Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

seal) by the qarachi beys for them to go into effect.

Their witnessing was also required for all agree-

ments with foreign powers to become official. The

khan was not allowed to meet with foreign am-

bassadors without the presence of the qarachi beys,

as representatives of the major chiefdoms. At times

an assembly called a quriltai advised the khan but

could also be called to choose a new khan or de-

pose the reigning khan. Notable men from the rul-

ing class made up the quriltai, and this included

the khan’s relatives and retinue, religious leaders,

and other members of the nobility from the ruling

class’s lower ranks. The government was set up on

a dual-administrative basis with a vizier in charge

of civilian administration, including record-keeping

and the treasury. The beklaribek (head of the qarachi

beys) presided over military administration. The

clan of each qarachi bey held the highest social and

political status within its chiefdom, with people of

every social status in descending order down to

slaves beneath.

Six of the early khans of the Qipchaq Khanate

were sky worshipers, the traditional religion of the

Mongols. One of these khans, Sartaq (r. 1256–1257),

may have been a Nestorian Christian and another,

Berke (r. 1257–1267), was Muslim. But all the

early khans followed policies of religious toleration.

In the early fourteenth century, Khan Özbek (r.

1313–1341) converted to Islam, which from then

on became the official religion of the elite of the

Khanate and spread to most of the rest of the pop-

ulation. The Rus principalities, however, remained

Christian, since the Rus Church enjoyed the protec-

tion of the khans as long as the Rus clergy prayed

for the well-being of the khan and his family.

The Qipchaq Khanate had extensive diplomatic

dealings with foreign powers, both as part of the

Mongol Empire and independently. It maintained

agreements with the Byzantine Empire and Mam-

luk Egypt. It fought incessantly with the Ilkhanate

and maintained alternating periods of agreement

and conflict with the Grand Dukes of Lithuania. It

maintained extensive commercial dealings with

Byzantium, Egypt, Genoa, Pisa, and Venice to the

west, as well as with the other Mongol khanates

and China to the east. During the fourteenth cen-

tury, a high Islamic Turkic culture emerged in the

Qipchaq Khanate.

At the end of the thirteenth century, the

Qipchaq Khanate survived a devastating civil war

between Khan Tokhta and the Prince Nogai. After

the assassination of Khan Berdibek in 1359, the

khanate went through more than 20 years of tur-

moil and endured another devastating civil war,

this time between Khan Tokhtamish and the Emir

Mamai. In 1395 Tamerlane swept through the

khanate, defeated the army of Tokhtamish, and

razed the capital cities. In the middle of the fif-

teenth century the Qipchaq Khanate began to split

up, with the Crimean Khanate and Kazan Khanate

separating off. Finally in 1502, the Crimean Khan

Mengli Girey defeated the last khan of the Qipchaq

Khanate, absorbed the western part of the khanate

into his domains, and allowed the organization of

the Khanate of Astrakhan to govern the rest. The

Qipchaq Khanate, nonetheless, had lasted far

longer as an independent political entity than any

of the other ulus granted by Chinghis Khan to his

sons.

See also: ASTRAKHAN, KHANATE OF; BATU; CENTRAL ASIA;

CRIMEAN KHANATE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fedorov-Davydov, G. A. (1984). The Culture of the Golden

Horde Cities, tr. H. Bartlett Wells. Oxford: B.A.R.

Fedorov-Davydov, G. A. (2001). The Silk Road and the

Cities of the Golden Horde. Berkeley, CA: Zinat Press.

Halperin, Charles J. (1985). Russia and the Golden Horde:

Mongol Impact on Medieval Russian History. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

Schamiloglu, Uli. (1986). “Tribal Politics and Social Or-

ganization in the Golden Horde.” Ph.D. diss., Co-

lumbia University, New York.

Schamiloglu, Uli. (2002). “The Golden Horde.” In The

Turks, 6 vols., ed. Hasan Celâl Güzel, C. Cem Oguz,

and Osman Karatay, 2:819–835. Ankara: Yeni

Türkiye.

Vernadsky, George. (1953). The Mongols and Russia. New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

D

ONALD

O

STROWSKI

GOLD STANDARD

A gold standard is a monetary system in which a

country backs its currency with gold reserves and

allows the conversion of its currency into gold.

Tsarist Russia introduced the gold standard in Jan-

uary 1897 and maintained it until 1914. The pol-

icy was adopted both as a means of attracting

foreign capital for the ambitious industrialization

efforts of the late tsarist era, and to earn interna-

tional respectability for the regime at a time when

the world’s leading economies had themselves

GOLD STANDARD

573

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

adopted gold standards. Preparation for this move

began under Russian Finance Minister Ivan Vysh-

negradsky (1887–1892), who actively built up

Russia’s gold supply while restricting the supply of

paper money. After a brief setback, the next finance

minister, Sergei Witte (1892–1903), continued to

amass gold reserves and restrict monetary growth

through foreign borrowing and taxation. By 1896,

Russian gold reserves had reached levels commen-

surate (in relative terms) with other major Euro-

pean nations on the gold standard. The gold

standard proved so controversial in Russia that it

had to be introduced directly by imperial decree,

over the objections of the State Council (Duma).

This decree was promulgated on January 2, 1897,

authorizing the emission of new five- and ten-

ruble gold coins. At this point the state bank (Gos-

bank) became the official bank of issue, and Rus-

sia pegged the new ruble to a fixed quantity of gold

with full convertibility. This meant that the ruble

could be exchanged at a stable, fixed rate with the

other major gold-backed currencies of the time,

which facilitated trade by eliminating foreign ex-

change risk.

Private foreign capital inflows increased con-

siderably after the introduction of the gold stan-

dard, and currency stability increased as well. By

World War I, Russia had been transformed from a

state set somewhat apart from the international fi-

nancial system to the world’s largest international

debtor. Proponents argue that the gold standard ac-

celerated Russian industrialization and integration

with the world economy by preventing inflation

and attracting private capital (substituting for the

low rate of domestic savings). They also point out

that the Russian economy might not have recov-

ered so quickly after the Russo-Japanese war and

civil unrest in 1904 and 1905 without the promise

of stability engendered by the gold standard. Crit-

ics, however, charge that the gold standard required

excessively high foreign borrowing and tax, tariff,

and interest rates to introduce. They further charge

that once in place, the gold standard was defla-

tionary, inflexible, and too preferential to foreign

investment. Economist Paul Gregory argues that

the entire debate may be moot, inasmuch as Rus-

sia had no choice but to adopt the gold standard in

an international environment that practically re-

quired it for countries wishing to take advantage

of the era’s large-scale cross-border trade and in-

vestment opportunities. Russia abandoned the gold

standard in 1914 under the financial pressure of

World War I.

See also: FOREIGN TRADE; INDUSTRIALIZATION; VYSHNE-

GRADSKY, IVAN ALEXEYEVICH; WITTE, SERGEI YULIE-

VICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Drummond, Ian. (1976). “The Russian Gold Standard,

1897–1914.” Journal of Economic History 36(4):

633–688.

Gerschenkron, Alexander. (1962). Economic Backwardness

in Historical Perspective: A Book of Essays. Cambridge,

MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Gregory, Paul. (1994). Before Command: An Economic His-

tory of Russia from Emancipation to the First Five-Year

Plan. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Von Laue, Theodore. (1963). Sergei Witte and the Indus-

trialization of Russia. New York: Columbia Univer-

sity Press.

J

ULIET

J

OHNSON

GOLITSYN, VASILY VASILIEVICH

(1643–1714), chief minister and army commander

during the regency of Sophia Alekseyevna.

Prince Vasily Golitsyn was the eldest son of

Prince Vasily Andreyevich Golitsyn and Tatiana

Streshneva. Both his parents were from aristocratic

clans with strong connections, which brought

young Vasily the honorific posts of cup-bearer to

Tsar Alexis in 1658 and coach attendant in 1666.

In 1663 he married Avdotia Streshneva, who bore

him six children. In 1675 he was posted to Ukraine,

where he served intermittently during the Russo-

Turkish war of 1676–1681, leading an auxiliary

force, organizing fortification works and provi-

sioning, and taking a major role in negotiations

with Cossack leaders. He was appointed comman-

der in chief of the southern army just before the

truce of 1681. During visits to court, Golitsyn won

the favor of Tsar Fedor (r. 1676–1682), who pro-

moted him to the rank of boyar in 1676. He also

held posts as director of the Artillery Chancellery

and the Vladimir High Court. In 1681 he returned

to Moscow to chair a commission on army reform,

with special reference to regimental structure and

the appointment of officers. The commission’s pro-

posals led to the abolition in January 1682 of the

Code of Precedence, although its scheme for provin-

cial vice-regencies was rejected.

Following Tsar Fedor’s death in May 1682,

Golitsyn rose further thanks to the patronage of

GOLITSYN, VASILY VASILIEVICH

574

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Tsarevna Sophia Alekseyevna, who became regent

to the joint tsars Ivan V (r. 1682–1696) and Peter

I (r. 1682–1725). Their relationship is said to have

begun when Sophia was caring for the ailing Fe-

dor, to whose bedchamber Golitsyn often reported,

but contemporary Russian sources do not record

any such meetings. The claim that the couple be-

came lovers rests on hearsay and some coded let-

ters dating from the later 1680s. Golitsyn was not

closely involved in the intrigues with the Moscow

militia (musketeers) that brought Sophia to power

following a bloody revolt, but he remained close to

the tsars during the so-called Khovanshchina and

was appointed director of the important Foreign

Office, and later accumulated the directorships of

the Foreign Mercenaries, Cavalry, Little Russian

(Ukrainian), Smolensk, Novgorod, Ustyug, and

Galich chancelleries, which afforded him a sub-

stantial power base. In 1683 Sophia dubbed him

“Guardian of the Tsar’s Great Seal and the State’s

Great Ambassadorial Affairs.”

Golitsyn’s main talent was for foreign affairs.

He was unusual among Russian boyars in know-

ing Latin and Greek and became known as a friend

of foreigners. He was instrumental in negotiating

the renewal of the 1661 Treaty of Kardis with Swe-

den (1684), trade treaties with Prussia (1689), and

the important treaty of permanent peace with

Poland (1686), by which Russia broke its truce with

the Ottomans and Tatars and entered the Holy

League against the infidels. In fulfillment of Rus-

sia’s obligations to the League, Golitsyn twice led

vast Russian armies to Crimea, in 1687 and 1689,

on both occasions returning empty-handed, hav-

ing suffered heavy losses as a result of shortages

of food and water. Golitsyn’s enemies blamed him

personally for the defeats, but Sophia greeted him

as a victor, thereby antagonizing the party of the

second tsar Peter I, who objected to “undeserved re-

wards and honors.” Following a stand-off between

the two sides in August–September 1689, Golitsyn

was arrested for aiding and abetting Sophia, by-

passing the tsars, and causing “losses to the sover-

eigns and ruin to the state” as a result of the

Crimean campaigns. He and his family were exiled

to the far north, first to Kargopol, then to Archangel

province, where he died in 1714.

Historians have characterized Golitsyn as a

“Westernizer,” one of a select band of educated and

open-minded Muscovite boyars. His modern views

were reflected not only in his encouragement of

contacts with foreigners, but also in his library of

books in foreign languages and his Moscow man-

sion in the fashionable “Moscow Baroque” style,

which was equipped with foreign furniture, clocks,

mirrors, and a portrait gallery, which included

Golitsyn’s own portrait. The French traveler Foy de

la Neuville (the only source) even credited Golitsyn

with a scheme for limiting, if not abolishing, serf-

dom, which is not, however, reflected in the legis-

lation of the regency. Golitsyn’s downfall was

brought about by a mixture of bad luck and poor

judgement in court politics. Peter I never forgave

him for his association with Sophia and thereby

forfeited the skills of one of the most able men of

his generation.

See also: FYODOR ALEXEYEVICH; SOPHIA ALEXEYEVNA

(TSAREVNA); WESTERNIZERS.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hughes, Lindsey. (1982). “A Seventeenth-century West-

erniser: Prince V.V. Golitsyn (1643–1714).” Irish

Slavonic Studies 3:47–58.

Hughes, Lindsey. (1984). Russia and the West: The Life of

a Seventeenth-Century Westernizer, Prince Vasily

Vasil’evich Golitsyn (1643–1714). Newtonville, MA:

Oriental Research Partners.

Smith, Abby. (1995). “The Brilliant Career of Prince

Golitsyn.” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 19:639–645.

L

INDSEY

H

UGHES

GONCHAROVA, NATALIA SERGEYEVNA

(1881–1962), artist, book illustrator, set and cos-

tume designer.

Natalia Sergeyevna Goncharova was born on

June 21, 1881, in the village of Nagaevo in the

Tula province; she died on October 17, 1962, in

Paris. She lived in Moscow from 1892 and enrolled

at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and

Architecture in 1901 to study sculpture. She met

Mikhail Larionov in 1900–1901 who encouraged

her to paint and became her lifelong companion.

They were married in 1957. In 1906 she con-

tributed to the Russian Section at the Salon d’Au-

tomne, Paris. In 1908–1910 she contributed to

the three exhibitions organized by Nikolai Ri-

abushinsky, editor of the journal Zolotoe runo (The

Golden Fleece) in Moscow. In 1910 she founded

with Larionov and others the Jack of Diamonds

group and participated in their first exhibition. In

1911 the group split and from 1911–1914 she par-

ticipated in a series of rival exhibitions organized

GONCHAROVA, NATALIA SERGEYEVNA

575

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

by Larionov: the “Donkey’s Tail” (1912), the “Tar-

get “(1913), and the “No. 4” (1914). Throughout

this period she worked in several styles— Primi-

tivist, Cubist, and, in 1912–1913, Futurist and

Rayist. Her work immediately became a lightning

rod for debate over the legitimacy and cultural

identity of new Russian painting. In 1910 a one-

day exhibition of Goncharova’s work was held at

the Society for Free Esthetics. The nude life studies

she displayed on this occasion led to her trial for

pornography in Moscow’s civil court (she was ac-

quitted). Major retrospective exhibitions of Gon-

charova’s work were organized in Moscow (1913)

and St. Petersburg (1914). Paintings of religious

subject matter were censored, and in the last exhi-

bition temporarily banned as blasphemous by the

Spiritual-Censorship Committee of the Holy Synod.

On April 29, 1914 Goncharova left with

Larionov for Paris to mount Sergei Diagilev’s pro-

duction of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Le Coq d’Or (a col-

laboration between herself and choreographer

Mikhail Fokine). Also in 1914, the Galerie Paul

Guillaume in Paris held her first commercial exhi-

bition. During the 1920s and 1930s she and Lari-

onov collaborated on numerous designs for Diagilev

and other impresarios. Returning briefly to Mos-

cow in 1915, she designed Alexander Tairov’s pro-

duction of Carlo Goldoni’s Il Ventaglio at the

Chamber Theater, Moscow. After traveling with

Diagilev’s company to Spain and Italy, she settled

in Paris with Larionov in 1917. In 1920–1921 she

contributed to the “Exposition internationale d’art

moderne” in Geneva and in 1922 exhibited at the

Kingore Gallery, New York. From the 1920s on-

ward she continued to paint, teach, illustrate books,

and design theater and ballet productions. After

1930, except for occasional contributions to exhi-

bitions, Larionov and Goncharova lived unrecog-

nized and impoverished. Through the efforts of

Mary Chamot, author of Goncharova’s first major

biography, a number of their works entered mu-

seum collections, including the Tate Gallery, London,

the National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, and

the National Art Gallery in Wellington, New Zealand.

In 1954 their names were resurrected at Richard

Buckle’s “The Diagilev Exhibition” in Edinburgh

and London. In 1961 Art Council of Great Britain

organized a major retrospective of Goncharova’s

and Larionov’s works, and numerous smaller ex-

hibitions were held throughout Europe during the

1970s. In 1995 the Musée national d’art moderne,

Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris organized a large

exhibition of their work in Europe. Exhibitions

were also held at the State Tretyakov Gallery,

Moscow (1999, 2000). The first retrospective of her

Russian oeuvre since 1914 was held at the State

Russian Museum in St. Petersburg in 2002.

See also: DIAGILEV, SERGEI PAVLOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Artcyclopedia Web site. (2003) <www.artcyclopedia

.com/artists/goncharova_natalia.html>.

Chamot, Mary. (1972). Gontcharova Paris: La Biblio-

theque des Arts.

Lukanova, Alla and Avtonomova, Natalia, eds. (2000).

Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova. Exhibition Cat-

alogue. Moscow: State Tretiakov Gallery.

Petrova, Evgeniia, ed. (2002). Natalia Goncharova: the

Russian Years. Exhibition Catalogue. St. Petersburg:

The State Russian Museum and Palace Editions.

J

ANE

A. S

HARP

GONCHAROV, IVAN ALEXANDROVICH

(1812–1891), writer.

Born in Simbirsk to a family of wealthy mer-

chants, Ivan Goncharov moved to Moscow for his

schooling in 1822 and then moved to St. Peters-

burg in 1835 where, with a few breaks, he re-

mained until his death. He worked from 1855 to

1867 as government censor, a post that earned the

criticism and mistrust of many of his contempo-

raries. Although his politics as a censor were clearly

conservative when it came to reviewing Russian

journals, he also used his position to allow many

important and liberal works of literature into print,

including works by Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Alex-

ander Herzen. Goncharov’s unfounded accusation

of plagiarism against the novelist Ivan Turgenev

in 1860 caused a scandal in the literary world;

Goncharov suffered from bouts of neurosis and

paranoia and lived most of his life in sedentary

seclusion.

Goncharov is known primarily for three novels—

A Common Story (1847), Oblomov (1859), and The

Precipice (1869)—as well as a travel memoir of a

government expedition to Japan, The Frigate Pal-

las (1855–1857). By far his best-known work is

Oblomov, whose hero, an indolent and dreamy

Russian nobleman, became emblematic of a Russ-

ian social type, the superfluous man. The figure

of Oblomov made such a deep impression on read-

ers that the radical critic Nikolai Dobrolyubov pop-

GONCHAROV, IVAN ALEXANDROVICH

576

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ularized the term oblomovshchina (oblomovitis) to

describe the ineptitude of the Russian intelligentsia.

Goncharov’s novels rank him among the best Rus-

sian realist writers, yet his university years in

Moscow at the height of the Russian romantic

movement and his consequent attraction to its

ideals places him within the era of the Golden Age

of Russian literature.

See also: GOLDEN AGE OF RUSSIAN LITERATURE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ehre, Milton. (1974). Oblomov and His Creator; the Life

and Art of Ivan Goncharov. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press.

Lyngstad, Alexandra, and Lyngstad, Sverre. (1971). Ivan

Goncharov. New York: Twayne Publishers.

Setchkarev, Vsevolod. (1974). Ivan Goncharov: His Life

and Works. Wurzburg: Jal-Verlag.

C

ATHERINE

O’N

EIL

GOODS FAMINE

The concept of the goods famine refers to excess

demand (at prevailing prices) for industrial goods

in the Soviet Union during the latter half of the

1920s. The importance of this excess demand can

only be understood within the context of the New

Economic Policy (NEP) of the 1920s and the un-

derlying forces leading to excess demand. Specifi-

cally, the goods famine was an outgrowth of the

Scissors Crisis and state policies relating to this

episode.

Specifically, in the middle and late 1920s, the

quicker recovery of agricultural production relative

to industrial production meant that increases in the

demand for industrial goods could not be met, an

outcome characterized as the goods famine. State

policy was ultimately successful in forcing a re-

duction of the prices of industrial goods. The con-

cern was that a goods famine might drive rural

producers, unable to purchase industrial goods, to

reduce their grain marketings. This was viewed as

a critical factor limiting the possible pace of indus-

trialization.

The goods famine is important to the under-

standing of the changes implemented by Stalin in

the late 1920s. Moreover, these events relate to eco-

nomic issues such as the nature and organization

of the industrial sector (e.g., monopoly power), state

policies in a semi-market economy, and most im-

portant, the nature of peasant responses to market

forces when facing the imperatives of an industri-

alization drive.

See also: AGRICULTURE; ECONOMIC GROWTH, SOVIET; IN-

DUSTRIALIZATION, SOVIET; NEW ECONOMIC POLICY;

PEASANT ECONOMY; SCISSORS CRISIS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gregory, Paul R. (1994). Before Command: An Economic

History of Russia from Emancipation to the First Five

Year Plan. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Zaleski, Eugene. (1971). Planning for Economic Growth in

the Soviet Union, 1918–1932. Chapel Hill: University

of North Carolina Press.

R

OBERT

C. S

TUART

GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH

(b. 1931), Soviet political leader, general editor of

the CPSU (1985–1991), president of the Soviet

Union (1990–1991), Nobel Peace Prize laureate

(1990).

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev, the leader of

the Soviet Union during a period of sweeping do-

mestic and international change that saw the

dismantling of communist systems throughout

Europe and ended with the disintegration of the

USSR itself, was born in the southern Russian vil-

lage of Privolnoye in Stavropol province. His par-

ents were peasants and his mother was barely

literate.

Mikhail Gorbachev did not have an easy child-

hood. Born on March 2, 1931, he was just old

enough to remember when, during the 1930s, both

of his grandfathers were caught in the purges and

arrested. Although they were released after prison,

having been tortured in one case and internally ex-

iled and used as forced labor in the other, young

Misha Gorbachev knew what it was like to live in

the home of an enemy of the people.

The war and early postwar years provided the

family with the opportunity to recover from the

stigma of false charges laid against the older gen-

eration, although the wartime experience itself was

harsh. Gorbachev’s father was in the army, saw

action on several fronts, and was twice wounded.

Remaining in the Russian countryside, Gorbachev

and his mother had to engage in back-breaking

GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH

577

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

work in the fields. For two years Gorbachev re-

ceived no schooling, and for a period of four and

one-half months the Stavropol territory, including

Privolnoye, was occupied by the German army. In

Josef Stalin’s time, those who had experienced even

short-lived foreign rule tended to be treated with

grave suspicion.

Nevertheless, the Gorbachevs engaged as whole-

heartedly in the postwar reconstruction of their lo-

cality as they had in the war effort. Exceptionally,

when he was still a teenager, Gorbachev was

awarded the Order of Red Banner of Labor for heroic

feats of work. He had assisted his father, a com-

bine operator (who was given the Order of Lenin)

in bringing in a record harvest in 1948. The odds

against a village boy gaining entry to Moscow State

University in 1950 were high, but the fact that

Gorbachev had been honored as an exemplary

worker, and had an excellent school record and rec-

ommendation from the Komsomol, made him one

of the exceptions. While still at high school during

the first half of 1950, Gorbachev became a candi-

date member of the Communist Party. He was ad-

mitted to full membership in the party in 1952.

Although the Law Faculty of Moscow Univer-

sity, where Gorbachev studied for the next five

years, hardly offered a liberal education, there were

some scholars of genuine erudition who opened his

eyes to a wider intellectual world. Prominent

among them was Stepan Fyodorovich Kechekyan,

who taught the history of legal and political

thought. Gorbachev took Marxism seriously and

not simply as Marxist-Leninist formula to be

learned by rote. Talking, forty years later, about

his years as a law student, Gorbachev observed:

“Before the university I was trapped in my belief

system in the sense that I accepted a great deal as

given, assumptions not to be questioned. At the

university I began to think and reflect and to look

at things differently. But of course that was only

the beginning of a long process.”

Two events of decisive importance for Gor-

bachev occurred while he was at Moscow Univer-

sity. One was the death of Stalin in 1953. After

that the atmosphere within the university light-

ened, and freer discussion began to take place

among the students. The other was his meeting

Raisa Maximovna Titarenko, a student in the phi-

losophy faculty, in 1951. They were married in

1953 and remained utterly devoted to each other.

In an interview on the eve of his seventieth birth-

day, Gorbachev described Raisa’s death at the age

of 67 in 1999 as his “hardest blow ever.” They had

one daughter, Irina, and two granddaughters.

After graduating with distinction, Gorbachev

returned to his native Stavropol and began a rapid

rise through the Komsomol and party organiza-

tion. By 1966 he was party first secretary for

Stavropol city, and in 1970 he became kraikom first

secretary, that is, party boss of the whole Stavropol

territory, which brought with it a year later mem-

bership in the Central Committee of the CPSU. Gor-

bachev displayed a talent for winning the good

opinion of very diverse people. These included not

only men of somewhat different outlooks within

the Soviet Communist Party. Later they were also

to embrace Western conservatives—most notably

U.S. president Ronald Reagan and U.K. prime min-

ister Margaret Thatcher—as well as European so-

cial democrats such as the former West German

chancellor Willy Brandt and Spanish Prime Minis-

ter Felipe Gonzalez.

However, Gorbachev’s early success in winning

friends and influencing people depended not only

on his ability and charm. He had an advantage in

his location. Stavropol was spa territory, and lead-

ing members of the Politburo came there on holi-

day. The local party secretary had to meet them,

and this gave Gorbachev the chance to make a good

impression on figures such as Mikhail Suslov and

Yuri Andropov. Both of them later supported his

promotion to the secretaryship of the Central Com-

mittee, with responsibility for agriculture, when

one of Gorbachev’s mentors, Fyodor Kulakov, a

previous first secretary of Stavropol territory, who

held the agricultural portfolio within the Central

Committee Secretariat (along with membership in

the Politburo), died in 1978.

From that time, Gorbachev was based in Mos-

cow. As the youngest member of an increasingly

geriatric political leadership, he was given rapid

promotion through the highest echelons of the

Communist Party, adding to his secretaryship can-

didate membership of the Politburo in 1979 and

full membership in 1980. When Leonid Brezhnev

died in November 1982, Gorbachev’s duties in the

Party leadership team were extended by Brezhnev’s

successor, Yuri Andropov, who thought highly of

the younger man. When Andropov was too ill to

carry on chairing meetings, he wrote an adden-

dum to a speech to a session of the Central Com-

mittee in December 1983, which he was too ill to

attend in person. In it he proposed that the Polit-

buro and Secretariat be led in his absence by Gor-

GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH

578

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

bachev. This was a clear attempt to elevate Gor-

bachev above Konstantin Chernenko, a much older

man who had been exceptionally close to Brezhnev

and a senior secretary of the Central Committee for

longer than Gorbachev. However, Andropov’s ad-

ditions to his speech were omitted from the text

presented to Central Committee members. Cher-

nenko had consulted other members of the old

guard, and they were united in wishing to prevent

power from moving to a new generation repre-

sented by Gorbachev.

The delay in his elevation to the general secre-

taryship of the Communist Party did Gorbachev no

harm. Chernenko duly succeeded Andropov on the

latter’s death in February 1984, but was so infirm

during his time at the helm that Gorbachev fre-

quently found himself chairing meetings of the

Politburo at short notice when Chernenko was too

ill to attend. More importantly, the sight of a third

infirm leader in a row (for Brezhnev in his last years

had also been incapable of working a full day)

meant that even the normally docile Central Com-

mittee might have objected if the Politburo had pro-

posed another septuagenarian to succeed Chernenko.

By the time of Chernenko’s death, just thirteen

months after he succeeded Andropov, Gorbachev

was, moreover, in a position to get his way. As the

senior surviving secretary, it was he who called the

Politburo together on the very evening that Cher-

nenko died. The next day (March 11, 1985) he was

unanimously elected Soviet leader by the Central

Committee, following a unanimous vote in the

Politburo.

Those who chose him had little or no idea that

they were electing a serious reformer. Indeed, Gor-

bachev himself did not know how fast and how

radically his views would evolve. From the outset

of his leadership he was convinced of the need for

change, involving economic reform, political liber-

alization, ending the war in Afghanistan, and im-

proving East-West relations. He did not yet believe

that this required a fundamental transformation of

the system. On the contrary, he thought it could

be improved. By 1988, as Gorbachev encountered

increasing resistance from conservative elements

within the Communist Party, the ministries, the

army, and the KGB, he had reached the conclusion

that systemic change was required.

Initially, Gorbachev had made a series of per-

sonnel changes that he hoped would make a differ-

ence. Some of these appointments were bold and

innovative, others turned out to be misjudged. One

of his earliest appointments that took most ob-

servers by surprise was the replacement of the long-

serving Soviet foreign minister, Andrei Gromyko,

by the Georgian Party first secretary, Eduard She-

vardnadze, a man who had not previously set foot

in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Yet Shevardnadze

became an imaginative and capable executor of a

foreign policy aimed at ending the Cold War. At

least as important a promotion was that given to

Alexander Yakovlev, who was not even a candidate

member of the Central Committee at the time when

Gorbachev became party leader, but who by the

summer of 1987 was both a secretary of the Cen-

tral Committee and a full member of the Politburo.

Yakovlev owed this extraordinarily speedy promo-

tion entirely to the backing of Gorbachev. He, in

turn, was to be an influential figure on the reformist

wing of the Politburo during the second half of the

1980s.

Other appointments were less successful. Yegor

Ligachev, a secretary of the Central Committee who

had backed Gorbachev strongly for the leadership,

was rapidly elevated to full membership in the

GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH

579

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

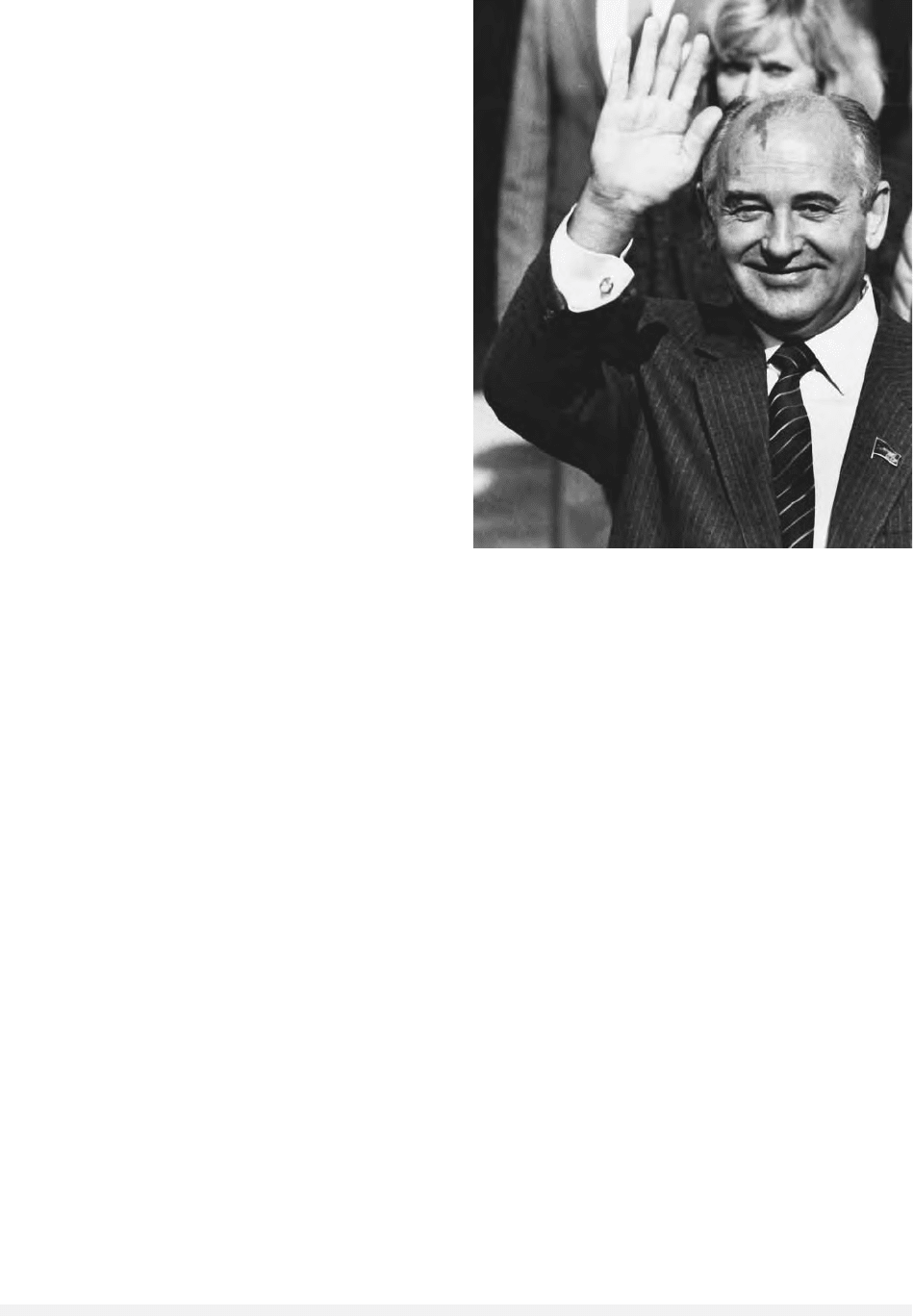

General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev waves to the crowd at

Orly Airport in Paris. R

EUTERS

/B

ETTMANN

. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

Politburo and for a time was de facto second sec-

retary within the leadership. But as early as 1986

it was clear that his reformism was within very

strict limits. Already he was objecting to intellec-

tuals reexamining the Soviet past and taking ad-

vantage of the new policy of glasnost (openness or

transparency) that Gorbachev had enunciated. Suc-

cessive heads of the KGB and of the Ministry of De-

fense were still more conservative than Ligachev,

and the technocrat, Nikolai Ryzhkov, as chairman

of the Council of Ministers, was reluctant to aban-

don the economic planning system in which, as a

factory manager and, subsequently, state official,

he had made his career.

Gorbachev embraced the concept of demokrati-

zatsiya (democratization) from the beginning of his

General Secretaryship, although the term he used

most often was perestroika (reconstruction). Ini-

tially, the first of these terms was not intended to

be an endorsement of pluralist democracy, but sig-

nified rather a liberalization of the system, while

perestroika was a useful synonym for reform, since

the very term reform had been taboo in Soviet pol-

itics for many years. Between 1985 and 1988,

however, the scope of these concepts broadened.

democratization began to be linked to contested

elections. Some local elections with more than one

candidate had already taken place before Gorbachev

persuaded the Nineteenth Party Conference of the

Communist Party during the summer of 1988 to

accept competitive elections for a new legislature,

the Congress of People’s Deputies, to be set up the

following year. That decision, which filled many

of the regional party officials with well-founded

foreboding, was to make the Soviet system differ-

ent. Even though the elections were not multiparty

(the first multiparty elections were in 1993), the

electoral campaigns were in many regions and cities

keenly contested. It became plain just how wide a

spectrum of political views lay behind the mono-

lithic facade the Communist Party had tradition-

ally projected to the outside world and to Soviet

citizens.

While glasnost had brought into the open a

constituency favorably disposed to such reforms,

no such radical departure from Soviet democratic

centralism could have occurred without the strong

backing of Gorbachev. Up until the last two years

of the existence of the Soviet Union the hierarchi-

cal nature of the system worked to Gorbachev’s ad-

vantage, even when he was pursuing policies that

were undermining the party hierarchy and, in that

sense, his own power base. While there had been a

great deal of socioeconomic change during the

decades that separated Stalin’s death from Gor-

bachev’s coming to power, there was one impor-

tant institutional continuity that, paradoxically,

facilitated reforms that went beyond the wildest

dreams of Soviet dissidents and surpassed the

worst nightmares of the KGB. That was the power

and authority of the general secretaryship of the

Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party,

the post Gorbachev held from March 1985 until

the dissolution of the CPSU in August 1991 and

which—in particular, for the first four of his six

and one-half years at the top of the Soviet politi-

cal system—made him the principal policy maker

within the country. Perestroika, which had origi-

nally meant economic restructuring and limited

reform, came to stand for transformative change

of the Soviet system. Both the ambiguity of the

concept and traditional party norms kept many

officials from revolting openly against perestroika

until it was too late to close the floodgates of

change.

A major impetus to Gorbachev’s initial reforms

had been the long-term decline in the rate of eco-

nomic growth. Indeed, the closest thing to a con-

sensus in the Soviet Union in 1985–1986 was the

need to get the country moving again economi-

cally. A number of economic reforms introduced

by Gorbachev and Ryzhkov succeeded in breaking

down the excessive centralization that had been a

problem of the unreformed Soviet economic sys-

tem. For example, the Law on the State Enterprise

of 1987 strengthened the authority of factory

managers at the expense of economic ministries,

but it did nothing to raise the quantity or quality

of production. The Enterprise Law fostered infla-

tion, promoted inter-enterprise debt, and facilitated

failure to pay taxes to the central budget.

The central budget also suffered severely from

one of the earliest policy initiatives supported by

Gorbachev and urged upon him by Ligachev. This

was the anti-alcohol campaign, which went beyond

exhortation and involved concrete measures to limit

the production, sale, and distribution of alcohol. By

1988 this policy was being relaxed. In the mean-

time, it had some measure of success in cutting

down the consumption of alcohol. Alcohol-related

accidents declined, and some health problems were

alleviated. Economically, however, the policy was

extremely damaging. The huge profits on which the

state had relied from the sale of alcohol, on which

it had a monopoly, were cut drastically not only

because of a fall in consumption but also because,

GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH

580

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

under conditions of semi-prohibition, moonshine

took the place of state-manufactured vodka. Since

the launch of perestroika had also coincided with a

drop in the world oil price, this was a loss of rev-

enue the state and its political leadership could not

afford.

Gorbachev had, early in his general secretary-

ship, been ready to contemplate market elements

within the Soviet economy. By 1989–1990 he had

increasingly come to believe that market forces

should be the main engine of growth. Nevertheless,

he favored what he first called a “socialist market

economy” and later a “regulated market.” He was

criticized by market fundamentalists for using the

latter term, which they saw as an oxymoron. Al-

though by 1993 Yegor Gaidar, a firm supporter of

the market, was observing that “throughout the

world the market is regulated.” Gorbachev initially

endorsed, and then retreated from, a radical but (as

its proponents were later to admit) unrealistic pol-

icy of moving the Soviet Union to a market econ-

omy within five hundred days. The Five-Hundred-

Day Plan was drawn up by a group of economists,

chosen in equal numbers by Gorbachev and Boris

Yeltsin (the latter by this time a major player in

Soviet and Russian politics), during the summer of

1990. In setting up the working group, in consul-

tation with Yeltsin, Gorbachev completely bypassed

the Communist Party. He had been elected presi-

dent of the Soviet Union by the Congress of Peo-

ple’s Deputies of the USSR in March 1990 and was

increasingly relying on his authority in that role.

However, the presidency did not have the institu-

tional underpinning that the party apparatus had

provided for a General Secretary—until Gorbachev

consciously loosened the rungs of the ladder on

which he had climbed to the top. Ultimately, in the

face of strong opposition from state and party au-

thorities attempting to move to the market in a gi-

ant leap, Gorbachev sought a compromise between

the views of the market enthusiasts, led by Stani-

slav Shatalin and Grigory Yavlinsky, and those of

the chairman of the Council of Ministers and his

principal economic adviser, Leonid Abalkin.

Because radical democrats tended also to be in

favor of speedy marketization, Gorbachev’s hesita-

tion meant that he lost support in that con-

stituency. People who had seen Gorbachev as the

embodiment and driving force of change in and of

the Soviet system increasingly in 1990–1991 trans-

ferred their support to Yeltsin, who in June 1991

was elected president of Russia in a convincing first-

round victory. Since he had been directly elected,

and Gorbachev indirectly, this gave Yeltsin a greater

democratic legitimacy in the eyes of a majority of

citizens, even though the very fact that contested

elections had been introduced into the Soviet sys-

tem was Gorbachev’s doing. If Gorbachev had taken

the risk of calling a general election for the presi-

dency of the Soviet Union a year earlier, rather than

taking the safer route of election by the existing

legislature, he might have enhanced his popular le-

gitimacy, extended his own period in office, and ex-

tended the life of the Soviet Union (although, to

the extent that it was democratic, it would have

been a smaller union, with the Baltic states as the

prime candidates for early exit). In March 1990,

the point at which he became Soviet president, Gor-

bachev was still ahead of Yeltsin in the opinion

polls of the most reliable of survey research insti-

tutes, the All-Union (subsequently All-Russian)

Center for the Study of Public Opinion. It was dur-

ing the early summer of that year that Yeltsin

moved ahead of him.

By positing the interests of Russia against those

of the Union, Yeltsin played a major role in mak-

ing the continuation of a smaller Soviet Union an

impossibility. By first liberalizing and then democ-

ratizing, Gorbachev had taken the lid off the na-

tionalities problem. Almost every nation in the

country had a long list of grievances and, when

East European countries achieved full independence

during the course of 1989, this emboldened a num-

ber of the Soviet nationalities to demand no less.

Gorbachev, by this time, was committed to turn-

ing the Soviet system into something different—

indeed, he was well advanced in the task of dis-

mantling the traditional Soviet edifice—but he

strove to keep together a multinational union by

attempting to turn a pseudo-federal system into a

genuine federation or, as a last resort, a looser con-

federation.

Gorbachev’s major failures were unable to

prevent disintegration of the union and not im-

proving economic performance. However, since

everything was interconnected in the Soviet Union,

it was impossible to introduce political change

without raising national consciousness and, in

some cases, separatist aspirations. If the disinte-

gration of the Soviet Union is compared with the

breakup of Yugoslavia, what is remarkable is the

extent to which the Soviet state gave way to fif-

teen successor states with very little bloodshed. It

was also impossible to move smoothly from an

economic system based over many decades on one

set of principles (a centralized, command economy)

GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH

581

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

to a system based on another set of principles (mar-

ket relations) without going through a period of

disruption in which things were liable to get worse

before they got better.

Gorbachev’s failures were more than counter-

balanced by his achievements. He changed Soviet

foreign policy dramatically, reaching important

arms control agreements with U.S. president Rea-

gan and establishing good relations with all the

Soviet Union’s neighbors. Defense policy was sub-

ordinated to political objectives, and the underly-

ing philosophy of kto kogo (who will defeat whom)

gave way to a belief in interdependence and mu-

tual security. These achievements were widely rec-

ognized internationally—most notably with the

award to Gorbachev in 1990 of the Nobel Peace

Prize. If Gorbachev is faulted in Russia today, it is

for being overly idealistic in the conduct of foreign

relations, to an extent not fully reciprocated by his

Western interlocutors. The Cold War had begun

with the Soviet takeover of Eastern Europe. It ended

when one East and Central European country af-

ter another became independent in 1989 and when

Gorbachev accepted the loss of Eastern Europe,

something all his predecessors had regarded as non-

negotiable. Gorbachev’s answer to the charge from

domestic hard-liners that he had “surrendered”

Eastern Europe was to say: “What did I surrender,

and to whom? Poland to the Poles, the Czech lands

to the Czechs, Hungary to the Hungarians....”

After the failed coup against Gorbachev of Au-

gust 1991, when he was held under house arrest

on the Crimean coast while Yeltsin became the

focal point of resistance to the putschists, his

political position was greatly weakened. With the

hard-liners discredited, disaffected nationalities

pressed for full independence, and Yeltsin became

increasingly intransigent in pressing Russian inter-

ests at the expense of any kind of federal union. In

December 1991 the leaders of the Russian, Ukrain-

ian, and Belorussian republics got together to an-

nounce that the Soviet Union was ceasing to exist.

Gorbachev bowed to the inevitable and on Decem-

ber 25 resigned from the presidency of a state, the

USSR, which then disappeared from the map.

During the post-Soviet period Gorbachev held

no position of power, but he continued to be po-

litically active. His relations with Yeltsin were so

bad that at one point Yeltsin attempted to prevent

him from travelling abroad, but abandoned that

policy following protests from Western leaders.

Throughout the Yeltsin years, Gorbachev was

never invited to the Kremlin, although he was con-

sulted on a number of occasions by Vladimir Putin

when he succeeded Yeltsin. Gorbachev’s main ac-

tivities were centered on the foundation he headed,

an independent think-tank of social-democratic

leanings, which promoted research, seminars, and

conferences on developments within the former So-

viet Union and on major international issues. Gor-

bachev became the author of several books, most

notably two volumes of memoirs published in

Russian in 1995 and, in somewhat abbreviated

form, in English and other languages in 1996.

Other significant works included a book of politi-

cal reflections, based on tape-recorded conversa-

tions with his Czech friend from university days,

Zdene

k Mlynár

, which appeared in 2002. He

became active also on environmental matters as

president of the Green Cross International. Domes-

tically, Gorbachev lent his name and energy to an

attempt to launch a Social Democratic Party, but

with little success. He continued to be admired

abroad and gave speeches in many different coun-

tries. Indeed, the Gorbachev Foundation depended

almost entirely on its income from its president’s

lecture fees and book royalties.

Gorbachev will, however, be remembered above

all for his contribution to six years that changed

the world, during which he was the last leader of

the USSR. Notwithstanding numerous unintended

consequences of perestroika, of which the most re-

grettable in Gorbachev’s eyes, was the breakup of

the Union, the long-term changes for the better in-

troduced in the Gorbachev era—and to a significant

degree instigated by him—greatly outweigh the

failures. Ultimately, Gorbachev’s place in history is

likely to rest upon his playing the most decisive

role in ending the Cold War and on his massive

contribution to the blossoming of freedom, in East-

ern Europe and Russia itself.

See also: AUGUST 1991 PUTSCH; DEMOCRATIZATION;

GLASNOST; GORBACHEV, RAISA MAXIMOVNA; NEW

POLITICAL THINKING; PERESTROIKA; YELTSIN, BORIS

NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Braithwaite, Rodric. (2002). Across the Moscow River: The

World Turned Upside Down. New Haven, CT: Yale

University Press.

Breslauer, George. (2002). Gorbachev and Yeltsin as Lead-

ers. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, Archie. (1996). The Gorbachev Factor. Oxford: Ox-

ford University Press.

GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH

582

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY