Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

GENETICISTS

Adherents of a prescriptive theoretical model for

economic development planning in a controversy

of the 1920s.

The geneticists participated in an important the-

oretical controversy with the teleologists over the

nature and potential limits to economic planning.

The issue was fundamental and cut to the heart of

the very possibility of central planning. Would a

central planning agency be constrained by economic

laws, such as supply and demand, or by other fixed

economic regularities, such as sector proportions,

or could planners operate to shape the economic fu-

ture according to their own preferences?

The geneticists argued that it was necessary to

base economic plans on careful study of economic

laws and historical determinants of economic ac-

tivity. The past and certain general laws con-

strained any plan outcome. In this view, planning

was essentially a form of forecasting. The teleolo-

gists argued on the contrary that planners should

set their objectives independently of such con-

straints, that planning could seek to override mar-

ket forces to achieve maximum results focused on

decisive development variables, such as investment.

Proponents of the geneticist view included Nikolai

Kondratiev and Vladimir Groman and were well

disposed to the New Economic Policy (NEP) of the

1920s. The teleologists included Stanislav Stru-

milin and Pavel Feldman who were less well dis-

posed toward the NEP and believed it would be

possible to force economic development through

binding industrial and enterprising targets.

The argument became quite heated and over-

simplified. The degree of freedom of action that the

geneticists allowed planners was miniscule, and it

appeared that planning would involve little more

than filling in plan output cells based almost en-

tirely on historical carryover variables. The teleol-

ogists claimed a degree of latitude to planners that

was almost total. In the end the geneticists lost,

and Soviet planning followed the teleologists’ ap-

proach: it consisted of a set of comprehensive tar-

gets designed to force both the pace and the

character of development. Soviet experience over

the long run, however, suggests that the geneti-

cists were closer to the mark concerning constraints

on development.

See also: ECONOMIC GROWTH, SOVIET; KONDRATIEV,

NIKOLAI DMITRIEVICH; NEW ECONOMIC POLICY; TELE-

OLOGICAL PLANNING

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gregory, Paul R., and Stuart, Robert C. (1990). Soviet Eco-

nomic Structure and Performance, 4th ed. New York:

HarperCollins.

Millar, James R. (1981). The ABCs of Soviet Socialism. Ur-

bana: University of Illinois Press.

J

AMES

R. M

ILLAR

GENEVA SUMMIT OF 1985

A summit meeting of U.S. president Ronald Reagan

and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev took place in

Geneva, Switzerland, on November 19–20, 1985.

It was the first summit meeting of the two men,

and indeed of any American and Soviet leaders in

six years. Relations between the two countries had

become much more tense after the Soviet military

intervention in Afghanistan at the end of 1979,

and the election a year later of an American pres-

ident critical of the previous era of détente and dis-

posed to mount a sharp challenge, even a crusade,

against the leaders of an evil empire. However, by

1985 President Reagan was ready to meet with a

new Soviet leader and test the possibility of relax-

ing tensions.

Although the Geneva Summit did not lead to

any formal agreements, it represented a successful

engagement of the two leaders in a renewed dia-

logue, and marked the first step toward several later

summit meetings and a gradual significant change

in the relationship of the two countries. Both Rea-

gan and Gorbachev placed a high premium on di-

rect personal encounter and evaluation, and they

developed a mutual confidence that helped steer na-

tional policies.

Gorbachev argued strongly at Geneva for a re-

consideration of Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initia-

tive (SDI, or Star Wars), but to no avail. He did,

however, obtain agreement to a joint statement

that the two countries would “not seek to achieve

military superiority” (as well as reaffirmation that

“a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be

fought”). This joint statement was given some

prominence in Soviet evaluations of the summit,

and was used by Gorbachev in his redefinition of

Soviet security requirements. Although disappointed

at Reagan’s unyielding stance on SDI, Gorbachev

had come to realize that it represented a personal

moral commitment by Reagan and was not sim-

ply a scheme of the American military-industrial

complex.

GENEVA SUMMIT OF 1985

543

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The Geneva summit not only established a per-

sonal bond between Reagan and Gorbachev, but for

the first time involved Reagan fully in the execu-

tion of a strategy for diplomatic reengagement with

the Soviet Union, a strategy that Secretary of State

George Schultz had been advocating since 1983 de-

spite the opposition of a number of members of the

administration. For Gorbachev, the summit signi-

fied recognition by the leader of the other super-

power. Although it was too early to predict the

consequences, in retrospect it became clear that the

renewed dialogue at the highest level would in time

lead to extraordinary changes, ultimately con-

tributing to the end of the Cold War.

See also: COLD WAR; STRATEGIC DEFENSE INITIATIVE;

UNITED STATES, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Garthoff, Raymond L. (1994). The Great Transition:

American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War.

Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Shultz, George P. (1993). Turmoil and Triumph: My Years

as Secretary of State. New York: Charles Scribner’s

Sons.

R

AYMOND

L. G

ARTHOFF

GENOA CONFERENCE

The Genoa Conference, convened in April and May

1922, was an international diplomatic meeting of

twenty-nine states, including Britain, France, Italy,

Germany, Russia, and Japan, but not the United

States. It was summoned to resolve several prob-

lems in the postwar restructuring of Europe, in-

cluding the desire to reintegrate Soviet Russia and

Weimar Germany into the political and economic

life of Europe on terms favorable to the dominant

Anglo-French alliance. The Allies wanted Moscow

to repay foreign debts incurred by previous Rus-

sian governments, compensate foreign owners of

property nationalized by the Bolsheviks, and guar-

antee that revolutionary propaganda would cease

throughout their empires.

The invitation for Soviet participation in the

conference facilitated Moscow’s drive for peaceful

coexistence with the West and for the substantial

foreign trade, technology, loans, and investment

required by the New Economic Policy. Both sides

failed to achieve their objectives. The Anglo-French

side pressed for the broadest possible repayment of

Russian obligations, but offered little in loans and

trade credits. The Soviets pushed for as much West-

ern financed trade and technological assistance as

possible, but conditioned limited debt repayment

on the recovery of the Soviet economy. Moreover,

Foreign Commissar Georgy Chicherin angered the

Western representatives by calling for comprehen-

sive disarmament and representation for the colo-

nial peoples in the British and French empires. The

impasse between Russia and the West, combined

with a similar stalemate between the Anglo-French

side and Germany, caused Berlin and Moscow to

conclude a political and economic pact, the Rapallo

Treaty. Thus, the Genoa Conference ended in fail-

ure, though the USSR succeeded in gaining recog-

nition as an integral part of European diplomacy

and in bolstering its relationship with Germany.

See also: WORLD WAR I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fink, Carole. (1984). The Genoa Conference: European Diplo-

macy, 1921–1922. Chapel Hill: University of North

Carolina Press.

White, Stephen. (1985). The Origins of Detente: The Genoa

Conference and Soviet-Western Relations, 1921–1922.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

T

EDDY

J. U

LDRICKS

GENOCIDE

Genocide is a word coined after World War II to

designate a phenomenon that was not new—the

extermination, usually by a government, of a group

of people for their ethnic, religious, racial, or po-

litical belonging. The term implies both a deliber-

ate intent as well as a systematic approach in its

implementation. Until international law came to

terms with the Holocaust of the Jewish people in

Europe, the extermination of such groups was con-

sidered as a crime against humanity or as a war

crime, since wars tended to provide governments

the opportunity to execute their designs. In a res-

olution adopted in 1946, the U.N. General Assem-

bly declared genocide a crime under international

law—its perpetrators to be held accountable for

their actions. Two years later, with the full sup-

port of the USSR, the same body approved the Con-

vention on the Prevention and Punishment of the

Crime of Genocide that went into effect soon after.

GENOA CONFERENCE

544

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Article II of the Convention defines genocide as

“any of the following acts committed with intent

to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethni-

cal, racial, or religious group, as such: a) killing

members of the group; b) causing serious bodily

or mental harm to members of the group; c) de-

liberately inflicting on the group conditions of life

calculated to bring about its physical destruction

in whole or in part; d) imposing measures intended

to prevent births within the group; and e) forcibly

transferring children of the group to another.” Ar-

ticle III of the Convention stipulated that those who

commit such acts as well as those who support or

incite them are to be punished. The Convention

provided for an International Court of Justice to

try cases of genocide. The Tribunal was established

only in 2002. Meanwhile, the genocide of Ibos in

Nigeria during the 1970s was not considered by

any court; those responsible for the Cambodian

genocide during the 1980s were tried by a domes-

tic court some years later; the genocide during the

mid 1990s of the Tutsis by the Hutus in Rwanda

was finally considered by an international court in

Tanzania, while an international tribunal in The

Hague undertook a review of charges of genocide

against Serb, Croat, and other leaders responsible

for crimes during the Balkan crisis following the

collapse of Yugoslavia during the early 1990s.

Two well-known cases of genocide have affected

Russia and the Soviet Union. The Young Turk Gov-

ernment of the Ottoman Empire implemented a

deliberate and systematic deportation and extermi-

nation of its Armenian population during World

War I in the Western part of historic Armenia un-

der its domination. Eastern Armenia had been inte-

grated into the Russian Empire by 1828. Russia,

along with other European powers, had pressed Ot-

toman governments to introduce reforms in Ot-

toman Armenia and Russian Armenians were

involved in the efforts to produce change. Close to

one million Armenians perished as a result. The

Russian army, already at war with the Ottomans,

was instrumental in saving the population of some

cities near its border, assisted by a Russian Armen-

ian Volunteer Corps. Many of the survivors of the

Genocide ended up in Russian Armenia and south-

ern Russia. Others emigrated after 1920 to Soviet

Armenia, mainly from the Middle East during the

years following World War II. A few of the Young

Turk leaders responsible for the Armenian genocide

were tried by a Turkish court following their de-

feat in the war and condemned, largely in absentia,

but the trials were halted due to changes in the do-

mestic and international environment.

During World War II Nazi advances into Soviet

territory provided an opportunity to German forces

to extend the policy of extermination of Jews into

those territories. Nazi leaders responsible for the

Holocaust were tried and condemned to various sen-

tences at Nuremberg, Germany, following the war.

Russian and Soviet governments have tolerated

or implemented policies that, while not necessarily

qualified as genocides, raise questions relevant to

the subject. Pogroms against Russian Jews during

the last decades of the Romanov Empire and the de-

portation of the Tatars from Crimea, Chechens and

other peoples from their Autonomous Republics

within Russia, and Mtskhetan Turks from Georgia

during and immediately following World War II on

suspicion of collaboration with the Germans reflect

a propensity on the part of Russia and Soviet gov-

ernments to resolve perceived political problems

through punishment of whole groups. Equally im-

portant, the politically motivated purges engineered

by Josef Stalin and his collaborators of the Com-

munist Party and Soviet government officials and

their families and various punitive actions against

whole populations claimed the lives of millions of

citizens between 1929 and 1939.

In one case, Soviet policy has been designated

as genocidal by some specialists. As a result of the

forced collectivization of farms during the early

1930s, Ukraine suffered a famine, exacerbated by

a severe drought, which claimed as many as five

million lives. The Soviet government’s refusal to

recognize the scope of the disaster and provide re-

lief is seen as a deliberate policy of extermination.

See also: NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, TSARIST; WORLD WAR II.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Courtois, Stéphane. (1999). The Black Book of Communism:

Crimes, Terror, Repression, tr. Jonathan Murphy and

Mark Kramer. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Fein, Helen. (1979). Accounting for Genocide: National Re-

sponses and Jewish Victimization during the Holocaust.

New York: The Free Press.

Walliman, Isidor, and Dobkowski, Michael N., eds.

(1987). Genocide and the Modern Age: Etiology and Case

Studies of Mass Death. New York: Greenwood Press.

Weiner, Amir. (2000). Making Sense of War: The Second

World War and the Fate of the Bolshevik Revolution.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

G

ERARD

J. L

IBARIDIAN

GENOCIDE

545

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

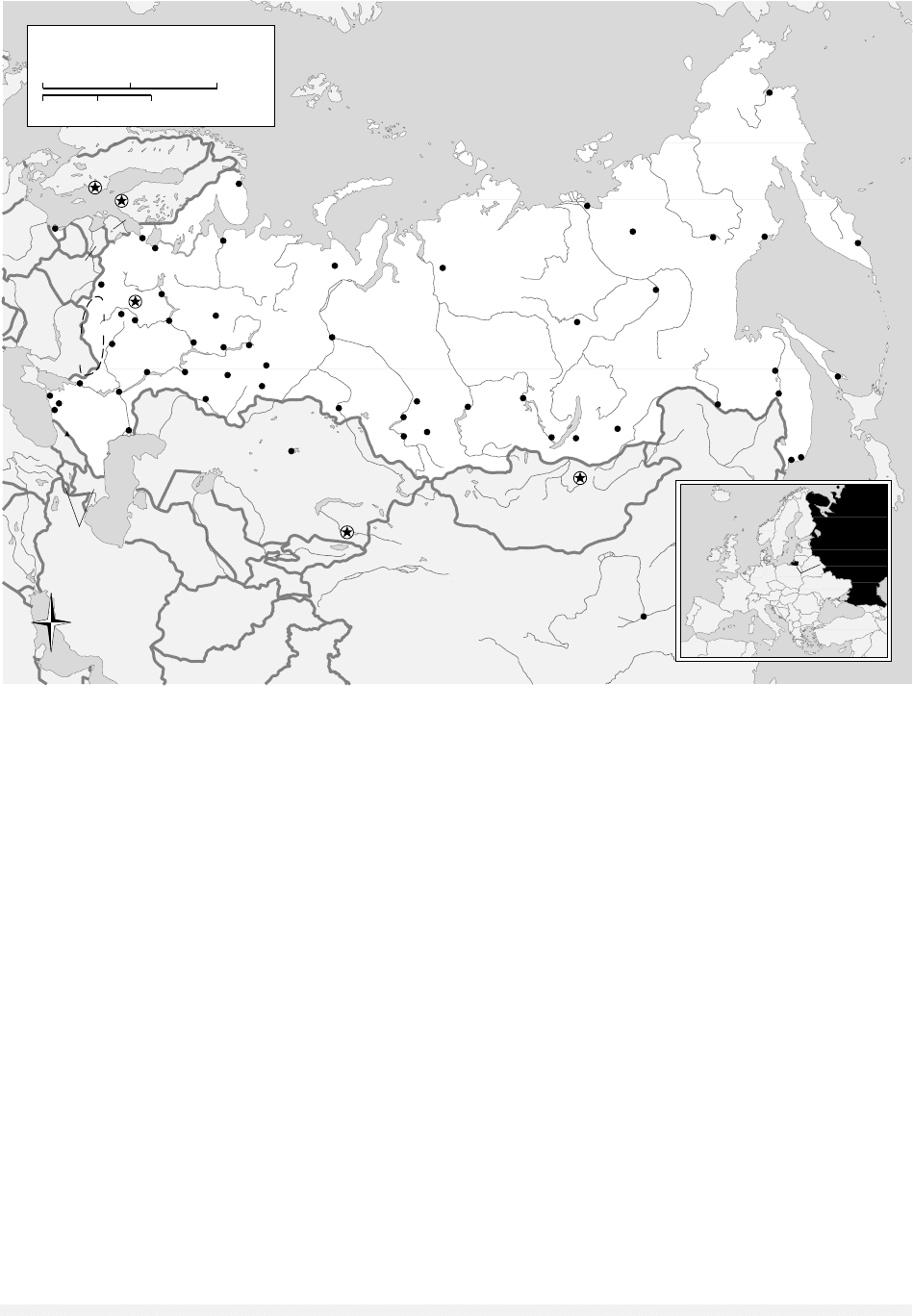

GEOGRAPHY

Russia is the world’s largest country, 1.7 times

larger than second-place Canada, ten times larger

than Alaska, and twenty-five times larger than

Texas. It stretches from 19° E Longitude in the west

to 169° W Longitude in the east, spanning 5,700

miles (9,180 kilometers) and eleven time zones. If

Russia were superimposed on North America with

St. Petersburg in Anchorage, Alaska, the Chukchi

Peninsula would touch Oslo, Norway, halfway

around the globe. Thus, when Russians are eating

supper on any given day in St. Petersburg, the

Chukchi are breakfasting on the next. From its

southernmost point (42° N) to its northernmost is-

lands (82° N), the width of Russia exceeds the length

of the contiguous United States.

Russia’s size guarantees a generous endowment

of natural features and raw materials. The country

contains the world’s broadest lowlands, swamps,

grasslands, and forests. In the Greater Caucasus

Mountains towers Europe’s highest mountain, Mt.

Elbrus. Flowing out of the Valday Hills northwest

of Moscow and into the world’s largest lake, the

Caspian Sea, is Europe’s longest river, the “Mother

Volga.” Almost three thousand miles to the east,

in Eastern Siberia, is Lake Baikal, the world’s deep-

est lake. The Russian raw material base is easily the

world’s most extensive. The country ranks first or

second in the annual production of many of the

world’s strategic minerals. Historically, Russia’s

size has ensured defense in depth. Napoleon and

Hitler learned this the hard way in 1812 and in the

1940s, respectively.

Because Russia is such a northerly country,

however, much of the land is unsuitable for hu-

man habitation. Ninety percent of Russia is north

of the 50th parallel, which means that Russian

farmers can harvest only one crop per field per

year. Three-fourths of Russia is more than 250

miles (400 km) away from the sea. Climates are

continental rather than maritime. Great tempera-

ture ranges and low annual precipitation plague

most of the country. Therefore, only 8 percent of

Russia’s enormous landmass is suitable for farm-

ing. The quest for food is a persistent theme in

Russian history. Before 1950, famines were harsh

realities.

The Russian people thus chose to settle in the

temperate forests and steppes, avoiding the moun-

tains, coniferous forests, and tundras. The primary

zone of settlement stretches from St. Petersburg in

the northwest to Novosibirsk in Western Siberia

and back to the North Caucasus. A thin exclave of

settlement continues along the Trans-Siberian Rail-

road to Vladivostok in the Russian Far East. Except

for random mining and logging, major economic

activities are carried out in the settled area.

Russia’s size evidences great distances between

and among geographic phenomena. Accordingly, it

suffers the tyranny of geography. Many of its raw

materials are not accessible, meaning they are not

resources at all. The friction of distance—long rail

and truck hauls—accounts for high transportation

costs. Although in its entirety Russia displays great

beauty and diversity of landforms, climate, and

vegetation, close up it can be very dull because of

the space and time required between topographical

changes. Variety spread thinly over a massive land

can be monotonous. Three-fourths of the country,

for example, is a vast plain of less than 1,500 feet

(450 meters) in elevation. The typical Russian land-

scape is flat-to-rolling countryside, the mountains

relegated to the southern borders and the area east

of the Yenisey River. The Ural Mountains, which

divide Europe from Asia, are no higher than 6,200

feet (1,890 meters) and form a mere inconvenience

to passing air masses and human interaction. Rus-

sia’s average elevation is barely more than 1,000

feet (333 meters).

Russia is a fusion of two geologic platforms:

the European and the Asiatic. When these massive

plates collided 250 million years ago, they raised a

mighty mountain range, the low vestiges of which

are the Urals. West of the Urals is the North Eu-

ropean Plain, a rolling lowland occasioned by hills

left by Pleistocene glaciers. One set of hills stretches

between Moscow and Warsaw: The Smolensk-

Moscow Ridge is the only high ground between the

Russian capital and Eastern Europe and was the

route used by Napoleon’s and Hitler’s doomed

armies. Further north between Moscow and St.

Petersburg are the Valday Hills, which represent

the source of Russia’s major river systems: Volga,

Dnieper, Western Dvina, and so forth. Where it has

not been cleared for agriculture, the plain nurtures

a temperate forest of broadleaf trees, which domi-

nate in the south, and conifers, which prevail in

the north. The slightly leached gray and brown

soils of this region were first cultivated by the early

eastern Slavs.

In the south, the North European Lowland

merges with the Stavropol Upland of the North

Caucasus Foreland between the Black and Caspian

seas. Here the forests disappear, leaving only grass-

GEOGRAPHY

546

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

land, or steppe, the soils of which are Russia’s fer-

tile chernozems. Along the western and northern

shores of the Caspian Sea, desert replaces the grass-

lands. Farther south, North Caucasia merges with

the Greater Caucasus Mountains, the highest peak

of which is Mt. Elbrus (18,481 feet [5,633 meters]).

The northern part of the European Lowland

supports a northern coniferous forest, known as

taiga. The largest continuous stand of conifers in

the world, the taiga stretches from the Finnish bor-

der across Siberia and the Russian Far East to the

Pacific Ocean. Even farther north, flanking the Arc-

tic Ocean is the Russian tundra. Permafrost plagues

both the taiga and tundra, limiting their use for

anything other than logging and mineral develop-

ment. Soils are highly infertile podzols. Virtually

all of Siberia and the Russian Far East consist of ei-

ther taiga or tundra, except in the extreme south-

east, where temperate forest appears again.

East of the Urals is the West Siberian Lowland,

the world’s largest plain. The slow-moving Ob and

Irtysh rivers drain the lowland from south to

north. This orientation means that the lower

courses of the rivers are still frozen as the upper

portions thaw. The ice dam causes annual floods

that create the world’s largest swamp, the Vasyu-

gan. The Ob region contains Russia’s largest oil and

gas reservoirs. In southeastern Western Siberia is

Russia’s greatest coal field, the Kuzbas. South of

the Kuzbas are the mineral-rich Altai Mountains,

which together with the Sayan, and the Yablonovy

ranges, form the border between Russia, China, and

Mongolia.

East of the Yenisey River is the forested Central

Siberian Plateau, a broad, sparsely populated table-

land that merges farther east with the mountain

ranges of the Russian Far East. In the southeastern

corner of the plateau is a great rift valley in which

GEOGRAPHY

547

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Mt. Elbrus

18,510 ft.

5642 m.

C

A

U

C

A

S

U

S

M

T

S

.

ZAPADNO

SIBIRSKAYA

RAVNINA

REDNE

SIBIRSKOYE

PLOSKOGRYE

S

E

V

E

R

O

S

I

B

I

R

S

K

A

Y

A

N

I

Z

M

E

N

N

O

S

T

SIBERIA

Kol'skiy

Poluostrov

Severnaya

Zemlya

Poluostrov

Taymyr

Poluostrov

Kamchatka

Sakhalin

Komandorskiye

Ostrova

Wrangel I.

New

Siberian Is.

Gydanskiy

Poluostrov

Poluostrov

Yamal

Franz Josef

Land

U

R

A

L

M

O

U

N

T

A

I

N

S

Y

A

B

L

O

N

O

V

Y

Y

K

H

R

E

B

E

T

V

E

R

K

H

O

Y

A

N

S

K

K

H

R

E

B

E

T

S

T

A

N

O

V

O

Y

K

H

R

E

B

E

T

K

H

R

E

B

E

T

D

Z

H

U

G

D

Z

H

U

R

K

H

R

E

B

E

T

C

H

E

R

S

K

O

G

O

K

u

r

i

l

I

s

l

a

n

d

s

K

O

L

Y

M

A

M

T

S

.

K

O

R

Y

A

K

M

T

S

.

Black

Sea

ARCTIC OCEAN

PACIFIC

OCEAN

Bering

Sea

Barents Sea

Kara Sea

Baltic Sea

Laptev

Sea

Sea of Okhotsk

Bering Strait

East

Siberian

Sea

Chukchi

Sea

Anadyrskiy

Zaliv

T

a

t

a

r

P

r

o

l

i

v

Ozero

Baykal

A

m

u

r

O

b

'

O

b

'

I

r

t

y

s

h

L

e

n

a

L

e

n

a

V

i

l

y

u

y

A

n

g

a

r

a

K

o

l

y

m

a

I

n

d

i

g

i

r

k

a

A

l

d

a

n

O

l

e

n

e

k

D

o

n

Ladozhskoye Ozero

K

a

m

a

N

i

z

h

n

y

a

y

a

T

u

n

g

u

s

k

a

Y

e

n

i

s

e

y

V

o

l

g

a

U

r

a

l

Caspian

Sea

Orenburg

Tuapse

Novorossiysk

Smolensk

Saratov

Izhevsk

Verkhoyansk

Petropavlovsk

Kamchatskiy

Komsomol'sk

Chita

Ulan-

Ude

Bratsk

Blagoveshchensk

Anadyr'

Tiksi

Vorkuta

Kaliningrad

Kirov

Yaroslavl'

Magadan

Oymyakon

Astrakhan

Ryazan

Krasnodar

Khabarovsk

Irkutsk

Barnaul

Krasnoyarsk

Tomsk

Novokuznetsk

Noril'sk

Khanty

Manisysk

Yakutsk

Mirnyy

Vladivostok

Nakhodka

Korsakov

Xi'an

Tula

Voronezh

Murmansk

Arkhangel'sk

Syas'stroy

Rostov

Volgograd

Perm'

Yekaterinburg

Chelyabinsk

Qaraghandy

Kazan'

Samara

Ufa

Nizhniy Novgorod

Omsk

Novosibirsk

St.

Petersburg

Moscow

Ulan Bator

Alma Ata

Helsinki

Stockholm

ù

KARELIA

Kursk

Magnetic

Anomaly

CHINA

MONGOLIA

KAZAKHSTAN

TURKMENISTAN

UZBEKISTAN

AFGHANISTAN

PAKISTAN

INDIA

TAJIKISTAN

KYRGYZSTAN

IRAN

UKRAINE

AZERBAIJAN

ARMENIA

GEORGIA

BELARUS

LATVIA

LITHUANIA

FINLAND

ESTONIA

SWEDEN

JAPAN

Russia

W

S

N

E

RUSSIA

1000 Miles

0

0

1000 Kilometers

500

500

Russia, 1992 © M

ARYLAND

C

ARTOGRAPHICS

. R

EPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

.

lies Lake Baikal, “Russia’s Grand Canyon.” Equal to

Belgium in size, the world’s deepest lake gets deeper

with every earthquake.

See also: CLIMATE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lydolph, Paul E. (1990). Geography of the USSR. Elkhart

Lake, WI: Misty Valley Publishing.

Mote, Victor L. (1994). An Industrial Atlas of the Soviet

Successor States. Houston, TX: Industrial Informa-

tion Resources.

Mote, Victor L. (1998). Siberia Worlds Apart. Boulder, CO:

Westview.

Shaw, Denis J. B. (1999). Russia in the Modern World: A

New Geography. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

V

ICTOR

L. M

OTE

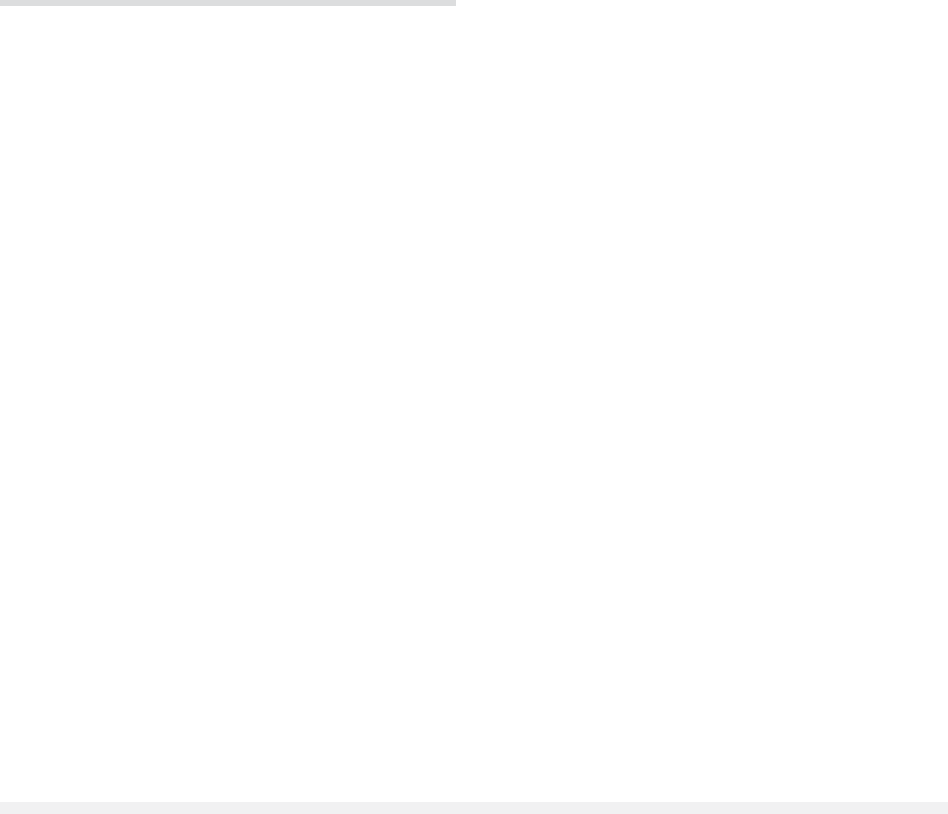

GEORGIA AND GEORGIANS

Georgia [Sak’art’velo] is among the “Newly Inde-

pendent States” to emerge from the collapse of the

Soviet Union. Its territory covers 69,700 square

kilometers, bordered by the North Caucasus re-

publics of the Russian Federation on the north,

Azerbaijan to the west, Armenia and Turkey to the

south and southwest, and the Black Sea to the east.

It includes three autonomous regions: Adjaria,

Abkhazia, and South Ossetia. The latter two have

maintained a quasi-independent status for most of

the post-Soviet period, and have been the scenes of

violence and civil war. The capital city of Tiflis, lo-

cated on the Mtkvari (or Kura) River in the heart

of Georgia, has a population of 1.2 million, ap-

proximately 22 percent of the republic’s 5.4 mil-

lion. Georgia’s head of state is a president. A

unicameral parliament is Georgia’s legislative body.

The Georgians are historically Orthodox Chris-

tians, with some conversions to Islam during times

of Muslim rule. Their language, with its own al-

phabet (thirty-three letters in the modern form), is

a member of the Kartvelian family, a group distinct

from neighboring Indo-European or Semitic lan-

guages. Speakers of Mingrelian and Svanetian, two

of the other Kartvelian languages, also consider

themselves Georgian. Laz, closely related to Min-

grelian, is spoken in Turkey. Georgia has an ethni-

cally diverse population: Georgian 70.1 percent,

Armenian 8.1 percent, Russian 6.3 percent, Azeri

5.7 percent, Ossetian 3 percent, Abkhaz 1.8 percent,

and other groups comprising 5 percent.

Georgian principalities and kingdoms began to

appear in the last few centuries of the first millen-

nium

B

.

C

.

E

, and existed alongside a well-traveled

east-west route on the peripheries of both Persian

and Greco-Roman civilizations. These influences

were mediated through their Armenian neighbors

who, with the Georgians, also maintained contacts

with Semitic cultures.

Ancient Georgian culture was split into two

major areas: east and west, divided by the Likhi

mountains. The eastern portion, known as Kartli,

or Iberia, had its center at Mtskheta, at the con-

fluence of the Aragvi and Mtkvari Rivers. When

not directly controlled by a Persian state, it still

maintained ties with the Iranian political and cul-

tural spheres. This connection lasted well into the

Christian period, when the local version of Zoroas-

trianism vied with Christianity.

Western Georgia was known by different

names, depending upon the historical source:

Colchis, Egrisi, Lazica. It had more direct ties with

Greek civilizations, as several Greek colonies had

existed along the Black Sea coast from as early as

the sixth century

B

.

C

.

E

. Western Georgia was even-

tually more directly under the control of the Ro-

man Empire, in its successive incarnations.

The conversion of the Kartli to Christianity oc-

curred in the fourth century as the Roman Empire

was beginning its own transition to Christianity.

As with other aspects of cultural life, Armenian and

Semitic sources were important. Mirian and his

royal family, after being converted by St. Nino, a

Cappadocian woman, made Christianity the offi-

cial religion. Dates in the 320s and 330s are argued

for this event. The conversion of the west Geor-

gians land owes itself more directly to Greek Chris-

tianity.

The conversion of the Georgians was accom-

panied by the invention of an alphabet in the early

fifth century. Scripture, liturgy, and theological

works were translated into Georgian. This associ-

ation of the written language with the sacred is a

vital aspect of Georgian culture.

The Georgian capital was transferred from Mt-

skheta to Tiflis in the fifth century, a process be-

gun during the reign of King Vakhtang, called

Gorgasali, and completed under his son Dachi.

Vakhtang is portrayed in Georgian sources, in an

GEORGIA AND GEORGIANS

548

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

exaggerated fashion, as one of the important fig-

ures in transferring Kartli from an Iranian orien-

tation to a Byzantine one. This was a complex time

of struggle in the South Caucasus, not only be-

tween Byzantine and Persian Empires, but also

among various Armenian, Caucasian Albanian, and

Georgian states vying for power.

These currents of conflict were drastically al-

tered in the seventh century when Islam asserted

its military and political power. Tiflis was captured

by an Arab army in 645, a mere thirteen years af-

ter the death of Muhammad, and would remain

under Arab control until the time of David II/IV

(the numbering of the Bagratid rulers differs ac-

cording to one’s perspective) in the eleventh cen-

tury.

While Christianity was tolerated in Eastern

Georgia, the political center shifted westward, where

the Kingdom of Abkhazia grew to preeminence in

the eighth century. This realm was one of mixed

ethnic composition, including the Kartvelians of

West Georgia (i.e. the ancestors of today’s Min-

grelians and Svanetians) and, toward the north-

west, the ancestors of the Abkhazian people.

Meanwhile, a branch of the Bagratid family,

which had ruled parts of Armenia, and who were

clients of the Byzantine Empire, became prominent

in the Tao-Klarjeti region of southwest Georgia.

Because of Bagrat III (d. 1014), they became in-

heritors of the Kingdom of Abkhazia. From their

capital Kutaisi they contemplated the re-conquest

of Tiflis and the unification of Georgian lands. This

was accomplished in 1122 by David II/IV, called

the Builder, who reigned from 1089 to 1125. For

nearly two centuries, through the reign of Tamar

(1184–1212), the Georgians enjoyed a golden age,

GEORGIA AND GEORGIANS

549

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Georgian citizens wave flags and shout during an anti-government rally in Tiflis, May 26, 2001. © AFP/CORBIS

when they controlled a multiethnic territory from

the Black to the Caspian Seas and from the Cau-

casus Mountains in the north, toward the Ar-

menian plateau in the south. It was also a time of

great learning, with theological academies at

Gelati, near Kutaisi, and in the east at Iqalto on the

Kakhetian plain. The literary output of this time

reached it zenith with Shota Rustaveli’s epic tale

of heroism and chivalry, Knight in the Panther Skin,

written in the last quarter of twelfth century.

In the thirteenth century a succession of inva-

sions by Turks and Mongols brought chaos and

destruction upon the Georgians. These culminated

in the devastating raids of Timur in the early fif-

teenth century. From these depredations Georgian

society was very slow to recover, and for much of

the next four centuries it remained under the sway

of the Savafid Persian Empire and the Ottoman

Empire. Georgians at this time were active at the

Safavid court. The Bagratid dynasty continued to

reign locally over a collection of smaller states that

warred against one another. West European trav-

elers who ventured through Georgia in these cen-

turies give sad reports about the quality of life.

In the eighteenth century the Russian Empire’s

steady expansion brought it to the foothills of the

Caucasus Mountains and along the Caspian Sea to

the east of Georgia. Russians and Georgians had

been in contact through earlier exchanges of em-

bassies. Persian invasions in that century had been

especially harsh, and the Georgians looked to their

northern Orthodox neighbor for assistance. This

assistance culminated first in the 1783 Treaty of

Georgievsk, by which Irakle II’s realm of Kartli-

Kakheti became a protectorate of the Russian Em-

pire. Then, in 1801, soon after his accession to the

throne, Alexander I signed a manifesto proclaim-

ing Kartli-Kakheti to be fully incorporated into Rus-

GEORGIA AND GEORGIANS

550

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

C

A

U

C

A

S

U

S

M

O

U

N

T

A

I

N

S

L

E

S

S

E

R

C

A

U

C

A

S

U

S

M

T

S

.

Mt. Shkhara

16,627 ft.

5068 m.

Black

Sea

R

i

o

n

i

E

ng

u

ri

K

u

r

a

A

l

a

z

a

n

i

I

o

r

i

C

o

r

u

h

T

e

r

e

k

Sevdna

Lich

Tskhinvali

T’bilisi

Yerevan

Rustavi

Sokhumi

Batumi

K’ut’aisi

Gudauta

Tkvarcheli

Jvari

Senaki

Akhaltsikhe

Samtredia

Chiat’ura

Gori

Lagodekhi

Tsnori

Patara Shiraki

Poti

Zugdidi

Gagra

Ochamchira

Kobuleti

Bolnisi

Bogdanovka

Shaumyani

Ozurgeti

Khashuri

T’elavi

T’ianet’l

Vladikavkaz

Malhachlala

Nal’chik

Pyatigorsk

Armavir

Stavropol’

Nevinnomyssk

Borzhomi

Zestafoni

Ardahan

Kumayri

Kirovakan

Kirvovabad

Shäki

ABKHAZIA

AJARIA

SOUTH

OSSETIA

TURKEY

RUSSIA

ARMENIA

AZERBAIJAN

W

S

N

E

Georgia

GEORGIA

100 Miles

0

0

100 Kilometers

50

50

Georgia, 1992 © M

ARYLAND

C

ARTOGRAPHICS

. R

EPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

.

sia. Other parts of Georgia followed within the next

decade, although not always willingly.

Despite Russification efforts during the nine-

teenth century, the Georgian language and culture

underwent a renaissance that would undergird

Georgian national aspirations in the twentieth cen-

tury. The Society for the Spread of Literacy among

the Georgians, founded by Iakob Gogebashvili, was

important for fostering language acquisition, es-

pecially among children. Ilia Chavchavadze, Akaki

Tsereteli, and Vazha Pshavela dominated the liter-

ary scene into the twentieth century.

Georgians joined with comrades throughout

the Russian Empire in the revolutions of 1905 and

1917. When the Russian state began to shed its pe-

riphery in 1918, the Georgians briefly entered the

Transcaucasian Republic. This political entity lasted

from February until May 1918, but then split into

its constituent parts. Georgia proclaimed its inde-

pendence on May 26, 1918. The Democratic Re-

public of Georgia, beset by internal and external

enemies, lasted less than three years, and on Feb-

ruary 26, 1921, the Bolsheviks established Soviet

power in Tiflis. Independent Georgia had been gov-

erned mainly by Mensheviks, an offshoot of the

Russian Social Democratic Workers’ Party. They

were reluctant nationalists, led by Noe Zhordania,

who served as president. These Mensheviks became

the demonic foil for any number of aspects of Soviet

historiography and remained so for the Abkhazians

when they would press for greater autonomy.

The Soviet Socialist Republic of Georgia entered

the USSR through the Transcaucasian Soviet Fed-

erative Socialist Republic in 1922 and remained a

member of it until its dissolution in 1936. After-

ward the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic became

one of the USSR’s constituent republics. Three au-

tonomous regions were created within Georgia,

part of what some describe as a manifestation of

the “divide and conquer” regime of ethnic pseudo-

sovereignties. The South Ossetian Autonomous

Oblast was established across the border from

North Ossetia, and the Adjar A.S.S.R. was an en-

clave of historically Muslim Georgians in the

southwest. The third, and most troubled, part of

Georgia was Abkhazia. This region in the north-

west along the Black Sea coast had been in an am-

biguous federative, treaty status with Georgia, but

was finally, in 1931, incorporated as an A.S.S.R.

Georgia fared generally no better or worse for

having its “favorite son,” Iosep Jugashvili (a.k.a.

Josef Stalin), as the dictator of the Soviet Union.

With other parts of the U.S.S.R., it suffered the

depredations of party purges and the destruction

of its national intelligentsia in the 1930s.

In the latter decades of the Soviet period, Geor-

gia was held up as a sort of paradise within the

Soviet system. Agriculture, with tea and citrus in

the subtropical zone in the west, prospered, and the

Black Sea coast was a favorite spot for vacationers

from the cold north. The hospitality of the Geor-

gians, seemingly uncooled by Soviet power, and al-

ways warmed by the quality of Georgia’s famous

wines, wooed Soviet and foreign guests alike.

The Georgians developed a vigorous dissident

movement in the 1970s, with Zviad Gamsakhur-

dia and Merab Kostava playing leading roles. Tens

of thousands came out into the streets of Tiflis in

1978 to protest the exclusion of the Georgian lan-

guage from the new proposed Constitution of the

Georgian S.S.R.

As Gorbachev’s glasnost worked its effects, the

Georgian independence movement gave rise to com-

peting movements in South Ossetia and Abkhazia.

In reaction to a communiqué issued by Abkhazian

intellectuals in March 1989, the main streets of

Tiflis again overflowed with protesters. On the

morning of April 9, 1989, troops moved against

the demonstration, killing at least twenty and in-

juring scores of others. This outburst of violence

marked the beginning of the rapid devolution of

Soviet power in Georgia.

Georgia voted for its independence on April 9,

1991, and elected its first president, Zviad Gam-

sakhurdia, in May. His rule was harsh, and his

presidency barely survived the final collapse of the

USSR by a few months into 1992. Eduard She-

vardnadze, who had held power in Georgia under

Communist rule, and who became Gorbachev’s for-

eign minister, returned to Georgia, eventually to be

elected twice to the presidency. His presidency was

plagued by warfare and continuing conflict in

South Ossetia and Abkhazia, both of which claimed

independence. The ethnic conflict compounded the

economic dislocations, although the proposed

Baku-Tiflis-Ceyhan oil pipeline, the beginning of an

east-west energy corridor, has brought the promise

of some future prosperity.

See also: CAUCASUS; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET;

NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST; SHEVARDNADZE,

EDUARD AMVROSIEVICH

GEORGIA AND GEORGIANS

551

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, W. E. D. (1971). A History of the Georgian People:

From the Beginning down to the Russian Conquest in

the Nineteenth Century. New York: Barnes & Noble.

Aronson, Howard. (1990). Georgian: A Reading Grammar,

2nd ed. Columbus, OH: Slavica..

Braund, David. (1994). Georgia in Antiquity: A History of

Colchis and Transcaucasian Iberia, 550

BC

–

AD

562. Ox-

ford: Clarendon.

Lang, David Marshall. (1962). A Modern History of Soviet

Georgia. New York: Grove.

Rapp, Stephen H., Jr. (1997). “Imagining History at the

Crossroads: Persia, Byzantium, and the Architects of

the Written Georgian Past.” Ph.D. diss, University

of Michigan. Ann Arbor.

Suny, Ronald G. (1994). The Making of the Georgian Na-

tion, 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Toumanoff, Cyril. (1982). History of Christian Caucasia.

Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

P

AUL

C

REGO

GEORGIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

The Orthodox Church of Georgia, an autocephalous

church of the Byzantine rite Eastern Churches, is

an ancient community. It dates from the fourth

century, and stories of the evangelization of Kartli

center around St. Nino, called Equal to the Apos-

tles, who was born in Cappadocia, studied in

Jerusalem, and made her way through Armenia to

preach, heal, baptize, and convert the Georgian peo-

ple. Later traditions add apostolic visits from St.

Andrew and St. Simeon the Canaanite that reflect

evangelization of western Georgia. Christians in

Kartli continued to have a strong relationship with

the Armenians until the seventh century, when

these Christian people opted for different Chris-

tologies.

The autocephaly of the Orthodox Church is

claimed from the fifth century, when the Arch-

bishop of Mtskheta was given the title of Catholi-

cos. There was later also a Catholicos in western

Georgia, coinciding with the Kingdom of Abkhazia.

Western Georgia was evangelized more directly

by Greeks, and, after the split from the Armenians,

the entire Georgian Church strengthened its ties

with the church in Constantinople. Of the family

of Orthodox Churches that derive their liturgies

from the Byzantine tradition, the liturgical lan-

guage remains an archaic Georgian, not entirely in-

telligible to modern speakers.

The Georgians, for much of their history, have

lived under the rule of Muslim states. Arab Mus-

lims conquered Tiflis in 645, and it continued un-

der Muslim rule until 1122. After a brief golden

age the Georgians again came under Muslim con-

trol, alternating between Savifid Persians and Ot-

toman Turks. The church endured this period of

time with difficulty and looked for assistance from

their Orthodox neighbors in Russia toward the end

of the eighteenth century. The identification of the

Georgian nation with its Orthodox identity was

strengthened in this period, as the church was of-

ten the guarantor of linguistic and national iden-

tity and the legal authority for the nation.

Soon after the Russians annexed Georgia (1801),

the autocephaly of the Georgian Church was re-

scinded (1811) and it became a part of the Russian

Orthodox Church. The Georgian Church became

one of the institutions in Georgia through which

the imperial government attempted its program of

Russification.

The Georgian Church reclaimed its autocephaly

in 1918, as Georgia was proclaiming its indepen-

dence. This short period of breathing space was

quickly constricted with the imposition of Soviet

power, and nearly seven decades of atheist educa-

tion and oppression took a devastating toll on the

Georgian Church. As in the rest of the USSR, church

buildings were closed, confiscated for other pur-

poses, left to ruin, or destroyed. The role of the

clergy was restricted, and many came under sus-

picion as possible KGB agents.

The reign of Catholicos-Patriarch Ilia II from

December 1977 marked a new beginning in the life

of the Georgian Church. Slowly, Ilia began to re-

store episcopal sees and reopen churches. In Octo-

ber 1988, the Tiflis Theological Academy was

opened. With the changes of perestroika and glas-

nost and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Geor-

gian Church continued a dramatic revival. By the

end of the 1990s dozens of churches had been re-

built and many new ones built.

During the first decade of Georgia’s new inde-

pendence the church struggled to find its place in

society and in relation to the state. Georgian politi-

cians, especially the first president Zviad Gam-

sakhurdia, have used and misused their ties to the

church. The new Georgian Constitution not only

guarantees freedom of religion and conscience but

gives the church a place of historical honor. This

place of honor was given further definition and

practical meaning by a Concordat signed by the

government and the church on October 14, 2002.

GEORGIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

552

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY