Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Neoplasm

sanely and simply in a troubled world.” They restored the

land and removed or rebuilt the buildings there. They farmed

organically and without machinery, feeding themselves from

their garden, and making and selling maple sugar. They

wrote about their experiences in The Maple Sugar Book (1950)

and Living the Good Life (1954). Their small farm became

a mecca for people seeking both to simplify their lives and

to live in harmony with

nature

, as well as each other.

In his 1972 autobiography, The Making of a Radical,

Nearing wrote that the attempt “to live simply and inexpen-

sively in an affluent society dedicated to extravagance and

waste” was the most difficult project he had ever undertaken,

but also the most physically and spiritually rewarding. He

defined the good life he was striving towards as life stripped

to its essentials—a life devoted to labor and learning, to

doing no harm to humans or animals, and to respecting the

land. As he wrote in his autobiography, he tried to live by

three basic principles: “To learn the truth, to teach the truth,

and to help build the truth into the life of the community.”

Confronted by the growth of the recreational industry

in Vermont during the 1950s, particularly the construction

of a ski resort near them, the Nearings sold their property

and moved their farm to Harborside, Maine, where Scott

Nearing died on August 24, 1983, just over two weeks after

his one-hundredth birthday.

Reviled as a radical for most of his life, Nearing’s

critique of the wastefulness of modern consumer society, his

emphasis on smallness, self-reliance, and the restoration of

ravaged land, as well as his

vegetarianism

, have struck a

responsive chord in many Americans since the late 1960s.

He is considered by some as the representative of twentieth

century American counterculture, and he has inspired activ-

ists throughout the environmental movement, from the edi-

tors of The Whole Earth Catalog and the founders of the first

Earth Day

to proponents of appropriate technology. He was

made an honorary professor emeritus of economics at the

Wharton School in 1973.

[Terence Ball]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Nearing, S. The Making of a Radical: A Political Autobiography. New York:

Harper and Row, 1972.

———, and H. Nearing. Living the Good Life: How to Live Sanely and

Simply in a Troubled World. Reissued with an introduction by Paul Good-

man. New York: Schocken Books, 1970.

———, and H. Nearing. The Maple Sugar Book. New York: Schocken

Books, 1971.

967

Nekton

Nekton are aquatic animals that swim or move freely in the

water. Their movement is generally not controlled by waves

and currents. Nekton include fish, squid, marine mammals,

and marine reptiles. They live in the sea, lakes, rivers, ponds,

and other bodies of water.

Fish are a major segment of the nektonic animals,

with approximately 14,500 kinds of fish living in the ocean.

Many nekton live near the ocean surface because food is

abundant there. Other nekton live in the deep ocean.

Most nekton are chordates, animals with bones or

cartilage. This category of nekton includes

whales

,

sharks

,

bony fish, turtles, snakes, eels,

dolphins

, porpoises, and

seals

.

Molluscan nekton like squid and octopus are inverte-

brates, animals with no bones. Squid, octopus, clams, and

oysters are mollusks. However, molluscan nekton have no

outer shells.

Molluscan nekton like squid and octopus are inverte-

brates, animals with no bones. Squid, octopus, clams, and

oysters are mollusks. However, molluscan nekton have no

outer shells.

Arthopod nekton are invertebrates like shrimp. Many

arthropod live on the ocean floor.

Most nektonic mammals live only in water. However,

walruses, seals, and sea otters can exist on land for a time.

Other nekton mammals include

manatees

and dugongs,

whale-like animals that live in the Indian Ocean.

[Liz Swain]

Nematicide

see

Pesticide

Neoplasm

Neoplasm results in the formation of both benign and, more

particularly, malignant tumors or cancers. A neoplasm is a

mass of new cells, which proliferate without control and

serve no useful function. This lack of control is particularly

marked in malignant tumors (

cancer

). The difference be-

tween a benign tumor and a malignant one is that the former

remains at its site of origin while the latter acquires the

ability to escape from its original location, migrate to another

place, and invade and colonize other tissues and organs. This

results in the death of the surrounding cells as the neoplasm

grows rapidly.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Neotropical migrants

Neotropical migrants

Birds that migrate each year between the American tropics

and higher latitudes, especially in North America, are known

as neotropical migrants. So called because they migrate from

the tropics of the “new world” (the Western hemisphere),

neotropical migrants are a topic of concern because many

species

have been declining in recent years, and because

they are vulnerable to

habitat

destruction and other hazards

in both winter and summer ranges. One survey of 62 forest-

dwelling migrant bird species found that 44 declined signifi-

cantly from 1978–1987. Migrants’ dependence on nesting

and feeding habitat in multiple regions, usually in different

countries, makes

conservation

difficult, since habitat pro-

tection often requires cooperation between multiple coun-

tries. In addition, it is often unclear whose fault it is when

populations fall. Most of the outcry over neotropical mi-

grants has been raised in the United States and Canada,

where summer bird populations have thinned noticeably in

recent decades. Conservationists in northern latitudes tend

to attribute bird disappearances to the destruction of tropical

forests and other winter habitat. In response, governments

in Mexico, Central America, and South America argue that

loss of suitable summer nesting habitat, as well as summer

feeding and shelter requirements, are responsible for the

decline of migratory birds.

About 250 species of birds breed in North America

and winter in the south. In the southern and western United

States 50-60% of breeding birds are migrants, a number that

rises to 80% in southern Canada and to 90% in the Canadian

sub-arctic. Among the familiar migrants are species of ori-

oles, hummingbirds, sandpipers and other wading birds, her-

ons and bitterns, flycatchers, swallows, and almost all war-

blers. Half of these winter in Mexico, the Bahamas, and the

Greater Antilles islands. Some 30 species winter as far south

as the western

Amazon Basin

and the foothills of the Andes

Mountains, where forest clearance poses a significant threat.

Species most vulnerable to habitat loss may be those that

require large areas of continuous habitat, especially the small

woodland birds, and aquatic birds whose wetland habitats

are being drained, filled, or contaminated in both summer

and winter ranges.

In addition to habitat loss, neotropical migrants suffer

from agricultural pesticides, which poison both food sources

and the birds themselves. The use of pesticides, including

such persistent

chemicals

as

dichlorodiphenyl-trichloro-

ethane

(DDT), has risen in Latin America during the same

period that

logging

has decimated forest habitat. Further-

more, some ecologists argue that migrants are especially

vulnerable in their winter habitat because winter ranges tend

to be geographically more restricted than summer ranges.

Sometimes an entire population winters in just a few islands,

968

swamps, or bays. Any habitat damage,

pesticide

use, or

predation could impact a large part of the population if the

birds concentrate in a small area.

Population declines are by no means limited to loss

of wintering grounds. An estimated 40% of North America’s

eastern deciduous forests, the primary breeding grounds of

many migrants, have either been cleared or fragmented.

Habitat fragmentation

is the term used to describe break-

ing up a patch of habitat into small, dispersed units, or

dissecting a patch of habitat with roads or suburban develop-

ments. This problem is especially severe on the outskirts of

urban areas, where suburbs continue to cut into the sur-

rounding countryside. For reasons not fully understood, neo-

tropical migrants appear to be more susceptible to habitat

fragmentation than short-distance migrants or species that

remain in residence year round. Hazards of fragmentation

include nesting failure due to predation (often by raccoons,

snakes, crows, or jays), nesting failure due to

competition

with human-adapted species such as starlings and English

sparrows, and

mortality

due to domestic house cats. (An

Australian study of house cat predation estimated that

500,000 cats in the state of Victoria had killed 13 million

small birds and mammals, including 67 different native bird

species.) In addition to hazards in their summer and winter

ranges, threats along

migration

routes can impact migratory

bird populations. Loss of stop-over

wetlands

, forests, and

grasslands

can reduce food sources and protective cover

along migration routes. Sometimes birds are even forced to

find alternative migration paths.

European-African migrants suffer similar fates and

risks to those of American migrants. In addition to wetland

drainage

, habitat fragmentation, and increased pesticide

use, Europeans and Africans also continue to hunt their

migratory birds, a hazard that probably impacts American

migrants but that is little documented here. It is estimated

that in Italy alone, some 50 million songbirds are killed each

year as epicurean delicacies.

Hunting

is also practiced in

Spain and France, as well as in African countries where

people truly may be short of food.

One of the principal sources of data on bird population

changes is the North American Breeding Bird Survey, an

annual survey conducted by volunteers who traverse a total

of 3,000 established transects each year and report the num-

ber of breeding birds observed. While this record is by no

means complete, it provides the best available approximation

of general trends. Not all birds are disappearing. Some have

even increased slightly, as a consequence of reduced exposure

to DDT, a pesticide outlawed in the United States because

it poisons birds, and because of habitat restoration efforts.

However the BBS has documented significant and troubling

declines in dozens of species.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Neurotoxin

Declines in migrant bird populations alarm many peo-

ple because birds are often seen as indicators of more general

ecosystem health

. Birds are highly visible and their disap-

pearance is noticeable, but they may indicate the simultane-

ous declines of insects, amphibians, fish, and other less visible

groups using the same habitat areas.

[Mary Ann Cunningham Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Terbogh, J. Where Have All the Birds Gone? Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press, 1989.

P

ERIODICALS

Friesen, L., P. F. Eagles, and R. J. Mackay. “Effects of Residential Develop-

ment on Forest-Dwelling Neotropical Migrant Songbirds,” Conservation

Biology 9, no. 6 (1995): 1408–l4.

Keast, A. “The Nearctic-Neotropical Bird Migration System.” Israel Journal

of Zoology 4, no. 1 (1995): 455–70.

“Neotropical Migratory Birds.” Conservation Biology 7, no. 3 (1993): 501–09.

Youth, H. “Flying Into Trouble” Worldwatch 7 (1994): 110–17.

Neritic zone

The portion of the marine

ecosystem

that overlies the

world’s continental shelves. This subdivision of the

pelagic

zone

includes some of the ocean’s most productive water.

This productivity supports a food chain culminating in an

abundance of commercially important fish and shellfish and

is largely a consequence of abundant sunlight and nutrients.

In the shallow water of the neritic zone, the entire water

column may receive sufficient sunlight for

photosynthesis

.

Nutrients are delivered to the area by terrestrial

runoff

and

through resuspension from the bottom by waves and cur-

rents. Runoff and dumping of waste also deliver pollutants

to the neritic zone, and this area is consequently among the

ocean’s most polluted.

Neurotoxin

Neurotoxins are a special class of metabolic poisons that

attack nerve cells. Disruption of the nervous system as a result

of exposure to neurotoxins is usually quick and destructive.

Neurotoxins are categorized according to the nature of their

impact on the nervous system. Anesthetics (ether, chloro-

form, halothane),

chlorinated hydrocarbons

(DDT, Diel-

drin, Aldrin), and

heavy metals

(

lead

,

mercury

) disrupt

the

ion

transport across cell membranes essential for nerve

action. Common pesticides, including carbamates such as

Sevin, Zeneb and Maneb and the organophosphates such

as Malathion and Parathion, inhibit acetylcholinesterase, an

969

enzyme

that regulates nerve signal transmission between

nerve cells and the organs and tissues they innervate.

Environmental exposure to neurotoxins can occur

through a variety of mechanisms. These include improper

use, improper storage or disposal, occupational use, and acci-

dental spills during distribution or application. Since the

identification and ramifications of all neurotoxins are not

fully known, there is risk of exposure associated with this

lack of knowledge.

Cell damage associated with the introduction of neuro-

toxins occurs through direct contact with the chemical or a

loss of oxygen to the cell. This results in damage to cellular

components, especially in those required for the synthesis

of protein and other cell components.

The symptoms associated with

pesticide poisoning

include eye and skin irritation, miosis, blurred vision, head-

ache, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, increased sweating, in-

creased salivation, diarrhea, abdominal pain, slight bradycar-

dia, ataxia, muscle weakness and twitching, and generalized

weakness of respiratory muscles. Symptoms associated with

poisoning of the central nervous system include giddiness,

anxiety, insomnia, drowsiness, difficulty concentrating, poor

recall, confusion, slurred speech, convulsions, coma with the

absence of reflexes, depression of respiratory and circulatory

centers, and fall in blood pressure.

The link between environmental neurotoxin exposure

and neuromuscular and brain dysfunction has recently been

identified. Physiological symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease,

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease),

and lathyrism have been identified in populations exposed

to substances containing known neurotoxins. For example

studies have shown that heroin addicts who used synthetic

heroin contaminated with methylphenyltetrahydropyridine

developed a condition which manifests symptoms identical

to those associated with Parkinson disease. On the island

of Guam, the natives who incorporate the seeds of the false

sago plant (Cycas circinalis) into their diet develop a condition

very similar to ALS. The development of this condition has

been associated with the specific nonprotein amino

acid

,B

methylamino-1-alanine, present in the seeds.

[Brian R. Barthel]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Aldrich, T., and J. Griffith. Environmental Epidemiology. New York: Van

Nostrand Reinhold, 1993.

P

ERIODICALS

Griffith, J., R.C. Duncan, and J. Konefal. “Pesticide Poisonings Reported

By Florida Citrus Field Workers.” Environmental Science and Health 6

(1985): 701–27.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Neutron

O

THER

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Annual Report 1989 and

1990. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Neutron

A subatomic particle with a mass of a proton and no electric

charge. It is found in the nuclei of all atoms except hydrogen-

1. A free neutron is unstable and decays to form a proton

and an electron with a half life of 22 minutes. Because they

have no electric charge, neutrons easily penetrate matter,

including human tissue. They constitute, therefore, a serious

health hazard. When a neutron strikes certain nuclei, such

as that of uranium-235, it fissions those nuclei, producing

additional neutrons in the process. The

chain reaction

thus

initiated is the basis for

nuclear weapons

and

nuclear

power

. See also Nuclear fission; Radioactivity

Nevada Test Site

The Nevada Test Site (NTS) is one of two locations (the

South Pacific being the other) at which the United States

has conducted the majority of its

nuclear weapons

tests.

The site was chosen for weapons testing in December 1950

by President Harry S. Truman and originally named the

Nevada Proving Ground. The first test of a nuclear weapon

was carried out at the site in January 1951 when a B-50

bomber dropped a bomb for the first of five tests in “Opera-

tion Ranger.”

The Nevada Test Site is located 65 miles (105 km)

northwest of Las Vegas. It occupies 1,350 square miles

(3,497 km

2

), an area slightly larger than the state of Rhode

Island. Nellis Air Force Base and the Tonopath Test Range

surround the site on three sides.

Over 3,500 people are employed by NTS, 1,500 of

whom work on the site itself. The site’s annual budget is

about $450 million, a large percentage goes for weapons

testing and a small percentage which is spent on the

radioac-

tive waste

storage facility at nearby

Yucca Mountain

.

The first nuclear tests at the site were conducted over

an area known as Frenchman Flat. Between 1951 and 1962,

a total of fourteen atmospheric tests were carried out in

this area to determine the effect of nuclear explosions on

structures and military targets. Ten underground tests were

also conducted at Frenchman Flat between 1965 and 1971.

Since 1971, most underground tests at the site have

been conducted in the area known as Yucca Flat. These tests

are usually carried out in

wells

10 ft (3 m) in diameter and

600 ft (182 m) to one mile (1.6 km) in depth. On an average,

about twelve tests per year are carried out at NTS.

970

Some individuals have long been concerned about pos-

sible environmental effects of the testing carried out a NTS.

During the period of atmospheric testing, those effects (

ra-

dioactive fallout

, for example) were relatively easy to ob-

serve. But the environmental consequences of underground

testing have been more difficult to determine.

One such consequence is the production of earth-

quakes, an event observed in 1968 when a test code-named

“Faultless” produced a fault with a vertical displacement of

15 ft (5 m). Such events are rare, however, and of less concern

than the release of radioactive materials into

groundwater

and the escape of radioactive gases through venting from

the test well.

In 1989, the Office of Technology Assessment (OTA)

of the United States Congress carried out a study of the

possible environmental effects from underground testing.

OTA concluded that the risks to humans from underground

testing at NTS are very low indeed. It found that, in the

first place, there is essentially no possibility that any release

of radioactive material could go undetected. OTA also calcu-

lated that the total mount of radiation a person would have

received by standing at the NTS boundary for every under-

ground test conducted at the site so far would be about equal

to 1/1000 of a single chest x-ray or equivalent to 32 minutes

more of exposure to natural

background radiation

in a

person’s lifetime. See also Groundwater pollution; Hazardous

waste; Nuclear fission; Radiation exposure; Radioactive de-

cay; Radioactivity

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

“New Bomb Factory to Open Soon at Test Site.” Bulletin of the Atomic

Scientists 46 (April 1990): 56.

“Press Releases Don’t Tell All.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 46 (January-

February 1990): 4–5.

Slonit, R. “In the State of Nevada.” Sierra (September-October 1991):

90–101.

O

THER

Office of Technology Assessment. The Containment of Underground Nuclear

Explosions. OTA-ISC-414. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing

Office, 1989.

New Madrid, Missouri

Those who think that earthquakes are strictly a California

phenomenon might be amazed to learn that the most power-

ful

earthquake

in recorded American history occurred in

the middle of the country near New Madrid (pronounced

MAD-rid), Missouri. Between December 16, 1811, and

February 7, 1812, about 2,000 tremors shook southeastern

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

New York Bight

Missouri and adjacent parts of Arkansas, Illinois, and Ten-

nessee. The largest of these earthquakes is thought to have

had a magnitude of 8.8 on the Richter scale, making it one

of the most massive ever recorded.

Witnesses reported shocks so violent that trees 6 feet

(2 meters) thick were snapped like matchsticks. More than

150,00 acres (60,000 ha) of forest were flattened. Fissures

several yards wide and many miles long split the earth.

Geysers of dry sand or muddy water spouted into the air.

A trough 150 miles (242 km) long, 40 miles (64 km) wide,

and up to 30 feet (9 m) deep formed along the fault line.

The town of New Madrid sank about 12 feet (4 m). The

Mississippi River reversed its course and flowed north rather

than south past New Madrid for several hours. Many people

feared that it was the end of the world.

One of the most bizarre effects of the tremors was

soil

liquefaction. Soil with high water content was converted

instantly to liquid mud. Buildings tipped over, hills slid into

the valleys, and animals sank as if caught in quicksand. Land

surrounding a hamlet called Little

Prairie

suddenly became

a soupy swamp. Residents had to wade for miles through

hip-deep mud to reach solid ground. The swamp was not

drained for nearly a century.

Some villages were flattened by the earthquake, while

others were flooded when the river filled in subsided areas.

The tremors rang bells in Washington, D.C., and shook

residents out of bed in Cincinnati, Ohio. Since the country

was sparsely populated in 1812, however, few people were

killed.

The situation is much different now, of course. The

damage from an earthquake of that magnitude would be

calamitous. Much of Memphis, Tennessee, only about 100

miles (160 km) from New Madrid, is built on

landfill

similar

to that in the Mission District of San Francisco where so

much damage occurred in the earthquake of 1990. St. Louis

had only 2,000 residents in 1812; nearly a half million live

there now. Scores of smaller cities and towns lie along the

fault line and transcontinental highways and pipelines cross

the area. Few residents have been aware of earthquake dan-

gers or how to protect themselves. Midwestern buildings

generally are not designed to survive tremors.

Anxiety about earthquakes in the Midwest was aroused

in 1990 when climatologist Iben Browning predicted a 50-

50 chance of an earthquake 7.0 or higher on or around

December 3, in or near New Madrid. Browning based his

prediction on calculations of planetary motion and gravita-

tional forces. Many geologists were quick to dismiss these

techniques, pointing out that seismic and geochemical analy-

ses predict earthquakes much more accurately than the meth-

ods he used. Although there were no large earth quakes

along the New Madrid fault in 1990, the

probability

of a

major tremor there remains high.

971

While the general time and place of some earthquakes

have been predicted with remarkable success, mystery and

uncertainty still abound concerning when and where “the

next big one” will occur. Will it be in California? Will it be in

the Midwest? Or will it be somewhere entirely unexpected?

Meanwhile, residents of New Madrid are planning emer-

gency exit routes and stocking up on camping gear and

survival supplies.

[William P. Cunningham Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Finkbeiner, A. “California’s Revenge: Someday a Major Earthquake Will

Ravage the United States–in the East.” Discover 11 (September 1990): 78–

82, 84–5.

Johnson, A. C., and L. R. Kanter. “Earthquakes in Stable Continental

Crust.” Scientific American 262 (March 1990): 68–75.

New Source Performance Standard

The Clean Air Acts of 1963 and 1967 gave to the

Environ-

mental Protection Agency

(EPA) the authority to establish

emission standards

for new and modified stationary

sources. These standards are called new source performance

standards (NSPS) and are determined by the best

emission

control technology available, the energy needed to use the

technology, and its overall cost. An example of an NSPS is

the standard set for plants that make Portland cement. Such

plants are allowed to release no more than 0.30 pounds of

emissions for each ton of raw materials used and to produce

an emission with no more than 20 percent opacity.

New York Bight

A bight is a coastal embayment usually formed by a curved

shoreline. The New York Bight forms part of the Middle

Atlantic Bight, which runs along the east coast of the United

States. The dimensions of the New York Bight are roughly

square, encompassing an area that extends out from the New

York-New Jersey shore to the eastern limit of Long Island

and down to the southern tip of New Jersey. The apex of

the bight, as it is known, is the northwestern corner, which

includes the

Hudson River

estuary, the Passaic and Hacken-

sack River estuaries, Newark Bay, Arthur Kill, Upper Bay,

Lower Bay, and Raritan Bay.

The New York Bight contains a valuable and diverse

ecosystem

. The waters of the bight vary from relatively

fresh near the shore to

brackish

and salty as one moves

eastward, and the range of

salinity

, along with the islands

and shore areas present within the area, have created a diver-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Niche

sity of environmental conditions and habitats, which include

marshes, woods, and beaches, as well as highly developed

urban areas. The portion of the bight near the shore lies

directly in the path of one of the major transcontinental

migratory pathways for birds, the North Atlantic

flyway

.

The New York Bight has a history of extremely inten-

sive use by humans, especially at the apex, and here environ-

mental impacts have been most severe. Beginning with the

settlement of New York City in the 1600s, the bight area

has supported one of the world’s busiest harbors and largest

cities. It receives more than two billion gallons per day of

domestic sewage and industrial

wastewater

. Millions of

gallons of

nonpoint source runoff

also pours into the bight

during storms, and regulated

ocean dumping

of dredge

spoils also occurs.

Numerous studies have shown that the sediments of

the bight, particularly at the apex, have been contaminated.

Levels of

heavy metals

such as

lead

,

cadmium

and

copper

in the sediments of the apex are of special concern because

they far exceed current guidelines on acceptable concentra-

tions. Similarly, organic pollutants such as

polychlorinated

biphenyls

(PCBs) from transformer oil and

polycyclic aro-

matic hydrocarbons

(PAHs) degraded from

petroleum

compounds are also in the sediments at levels high enough

to be of concern. Additionally, the sewage brings enormous

quantities of

nitrogen

and

phosphorus

into the bight which

promotes excessive growth of algae.

The continual polluting of the bight since the early

days of settlement has progressively reduced its capacity as

a food source for the surrounding communities. The oyster

and shellfishing industry that thrived in the early 1800s

began declining in the 1870s, and government advisories

currently prohibit shellfishing in the waters of the bight

due to the high concentrations of contaminants that have

accumulated in shellfish. Fishing is highly regulated

throughout the area, and health advisories have been issued

for consumption of fish caught in the bight. The bottom-

dwelling worms and insect larvae in the sediments of the

apex consist almost entirely of

species

that are extremely

tolerant of

pollution

; sensitive species are absent and

biodiv-

ersity

is low.

There are, however, some reasons to be optimistic.

The areas within the bight closest to the open ocean are

much cleaner than the highly degraded apex. In these less-

impacted areas, the bottom-dwelling communities have

higher species diversity and include species that prefer unim-

pacted conditions. Since the 1970s, enforcement of the

Clean Water Act

has helped greatly in reducing the quanti-

ties of untreated wastewater entering the bight. Some fish

species that had been almost eliminated from the area have

returned, and today striped bass again swim up the Hudson

River to spawn. See also Algal bloom; Environmental stress;

972

Marine pollution; Pollution control; Sewage treatment;

Storm runoff

[Usha Vedagiri]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Meyer, G. Ecological Stress and the New York Bight. Crownsville, MD:

Estuarine Research Federation, 1982.

New York-New Jersey Harbor Estuary Program. Toxics Characterization

Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1992.

P

ERIODICALS

Payton, B. M. “Ocean Dumping in the New York Bight.” Environment

27 (1985): 26.

NGO

see

Nongovernmental organization

Niche

The term niche is used in

ecology

with a variety of distinct

meanings. It may refer to a spatial unit or to a function unit.

One definition focuses on niche as a role claimed exclusively

by a

species

through

competition

. The word is also used

to refer to “utilization distribution” or the frequency with

which populations use resources. Still, niche is well enough

established in ecology that Stephen Jay Gould can label it

as “the fundamental concept” in the discipline, “an expression

of the location and function of a species in a habitat.” Niche

is used to address such questions as what determines the

species diversity of a

biological community

, how similar

organisms coexist in an area, how species divide up the

resources of an

environment

, and how species within a

community affect each other over time.

Niche has not been applied very satisfactorily in the

ecological study of humans. Anthropologists have used it

perhaps most successfully in the study of how small pre-

industrial tribal groups adapt to local conditions. Sociologists

have not been very successful with niche, subdividing the

human species by occupations or roles, creating false analo-

gies that do not come very close to the way niche is used

in biology. More recently, sociologists have extended niche

to help explain organizational behavior, though again dis-

torting it as an ecological concept.

Some attempts were made to build on the vernacular

sense of niche as in “he found his niche,” a measure of how

individual human beings attain multidimensional “fit” with

their surroundings. But this usage was again criticized as

too much of a distortion of the original meaning of niche

in biology. The word and related concepts remain common,

however, and are widely understood in vernacular usage to

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Nitrates and nitrites

describe how individual human beings make their way in

the world.

The niche concept has not been much employed by

environmental scientists, though it might be helpful in at-

tempts to understand the relationships between humans and

their environments, for instance. Efforts to formulate niche

or a synonym of some sort for use in the study of such

relationships will probably continue. The best use of niche

might be in its utility as an indicator of the richness and

diversity of

habitat

, serving in this way as an indicator of

the general health of the environment.

[Gerald L. Young Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Schoener, T. W. “The Ecological Niche.” In Ecological Concepts, edited by

J. M. Cherrett. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1989.

P

ERIODICALS

Broussard, C. A., and G. L. Young. “A Reorientation of Niche Theory in

Human Ecology: Toward a Better Explanation of the Complex Linkages

between Individual and Society.” Sociological Perspectives 29 (April 1986):

259–283.

Colinvaux, P. A. “Towards a Theory of History: Fitness, Niche, and Clutch

of Homo Sapiens.” Coevolution Quarterly 41 (Spring 1984): 94–107.

Mark, J., G. M. Chapman, and T. Gibson. “Bioeconomics and the Theory

of Niches.” Futures 17 (December 1985): 632–51.

Nickel

Nickel is a heavy metal, and it can be an important toxic

chemical in the

environment

. Natural

pollution

by nickel

is associated with soils that have a significant presence of a

mineral known as serpentine. Serpentine-laced soils are toxic

to nonadapted plants, and although the most significant

toxic stressor is a large concentration of nickel, sometimes

the presence of cobalt and/or chromium, along with high

pH

and an impoverished supply of nutrients also create a

toxic environment. Serpentine sites often have a specialized

flora

dominated by nickel-tolerant

species

, many of which

are endemic to such sites. Nickel pollution can occur through

human influence as well—most often in the vicinity of nickel

smelters or refineries. The best-known example of a nickel-

polluted environment occurs around the town of

Sudbury,

Ontario

, where smelting has been practiced for a century.

See also Heavy metals and heavy metal poisoning

Nickel mining

see

Sudbury, Ontario

973

NIMBY

see

Not In My Backyard

NIOSH

see

National Institute of Occupational

Safety and Health

Nitrates and nitrites

Nitrates and nitrites are families of chemical compounds

containing atoms of

nitrogen

and oxygen. Occurring natu-

rally, nitrates and nitrites are critical to the continuation of

life on the earth, since they are one of the main sources

from which plants obtain the element nitrogen. This element

is required for the production of amino acids which, in turn,

are used in the manufacture of proteins in both plants and

animals.

One of the great transformations of agriculture over

the past century has been the expanded use of synthetic

chemical fertilizers. Ammonium nitrate is one of the most

important of these fertilizers. In recent years, this compound

has ranked in the top fifteen among synthetic

chemicals

produced in the United States.

The increased use of nitrates as

fertilizer

has led to

some serious environmental problems. All nitrates are solu-

ble, so whatever amount is not taken up by plants in a field

is washed away into

groundwater

and, eventually, into

rivers, streams, ponds, and lakes. In these bodies of water,

the nitrates become sources of food for algae and other plant

life, resulting in the formation of algal blooms. Such blooms

are usually the first step in the eutrophication of a pond or

lake. As a result of eutrophication, a pond or lake slowly

evolves into a marsh or swamp, then into a bog, and finally

into a meadow.

Nitrates and nitrites present a second, quite different

kind of environmental issue. These compounds have long

been used in the preservation of red meats. They are attrac-

tive to industry not only because they protect meat from

spoiling, but also because they give meat the bright red color

that consumers expect.

The use of nitrates and nitrites in meats has been the

subject of controversy, however, for at least twenty years.

Some critics argue that the compounds are not really effective

as preservatives. They claim that preservation is really ef-

fected by the table salt that is usually used along with nitrates

and nitrites. Furthermore, some scientists believe that ni-

trates and nitrites may themselves be carcinogens or may be

converted in the body to a class of compounds known as the

nitrosamines, compounds that are known to be carcinogens.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Nitrification

In the 1970s, the

Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) responded to these concerns by dramatically cutting

back on the quantity of nitrates and nitrites that could be

added to foods. By 1981, however, a thorough study of the

issue by the

National Academy of Sciences

showed that

nitrates and nitrites are only a minor source of nitrosamine

compared to smoking, drinking water, cosmetics, and indus-

trial chemicals. Based on this study, the FDA finally decided

in January 1983 that nitrates and nitrites are safe to use in

foods. See also Agricultural revolution; Cancer; Cigarette

smoke; Denitrification; Drinking-water supply; Fertilizer

runoff; Nitrification; Nitrogen cycle; Nitrogen waste

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Canter, L. W. Nitrates in Ground Water. Chelsea, MI: Lewis, 1992.

Cassens, R. G. Nitrate-Cured Meat: A Food Safety Issue in Perspective.

Trumbull, CT: Food and Nutrition Press, 1990.

Selinger, B. Chemistry in the Marketplace. 4th ed. Sydney, Australia: Har-

court Brace Jovanovich, 1989.

P

ERIODICALS

“Clearest Lake Clouding Up.” Environment 30 (January-February 1988):

22–3.

Raloff, J. “New Acid Rain Threat Identified.” Science News 133 (30 April

1988): 276.

Nitrification

A biological process involving the conversion of nitrogen-

containing organic compounds into

nitrates and nitrites

.

It is accomplished by two groups of chemo-synthetic bacteria

that utilize the energy produced. The first step involves the

oxidation of ammonia to nitrite, and is accomplished by

Nitrosomas in the

soil

and Nitrosoccus in the marine

environ-

ment

. The second step involves the oxidation of

nitrites

into

nitrates

, releasing 18 kcal of energy. It is accomplished

by Nitrobacter in the soil and Nitrococcus in salt water. Nitrifi-

cation is an integral part of the

nitrogen cycle

, and is usually

considered a beneficial process, since it converts organic

nitrogen

compounds into nitrates which can be absorbed by

green plants. The reverse process of nitrification, occurring in

oxygen-deprived environments, is called

denitrification

and

is accomplished by other

species

of bacteria.

Nitrites

see

Nitrates and nitrites

974

Nitrogen

Comprising about 78% of the earth’s

atmosphere

, nitrogen

(N

2

) has an atomic number of seven and an atomic weight

of 14. It has a much lower solubility in water than in air—

there is approximately 200 times more nitrogen in the atmo-

sphere than in the ocean. The main source of gaseous nitro-

gen is volcanic eruptions; the major nitrogen sinks are syn-

thesis of nitrate in electrical storms and biological

nitrogen

fixation

. All organisms need nitrogen. It forms part of the

chlorophyll molecule in plants, it forms the nitrogen base

in DNA and RNA, and it is an essential part of all amino

acids, the building blocks of proteins. Nitrogen is needed

in large amounts for

respiration

, growth, and reproduction.

Nitrogen oxides

(NO

x

), produced mainly by motor vehicles

and internal

combustion

engines, are one of the main con-

tributors to

acid rain

. They react with water molecules in

the atmosphere to form nitric

acid

. See also Nitrates and

nitrites; Nitrogen cycle

Nitrogen cycle

Nitrogen

is a macronutrient essential to all living organisms.

It is an integral component of amino acids which are the

building blocks of proteins; it forms part of the nitrogenous

bases common to DNA and RNA; it helps make up ATP,

and it is a major component of the chlorophyll molecule in

plants. In essence, life as we know it cannot exist without

nitrogen.

Although nitrogen is readily abundant as a gas (it

comprises 79 percent of atmospheric gases by volume), most

organisms cannot use it in this state. It must be converted

to a chemically usable form such as ammonia (NH

3

)or

nitrate (NO

3

) for most plants, and amino acids for all ani-

mals. The processes involved in the conversion of nitrogen

to its various forms comprise the nitrogen cycle. Of all the

nutrient

cycles, this is considered the most complex and

least well understood scientifically. The processes that make

up the nitrogen cycle include

nitrogen fixation

, ammonifi-

cation,

nitrification

, and

denitrification

.

Nitrogen fixation refers to the conversion of atmo-

spheric nitrogen gas (N

2

) to ammonia (NH

3

) or nitrate

(NO

3

). The latter is formed when lightning or sometimes

cosmic radiation causes oxygen and nitrogen to react in the

atmosphere

. Farmers are usually delighted when electrical

storms move through their areas because it supplies “free”

nitrogen to their crops, thus saving money on

fertilizer

.

Ammonia is produced from N

2

by a special group of

mi-

crobes

in a process called biological fixation, which accounts

for about 90 percent of all fixed N

2

each year worldwide.

This process is accomplished by a relatively small number

of

species

of bacteria and blue-green algae, or blue-green

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Nitrogen cycle

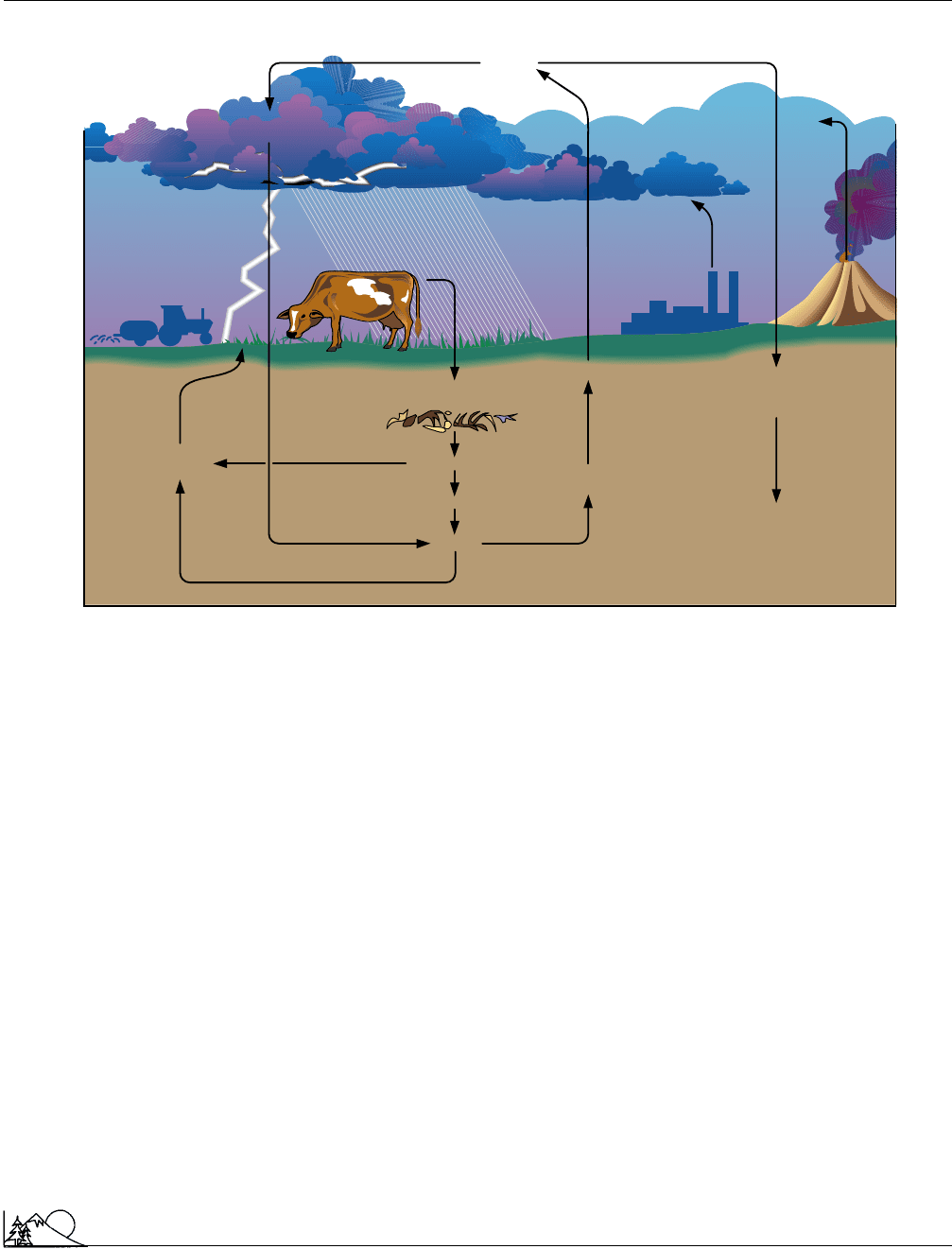

Spreading of

ammonia, ammonium

and nitrate fertilizers

Lightning

Protein

Atmospheric

fixation

Atmospheric

nitrogen

(N

2

)

Ammonia

(NH

3

)

Industrial

fixation

Uptake

by plants

Plant and animal

wastes, dead organisms

Nitrites

Nitrates

Denitrification

Nitrous

oxide

Nitrogen-fixing

bacteria in soil

and root nodules

Leaching of

ground water

Ammonia (NH

3

)

The nitrogen cycle. (Illustration by Hans & Cassidy.)

bacteria. The most well known of these nitrogen-fixing

organisms are the bacteria in the genus Rhizobium which

are associated with the root nodules of legumes. The legumes

attract these bacteria by secreting a chemical into the

soil

that stimulates the bacteria to multiply and enter the root

hair tips. The resultant swellings contain millions of bacteria

and are called root nodules, and here, near the soil’s surface,

they actively convert atmospheric N

2

to NH

3

, which is taken

up by the plant. This is an example of a symbiotic relation-

ship, where both organisms benefit. The bacteria benefit

from the physical location in which to grow, and they also

utilize sugars supplied by the plant photosynthate to reduce

the N

2

to NH

3

. The legumes, in turn, benefit from the NH

3

produced. The energetic cost for this nutrient is quite high,

however, and legumes typically take their nitrogen directly

from the soil rather than from their bacteria when the soil

is fertilized.

Although nitrogen fixation by legume bacteria is the

major source of biological fixation, other species of bacteria

are also involved in this process. Some are associated with

non-legume plants such as toyon (Ceanothus), silverberry

(Elaeagnus), water fern (Azolla), and alder (Alnus). With the

975

exception of the water fern, these plants are typically pioneer

species growing in low-nitrogen soil. Other nitrogen-fixing

bacteria live as free-living species in the soil. These include

microbes in the genera Azotobacter and Clostridium, which

live in

aerobic

and

anaerobic

sediments, respectively.

Blue-green algae are the other major group of living

organisms which fix atmospheric N

2

. They include approxi-

mately forty species in such genera as Aphanizomenon, Anab-

aena, Calothrix, Gloeotrichia, and Nostoc. They inhabit both

soil and freshwater and can tolerate adverse and even extreme

conditions. For example, some species grow in hot springs

where the water is 212°F (100°C), whereas other species

inhabit glaciers where the temperature is 32°F (0°C). The

characteristic bluish-green coloration is a telltale sign of their

presence. Some blue-green algae are found as pioneer species

invading barren soil devoid of nutrients, particularly nitro-

gen, either as solitary individuals or associated with other

organisms such as

lichens

. Flooded rice fields are another

prime location for nitrogen-fixing blue-green algae.

Perhaps the most common environments where blue-

green algae are found are lakes and ponds, particularly when

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Nitrogen cycle

the body of water is eutrophic—containing high concentra-

tions of nutrients, especially

phosphorus

. Algae can reach

bloom proportions during the warm summer months and

are often considered a nuisance because they float on the

surface, forming dense scum. The resultant odor following

decomposition

is usually pungent, and fish such as catfish

often acquire an off-flavor taste from ingesting these algae.

The next major component of the nitrogen cycle is

ammonification. It involves the breakdown of organic matter

(in this case amino acids) by decomposer organisms to NH

3

,

yielding energy. It is therefore the reverse reaction of amino

acid

synthesis. Dead plant and animal tissues and waste

materials are broken down to amino acids and eventually

NH

3

by the saprophagous bacteria and

fungi

in both soil

and water.

Nitrification is a biological process where NH

3

is oxi-

dized in two steps, first to NO

3

and next to nitrate (NO2).

It is accomplished by two genera of bacteria, Nitrosomonas

and Nitrobacter in the soil, and Nitrosococcus and Nitrococcus

in salt water. Since nitrification is an oxidation reaction, it

requires oxygenated environments.

Dentrification is the reverse reaction of nitrification

and occurs under anaerobic conditions. It involves the break-

down of

nitrates and nitrites

into gaseous N

2

by

microor-

ganisms

and fungi. Bacteria in the genus Pseudomonas (e.g.,

P. dentrificans) reduce NO

3

in the soil.

The cycling of nitrogen in an

ecosystem

is obviously

complex. In aquatic ecosystems, nitrogen can enter the food

chain through various sources, primarily surface

runoff

into

lakes or rivers, mixing of nutrient-rich bottom waters (nor-

mally only during spring and fall turnovers in north temper-

ate lakes), and biological fixation of atmospheric nitrogen

by blue-green algae.

Phytoplankton

(microscopic algae)

then rapidly take up the available nitrogen in the form of

NH

3

or NO

3

and assimilate it into their tissues, primarily

as amino acids. Some nitrogen is released by leakage through

cell membranes. Herbivorous

zooplankton

that ingest these

algae convert their amino acids into different amino acids

and excrete the rest. Carnivorous or omnivorous zooplankton

and fish that eat the herbivores do the same. Excretion

(usually as NH

3

and urea) is thus a valuable nutrient

recycl-

ing

mechanism in aquatic ecosystems. Different species of

phytoplankton actively compete for these nutrients when

they are limited. Decomposing bacteria in the lake, particu-

larly in the top layer of the bottom sediments, play an impor-

tant role in the breakdown of dead organic matter which

sinks to the bottom. The cycle is thus complete.

The cycling of nitrogen in marine ecosystems is similar

to that in lakes, except that nitrogen lost to the sediments

in the deep open water areas is essentially lost. Recycling

only occurs in the nearshore regions, usually through a pro-

cess called upwelling. Another difference is that marine phy-

976

toplankton prefer to take up nitrogen in the form of NH

3

rather than NO

3

.

In terrestrial ecosystems, NH

3

and NO

3

in the soil is

taken up by plants and assimilated into amino acids. As in

aquatic habitats, the nitrogen is passed through the

food

chain/web

from plants to herbivores to carnivores, which

manufacture new amino acids. Upon death,

decomposers

begin the breakdown process, converting the organic nitro-

gen to inorganic NH

3

. Bacteria are the main decomposers

of animal matter and fungi are the main group that break

down plants. Shelf and bracket fungi, for example, grow

rapidly on fallen trees in forests. The action of termites, bark

beetles, and other insects that inhabit these trees greatly

speed up the process of decomposition.

There are three major differences between nitrogen

cycling in aquatic versus terrestrial ecosystems. First, the

nitrogen reserves are usually much greater in terrestrial habi-

tats because nutrients contained in the soil remain accessible,

whereas nitrogen released in water and not taken up by

phytoplankton sinks to the bottom where it can be lost or

held for a long time. Secondly, nutrient recycling by herbi-

vores is normally a more significant process in aquatic ecosys-

tems. Thirdly, terrestrial plants prefer to take up nitrogen

as NO

3

and aquatic plants prefer NH

3

.

Forces in

nature

normally operate in a balance, and

gains are offset by losses. So it is with the nitrogen cycle in

freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems. Losses of nitrogen by

detritrification, runoff,

sedimentation

, and other releases

equal gains by fixation and other sources.

Humans, however, have an influence on the nitrogen

cycle that can greatly change normal pathways. Fertilizers

used in excess on residential lawns and agricultural fields

add tremendous amounts of nitrogen (typically as urea or

ammonium nitrate) to the target area. Some of the nitrogen

is taken up by the vegetation, but most washes away as

surface runoff, entering streams, ponds, lakes, and the ocean.

This contributes to the accelerated eutrophication of these

bodies of water. For example, periodic unexplained blooms

of toxic dinoflagellates off the coast of southern Norway

have been blamed on excess nutrients, particularly nitrogen,

added to the ocean by the fertilizer runoff from agricultural

fields in southern Sweden and northern Denmark. These

algae have caused massive dieoffs of

salmon

in the

maricul-

ture

pens popular along the coast, resulting in millions of

dollars of damage. Similar circumstances have contributed

to blooms of other species of dinoflagellates, creating what

are known as red tides. When filter-feeding shellfish ingest

these algae, they become toxic, both to other fishes and

humans. Paralytic shellfish

poisoning

may result within

thirty minutes, leading to impairment of normal nerve con-

duction, difficulty in breathing, and possible death. Saxo-