Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

HAGIOGRAPHY

Various types of narratives with documentary and

commemorative functions for the Orthodox Church

are also regarded as important literary works in the

medieval Russian canon. Sacred biographies (vitae)

were written about persons who had followed

Christ’s example in life and shown evidence of pow-

ers after death to intercede for believers, attributes

that qualified them for sainthood. A short sum-

mary of the saint’s life was read initially at the cer-

emonial inauguration of the feast day and thereafter

to honor the saint’s memory. Longer vitae circu-

lated in religious anthologies of devotional readings.

Eulogistic biographies of rulers, initially written for

the funeral service, were recorded in chronicles, then

revised for hagiographical anthologies. Tales from

the Patericon record episodes from the lives of holy

monks, their teachings, or the history of a monas-

tic community. The vitae also include extended ac-

counts of miracles worked by icons, some of which

are viewed as local or national symbols, as well as

tales of individual miracles.

When the Kievans converted to Christianity

during the reign of Vladimir I (d. 1015), they re-

ceived Greek Orthodox protocols for the recogni-

tion and veneration of saints, as well as a corpus

of hagiographical texts. Beginning in the eleventh

century, Kievan monks produced their own records

of native saints. Veneration for the appanage

princes Boris and Gleb, murdered in the internecine

struggles following the death of their father

Vladimir, inspired three extended lives that are re-

garded as literary classics. Also influential was the

life of Theodosius (d. 1074), who became a monk

and helped to found the renowned Kiev Cave

Monastery. His biography, together with stories

of the monastery’s miraculous founding and of

its monks, was anthologized in the Kiev Cave

Monastery Patericon. The earliest hagiographical

works from the city-state of Novgorod, surviving

in thirteenth-century copies, focus on the bishops

and abbots of important cloisters. Lives of Suz-

dalian saints, such as the Rostov bishops Leontius,

Isaiah, and Ignatius, and the holy monk Abraham,

preserve collective memories of clerics who con-

verted the people of the area to Christianity.

In the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries,

Russian monks fled the cities, moving into wilder-

ness areas to live as hermits, then founded monas-

teries to house their disciples. The writings

produced in these monastery scriptoria promoted

H

623

asceticism as the highest model to which a Chris-

tian could aspire. Biographies of saints were sup-

plemented with long prefaces, prayers, laments,

and digressive praises employing the poetic

imagery and complex syntactic structures charac-

teristic of hymnography. An introductory com-

monplace, declaring the writer’s wish to write an

account that will be a fitting crown or garland of

praise for the saint, has inspired some scholars to

group these lives into a hagiographical school

whose trademark is “word-weaving” (pletenie sloves).

The most prominent writers of this school include

Metropolitan Cyprian (c. 1330–1406), identified by

some as a Bulgarian and others as a Serb, who

wrote a revised life of the holy Metropolitan Peter

in 1381; Epiphanius the Wise (second half of the

fourteenth century to the first quarter of the fif-

teenth century), author of the first life of St. Sergius

of Radonezh and St. Stephen of Perm (1390s);

and Pachomius the Logothete, an Athonian monk

sometimes identified as a Serb, who was commis-

sioned to rewrite the lives of widely venerated holy

men from Novgorod, Moscow, and leading monas-

teries between 1429 and 1484.

Sixteenth-century Muscovite hagiographers

composed expansive narratives celebrating saints

and icons viewed as protectors of the Russian tsar-

dom. The most influential promoter of the Mus-

covite school was Macarius. While serving as

archbishop of Novgorod (1537–1542), Macarius

ordered the collection of saints’ lives and icon leg-

ends, as well as other translated and original reli-

gious texts, for a twelve-volume anthology known

as the Great Menology (Velikie Minei Chetii). The first

“Sophia” version was donated to the Novgorod

Cathedral of Holy Wisdom in 1541. During his

tenure as metropolitan of Moscow (1542–1563),

Macarius commissioned additional lives of saints

who were recognized as national patrons at the

Church Councils of 1547 and 1549, for a second

expanded version of this anthology, which he do-

nated to the Kremlin Cathedral of the Dormition in

1552. A third fair copy was prepared between 1550

and 1554 for presentation to Tsar Ivan the Terri-

ble. Between 1556 and 1563, expanded sacred bi-

ographies of Kievan rulers Olga and Vladimir I,

appanage princes and princesses and four Moscow

metropolitans, as well as an ornate narrative about

the miracles of the nationally venerated icon Our

Lady of Vladimir, were composed for Macarius’s

Book of Degrees. These lives stressed the unity of the

Russian metropolitan see and the theme that the

line of Moscow princes had prospered because they

followed the guidance of the Church.

In the seventeenth century, two twelve-volume

hagiographical anthologies were produced by cler-

ics affiliated with the Trinity-Sergius Monastery:

the Trinity monk German Tulupov and the priest

Ioann Milyutin. Their still unpublished menologies

preserve lives of native Russian saints and legends

of local wonder-working icons not included in ear-

lier collections. In 1684 the Kiev Cave Monastery

monk Dmitry (Daniel Savvich Tuptalo), who

would be consecrated metropolitan of Rostov and

Yaroslavl in 1702, began to research Muscovite,

Western, and Greek hagiographical sources.

Dmitry’s goal was to retell the lives of saints and

legends of wonder-working icons in a form acces-

sible to a broad audience of Orthodox readers. The

first version of his reading menology was printed

in 1705 at the Kiev Cave Monastery. In 1759, a

corrected edition printed in Moscow became the au-

thorized collection of hagiography for the Russian

Orthodox Church. Also noteworthy as sources on

the spirituality of the seventeenth century are the

lives of Old Believer martyrs (Archpriest Avvakum,

burned as a heretic on April 1, 1682, and Lady

Theodosia Morozova who died in prison on No-

vember 2, 1675) and the life of the charitable lay-

woman Yulianya Osorina, written by her son

Kallistrat, district elder (gubnaya starosta) of

Murom between 1610 and 1640.

See also: KIEVAN CAVES PATERICON; ORTHODOXY; RUSS-

IAN ORTHODOX CHURCH; SAINTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bosley, Richard. (1997). “The Changing Profile of the

Liturgical Calendar in Muscovy’s Formative Years.”

In Culture and Identity in Muscovy: 1359–1584, eds.

A. M. Kleimola and G. D. Lenhoff. Moscow: ITZ-

Garant.

Ebbinghaus, Andreas. (1997). “Reception and Ideology in

the Literature of Muscovite Rus.” In Culture and Iden-

tity in Muscovy: 1359–1584, eds. A. M. Kleimola and

G. D. Lenhoff. Moscow: ITZ-Garant.

Fennell, John. (1995). A History of the Russian Church to

1448. New York: Longman.

Hollingsworth, Paul, tr. and ed. (1992). The Hagiography

of Kievan Rus’. Harvard Library of Early Ukrainian

Literature II. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Lenhoff, Gail D. (1997). Early Russian Hagiography: The

Lives of Prince Fedor the Black (Slavistiche Veröf-

fentlichungen 82). Berlin-Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz

Verlag.

Prestel, David K. (1992). “Biblical Typology in the Kievan

Caves Patericon.” The Modern Encyclopedia of Religions

HAGIOGRAPHY

624

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

in Russia and the Soviet Union 4:97-102. Gulf Breeze,

FL: Academic International Press.

G

AIL

L

ENHOFF

HAGUE PEACE CONFERENCES

Tsar Nicholas II summoned peace conferences at

The Hague in the Netherlands in 1899 and 1907.

His gestures appealed to pacifist sentiments in the

West, but his primary motives were quite prag-

matic. He hoped the 1899 conference would ban

the rapid-fire artillery being developed by Austria-

Hungary, Russia’s rival in the Balkans. Russia could

neither develop nor purchase such weapons except

at great expense. Finance Minister Serge Witte

urged that such money be spent instead on mod-

ernizing Russia’s economy. Having called the con-

ference, the Imperial government found itself tied

in knots. Its war minister warned that Russia

would need more and better arms to achieve its

goals in the Far East against Japan and in the Black

Sea region against Ottoman Turkey. Russia’s ma-

jor ally, France, objected to any limitations because

it sought new arms to cope with Germany. Before

the conference even opened, St. Petersburg assured

Paris that no disarmament measures would be

adopted.

The 1899 Hague Conference did not limit arms,

but it did refine the laws of war, including the

rights of neutrals. It also established an interna-

tional panel of arbiters available to hear cases put

before it by disputing nations.

A second Hague conference was planned five

years after the first, but did not convene then be-

cause Russia was fighting Japan. Nicholas did sum-

mon the meeting in 1907, after Russia began to

recover from its defeat by Japan and from its own

1905 revolution. It was during the 1905 upheaval

that Vladimir Ilich Lenin first articulated his view

on disarmament. The revolutionary task, he said,

is not to talk about disarmament (razoruzhenie) but

to disarm (obezoruzhit’) the ruling classes.

The Russian delegation in 1907 proposed less

sweeping limits on armaments than in 1899. How-

ever, when some governments proposed a five-year

ban on dirigibles, Russia called for a permanent ban.

Nothing came of these proposals, and the second

Hague conference managed only to add to refine-

ments to the laws of war.

See also: LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH; NICHOLAS II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Clemens, Walter C., Jr. “Nicholas II to SALT II: Change

and Continuity in East-West Diplomacy.” Interna-

tional Affairs 3 (July 1973):385-401.

Rosenne, Shabtai, comp. (2001). The Hague Peace Confer-

ences of 1899 and 1907 and International Arbitration:

Reports and Documents. The Hague: T.M.C. Asser.

Van den Dungen, Peter. (1983) The Making of Peace: Jean

de Bloch and the First Hague Peace Conference. Los An-

geles: Center for the Study of Armament and Dis-

armament, California State University.

W

ALTER

C. C

LEMENS

, J

R

.

HANSEATIC LEAGUE

The Hanseatic League was an association of north

European towns that dominated trade from Lon-

don in the west to Flanders, Scandinavia, Germanic

Baltic towns, and Novgorod in the east. There is no

precise date for the beginning of the Hansa, but

during the twelfth century German merchants es-

tablished a commercial center at Visby on the is-

land of Gotland, and by the early thirteenth century

founded Riga, Reval (Tallinn), Danzig (Gdansk), and

Dorpat (Tartu).

German and Scandinavian merchants estab-

lished the Gothic Yard (Gotsky dvor) and the Church

of St. Olaf on Novgorod’s Trading Side. Toward the

end of the twelfth century, Lübeck built the Ger-

man Yard (Nemestsky dvor, or Peterhof for the

Church of St. Peter) near the Gothic Yard. At the

same time Novgorodian merchants frequented

Visby, Sweden, Denmark, and Lübeck.

During the thirteenth century Lübeck gradu-

ally replaced Visby as the commercial center of the

League, and during the fourteenth century the

Gothic Yard became attached to Peterhof. In 1265

the north German towns accepted the “law of

Lübeck” and agreed for the common defense of the

towns. The League’s primary concern was to en-

sure open sea-lanes and the safety of its ships from

piracy. In addition to Novgorod, the League

founded counters or factories in Bruges, London,

and Bergen. At its height between the 1350s and

1370s, the League consisted of seventy or more

towns; perhaps thirty additional towns were

loosely associated with the Hansa. The cities met

irregularly in a diet (or Hansetage) but never de-

veloped a central political body or common navy.

The League could threaten to exclude recalcitrant

towns from its trade.

HANSEATIC LEAGUE

625

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

A Novgorod-Hansa agreement of 1269 laid the

basic structure of commercial relations. German

and Scandinavian merchants from Lübeck, Reval,

Riga, and Dorpat traveled twice per year, in sum-

mer and winter, to Novgorod. German merchants

were under their own jurisdiction within Peterhof,

but disputes involving Novgorodians fell to a joint

court that included the mayor and chiliarch (mili-

tary commander). During the thirteenth century

the German Yard elected its own aldermen, but dur-

ing the fourteenth century Lübeck and Visby chose

the aldermen. During the fifteenth century the

Livonian towns selected a permanent official who

resided in Novgorod.

Novgorod supplied the Hansa with furs, wax,

and honey, and received silver ingots (the source of

much of medieval Rus’s silver), as well as Flemish

cloth, salt, herring, other manufactured goods, and

occasionally grain. In 1369 the League imposed du-

ties on its silver exports to Novgorod; in 1373 it

halted silver exports for two years, and in 1388 for

four years. Novgorod turned to the Teutonic Or-

der for silver, but exports stopped after 1427. Dur-

ing the 1440s war broke out between Novgorod

and the Teutonic Order and the League, closing the

German Yard from 1443 to 1448.

Novgorod’s fur trade declined in the second half

of the fifteenth century. After conquering Novgorod

in 1478, Moscow closed the German Yard in 1494.

The Yard reopened in 1514, but Moscow developed

alternative trading routes through Ivangorod,

Pskov, Narva, Dorpat, and Smolensk. During the

sixteenth century Dutch and English traders further

undermined the League’s commercial monopolies.

In 1555 the English obtained duty-free privileges to

trade manufactured goods for Russian furs.

See also: FOREIGN TRADE; GERMANY, RELATIONS WITH;

NOVGOROD THE GREAT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dollinger, Philippe. (1970). The German Hansa, tr. D. S.

Ault. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

L

AWRENCE

N. L

ANGER

HARD BUDGET CONSTRAINTS

In market economies, firms face hard budget con-

straints. This means that they must cover their costs

of production using revenues generated either from

the sales of their product or from other financial

sources. In the short term, firms facing hard budget

constraints may borrow to cover their operating

costs. In the long term, however, if firms cannot

cover their costs from their revenues, they fail, which

means they must declare that the company is bank-

rupt or they must sell their assets to another firm.

Hard budget constraints coincide with a situation

where government authorities do not bail out or sub-

sidize poorly performing or loss-making firms.

Soviet industrial enterprises did not face hard

budget constraints. Unlike their counterparts in

market economies, Soviet firms’ primary objective

was to produce output, not to make a profit. In

many respects, planners controlled the financial

performance of firms, because planners set the

prices of labor, energy, and other material inputs

used by the firm and also set the prices on prod-

ucts sold by the firm. Centrally determined prices

in the Soviet economy did not facilitate an accurate

calculation of costs, because they were not based

on considerations of scarcity or efficient resource

utilization. Nor did prices reflect demand condi-

tions. Consequently, Soviet firms were not able to

accurately calculate their financial condition in

terms that would be appropriate in a market econ-

omy. More importantly, however, Soviet planners

rewarded the fulfillment of output targets with

large monetary bonuses and continually pressured

Soviet industrial enterprises to produce more. With

quantity targets given highest priority, managers

of Soviet firms were not concerned with costs, nor

were they faced with bankruptcy if they engaged

in ongoing loss-making activities. Without the

constraint to minimize or reduce costs, and given

the emphasis on fulfilling or expanding output tar-

gets, Soviet firms were encouraged to continually

demand additional resources in order to increase

their production. In contrast to hard budget con-

straints faced by profit-maximizing firms in mar-

ket economies, Soviet industrial enterprises faced

soft budget constraints.

See also: NEW ECONOMIC POLICY; VALUE SUBTRACTION;

VIRTUAL ECONOMY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kornai, Janos. (1986). Contradictions and Dilemmas: Stud-

ies on the Socialist Economy and Society, tr. Ilona

Lukacs, et al. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kornai, Janos. (1992). The Socialist System: The Political

Economy of Communism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press.

S

USAN

J. L

INZ

HARD BUDGET CONSTRAINTS

626

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

HAYEK, FRIEDRICH

(1899–1992), leading proponent of markets as an

evolutionary solution to complex social coordina-

tion problems.

One of the leaders of the Austrian school of eco-

nomics in the twentieth century, Friedrich Hayek re-

ceived the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Science

in 1974. Born to a distinguished family of Viennese

intellectuals, he attended the University of Vienna,

earning doctorates in law and economics in 1921

and 1923. He became a participant in Ludwig von

Mises’s private economics seminar and was greatly

influenced by von Mises’s treatise on socialism and

his argument about the impossibility of economic

rationality under socialism due to the absence of pri-

vate property and markets in the means of produc-

tion. Hayek developed a theory of credit-driven

business cycles, discussed in his books Prices and Pro-

duction (1931) and Monetary Theory and the Trade Cy-

cle (1933). As a result he was offered a lectureship,

and then the Tooke Chair in Economics and Statis-

tics at the London School of Economics and Politics

(LSE) in 1931. There he worked on developing an al-

ternative analysis to the nascent Keynesian economic

system, which he published in The Pure Theory of Cap-

ital in 1941, by which point the Keynesian macro

model had already become the accepted and domi-

nant paradigm of economic analysis.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Hayek made his ma-

jor contribution to the analysis of economic sys-

tems, pointing out the role of markets and the price

system in distilling, aggregating, and disseminat-

ing usable specific knowledge among participants

in the economy. The role of markets as an efficient

discovery procedure, generating a spontaneous

order in the flux of changing and unknowable spe-

cific circumstances and preferences, was empha-

sized in his “Economics and Knowledge” (1937),

“The Use of Knowledge in Society” (1945), and In-

dividualism and Economic Order (1948). These ar-

guments provided a fundamental critique of the

possibility of efficient economic planning and an

efficient socialist system, refining and redirecting

the earlier Austrian critique of von Mises. They

have also provided the basis for a substantial the-

oretical literature on the role of prices as a con-

veyor of information, and for the revival of

non-socialist economic thought in the final days of

the Soviet Union.

Hayek worked at LSE until 1950 when he

moved to Chicago, joining the Committee of Social

Thought at the University of Chicago. There Hayek

moved beyond economic to largely social and

philosophic-historical analysis. His major works in

these areas include his most famous defense of pri-

vate property and decentralized markets, The Road

to Serfdom (1944), New Studies in Philosophy, Poli-

tics and Economics (1978), and the compilation The

Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism (1988). These

works, more than his economic studies, provided

much of the intellectual inspiration and substance

behind the anti-Communist and economic liberal

movements in eastern Europe and the Soviet Union

in the 1980s and 1990s. In 1962 Hayek left Chicago

for the University of Freiburg in Germany, and

subsequently for Salzburg, where he spent the rest

of his life. The Nobel Prize in 1974 significantly

raised interest in his work and in Austrian eco-

nomics.

See also: LIBERALISM; SOCIALISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bergson, Abram. (1948). “Socialist Economics.” In A Sur-

vey of Contemporary Economics, ed. H. S. Ellis. Home-

wood, IL: Irwin.

Blaug, Mark. (1993). “Hayek Revisited.” Critical Review

7(1):51–60.

Caldwell, Bruce. (1997). “Hayek and Socialism.” Journal

of Economic Literature, 35(4):1856–1890.

Foss, Nicolai J. (1994). The Austrian School and Modern

Economics: A Reassessment. Copenhagen, Denmark:

Handelshojskolens Forlag.

Lavoie, Don. (1985). Rivalry and Central Planning: The So-

cialist Calculation Debate Reconsidered. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press.

Machlup, Fritz. (1976). “Hayek’s Contributions to Eco-

nomics.” In Buckley, William F., et al., Essays on

Hayek, ed. Fritz Machlup. Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale Col-

lege Press.

O’Driscoll, Gerald P. (1977). Economics as a Coordination

Problem: The Contribution of Friedrich A. Hayek. Kansas

City: Sheed, Andrews and McMeel.

R

ICHARD

E. E

RICSON

HEALTH CARE SERVICES, IMPERIAL

Prior to the reign of Peter the Great there were vir-

tually no modern physicians or medical programs

in Russia. The handful of foreign physicians em-

ployed by the Aptekarskyi prikaz (Apothecary bu-

HEALTH CARE SERVICES, IMPERIAL

627

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

reau) cared almost exclusively for the ruling fam-

ily and the court. Peter himself took a serious in-

terest in medicine, including techniques of surgery

and dentistry. His expansion of medical services and

medical practitioners focused on the armed forces,

but his reformist vision embodied an explicit con-

cern for the broader public health.

As of 1800 there were still only about five hun-

dred physicians in the empire, almost all of them

foreigners who had trained abroad. During the

eighteenth century schools in Russian hospitals

provided a growing number of Russians with lim-

ited training as surgeons or surgeons’ assistants.

The serious training of physicians in Russia itself

began in the 1790s at the medical faculty of

Moscow University and in medical-surgical acade-

mies in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Later these

were joined by medical faculties at universities in

St. Petersburg, Dorpat, Kazan, and elsewhere. The

early medical corps in Russia also included auxil-

iary medical personnel such as feldshers (physi-

cians’ assistants), midwives, barbers, bonesetters,

and vaccinators. Much of the population relied

upon traditional healers and midwives well into the

twentieth century.

Catherine the Great made highly visible efforts

to improve public health. In 1763 she created a

medical college to oversee medical affairs. She had

herself and her children inoculated against small-

pox in 1768 and sponsored broader vaccination

programs. She established foundling homes, an ob-

stetric institute in St. Petersburg, and several large

hospitals in the capitals. Her provincial reform

of 1775 created Boards of Public Welfare, which

built provincial hospitals, insane asylums, and

almshouses. In 1797, under Paul I, provincial med-

ical boards assumed control of medicine at the

provincial level, and municipal authorities took

over Catherine’s Boards of Public Welfare. With the

establishment of ministries in 1803, the Medical

College was folded into the Ministry of Internal Af-

fairs and its Medical Department.

The paucity of medical personnel made it dif-

ficult to provide modern medical care for a widely

dispersed peasantry that constituted over eighty

percent of the population. During the 1840s the

Ministry of State Domains and the Office of Crown

Properties initiated rural medical programs for the

state and crown peasants. The most impressive ad-

vances in rural medicine were accomplished by

zemstvos, or self-government institutions, during

the fifty years following their creation in 1864.

District and provincial zemstvos, working with the

physicians they employed, developed a model of

rural health-care delivery that was financed

through the zemstvo budget rather than through

payments for service. By 1914 zemstvos had

crafted an impressive network of rural clinics, hos-

pitals, sanitary initiatives, and schools for training

auxiliary medical personnel. The scope and quality

of zemstvo medicine varied widely, however, de-

pending upon the wealth and political will of indi-

vidual districts. The conferences that physicians

and zemstvo officials held at the district and

provincial level were a vital dimension of Russia’s

emerging public sphere, as was a lively medical

press and the activities of professional associations

such as the Pirogov Society of Russian Physicians.

By 1912 there were 22,772 physicians in the

empire, of whom 2,088 were women. They were

joined by 28,500 feldshers, 14,000 midwives,

4,113 dentists, and 13,357 pharmacists. The frag-

mentation of medical administration among a host

of institutions made it difficult to coordinate efforts

to combat cholera and other epidemic diseases.

Many tsarist officials and physicians saw the need

to create a national ministry of public health, and

a medical commission headed by Dr. Georgy Er-

molayevich Rein drafted plans for such a ministry.

Leading zemstvo physicians, who prized the zem-

stvo’s autonomy and were hostile to any expan-

sion of central government control, opposed the

creation of such a ministry. The revolutions of 1917

occurred before the Rein Commission’s plans could

be implemented.

See also: FELDSHER; HEALTH CARE SERVICES, SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, John T. (1980). Bubonic Plague in Early Mod-

ern Russia: Public Health and Urban Disaster. Balti-

more and London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Conroy, Mary Schaeffer. (1994). In Health and in Sick-

ness: Pharmacy, Pharmacists, and the Pharmaceutical

Industry in Late Imperial, Early Soviet Russia. Boul-

der, CO: East European Monographs.

Frieden, Nancy. (1981). Russian Physicians in an Era of

Reform and Revolution, 1856–1905. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Hutchinson John F. (1990). Politics and Public Health in

Revolutionary Russia, 1890–1918. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press.

McGrew, Roderick E. (1965). Russia and the Cholera,

1823–1832. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Ramer, Samuel C. (1982). “The Zemstvo and Public

Health.” In The Zemstvo in Russia: An Experiment in

HEALTH CARE SERVICES, IMPERIAL

628

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Local Self-Government, ed. Terence Emmons and

Wayne S. Vucinich. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Solomon, Susan, and Hutchinson, John F., eds. (1990).

Health and Society in Revolutionary Russia. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

S

AMUEL

C. R

AMER

HEALTH CARE SERVICES, SOVIET

Soviet socialized medicine consisted of a complex of

measures designed to provide free medical care to

the entire population, at the time of service, at the

expense of society. The Soviet Union was the first

country in the world to grant every citizen a con-

stitutional right to medical care. This commitment

was one of the few brighter (and redeeming) as-

pects of an otherwise bleak totalitarian system and

often held as an example to emulate by other na-

tions. The promise of universal, free (though not

necessarily equal) care was held as the fulfillment

of an age-long dream of providing care to those

who needed it regardless of their station in life and

ability to pay. It thus promised to eliminate the

commercial aspects of the medical encounter that,

in the eyes of many, had turned the physician into

a businessman concerned primarily with his in-

come and his willingness to treat only those who

were affluent.

In the first decade of the Soviet regime, the of-

ficial ideology held that illness and premature mor-

tality were the products of a faulty socioeconomic

system (i.e., capitalism) and that the establishment

of a socialist society (eventually to become com-

munist) would gradually eliminate most of the so-

cial causes of disease and early deaths by creating

improved conditions (better nutrition, decent stan-

dard of living, good working conditions, housing,

and prevention). This approach was set aside when

Stalin took power at the end of the 1920s. He

launched a program of forced draft industrializa-

tion and militarization at the expense of the stan-

dard of living, with an emphasis on medical and

clinical or remedial approach, rather than preven-

tion, to maintain and repair the working and fight-

ing capacity of the population. The number of

health personnel and hospital beds increased sub-

stantially, though their quality was relatively poor,

except for the elites.

Soviet socialized medicine was essentially a

public and state enterprise. It was the state that

provided the care. It was not an insurance system,

nor a mix of public and private activities, nor was

it a charitable or religious enterprise. The state as-

sumed complete control of the financing of med-

ical care. Soviet socialized medicine became highly

centralized and bureaucratized, with the Health

Ministry USSR standing at the apex of the medical

pyramid. Physicians and other health personnel be-

came state salaried employees. The state also fi-

nanced and managed medical education, all health

facilities from clinics to hospitals to rest homes,

medical research, the production of pharmaceuti-

cals, and medical technology. The system thus de-

pended entirely on budgetary allocations as line

items in the budget. More often than not, the health

care system suffered from low priority and was fi-

nanced on what came to be known as the residual

principle. After all other needs had been met, what-

ever was left would go to health care. Most physi-

cians (the majority of whom were women) were

poorly paid compared to other occupations, and

many medical facilities were short of funds to pur-

chase equipment and supplies or to maintain them.

Access to care was stratified according to oc-

cupation, rank, and location. Nevertheless the pop-

ulation, by and large, looked upon the principle of

socialized medicine as one of the more positive

achievements of the Soviet regime and welfare sys-

tem, and held to the belief that everyone was enti-

tled to free care. Their major complaint was with

the implementation of that principle. Soviet social-

ized medicine could be characterized as having a

noble purpose, but with inadequate resources,

flawed execution, and ending in mixed results.

See also: FELDSHER; HEALTHCARE SERVICES, IMPERIAL

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Field, Mark G. (1957). Doctor and Patient in Soviet Rus-

sia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Field, Mark G. (1967). Soviet Socialized Medicine: An In-

troduction. New York: The Free Press.

Field, Mark G., and Twigg, Judyth L., eds. (2000). Rus-

sia’s Torn Safety Nets: Health and Social Welfare Dur-

ing the Transition. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Ryan, Michael. (1981). Doctors and the State in the Soviet

Union. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Sigerist, Henry E. (1947). Medicine and Health in the So-

viet Union. New York: Citadel Press.

Solomon, Susan Gross, and Hutchinson, John F., eds.

(1990). Health and Society in Revolutionary Russia.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

M

ARK

G. F

IELD

HEALTH CARE SERVICES, SOVIET

629

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

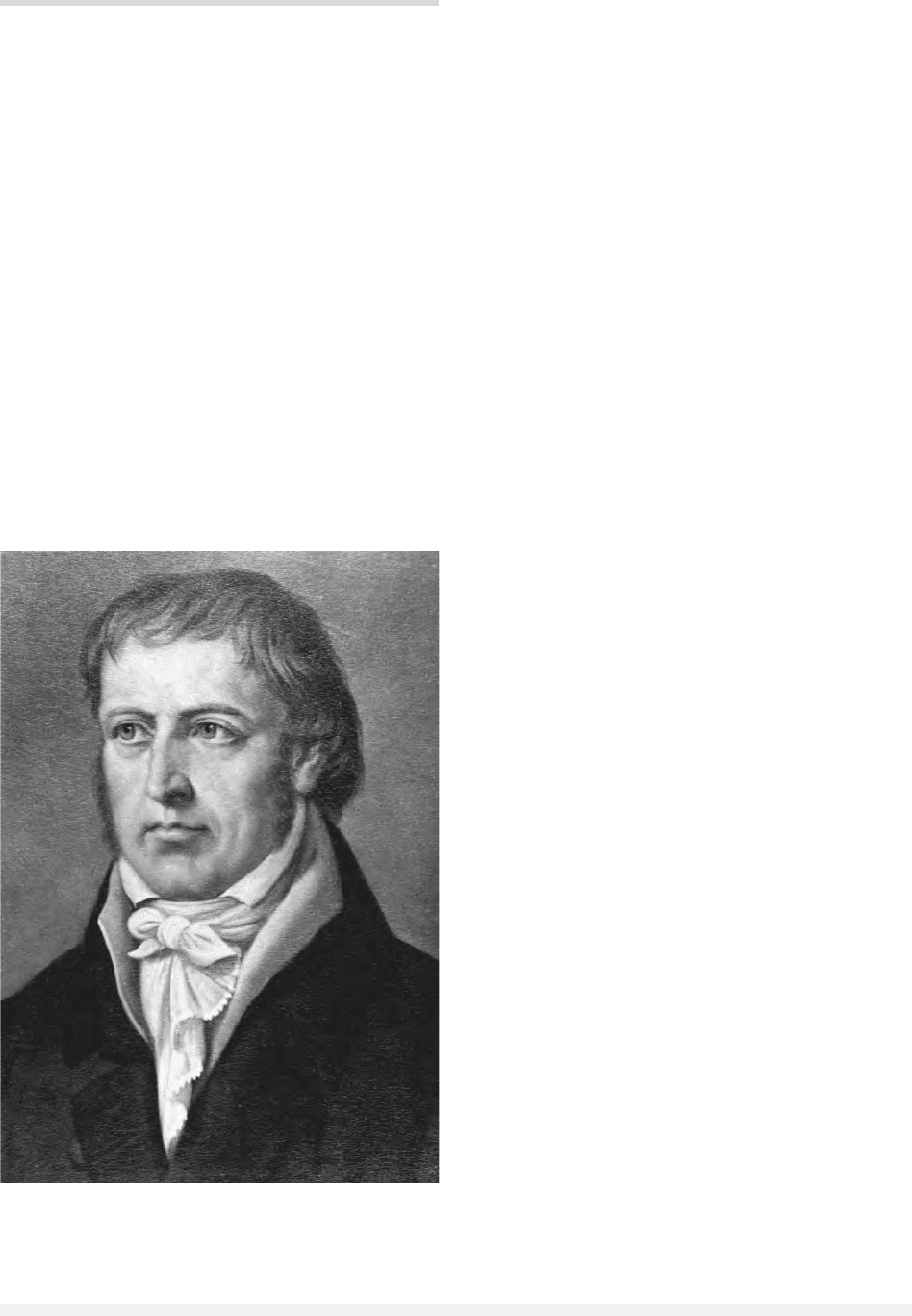

HEGEL, GEORG WILHELM FRIEDRICH

(1770–1831), leading nineteenth-century philoso-

pher.

Georg Wilhem Friedrich Hegel was one of the

most influential idealist philosophers of the nine-

teenth century. In German philosophical thought,

Hegel was rivaled in his own times perhaps only

by Immanuel Kant.

Hegel developed a sweeping spectrum of thought

embracing metaphysics, epistemology, logic, histo-

riography, science, art, politics, and society. One

branch of his philosophy after his death was re-

worked and fashioned into an “algebra of revolu-

tion,” as developed by Karl Marx and Friedrich

Engels, Russian Marxists and socialists, and later by

Vladimir I. Lenin, the founder of Bolshevism.

For Hegel, reality, which progresses dynamically

through a process, or phases, of thesis, antithesis,

and synthesis—his triadic concept of logic, inspired

by the philosophy of Heraclitus—is essentially spir-

itual. Ultimate, determinant reality, according to

Hegel, is the absolute World Spirit (Weltgeist). This

spirit acts in triadic, dialectical fashion universally

throughout world history. For Hegel, the state was

the principal embodiment, or bearer, of this process.

Because of its occasional obscurity and com-

plexity, Hegelianism as a social and political phi-

losophy soon split into various, contrasting

branches. The primary ones were the extremes

widely known as Right and Left Hegelianism. There

was also a middle, or moderate, form of Hegelian-

ism that in some ways influenced English, Italian,

American, and other branches of late-nineteenth-

century idealism and pragmatism.

Right (or Old) Hegelianism regarded reality more

or less passively, as indubitably rational. Whatever

is real is rational, as seen in the status quo. Spirit,

it alleged, develops on a grand, world scale via the

inexorable, dialectical processes of history. Wher-

ever this process leads must be logical since spirit

is absolute and triadically law-bound. In the mi-

lieu of contrasting European politics of the nine-

teenth century, Right Hegelianism translated into

reactionary endorsement of restorationism (restor-

ing the old order following the French Revolution

and the Napoleonic Wars) or support for monar-

chist legitimacy.

By contrast, however, Left (or Young) Hegelian-

ism, which influenced a number of thinkers, in-

cluding Marx and Engels together with Russian

Marxists and socialists, stressed the idea of grasp-

ing and understanding, even wielding, this law-

bound process. It sought thereby to manipulate

reality, above all, via society, politics, and the state.

For revolutionaries, the revolutionary movement

became such a handle, or weapon.

Hegel had taught that there was an ultimate

reality and that it was spiritual. However, when

the young, materialist-minded Marx, under the in-

fluence of such philosophers as Feuerbach, absorbed

Hegel, he “turned Hegel upside down,” to use his

collaborator Friedrich Engels’s apt phrase. While re-

taining Hegelian logic and the historical process of

the triadic dialectic, Marx, later Engels, and still

later Lenin, saw the process in purely nonspiritual,

materialistic, historical, and socioeconomic terms.

This became the ideology, or science, of historical

materialism and dialectical materialism as em-

braced by the Russian Marxist George Plekhanov

and, thence, by Lenin—but in an interpretation of

the ideology different from Plekhanov’s.

HEGEL, GEORG WILHELM FRIEDRICH

630

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel influenced the writings of Karl

Marx. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

In the Marx-Engels-Lenin-Stalin interpretation

of Left Hegelianism, historical change, the motor of

history as determined by the forces and processes

within the given social and economic system, is

law-bound and strictly predictable. As presented in

historical materialism, the history of societies de-

velops universally by stages—namely, from slavery,

to feudalism, to capitalism, and finally to social-

ism, whose final stage is full-fledged communism.

Each stage, except the merged last two (social-

ism/communism), contains the seeds of its own de-

struction (or “contradictions”) as the dialectical

process of socioeconomic development spirals up-

ward to the next historical stage. For instance, cap-

italism’s antithesis is seen in the seeds of its own

destruction together with the anticipation of the

new synthesis of socialism/communism. Such

seeds, said the Marxists, are capitalism’s impover-

ishment of a majority of the exploited population,

overproduction, unemployment, class struggle,

economic collapse, and, inevitably, revolution.

Progressive elements of the former, capitalist

order are then continued in new form in the final,

socialist/communist phase. This assumes the form

of industrialization, mass production, a just socio-

political order (under a workers’ dictatorship of the

proletariat). In this formulation the Marxists de-

veloped the theory of base and superstructure. The

base is the economic system; the superstructure are

such facets of society as government, laws, reli-

gion, literature, and the arts. The superstructure

both reflects and rationalizes the base.

Ultimately, under the dictatorship of the pro-

letariat, state power, as described in the Marxist

Critique of the Gotha Program, gradually withers

away. The society is thence led into the final epoch

of communism. In this final stage, a virtual mil-

lennium, there are no classes, no socioeconomic in-

equality, no oppression, no state, no law, no

division of labor, but instead pure equality, com-

munality, and universal happiness. Ironically, in

contrast to Marx’s formulation, the ultimate phase

in Hegel’s own interpretation of the dialectic in his-

tory was the Prussian state.

In Lenin’s construction of Marxism, Hegelian-

ism was given an extreme left interpretation. This

is seen, among other places, in Lenin’s “Philosoph-

ical Notebooks.” In this work Lenin gives his own

interpretation of Hegel. He indicates here and in

other writings that absolute knowledge of the in-

evitable historical process is attainable—at least by

those equipped to find it scientifically.

The leaders of the impending proletarian revo-

lution, Lenin says in his 1903 work, What Is to Be

Done?, become a select circle of intellectuals whose

philosophy (derived from Marx and Hegel) equips

them to assume exclusive Communist Party lead-

ership of the given country. Lenin could imagine

that such knowledge might allow a nation’s

(namely, Russia’s) socioeconomic development to

skip intermediate socioeconomic phases, or at least

shorten them. In this way, the Russian Bolsheviks

could lead the masses to the socialist/communist

stage of development all but directly. This could be

accomplished by reducing or suppressing the phase

of bourgeois capitalism. (This Leninist interepreta-

tion of the dialectic has been criticized by other

Marxists as running counter to Hegel’s, and Marx’s,

own explanations of the dialectic.)

Thus, in Lenin’s interpretation of Hegel and

Marx, the dictatorship of the proletariat becomes

the leader and teacher of society, the single indoc-

trinator whose absolute power (based on the peo-

ple) saves the masses from the abuses of the

contradictions of capitalist society, whether in rural

or urban society, while guiding society to the fi-

nal, communist phase.

See also: DIALECTICAL MATERIALISM; ENGELS, FRIEDRICH;

LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH; MARXISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gregor, A. James. (1995). “A Survey of Marxism.” In

The Oxford Companion to Philosophy, ed. Ted Hon-

derich. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hegel, Georg Wilhem Friedrich. (1967). The Philosophy of

Right. Oxford: Clarendon.

Marx, Karl, and Engels, Friedrich. (1962). Selected Works.

2 vols. Moscow: Foreign Languages Pub. House.

Possony, Stefan T. (1966). Lenin: The Compulsive Revolu-

tionary. London: Allen & Unwin.

Tucker, Robert C. (1972). Philosophy and Myth in Karl

Marx, 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univer-

sity Press.

Weeks, Albert L. (1968). The First Bolshevik: A Political

Biography of Peter Tkachev. New York: New York Uni-

versity Press.

A

LBERT

L. W

EEKS

HELSINKI ACCORDS

Signed at the Finnish capital of Helsinki on August

1, 1975, the Helsinki Accords were accepted by

HELSINKI ACCORDS

631

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

thirty-five participating nations at the first Con-

ference on Security and Cooperation in Europe. The

conference included all of the nations of Europe (ex-

cluding Albania), as well as the Soviet Union, the

United States, and Canada. The Helsinki Accords

had two noteworthy features. First, Article I for-

mally recognized the post-World War II borders of

Europe, which included an unwritten acknowl-

edgement of the Soviet Union’s control over the

Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania,

which the USSR had annexed in 1940. Second, Ar-

ticle VII stated that “the participating States recog-

nize the universal significance of human rights and

fundamental freedoms.” This passage, in theory,

held the Soviet Union responsible for the mainte-

nance and protection of basic human rights within

its borders.

Although the Soviet government was never se-

rious about conforming to the human rights pa-

rameters defined by the Helsinki Accords, the

national leadership under General Secretary Leonid

I. Brezhnev believed that its signing of the docu-

ment would improve the Soviet Union’s diplomatic

position with the United States and other Western

countries. Specifically, the state wished to foster the

perception that it was as an equal player in the pol-

icy of détente, in which both superpowers sought

to relax Cold War tensions. What the regime did

not anticipate, however, was that those outside the

Soviet Union, as well as many of the USSR’s own

citizens, would take the Accords seriously. Soon

after the Soviet delegation returned from Finland,

a number of human rights watchdog groups

emerged to monitor the USSR’s compliance with

the Accords.

Among those organizations that arose after the

signing of the accords was Helsinki Watch, founded

in 1978 by a collection of Soviet dissidents includ-

ing the notable physicist Andrei D. Sakharov and

other human rights activists living outside the

USSR. Helsinki Watch quickly became the best-

known and most outspoken critic of Soviet human

rights policies. This collection of activists and intel-

lectuals later merged with similar organizations to

form an association known as Human Rights

Watch. Many members of both Helsinki Watch and

Human Rights Watch who were Soviet citizens en-

dured state persecution, including trial, arrest, and

internal exile (e.g., Sakharov was exiled to the city

of Gorky) from 1977 to 1980. Until the emergence

of Mikhail S. Gorbachev as Soviet general secretary

in 1985, independent monitoring of Soviet compli-

ance with the accords from within the USSR re-

mained difficult, although the dissidents of Helsinki

Watch were never completely silenced. After the in-

troduction of openness (glasnost) and restructuring

(perestroika) under Gorbachev in the late 1980s,

however, these individuals’ efforts received much

acclaim at home and abroad. The efforts of Helsinki

Watch and its successor organizations served notice

in an era of strict social control that the Soviet

Union was accountable for its human rights oblig-

ations as specified by the Helsinki Accords.

See also: BREZHNEV, LEONID ILICH; DÉTENTE; DISSIDENT

MOVEMENT; HUMAN RIGHTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Civnet: A Website of Civitas International. (2003).

“The Helsinki Accords.” <http://www.civnet.org/

resources/document/historic/helsinki.htm>

Luxmoore, Jonathan. (1990). Helsinki Agreement: Dia-

logue or Discussion? New York: State Mutual Book

and Periodical Service.

Nogee, Joseph and Donaldson, Robert, eds. (1992) Soviet

Foreign Policy since World War II, 4th ed. New York:

Macmillan.

Sakharov, Andrei D. (1978). Alarm and Hope. New York:

Knopf.

C

HRISTOPHER

J. W

ARD

HERZEN, ALEXANDER IVANOVICH

(1812–1870), dissident political thinker and writer,

founder of Russian populism.

Alexander Ivanovich Herzen was born in

Moscow, the illegitimate son of a Russian aristocrat

and his German-born mistress. His family name,

derived from the German herz (“heart”), was given

to him by his father. In 1825 Herzen was deeply

affected by the Decembrist revolt that fueled his re-

jection of the Russian status quo. His early com-

mitments were developed in the companionship he

formed with a young relative, Nikolai Ogarev. In

1828 on the Vorobyevy Hills, they took a solemn

oath of personal and political loyalty to each other.

While a student at Moscow University, Herzen

became the center of gravity for a circle of criti-

cally-minded youth opposed to the existing social

and moral order; in 1834 both Herzen and Ogarev

were arrested for expressing their opinions in pri-

vate. Herzen was exiled to Perm and later to Vy-

atka, where he worked as a clerk in the governor’s

HERZEN, ALEXANDER IVANOVICH

632

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY