

ernizers and anti-Russian nationalists from the

Baltics), but also bristled with social and cultural

hostility between its members (e.g., representatives

of premodern Central Asian establishments versus

the emancipated Moscow intelligentsia). Advocates

of further democratization (mostly representing

Moscow, St. Petersburg, the Baltic nations, Ukraine,

and the Caucasus, and ranging from moderate Gor-

bachevites to revolutionary-minded dissidents), who

later united in the Interregional Deputies Group

(IDG) and were widely described as “the democ-

rats,” had less than 250 votes in the Congress and

even a smaller proportion in the Supreme Soviet.

The bulk of the deputies had no structured politi-

cal views but were instinctually conservative; they

were famously branded by an IDG leader Yuri

Afanasiev as “the aggressively obedient majority.”

The resulting stalemate compelled Gorbachev to

abandon legislative experiments and shift to a pres-

idential system, while the democrats (many of

them recently high-ranking CPSU officials, with

only a handful of committed dissidents) also turned

their backs on the Congress to lead street rallies and

nascent political organizations, eventually winning

more votes and positions of leadership in republi-

can legislatures and city councils.

Thus, democratization’s center of gravity shifted

away from the all-Union level. The key events of

this stage were the unprecedentedly democratic re-

publican and municipal elections (February–March

1990), with all deputies now elected directly by

voters, and the abolition of Article 6 of the USSR

Constitution that had designated the CPSU as “the

leading and guiding force of Soviet society and the

nucleus of its political system” with the right to

DEMOCRATIZATION

374

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

determine “the general policy of the country.” The

elimination of this article, demanded by the IDG

and mass rallies and eventually endorsed by Gor-

bachev, was approved by the Congress on March

13, 1990, thus removing constitutional obstacles

for a multi-party system—arguably the major and

perhaps the only enduring institutional change of

the period achieved through public pressure.

From that time issues of democratization yielded

center stage to institutional collapse and economic

reforms. A major transitional point was Gorbachev’s

decision to become USSR president through a par-

liamentary vote, instead of running in direct na-

tionwide elections. As a result, his presidency and

other Union-wide institutions lagged behind re-

publican authorities in terms of their democratic

legitimacy. This was accentuated by Yeltsin’s elec-

tion as Russian president (June 1991), the first di-

rect popular election of a Russian ruler, which

initially endowed him with exceptional legitimacy,

but with no effective mechanisms of accountabil-

ity and restraint. And the disbanding of the Soviet

Union (December 1991) had an ambivalent rela-

tionship to democratization, for while it was de-

cided by democratically elected leaders, Yeltsin had

no popular mandate for such a decision; to the con-

trary, it nullified the results of the Union-wide ref-

erendum of March 1991, where overwhelming

majorities in these republics voted for the preser-

vation of the Union.

As a result of the events of the years 1988–1991,

Russia acquired and institutionalized the basic fa-

cade of a minimalist, or procedural democracy,

without providing citizens with leverage for wield-

ing decisive influence over the authorities. The dis-

illusionment with democratization has been shared

both in the elite—some viewing it as a distraction

or even an obstacle in the context of market re-

forms—and among the population presented with

the impotence and malleability of representative in-

stitutions in the face of economic collapse. Lilia

Shevtsova describes post-Soviet Russia as “elective

monarchy”; others emphasize a gradual reversal of

democratic achievements since 1991, under Vladimir

Putin in particular. The judgement about the ulti-

mate significance of democratization on its own

terms will hinge upon the extent to which a new

wave of democratizers learns the accumulated ex-

perience and is able to benefit from this knowledge.

See also: COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE SOVIET UNION;

PERESTROIKA; GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH;

YELTSIN, BORIS NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brown, Archie. (1996). The Gorbachev Factor. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Chiesa, Giulietto, and Northrop, Douglas Taylor. (1993).

Transition to Democracy: Political Change in the Soviet

Union, 1987–1991. Hanover, NH: University Press of

New England.

Cohen, Stephen F., and vanden Heuvel, Katrina, eds.

(1989). Voices of Glasnost. New York: Norton.

Dunlop, John B. (1993). The Rise of Russia and the Fall

of the Soviet Empire. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Uni-

versity Press.

Hough, Jerry F. (1997). Democratization and Revolution

in the USSR, 1985–1991. Washington, DC: Brook-

ings Institution.

Kagarlitsky, Boris. (1994). Square Wheels: How Russian

Democracy Got Derailed. New York: Monthly Review

Press.

Reddaway, Peter, and Glinski, Dmitri. (2001). Tragedy of

Russia’s Reforms: Market Bolshevism against Democ-

racy. Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press.

Starr, S. Frederick. (1988). “Soviet Union: A Civil Soci-

ety.” Foreign Policy.

Steele, Jonathan. (1994). Eternal Russia: Yeltsin, Gor-

bachev, and the Mirage of Democracy. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Theen, Rolf H. W., ed. (1991). The U.S.S.R. First Congress

of People’s Deputies: Complete Documents and Records,

May 25, 1989–June 10, 1989. Vol. 1. New York, NY:

Paragon House.

Urban, Michael E. (1990). More Power to the Soviets: The

Democratic Revolution in the USSR. Aldershot, UK:

Edward Elgar.

D

MITRI

G

LINSKI

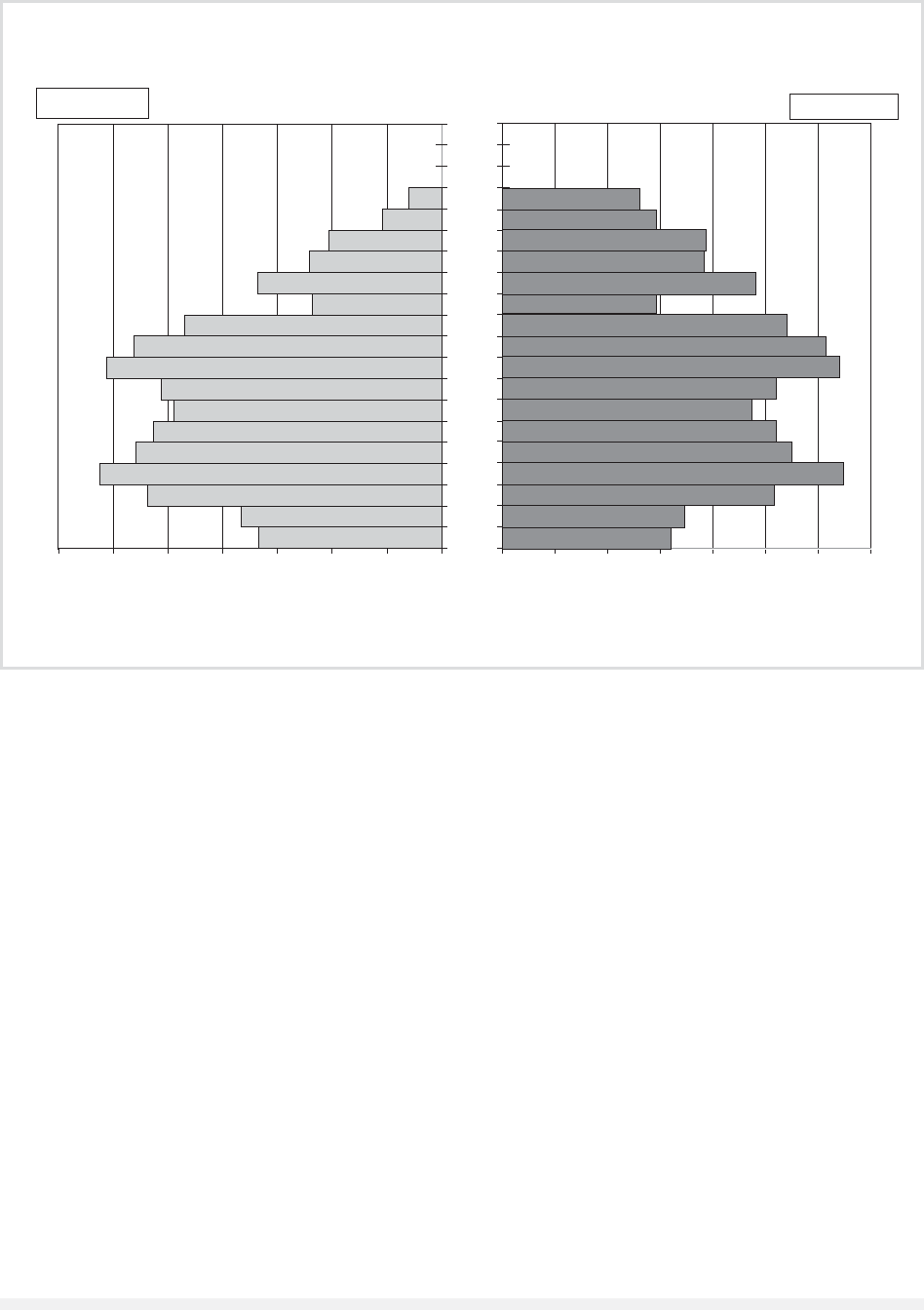

DEMOGRAPHY

The demography of Russia has influenced, and been

influenced by, historical events. Demographic shifts

can be seen in the population pyramid of 2002. The

imbalance at the top of the chart indicates many

more women live to older ages than men. The small

numbers aged 55-59 represents the drastic declines

in fertility from Soviet population catastrophes

during the 1930s and 1940s, followed by a post-

war baby boom aged 40-55. The relatively smaller

number of men and women aged 30-34 reflects the

echo of the 55–59 year old cohort. The larger co-

horts at younger ages reflect the echo effect of

Soviet baby boomers. The Russian population pyra-

mid is unique in its dramatic variation in cohort

DEMOGRAPHY

375

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

size, and illustrates how population has influenced,

and been influenced by, historical events.

Trends in migration, fertility, morbidity and

mortality shaped Russia’s growth rate, changed the

distribution of population resources, and altered the

ethnic and linguistic structure of the population. The

implications of demographic change varied by the

historical period in which it occurred, generated dif-

ferent effects between individuals of different age

groups, and influenced some birth cohorts more than

others. Throughout Russia’s history, demographic

trends were largely determined by global pandemics,

governmental policies and interventions, economic

development, public health practices, and severe pop-

ulation shocks associated with war and famine.

As in other countries, population trends pro-

vided a clear window into social stratification

within Russia, as improvements in public health

tended to be concentrated among elites, leaving the

poor more susceptible to illness, uncontrolled fer-

tility, and shorter life spans.

Two unique aspects concerning Russia’s de-

mographic history warrant note. During both the

Imperial and Soviet periods, demographic data were

manipulated to serve the ideological needs of the

state. Second, Russia’s demographic profile during

the 1990s raised questions concerning the perma-

nence of the epidemiological transition (of high

mortality and deaths by infectious disease to low

mortality and deaths by degenerative disease). Life

expectancies fell dramatically and infectious dis-

eases re-emerged during the 1990s as demographic

concerns became significant security issues.

SOURCES OF DEMOGRAPHIC DATA

The Mongols instituted the first population registry

in Russia, but few large-scale repositories of de-

mographic information existed before the late

Imperial period. Regional land registry (cadastral)

records provided household size information and

could be used with church records, tax assessment

documents, serf work assignments, and urban hos-

DEMOGRAPHY

376

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

SOURCE: U.S. Census International Database. <http://www.census.

g

ov/c

g

i-bin/ipc/idba

gg

>.

0

1,000,000

2,000,000

3,000,000

4,000,000

5,000,000

6,000,000

7,000,000

0

1,000,000

2,000,000

3,000,000

4,000,000

5,000,000

6,000,000

7,000,000

0–4

10–14

20–24

30–34

40–44

50–54

60–64

70–74

80–84

90–94

Male

Female

Population by Age and Sex, Russia, 2002

Table 1

pital records to provide indirect and localized esti-

mates of population, and in some cases, family for-

mation, fertility, and mortality data. In 1718, the

focus of enumeration shifted to an enumeration of

individuals, with adjustments or revizy, conducted

for verification. The move to local self-government,

and the creation of zemstvos in 1864, also provided

a wealth of historical data, particularly regarding

the demographic situation within peasant house-

holds, but as previous sources, the data were lim-

ited to small scale regional indicators. In 1897,

across the entire Russian Empire a population cen-

sus with 100,000 enumerators collected informa-

tion from 127 million present (nalichnoye) and

permanent (postoyannoye) residents on residence,

social class, language (but not ethnicity), occupa-

tion, literacy, and religion. A second census was

planned but not executed due to the outbreak of

World War I.

Enumeration and registration of the population

was a serious concern in the Soviet period, and cen-

suses of the population supplied important verifi-

cation of residence, linguistic identity, and ethnic

composition. The first comprehensive census in

1926 enumerated 147 million residents of the So-

viet Union, 92.7 million of whom resided in the

RSFSR. The next full census of 1939 was not pub-

lished, due to political concerns. Subsequent post-

war censuses in the Soviet Union (1959, 1970,

1979, 1989) improved significantly upon previous

censuses in terms of quality of coverage. These data

provided information that could be evaluated with

increasingly comprehensive records on fertility,

mortality, migration, and public health indicators

collected through various state ministries at the all-

union and republic levels.

During the post-Soviet period, scholars agree

the quality of population information declined dur-

ing the early 1990s, as state ministries reorganized,

funding for statistical offices became erratic, and

decentralization increased burdens for record keep-

ing for individual oblasts. A micro census was car-

ried out in 1994 of a 5 percent population sample.

After false starts in 1999 and 2001 and heated

debates over questionnaire content, the first post-

Soviet census was conducted in October of 2002.

DEMOGRAPHIC TRENDS IN

THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE

During the Time of Troubles (1598–1613), Russia

experienced a sharp population decline due to de-

clines in mortality and fertility. During the 1600s

Russia’s population increased, but the rate and sta-

bility of the trend over the century is subject to de-

bate. During the following century substantial ef-

forts to address public health needs were made in

Russia’s urban areas. Catherine II (the Great) es-

tablished the first medical administration during

the later 1700s, leading to some of the earliest epi-

demiological records for Russia. During the nine-

teenth century, mortality rates across age groups

were higher than those found in Europe. Infant

mortality was problematically high, declining only

during the late 1800s due to increased public health

campaigns.

Social changes such as the reforms of the 1860s

served as catalysts for improved living standards,

particularly in rural areas. These in turn improved

the population’s health. At the same time increases

in literacy also improved health practices. Educa-

tion and improvements in literacy across the em-

pire led to linguistic Russification with members of

various ethnic groups identifying primarily with

Russian language. The positive influence of im-

proved social conditions on demographic trends

was checked by persistently unreliable food pro-

duction and distribution, leading to widespread

famines throughout the imperial period, but most

notably in 1890. At the century’s close, increased

population density, particularly in urban areas, and

extremely poor public works infrastructural pro-

vided an excellent breeding ground for deadly out-

breaks of infectious diseases such as influenza,

cholera, tuberculosis, and typhoid. Deaths from in-

fectious diseases were higher in Russia than Europe

during the early 1890s. Voluntary Public Health

Commissions operated in the last decades of impe-

rial rule. Lacking official state financial support, the

commissions were unable to improve the health of

the lower classes living in conditions conducive to

disease transmission.

The state monitored the collection and dissem-

ination of demographic information throughout

the Imperial period. Records indicate that urban

population counts, estimated deaths due to infec-

tious disease, and population declines related to

famines were, in some cases, corrected in three spe-

cific ways in order to minimize negative interpre-

tations of living conditions within Russia and to

avoid possible public unrest. First, information was

simply not collected or published. In the case of fer-

tility and mortality statistics this avenue was eas-

ily followed as most births and deaths took place

at home and were not always registered. Secondly,

selected information was published for small scale

populations who tended to exhibit better health and

DEMOGRAPHY

377

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

survival profiles than the population at large. Fo-

cusing upon epidemiological records from large

urban hospitals, imperial estimates tend to under-

count the health profiles among rural residents and

the very poor, which tend to be far worse than

those with access to formal urban care. Lastly,

records may have been generated, but not pub-

lished. This appears to be the case in several analy-

ses of the 1890 famine and cholera outbreaks in

southern Russian during the 1800s. Rather than

utilizing demographic information to assist the de-

velopment of informed social policy, scholars con-

clude that national demographic information was

often manipulated in order to achieve specific ide-

ological goals.

DEMOGRAPHIC TRENDS

DURING THE SOVIET ERA

The early years of Soviet rule were marked by wide-

spread popular unrest, food shortages, civil war,

and massive migration movements. The cata-

strophic effects of World War I, a global influenza

epidemic, political and economic upheavals, and a

civil war led to steep increases in mortality, declines

in fertility, and deteriorations in overall population

health. Between 1920 and 1922, famine combined

with cholera and typhus outbreaks evoked a severe

population crisis. As Soviet power solidified, sev-

eral policies were enacted in the public health area,

specifically in the realm of maternal and child

health. Though underfunded, in combination with

the expansion of primary medical care through

feldshers (basic medical personnel), these programs

were associated with declines in infant mortality,

increased medical access, and improved population

health into the 1930s.

During the late 1920s food instability reap-

peared in the Soviet Union, followed by a brutal

collectivization of agriculture during the early

1930s. Millions of citizens of the Soviet Union per-

ished in the collectivization drive and the famine

that followed. Additional population losses oc-

curred as a result of the Stalinist repression cam-

paigns, as mortality was extremely high among

the nearly fifteen million individuals sent to forced

labor camps during the 1930s, and among the nu-

merous ethnic groups subject to forced deportation

and resettlement. These population losses were ac-

celerated by massive civilian and military casual-

ties during World War II. While each of these events

is significant in its own right, in combination they

produced a catastrophic loss of population that

significantly influenced the age structure of the

Russian Federation for decades to come. The popu-

lation loss consisted of not only those who per-

ished, but also the precipitous declines in fertility

in the period, in spite of intense pro-natalist efforts.

The precise population loss associated with this se-

ries of events is a subject of intense and emotional

debate, with estimates of population loss ranging

from 12 to nearly 40 million. Even individuals sur-

viving this tumultuous period were affected. Those

in their infancy or early childhood during the pe-

riod exhibited compromised health throughout

their lives as a result of the severe deprivation of

the period. Even after the end of the war, economic

instability and intense shortages exacted a signifi-

cant toll on living standards, fertility, and health

during the 1950s.

The 1959 census documented increasing pop-

ulation growth, improvements in life expectancy,

and increases in fertility across Russia. Life ex-

pectancy increased to sixty-eight years by 1959,

twenty-six years longer than the life expectancy

reported in 1926 (forty-two). The total fertility rate

in 1956 stood at 2.63, a marked increase from the

1940s. Urbanization increased the proportion of

the population with access to modern water and

sewer systems, and formal medical care. The fol-

lowing decades were periods of economic stability,

improving living standards, expanded social ser-

vices, improved health and decreased infectious dis-

ease prevalence. While overall fertility rates

declined, population growth was positive and no-

ticeable improvements were reported for infant and

maternal mortality in Russia.

During the late socialist period, improvements

in population health stalled, as Russia entered a pe-

riod of economic and social stagnation. Increased

educational and employment opportunities for

women, combined with housing shortages and the

need for dual income earners in each family, drove

fertility below replacement levels by 1970. Life ex-

pectancy, which peaked in 1961 at 63.78 for men

and 72.35 for women, declined during the 1970s

for both sexes. Negative health behaviors such as

smoking and drinking appeared to rise throughout

the 1970s and early 1980s, and some reports of

outbreaks of cholera and typhus were reported, es-

pecially in the southern and eastern regions of the

country. Official statistics indicate an improvement

in all demographic indicators in the mid-1980s, and

links to pro-family policies and a strict anti-alco-

hol campaign could be drawn, but improved mor-

tality and increased fertility were short-lived. By

DEMOGRAPHY

378

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the late 1980s increased mortality among males of

working age was observed.

The Soviet state also manipulated demographic

data to serve ideological ends. At best, official pub-

lications regarding issues such as life expectancy

were often overly optimistic. At worst, the compi-

lation of standard indicators (such as infant mor-

tality rates) was altered to improve the relative

standing of the Soviet Union in comparison to cap-

italist countries. Most significantly, demographic

information was withheld from publication, and

sometimes not collected. In spite of achieving re-

markable improvements in public health and high

rates of population growth in decades after World

War II, as its predecessor, employed population in-

formation to further its ideology as well as to in-

form policy development.

DEMOGRAPHIC TRENDS DURING

THE POST-SOVIET ERA

The post-Soviet era is marked by dire demographic

trends. Rapid and wide scale increases in mortality

and marked declines in already low fertility and

marriage rates generated negative natural rates of

increase throughout the 1990s. Population decline

was avoided only due to substantial immigration

from other successor states during the period. This

period has been identified as the most dramatic

peacetime demographic collapse ever observed. As-

pects of the crisis are linked to long-term processes

begun in the Soviet period, but were significantly

exacerbated by economic and institutional instabil-

ity of the later period.

Increasing male mortality, especially among

older working-aged males, gained momentum dur-

ing the 1990s. Estimates vary, but official estimates

reported a six-year decline in male life expectancy

between 1985 and 1995. Female life expectancy

also declined, however more modestly. Deaths from

lung cancer, accidents, suicide, poisoning, and other

causes related to alcohol consumption underpin the

change in mortality, but death rates for heart dis-

ease and cancer also increased. Period explanations

focus on the stress generated by the economic tran-

sition, linking that stress to the mortality increase.

Age effect models argue that men at these ages are

somehow uniquely susceptible to stress. Cohort ex-

planations point out that men in the later work-

ing ages (50–59) in 1990 represent the birth cohorts

of 1940s, and the declining mortality of the 1990s

is an echo of the deprivations of the post World

War II period. Each explanation contributed to ex-

plaining the mortality increase, which took place

amidst health care and infrastructural collapse.

The Soviet system of health care was very suc-

cessful in improving public health during the early

years of the regime, and during the initial period

after World War II, however the distribution and

organization of care led to diminishing return in

the later years of the regime and the organizational

structure proved ineffective in the post-Soviet pe-

riod. During the 1990s financial crises lead to se-

rious shortages of medical supplies, wage arrears

in the governmental health sector, and the rise of

private pay clinics and pharmacies. Increased

poverty rates, especially among the growing pen-

sion aged population, precluded health care access.

Public works (hospitals, prisons, sewer systems,

etc.) were poorly maintained during the late Soviet

era, and contributed to the resurgence of old health

risks such as cholera, typhus, and drug resistant

forms of tuberculosis during the 1990s. The

reemergence of infectious disease shocked demog-

raphers and epidemiologists, who previously con-

tended improvements in mortality were permanent,

and that deaths infectious diseases were a unique

characteristic of undeveloped societies. The resur-

gence of infectious diseases includes HIV/AIDS. The

numbers of infected were low, but in 2003 HIV in-

fection rates were projected to increase in the near

future.

Russia’s post-Soviet demographic crises gener-

ated concerns over declining population size, espe-

cially in the Far East where border security is a

concern. Immigration helped maintain population

size without shifting the ethnic composition, but

anti-immigrant sentiments were strong during the

late 1990s. In 2002 government attention had

turned to below replacement fertility, but as in the

rest of Europe the fertility rate remained very low.

During the second decade after Soviet rule, demo-

graphic trends were cause for serious concern, but

indicators, if not political attitudes, were stabilized.

See also: COLONIAL EXPANSION; COLONIALISM; EMPIRE,

USSR AS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, Barbara, and Silver, Brian. (1985). “Demo-

graphic Analysis and Population Catastrophes in the

USSR.” Slavic Review 44(3):517–536.

Applebaum, Anne. (2003). Gulag: A History. New York:

Doubleday.

DEMOGRAPHY

379

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Blum, Alain, and Troitskaya, Irina. (1997). “Mortality

in Russia During the 18th and 19th Century: Local

Assessments Based on the Revizii.” Population: An

English Selection 9:123–146.

Clem, Ralph. (1986). Research Guide to the Russian and

Soviet Censuses. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Coale, Ansley; Anderson, Barbara; and Harm, Erna.

(1979). Human Fertility in Russia since the Nineteenth

Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

DaVanzo, Julie, and Grammich, Clifford. (2002). Dire De-

mographics: Population Trends in the Russian Federa-

tion. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation.

Field, Mark. (1995). “The Health Crisis in the Soviet

Union: A Report form the ‘Post-War’ Zone.” Social

Science and Medicine 41(11):1469–1478.

Feshbach, Murray. (1995). Ecological Disaster: Cleaning

up the Hidden Legacy of the Soviet Regime. Washing-

ton, DC: Brookings Institute.

Hochs, Steven. (1994). “On Good Numbers and Bad:

Malthus, Population Trends and Peasant Standard of

Living in Late Imperial Russia.” Slavic Review 53(1):

41–75.

Kingkade, Ward. (1997). Population Trends: Russia.

Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census.

Lorimer, Frank. (1946). Population of the Soviet Union:

History and Prospects. Pompano Beach, FL: AMS Pub-

lishing.

Lutz, Wolfgang; Scherbov, Sergei; and Volkov, Andrei.

(1994). Demographic Trends and Patterns in the Soviet

Union before 1991. New York: Routledge.

Patterson, K. David. (1995). “Mortality in Late Tsarist

Russia: A Reconnaissance.” Social History of Medicine

8(2):179–210.

Wheatcroft, Stephen. (2000). “The Scale and the Nature

of the Stalinist Repression and Its Demographic Sig-

nificance: On Comments by Keep and Conquest.” Eu-

rope-Asia Studies 52(6):1143–1159.

C

YNTHIA

J. B

UCKLEY

DENGA

Throughout its history, the denga was a small sil-

ver coin, usually irregular in shape, with a fluctu-

ating silver content, weighing from 0.53 to 1.3

grams (depending on region and period). The word

denga was a lexicological borrowing into Russian

from Mongol. The unit’s origins are traced to

Moscow where, beginning in the 1360s and 1370s,

for the first time since the eleventh century, Rus

princes began to strike coins. By early 1400s, dengi

(pl.) were minted in other eastern Rus lands (Nizhe-

gorod and Ryazan) and by the 1420s in Tver, Nov-

gorod, and Pskov. Thereafter, dengi were minted

throughout the Rus lands by various independent

princes and differed in weight. However, unifor-

mity in weight, according to Moscow’s standards,

was introduced to the various principalities as the

Muscovite grand princes absorbed them during the

course of the second half of the fifteenth century.

For most of its history, six dengi made up an

altyn, and two hundred dengi the Muscovite ruble.

Novgorod also struck local dengi from the 1420s

until the last decades of the fifteenth century, but

their weight and value were twice the amount of

the dengi minted in Moscow. While the unit denga

was discontinued and replaced by the kopek with

the monetary reforms of Peter the Great, the Russ-

ian word dengi came to designate money in gen-

eral.

See also: ALTYN; COPPER RIOTS; GRIVNA; KOPECK; RUBLE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Noonan, Thomas S. (1997). “Forging a National Iden-

tity: Monetary Politics during the Reign of Vasilii I

(1389–1425).” In Moskovskaya Rus (1359–1584):

Kul’tura i istoricheskoe samosoznanie/Culture and

Identity in Muscovy, 1359–1584, ed. A. M. Kleimola

and G. D. Lenhoff. Moscow: ITZ-Garant.

Spasskii, I. G. (1967). The Russian Monetary System: A His-

torico-Numismatic Survey, tr. Z. I. Gorishina and rev.

L. S. Forrer. Amsterdam: Jacques Schulman.

R

OMAN

K. K

OVALEV

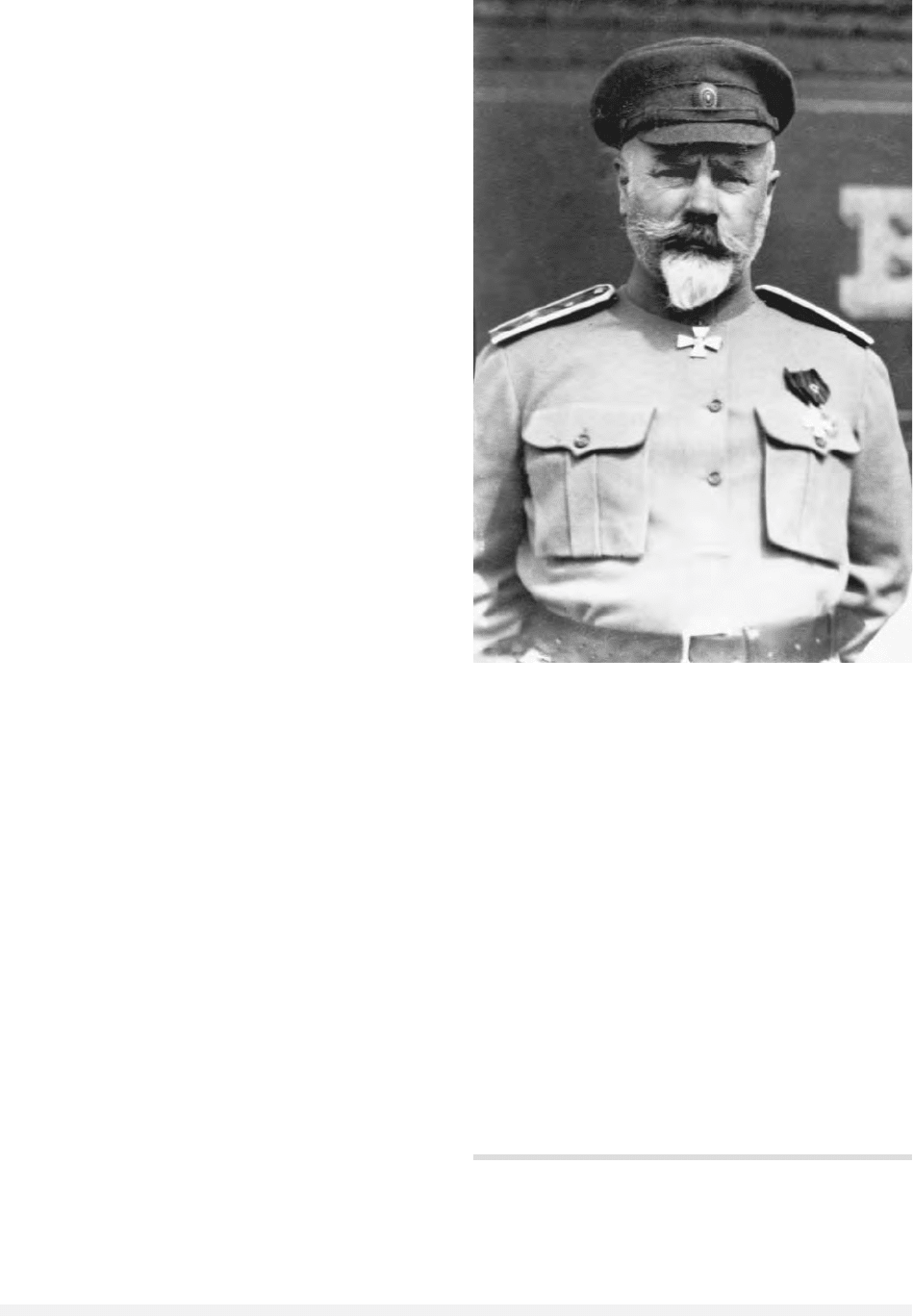

DENIKIN, ANTON IVANOVICH

(1872–1947), general, commander of White armies

in Southern Russia during the Russian civil war.

Anton Denikin was born the son of a retired

border guard officer in Poland. His own military

career began in the artillery, from which he en-

tered the General Staff Academy. He served in the

Russo-Japanese War and the World War I, where

he commanded the Fourth, or “Iron,” Brigade (later

a division). Beginning the war with the rank of

major general, following the February 1917 Rev-

olution, he received a rapid series of promotions,

from command of the Eighth Corps to command

of the Russian Western, and then Southwestern,

DENGA

380

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Fronts. In September 1917, however, he and a

number of other officers were arrested as associ-

ates of Commander-in-Chief General Lavr Kornilov

in the latter’s conflict with Prime Minister Alexan-

der Kerensky. Denikin was released from prison

following the Bolshevik coup. He headed to Novo-

cherkassk, where he participated in the formation

of the Anti-Bolshevik (White) Army together with

Kornilov and General Mikhail Alexeyev. Following

the death of Kornilov in April 1918, Denikin took

command of the White Army, which he led out

of its critical situation in the Kuban Cossack terri-

tory. General Alexeyev’s death in September of that

year left him with responsibility for civil affairs in

the White regions as well. With the subordination

to him of the Don and Kuban Cossack armies,

Denikin assumed the title Commander-in-Chief

of the Armed Forces of South Russia (December

1918).

By early 1919, the White Army controlled a

territory encompassing the Don and Kuban Cos-

sack territories and the North Caucasus. During the

spring and summer, the army advanced in all di-

rections, clearing the Crimea, taking Kharkov on

June 11 and Tsaritsyn (now Volgograd) on June

17. On June 20, 1919, Denikin issued the Moscow

Directive, an order which began the army’s offen-

sive on Moscow. After taking Kiev on August 17,

Kursk on September 7, and Orel (some two hun-

dred miles south of Moscow) on September 30, the

overextended White Army had reached the limits

of its advance. A Bolshevik counteroffensive initi-

ated a retreat that ultimately resulted in the army’s

evacuation of all its territory with the exception of

Crimea. This retreat was accompanied by epidemics

of typhus and other diseases, which decimated the

ranks of soldiers and the civilian population alike.

Denikin handed over command to General Pyotr

Wrangel on March 22, 1920, and left Russia for

Constantinople (Istanbul), and then France, where

he lived until November 1945. His final year and

nine months were spent in the United States. He

died on August 7, 1947, in Michigan.

The ill-fated Moscow offensive has colored

Denikin’s reputation, with some, such as General

Wrangel, arguing that the directive initiating it was

the death knell of the White movement in South

Russia. Wrangel advocated a junction with Admi-

ral Kolchak’s forces in the east. Denikin himself felt

that the conditions of the civil war were such that

only a risky headlong rush could unseat the Bol-

sheviks and put an end to the struggle.

See also: CIVIL WAR OF 1917–1922; WHITE ARMY;

WRANGEL, PETER NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Denikin, Anton I. (1922). The Russian Turmoil: Memoirs,

Military, Social, and Political. London: Hutchinson.

Denikin, Anton I. (1975). The Career of a Tsarist Officer:

Memoirs, 1872–1916. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press.

Lehovich, Dimitry V. (1974). White Against Red: The Life

of General Anton Denikin. New York: Norton.

A

NATOL

S

HMELEV

DENMARK, RELATIONS WITH

The earliest evidence of Danish-Russian interaction

consists of discoveries in Russia of tenth-century

DENMARK, RELATIONS WITH

381

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

General Anton Denikin, commander of the White Army. ©

CORBIS

Danish coins and an eleventh-century chronicle ref-

erence to trips by Danish merchants to Novgorod.

There are further mentions of Russian vessels to

Denmark in the twelfth century. However, the

available data is extremely fragmentary, and we

have no indication of any direct commerce in the

thirteenth through fifteenth centuries.

Danish-Muscovite political relations were first

established under a 1493 treaty between King Hans

and Ivan III, designed as an offensive agreement

against Sweden and Lithuania. The temporary

Danish takeover of Sweden in 1497 made the

Finnish border a source of contention, yet closer

ties were pursued through discussions about a dy-

nastic marriage. Frequent Danish embassies were

sent to Russia in the early years of the sixteenth

century, at which time Danish merchants also be-

gan to visit the Neva estuary and Ivangorod. A

Russian embassy attended the coronation of Chris-

tian II in 1514 and negotiated a new treaty, again

for the purpose of bringing about a Russian attack

on Sweden.

Relations began to deteriorate in the second half

of the sixteenth century due to Danish interest in

Livonia during the Livonian War and intensifying

border disputes between northern Norway and

Russia. However, the Moscow treaty of 1562 rec-

ognized the Danish acquisition of the island of

Ösel/Saaremaa off the Estonian coast in 1559. In

1569 Duke Magnus was made the administrator

of Russian Livonia and married with Ivan IV’s

niece, although the couple subsequently was forced

to flee to Poland. Further problems were created by

Danish efforts to control and tax Western Euro-

pean shipping with Russia’s Arctic Sea coast.

Nonetheless, Boris Godunov in 1602 proposed a

marriage between his daughter and the Danish

Prince Hans who, however, died in Moscow soon

after his arrival.

Danish economic interests in northern Russia

increased after the establishment of the Romanov

regime, and shipping on a fairly modest scale was

almost annual. A diplomatic crisis ensued from

Christian IV’s ultimately unsuccessful efforts to set

up a special company for illegal direct trade with

the fur-rich areas to the east of Arkhangelsk. The

Danish navy even raided Kola in 1623. The Danes

further rejected overtures for a dynastic marriage

in the early 1620s. Relations soon warmed again

during Danish involvement in the Thirty Years’

War, and the Muscovite government provided

grain as a subsidy from 1627 to 1633.

The most serious effort at linking the Danish

and Russian ruling families came between 1643 and

1645 when Prince Valdemar Christian was to be

married with Tsarevna Irina Mikhailovna. How-

ever, differences over relations with Sweden and the

refusal of Valdemar to convert to Orthodox ulti-

mately scuttled the project. Attempts to contain

Sweden again led to a rapprochement in the 1650s.

The same considerations prompted Denmark to join

Peter’s anti-Swedish alliance to participate—with

limited success—in the Great Northern War in

1700. Peter I visited Denmark in 1716 for discus-

sions about a planned reconquest of southern Swe-

den. Relations deteriorated when the plans remained

on paper and the Danes rejected a royal marriage

proposal.

The Russian marriage-based alliance in 1721

with the ducal house of Gottorp—an independent-

minded Danish vassal—evolved into a lasting

source of tension between the two countries, espe-

cially under the long reign of Elizabeth Petrovna,

who appointed the Gottorpian future Peter III as

her successor. Open warfare between the two coun-

tries was only averted by Catherine II’s coup d’état.

During her reign, Denmark became a key link in

Nikita Panin’s Northern system. An alliance was

established in 1773, and the end of the century saw

a sharp increase in Danish-Russian commerce,

making Russia one of Denmark’s leading trade

partners. Tsar Pavel’s desire to seek Swedish sup-

port against England constituted the main threat

to this alliance.

Denmark reacted to the rise of Napoleon by

adopting a neutral position and refused to join in

offensive action in northern Germany, fearing the

safety of its possessions. Russia diplomatically sup-

ported Denmark against English aggression, but

Swedish willingness to support Russia in return for

the annexation of Norway from Denmark led to a

cooling of Danish-Russian relations. Denmark was

eventually forced to join the anti-French coalition

and to accept the loss of Norway in 1814. Russian

efforts to compensate Denmark ultimately resulted

only in the acquisition of the small northern Ger-

man city of Lauenburg.

Political relations in the nineteenth century

were to a significant degree driven by a Russian de-

sire to ensure free access to the Baltic through the

Danish Sound and to balance off Sweden and Den-

mark against each other. The rise of Scandinavism

was often associated with anti-Russian sentiment,

which the government sought to control. In 1849,

DENMARK, RELATIONS WITH

382

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY