Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

assembled in an Editorial Commission. They had

enormous energy and guile. They managed to con-

vince Alexander that their critics were actually chal-

lenging his autocratic prerogatives.

The legislative process was epitomized when

the commission’s draft came before the Council of

State in early 1861. The council was composed of

Alexander’s friends and confidants. It voted down

each section of the draft by large margins. The

members were counting on the emperor’s sympa-

thy and his distrust of reformers. These dignitaries

could not, however, come up with a coherent al-

ternative. Furthermore, the council was not a leg-

islature. With each section of the draft, the emperor

used his prerogative to endorse the minority posi-

tion, and the Editorial Commission’s version be-

came law without significant change. The result

was a cautious reform that was nonetheless much

more radical than anyone in authority had con-

templated.

The terms of the legislation promulgated on

February 19, 1861, varied from province to prov-

ince. The reformers wanted to accommodate the

nobility. Hence, in the North the allotments of

land assigned to the ex-serfs were relatively large

but costly; since the land was of little value, the

squires would rather have cash. To the south,

where land was valuable, the allotments were

smaller but not so costly. The complexity of the

legislation is compounded by special cases, some

involving millions of peasants. The commune was

unknown in Ukraine and was not imposed there.

State peasants would be more generously treated

than serfs when the reform was extended to them

in 1866; the regime was more willing to sacrifice

its interests than those of serfholders. If one fo-

cuses on a majority of Great Russian serfs, one

can grasp the reform by comparing it to the sys-

tem of serfdom.

(1) Authority: The essence of serfdom was the

subjection of the serfs to the arbitrary power of

their master or mistress. Serfholders could buy and

sell serfs and subject them to physical or sexual

abuse. The laws limiting the squires’ powers were

vague and rarely enforced. This arbitrary power of

the serfholding noble was utterly abolished by the

legislation of 1861. The ex-serfs found themselves

subject in a new way, however, to the nobles as a

class, because they dominated local administration.

And most ex-serfs were dependent, as renters,

wage-laborers, or sharecroppers, on a squire in the

neighborhood.

(2) Ascription: A second element of serfdom

was ascription, or fastening. The reform left peas-

ants ascribed, but transferred the power to regu-

late their comings and goings from the squire to

the village commune, which now issued the pass-

ports that enabled peasants to go in search of wage

work. The government retained ascription as a se-

curity measure.

(3) Economics: It was the economic elements of

the reform that most severely restricted the free-

dom of ex-serfs. Most peasants received (through

the commune) an allotment of land and had to meet

the obligations that went with the allotment. It was

almost impossible to dispose of the allotment. Few

peasants who wanted to pull up stakes and start

afresh could do so.

Servile agriculture was linked to the reparti-

tional commune. Plowland was held by the com-

mune and subject to periodic repartition among

households. The objective of repartition was to

match landholding to the labor-power of each

household, since the commune allocated and real-

located burdens, such as taxes, as well as plowland.

The reform, like the serfholders before, imposed a

system of mutual responsibility. If one household

did not meet its obligations, the others had to make

up the difference. It was in the interests of the com-

mune that each household have plowland propor-

tional to its labor power.

Also characteristic of the servile economy was

“extraeconomic compulsion.” Under serfdom, it

was not the market but the serfholders’s arbitrary

authority that determined the size of the serfs’ al-

lotments and the dues they had to render. After the

reform, these were determined not by the market,

but by law.

These characteristics of the servile economy

broke down slowly because, to minimize disrup-

tion, the reformers took the elements of serfdom as

their point of departure. The size of the allotments

set by statute derived from the size under serfdom.

In the interests of security, the reformers retained

the commune, although it impeded agricultural

progress. The statutes sought to minimize the eco-

nomic dependence of ex-serfs on their former mas-

ters. They provided that peasants could redeem their

allotments over a forty-nine-year period. Redemp-

tion entailed an agreement between the squire and

his ex-serfs, which was hard to achieve. Until the

redemption process began in a village, the ex-serfs

were in a state of “temporary obligation,” subject

to yesterday’s serfholder. Within limits set by

GREAT REFORMS

603

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

statute, they had to render dues in cash or in labor

in return for their allotments.

The abolition of serfdom regulated more than

it changed, but regulation represented an enormous

change: The arbitrary power of the serfholder had

been the essence of serfdom. The reform could not

provide an immediate stimulus to economic devel-

opment. The regime set a higher value on stabil-

ity, on the prosperity of the nobility, and on the

welfare of the peasantry, than on development. It

feared chaos more than it wanted progress. So it

imposed stability and opened the way for a slow

passage out of the structures of serfdom.

It is argued that the other great reforms fol-

lowed from the abolition of serfdom, but the peas-

ant reform reordered the Russian village, while the

other reforms addressed the opposite end of the so-

cial spectrum. For example, the education reform

(1863) restored autonomy to Russia’s universities,

permitting the rector and faculty to run them; the

minister of education, however, had broad author-

ity to interfere. It also provided for technical sec-

ondary schools. However, only graduates of the

traditional, classical schools could enter the uni-

versities; the regime supposed that Greek and Latin

had a sobering effect on the young. The reform also

gave new authority, but little money, to local agen-

cies to establish primary schools. Finally, it allowed

some education to women, provided that they

would get an education “appropriate for the future

wife and mother.”

The censorship was reformed in 1865. Under

the old system, a censor went over every word of

a book or magazine, deleting or changing anything

subversive. This system had been supportive of

serfdom, but useful publications had been impeded,

and pre-censorship had not prevented the dissem-

ination of radical ideas. The emperor wanted

knowledge to flourish, but he was suspicious of

intellectuals. He observed, “There are tendencies

which do not accord with the views of the gov-

ernment; they must be stopped.” The censorship

reform did that. It eliminated the prepublication

censorship of books and most journals. Editors and

publishers were responsible for everything they

printed, however, and subject to heavy fines, crim-

inal penalties, and the closing of periodicals. The

regime appreciated that publishers dreaded finan-

cial loss. The result was self-censorship, more ex-

acting than precensorship.

The Judicial Reform (1864) was not closely re-

lated to the abolition of serfdom, since peasants

were not usually subject to the new courts. Under

the old system, justice had been a purely bureau-

cratic activity. There were no juries, no public tri-

als, and no legal profession. Corruption and delay

were notorious. Commercial loans were available

only on short terms and at high interest because

the courts could not protect the interests of credi-

tors.

The new system provided for independent

judges with life tenure; trial by jury in criminal

cases; oral and public trials; and an organized bar

of lawyers to staff this adversary system. Peasants

were formally eligible to serve on juries, but prop-

erty qualifications for jury service excluded all but

a few peasants. Here, as elsewhere, distinctions

linked to the system of estates of the realm (soslo-

viya) were retained by other means.

The reform of the courts had long been under

discussion. Officials who shared the emperor’s sus-

picion of lawyers and juries were unable to produce

any workable alternative to the chaos they knew.

Hence the task of drafting the new system passed

to a group of younger men with advanced legal

training. With the task came powers of decision

making. The reformers acted in the spirit of the cos-

mopolitan legal ethos they had acquired with their

training. They, alone of the drafters of reform

statutes, avowedly followed western models and

produced the most thorough-going of the reforms.

The zemstvo, or local government, reform

(1864) provided for elective assemblies at the dis-

trict and provincial levels; the electorate was divided

into three curias: landowners (mostly nobles),

peasant communities, and towns. Voting power

was proportional to the value of real estate held by

each curia, but no curia could have more than half

the members.

The zemstvo’s jurisdiction included the upkeep

of roads, fire insurance, education, and public

health. Squires and their ex-serfs sat together in the

assemblies, if not in proportion to their share of

the population. Public-spirited squires found a

sphere of activity in the boards elected by the as-

semblies. These boards, in turn, hired health work-

ers, teachers, and other professionals. The zemstvo

provided an arena of public service apart from the

state bureaucracy, where liberal landowners and

dissidents interacted. The accomplishments of the

zemstvo were remarkable, given their limited re-

sources and the government control over them. The

provincial governor could suspend any decision

taken by a zemstvo. The zemstvo had only a lim-

GREAT REFORMS

604

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ited power to tax, and as much as half the total it

collected went to functions performed for the state.

Why didn’t the government do more? It cher-

ished autocracy and realized that genuine consti-

tutional change would favor the rich and the

educated, not the peasants; many nobles sought a

national zemstvo as compensation for their sup-

posed losses. Most important, to let authority pass

to judges, juries, editors, and others not under di-

rect bureaucratic discipline required a trust in

which the regime was deficient. Many bureaucrats

feared that the reforms would come back to haunt

the regime. They were right. The bar did become a

rallying point for dissidents, the economic and so-

cial position of the nobility did decline, and the zem-

stvo eventually protested. Cautious officials can be

good prophets, even if the solutions they offer are

ineffective.

See also: ALEXANDER II; EMANCIPATION ACT; PEASANTRY;

SERFDOM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bushnell, John; Eklof, Ben; and Zakharova, Larisa, eds.

(1994). Russia’s Great Reforms. Bloomington: Indi-

ana University Press.

Field, Daniel. (1976). The End of Serfdom: Nobility and Bu-

reaucracy in Russia, 1855–1861. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Mironov, Boris. (1999). A Social History of Imperial Rus-

sia, 1700–1917, 2 vols., ed. Ben Eklof. Boulder, CO:

Westview.

Wortman, Richard. (1976). The Development of a Russian

Legal Consciousness. Chicago: University of Chicago

Press.

D

ANIEL

F

IELD

GREECE, RELATIONS WITH

Ideas originating in Greece, a country in south-

eastern Europe that occupies the southernmost part

of the Balkan Peninsula and is bordered by the

Aegean, Mediterranean, and Ionian seas, first in-

fluenced Russian culture as early as the tenth cen-

tury, during the golden age of Kievan Rus. Prince

Vladimir (978–1015) adopted Eastern Orthodoxy,

which reflected his close personal ties with Con-

stantinople, a city that dominated both the Black

Sea and the Dnieper River, Kiev’s busiest commer-

cial route. Adherence to the Eastern Orthodox

Church had long-range political, cultural, and re-

ligious consequences for Russia. The church liturgy

was written in Cyrillic, and a corpus of transla-

tions from the Greeks had been produced for the

South Slavs. The existence of this literature facili-

tated the East Slavs’ conversion to Christianity and

introduced them to rudimentary Greek philosophy,

science, and historiography without the necessity

of learning Greek. Russians began to look to the

Greeks for religious inspiration and came to regard

the Catholics of Central Europe as schismatics. This

tendency laid the foundation for Russia’s isolation

from the mainstream of Western civilization.

Seeking warm-water ports, Russian explorers

were attracted to Greece. No part of mainland

Greece is more than 100 kilometers (60 miles) from

water, and islands constitute about one-fifth of the

country’s land area. By the nineteenth century, as

the Russian Empire expanded to the southwest, its

population grew more diverse and began to include

Greek Orthodox peoples.

After Russia’s defeat by Japan in 1905, the gov-

ernment began to take a more active interest in the

Balkans and the Near East. The decline of the Ot-

toman Empire (“the sick man of Europe”) encour-

aged nationalist movements in Greece, Serbia,

Romania, and Bulgaria. In 1912 the Balkan League,

which included Greece, defeated the Ottoman Em-

pire in the First Balkan War. A year later, the al-

liance split, and the Greeks, Serbs, and Romanians

defeated Bulgaria in the Second Balkan War. Rus-

sia tried to extend its influence over the new na-

tions. Greco-Russian relations became strained

when Russia sided with Serbia in the conflict be-

tween Serbia and Greece for control of Albania.

Greece fought on the side of the Western allies

and Russia in World War I, and similarly on the

side of the Allies, including the Soviet Union, in

World War II. In the immediate aftermath of the

war, tensions arose between the legitimate Greek

government and the Soviet Union. The Greek re-

sistance movement during World War II, the Na-

tional Liberation Front (EAM) and its army (ELAS),

were dominated by the Communist Party. When

the Greek government-in-exile returned to Athens

in late 1944 shortly after the liberation, the com-

munists tried to overthrow it, and in the ensuring

civil war they were supported by Josef Stalin’s

USSR and (more enthusiastically) Tito’s Yugoslavia.

Britain funded the non-communists, but when the

economic commitment exceeded its postwar capa-

bilities, the United States took on the burden with

GREECE, RELATIONS WITH

605

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the Truman Doctrine. Thanks to massive military

and economic aid from the United States, which

came just in time, the communists, who had es-

tablished a provisional government in the northern

mountains, were ultimately defeated.

Relations between Greece and the USSR cooled

with the former’s admission to NATO in 1952. Be-

ginning in the mid-1950s, NATO’s southeastern

flank experienced periodic cycles of international

tension. The problem in Cyprus, where the popu-

lation is split between Greek-Cypriots (approxi-

mately 78%) and Turkish-Cypriots (18%) led

eventually to a Turkish invasion of the island on

July 20, 1974, to protect the Turkish-Cypriot mi-

nority.

Nevertheless, Greek-Soviet ties established dur-

ing the 1980s not only survived the political up-

heaval that ended the Soviet Union, they even

improved. In 1994 Greece signed new protocols

with Russia for delivery of natural gas from a

pipeline to run from Bulgaria to Greece. In 2002,

during its fourth presidency of the European Union

(EU), Greece repeatedly called for improved rela-

tions with Russia. At the Russia-EU summit in

Brussels on November 11, 2002, Prime Minister

Costas Simitis emphasized the importance of im-

plementing the Brussels agreement on the Kalin-

ingrad region, an enclave on the Baltic Sea that

would be cut off from the rest of Russia by the

Schengen zone when Poland and Lithuania joined

the EU. Greece also prepared a new strategy for

greater cooperation between Russia and the EU,

which is Russia’s largest trading partner.

See also: BALKAN WARS; KIEVAN RUS; ORTHODOXY;

ROUTE TO GREEKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gerolymatos, André. (2003). The Balkan Wars: Conquest,

Revolution, and Retribution from the Ottoman Era to

the Twentieth Century and Beyond. New York: Basic

Books.

Gvosdev, Nicholas. (2001). An Examination of Church-

State Relations in the Byzantine and Russian Empires

with an Emphasis on Ideology and Models of Interac-

tion. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press.

Joseph, Joseph S. (1999). Cyprus Ethnic Conflict and In-

ternational Politics: From Independence to the Thresh-

old of the European Union. New York: Palgrave

Macmillan.

Koliopoulos, John S. (1999). Plundered Loyalties: World

War II and Civil War in Greek West Macedonia. New

York: New York University Press.

Prousis, Theophilus. (1994). Russian Society and the Greek

Revolution. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University

Press.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

GREEKS

As early as 1000

B

.

C

.

E

., pre-Hellenic Greeks, in

search of iron and gold, explored the southeast

shores of the Black Sea. Beginning in the fifth and

sixth centuries

B

.

C

.

E

., Greeks established fishing vil-

lages at the mouths of the Danube, Dnieper, Dni-

ester, and Bug Rivers. They founded the colony of

Olbia between the eighth and sixth centuries

B

.

C

.

E

.

near the South Bug River and carried on trade in

metals, slaves, furs, and later grain. Greek jewelry,

coins, and wall paintings attest to the presence of

Greek colonies during the Scythian, Sarmatian, and

Roman domination of the area.

During the late tenth century

C

.

E

., Prince

Vladimir of Kievan Rus accepted the Orthodox

Christian religion after marrying Anna, sister of

Greek Byzantine Emperor Basil II. With the con-

version came the influence of Greek Byzantine

culture including the alphabet, Greek religious lit-

erature, architecture, icon painting, music, and

crafts. The East Slavs carried on a vigorous trade

with Byzantium following the famous route “from

the Varangians to the Greeks”—from the Baltic to

the Black Sea.

With the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in

1453, many Greeks, fleeing onerous taxes, emi-

grated to Russia. Ivan III (1462–1505) married

Sophia, the niece of the last Byzantine emperor, giv-

ing rise to the Muscovite claim that Moscow was

the “Third Rome.” Ivan, like many future Russian

rulers, employed Greeks as architects, painters,

diplomats, and administrators.

The opening of the Black Sea grain trade with

Western Europe and the Near East during the early

nineteenth century gave impetus to a large Greek

immigration to the Black Sea coast. Greek merchant

families prospered in Odessa, which was the head-

quarters of the Philiki Etaireia Society, advocating

the liberation of Greece from Turkey (1821–1829).

In 1924 some 70,000 Greeks left the Soviet

Union for Greece. Of the estimated 450,000 Greeks

at the time of Stalin, 50,000 Greeks perished dur-

ing the collectivization drive and Purges of the

GREEKS

606

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

1930s. Greeks, especially from the Krasnodar Re-

gion, were sent to the Solovki Gulag and to Siberia.

In 1938 all Greek schools, theaters, newspapers,

magazines, and churches were closed down. In

1944 Crimean and Kuban Greeks were exiled to

Kazakhstan. Between 1954 and 1956 Greek exiles

were released, but they could not return to the

Crimea until 1989. The last major immigration of

Greeks to the Soviet Union began in 1950 with the

arrival of about 10,000 communist supporters of

the Greek Civil War of 1949. The Soviet census for

1970 showed 57,800 persons of Greek origin. The

Soviet census for 1989 had 98,500 Greeks in

Ukraine and 91,700 Greeks in Russia. The 2001

census for Ukraine reported 92,500 Greeks.

See also: NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, TSARIST; ORTHODOXY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Herlihy, Patricia. (1979–1980). “Greek Merchants in

Odessa in the Nineteenth Century.” Eucharisterion:

Essays Presented to Omeljan Pritsak on His Sixtieth

Birthday by his Colleagues and Students. Harvard

Ukrainian Studies 3–4(1):399–420.

Herlihy, Patricia. (1989). “The Greek Community in

Odessa, 1861–1917.” Journal of Modern Greek Stud-

ies 7:235–252.

Prousis, Theophilus C. (1994). Russian Society and the

Greek Revolution. DeKalb: Northern Illinois Univer-

sity Press.

Rostovtzeff, Michael I. (1922). Iranians and Greeks in

South Russia. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

P

ATRICIA

H

ERLIHY

GREEN MOVEMENT

Green Movement is the term used to describe peas-

ant resistance to the Bolshevik government during

the Russian Civil War.

The first rebellions against the Bolshevik gov-

ernment began in 1918 and increased with fre-

quency and intensity through the civil war period.

In 1918 and 1919 peasant rebellions were poorly

organized and localized affairs, easily suppressed by

small punitive expeditions. In 1920, however, after

the defeat of the White armies, the Bolsheviks faced

large, well-organized peasant insurgent movements

in Tambov, the Volga and Urals regions, Ukraine,

and Siberia.

The causes of the rebellions were similar. Af-

ter the failure of Committees of the Rural Poor to

bring a reliable government to the countryside,

the Bolshevik regime relied on armed detachments

to procure grain and recruits, and to stop the black

market in food and consumer goods. The depre-

dations of these detachments, the only represen-

tatives of the Soviet government that most

peasants saw, became increasingly severe as war

communism ground down the Russian economy.

By 1920, many peasants had little grain left, even

as communist food supply organizations made

greater demands on them. Large numbers of

young men—deserters and draft-dodgers from the

Red Army—hid in villages and the surrounding

countryside from armed detachments sent to

gather them.

The Soviet-Polish war, beginning in August

1920, increased the demands on peasants for food

and recruits, and stripped the provinces of trained,

motivated troops. This allowed peasant uprisings

that were initially limited to a small area to grow,

with armed bands finding willing recruits from the

mass of deserters and draft-dodgers. By early 1921

much of the countryside was unsafe even for large

Red Army detachments.

The Green Movement of 1920 and 1921 was

qualitatively different from the peasant rebellions

the communist government had faced in 1918 or

1919. While many peasant insurgents fought in

small independent bands, Alexander Antonov’s In-

surgent Army in Tambov and Nestor Makhno’s

forces in Ukraine were organized militias whose

members had military training. Enjoying strong

support from political organizations (often made

up of local SRs [Socialist Revolutionists], Anar-

chists, or even former Bolsheviks), they established

an underground government that provided food,

horses, and excellent intelligence to the insurgents,

and terrorized local communists and their sup-

porters. They were much harder to defeat.

By February 1921 the communist government

suspended grain procurements in much of Russia

and Ukraine, and in March, at the Tenth Party Con-

gress, private trade in grain was legalized. The end

of the Soviet-Polish war in March also freed elite

armed forces to turn against the insurgents. In the

summer of 1921 hundreds of thousands of Red

Army soldiers, backed by airplanes, armored cars,

and artillery, attacked the insurgent forces. In their

wake followed the Cheka, who eliminated support

for the insurgents by holding family members

GREEN MOVEMENT

607

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

hostage, making villages collectively responsible for

guerilla attacks, shooting suspected supporters of

the insurgents, and sending thousands more to

concentration camps. Facing drought and terror,

and with the abolition of forced grain procurement

and military conscription, support for the Green

Movement collapsed by September 1921. A few

leaders, such as Makhno, slipped across the border,

but most were hunted down and killed, such as

Antonov, who died in a shootout in June 1922.

See also: CIVIL WAR OF 1917-1922; COMMITTEES OF THE

VILLAGE POOR; SOCIALIST REVOLUTIONARIES; WAR

COMMUNISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brovkin, Vladimir, ed. (1997). The Bolsheviks in Russian

Society. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Figes, Orlando. (1989). Peasant Russia, Civil War: The

Volga Countryside in Revolution, 1917–1921. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Malet, Michael. (1982). Nestor Makhno in the Russian Civil

War. London: Macmillan.

Radkey, Oliver. (1976). The Unknown Civil War in Soviet

Russia. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press.

A. D

ELANO

D

U

G

ARM

GRIBOEDOV, ALEXANDER SERGEYEVICH

(1795–1829), dramatist and diplomat.

Alexander Griboedov is best known as the au-

thor of Woe from Wit (Gore ot uma). The first Rus-

sian comedy of manners, the play was written in

1823, but not published until 1833 because of cen-

sorship.

Born in Moscow as the son of a military offi-

cer, Griboedov showed talent at an early age in a

number of areas. He was admitted to Moscow Uni-

versity at the age of eleven. By the age of sixteen

he had graduated in literature, law, mathematics,

and natural sciences. He also had a gift for music.

The Napoleonic invasion prevented him from pur-

suing a doctorate. He served in the military from

1812 to 1816. After the war he entered the civil

service in the ministry of foreign affairs. In 1818

he was sent to Persia (Iran) as secretary to the Rus-

sian mission. There Griboedov added Arabic and

Persian to the long list of foreign languages he had

mastered (French, German, Italian, and English). In

1821 he transferred to service in the Caucasus, but

took a leave of absence in St. Petersburg and

Moscow from February 1823 to May 1825 to write

Woe from Wit. Although Griboedov was back in the

Caucasus by December of 1825, he was neverthe-

less summoned under arrest for his alleged in-

volvement in the abortive Decembrist uprising of

that time. After extensive interrogations, however,

he was cleared of suspicion and returned to his

diplomatic post. Griboedov negotiated the peace

treaty of 1828 that ended the Russo-Persian War.

As a reward for his wits, he was appointed Rus-

sian minister in Tehran in 1828, where—in ironic

mockery of his own play’s title—he was murdered

in January 1829 by religious fanatics who attacked

the Russian embassy. The twentieth-century nov-

elist Yuri Tynianov wrote about Griboedov’s death

in Death and Diplomacy in Persia (1938).

Woe from Wit, composed in rhymed verse, is a

seminal work in Russian culture. Many lines from

the play have entered everyday Russian speech as

quotations or aphorisms. Its hero, Chatsky, is the

prototype of the so-called superfluous man, who

criticizes social and political conditions in his coun-

try but does nothing to bring about a change. In

addition to the gap between generations, the con-

cept of service is a key theme. In a monolithic coun-

try with minimal private enterprise, a man’s career

choices were either civil or military. Griboedov

mocks as shallow and morally irresponsible the

character Famusov, who says in the play: “For me,

whether it is business matters or not, my custom

is, once it’s signed, the burden is off my shoulders.”

As for military service, the hero Chatsky prefers to

serve the cause and not specific personalities. He

says to Famusov: “I should be pleased to serve, but

worming oneself into one’s favor is sickening”

(Sluzhit’ by rad, prisluzhivat’sia toshno). Famusov

rejects such serious loyalty to a higher cause, rem-

iniscing fondly of his uncle who stumbled and hurt

himself while in court. When Catherine the Great

showed amusement, the uncle deliberately fell

again as a way to please her. Here Griboedov ap-

pears to counter the poet Gavryl Romanovich

Derzhavin’s ode to Catherine (“Felitsa”), written in

1789, in which Catherine is praised as someone

who treats subordinates respectfully. The play con-

tains an extensive gallery of satirical portraits that

continue to hold relevance to contemporary audi-

ences in Russia and around the world.

See also: THEATER

GRIBOEDOV, ALEXANDER SERGEYEVICH

608

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Tynianov, Iurii Nikolaevich. (1975). Death and Diplomacy

in Persia, 2nd ed. Westport, CT: Hyperion.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

GRIGORENKO, PETER GRIGORIEVICH

(1907–1987), leading Soviet human rights activist.

Born in Ukraine, Peter Grigorenko was a dec-

orated war hero during World War II. He rose to

the rank of Major General in 1959. In 1964 Grig-

orenko was arrested for participation in the Soci-

ety for the Restoration of Leninist Principles, which

warned of the reemergence of a Stalinist cult of per-

sonality. For fifteen months he was in psychiatric

hospitals and prisons before being released in 1965.

Stripped of a military pension, denied professional

work, Grigorenko, at age 58, emerged as a tireless

campaigner for human rights. He became a mythic

figure among Crimean Tatars for aiding their fight

for national rights. He organized demonstrations

at dissident trials in the late 1960s and wrote and

signed petitions on behalf of dissidents. He attacked

the use of psychiatric confinement as a method of

punishing political prisoners. For his troubles, he

was arrested again, in Tashkent on May 7, 1969,

and held in psychiatric confinement until 1974. He

subsequently became one of the founding members

of the Moscow Helsinki Group, established after the

signing of the Helsinki Accords in 1975. On No-

vember 30, 1977, Grigorenko flew to New York

with his wife and a son for emergency surgery.

While there, he was stripped of his Soviet citizen-

ship. Peter Reddaway, writing in 1972 about the

Soviet human rights movement, said “if one per-

son had to be singled out as having inspired the

different groups within the Democratic movement

more than anyone else, then it would surely be

[Grigorenko]. Indeed he became, while free, in an

informal way the movement’s leader.” Grigorenko

died in New York City in 1987.

See also: DISSIDENT MOVEMENT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexeyeva, Lyudmila. (1985). Soviet Dissent: Contempo-

rary Movements for National, Religious and Human

Rights. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Grigorenko, Petr. (1982). Memoirs. New York: Norton.

Reddaway, Peter. (1972). Uncensored Russia: Protest and

Dissent in the Soviet Union. New York: American Her-

itage Press.

J

ONATHAN

W

EILER

GRISHIN, VIKTOR DMITRIEVICH

(1914–1992), member of the Politburo of the Com-

munist Party of the Soviet Union.

Twice decorated Hero of Socialist Labor (1974,

1984), Viktor Grishin was one of the highest-

ranking members of the Communist Party of the

Soviet Union (CPSU) on the eve of Michael S.

Gorbachev’s selection as party leader. Born in

Moscow, he received his degree in geodesy in

1932. From 1938 to 1940 he served in the Red

Army, during which time he became a member of

the CPSU. Following his discharge from the army

in 1941, he was assigned to duties in the Moscow

Party organization.

Grishin entered the upper echelons of the party

when he was made a member of the Central Com-

mittee of the CPSU in 1952. He took on additional

responsibilities as the head of Soviet professional

unions in 1956, a position he held until 1967. In

1961 he was made a candidate of the Politburo, and

in 1967 he became First Secretary of the Moscow

Party organization, one of the most powerful posts

in the CPSU. By 1971, he was a full member of the

Politburo.

Grishin was one of Gorbachev’s rivals for the

post of General Secretary in 1985. In order to en-

sure the loyalty of the Moscow Party organization,

Gorbachev had Grishin removed from both the

Politburo and the Moscow Party organization in

1986. He was replaced in both posts by Boris

Yeltsin. Grishin was retired from the CPSU and

lived on a party pension until his death in 1992.

See also: CENTRAL COMMITTEE; GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL

SERGEYEVICH; MOSCOW; POLITBURO

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mawdsley, Evan, and White, Stephen. (2000). The Soviet

Elite from Lenin to Gorbachev: The Central Committee

and Its Members, 1917–1991. Oxford: Oxford Uni-

versity Press.

T

ERRY

D. C

LARK

GRISHIN, VIKTOR DMITRIEVICH

609

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

GRIVNA

A Russian monetary and weight unit used from the

ninth or tenth century to the eighteenth century.

Initially the grivna was a unit of account

(twenty-five dirhams or Islamic silver coins) and a

unit of weight (c. 68 grams, or 2.4 ounces), used

interchangeably for denominating imported coined

silver. Since foreign coins fluctuated in weight and

fineness and diminished in import frequency, by

the late tenth century the grivna weighed around

51.2 grams (1.8 ounces) and equaled fifty cut

dirhams. By the eleventh century, the ratio of coins

to weight of a grivna was further altered with the

appearance of a rodlike, or Novgorodian type, sil-

ver ingot in northern Rus, weighing around 200

grams (7 ounces). This unit, called mark in Ger-

man, like the silver itself, was imported from west-

ern and central Europe to northern Russia via the

Baltic. Consequently, in Novgorod there developed

a 1:4 relationship between the silver ingot, called

grivna of silver, and the old grivna, or grivna of

kunas. Both units diffused outside of Novgorod to

other parts of Russia, including the Golden Horde,

but the relationship of the grivna of kunas to the

grivna of silver fluctuated throughout the lands

until the fifteenth century, when the ingots were

replaced by Russian coins. However, the term

grivna (grivenka) and the 200 grams (7 ounces) it

represented remained in Russian metrology until

the eighteenth century.

The southern Rus lands also manufactured and

used silver grivna ingots, but they were hexagonal

in shape and, following the weight of the Byzan-

tine litra, weighed around 160 grams (5.6 ounces).

These Kievan-type ingots were known in southern

Rus from the early eleventh century until the Mon-

gol conquest.

See also: ALTYN; DENGA; KOPECK; RUBLE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Noonan, Thomas S. (1987). “The Monetary History of

Kiev in the pre-Mongol Period.” Harvard Ukrainian

Studies 11:384–443.

Pritsak, Omeljan. (1998). The Origins of the Old Rus’

Weights and Monetary Systems. Cambridge, MA: Har-

vard Ukrainian Research Institute.

Spassky, Ivan Georgievich. (1967). The Russian Monetary

System: A Historico-Numismatic Survey, tr. Z. I. Gor-

ishina and rev. L. S. Forrer. Amsterdam: Jacques

Schulman.

R

OMAN

K. K

OVALEV

GROMOV, BORIS VSEVOLODOVICH

(b. 1943), Commander of Fortieth Army in Afghani-

stan, Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs, Deputy

Minister of Defense, Member of the State Duma,

and Governor of Moscow Oblast (District).

Boris Gromov had a distinguished career as a

professional soldier in the Soviet Ground Forces. In

1962 he graduated from the Suvorov Military

School in Kalinin. From there he attended the Higher

Combined Arms Command School in Leningrad and

was commissioned in the Soviet Army in 1965.

From 1965 Gromov held command and staff as-

signments. In 1974 he graduated from the Frunze

Military Academy. From 1980 to 1982 he com-

manded a motorized rifle division in Afghanistan;

on his return to the Soviet Union, he attended the

Voroshilov Military Academy of the General Staff,

graduating in 1984. In 1987 Gromov returned to

Afghanistan as Commander of the Fortieth Army

and led the withdrawal of Soviet forces from Af-

ghanistan, which was completed in February 1989.

His next assignment was that of Commander of the

Kiev Military District, a post he held until Novem-

ber 1990, when, in an unexpected move, he was

named First Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs and

Commander of Internal Troops. He held that post

until August 1991. In the aftermath of the unsuc-

cessful coup against Gorbachev, Gromov was ap-

pointed First Deputy Commander of Soviet (later

Commonwealth of Independent States) Conven-

tional Forces. In May 1992 he was appointed

Deputy Minister of Defense of the Russian Federa-

tion. In 1994 Gromov joined a group of senior Russ-

ian officers who broke with Minister of Defense

Pavel Grachev and publicly warned against mili-

tary intervention in Chechnya when Russian forces

were unprepared. In the aftermath of that act,

Gromov was moved to the Ministry of Foreign Af-

fairs. In 1995 he stood for election to the State

Duma on the My Fatherland Party ticket and won.

In January 2000 he was elected Governor of the

Moscow Oblast. Gromov received the Hero of the

Soviet Union award for his service as army com-

mander in Afghanistan.

See also: AFGHANISTAN, RELATIONS WITH; MILITARY, SO-

VIET AND POST-SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baev, Pavel K. (1996). The Russian Army in a Time of Trou-

bles. London: Sage Publications.

GRIVNA

610

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Gromov, Boris. (2001). “Wounds of a Bitter War.” New

York Times, No. 2767 (October 01, 2001), Op-Ed.

J

ACOB

W. K

IPP

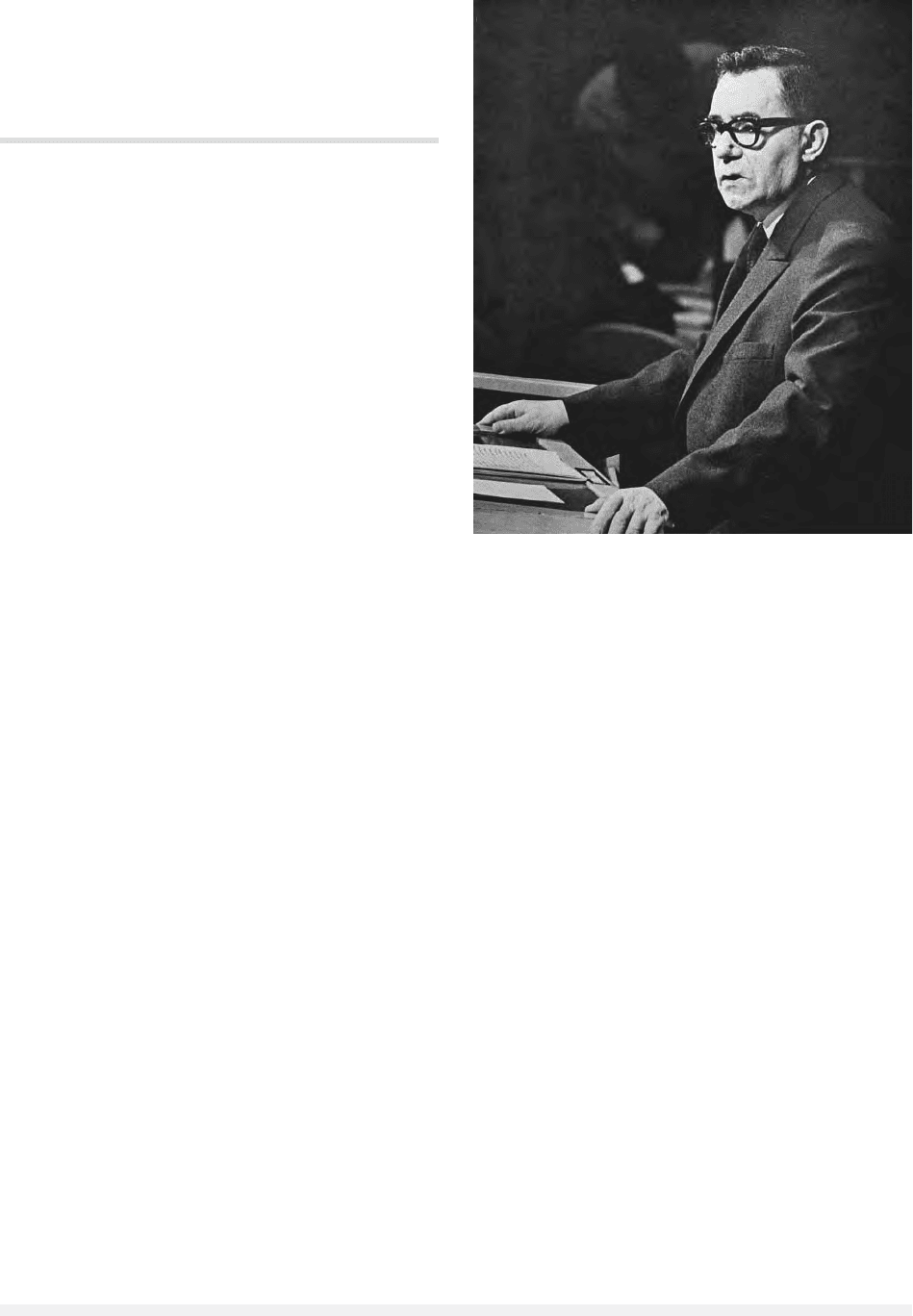

GROMYKO, ANDREI ANDREYEVICH

(1909–1989), Soviet foreign minister and president.

Andrei Gromyko was born into a peasant fam-

ily in the village of Starye Gromyki in Belorussia.

He joined the Communist Party in 1931. He com-

pleted study at the Minsk Agricultural Institute in

1932 and gained a Candidate of Economics degree

from the All-Union Scientific Research Institute of

Agronomy in 1936. From 1936 to 1939 he was a

senior researcher in the Institute of Economics of

the Academy of Sciences and the executive editor-

ial secretary of the journal Problemy ekonomiki; he

later gained a doctorate of Economics in 1956. In

1939 Gromyko switched to diplomatic work and

became section head for the Americas in the Peo-

ple’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs. Later that

year he became counselor in the Soviet Embassy in

Washington. Between 1943 and 1946 he was So-

viet ambassador to the United States and Cuba.

During this time, he was involved in the Dumbar-

ton Oaks Conference (1944) called to produce the

UN Charter and the 1945 San Francisco conference

establishing the United Nations. He also played an

organizational role in the Big Three wartime con-

ferences. From 1946 to 1948 he was the perma-

nent representative in the UN Security Council as

well as deputy (from 1949 First Deputy) minister

of foreign affairs. Except for the period 1952–1953

when he was ambassador to Great Britain, he held

the First Deputy post until he was promoted to for-

eign minister following the anti-party group affair

of 1957. Gromyko remained foreign minister un-

til July 1985, when he became chairman of the

Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, effectively Soviet

president.

Throughout his career, Gromyko was neither

highly ambitious nor a major political actor on the

domestic scene. Although a full member of the Cen-

tral Committee from 1956, he did not become a

full member of the Politburo until 1973. He devel-

oped his diplomatic skills and became the public

face of Soviet foreign policy, gaining a reputation

as a tough negotiator who never showed his hand.

He was influential in the shaping of foreign policy,

in particular détente, but he was never unchal-

lenged as the source of that policy; successive lead-

ers Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev both

sought to place their personal stamp upon foreign

policy, while there was always competition from

the International Department of the Party Central

Committee and the KGB. Gromyko formally nom-

inated Mikhail Gorbachev as General Secretary in

March 1985, and three months later was moved

from the Foreign Ministry to the presidency. The

foreign policy for which he was spokesperson dur-

ing the Brezhnev period now came under attack as

Gorbachev and his Foreign Minister Eduard She-

vardnadze embarked on a new course. Gromyko’s

most important task while he was president was

to chair a commission that recommended the re-

moval of restrictions on the ability of Crimean

Tatars to return to Crimea. Gromyko was forced

to step down from the Politburo in September

1988, and from the presidency in October 1988,

and was retired from the Central Committee in

April 1989. He was the author of many speeches

and articles on foreign affairs.

See also: BREZHNEV, LEONID ILICH; GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL

SERGEYEVICH

GROMYKO, ANDREI ANDREYEVICH

611

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Soviet foreign ministry Andrei Gromyko, nicknamed “Mr.

Nyet” by his Western counterparts, addresses the U.N. General

Assembly. U

NITED

N

ATIONS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Edmonds, Robin. (1983). Soviet Foreign Policy: The Brezh-

nev Years. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gromyko, Andrei. (1989). Memories, tr. Harold Shuk-

man. London: Arrow Books.

The Tauris Soviet Directory. The Elite of the USSR Today.

(1989). London: I. B. Tauris.

G

RAEME

G

ILL

GROSSMAN, VASILY SEMENOVICH

(1905–1964), one of the most important Russian

novelists of the twentieth century who became in-

creasingly disillusioned with the Soviet system.

Vasily Grossman was born in 1905 in the town

of Berdichev in Ukraine. He spent the years from

1910 to 1914 in Switzerland with his mother and

attended high school in Kiev. He received a degree

in chemical engineering from Moscow University

in 1929 and worked in various engineering jobs

until becoming a full-time writer in 1934. He pub-

lished his first news article in 1928 and his first

short story in 1934 and became a prolific writer of

fiction during the 1930s. He published a long novel

about the civil war entitled Stepan Kolchugin be-

tween 1937 and 1940. In 1938, his wife was ar-

rested, but Grossman wrote to Nikolai Yezhov and

achieved her release.

During World War II, Grossman served as a

correspondent for Red Star (Krasnaya Zvezda) and

spent the entire war at the front. His writing dur-

ing the war years was immensely popular, and his

words are inscribed on the war memorial at Stal-

ingrad (now Volgograd). He also began writing

short stories, which were collected in titles such as

The People are Immortal. However, from that per-

spective, he also began to doubt the abilities of the

systems that organized the war effort.

Grossman’s postwar projects were often chal-

lenging to the Soviet system, and several were not

published until long after their completion. Begin-

ning in 1943, Grossman and Ilya Ehrenburg began

to collect personal accounts of the Holocaust on the

territories of the Soviet Union, entitled the Black

Book of Russian Jewry. Grossman became the editor

of the collection in 1945 and continued to prepare

it for publication. The printing plates were actually

completed, but in 1946, as anti-Semitism began to

increase and Josef Stalin turned against the Jewish

Anti-Fascist Committee, they were removed from

the printing plant. The book would not be pub-

lished in any part of the former USSR until 1994.

His postwar fiction about the war generated in-

tense criticism from Soviet officials. His novel For

a Just Cause (Za pravoye delo), published in 1952,

led to attacks for its lack of proper ideological fo-

cus. His most contemplative piece about the war,

Life and Fate (Zhizn i sudba) was arrested by the

KGB in 1961. Although they seized Grossman’s

copy of the manuscript, another had already been

hidden elsewhere and preserved. Often compared to

Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, the novel bitterly at-

tacks Stalin and the Soviet system for failures. He

focuses on the suffering of one family at the hands

of large forces outside of their control. In it he

touches upon the Gulags, the Holocaust, and the

repressions that accompanied the heroism of ordi-

nary Soviets. After twenty years, it was smuggled

out of the Soviet Union on microfilm and published

in the West. His last novel, Everything is in Flux (Vse

techet), is an angry indictment of Soviet society and

was distributed only in Samizdat.

On his death from cancer in 1964, Grossman

disappeared from public Soviet literary discussions,

only reappearing under Mikhail Gorbachev. In ret-

rospect, Grossman’s writing has been acknowl-

edged as some of the most significant Russian

literature of the twentieth century.

See also: CENSORSHIP; JEWS; SAMIZDAT; STALIN, JOSEF

VISSARIONOVICH; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ehrenburg, Ilya, and Grossman, Vasily. (2002). The Com-

plete Black Book of Russian Jewry, tr. David Patterson.

New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Garrard, John, and Garrard, Carol. (1996). The Bones of

Berdichev: The Life and Fate of Vasily Grossman. New

York: Simon and Schuster.

Grossman, Vasily. (1985). Life and Fate, tr. Robert Chan-

dler. New York: Harper & Row

K

ARL

E. L

OEWENSTEIN

GUARDS, REGIMENTS OF

The Russian Imperial Guards regiments originated

in the two so-called play regiments that the young

Tsar Peter I created during the 1680s. They took

their names, Preobrazhensky and Semonovsky, from

the villages in which they had originally taken

GROSSMAN, VASILY SEMENOVICH

612

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY